The Cooperative Extension System (CES) land-grant mission is “to achieve the public good through higher education and to more fully realize benefits for society” (APLU Task Force on the New Engagement Planning Team, 2016). To fulfill this mission, CES broadly aims to democratize knowledge, integrate with and expand community partnerships, and advance the translation of research into evidence-based practice to benefit residents of the states. The research that is translated and the focus of programming have evolved over time, from Extension’s initial emphasis on innovative farming practices to today’s inclusion of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) in youth-based programming, and leadership in innovation to improve community health (e.g., Gould et al., Reference Gould, Steele and Woodrum2014). This chapter focuses on an area of programming that has not always been at the forefront of Extension efforts but that is gaining increased interest – supporting health and well-being in early childhood.

In this chapter, we will discuss the various approaches, theoretical models, and issues addressed by Extension in early childhood programming. Many of the programs focus on families, which are critically important for supporting young children’s optimal development. It is important to note that families can be thought of as units that have many different compositions. According to Learning for Justice (n.d.), a family is “a group of people going through the world together, often adults and the children they care for.” Families are diverse and include single-parent, adoptive, and foster families. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals may be raising one or more children as parents. Children may be living with grandparents, extended family members, or splitting time among different family members. Thus, in this chapter, we will use the term “family” to mean a single adult or group of adults caring for a child. We will use the terms “parent” and “caregiver” to indicate an adult with legal responsibility for the child, with the understanding that this may or may not be an individual who is the direct biological parent. One vitally important way to support families is for communities to support the provision of high-quality early childhood experiences for all children.

5.1 Evidence for Quality of Early Experiences: A Bioecological Framework

Early childhood is a critical period of lifespan development and can be understood using Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological framework. The framework recognizes the bidirectional associations among children’s early health and development and the contextual experiences that either enhance or impede it over time (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner2005; Swick & Williams, Reference Swick and Williams2006). The framework highlights community systems, which include cultural values, institutional structures, interactions among and between families and other systems; the family system itself, and individuals all interact to influence child and family well-being. The ecological feature of this framework, with its emphasis on proximal processes, suggests that the experiences children have with their primary caregivers during the first few years of life have the potential to create rich opportunities for early skill development, but that children are not passive recipients of influence in the process (Huston & Bentley, Reference Huston and Bentley2010). For example, when parents and caregivers talk to and read with young children, pointing to the pictures in the book and naming the objects, the child is learning about concepts, vocabulary, and how to respond to the caregiver. The child’s responses encourage the adult to continue the interaction. The increase in language input and positive feedback creates a cascade of neuronal development and faster neural networks in the brain that drive cognitive development (Romeo et al., Reference Romeo, Segaran, Leonard, Robinson, West, Mackey and Gabrieli2018).

Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological framework also draws attention to the environments in which child and caregiver interactions occur. Families’ and caregivers’ abilities to provide the type of support that promotes optimal child development are often dependent on caregivers’ knowledge and education, as well as the norms and expectations within the community where they reside. Factors that exist within the caregivers’ most proximal environments, such as having differential access to health care, education, parenting knowledge, and information can impact a child’s well-being (Rowe, Reference Rowe2017). Communities vary in accessibility of resources and programming including the amount and visibility of educational resources, availability of books, and occupational opportunities (Neumann et al., Reference Neumann, Hood, Ford and Neumann2012).

Adults are more likely to provide the type of environment and experiences needed to support optimal child development when they have more knowledge on how children grow and develop (Leung & Suskind, Reference Leung and Suskind2020). Children living in communities where there is ready access to learning opportunities and supportive social networks generally have more enriching environments and experiences. Conversely, when adults have less education, higher levels of stress, and less access to resources and support, they are less likely to provide enriching environments that optimize child development (e.g., see DeVoe et al., Reference DeVoe, Geller and Negussie2019). Therefore, ecological approaches that foreground individuals’ and communities’ needs, assets, and circumstances will create the kind of long-term impact necessary to support children’s well-being and positive development.

5.2 Child Well-Being

The Research Center for Childhood Well-being defines well-being as the quality of an individuals’ life, noting that “it is a dynamic state of living that is enhanced when people are able to fulfill their personal and social goals” (Statham & Chase, Reference Statham and Chase2010, p. 2). In a systematic review of child well-being studies, Pollard and Lee (Reference Pollard and Lee2003) identified five distinct domains therein, namely:

Physical well-being: Nutrition, physical activity, personal body care, immunizations, and safety-related behaviors;

Psychological well-being: Emotions, attachment, coping skills, resilience, and mental health;

Cognitive well-being: Intellectual, school attendance, and educational experiences;

Social well-being: Family relationships, quality of life, peer and other relationships; and

Economic well-being: financial aspects and support for daily living needs (e.g., food security).

