Not many composers can claim to have been active on three continents. Hans-Joachim Koellreutter managed this feat, while not only pursuing what he regarded as a universal musical idiom but at the same time responding to the cultural specificities of each location in which he found himself. His varied career illustrates the role played by migrants in constructing a global diasporic network that is constitutive of musical modernism. Koellreutter's life and work have primarily been researched from the perspective of his contribution to the music of Brazil, where he spent the greatest part of his career, and, to a lesser extent, in the context of the emigration of composers and musicians from Nazi Germany and occupied Europe. Less attention has been paid to Koellreutter's work in India and Japan and his contribution to global musical modernism. As a composer, teacher, organizer, and diplomat, he devoted his life to international understanding and overcoming of national prejudices. The consequences he drew, however, drove him to embrace a form of universalism that was at odds with the increasing ideological polarization of the 1970s and 1980s, notably in a Latin American intellectual climate dominated by dependency theory.

Studies in Europe

Most of what we know about Koellreutter's biography is based on his own testimony, which raises the issue of ‘self-representation’ discussed by Charles Wilson, among others.Footnote 1 This has to be borne in mind during the following. Hans-Joachim Koellreutter was born in 1915 in Freiburg in southwestern Germany, the son of Emma Maria and Wilhelm Heinrich, a doctor. His mother died in 1918 during the influenza epidemic. Trouble started in 1923, when his father married again; Hans-Joachim never got on with his stepmother. He has himself described his discovery of music as an accident, an anecdote that also illustrates his rebellious nature: not accepting the social inequality between school pupils, he collected money from wealthier children to buy chocolate bananas for poorer ones. When the former complained that he had ‘stolen’ the money, he was put under house arrest for months. He found an old flute, and, lacking anything else to do, taught himself to play.Footnote 2

These proto-socialist and anti-authoritarian instincts put him at odds with his family: his father was a die-hard monarchist, and his uncle Otto Koellreutter would become one of the leading Nazi jurists. Although a mediocre pupil, Koellreutter finished grammar school in neighbouring Karlsruhe in 1934.Footnote 3 His father wanted him to study in Leipzig, which had a conservative reputation, but Hans-Joachim simply changed onto the train to Berlin; the city had not lost its subversive appeal even under the Nazis. He studied flute with Gustav Scheck, choral directing and composition with Kurt Thomas, and piano and musicology. He also took a course given by Paul Hindemith in open adult education (Volkshochschule).Footnote 4 The significance of this connection is contested. In an interview with Irene Tourinho, Koellreutter downplayed Hindemith's importance, declaring that this was ‘something that had entered every bibliography [recte: biography?] about me and that is not correct: They say I was a student of Hindemith! I attended an extension course [curso de extensão] Hindemith gave on the new theory, but I was one of many!’Footnote 5 On the other hand, Daniela Fugellie as well as Angela Ida de Benedictis and Veniero Rizzardi report, seemingly independently of one another, that Hindemith played a major role in Koellreutter's teaching (indeed that of a ‘patron saint’, in his student Edino Krieger's words), both in Brazil and in Italy (see below).Footnote 6 In any case, Koellreutter's library (held at the Fundação Koellreutter (henceforth FK)) contains, in addition to many of his scores, some of Hindemith's writings, including Unterweisung im Tonsatz, the first volume of which was published in 1937 and which Koellreutter may have brought with him. He would therefore not have had to exclusively rely on direct contact.

With Dietrich Erdmann, Ulrich Sommerlatte, and Erich Thabe he founded the Arbeitskreis Neue Musik (New Music Workshop). In his monumental encyclopaedia, Fred K. Prieberg mentions that the group performed Hindemith's Violin Sonata in E in June 1936, when Hindemith was already persona non grata.Footnote 7 The holdings at the FK also include a leaflet by the chamber music trio for old and new music Pro Musica, which includes rave reviews from Berlin, Karlsruhe, Freiburg, Amsterdam, and Paris, suggesting that Koellreutter toured internationally early on (Thabe was a member of this group too).Footnote 8

Koellreutter soon came into conflict with the authorities again. Here, too, Hindemith played a role. As Fugellie has shown, Koellreutter is among the signatories (listing ‘flute’ as his main subject) of an open letter addressed to the director of the Hochschule für Musik, Fritz Stein, in support of the composer who faced hostility in the press.Footnote 9 At that time, Hindemith was composing the opera Mathis der Maler. The Mathis Symphony, compiled from material for the opera, had been premiered to great acclaim by the Berlin Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwängler, the leading conductor of the era, on 12 March 1934, but the composer's attempts to find a suitable opera company willing to produce the work ran into difficulties, mostly due to his earlier association with Weimar modernism. In an ill-considered plan, Furtwängler wrote a newspaper article in support of Hindemith, which the Nazis could only interpret as open insubordination. In response, the conductor was forced to resign from most of his positions (although he regained many of them not long afterwards), while Hindemith took unpaid leave from his professorship at the Hochschule, accepting an invitation from the Turkish government to help them reform music education in the country soon after. He avoided burning bridges, however, and there was a period of mutual accommodation with the Nazis before he finally emigrated first to Switzerland in 1938, followed by the United States in 1940.Footnote 10

The open letter was posted on 3 December 1934, in the wake of Furtwängler's article, which had appeared on 25 November. At that point, Koellreutter would only just have started his studies, and he was able to continue until 1936: it would appear as if the Nazis were not entirely unforgiving, at least during this relatively early stage. According to Goldenbaum, it was Koellreutter's refusal to join the Nazi Party that led to his expulsion from the Hochschule in 1936; in the interview with Tourinho, the composer named a student organization instead of the NSDAP itself, although the gist is much the same.Footnote 11 Fugellie has not been able to find any evidence for that in the institution's archive, however.Footnote 12

Around this time, Koellreutter met the German conductor Hermann Scherchen, one of the leading propagators of new music, who had emigrated to Switzerland in 1933. In his own words: ‘the person who led me to new music was [not Hindemith but] the conductor Hermann Scherchen. … And the discussion about dodecaphony went on everywhere.’Footnote 13 The circumstances are not entirely clear: Goldenbaum makes it seem as if Koellreutter had met Scherchen already in Germany and, around Christmas 1936, joined him in Switzerland, where he continued his flute studies at the Conservatoire of Geneva with Marcel Moyse, the great French flautist, who taught there alongside the Paris Conservatoire. It seems more plausible, however, that he moved to Switzerland, continued his studies with Moyse and subsequently met Scherchen, although this has to remain inconclusive. His studies with Moyse lasted until 1937.Footnote 14

There was another personal matter which made staying in Germany impossible: Koellreutter got engaged to Ursula Goldschmidt, who was half-Jewish. Having to return to Berlin to renew his passport, he was told that he had been reported to the Gestapo (the secret police) for Rassenschande (‘racial dishonour’ or miscegenation) – the complainant had been his father! (Curiously, though, Koellreutter would dedicate his Música 1941 to his father.Footnote 15) He was given two days to resolve the engagement and to enter military service. Instead, Koellreutter got a false passport (how is not reported) and got back to Switzerland. During the next couple of months, he accompanied Scherchen on conducting courses in Geneva, Budapest, and Neuchâtel.Footnote 16 In addition, he performed widely across Europe, according to Kater covering ‘Germany, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Italy, Poland and Czechoslovakia, among others’ – all on a false passport, apparently. A particular highlight came on 9 February 1937 in Lausanne, when he performed Milhaud's Sonatina for Flute and Piano accompanied by the composer.Footnote 17 One of Koellreutter's students from the last period of his life, Emanuel Dimas de Melo Pimenta, also reports that Koellreutter witnessed the first performance of Alban Berg's Violin Concerto at the ISCM Festival 1936 in Barcelona.Footnote 18 This is not mentioned anywhere else in the literature, and there are a couple of inaccuracies in the account which might raise suspicions, but it is certainly possible, considering, in particular, that the conductor was none other than Scherchen (standing in at late notice for the indisposed Webern).

