1. Introduction

The expression of directed motion has been one of the topics that has caught researchers’ attention for the past four decades. According to Talmy (Reference Talmy, Greenberg, Ferguson and Moravcsik1978), a motion event comprises four basic components: (i) Figure, i.e., an entity that moves, (ii) Motion of the Figure, (iii) Ground, i.e., a reference point with respect to which the Figure moves, and (iv) Path, i.e., the trajectory along which the motion takes place. In addition, a motion event may include a co-event, a semantic component that typically conveys information about the Manner or the Cause of motion. For example, the sentence John ran into the room explicitly mentions all these elements: the Figure (John), the Ground (room), the Path (into), and Motion conflated with the co-event (i.e., the Manner; ran).

Languages show systematic cross-linguistic variation in their encoding of directed motion events, particularly in the ways they map Path and Manner onto surface expressions. According to Talmy (Reference Talmy1991, Reference Talmy2000), speakers of satellite-framed languages (S-languages; e.g., English, German, Polish) typically use a conflated strategy, encoding Manner in the main verb and Path in a satellite around the main verb (e.g., particle, prefix) within a single clause (e.g., run into, jump up). In contrast, speakers of verb-framed languages (V-languages; e.g., Japanese, Spanish, Turkish) generally rely on a separated strategy, expressing Path in the main verb, and Manner in an additional subordinated clause (e.g., Sp. entrar corriendo ‘enter running’, salir saltando ‘exit jumping’); see also Malblanc (Reference Malblanc1968), Tesnière (Reference Tesnière1959), and Vinay and Darbelnet (Reference Vinay and Darbelnet1958) for previous discussions of motion event typology, especially with respect to French as compared to English and German. Because the encoding of Manner outside the main verb involves additional syntactic constituents that impose increased processing demands, speakers of V-languages frequently leave out Manner altogether from their descriptions of motion (Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan, Guo, Lieven, Ervin-Tripp, Budwig, Nakamura and Özçalışkan2009, Reference Özçalışkan2016; Özçalışkan & Slobin, Reference Özçalışkan, Slobin, Greenhill, Littlefield and Tano1999, Reference Özçalışkan, Slobin, Özsoy, Akar, Nakipoğlu-Demiralp, Erguvanlı-Taylan and Aksu-Koç2003; Slobin, Reference Slobin1991).

Most of the previous work on motion events focused on languages belonging to different types (e.g., V- vs. S-language) and provided compelling evidence for the aforementioned coding patterns: when talking about directed motion, speakers of S-languages predominantly used manner verbs, whereas speakers of V-languages largely relied on path verbs (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Özyürek, Kita, Brown, Furman, Ishizuka and Fujii2007; Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994; Gennari, Sloman, Malt, & Fitch, Reference Gennari, Sloman, Malt and Fitch2002; Hickmann, Taranne, & Bonnet, Reference Hickmann, Taranne and Bonnet2009; Naigles, Eisenberg, Kako, Highter, & McGraw, Reference Naigles, Eisenberg, Kako, Highter and McGraw1998; Strömqvist & Verhoeven, Reference Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004). Importantly, however, even though languages generally show preference for one type of lexicalization pattern over another, there is also evidence indicating that languages display significant intra-typological variation, i.e., variation within the same typological group, especially with respect to the degree to which they elaborate Path and Manner (see Goschler & Stefanowitsch, Reference Goschler and Stefanowitsch2013, for a recent collection of studies). For example, Ibarretxe-Antuñano (Reference Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004, Reference Ibarretxe-Antuñano and Guo2009) suggested that languages can be placed on a continuum of Path salience that cross-cuts the binary split between V- and S-languages. By way of illustration, although Spanish and Basque are both V-languages, speakers of Spanish tend to limit themselves to conveying Path in the verb, while speakers of Basque frequently add additional Path segments such as source and goal outside the verb, resulting in more elaborated Path descriptions (see also Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan, Guo, Lieven, Ervin-Tripp, Budwig, Nakamura and Özçalışkan2009, for a similar pattern in Turkish). Similarly, languages from the same typological affiliation can differ in their ability to express Manner. For instance, previous findings suggest that, when talking about self-motion, German speakers tend to encode more specific Manner dimensions in the main verb than Polish speakers, who generally make use of a smaller variety and amount of manner verbs (Lewandowski & Mateu, Reference Lewandowski and Mateu2016; Lewandowski & Özçalışkan, Reference Lewandowski and Özçalışkan2019). A similar pattern of differences has held true for other combinations of Slavic and Germanic languages such as, e.g., Polish vs. English (Kopecka, Reference Kopecka, Hasko and Perelmutter2010; Slobin, Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Kopecka, & Majid, Reference Slobin, Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Kopecka and Majid2014), Serbo-Croatian vs. English (Filipović, Reference Filipović2007), and Russian and Polish vs. English, Dutch, and Swedish (Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Divjak, & Rakhilina, Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Divjak, Rakhilina, Hasko and Perelmutter2010), with Germanic languages consistently showing a higher degree of Manner salience compared to Slavic languages; see also Ragnarsdóttir and Strömqvist (Reference Ragnarsdóttir, Strömqvist, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004) for an intra-genetic comparison of Manner encoding between Icelandic and Swedish, i.e., within the Germanic group.

Moreover, given that the affiliation to one or the other typological group is based on the most frequent encoding strategy, languages rarely if ever rely on their typical lexicalization pattern exclusively. For example, although English is predominantly an S-language, it has a number of path verbs, both Latinate (e.g., enter, exit, ascend, etc.) and of Germanic origin (e.g., rise, leave), which appear in V-framed type constructions (e.g., The plane ascended to 3000 feet; Stefanowitsch, Reference Stefanowitsch, Goschler and Stefanowitsch2013). In a similar vein, speakers of V-languages occasionally use the conflated strategy, especially if the motion event does not imply the crossing of a spatial boundary (e.g., Sp. correr hacia la puerta ‘run toward the door’, caminar hasta la colina ‘walk up to the hill’; Aske Reference Aske1989; Slobin & Hoiting, Reference Slobin and Hoiting1994).

In short, although languages can be classified as either S- or V-framed based on their most frequent lexicalization pattern, speakers of each language type also rely on packaging strategies that do not fully fit the characteristics of their typological affiliation. However, despite a growing body of research on patterns of motion expression, our understanding of the effects of variability within particular languages and language types is far from complete. For example, most of the previous studies predominantly investigated the expression of self-motion (i.e., motion instigated by the Figure itself, e.g., enter the room), while considerably less attention has been paid to the encoding of caused-motion (i.e., motion instigated by an external force, e.g., push the chair into the room), one notable exception to this general trend being the expression of placement events (e.g., Bowerman, Brown, Eisenbeiss, Narasimhan, & Slobin, Reference Bowerman, Brown, Eisenbeiss, Narasimhan, Slobin and Clark2002; Gullberg & Narasimhan, Reference Gullberg and Narasimhan2010; Kopecka & Narasimhan, Reference Kopecka and Narasimhan2012). In addition, the most common speech production tasks consisted of descriptions of motion scenes in which subjects were not faced with strict time limits while elicitation methods that involved the added pressure of time constraints were used rarely (but see Pourcel, Reference Pourcel2005, for an exception). To be more specific, in previous experiments, in which the elicitation stimuli were either pictures (e.g., Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994; Cadierno, Reference Cadierno, Han and Cadierno2010; Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan2015; Strömqvist & Verhoeven, Reference Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004) or video clips (e.g., Hendriks & Hickmann, Reference Hendriks and Hickmann2015; Lewandowski & Özçalışkan, Reference Lewandowski and Özçalışkan2019; Stam, Reference Stam2006), experimenters allowed the subjects to provide a motion event description in an unhurried manner after visualization. If the stimuli consisted of a series of isolated (decontextualized) scenes, participants were given time to describe each scene one at a time before proceeding to the next scene (e.g., Hendriks & Hickmann, Reference Hendriks and Hickmann2015; Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan2015). In turn, if the stimuli consisted of a series of connected events (i.e., a short story), the subjects were asked to perform a free prose recall task after visually inspecting the entire sequence of stimuli (e.g., Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994; Stam, Reference Stam2006).

In this study, we aim to further contribute to the ongoing debate on motion event encoding by integrating in a single research design for both (i) self- and caused-motion events and (ii) inter- and intra-typological comparisons, using simultaneous commentary of an ongoing video clip as our elicitation task. The decision to use a simultaneous ‘live commentary’ task instead of a recall task after visualization was based on the assumption that the added pressure of time constraints would minimize the effects of planned performance, thereby leading to more spontaneous speech production, typical of everyday communicative interactions (cf., e.g., Ochs, Reference Ochs and Givón1979; Roberts & Kirsner Reference Roberts and Kirsner2000). As such, our data collection methodology adds a qualitative aspect to previous speech production tasks, which in the majority of cases did not require participants to cope with the unpredictable demands of unplanned performance.