Child well-being must also be considered in the context of family well-being, regardless of the family structure. In addition to the five elements identified, family factors such as caregiver education levels, stress levels, and the relationship stability of adults can also impact child well-being (Moeller et al., Reference Moeller, McKillip, Wienk and Cutler2016). Programs that will be described later focus on the broader family.

5.3 The Role of Extension as a System of Support and Influence

The CES has a history of delivering programming designed to positively impact participants’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors. Extension professionals disseminate information to clientele through both research and various practitioner outlets, as well as direct programming (Burkhart-Kriesel et al., Reference Burkhart-Kriesel, Weigle and Hawkins2019). One strength of Extension is its collaborative approach, particularly in establishing long-term partnerships with community organizations to address issues. Well-established partnerships allow for rapid responses to community needs and sustained efforts. When a crisis or natural disaster occurs, Extension can serve a critically important need by providing evidence-informed programming. For example, the Read for Resilience program at the University of Nebraska provided storybook guides and recommended children’s books to support young children’s coping and understanding of emotions in the aftermath of the blizzards and floods that rampaged the central regions of the state in 2019. As part of these efforts, Extension professionals also engage in translational research by evaluating their efforts to ensure that programs are relevant to the needs of the community and achieving targeted outcomes (see Monk, this volume).

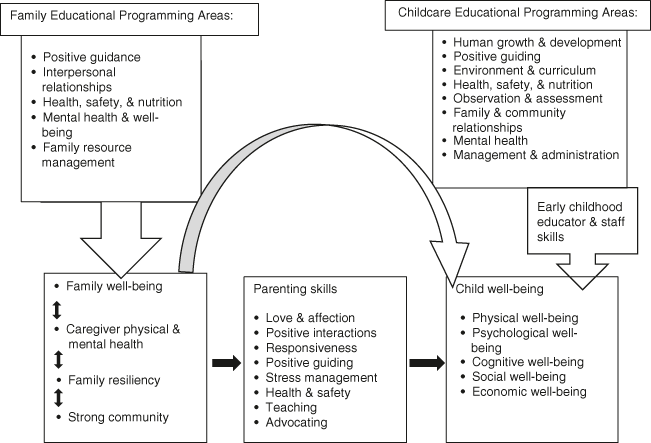

Figure 5.1 is a depiction of a holistic approach to Extension programming focused on the young child’s well-being. This diagram highlights how child well-being can be supported by programs that increase capacity among childcare providers and educators, as well as by efforts that foster family well-being. For example, Extension programs designed to bolster adult relationships, financial stability, and health and nutrition indirectly support a healthy family environment, which in turn supports child development. Figure 5.1 also summarizes the connections among Extension programming for adults, family well-being, parenting, childcare provider/teacher education, and child well-being.

Figure 5.1 Holistic model of the Cooperative Extension System support for child well-being.

Indeed, Extension systems in many states take a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to addressing complex problems that directly or indirectly impact children’s well-being. For example, Colorado State University’s multifaceted family enrichment program taught families strategies designed to support healthy relationships, parenting, and financial literacy. Evaluation of this program indicated positive participant outcomes in measures of positive family functioning, parenting alliance, and relationship satisfaction (Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Rosa, Henry and Benavente2014). These findings highlight the effectiveness of delivering education on the full range of parenting that in turn impact the quality of parent–child relationships and family functioning, and ultimately improve child well-being. In Section 5.4, we provide examples of programs targeting well-being in early childhood, recognizing that other types of Extension programming also have positive impacts on this population. We will also identify some themes that cut across programming approaches and propose suggestions for future research and program considerations.

5.4 Extension Early Childhood Programming

Within the field of early childhood, Extension provides a variety of programs that directly target young children, families, and early childhood educators. We will give examples that illustrate the responsiveness of Extension personnel to community needs in four main areas: parenting education, early childhood education, health and nutrition education, and emergent and evolving trends in early childhood. The programming in each of these areas focuses on a wide range of topics that include school readiness, childhood obesity, and mindfulness; and which help educators gain knowledge and skills to support children’s socio-cognitive, physical, language, and social-emotional development.