In Budapest, Koellreutter met the Brazilian ambassador and his wife, who helped him to emigrate to South America and organized a tour for him. He arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 16 November 1937 and immediately fell in love with the country and, above all, its people:

It was shocking. I knew the whole of Europe, but it always seemed the same. There was another world here, and I had to learn and experience and learn how to live here. But I liked that. I toured all over Latin America, but I chose Brazil. Not because of the country, but because of the people, I liked them immensely. I liked them very much.Footnote 19

Somewhat surprisingly for a political refugee, what Koellreutter overlooked in this assessment is the political context. Just days before his arrival, on 10 November 1937, President Getúlio Vargas used the pretext of the so-called Cohen plan, a fictitious communist plot, to stage a coup d’état: he declared a state of emergency and dissolved the legislature with the use of military police. So began the Estado Novo (named in reference to the Salazar regime in Portugal), a period of dictatorship with fascist tendencies that lasted until 1945.Footnote 20

To sum up the first, European phase of Koellreutter's career, his formal training was not very extensive, having studied from 1934 to 1937, with some additional disruption due to his abrupt change from Berlin to Geneva. This may be surprising considering the importance that teaching would have in his later career. Furthermore, his primary activity was as a flautist. Beyond this, his connection with Scherchen, as his student-cum-assistant, would prove significant. By contrast, there is no evidence that he was active as a composer. The FK hosts a small number of juvenile compositions, written before Koellreutter's formal studies (although one undated composition could potentially be from a later phase), which show promise but little distinction. Although he studied composition alongside choral conducting with Kurt Thomas, a recently appointed choral composer at the Hochschule in Berlin, this would probably have been elementary composition as a part of general music studies, not professional training. Ligia Amadio similarly states that there is only one composition from Koellreutter's studies, Mondnacht for four-part male choir on a poem by Eichendorff, which is strictly tonal, seemingly in line with a compositional exercise.Footnote 21 It was not before he came to Brazil that Koellreutter could be considered a composer.

Beginnings in Brazil

On his arrival in Brazil, Koellreutter debuted as a flautist in 1938 with a recital at the Conservatoire of Belo Horizonte, followed by a tour through the north of the country, Argentina and Uruguay with the pianist Egydio Castro e Silva (not quite ‘all over Latin America’ as he stated but extensive enough). In the same year, he married Ursula Goldschmidt and commenced his teaching career at the Brazilian Conservatory in Rio. Despite its grand title, this was a private music school founded the previous year by the composer Oscar Lorenzo Fernández. In addition, he made the acquaintance of Theodor Heuberger, a fellow German immigrant and influential entrepreneur and patron.

Meanwhile, the German authorities had not forgotten him: the documents in the FK include his draft papers from the overseas department of the military (falsely labelled Guia de condução, ‘driving license’, in the archive's catalogue), also indicating that Koellreutter was registered with the embassy.Footnote 22 By 1942, his nationality was revoked, however, although he was only officially notified of this in a letter from 1958.Footnote 23

The following years were filled with restless activity, given the pressure of providing for a young family. Apart from his teaching job, Koellreutter worked in a printing company and played in the Restaurant Danúbio Azul (Blue Danube) at night; for the latter, he also learned saxophone, taking lessons from Luiz Americano, one of the leading popular musicians of the time.Footnote 24

He fairly quickly established a composition class, many of whose students would evolve into leading figures in Brazilian musical life, including Cláudio Santoro (1919–89), Edino Krieger (1928–2022), and César Guerra-Peixe (1914–93); they were later joined by Nininha Gregori (1925–), Geny Marcondes (Koellreutter's second wife, 1916–2011), Eunice Katunda (Catunda) (1915–90), and Roberto Schnorrenberg (1929–83). Fugellie points out that Koellreutter's students won many prestigious awards and scholarships early on, at both national and international levels. As a result, his reputation rested at least as much on the success of his students as on that of his own compositions.Footnote 25 Indeed, he had little training or experience as a composer himself. His first recognized compositions were Improviso e Estudo (Improvisation and Study) for solo flute (1938) and Sonata 1939 for Flute and Piano.Footnote 26 Improviso e Estudo has been re-edited by the FK; it is in extended tonality in a Hindemithian vein, centred on A minor, although neither of the two movements ends on the tonal centre.Footnote 27

In 1938, Música Viva was founded, which spearheaded contemporary music in Brazil. Apart from Koellreutter and his students, this included the musicologist Luiz Heitor Corrêa de Azevedo (1905–92), the pianist Egydio de Castro e Silva (Koellreutter's duo partner), and the composers Brasílio Itiberê II (1896–1967), Luís Cosme (1908–65), and Octavio Bevilacqua (1887–1959). The title is a tribute to Scherchen, who had founded the Musica Viva journal in Brussels (1933–6) and a Musica Viva orchestra in Vienna (1936), alongside other organizations called either Musica or Ars Viva. As an organization, Musica Viva organized concerts, newsletters and later even radio programmes. Apart from Scherchen's model, there are also clear parallels to Conciertos de la Nueva Música, founded in neighbouring Argentina in 1937 and re-named Agrupación Nueva Música in 1944. Its spiritus rector was Juan Carlos Paz, the first Latin-American serial composer, who would become a comrade-in-arms of Koellreutter. Another significant contact was their common friend Francisco Curt Lange, a fellow German immigrant and musicologist, who lived between Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay.

According to Carlos Kater, there were distinct phases in Música Viva's existence. Like its Argentinean counterpart, it supported contemporary music as a whole during its early phase in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Even the godfather of Brazilian composition – and major collaborator of the Vargas regime – Heitor Villa-Lobos could be persuaded to act as honorary president. From around 1944, Música Viva took a more partisan stance in favour of the avant-garde and against the prevailing nationalist school.Footnote 28 Problems began to appear in 1948, with the Second International Congress of Composers and Music Critics held in Prague. Santoro and Katunda attended the event and were deeply influenced by the Zhdanovite doctrine of Socialist Realism, leading to splits and the eventual dissolution of Música Viva.Footnote 29

In 1940, Koellreutter had to move to São Paulo when the printing company he worked for was taken over by a rival. From then on, he would live between the two Brazilian metropoles. He soon contracted lead poisoning, however. During his convalescence, he was supported by Heuberger, who also gave him a position in his art gallery on his recovery, which allowed Koellreutter to give up his work as a printer. Another regular visitor was a close friend from this period, who would become his greatest enemy: Mozart Camargo Guarnieri (1907–93), the nationalist composer.

Dodecaphony

Around this time – after the founding of Música Viva but before its more militant phase – Koellreutter makes what, for many, is his decisive contribution: introducing dodecaphony in Brazil and beyond. Although, in retrospect, such a judgement risks lending too much weight to a particular, arguably arbitrary technical innovation, it should not be forgotten to what extent serialism became associated with the international modernist avant-garde at the time and, in particular, with opposition to and exile from, the Nazi regime. It makes sense to speak of a ‘dodecaphonic diaspora’ in this context.Footnote 30

This raises the question of Koellreutter's own command and use of the method. As outlined, his first compositions were tonal. According to his own testimony, it was his then-18-year-old student Claudio Santoro who showed him a symphony for two string orchestras with proto-serial elements, thus motivating him to share the knowledge he had gained from Scherchen and explore it compositionally himself.Footnote 31 His first serial composition was an Invenção (1940) for woodwind trio (flute, clarinet, and bassoon), which is also notable for polymetric passages.Footnote 32

The most widely discussed work from this period is Música 1941 for piano, and it is worth studying this in detail to understand Koellreutter's approach to serial composition. The FK has both digitized the original published edition and produced a new digital edition, and there is also a recording on YouTube.Footnote 33 Following the work of Ligio Amadio (or so it seems), the existing literature cites a fundamental row: D, E♭, F, C, B, G, A, A♭, D♭, B♭, E, G♭.Footnote 34 It remains unexplained how this has been identified, considering that the only occasion it is used in its entirety is at the beginning of the third movement, and here too it is split vertically over two parts and includes a number of dyads, so the actual order of pitches remains uncertain. There is, however, a series of sketches with row tables which establishes the fundamental row and a variant derived from it (see below), but this appears to have been made available only recently.Footnote 35 That said, Amadio studied with Koellreutter, so the identity of the series may have been communicated by him; but no explanation is provided.