We focus on two S-languages, German and Polish, and one V-language, Spanish. German and Spanish are two representative examples of S- and V-languages, respectively (e.g., Bamberg, Reference Bamberg, Berman and Slobin1994; Cifuentes-Férez, Reference Cifuentes-Férez2008; Harr, Reference Harr2012; Sebastián & Slobin, Reference Sebastián, Slobin, Berman and Slobin1994; Talmy, Reference Talmy2000). Polish, in turn, despite its typological similarity to German, differs from prototypical S-languages in its lexicalization of Manner, with less specific encoding of this semantic component in the main verb (Kopecka, Reference Kopecka, Hasko and Perelmutter2010; Lewandowski & Mateu, Reference Lewandowski and Mateu2016). Hence, the combination of languages involved in our study constitutes a relevant proving ground for the effect of both inter- and intra-typological factors in the linguistic construal of motion.

Starting with inter-typological variation, following earlier work (e.g., Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994; Strömqvist & Verhoeven, Reference Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004; Talmy, Reference Talmy2000), we expect German and Polish speakers to display greater reliance on manner tokens (i.e., number of manner verbs) and types (i.e., variety of manner verbs) than Spanish speakers in their descriptions of self-motion. Although earlier work on inter-typological contrasts in the expression of caused-motion is relatively scarce compared to earlier work on self-motion, we expect the same pattern of variation to apply to caused-motion descriptions based on the available empirical evidence (Hendriks & Hickmann, Reference Hendriks and Hickmann2015; Hendriks, Hickmann, & Demagny, Reference Hendriks, Hickmann and Demagny2008; Ji, Hendriks, & Hickmann, Reference Ji, Hendriks and Hickmann2011).

Turning next to intra-typological variation, based on previous work by Kopecka (Reference Kopecka, Hasko and Perelmutter2010) and Lewandowski and Mateu (Reference Lewandowski and Mateu2016), we expect greater use of manner tokens and types in German compared to Polish in self-motion descriptions. We also explore the possibility that caused-motion events will show the same pattern of similarities and differences (i.e., greater reliance on manner tokens and types in German compared to Polish).

Turning last to intra-linguistic variation, we predict that speakers of all three languages will display greater reliance on manner tokens in their caused-motion descriptions as compared to their self-motion descriptions. This prediction is based on earlier studies on physical and metaphorical motion (e.g., Hendriks & Hickmann, Reference Hendriks and Hickmann2015; Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan2005), suggesting that speakers of both V- and S-languages increase the number of manner verbs (i.e., manner tokens) in describing events from a caused motion perspective. However, we cannot predict if the same pattern of intra-linguistic variation also applies to the variety of manner verbs (i.e., manner types), given the lack of systematic of evidence in earlier work on this subject.

2. Methods

2.1. sample

The participants included 15 adult German native speakers (Mage = 25, range = 19–33; 8 females), 15 adult Polish native speakers (Mage = 23, range = 20–24; 9 females), and 15 adult native Spanish native speakers (Mage = 21, range = 20–36; 10 females). Data were gathered at different universities in Germany, Poland, and Spain. Most of the participants were university students, and 4 participants were teaching assistants with postgraduate degrees. The sample size was based on earlier work by Özçalışkan (Reference Özçalışkan, Guo, Lieven, Ervin-Tripp, Budwig, Nakamura and Özçalışkan2009), which showed that 10 subjects per group would provide a minimum of 84% power to detect reliable effects at p < .05 (η2 = 0.08; n = 10/group).

2.2. data collection

Participants were interviewed individually in a laboratory room. They were asked to watch a silent 360-second-long extract from Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (cf. Pourcel, Reference Pourcel2005) and to provide a ‘live commentary’ of what was happening in the video to an experimenter. The elicitation stimulus depicted both self-motion events (6 different manners: step, rush, swim, jump, stagger, walk; 6 different paths: forward, backward, upward, downward, into, out) and caused-motion events (6 different Manners: push, pull, throw, submerge, drop, drag; 6 different Paths: forward, backward, upward, downward, into, out); see Appendix I for a sequence of events included in the stimulus video. Participants’ responses were videotaped.

2.3. data coding

Responses were transcribed by native speakers of the corresponding languages and divided into clauses. A clause unit was defined as a main verb and its associated arguments/adjuncts (e.g., Germ. Sie laufen die Treppe runter ‘They run down the stairs’; Pl. Schodzą po schodach ‘They walk down the stairs’; Sp. Entran corriendo en el agua ‘They enter the water running’). Each clause was classified as either self-motion (i.e., events involving self-instigated movement; e.g., Germ. Sie springen aus dem Wasser raus ‘They jump out of the water’; Pl. Wychodzą z rzeki ‘They walk out of the river’; Sp. Salen del agua ‘They exit the water’) or caused-motion (i.e., events involving other-instigated movement; e.g., Germ. Er wirft den Mann ins Wasser ‘He throws the man into the water’; Pl. Wrzuca kamień do rzeki ‘He throws the stone into the river’; Sp. Tira al hombre al agua ‘He throws the man into the water’). Each clause unit was further coded for verb type. Following earlier work (e.g., Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan2004), motion verbs were grouped as either manner verbs (e.g., Germ. klettern ‘climb’, Pl. biegać ‘run’, Sp. empujar ‘push’) or non-manner verbs (i.e., path verbs; e.g., Sp. entrar ‘enter’, Germ. kommen ‘come’, and neutral verbs; e.g., Sp. ir ‘go’, Pl. ruszać się ‘move’). The Manner category included descriptions in which Manner and Path were conveyed in a single clause (i.e., the conflated strategy; e.g., Germ. Er klettert hoch ‘He climbs up’; Pl. Wbiegł do rzeki ‘He ran into the river’; Sp. Empuja a Chaplin al agua ‘He pushes Chaplin into the water’), while the non-manner category included descriptions in which Manner was either not expressed or was expressed in a separate subordinate clause (i.e., the separate strategy; e.g., Germ. Er kommt ‘He comes’; Pl. Rusza się do tyłu ‘He moves backward’; Sp. Entra corriendo ‘He enters running’). Given our interest in directed motion events, manner-only clauses (e.g., Germ. Er springt ‘He jumps’; Pl. Biegnie ‘He runs’; Sp. Se tambalea ‘He wobbles’) were not coded. Reliability was assessed by three independent coders (one per language) who were blind to the hypotheses of our study. The first coder coded all responses, and the independent coders coded 20% of the data, which included 3 randomly selected participants in each language. Agreement between coders was 92%.

2.4. analysis

We analyzed between- and within-language differences in the use of motion verbs separately for tokens and types. To check predictions on the token level we fit a Bayesian mixed model with a binomial link function (logistic regression) as implemented in the R-package brms (Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2018), which provides an interface to the Stan programming language (https://mc-stan.org/). To be more specific, we modeled the probability of an uttered verb to be a manner verb. Our model includes two fixed effects, namely language with three levels, that is, German, Polish, and Spanish, and event type with two levels, that is, self-motion and caused-motion. As random variables, we implemented the speaker only. The uttered verb itself is either manner or non-manner and is not suitable as a random variable in this setting. We introduced a random slope of event type on the speaker. The specific predictions were checked on the basis of post-hoc tests computed by the emmeans R package (Length, Reference Length2019).

The predictions regarding the number of types could not be addressed in this standard framework given that their distribution does not easily fit into any of the standard distributions from the exponential family. Therefore, we decided to use the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Since the type-based predictions are very simple and persist only to very specific subsets of the data, this can be done with little disadvantage. The data along with the statistical analyses can be found online at <https://osf.io/gp46y/?view_only=bac22d906e9f460f81bfc0e6b70974e7>.