5.4.1 Areas of Early Childhood Extension Programming

5.4.1.1 Parenting Education

Parenting young children is an important and challenging responsibility. “Parenting” here includes the multiple roles and identities of adults who are caring for children. Although all parents and caregivers need knowledge and skills in effectively meeting the developmental needs of young children, many do not receive the information they need and may feel ill-equipped to be effective parents and caregivers. Families often struggle with children’s challenging behaviors. They may not know how to identify effective and developmentally appropriate ways to enhance young children’s growth and development. As a result, some parents need support in establishing realistic expectations of what children can and cannot do. Parenting education can help families and caregivers feel more confident in their skills and abilities to provide positive guidance and build healthy relationships with young children.

The National Association for Education of the Young Child (2019) defines “developmentally appropriate practice” as methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approach to joyful, engaged learning.

Parenting education programs are diverse and sometimes focus on specific age groups of children, such as the preschool or teenage years. Parenting education programs can also target specific audiences such as divorced parents, grandparents, foster parents, or families that have experienced domestic violence. One common factor among most of Extension’s parenting education programs is that they provide access to research-based information, often through educational classes. Teaching positive parenting skills to improve parents’ knowledge, coping, and problem-solving skills has been shown to promote positive long-term outcomes for children (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein, Lerner, Jacobs and Wertlieb2003). When caregivers develop warm and responsive relationships with young children, they reduce the long-term negative effects of poverty, stress, and trauma that children may experience (Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center, 2021). Additionally, parental knowledge of child development is a contributing factor in the increase of positive interactions between adults and children (Leung & Suskind, Reference Leung and Suskind2020). These studies, as well as many others, demonstrate the importance of parenting education in positively influencing child well-being. The following are examples of programs offered within Extension across the United States.

Just in Time Parenting, National Network of Extension Specialists (JITP). JITP is an electronically delivered age-paced parenting newsletter developed by a national network of Extension Specialists from twenty-four land-grant universities. JITP is designed to reach parents at teachable, transitional moments with research-based information about pregnancy, parenting, and child development from prenatal to five years old. Newsletters are designed to provide families with relevant information in a timely manner and are available in English and Spanish. Over 50,000 website users from all fifty states view the JITP website each year with over 13,000 families subscribing to the newsletter. Evaluations of the effectiveness of these parenting newsletters have shown that they increase parents’ knowledge of child development, their parenting self-confidence, and their ability to be nurturing and engage in positive parenting behaviors (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Bowers, Martin, Ebata, Lindsey, Nelson and Ontai2015). (Contact: Anne Clarkson, [email protected], https://jitp.info)

Building Early Emotional Skills (BEES), Michigan State University Extension. BEES is a series of classes for parents and caregivers of children ages zero to three years. It was designed to help audiences support children’s social and emotional development. The curriculum focuses on four main goals: (1) building parental awareness of emotions in self and child; (2) listening and interacting sensitively with the child; (3) identifying and labeling emotions; and (4) intentionally supporting early self-regulation skills. Over the course of eight units, participants learn about temperaments and how these traits can impact behavior. They learn strategies for strengthening their child’s social emotional development as well as how to manage stress and conflict within their families. The program is available in multiple format options including in-person, synchronous live webinars, and as an asynchronous cohort-based online course. A recent study of the program including delivery online or face‐to‐face platforms (N = 264 female caregivers; n = 214 online, n = 50 face‐to‐face) showed significant increases in knowledge, acceptance of negative emotions, and self‐reported emotionally supportive responses to emotions. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in rejection of emotions, emotionally unsupportive responses, and parenting distress. Results suggested no differences in rate of change by program delivery type (Brophy-Herb et al., Reference Brophy‐Herb, Moyses, Shrier, Rymanowicz, Pilkenton, Dalimonte‐Merckling and Mitchell2021). (Contact: Kendra Moyes, [email protected])