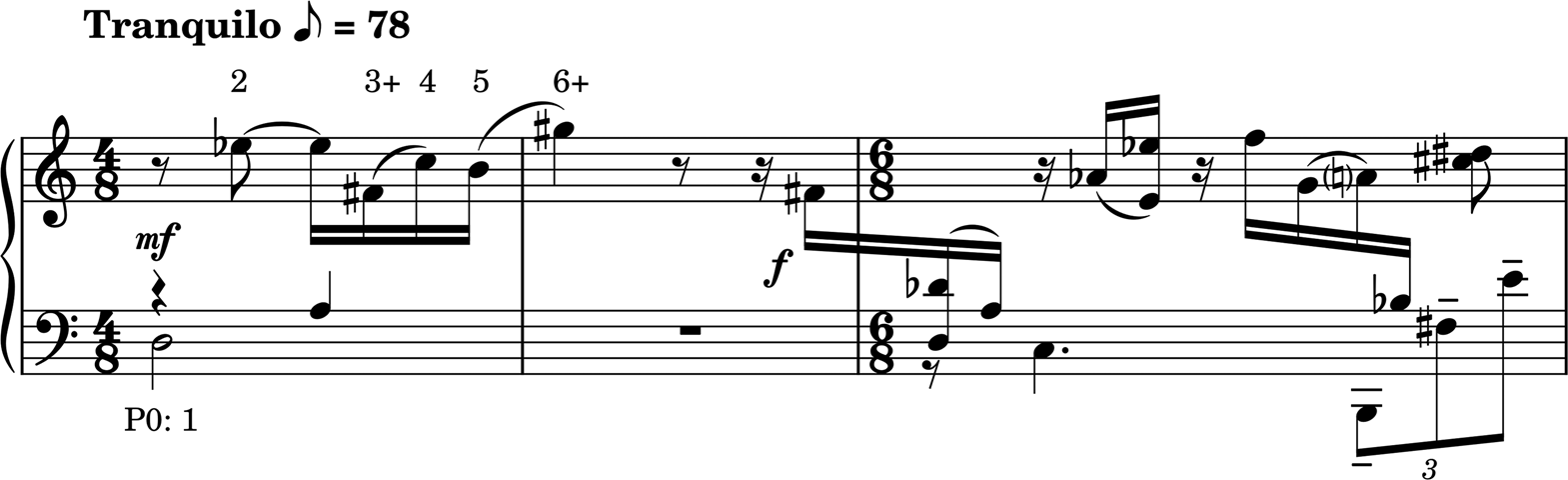

Whatever the origin and foundation of this row, the problem for an analytical approach is that the twelve-note collection is rarely employed systematically, let alone in any particular order. To explain this, we only need to look at the beginning of the piece (Example 1). This establishes the following pitch classes: D, E♭, A, F♯, C, B, G♯. This is far from accurate, but the identity is recognizable. The next pitch class is F♯, however, which has already been sounded and thus seems to militate against twelve-tone rules. Given that the section is in two parts, the possibility of two simultaneous serial strands could be considered, although the two F♯s are in the same part. In any case, whatever assumptions are made, it is very difficult to find any consistent serial order in the first movement: only at the very end does the music run through the first eight pitch classes of the fundamental row in order. Amadio and Braz Gado offer several explanations: the use of row fragments, permutations of the serial order, gapped series, and even chromatic alterations. Some of these are common even in more orthodox twelve-note composition, but the last one, in particular, jeopardizes the integrity of any serial structure, and in combination, they appear to undermine it altogether.

Example 1. Koellreutter, Música 1941, beginning, final printed version.

The FK has published the sketches and manuscripts for the composition, and these provide further insight.Footnote 36 In particular, there are two earlier versions of the opening. One is on page 1; I will start, however, with another, which begins on page 7.Footnote 37 There are reasons to believe that this is the first draft: whereas the version of the beginning on page 1 shows distinct similarities with the final, published score, this one is substantially different; it is also quite sketchily written, with many corrections and erasures. This putative first version starts with a complete linear unfolding of the fundamental row across the two hands, starting on a d held in the left hand, to which the right hand adds e♭1, which is followed by pitches 3–10 of the row in a regular semiquaver run, until the final two notes of the row – e and f♯ (g♭) – are sounded again in the left hand (Example 2). What then of the remaining notes in the left hand in bar 1? G♯ (A♭) – A–B outline the beginning of P6 (a tritone transposition of the fundamental row), with G♭ and F added vertically, at which point this unfolding appears to end – although C♯–D–E♭ in the bass in bar 3 could be seen to continue this line (the repeated d must be part of the unfolding of P0). The mid-register (‘tenor’) semiquaver counterpoint starting in bar 2 outlines P10, starting with the fifth note and continuing until the end. In other words, there are simultaneous unfoldings, with the fundamental row being complemented by two of its incomplete transpositions.

Example 2. Koellreutter, Música 1941, beginning, first draft version.

This appears to be supported by (barely legible) figures added in the manuscript (identified in italics on the example). Next to the opening D3 there is a ‘1’, standing for the fundamental row (as opposed to the nowadays more common, albeit counterintuitive, serial nomenclature, which starts counting at 0). Next to the G♯ (A♭), there is a ‘7’, corresponding to P6 (again, if counting from 1 instead of 0). Likewise, in bar 2, P10 is indicated by ‘11’. Further, continuing the semiquaver counterpoint in the tenor from the end of bar 2, we find I2 (the inversion of the fundamental row on E): E–E♭–D♭–G♭–(G, omitted)–B–A–A♯ (B♭)–F. This, too, is indicated by a ‘3’. (For full disclosure, there is also ‘5’, which I have not been able to explain.)

In the second version, the semiquaver unfolding of the fundamental row in the right hand is cut short, with the G flipped an octave higher and sustained, creating a more expressionist gesture (Example 3). With the exception of D3 and A♭ / G♯, the left-hand elements are excised. As a result, the fundamental row is abandoned after only six pitch classes, and the simultaneous unfolding of P6 after one (which is obviously nonsensical in serial terms). The material in bar 2 appears unrelated to the opening, and its connection to the fundamental row, if any, is likewise unclear, although the bass may be based on I8. The published version is clearly based on the second one but introduces further changes (Example 1). F and G from the fundamental row are changed to F♯ and G♯, respectively, and A♭ in the left hand to A. As mentioned, the chromatic alteration of notes from the series is an aspect of Koellreutter's technique raised by Amadio and Braz Gado.Footnote 38 At the same time, the metre is shortened to 4/8, meaning that the climax of the opening gesture arrives on the downbeat of bar 2. In this way, the serial basis of the movement is practically entirely obscured in the published version by successive phases of revisions that leave no part of the musical structure, including the integrity of the series, untouched, thus making a mockery of common – if problematic – claims that the presence of a twelve-note series guarantees ‘structural unity’. As we have seen, however, the starting point was a fairly orthodox dodecaphonic approach. For what it is worth, Amadio and Braz Gado point out that the second movement of the piece is based on a ‘derived’ (Braz Gado) or ‘chromatic’ (Amadio) version of the series that is generated by interpolating notes from the second half of the fundamental row within the first half.Footnote 39

Example 3. Koellreutter, Música 1941, beginning, second draft version.

As outlined, Música 1941 is not Koellreutter's first composition, nor his first foray into serial technique. Nevertheless, it is tempting to observe a significant development between the three movements. The first features an often-awkward mixture of expressionist – or would-be expressionist – gestures like the opening and remnants of an essentially tonal language, if with ‘wrong notes’. One particularly conspicuous, recurring element is semiquaver motion in a zig-zagging contour, always starting on the second semiquaver of a crotchet beat, played in both hands in octaves, which is derived from the opening. The rhythmic inertia and hollow sound of the unaccompanied octaves seem incongruent in the context of the serial language, however modified. The second movement is built on the contrast between an atmospheric lyrical sound world established in the opening in pp and a more dramatic gesture in f. While the former reveals a subtle sonic imagination, the latter once again relies on unaccompanied octave doublings with a Tchaikovskian flavour that seems oddly out of place in the atonal context. Only the final movement achieves stylistic consistency and integration, within an idiom reminiscent of Schoenberg's early and middle twelve-note periods. Speaking of Schoenberg, the Viennese master is supposed to have approved, as Adolph Weiss reported in a letter to Koellreutter's friend Lange: ‘Schoenberg and I enjoyed many of the publications, especially the work of Señor Koellreutter’.Footnote 40

WWII and its aftermath

Despite ideological affinities with the Axis powers and against the blatant pro-Nazi sympathies of the military, Brazil entered WWII on the side of the Allies in 1942.Footnote 41 As a result, Koellreuter briefly found himself interned as an enemy alien (the immediate cause appears to have been a ‘suspicious’ payment from Lange, another German, for work carried out for the Instituto Interamericano de Musicología).Footnote 42

In 1943, Koellreutter landed a teaching job at the Music Institute of São Paulo, and, in 1944, a position in the recently founded Orquestra Sinfônica Brasileira (OSB) in Rio. The latter was secured through the personal support of its founding chief conductor, Eugen Szenkar, a Hungarian immigrant whom Koellreutter is supposed to have known from Europe.Footnote 43 This allowed him to finally give up non-music-related jobs.