3. Results

3.1. tokens

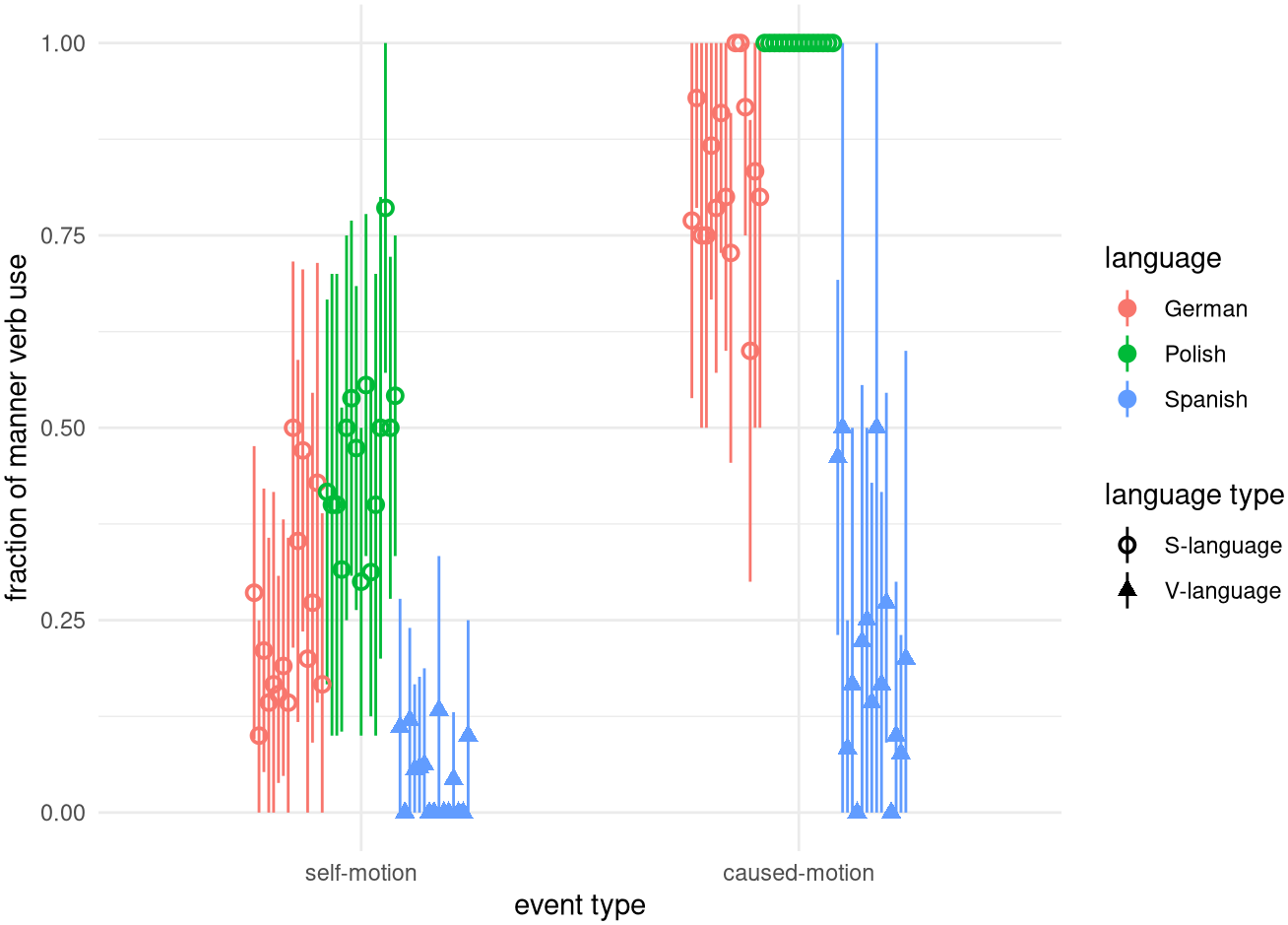

Starting with verb tokens, we first looked at inter-typological variation and found the expected differences in the encoding of motion events. Specifically, German and Polish speakers showed greater reliance on manner tokens than Spanish speakers when talking about both self- and caused-motion, resulting in more conflated descriptions in German and Polish compared to Spanish. When contrasting Spanish speakers against German and Polish speakers for self-motion, we observe a point estimate of 0.091, meaning that the odds for the utterance of a manner verb for describing self-motion events in Spanish is approximately an eleventh of that in Polish and German. The credibility interval reaches from 0.04 up to 0.15, which is well below one, corroborating our predictions; see Figure 1 for a summary of our results for manner tokens. In a similar vein, when contrasting Spanish speakers against German and Polish speakers for caused-motion, we observe a point estimate of 0.0004, with the credibility interval reaching from 1.7x10-9 up to 0.0072, a result that is also in line with our predictions.

Fig. 1. Fraction of manner verbs used by German, Polish, and Spanish speakers in self- and caused-motion descriptions.

Note. Each circle/triangle represents the fraction of manner verbs used by a specific speaker, color coded for the language, while the shape of the symbols represents the language type. Error bars are bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Next turning to intra-typological variation, contrary to our predictions, German speakers did not show greater reliance on manner tokens than Polish speakers in their descriptions of self- or caused-motion events. Instead, the opposite pattern became evident: regardless of event type, Polish speakers showed a higher proportion of manner tokens than German speakers, resulting in greater reliance on the conflated pattern in Polish as compared to German. For self-motion, the confidence interval reaches from 0.22 up to 0.56, centered around an odds ratio of 0.38. For caused-motion, the confidence interval reaches from 2.3x10-15 up to 0.02, centered around an odds ratio of 8.06x10-5.

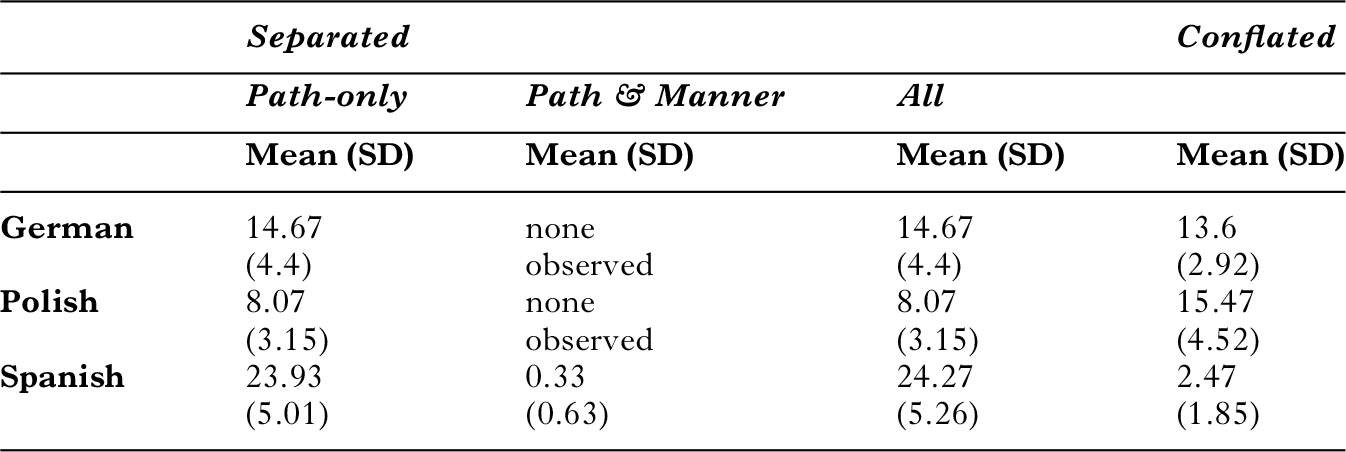

Turning last to intra-linguistic variation, in line with our hypothesis we found that event type (i.e., self-motion, caused-motion) had an effect on the packaging of motion elements. Specifically, German, Polish, and Spanish speakers increased their use of manner tokens when talking about caused-motion, resulting in more conflated caused-motion descriptions compared to self-motion descriptions. If we look at the overall effect of the variable event type we get a clear result for the odds ratio between self-motion and caused-motion with a credibility interval from 1.6×10−6 up to 0.037, centered around an odds ratio of 0.0056. Since this ignores clearly visible interactions it is not a well interpretable result. If we make separate tests for our three languages, we get an estimate of 0.06 for German, 1.3×10−5 for Polish, and 0.2 for Spanish. This result still fully vindicates our predictions. Examples of self- and caused-motion descriptions produced by German, Polish, and Spanish speakers are provided in Tables 2–4 in Appendix II, while Table 6 in Appendix IV summarizes the mean frequencies of clauses with separated and conflated packaging of motion in each language.