Sustainable Community Project to Promote Early Language and Literacy Development in Native Communities, University of Arizona Extension. This comprehensive, community-based, and sustainable program is designed to promote early literacy in two American Indian communities in Arizona: the Nahata Dziil, Wide Ruins, Pine Springs, and Houck Chapters of the Navajo Nation and the communities on the San Carlos Apache Tribal Lands. The program was developed in collaboration with community stakeholders and in partnership with two community advisory boards to ensure that programming addressed community-identified needs and was culturally responsive. Programming targets a wide and inclusive range of caregivers including parents and other guardians; grandparents; extended family and other caring adults; Head Start teachers; pre-K teachers; center- and home-based childcare providers; and family, friend, and neighbor care providers. The program includes both single-session and multi-session programing designed to encourage caregivers to increase their time reading with young children, to improve the quality of their book-reading practices, and to increase the use of non-book-reading activities that promote early literacy. For example, non-book-reading activities (e.g., singing and storytelling) are encouraged because Apache and Navajo families have strong oral storytelling traditions. An aim of the program is to enhance community capacity to sustain high-quality early literacy programming through professional development workshops for early care and education teachers and providers. (Contact: Katherine Speirs, [email protected])

Gay, 2002 defines culturally responsive practice as using the experiences, strengths, and perspectives of children and their families as a tool to support them more effectively.

Magic Years, Cornell Cooperative Extension. Decades of research shows that children are affected by who their parents are, what their parents know, what their parents believe, what their parents value, what their parents expect of them, and what their parents do (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2009). Based on these findings, the Magic Years lessons are designed to provide Extension educators with tools and resources to explain best practices in child development and parenting to caregivers. The program targets families with children from birth to age four who want to enhance their parenting skills and aims to benefit the whole family. Classes assist participants in developing a deeper understanding of how their self-knowledge, parenting knowledge, and behavior affect their children. Participants have included military families, Head Start families, and families referred through the Department of Social Services Child Protective Services program. Program leaders reported the results of a pre/post survey from participants (n = 48). They found significant increases in six out of ten indicators of parenting knowledge and belief. Specifically, participants reported increased confidence in making rules which take their child’s needs into consideration, increased time spent reading with their child, increased feelings of support, increased self-efficacy in the skills necessary to be a good caregiver, increases in how often they praise their child, and increased use of explanations for the rules they make (Korjenevitch, Dunifon, & Kopko, Reference Korjenevitch, Dunifon and Kopko2010). (Contact: Amanda Rae Root, [email protected])

The programs highlighted thus far are examples of Extension education targeted at increasing parents’ and caregivers’ knowledge of child development, with emphasis on cognitive and social-emotional development. Next, we will look at programming focused on children’s health and physical development.

5.4.1.2 Health and Nutrition Education

Extension health and nutrition programming is designed to improve the physical health of community members through healthy food choices and physical activity. One of the most well-known examples of initiatives with broad reach in this area is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – Education (SNAP-Ed, see Franzen-Castle, this volume). SNAP-Ed targets individuals using or eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and is designed to help participants increase their knowledge about healthy eating habits, how to make their food dollars stretch further, and strategies for increasing physical activity. In addition to SNAP-Ed, numerous Extension programs are developed and delivered in partnership with community organizations as they collaborate to teach nutrition education classes, employ social marketing campaigns, and work to improve the policies, systems, and environment of their communities. Below are some examples, along with contact information of key leaders.

Little Book and Little Cooks, University of Nevada, Reno Extension. Little Books and Little Cooks (SNAP-Ed funded) is a seven-week parenting education program for preschool-age children (three–five years old) and their parents designed to promote healthy eating, family literacy, parent–child interaction, and children’s school-readiness skills. During the program, children and parents come together to learn about healthy eating and nutrition, gain positive parent–child interaction skills, and practice school-readiness skills. Parents and children read children’s books about healthy eating and nutrition and have opportunities to cook and eat together. Each weekly session features a new book about healthy eating and a corresponding recipe. Researchers use a pre/post evaluation consisting of parent reports and an observation checklist to assess impact. Results indicate that parents view the program positively, and that there are significant increases in target behaviors including positive parent/child interactions, children and parents trying new foods, and consumption of fruits and vegetables (Kim, Reference Kim2016). (Contact: YaeBin Kim, [email protected])

The Kids Coupon Program – West Virginia University Extension. The Kids Coupon (or Kids Farmers Market) program gives children from low-income households $4 in tokens with which to purchase fresh, local fruits and vegetables from a market that is brought to childcare centers, schools, and community locations. Children and families also participate in nutrition education and food sampling. The program is organized and operated through SNAP-Ed and tokens are funded by private donors. The program has provided over 5,400 children across the state of West Virginia with vouchers. The overall objective of the program is to encourage young children to try new fruits and vegetables by giving them the buying power to make their own choices. Program directors have used parent-report surveys to evaluate impact. Results are promising, with 91 percent of parents reporting that their children ate the produce they purchased and that those children increased their knowledge about fruits and vegetables (McCartney et al., Reference McCartney, Wood, Gabbert and Poffenbarger2019). (Contact: Kristin McCartney, [email protected])