It also seems to have given him more time for composition. Koellreutter focused particularly on vocal music at that time. A particularly attractive example is Nocturnes for medium voice and string quartet (1945) on poems by Oneyda Alvarenga, an influential figure in the cultural life of São Paulo at the time. The five songs of aphoristic brevity are set entirely syllabically, following the declamation of the verse, with an emphasis on note repetition, small intervals and mostly short rhythmic values. Larger intervals and sustained notes are rare and therefore lend emphasis to the words in question. The accompaniment is sparse, changing between thick chords, often with multiple stopping, and short melodic fragments in individual instruments. Owing to Koellreutter's practice of revisions and the predominance of chordal textures, the serial basis of the work is hard to detect. To use the opening of the first song as an example, the piece starts with a series of three tetrads in the strings (Example 4). Note, however, that they do not add up to the twelve-tone aggregate and that some pitch classes (D, C♯, and E) are repeated before that is complete, so it is doubtful that this is the result of a serial unfolding. What is also noteworthy is the quasi-tonal nature and minor modality of the tetrads, possibly indebted to Alban Berg whom Koellreutter particularly admired: the first can be understood as a minor chord with major seventh (4–19 (0148) in pitch-class set parlance); the second as a minor seventh chord in third inversion (4–26 (0358)), and the third as minor chord with major ninth (4–14 (0237)), in fourth inversion. Later chords appear as variants of these opening sonorities, although no systematic derivation could be established.

Example 4. Koellreutter, Nocturnes for medium voice and string quartet (1945).

The composition was transcribed for voice and piano to ensure wider performances,Footnote 44 and it acted as something like Koellreutter's visiting card not only in Brazil, but also internationally: it was selected, in the original version, as the first Brazilian composition for the ISCM festival in Sicily in 1949.

Música 1947 for string quartet may be Koellreutter's final major composition using ‘classical’ twelve-note technique. In its sparse and dispersed texture, consisting mostly of short melodic cells, the work has a Webernian flavour, although a propensity for extremely large intervals appears more idiosyncratic, heralding a post-war aesthetic. The work is in three movements, played attacca (or one movement consisting of three separate sections: there are light double bar lines and tempo markings but no clear indications of distinct movements). In another nod to Webern, or, indeed, Bartók, there is an evident concern for symmetries. The second movement is an exact palindrome, although Koellreutter obscures this in the very centre – the moment when the music just heard would be starting to ‘move backwards’. In the first movement, bars 13–24 are a repetition of bars 1–12 (Examples 5 and 6), but with the instrumental roles exchanged and the melodic contours inverted; for instance, the very first line consists of c3♯6 followed by c1, two octaves lower and the double-stopping e♭–f5 in the opening register. This is echoed in bar 12 by the viola playing c♯, followed by c2 two octaves up and the double-stopped e♭–f (which is actually unplayable) again in the original register. There are similar games afoot in the third movement: the cello and first violin parts from bar 258 are a retrograde of the opening – another palindrome, although again, this is obscured in the middle and by the other two parts. From bar 259, the beginning of the second movement is restated and from bar 269 that of the first, before the composition ends with another reminiscence of the second movement. As in the previous cases, the serial structure is not apparent from the musical surface: this is where any similarity to Webern ends.

Example 5. Koellreutter, Música 1947 for string quartet, 1st movt, beginning.

Example 6. Koellreutter, Música 1947 for string quartet, 1st movt, bb. 13–18.

Música 1947 brings an intensive phase of composition to a close – I have only discussed a fraction of his output during this period. In the following years, there is the Chamber Symphony from 1949 that was only premiered during his residency in Berlin in 1964 (see below). This appears to have been lost. That loss may be coincidental, but in a conversation with Graciela Paraskevaidis, Koellreutter explained that he had destroyed many of his compositions and that, indeed, the survival of any scores is accidental; he believed that a composer should work for his own time and not be held back by the past.Footnote 45 Amadio even mentions two chamber symphonies, from 1948 and 1949, respectively, but it seems more likely that this is the same composition.Footnote 46 In addition, Koellreutter wrote a Fanfarra de Inauguração (Inauguration Fanfare, 1949) for three trumpets and three trombones for the opening of the Museum of Modern Art in São Paolo. That makes it an occasional work, and the nature of the composition does not suggest significant ambitions beyond that purpose on the part of the composer.

Travels to Europe

With the war over and reconstruction underway, Koellreutter was able to travel to Europe and re-establish connections with musical life there. A first step was the founding of a Brazilian section of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM). As Fugellie outlines, there had been plans for joining the ISCM since 1940, and this appears to have been one reason for seeking Villa-Lobos's collaboration as a figurehead of international renown.Footnote 47 But the ISCM was in virtual hibernation during the war, so these initiatives did not come to fruition before 1947, with Koellreutter acting as general secretary of the Brazilian section.Footnote 48

Before embarking on his journeys, Koellreutter, who must have been stateless for the last couple of years, acquired Brazilian citizenship.Footnote 49 His first trip took him to Italy and Switzerland, with a short detour to Karlsruhe, where he went to school. Characteristically, he did not travel on his own but brought a sizeable number of his students in tow, thus helping to forge multiple links. This would set the pattern for his future journeys. The first stop was in Venice where he assisted his mentor Scherchen in a conducting course and gave a seminar on a materialist aesthetics of music on the occasion of the Biennale in 1948. In a letter to Lange, Koellreutter expressed his enthusiasm not only about the reception he received but also the spirit of optimism and cultural reconstruction he encountered.Footnote 50 Another highlight was a course in twelve-note composition he gave in Milan, which was attended by Bruno Maderna and Luigi Nono, among others, and which led to the friendship between Nono and Eunice Katunda, who was among the students accompanying Koellreutter. As de Benedictis and Rizzardi point out, Koellreutter's influence is perceptible in Maderna's and Nono's compositions until the end of 1951, in the distinction, indebted to Hindemith, between ‘melodic’ rows consisting of ‘tense’ intervals, ‘harmonic’ rows with ‘calm’ intervals, and ‘compensated’ ones, balancing the two.Footnote 51 Considering Hindemith's hostility towards dodecaphony, this application of his theories seems paradoxical and also contrary to Schoenbergian principles (given that the emancipation of the dissonance arguably makes the polarity between ‘tense’ and ‘calm’ obsolete). Yet we have already seen that Koellreutter was equally influenced by Hindemith and the Second Viennese School, and, as previously mentioned, he had a particular preference for the music of Berg,Footnote 52 notably the Violin Concerto, which likewise integrates tonal reminiscences in the series.

The last stop on the journey took him to Locarno in Ticino, for the preparatory meeting for the first Twelve-note Congress, hosted by Wladimir Vogel, whom Koellreutter had met at the Biennale in Venice, along with Luigi Dallapiccola and Ricardo Malipiero, which led to the idea of the meeting.Footnote 53 Returning in December 1948, Koellreutter stayed in Brazil for only about three months before departing for Europe again, this time heading first to the ISCM Annual Festival in Sicily in April (1949), where his Noturnos represented Brazil. He then attended the First Twelve-Note Congress in Milan in May before taking part in the Darmstadt Summer Courses at the end of June and early July, where he gave a talk on Twelve-note Music in Brazil and directed a concert, including the Nonet of his student César Guerra-Peixe. He was particularly impressed by the Darmstadt Summer Courses, writing to congratulate Wolfgang Steinicke, the director, and going so far as to propose returning to Germany to work with him.Footnote 54

His next visit, in 1951, took him to the ISCM Festival in Frankfurt, where Quatro líricas grecas (1950) by his student Nininha Gregori was the only work by a Latin-American, before going to neighbouring Darmstadt for that year's Summer Courses, which also hosted the Second Twelve-note Congress. His talk at the Courses, ‘New Music in South America’, has been included in the anthology Im Zenit der Moderne and provides a good insight into his thinking at the time.Footnote 55 Here, he contrasts the nationalist school(s) to what he calls ‘new music’, focusing on his Argentinean friend Juan Carlos Paz and other representatives of Paz's Agrupación as well as his own Música Viva. This distinction Koellreutter likened to the simultaneity between succeeding epochs as represented by J. S. Bach and Stamitz – apparently oblivious of the fact that it was Stamitz who was considered the ‘progressive’ composer at the time, although later generations generally sided with the ‘conservative’ Bach. Koellreutter further distinguishes between the original nationalist school, represented here primarily by Villa-Lobos, from later, ostensibly more progressive developments, as in the work of Alberto Ginastera, Jacobo Ficher, Juan José Castro, Piá Sebastiani, Julián Ardevol and Camargo Guarnieri (curiously overlooking Mexico). Perhaps surprisingly, he shows less sympathy with the latter group arguing that they are ‘no longer capable of genuine primitivity’. As he continued, it seems ‘a tragic weakness of that generation of composers, who lie between the nationalist and the new schools, that, in their works, the living forces of folk music no longer refer back to those pure zones in which music and religion are identical’.Footnote 56 Finally, he bemoans the ‘renunciation, under pressure of party-political edicts, by some of the most talented and productive young Brazilians of the artistic and aesthetic principles they had hitherto represented and defended’ (a point to which we will return).Footnote 57 By this time, he had been viciously publicly attacked by Camargo Guarnieri, so his treatment of him in the talk is remarkably fair, even if Koellreutter did not entirely hide his reservations about the younger nationalist school – reservations that would have been expressed more forcefully by others at that time and place!