3.2. types

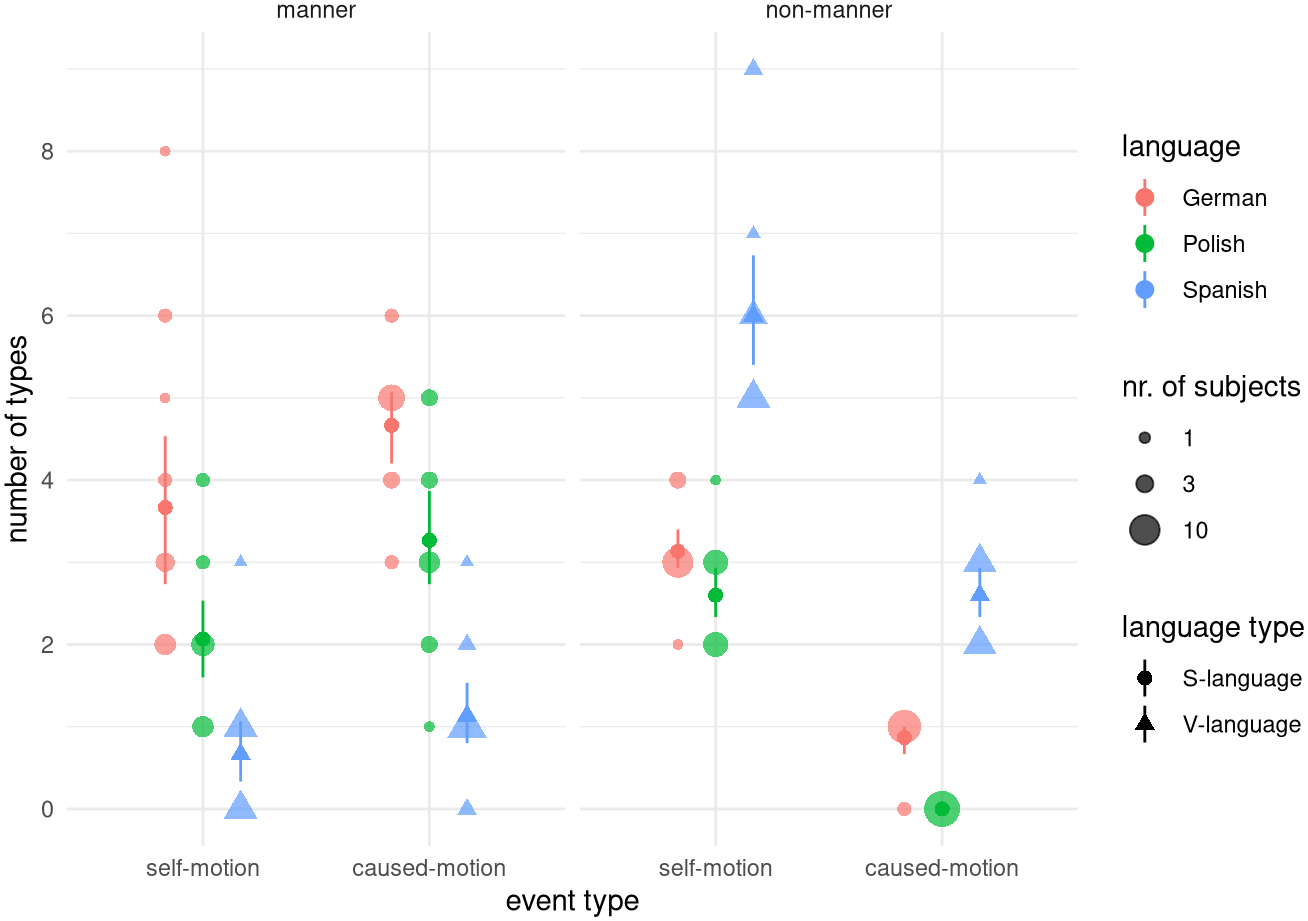

Turning next to verb types, we first analyzed inter-typological variability and found the expected contrasts in the expression of motion events: German and Polish speakers produced a significantly greater variety of manner verbs compared to Spanish speakers in both their self- (Spanish vs. Polish: W =1 95.5, p < .001; Spanish vs. German: W = 218, p < .001) and caused-motion descriptions (Spanish vs. Polish: W = 208.5, p < .001; Spanish vs. German: W = 224, p < .001); see Figure 2 for a summary of our results for verb types.

Fig. 2. The number of verb types.

Note. Each blob corresponds to a set of speakers using the same number of types in the given combination of variables. The number of speakers per blob is indicated by its size. Error bars are bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Our analysis also confirmed the predicted intra-typological variation: German speakers produced a greater variety of manner verbs than Polish speakers when talking about both self- (W = 176, p = .003) and caused-motion (W = 182.5, p = .001). This pattern is consistent with earlier work on intra-typological variation between Slavic and Germanic languages in the expression of self-motion (Kopecka, Reference Kopecka, Hasko and Perelmutter2010; Lewandowski & Mateu Reference Lewandowski and Mateu2016; Slobin et al., Reference Slobin, Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Kopecka and Majid2014), and extends this earlier work to the domain of caused-motion, indicating that intra-typological variation in S-languages can be found across the two event types.

We last examined whether the production of verb types varied by event perspective (i.e., self- vs. caused-motion) and found evidence for an effect: German, Polish, and Spanish native speakers produced a greater variety of manner verbs in their caused-motion descriptions compared to self-motion descriptions (V = 583.5, p < .001). These findings thus extend previous results for manner tokens (Lewandowski & Özçalışkan, Reference Lewandowski and Özçalışkan2018) to manner types; see Table 7 in Appendix V for a complete list of manner and path verbs produced by speakers of each language.

4. Discussion

In this study, we asked whether speakers of German, Polish (both S-languages), and Spanish (a V-language) exhibit inter-typological, intra-typological, and language-internal variation in their linguistic construal of motion events. Our analysis of simultaneous verbalizations of an ongoing video sequence produced by 15 German, 15 Polish, and 15 Spanish adult native speakers provided compelling evidence for both intra-typological and language-internal, as well as inter-typological variability in the expression of motion.