iGrow Readers, South Dakota State University Extension. iGrow Readers is a series of six book-based lessons focused on helping children (pre-K to 3rd grade) understand the benefits of making healthy decisions involving nutrition and physical activity. In groups, children read books that reflect the themes of the program and then participate in nutrition and physical activities that reinforces the concepts covered in the readings. Companion parent newsletters encourage reading and healthy lifestyles at home. The program is designed for limited-resource audiences served through the SNAP-Ed and Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) and reaches approximately 4,000 young children each year. An initial evaluation using a pre/post survey with children and a feedback survey collected from teachers found a significant increase in knowledge of nutrition and physical activity for participants (Loes et al., Reference Loes, Huber, Bowne, Stluka, Wells, Nelson and Meendering2015). (Contact: Kimberly Cripps, [email protected])

My TIME to Eat Healthy and Move More, University of Minnesota Extension. My TIME to Eat Healthy and Move More is a home-based program for parents or caregivers (e.g., grandparents, home-based early childhood providers) and their children ages three to five years. This unique program actively engages parents and children in a co-learning process as they experience making healthy food choices and becoming more physically active. By participating in this home-based program, parents and children learn about the importance of varying foods and physical activity for better health. Families have opportunities to prepare and eat healthy recipes and participate in physical activity while learning about the importance of daily exercise as a part of good health. Families also learn and practice ways to save money on groceries. The program consists of twenty-four 15-to-20-minute mini-lessons clustered into six units. Lessons occur in the family’s home and mix instruction and activities, including games, exercise, reading, and tasting demonstrations. Although no published evaluation information is available, the program’s directors report 340 families participated in a pilot evaluation. They report that children then consumed more fruits and vegetables, and families increased both their physical activity and their understanding of healthy eating (Caskey et al., Reference Caskey, Kunkel, Krentz and Schroeder2018). (Contact: Mary Krentz, [email protected])

5.4.2 Early Childhood Education

Early childhood educators play a key role in young children’s well-being. Sixty percent of children ages three to five years in the United States spend an average of thirty-six hours a week in center-based childcare (Mamedova & Redford, Reference Mamedova and Redford2019). Quality childcare is linked to children’s cognitive development and overall well-being, and as such opportunities for educators to expand their knowledge and skills relevant to early childhood care is critical (Donoghue, Reference Donoghue2017).

An environmental scan of early childhood professional development programs offered within the Extension system indicated that Extension played an essential role in providing professional development opportunities for early childhood professionals (Durden et al., Reference Durden, Mincemayor, Gerdes and Lodl2013). Extension personnel often collaborated with multiple organizations within their states. Various partners such as Child Care Resource and Referral agencies, Health and Human Services, Head Start and Early Head Start, the Department of Education, Offices of Early Learning and Development, and the National Association for the Education of Young Children are engaged in working with Extension staff to support and enhance the quality of early childhood services. Extension personnel provided early childhood educators with a variety of training classes and online resources. Below are examples of programs and resources offered by Extension on the topic of early childhood education.

Better Kid Care, Penn State Extension. Penn State’s Better Kid Care (BKC) has been providing online, evidence-informed professional development via its customized learning management system, OnDemand, since July 2011. Prior to 2011, BKC reached clientele through postal mail. Better Kid Care offers educational programming in a wide variety of topics including child growth and development; curriculum and learning experiences, health, safety, and nutrition; and organization and administration. The OnDemand system currently has 317 courses. Better Kid Care serves learners from all fifty states and more than sixty countries. Since 2011, more than 600,000 professionals have completed more than 2,370,000 courses, which equals approximately six million professional development hours. One study evaluating the impact of BKC indicated promising results. In in-depth interviews, most participants (79 percent) described specific, useful knowledge or skills (e.g., behavior management, communication with parents, environments for learning, and safety) they had gained from the programs. Eighty-five percent of respondents also described specific improvements they had made in their early care and education programs as a result of BKC (Ostergren et al., Reference Ostergren, Riley and Wehmeier2011). (Contact: Jill Cox, [email protected])

Infant Toddler Child Development Associate (CDA) Training and Coaching Program, University of Nevada, Reno Extension. The Infant Toddler CDA Training and Coaching Program is designed to improve the care and education of infants and toddlers. The program also increases career advancement opportunities for teachers completing the program and receiving the CDA credential from the national Council for Professional Development. The grant-funded program provides 120 hours of coursework across eight specific content areas through training and online modules, and bi-monthly coaching sessions with a knowledgeable, experienced coach to practice skills and discuss challenges. To earn the full credential, participants must also complete 480 hours of work in an infant/toddler classroom, assemble a professional portfolio, distribute and collect parent questionnaires from a majority of the families in their classroom, pass a comprehensive exam, and undergo teaching observation by a Child Development Associate Professional Development Specialist.