The ‘open letter’

Koellreutter's generally positive reception abroad contrasted with increasing isolation at home. This is epitomized in the ‘open letter’ (carta aberta) that Camargo Guarnieri published in November 1950, in which he railed against the ‘dangers’ of serialism:

Considering my great responsibilities, as a Brazilian composer, before my people and the new generations of creators in musical art, and profoundly concerned about the current orientation of the music of young composers who, influenced by misconceptions, joined Dodecaphonism – a formalist current which leads to the degeneracy of the national character of our music – I resolved to write this open letter to musicians and critics in Brazil. Through this document, I want to warn you about the enormous dangers that at this moment profoundly threaten the entire Brazilian musical culture to which we are closely linked. …

Introduced to Brazil a few years ago by citizens of countries where musical folklore is impoverished, dodecaphonism was warmly welcomed by some unprepared spirits. …

Dodecaphonism … is a characteristic expression of a policy of cultural degeneracy, a branch of the wild fig tree of cosmopolitanism that threatens us with its deforming shadows and whose hidden aim is the slow and harmful work of destroying our national character.Footnote 58

This is only an excerpt; the full text is some five pages long and short on arguments but full of invective. Koellreutter is not even mentioned by name, but it is not hard to guess who is meant by ‘citizens of countries where musical folklore is impoverished’ and the reference seems to have been all but universally understood. What is particularly disturbing are the antisemitic tropes, such as the mention of ‘cultural degeneracy’ and ‘cosmopolitanism’, the latter contrasted with ‘national character’, not made any less problematic by the fact that Koellreutter was not Jewish.

Unsubtle though the rhetoric was, it successfully appealed to the cross-section between the far right and the extreme left at the time, the opposite ends of the horseshoe aligning in their ‘anti-elitist’ populism. Although there are plenty of evocations of ‘the nation/national’ and ‘patriotism’, which, in Brazil as elsewhere, are typically associated with the right, there are also denunciations of dodecaphony (or ‘dodecaphonism’, as Camargo Guarnieri has it) as ‘anti-popular’, ‘cerebral’, and, crucially, ‘formalist’. The last point was the standard accusation from proponents of Socialist Realism, which had just been reaffirmed as Soviet cultural policy by Andrei Zhdanov, the party secretary in charge of culture, at the aforementioned Prague Congress. It may also not be coincidental that the only composer quoted by Camargo Guarnieri is Mikhail Glinka – to the effect that music is composed by the people; the composers only arrange it – who had been sanctified by Stalinist music historiography.Footnote 59 The manoeuvre should have been transparent, but it was successful: Santoro and Katunda, both members of the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB) and attendees of the Prague Congress, denounced their teacher and embraced folkloristic composition (although Katunda first attempted to reconcile avant-garde and folkloristic materials and procedures). Guerra-Peixe had started to use popular music earlier; unlike Santoro and Katunda, who had no background in traditional or popular music, he had been a popular musician before working with Koellreutter. Among Koellreutter's inner circle, it was mostly Krieger who supported his teacher unequivocally; the disappointment in some of his students expressed by Koellreutter in his Darmstadt talk has to be understood in this context. These divisions marked the end of Música Viva.

In response, Koellreutter invited Camargo Guarnieri to a public debate, to be held on 7 December 1950 in the Art Museum of São Paulo. There were reportedly 500 people in attendance, and the renowned writer Oswald de Andrade, author of the Anthropophagist Manifesto, was to be the chair.Footnote 60 Camargo Guarnieri, however, had bowed out, having departed for Rio the day before.Footnote 61 Deprived of the opportunity to respond directly, Koellreutter published an open letter of his own. Echoing Camargo Guarnieri's opening phrase, he speaks of his responsibility towards a new generation of composers and, in particular, his students, slyly exposing Camargo Guarnieri's pomposity: instead of minhas grandes responsibilidades (‘my great responsibilities’) he refers simply to minhas responsibilidades and he makes no claim towards speaking for ‘the people’ or as a ‘Brazilian composer’. His principal point concerns artistic freedom:

Not having, on the one hand, – like every other technique of composition – any other purpose but to help the artist to express himself and, on the other hand, serving the crystallization of any aesthetic tendency, the dodecaphonic technique guarantees absolute freedom of expression and the complete realization of the composer's personality. It is no more or less ‘formalist’, ‘cerebral’, ‘anti-national’ or ‘anti-popular’ than any other compositional technique based on traditional counterpoint and harmony.Footnote 62

He further describes dodecaphony as a ‘logical consequence’ of the increased chromaticism of previous periods and as a technique that, as such, is not linked to any particular style or aesthetic (both contestable claims). Not content with defending dodecaphony, however, he also goes on the offensive, arguing that, among other things, nationalist composition is an impoverishment and ‘refuge for mediocre composers’ (the same charge made by Camargo Guarnieri about dodecaphony), that, ‘with its gratuitous formulas borrowed from Russian-French colourism is unable to obscure its structural poverty and absence of creative power’.

What had ultimately caused Camargo Guarnieri's outburst remains a mystery. No doubt the aesthetic and ideological disagreement was genuine, and this period saw a hardening of positions not only in Brazil, but also in neighbouring Argentina and, for that matter, Europe or North America. At the same time, the personal nature and viciousness of the attack seems unwarranted, particularly between former friends. There have been persistent rumours of personal motifs, which were given some support by Koellreutter in his interview with Tourinho, in which he suggests that ‘some say it was the women who fought’ (a remark that does not reflect well on him).Footnote 63

Pedagogic initiatives and opportunities

Although the affair surrounding the ‘Open Letter’ must have been painful, it had the unintended side effect of boosting Koellreutter's profile. In a letter to Lange, he reports that his courses were full and that he received plenty of invitations from the media.Footnote 64

In the meantime, with the help of Heuberger, Koellreutter set up the Curso Internacional de Férias Pró-Arte, held in January and February (the summer season on the Southern Cone) in Teresópolis, a mountain resort near Rio, where the Austrian-born soprano Hilde Sinnek, who was connected to both Heuberger and Koellreutter, owned a property.Footnote 65 Koellreutter would serve as artistic director for the next ten years; the courses existed until 1989, which is quite a feat considering Brazil's political and economic instability. The courses are blatantly based on the Darmstadt model, although Heuberger and Koellreutter surpassed that in one crucial respect (in addition to the rather more attractive surroundings): the Curso was interdisciplinary and covered visual art, design, and architecture as well as music. Koellreutter also planned extensive exchanges with the Darmstadt Summer Courses, although, due mostly to lack of funding, this could only be realized on one occasion, when Gerd Kämper, the winner of the Kranichsteiner Musikpreis in piano 1952, was invited to the Curso of the following year.Footnote 66

Soon after, in 1952, Koellreutter founded the Escola Livre de Música de São Paulo Pró-Arte (Free School of Music), which he also directed and where he taught aesthetics, composition, harmony, and counterpoint. For the first time, he was able to put his ideas into practice. As is little known, in 1954, he even set up an electronic music studio, one of the first of its kind and almost certainly the first in Latin America, although limited resources in terms of equipment, funding, expertise, and time restricted the range, success, and impact of the activities. He himself moved on in the same year. Nevertheless, he was also able to host Pierre Boulez, then on a Latin America tour as music director of the Renaud-Barrault Theatre Company.Footnote 67