4.1. inter-typological variation

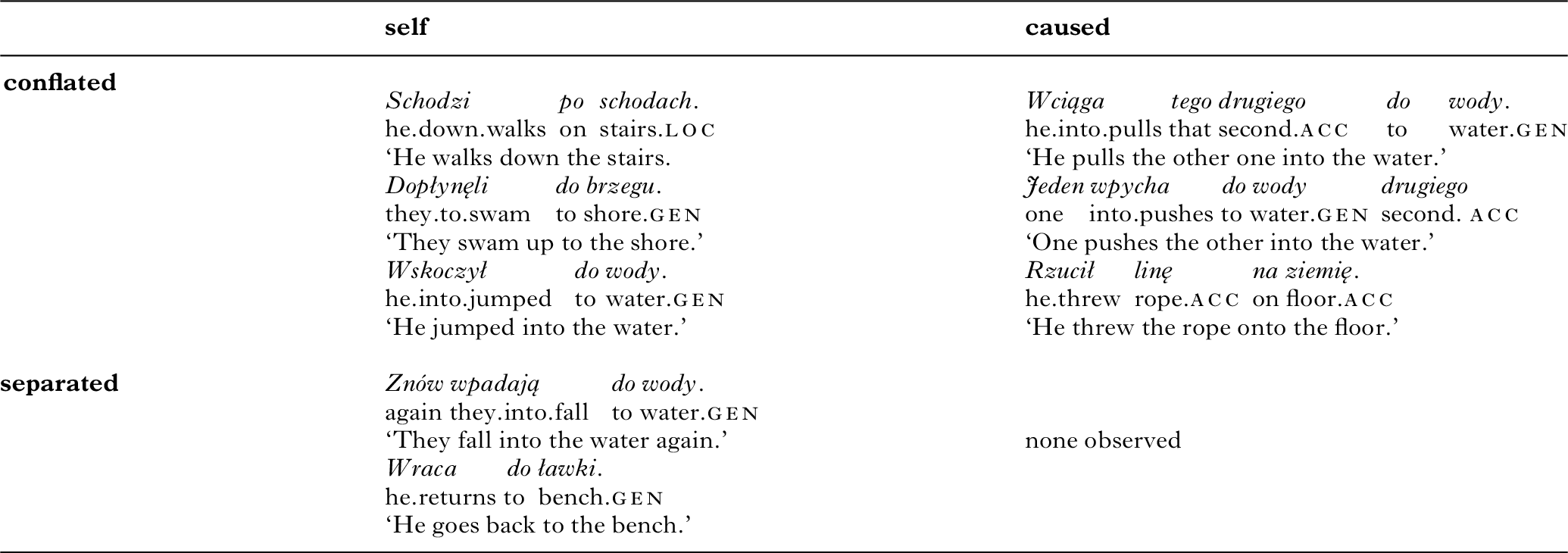

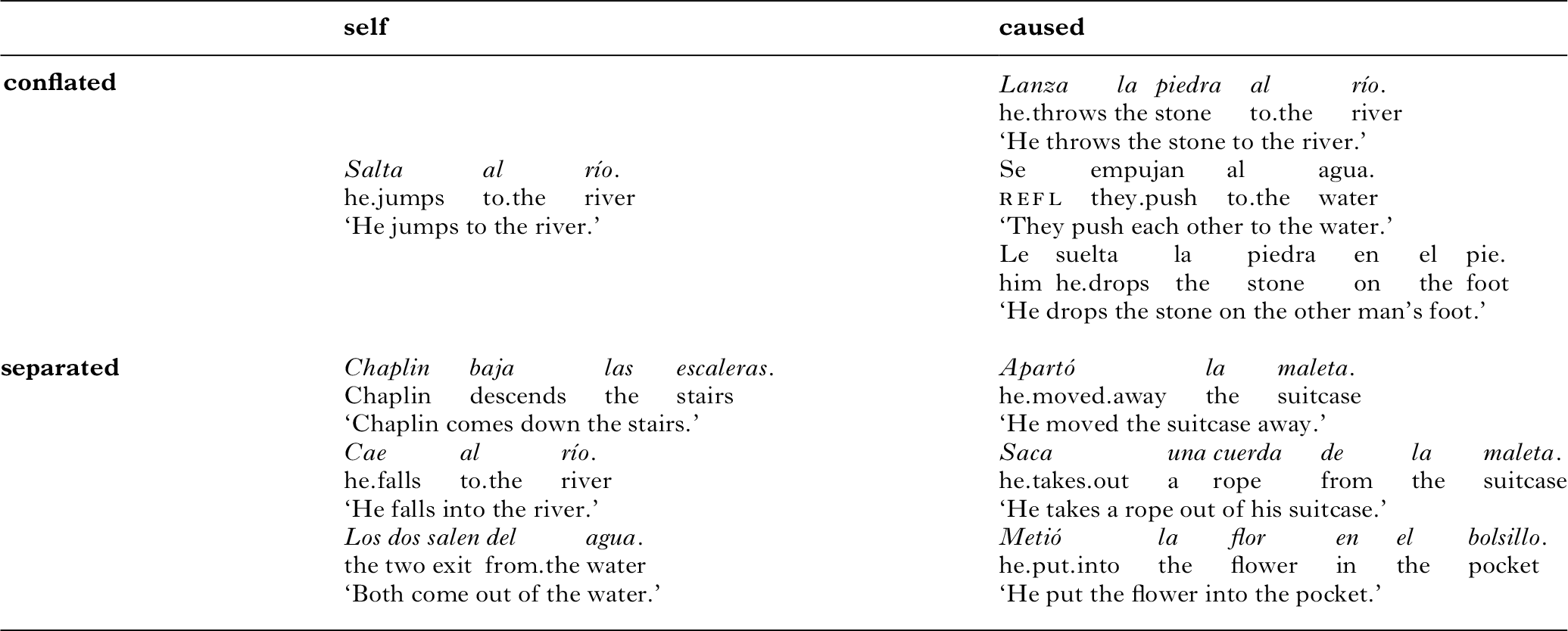

Starting with inter-typological variation, German and Polish speakers showed greater preference for manner types and tokens (i.e., the conflated strategy; e.g., Germ. Der Mann schreitet die Treppe runter ‘The man strides down te stairs’, Chaplin zieht ihn aus dem Wasser ‘Chaplin pulls him out of the water’; Pl. Dopłynęli do brzegu ‘They swam up to the shore’, Rzucił linę na ziemię ‘He threw the rope onto the floor’) than Spanish speakers, who mostly relied on the separated packaging strategy (e.g., Sp. Chaplin baja las escaleras ‘Chaplin descends the stairs’, Apartó la maleta ‘He moved the suitcase away’). This pattern was consistent across the two event types, i.e., self- and caused-motion. As such, our analysis provides empirical evidence that the previously observed typological differences between V- and S-languages in the expression of self-motion (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Özyürek, Kita, Brown, Furman, Ishizuka and Fujii2007; Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994; Strömqvist & Verhoeven, Reference Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004) extend to caused-motion events, a finding that is consistent with earlier work by Hendriks and Hickmann (Reference Hendriks and Hickmann2015), Hendriks et al. (Reference Hendriks, Hickmann and Demagny2008), and Ji et al. (Reference Ji, Hendriks and Hickmann2011).

4.2. intra-typological variation

Turning next to intra-typological variation, we found that German speakers produced greater diversity of manner verbs (i.e., verb types) than Polish speakers regardless of event type. This pattern was reversed for the number of manner verbs (i.e., verb tokens), with German speakers showing lower reliance on manner tokens than Polish speakers when talking about both self-and caused-motion.

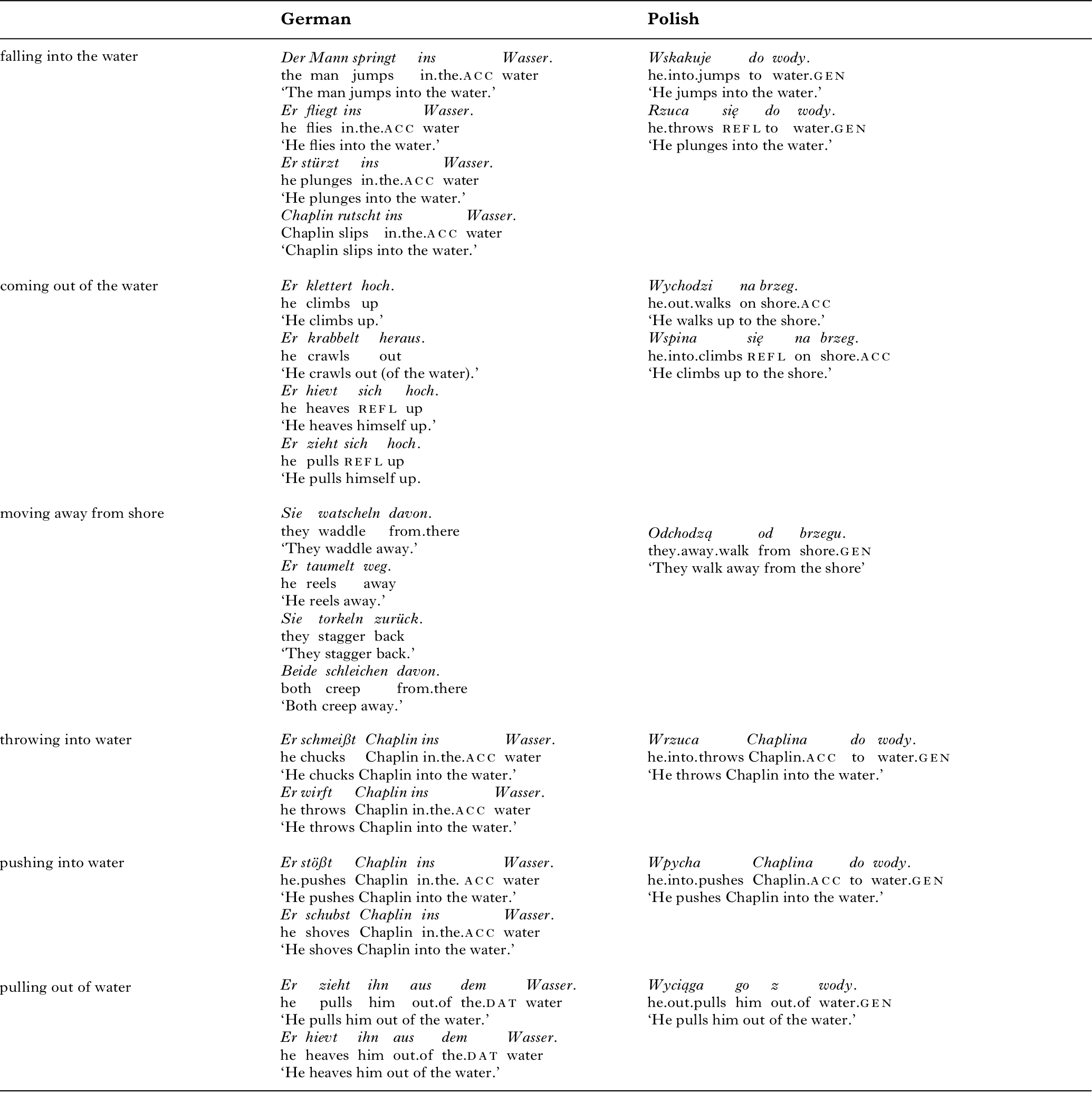

With regard to type frequency, our data indicate that the contrasting use of manner types between German and Polish was not random but followed a specific pattern. While both German and Polish speakers made extensive use of general manner verbs (i.e., first-tier verbs according to Slobin’s, Reference Slobin, Bybee, Thompson and Haiman1997, classification; e.g., Germ. Und dann springen sie rein ‘And then, they jump into’; Pl. Wkoczyli do wody ‘They jumped into the water’; Germ. Er wirft seinen Stock weg ‘He throws his stick away’; Pl. Wrzucił Chaplina do wody ‘He threw Chaplin into the water’), German speakers relied on more specific manner verbs (i.e., second-tier verbs according to Slobin’s, Reference Slobin, Bybee, Thompson and Haiman1997, classification; e.g., ‘stagger’, ‘stumble’, ‘nudge’, ‘thrust’, etc.) at higher rates than Polish speakers; see also, e.g., Cifuentes-Férez (Reference Cifuentes-Férez2010) and Slobin et al. (Reference Slobin, Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Kopecka and Majid2014), for further classifications of different types of Manner. Therefore, German speakers used a narrative style that is richer in Manner specifications (i.e., more granular Manner descriptions) compared to Polish speakers. How can we explain the existence of different degrees of Manner granularity in languages than belong to the same typological group? We propose that two closely inter-related factors are at work here: (i) codability effects, such as constraints on Manner/Path combinability and accessibility of manner verbs in the lexicon, and (ii) attention allocation during verbalization (i.e., thinking-for-speaking; Slobin, Reference Slobin, Gumperz and Levinson1996).

Starting with codability effects, Polish speakers had no choice but to exclude from their motion descriptions many of the Manners used in the German narratives due to heavy restrictions on Manner/Path combinability (e.g., Germ. Er hat Chaplin ins Wasser reingeschubst ‘He nudged Chaplin into the water’ vs. Pl. *wszturchnąć ‘nudge into’; Germ. Er stolpert hinaus ‘He stumbles out’ vs. Pl. *wypotknąć się ‘stumble out’, etc.). Footnote 1 This finding is consistent with earlier work (Filipović, Reference Filipović2007; Lewandowski & Mateu, Reference Lewandowski and Mateu2016) that demonstrated that prefixes, the typical locus of Path encoding in Polish (Kopecka, Reference Kopecka2004; Lewandowski, Reference Lewandowski2014a, Reference Lewandowski2014b, Reference Lewandowski2020) show more restricted compatibility with verbs than particles and prepositional phrases, the typical locus of Path encoding in German (Bamberg, Reference Bamberg, Berman and Slobin1994; Harr, Reference Harr2012).

A smaller inventory of manner verbs in Polish is another possible reason why Polish speakers produced fewer Manner types than German speakers. For example, verbs such as schmeißen ‘chuck’, shieben ‘thrust’, hieven ‘heave’, hüpfen ‘hop’, widely used by German speakers, could not have been employed by Polish speakers for the simple reason that no direct equivalents are available in the Polish lexicon. We know from previous studies on inter-typological variation in the expression of motion that grammatical restrictions on Manner encoding have an effect on the size of the manner-of-motion lexicon. S-languages, with Manner encoded in the main verb, have a richer lexicon of manner verbs than V-languages, which typically encode Manner in an optional adjunct (Slobin, Reference Slobin, Hickmann and Robert2006; Verkerk, Reference Verkerk2013). Our study thus extends these earlier findings by suggesting that, even within the same typology, languages can have diverse manner verb lexicons, depending on the grammatical restrictions they impose on the lexicalization of Manner.