To determine the impact of the program, the CLASS (Classroom Assessment Scoring System), an observation instrument, has been used to assess the quality of teacher–child interactions. Findings suggest positive and significant gains in responsive caring among providers in infant classrooms between pre- and post-tests, and positive and significant gains in emotional and behavioral support and engaged support for learning among educators in the toddler classrooms. Teachers participating in the program reported that their teaching practices were strengthened, and that they had gained the skills and tools needed to be more confident and intentional teachers. (Contact: Teresa A. Byington, [email protected])

Early Care and Education Projects, University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service. Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service facilitates four, grant-funded childcare provider training programs that are free to the public. These training programs include Best Care, which is ten hours of face-to-face training created by state faculty and staff and facilitated by county extension agents who train around 2,400 childcare providers, foster parents, and teachers annually. Best Care Connected and Best Care Out-of-School-Time are each five hours online, created by state faculty and staff and presented in five one-hour modules. These programs target teachers and childcare providers. The Guiding Children Successfully program provides 2,000 participants with up to thirty-eight hours of online or correspondence training. The correspondence training is especially helpful for participants who live in areas with limited Internet access or who do not have access to computers or are uncomfortable using them. Approximately 6,000 childcare providers participate in these programs each year. (Contact: Brittany Schrick, [email protected])

Passport to Early Childhood Education and Essentials Child Care Preservice, Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. Iowa State University Extension offers many different programs for early childhood professionals. These programs include the Passport to ECE Program Administrators course that provides online instruction in the observation of teaching practice, giving effective feedback, and supporting ongoing professional development. The three-week (six-hour) online course uses quick video mini-lessons that easily fit within busy schedules and include chat discussions with other program administrators. The curriculum is accessible by computer, tablet, or smartphone. The Passport to Early Childhood Education for Teachers and Staff online course introduces the basic skills and knowledge to teach and care for children in center-based programs. Teachers quickly learn through video lessons how to create support for early learning and build positive relationships. This eleven-hour online, self-paced curriculum is free, available 24/7, can be implemented immediately, and is designed to easily fit within early childhood professional’s busy schedules.

The Essentials Child Care Preservice course is composed of twelve online sessions and must be completed by all beginning childcare providers in the state of Iowa. The course provides helpful answers to many questions about creating a safe and healthy early childhood environment, preparing for an emergency, transporting children, preventing and controlling infectious diseases, handling and storing hazardous materials, giving medication, managing food allergies, creating a safe sleep environment for infants, preventing shaken baby syndrome, understanding child development, supporting cultural diversity, and understanding homelessness. Over 11,000 early childhood professionals complete this course each year. (Contact: Lesia Oesterreich, [email protected])

5.4.3 Recent and Evolving Trends in Early Childhood

Several new topics relevant to early childhood well-being are emerging within Extension. Examples of emerging issues include an increasing awareness of the need to address mental health and well-being among early childhood caregivers and educators, the use of technology in innovative ways to reach new audiences and provide valuable information to families, and the need for programming to address equity, diversity, and inclusion. The world continues to change and evolve. As such, it is critical that Extension professionals are open and responsive to addressing emerging issues that affect the well-being of young children. Below are examples of recently emergent programming.

5.4.3.1 Mindfulness Education

There is increasing evidence that mindfulness and reflective practices are promising and practical ways to prevent and reduce the stress of early childhood teachers. Saltzman (Reference Saltzman2011) defines mindfulness as paying attention to your life, here and now, with kindness and curiosity. Because of the resulting lower levels of depression and workplace stress, early childhood teachers who formally practice mindfulness may experience higher quality relationships with children in the classroom (Becker et al., 2017).