Also in 1954 Koellreutter founded the Seminários Internacionais de Música (International Seminars in Music) in Salvador de Bahia, which would become the Escola de Música e Artes Cênicas (School of Music and Performing Arts) at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBa). Bahia is known as the birthplace of the Tropicália movement of the late 1960s and many of the future stars, including Gaetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil studied at the UFBa. But the most significant connection is with Tom Zé, who studied for an advanced degree in music between 1962 and 1967.Footnote 68 He only overlapped with Koellreutter between 1962 and 1963, when the latter moved on (or back) to Germany (see below), but Zé has been forthcoming about the importance of the impulses received from Koellreutter personally as well as the creative environment of openness and experimentation that he managed to instil and that was continued by his successor, the Swiss composer Ernst Widmer.Footnote 69

Having, for the first time, achieved a stable institutional footing in Brazil, Koellreutter ventured into further activities abroad, such as a long tour through the United States, Europe, and Asia, combining performing, conducting, and lecturing, followed by a stint as visiting professor in composition and aesthetics at the Musashino College of Music in Tokyo in 1953, where, among other activities, he premiered the Divertissement sériel of his Argentine student Susana Baron-Supervielle from the São Paulo Escola Livre.Footnote 70 As he acknowledged in his correspondence with Satoshi Tanaka more than twenty years later (which will be discussed below), it was on this occasion that Koellreutter first heard gagaku, Japanese court music, which had such an effect on him that it influenced all his subsequent output – although he stresses that he never tried to imitate it.Footnote 71 During the trip he was also sought out by the composer Kikuko Kanai, who was interested in learning serial technique and who visited him back in São Paolo the following year.Footnote 72

As will have become apparent, these activities were not secondary for Koellreutter, who was at least equally committed to teaching and to enabling others to fulfil their ideas as he was in his own compositions. He composed very little during this period: there are no known outputs between the Chamber Concerto and Fanfarra de Inauguração (1949) and Mutações / Mutationen (Mutations) (1953) for orchestra, which is mentioned by Fugellie and Amadio, although the score for that seems to have been lost.Footnote 73 The FK holds a recording, however, which suggests a typical dodecaphonic sound world, although the extended lyrical lines and clear textures are at some distance from the often disjointed and fragmented textures of much post-WWII composition.Footnote 74 Amadio further lists Systase (1954) for flute solo, two, apparently fragmentary pages for which are contained in the dossier on Systáticas (see below) in the FK.Footnote 75 There seem to be both biographical and compositional reasons for this hiatus. Given all his travels, teaching, and organizing activities, it is hard to see how Koellreutter could have found time for composition. At the same time, his encounters with the international avant-garde at the ISCM festivals, the Twelve-tone Congresses and, most of all, the Darmstadt International Summer Courses must have led to a reappraisal. This period saw both the emergence of dodecaphony as a dominant, if contested tendency on the international scene and its overcoming by newer avant-garde tendencies, notably integral serialism. The latter famously burst onto the scene at the Darmstadt courses in 1951, although there is little indication that Koellreutter was immediately gripped. In any case, there is no obvious sense of a ‘crisis’; Koellreutter appears to have been content to focus on other activities than composing.

Indeed, the partial withdrawal from composition lasted until 1959/60. When Koellreutter did return, it was with a dramatically renewed musical language, even in comparison with Mutations. Systáticas for flute, drum, woodsticks, and agogo (the double bell instrument used by samba bands) from 1959 is another work for which no definitive score appears to be available. There are three drafts that consist of largely identical material that all look incomplete. Although it is difficult to draw conclusions on the basis of potentially fragmentary material, what is noticeable is a radical economy of means: there are only very few notes; and single lines, usually of only a handful of notes are interspersed with extended silences. This is a tendency that was already noticeable in Música 1947 but is now driven to extremes. The reason for this development may be found in Koellreutter's encounter with Japanese gagaku in 1953. In his correspondence with Satoshi Tanaka, he wrote that he found in it an ‘extreme concentration of expression, economy of means, renunciation of sensuality, clarity and precision, independence from a rationally governed concept of time, asymmetry, an open, variable form, and other things’ (see below), which he perceived as a confirmation of his existing beliefs. Concretion (1960) for oboes, clarinets, muted trumpets, bassoons, carillon (tubular bells?), celestas, xylophones, vibraphones, pianos, and gong is another instance. It is the first of his ‘essays’ (as he called his compositions from this period, avoiding the notion of ‘work’) in ‘planimetric composition’, by which Koellreutter is referring to ‘a technique of composition which organizes musical signs in multidirectional planes, the signs of a musical language that renounces melody and harmony, fixed points of reference, as well as dialectically opposed dualities, that is to say: consonance and dissonance, strong and weak time, first and second theme etc.’Footnote 76 The score consists of only three small pages of notation. There are three groups, each with a number of sections that can be played in any order, although the composition has to end on a gong stroke. The basic material is made up of sustained sonorities, whose precise temporal arrangement is left to the performers. The composer has been quoted in the Japanese press to the effect that the pitches are organized dodecaphonically.Footnote 77 Given that they are arranged predominantly vertically, this is difficult to assess, but this element of continuity to his earlier period is significant. Nevertheless, a recording held at the FK reveals the distance to the earlier Mutations: the ‘speech character’ of music that Adorno still found in early dodecaphony and that is clearly noticeable in the earlier work is largely gone, in favour of a more uncompromising, sparse and brittle sound world.Footnote 78

The principles involved seem closely related to other forms of aleatory technique at the time and the language of ‘renunciation of melody and harmony … consonance and dissonance’ seems strangely outdated. Even the Japanese inspiration is familiar from John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, which is not to deny the personal significance these discoveries had for Koellreutter or the legitimacy of the results. Yet, even if the technical elements are fairly commonplace, the aesthetics, with its extreme reduction of material and emphasis on stillness and silence is not; on the contrary, it seems to look forward to the sound world of La Monte Young, if not the Feldman, Scelsi, or Nono of the 1980s.

Fittingly, Concretions was composed for Koellreutter's visit to Japan in 1961, where it received its premiere. There is an invitation by the German Cultural Institute (not yet named Goethe Institute), co-hosted by H[idekazu] Yoshida, described as ‘President of the Institute of Twentieth-century Music’, which he had co-founded with Yoshirō Irino and others in 1957. Intriguingly, on the back, Koellreutter had noted the titles of Alain Daniélou's Northern Indian Music and Traité de musicologie comparée.Footnote 79 This is the first known contact between Koellreutter and the Goethe Institute, his future employer as will be seen, and they concerned Japan and India, his postings. This may well have been coincidental and only concerned a routine invitation to a passing minor dignitary, but it is conceivable that connections were made that would lead to Koellreutter's eventual appointment. At that point, he was still living in Brazil and any contacts with his native country seemed to have been sporadic. His return journey to Brazil took him to Taipei, Hong Kong, Djakarta, Teheran, and New Delhi, illustrating the extent of Koellreutter's travels.Footnote 80

Koellreutter's teaching activities also led to his first book publication. Anyone who was expecting a primer on serial composition or the like would have been disappointed, however: the book, which is very short (42 pages), is on jazz harmony.Footnote 81 This should not come as a surprise: while, according to most accounts, Koellreutter's teaching focused on traditional approaches, such as harmony and counterpoint, it was very open. Avant-garde approaches, including serial composition, were not generally favoured, let alone obligatory.Footnote 82 Among his students were many leading popular and jazz musicians: Tom Zé was already mentioned, but they also included Antônio Carlos (Tom) Jobim, the ‘father of bossa nova’ and composer of classics such as ‘Garota de Ipanema’ (Girl from Ipanema) and ‘Samba de uma Nota Só’ (One Note Samba), who studied with Koellreutter privately from as early as 1941.Footnote 83 Koellreutter's personal library, held at the FK, includes a good collection of relevant materials, although with a regional flavour: there is more Ary Barroso than Duke Ellington.