Turning now to the effects of attention allocation during verbalization, Polish speakers attended to a smaller variety of Manner distinctions than German speakers even in cases where a Polish equivalent of a German verb could have been used. For example, German speakers frequently employed verbs such as ‘slip’ (e.g., Der Stein ist runtergerutscht ‘The stone slipped down’), ‘rip’ (e.g., Der Mann hat Chaplin die Schnur aus der Hand gerissen ‘He ripped Chaplin’s cord away’), ‘pack’ (e.g., Er hat alles ins Koffer gepackt ‘He packed everything into the suitcase’), and others. Although these verbs are available in the Polish lexicon, and, importantly, they can readily combine with prefixes (e.g., ześlizgnąć się ‘slip down’; wpakować ‘pack into’; wydrzeć ‘rip away’), they were not used by Polish speakers. It follows, then, that Polish speakers were attuned to a smaller range of Manner dimensions than German speakers, even if no codability restrictions were imposed by the linguistic system. This observation is consistent with Slobin’s (Reference Slobin, Gumperz and Levinson1996) thinking-for-speaking hypothesis, and extends its applicability to the domain of intra-typological variation. According to Slobin (Reference Slobin, Gumperz and Levinson1996), typological variation affects cognition, particularly during online production of speech. More specifically, the habitual way of encoding events biases speakers to those conceptual components of the event that are easily codable in the language they speak. For example, when talking about motion, speakers of S-languages pay greater attention to the Manner of motion than speakers of V-languages, an attentional bias that results from the codification of Manner in different clausal constituents (i.e., main verb vs. adjunct, respectively). As such, the speakers’ choice to include certain properties of the event while omitting others depends not only on how salient the property is but also on how easily encodable the property is in a given language. Following this line of reasoning, it can be claimed that German speakers displayed stronger attentional bias toward specific Manner dimensions compared to Polish speakers because German provides more accessible means, both lexical and morphological, for the expression of specific Manner distinctions than Polish.

Nevertheless, despite the greater diversity of manner verbs in German narratives, German speakers relied on a smaller number of manner verbs (i.e., manner tokens) than Polish speakers. Why, then, was the lexicalization pattern found for verb types reversed for verb tokens? One possible explanation is that, when describing motion scenes, German speakers relied on path tokens to a larger extent than Polish speakers, resulting in a lower proportion of manner tokens in German compared to Polish. Specifically, the German participants commonly employed two path verbs in their descriptions of self-motion, namely fallen ‘fall’ (e.g., Er ist ins Wasser gefallen ‘He fell into the water’) and kommen ‘come’ (e.g., Er kommt aus dem Wasser ‘He comes out of the water’), and one path verb in their descriptions of caused-motion, namely holen ‘bring, fetch’ (e.g., Er holt das Seil ‘He brings the rope’). Only the equivalent of fallen ‘fall’ was used by the Polish group (e.g., Wpadł do wody ‘He fell into the water’), because Polish has no equivalent for the deictic path verbs kommen ‘come’ and holen ‘bring, fetch’ (Lewandowski, Reference Lewandowski2007, Reference Lewandowski, Navarro i Ferrando and López2010, Reference Lewandowski2014c). Having fewer path verbs at their disposal, Polish speakers had no alternative but to increase their use of manner verbs. For example, to convey the content of kommen, the Polish group systematically used the basic manner verb chodzić ‘walk’ combined with a path satellite (e.g., Mężczyzna wychodzi z wody ‘The man comes out of the water’, lit. ‘The man walks out of the water’), thus increasing the number of manner tokens but not manner types.

These results are contradictory to those presented in the study by Lewandowski and Mateu (Reference Lewandowski and Mateu2016), who found that German motion descriptions not only included more manner types but also more manner tokens than Polish motion descriptions. One factor that might explain this divergence is the difference in research design. Lewandowski and Mateu compared German and Polish translations of Tolkien’s The Hobbit. They focused on nine passages with particularly rich manner information. As such, when adapting the source text to the target language, translators had no alternative but to make frequent use of manner verbs to preserve the semantic content of the original passages. Our study, on the other hand, required participants to provide a free description of motion scenes, thereby allowing them the opportunity to exclude Manner from their narratives.

4.3. language-internal variation

Turning last to language-internal variation, we found that speakers across the three languages encoded a significantly greater number (i.e., manner tokens) and variety (i.e., manner types) of Manner distinctions in the main verb in their caused-motion descriptions compared to their self-motion descriptions. Previous research showed that caused-motion events elicit a higher number of manner verbs than self-motion events (Hendriks & Hickmann, Reference Hendriks and Hickmann2015; Lewandowski & Özçalışkan, Reference Lewandowski and Özçalışkan2018; Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan2005). Our results thus extend these previous findings by showing that, when talking about caused-motion, speakers not only increase their use of manner tokens but also manner types.

However, why do caused-motion events show a higher degree of Manner encoding than self-motion events? Self-motion refers to an agents’ self-instigated movement and, as such, it only includes one participant, i.e., the Figure. In contrast, caused-motion events describe other-instigated movement and, as such, they include one further participant, namely, an external force that causes the Figure to move. As a consequence, while self-motion events can only specify the way in which the Figure moves (i.e., Manner of motion, e.g., He jumped into the water), caused-motion events are able to specify both the way in which the Figure moves (e.g., John rolled the ball across the room) and the way in which the figure is caused to move (i.e., Manner of causation; e.g., John kicked the ball across the room); see, e.g., Rappaport Hovav and Levin (Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Butt and Geuder1998). Therefore, the possibility of expressing this additional piece of information may have been one reason why speakers across the three languages increased their use of manner verbs in their caused-motion descriptions. In fact, Manner of causation is one important feature that constitutes an essential semantic attribute of the majority of caused-motion verbs involved in our study (e.g., Germ. schubsen ‘push, nudge’, stoβen ‘push, bump’, werfen ‘throw’, etc.; Pl. pchać ‘push’, rzucać ‘throw’, (s)trącić ‘knock (over)’, etc.; Sp. empujar ‘push’; soltar ‘drop’, tirar ‘throw, pull’, etc.).

However, encoding Manner dimensions in the main verb in Spanish caused-motion descriptions (e.g., Tiró la piedra al agua ‘He threw the stone into the water’, Empujó a Chaplín al río ‘He pushed Chaplin into the river’, etc.) is at odds with the fact that V-languages typically lexicalize Path but not Manner in the main verb. One plausible explanation for this pattern could be that caused-motion events bring about a strong notion of dynamicity (Rohde, Reference Rohde2001). Specifically, given that the external agent exerts force upon the Figure to initiate its movement, it also determines the spatial source of the motion event, thus supplying a sense of directionality. We have some evidence from previous work that manner verbs that evoke directionality can occasionally appear in self-motion descriptions in V-languages (e.g., Sp. correr a la cocina ‘run to the kitchen’, saltar al agua ‘jump into the water’ vs. *bailar a la cocina ‘dance to the kitchen’, *tambalear a la habitación ‘stagger into the room’; Lewandowski & Mateu, Reference Lewandowski and Mateuforthcoming; Naigles et al., Reference Naigles, Eisenberg, Kako, Highter and McGraw1998; Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan2015; Pedersen, Reference Pedersen, Boas and Gonzálvez-García2014). Our results thus extend these earlier findings by indicating that directional manner verbs can be found in motion constructions across the two event types, i.e., self- and caused-motion, in V-languages.

Surprisingly, we also observed that German and Polish speakers showed a pronounced tendency toward the use of non-manner verbs (i.e., the separated packaging strategy) in their self-motion descriptions, a pattern that is not fully in line with earlier research, which exposed a clear inclination toward the conflated lexicalization strategy among speakers of S-languages (e.g., Strömqvist & Verhoeven, Reference Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004). For example, some of the scenes included in our elicitation task could have been described in two ways: either by employing a manner verb combined with a path satellite (i.e., conflated strategy) or by encoding Path information only (i.e., separated strategy): cf. Germ. Er gleitet ins Wasser ‘He slides into the water’ vs. Er fällt ins Wasser ‘He falls into the water’, Er kriecht die Kante hoch ‘He crawls up the ledge’ vs. Er kommt aus dem Wasser raus ‘He comes out of the water’; Pl. Wrzuca się do wody ‘He plunges into the water’ vs. Wpada do wody ‘He falls into the water’. Both German and Polish speakers showed preference for the latter strategy: only 65 out of 257 German and 101 out of 224 Polish self-motion descriptions were Manner/Path conflated clauses.

It should be noted, however, that previous studies typically did not require participants to respond with the added pressure of restricted time, while our elicitation task (i.e., a simultaneous commentary of an ongoing video clip) naturally resulted in heavy time constraints on the subjects’ responses. We know from psychological research that humans process information selectively by focusing on properties that are more central and tuning out those that are more peripheral (Pashler, Reference Pashler1998). We also know that time pressure may additionally intensify reduction of information processing (Maule, Hockey, & Bdzola, Reference Maule, Hockey and Bdzola2000). Consistent with these findings, our results may indicate that speakers tend to reduce the conceptual complexity of motion events as a way to adapt to time constraints. Because Path constitutes the core element of a motion event (Talmy, Reference Talmy2000), it logically follows that both German and Polish speakers were biased toward excluding Manner (and not Path) from their narratives. An alternative explanation could be that there is a general tendency in oral narratives, independent of time constraints, to omit Manner information if an alternative Path-only strategy is available and Manner is not particularly relevant to the discourse (see Filipović, Reference Filipović2007; McNeill & Duncan, Reference McNeill, Duncan and McNeill2000; Stefanowitsch, Reference Stefanowitsch, Goschler and Stefanowitsch2013, for similar phenomena in other S-languages). Further research is needed to understand the relative effect of time constraints on the speakers’ choice of lexicalization patterns.