Cultivating Healthy Intentional Mindful Educators (CHIME), Nebraska Extension. CHIME is a program designed to provide education and guidance on how to incorporate mindfulness, self-compassion, and reflective practice into the daily routines, teaching, and caregiving to foster healthy and adaptive emotion regulation skills among early childhood (Hatton-Bowers et al., Reference Hatton-Bowers, Clark, Parra, Calvi, Bird, Avari, Foged and Smith2022). Engaging in mindfulness and reflective practice has many benefits for health and well-being of both early childhood professionals and young children, including reduced stress, improved emotion management, better sleep quality, increased focus and attention, and enhanced relationships. CHIME program consists of a two-hour introduction followed by seven weekly CHIME sessions on topics that include mindfulness in breathing, listening, emotions, speech, gratitude, and compassion. CHIME aims to support early childhood educators in enhancing and improving their well-being so they can be more effective as caregivers. The program helps to facilitate each participant’s thinking to become present in one’s personal and professional life, and to find the space to care for children with more calm and sensitivity, even during difficult and stressful moments. (Contact: Holly Hatton, [email protected])

5.4.3.2 Innovations with Technology

The CES has historically been a leader in using innovations to improve community health outcomes. Extension professionals have used a broad range of strategies, including using technology in innovative ways to support their work in early childhood. Using social media platforms, new content delivery vehicles, and innovative measurement, Extension professionals constantly strive to reach their audiences in a variety of ways. Technology is a powerful tool in the expansion of Extension programming. For example, in the Parenting: Behind the Behavior video series, educators from the University of Wisconsin-Madison/Extension Human Development and Relationship Institute (HDRI) have aired short, weekly Facebook videos about positive parent–child relationships. The goal of these videos is to reach a wide range of parents and caregivers to increase applicable parenting skills and build knowledge of Extension resources statewide. The series engages Extension specialists, faculty, and county educators, each speaking in short three-to-five-minute videos about specific parenting and child interaction skills. Topics range from emotion coaching to outdoor play and talking to children about racism. Many of the viewers have indicated this was their first exposure to Extension programming.

Another example of using new methods of delivery is the Science of Parenting (SOP) podcast that was launched in 2019. Accessible in video and audio formats, the wide availability and rapid turnaround of podcasting allowed the team to add COVID-specific information to their line-up. An impact report from October of 2020 indicates listeners downloaded the podcast over 11,000 times, and the Facebook video podcast episodes reached approximately 30,000 views over the series of thirty episodes.

Technology can also be an innovative way to collect and use data to motivate participants to take up evidence-based strategies to support child development. A program at Iowa State University called Small Talk utilizes LENA Start™, a universal preventative intervention from the LENA® Research Foundation. The package includes the curriculum and access to a cloud-based program and data-management system (LENA® Online). This plug-and-play curriculum is designed to interactively teach caregivers how to talk to and read more with their children and why those activities are essential, and to provide participants with quantitative linguistic feedback (Suskind et al., Reference Suskind, Leffel, Hernandez, Sapolich, Suskind, Kirkham and Meehan2013) about their talk and conversation habits. During each week of the program, the participant places a wearable digital language processor on a child to complete a sixteen-hour recording of their talk and conversation with the focus on child. A cloud-based system processes the recordings. The following week, participants receive a printed report that details the number of adult words (AW) and the number of conversational turns (CT) with the target child. Additionally, the system includes automatic text messages that ask parents to report on the number of reading minutes for the week. The evaluation study used a quasi-experimental comparison design to examine the changes in talk relative to participants who regularly visit the library but did not participate in the program. Findings demonstrated statistically significant growth in weekly estimates in adult language input to children, conversational turn-taking, and child vocalizations for the intervention group but not for the comparison group (Beecher & Van Pay, Reference Beecher and Van Pay2020).

5.4.3.3 Increased Focus on Data and Evaluation

Researchers and evaluators have acknowledged that evaluation methods and tools used in Extension programs can benefit from improved sophistication and rigor (Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, Blake, Chazdon and Radhakrishna2015). In the published studies on Extension, most effectiveness studies reported evidence of outcomes beyond participation level. However, few studies include long-term outcomes or follow-ups (Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Rosa, Henry and Benavente2014). There is increasing recognition among scholars and practitioners that Extension would benefit from increasing efforts in a variety of outcome measures, including longitudinal studies that track long-term impact, and studies that can inform evidence-based practice (e.g., see Monk, this volume). Rigorous evidence is critical to effective demonstration the public value of early childhood Extension programming and communicating public value of Extension. Although such types of evaluation can be expensive and require significant commitment by Extension faculty, collaborations with other university partners, and incorporation of innovative technology may make such efforts more feasible.