Return to Germany and Posting to India

In 1963, Koellreutter became programme director of the Goethe Institute (GI), the West-German cultural institute headquartered in Munich, a position he held until 1965. It is unclear what led to such a prestigious appointment: Koellreutter seems to have retained some ties to his homeland and to have been effortlessly effective at networking. Nevertheless, one would expect prior experience in a managerial position in the civil service or previous connections to the institution, but there is no obvious record of either, beyond the reception in Japan mentioned earlier. While, as Matthias Pasdzierny has shown, many West German institutions tried to attract returnees, there is no indication that this was true of the GI, and Koellreutter is the only person discussed in the book who was employed there.Footnote 84 In addition to any pull factors in favour of a return to Germany, there were also push factors. In 1961, the visionary director of the University of Bahia, Edgard Santos, who had overseen the founding of the Music Department, was deposed; he died soon after.Footnote 85 In 1964, Brazil descended into military dictatorship.Footnote 86

In 1964, Koellreutter embarked on a prestigious year-long fellowship from the Ford Foundation as artist-in-residence in Berlin; among the other fellows were Luciano Berio, Elliott Carter, Vinko Globokar, Hans Werner Henze, Roger Sessions, Igor Stravinsky, and Isang Yun.Footnote 87 The chronology of the two positions in Germany is a bit confused in the literature. Kater dates the fellowship to 1962 and hence before his position at the GI, but documents by the Berliner Künstlerprogramm show unequivocally that Koellreutter's fellowship was for 1964, although it is possible that he was awarded it two years before.Footnote 88 Both positions overlapped: a short biography issued by the GI on his accession to the post in Tokyo dates his role in Munich to 1963–5, therefore largely coinciding with his fellowship.Footnote 89

The residency would have allowed him to focus on composition. The immediate outcomes were Oito Haikais de Pedro Xisto / Acht Haikai des Pedro Xisto (Eight Haikai by Pedro Xisto; 1962) for bass voice and instruments and Kulka-Gesänge (Kulka Chants; 1964) for soprano and piano. Although the former must have been composed in Brazil, it was published in Germany; the latter was a direct fruit of the residency. Both pieces develop the principles established earlier in Concretion. The singer is often only given a pitch outline, leaving the exact durations of each pitch to their discretion. The instruments provide only occasional interjections. The elements of open form in Concretion are not repeated in these compositions, however: all elements have to be performed in their written order.

The fellowship also facilitated concerts of Koellreutter's music. Thus, on 22 October 1964, his Chamber Symphony (1949) was performed at the Akademie der Künste by members of Berlin's Radio Symphony Orchestra under Gilbert Amy, alongside compositions by Isang Yun, Elliott Carter, Iannis Xenakis, and Amy himself.Footnote 90 Another concert, given by the Kammerensemble Jeunesses Musicales on 29 January 1965, included the premiere of Koellreutter's Kulka-Gesänge and Musik 1944 (Música 1944) for Violin and Piano; the soprano in the former was his future wife Margarita Schack.Footnote 91 Schack performed the Kulka-Gesänge again a year later in Munich, possibly a belated result of Koellreutter's stay in the city.Footnote 92

In the same year (1965), Koellreutter was posted to India to direct the GI in New Delhi, which also covered (then) Ceylon and Burma.Footnote 93 In April 1966, he divorced his then current wife, Maria Angélica dos Santos Bahia, and married Margarita Schack in June.Footnote 94 One must assume that his day job was challenging enough, but he also set up the Delhi School of Music, where his wife also taught. As suggested before, however, teaching seems to have been a labour of love for Koellreutter. Judging by the brochures and programmes held at the Fundação Koellreutter, most if not all of the teaching at the school was a lot more basic than what he had been used to, and there are no indications that he taught composition, at least not at professional level. Although the school was specialized in Western music, there were courses in Indian music too, and it was included in most concerts. Indeed, Koellreutter learned every bit as eagerly as he taught: he took lessons with Pandit Vinay Chandra,Footnote 95 and his interest is also reflected in his personal library. Among the results are three compositions, Composition 68 (Sunyata), Advaita for sitar, table and chamber orchestra (his first compositions involving non-Western instruments), and India Report. He also wrote a short book on Indian music for his Brazilian students.

Composition 68 (Sunyata) for solo flute, small ensemble (some members of which are detuned by a quarter tone), and tambura is a fascinating example of Koellreutter's attempts to merge twelve-tone technique, his more recent ‘planimetric approach’ with the concomitant radical reduction of means and tendency towards stillness and a creative response to Indian music and culture. As in some other compositions from the time, there are several manuscripts representing variant versions, without any clarity about a ‘final’ or ‘definitive’ one. There appear to be four movements or sections, the first of which is an ‘alaap’ for solo flute. In South Asian music, the alaap is an unmetered, improvised prelude which introduces and explores the raga, the underlying mode. One sketch sheet headed ‘I’, which could refer to the section for which it is intended, features a twelve-note row, starting with the fifth B–E, the first note of which is labelled ‘vadi’, the fundamental note of a raga, and the second ‘samvadi’, the second most prominent note, typically, as here, a fifth from the vadi (see Example 7).Footnote 96 Whether a twelve-tone row can be treated like a raga is an open question, but it seems significant that this was Koellreutter's apparent intention. The alaap consists of a series of sustained notes the exact duration of which is to be decided by the performer. The succession of pitches does not exactly replicate the twelve-note row, although the connection is palpable. An actual alaap would likewise not necessarily introduce the notes of the raga in linear order, but herein also lies the problem, namely the difference between modes such as ragas and serial rows: for the former the succession of pitches is largely irrelevant (despite certain characteristic melodic formulae), whereas for the latter it is integral.

Example 7. Koellreutter, sketch for Composition 68 (Sunyata) showing a twelve-note row, Fundação Koellreutter.

The remaining sections each consist of separate parts; it is conceivable that both the sections and the parts can be played in different order as in Concretion, but that is not clear from the extant materials. As in Koellreutter's remaining works from the 1960s, the other sections consist mostly of sustained sonorities and often similarly extended silences. ‘Sunyata’ derives from the Sanskrit word for ‘emptiness’ and is a fundamental concept in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism; again, the word appears only on some manuscripts, not others, so it is not clear whether it was meant to serve as part of the title, although the work has usually been called this.

If, in Composition 68, Koellreutter dipped his toe into composition with non-Western materials and instruments (the tambura normally only plays sustained drones), Advaita (1970?) for sitar and ensemble, represents a more far-reaching engagement, and the sketches and manuscripts suggest that Koellreutter made wider use of original material, but the proliferation of potentially conflicting documents makes it impossible to gauge the nature and identity of the composition.

Koellreutter was similarly active as a performer and organizer, setting up the New Delhi String Orchestra and conducting the New Delhi Symphony Orchestra and Bombay Symphony Orchestra. Kater credits him with the first Indian performances of many canonic works, including Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. This could not be verified. Given the low level of familiarity with Western music in India at the time (and, to an extent, still today), contemporary music had to take a backseat. Koellreutter managed to smuggle in the odd composition by Schoenberg among more popular fare, and there was also an ‘Evening of Contemporary Music’ in 1968, at which Hindemith's Flute Sonata (with Koellreutter himself on the flute), Schoenberg's George-Lieder Op. 15 (featuring Schack) and Mauricio Kagel's electronic Transición I were performed.Footnote 97 Overall, the sheer number of materials held at the KF for this period paints a picture of restless activity.

Move to Japan

In 1969, Koellreutter was moved on to Tokyo to direct the GI that also covered South Korea. This was not his first encounter: as we have seen, he had been a visiting lecturer at Musashino College in 1953, and he returned in 1961 to attend the Tokyo and Osaka Festivals and pay another visit to the college. It was perhaps Koellreutter's most fruitful foreign posting, for Japan not only had an indigenous art music, but also a mature tradition in the performance and composition of Western music. He had already established contacts with leading avant-garde composers, and he would use his position to further and deepen these exchanges. One major occasion was the Japanese-German Festival of New Music. This had been established in 1967 by the composer Maki Ishii.Footnote 98 The holdings in the FK include the programme book from 1971, the fifth iteration. It was a lavish affair, with performances of works by nine German composers and groups, including Karlheinz Stockhausen, Mauricio Kagel, B. A. Zimmermann, Isang Yun (then, like Kagel, a naturalized German citizen) and Koellreutter himself and nineteen from Japan, among them Toru Takemitsu, Jo Kondo, and Toshi Ichiyanagi.Footnote 99 Koellreutter's own contribution was once again his Kulka-Gesänge. He also tried to set up another collaboration with the Darmstadt International Summer Courses, dubbed ‘Darmstadt in Japan’, which was meant to be held in Karuizawa, a popular holiday resort. The event was to be held in August 1971, and Koellreutter appears to have gained the cooperation of Aloys Kontarsky, a leading pianist specializing in new music, but it is not clear what happened to the plans.Footnote 100 It is also fair to say that, by that time, collaborating with or emulating the Darmstadt Summer Courses could no longer be considered forward-looking.