4.4. general discussion

Taken together, our findings suggest that the extent to which Talmy’s (Reference Talmy2000) typology exerts itself in language use is influenced by additional factors that expand the binary distinction between V- vs. S-languages. The locus of Path encoding (i.e., verb vs. prefix vs. particle/prepositional phrase) gives rise to inter- and intra-typological variation, while event type (self- vs. caused-motion) gives rise to language-internal variation. In addition, speech modality (e.g., oral vs. written narratives; narratives with vs. without time constraints, etc.) appears to be a third important factor influencing the packaging of motion elements – a possibility that remains to be further explored in future work.

Starting with inter- and intra-typological variation, our data strongly indicate that the locus of Path encoding affects the expression of Manner. Spanish, typically conveying Path in the main verb, imposes the tightest typological constraints on Manner encoding. In contrast, German and Polish, which lexicalize Path outside the main verb, leave the verb free to encode Manner. However, there is a split between Polish, typically expressing Path in morphologically bound prefixes, and German, typically expressing Path in morphologically independent particles and prepositional phrases. Specifically, Polish imposes heavier restrictions on Manner codability than German, resulting in distinct ‘thinking-for-speaking’ patterns, with Polish speakers attending to less diverse Manner dimensions than German speakers. These results are consistent with earlier work which provided some evidence that speakers of languages such as Russian, Serbian, and Latin, which typically encode Path in prefixes, convey less specific Manner distinctions than speakers of languages such as English, Dutch, and Swedish, typically conveying Path in particles and prepositional phrases (see Filipović, Reference Filipović2007, for Serbo-Croatian and English; Iakovleva, Reference Iakovleva2012, for Russian and English; Koptjevskaja-Tamm et al., Reference Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Divjak, Rakhilina, Hasko and Perelmutter2010, for Russian, Polish, English, Dutch, and Swedish; and Iacobini & Corona, Reference Iacobini and Corona2016, for Latin). In addition, we know from work on lexical semantics and construction grammar that in languages such as English and German, both typically encoding Path in particles and prepositional phrases, motion constructions are particularly flexible in that they not only combine with motion verbs but also with non-motion verbs lexicalizing highly specific Manner information (e.g., Eng. Rainwater whistled into the house, He crashed his car into a cemetery; Germ. Das Fahrrad ist in die Altstadt gequietscht ‘The bike squeaked into the old town’, Er schmetterte den Ball über das Netz ‘He smashed the ball over the net’; see Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995; Haselbach, Reference Haselbach2018; Levin, Reference Levin1993). Consistent with our findings, these verbs are banned from occurring in motion constructions in languages such as, for example, Polish and Russian, which both typically encode Path in prefixes (e.g., Pl. *Wświsnął do pokoju ‘He whistled into the room’, *Whuknął samochód do cmentarza ‘He crashed his car into a cemetery’; Rus. *Velosiped v”skripel v staryj gorod ‘The bike squeaked into the old town’).

That being the case, the observed differences in Manner expression between German and Polish may illustrate a broader division between S-languages that typically encode Path in morphologically bound elements such as prefixes (e.g., Polish, Russian, Serbian, Latin) and S-languages that typically encode Path in morphologically independent elements such as particles and prepositional phrases (e.g., German, Dutch, English, Swedish). It could be hypothesized, then, that the tighter the link between Path and the main verb, the less the ability to encode Manner and, conversely, the looser the link between Path and the main verb, the more the ability to encode Manner. That is, on one extreme would be V-languages, in which Path and verb are the same element. These languages impose the tightest restrictions on Manner encoding by allowing only a limited set of directional manner verbs to occur in the main verb slot. Next to these languages would be S-languages in which the locus of Path is an element that is morphologically bound to the verb, i.e., a prefix. These languages encode more specific Manner information than V-languages but impose fairly tight restrictions on motion verbs encoding rich Manner information. Finally, at the other extreme would be S-languages in which the locus of Path is an element that is morphologically independent from the verb, i.e., a particle and/or a prepositional phrase. These languages allow the encoding of a particularly wide variety of Manner dimensions.

However, consistent with language-internal variability, motion constructions associated with morphologically bound and morphologically free elements can co-exist in a given language. For example, although German predominantly encodes Path in particles and prepositional phrases, this language also uses (to a lesser extent) directional prefixes. In line with the restrictions on Manner/Path combinability outlined above, German prefixes typically combine with a narrower range of manner verbs than German particles and prepositional phrases (Lewandowski & Mateu, Reference Lewandowski and Mateuforthcoming). As such, strictly speaking, the constraints on Manner encoding apply to particular constructions rather than to particular languages.

It should be stressed, however, that there is not necessarily a positive correlation between diversity and number of manner verbs. For example, German speakers produced more manner types but fewer manner tokens than Polish speakers in their directed motion descriptions. Conversely, Polish speakers produced fewer manner types but more manner tokens than German speakers, when talking about both self- and caused-motion. We proposed that this pattern arose, primarily, as a result of greater use of path verbs in German compared to Polish. More important, these findings show that, while the locus of Path encoding seems to be a good predictor of Manner diversity in motion descriptions, the amount of Manner information may be dependent on additional factors. As such, future work examining these additional factors is needed to gain a better understanding of the extent to which Manner is encoded in the two types of S-languages.

Turning now to language-internal variability, our findings showed that not only languages as a whole but also different event types (argument structure constructions in Goldberg’s, Reference Goldberg1995, terms) within particular languages can display variable degrees of Manner salience. For example, our data, along with evidence from earlier research (Lewandowski & Özçalışkan, Reference Lewandowski and Özçalışkan2018; Özçalışkan, Reference Özçalışkan2005), suggest that caused-motion events elicit greater diversity and number of manner verbs than self-motion events regardless of language type, which is a pattern that we attributed to differences in event structure between self- and caused-motion. Our study also demonstrated that speakers of S-languages may convey Path in the main verb at higher rates than one might expect on the basis of Talmy’s (Reference Talmy2000) typology, particularly when describing self-motion events. We suggested that one possible factor leading to an extensive use of path verbs in S-languages may be related to constraints on processing time – a hypothesis that remains to be further investigated.

Slobin (Reference Slobin, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004) proposed that the world’s languages can be arranged along a cline of Manner salience, with some languages encoding more specific Manner distinctions than others. Our study adds to this line of research by showing that Manner salience is a more complex and nuanced issue than it may seem at first glance: there can be significant differences between variety vs. amount of Manner information encoded in a given language, and the same language can also show different degrees of Manner saliency depending on event type.

These findings may prove fruitful for future research on linguistic relativity. According to linguistic relativity, the structure of a language influences the way its speakers view the world (Lucy, Reference Lucy, Gumperz and Levinson1996; Whorf, Reference Whorf and Carroll1956). As mentioned before, Slobin (Reference Slobin, Gumperz and Levinson1996) proposed that language-specific patterns in the encoding of motion affect non-verbal cognition – but only during online language processing (thinking-for-speaking). Studies examining the effect of inter-typological contrasts in the encoding of self-motion on visual perception, similarity judgments, and gesture provide empirical support for Slobin’s hypothesis. For example, when visually inspecting a motion scene, or when comparing two motion scenes that differ either in Manner or Path, participants displayed a bias toward either Manner or Path, depending on their language type, if the task involved verbal encoding. However, they did not display such bias if the task did not involve verbalization (Gennari et al., Reference Gennari, Sloman, Malt and Fitch2002; Hohenstein, Reference Hohenstein2005; Papafragou, Hulbert, & Trueswell, Reference Papafragou, Hulbert and Trueswell2008). In a similar vein, participants showed language-specific gesture patterns only when gesture was produced with speech (i.e., co-speech gesture), but not when gesture was produced without speech (Özçalışkan et al., Reference Özçalışkan, Lucero and Goldin-Meadow2016).