In Japan, too, Koellreutter took on teaching and performance opportunities, founding the Heinrich-Schütz Choir and teaching at the Christo Kyôkai Ongaku Gakkô (Japanese Christian Music Institute). In his compositions, he picked up where he left off in India. Yu or Yugen (1970) is composed for Japanese traditional instruments and soprano and sets four haikai by Matsuo Bashô. Like earlier compositions, it is subdivided into two major parts, which are in turn divided into three sections. According to the composer, the composition is supposed to follow the basic structure of a haiku, the number of syllables per line – 5/7/5 – but multiplies these by three: 15/21/15, representing the number of events per section.Footnote 101 I was not able to verify these claims. The work consists of two parts (I and II) with subsections A, B, and C; these are in turn subdivided into shorter passages (possibly what Koellreutter calls Gestalten). The division into two main parts is difficult to reconcile with the haiku structure; the subsections A, B, and C are more promising in this respect, but they recur and the specific proportions are not apparent.Footnote 102

That said, Yu represents a remarkable blend of Japanese and Western modernist elements. Although the compositional technique with its basis in serialism is clearly Western, Koellreutter's aesthetic at the time, with its ascetic reduction – itself indebted to gagaku – appears congenial to the instruments, resulting in a coherent and organic sound world (Example 8).Footnote 103 Yu was premiered, recorded, and subsequently toured by Ensemble Nipponia (later Ensemble Pro Musica Nipponia), which specialized in modernist compositions for traditional Japanese instruments. It was founded in 1964 by Minoru Miki,Footnote 104 who determinedly pursued this agenda and who also taught Koellreutter about Japanese music.Footnote 105 At its premiere, Yu was the only piece by a non-Japanese composer on the programme, and Koellreutter contributed an opening message (Grußwort) to the programme book, in which he outlined his aesthetic beliefs:

The emergence of a world culture is an imperative of the technological world. … But such a world culture presupposes a transformation of social forms … Therefore, as a consequence and reflex of this sociological transformation, a music will emerge of which we do not yet know what qualities will characterise it. It is impossible to predict whether the emerging world culture and the breaking down of national and racial barriers will lead to a greater intermingling of races and cultures, or to a concentration on familiar cultural values of the national tradition.

For this reason, I believe: as a result of a worldwide economic-social transformation a music will emerge which will be an expression of universal, objective thinking, but which will at the same time integrate the traditional values of earlier cultures.Footnote 106

Also in Japan, Koellreutter's compositions underwent another change: the introduction of graphic notation. As outlined, elements of open form, uncertainty, and approximation had been an important feature of Koellreutter's ‘planimetric’ compositions since Concretion, but it was based on staff notation. The first examples of graphic notation are in a series of compositions called Tanka (a Japanese short lyric genre), of which there are seven pieces covering the period from 1971 to 1982 (long after Koellreutter's return from Japan). The first three (No. 1 for koto and voice; No. 2 for piano, voice, tam-tam or low gong; and No. 3 for harp and spoken voice) – are notated graphically, while the remaining items use variants of conventional staff notation. The graphic notations use a variety of symbols but are largely based on indexicality. In other words, musical events are represented in a two-dimensional space, where the x-axis represents time and the y-axis pitch. Both are relative, however, and no absolute values are given. Furthermore, dots represent short and lines sustained notes and so forth. In this way, Koellreutter's procedures are in line with many others around the time. Amadio points out that he had copies of Erhard Karkoschka's primer on notation and Bogusław Schäffer's Introduction to Composition (although only the latter shows up in the FK's catalogue).Footnote 107 In addition, he was generally very well informed about recent developments. The rationale was provided by what Koellreutter called the ‘relativistic aesthetic of the imprecise and paradoxical’ (estética relativista do impreciso e paradoxal), in which he aligned artistic developments with science, technology, and intellectual history. This, too, was not uncommon at the time, if we consider Stockhausen and his indebtedness to Marshall McLuhan, for instance.Footnote 108 In Mu-Dai (1972) for solo voice, a setting of texts by Picasso, Koellreutter emulates John Cage's Aria by depicting relative pitch as a curvy line. In addition, numbers signify durations, derived from serial calculations, as the composer explains in his commentary.

Example 8. Koellreutter, Yu, beginning, Fundação Koellreutter.

The correspondence with Satoshi Tanaka

Around this time, 1974–6, Koellreutter entered into correspondence with Satoshi Tanaka, a professor of German at Meisei University in Tokyo. It is not clear how the two met, although Koellreutter's day job as director of the GI is the most likely explanation. The series of twelve letters (six by each correspondent) was subsequently published in Brazil (in Portuguese translation) and Japan (in the German original) and allows insight into a fascinating if problematic attempt at intercultural debate. It would appear as if the entire body was written with a view to publication: Tanaka opens his first letter, which started the exchange, in medias res without any introduction, and all letters are characterized by a formal style and exalted intellectual content, devoid of any personal matters. In addition, the letters are numbered, which is unique in Koellreutter's correspondence. Indeed, there are later letters between the two not included in the published version, which are dominated by personal matters and written in a more cordial and informal mode.

In the opening salvo, Tanaka refers to hearing Koellreutter's ‘Yume no naka no hito’ for recitation and koto and congratulates him on keeping his own identity and individuality without ‘Japanization’, despite the perceptible influence of Japanese artistic sensibility and aesthetics.Footnote 109 In response, Koellreutter confirms that he never intended to imitate Japanese music, but that he experienced his encounter with gagaku in 1953 as a validation of aesthetic ideals that he had always held and which he names as ‘extreme concentration of expression, economy of means, renunciation of sensuality, clarity and precision, independence from a rationally governed concept of time, asymmetry, an open, variable form, and other things’. Above all, though, he emphasizes that sound should not be an end in itself but instead a counterpart to silence. While this opening promises a fruitful exchange about the nature of cross-cultural encounter in music, the bulk of the exchange consists of a collision between diametrically opposed positions. Whereas Koellreutter took an uncompromisingly universalist stance, along the lines of his comments for the programme book for Ensemble Nipponia, Tanaka revealed a blatantly essentialist position, insisting on the irreconcilable differences between Japanese and, variously, German or, more widely European and Christian civilization – indeed, although he acknowledges the embeddedness of German culture in the European and Christian traditions, he is keen to differentiate Japan even from its neighbours, including China. This is not despite but because of the historical debt of Japanese culture from its larger neighbour: according to Tanaka, the Japanese are innately given to imitation and complete assimilation, so the only way of preserving a distinct identity is through hermetic isolation. As a result, he is critical even of the Meiji reforms and regards the widespread Westernization of Japan following WWII as disastrous, describing the present as ‘chaotic’, whereas he viewed the Tokugawa Shogunate (the Edo period of isolation from 1603 to the Imperial Restoration in 1868) as a golden age in which there were no differences and oppositions and everybody ‘perceived in the same way’ (gleichempfindend) – a perspective that seems to systematically exclude women and the lower classes, among others.

The only area of agreement between the two is the observation that Japanese culture is characterized by the principle of ‘as well as’ whereas Western culture emphasizes ‘either…or’, although Koellreutter points out that the former exists within Western culture too. Otherwise, both drift further apart and double down on their respective position, instead of trying to find common ground. The correspondence culminates in the following exchange, with Koellreutter stating in the fifth letter:

Eastern and Western culture too are not opposites, as many believe, but cultures that complement and complete each other. …

If one day it is realised that different cultures and civilisations are not opposites but correspondences – what is opposite either cancels out or complements each other – we stand on the threshold of a new world: namely, a world without opposites.

To which Tanaka responds in his sixth and final missive:

The more thoroughly I study art, the clearer the difference between East and West becomes to me. … I think it is time that we Japanese become aware of the distance that lies between our culture and that of other peoples. To this end, we should first and foremost study our own culture. Only when we do that will it be possible for us to come to terms with foreign cultural values.

In my opinion, dear Mr Koellreutter, we Japanese should now stand still, pause, reflect on our standpoint in the world, so that we can clearly recognise the difference between us and our opposites.

Despite some rhetorical brilliance and an impressive grasp of both German and Japanese cultural history, it is a fairly sterile exchange between inflexible and antagonistic positions. Tanaka's essentialism can only be described as reactionary. On the other hand, Koellreutter's lofty and utopian universalism appears hardly more reflected, and he never quite explains how individual cultures would fare under the unified global culture he envisaged. In other words, he seems incapable of conceiving of diversity at all, let alone as a positive value. Furthermore, there is no recognition of power imbalances, whether in terms of geopolitical history, as under colonialism, or in then-contemporary economic relations. On the contrary, although Koellreutter recognizes the process of economic and technological globalization, he appears to view this as somehow natural and neutral, not as something that is driven by powerful interested parties for their own benefit and often to the detriment of less powerful others.