It is likely, of course, that the preferred lexicalization patterns have no or little long-term effect on non-verbal cognition. However, the presence of such effects has been exposed for at least some other cognitive domains, such as color (Regier & Kay, Reference Regier and Kay2009), number (Gordon, Reference Gordon2004), time (Boroditsky, Reference Boroditsky2001), object position (Koster & Cadierno, Reference Koster and Cadierno2018), spatial frames of reference (Brown & Levinson, Reference Brown and Levinson1993; Pederson et al., Reference Pederson, Danziger, Wilkins, Levinson, Kita and Senft1998), and count/mass distinctions (Imai & Gentner, Reference Imai and Gentner1997), etc. (see Gleitman & Papafragou, Reference Gleitman, Papafragou and Reisberg2013, for a recent review). As such, it is also possible that the motion lexicalization patterns that are supposed to be prototypical in a given language type (i.e., either V- or S-framing) are simply not ubiquitous enough to influence non-linguistic thought (Goschler & Stefanowitsch, Reference Goschler and Stefanowitsch2013; Pavlenko & Volynsky, Reference Pavlenko and Volynsky2015). This possibility should not be ruled out. Hence, future work should take into account not only the coarse-grained inter-typological contrasts but also the more nuanced intra-typological and language-internal variability in order to advance our understanding of the relationship between language and motion cognition. For example, earlier work on the effects of lexicalization patterns on non-verbal cognition in S- vs. V-languages largely focused on self-motion events (e.g., Papafragou et al., Reference Papafragou, Hulbert and Trueswell2008; Özçalışkan, Lucero, & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Özçalışkan2016). However, the domain of self-motion might not be a good testing ground for cognitive biases toward Manner in S-languages because, as our study showed, speakers of S-languages may rely on the Manner/Path conflated pattern far less frequently than is commonly assumed. The domain of caused-motion, in contrast, may be a more promising avenue for investigating the effects of S-framing on non-linguistic conceptualization, because in language use manner verbs (i.e., the conflated pattern) might be more ubiquitous in caused-motion events as opposed to self-motion events.

The assumption that Manner and Path form uniform categories is another possible limitation that might have skewed the results of studies on linguistic relativity. With respect to Manner, a more fruitful line of inquiry might be one that focuses on those manner types that are particularly salient in a given language. For example, it is unlikely that speakers of S-languages encoding path in prefixes will display cognitive bias toward highly specific Manner information given its relatively low frequency in discourse. However, the opposite may prove true for languages encoding path in morphologically independent elements (i.e., particles, prepositional phrases), given that these languages systematically encode more elaborated Manner distinctions.

In conclusion, our study suggests that the two-way distinction between S- and V-languages may be insufficient to not only identify the whole range of variation in the encoding of motion events but also to test the effects of language on motion cognition. Although we only focused on three languages, German, Polish, and Spanish, our results suggest, in line with earlier work (e.g., Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Reference Ibarretxe-Antuñano and Guo2009; Slobin, Reference Slobin, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004), that the ways in which motion is encoded in these languages may be characteristic of a more nuanced typological classification than the dichotomy of V- and S-languages. Specifically, languages such as Hebrew, Japanese, and Turkish pattern together with Spanish and hence belong to the V-framed type. Next, languages such as Latin, Russian, and Serbian pattern together with Polish and hence belong to the ‘weak’ type of S-language, lexicalizing path in morphologically bound elements. Finally, languages such as English, Dutch, and Swedish pattern together with German and hence belong to the ‘strong’ type of S-language, lexicalizing path in morphologically independent elements. Therefore, future work that extends our findings to these groups of languages is needed to advance our understanding of variation patterns in motion event encoding and their effect on motion cognition.

Appendix I

Table 1. Sequence of events in the video stimulus

Appendix II

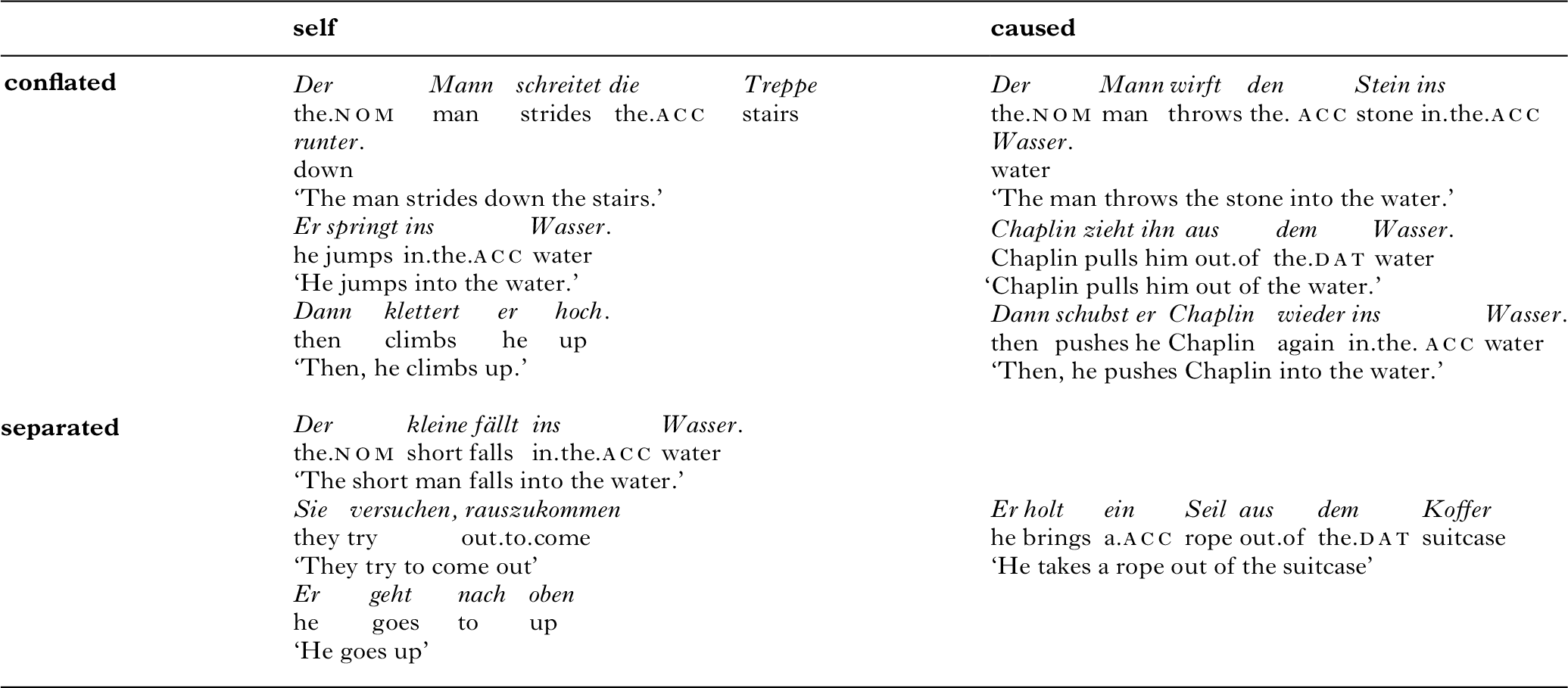

Table 2. Examples of self- and caused-motion descriptions produced by German native speakers

Table 3. Examples of self- and caused-motion descriptions produced by Polish native speakers

Table 4. Examples of self- and caused-motion descriptions produced by Spanish native speakers

Appendix III

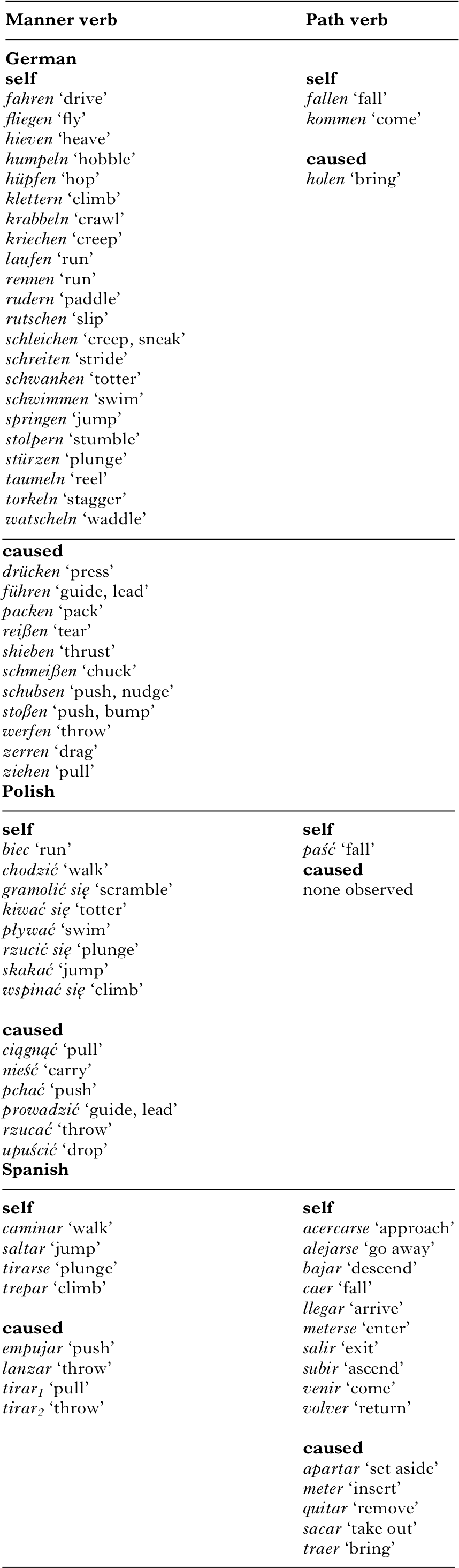

Table 5. Examples of Manner descriptions provided by German vs. Polish native speakers

Appendix IV

Table 6. Mean number of clauses with separated (i.e., Path-only or Path and Manner in separate clauses) and conflated (i.e., Manner and Path in a single clause) packaging of motion components produced by German, Polish, or Spanish speakers

Appendix V

Table 7. Manner and path verbs used by German, Polish, and Spanish speakers