5.4.3.4 Addressing Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

There is an ongoing need to create and offer programming that addresses issues related to equity, diversity, and inclusion. Rhian Evans Allvin, Chief Executive Officer of the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), stated that “children are best understood and supported in the context of family, culture, community, and society” and that “we must confront biases that create barriers and limit the potential of children, families, and early childhood professionals” (Allvin, Reference Allvin2018, n.p.). NAEYC (2019) has released a position statement on Advancing the Equity in Early Childhood Education that calls for inclusive teaching approaches and equitable access to learning environments within the field of early childhood. Everyone, including Extension personnel, is challenged to “seek information from families and communities about their social and cultural beliefs and practices” to inform the development of programming that is responsive to the audience it serves (NAEYC, 2019). Extension professionals are encouraged to work with “community leaders and public officials to address barriers” and create systems that support the diversity of the children and families served and to provide equitable access to all programming (NAEYC, 2019). Although Extension is engaging in programming and research that promotes childcare quality that is culturally responsive, there is a need for greater attention to reconceptualization of quality programming to include, identify, leverage, and support the rich cultural and linguistic backgrounds of diverse families (Souto-Manning et al., Reference Souto-Manning, Falk, López, Barros Cruz, Bradt, Cardwell and Rollins2019).

Implications for Extension professionals working in Early Childhood program areas. Extension personnel offering early childhood programming must examine their programming through a social equity lens, identify biases, and seek greater input from culturally diverse, underserved audiences. It is time to listen and learn more about meeting the unique needs of today’s families. Yesterday’s programming may no longer be relevant to the current issues faced by families that have endured a global pandemic, societal prejudices, and social unrest. Additionally, researchers have called for the effectiveness of family enrichment programs to be examined with populations with low resources, underserved populations, and culturally diverse communities (Johnson, Reference Johnson2012). In the United States, children from multiple races represent the fastest growing demographic group today (Vespa et al., Reference Vespa, Medina and Armstrong2020). When early childhood professionals and/or parent educators come from a cultural background different from that of the families or communities they serve, more training or information on the cultural implications is necessary to successfully engage with diverse families and communities (Timmons & Dworkin, Reference Timmons and Dworkin2020).

Extension professionals are charged with being nimble and seeking feedback from stakeholders and community members to determine how best to serve and educate today’s families. One way to strengthen cultural capital and engagement with diverse communities is to create ways to share or gather contributions to programs from these diverse audiences when designing programming, training, or curriculum, instead of trying to add surface-level diversity in the form of representation after programs have been created (Timmons & Dworkin, Reference Timmons and Dworkin2020).

One example of responsive programming is the Including All of Us program, which trains early childhood professionals on diversity, equity, and inclusion in early childhood. The program helps participants learn to understand individual and group identity and their own worldview, learn about antibias education and cultural competency, and develop strategies to collaborate with families to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion. The Including All of Us training is an intensive six-hour experience led by a cross-racial facilitation team. To promote sharing and full participation, training groups are limited to twenty-five participants. This training goes beyond merely receiving information by using self-reflection and group discussions to scaffold learning around diversity, equity, and inclusion. Twenty-two early childhood professionals participated in the pilot program. Program evaluation reported changes in knowledge and attitudes surrounding diversity, equity, and inclusion, including greater understanding about differences. Participants also indicated planned behavior changes, such as implementing antibias techniques and lessons. (Contacts: Kylie Rymanowicz, [email protected]; Vivian Washington, [email protected])

5.5 Conclusions and Recommendations

Fostering young children’s healthy development is critical to the development of future productive citizens and the vitality and health of communities. Supporting children’s health and well-being requires a collaborative effort to create the optimal environment for their development. The CES is well positioned to lead the way toward enhancing the well-being of children in the domains of physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and economic well-being; and has implemented numerous cutting-edge responses that engage numerous partners and a range of approaches. Despite the considerable contributions of the CES, there is more to be done. Extension personnel should continue to build new partnerships and address community needs by engaging in deep listening with diverse voices from underrepresented populations. Extension has had a long history of helping underrepresented populations build networks and gain social capital (see Do & Zoumenou, this volume). This can be beneficial in the building of partnerships but also can reinforce privileged identities and homogenous groups.

Social capital is a multilevel concept regarding the quality of personal relationships, such as personal and community networks, sense of belonging, and civic engagement. It includes social norms of reciprocity and trust, which impacts the quality of life, including well-being (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000).

Putnam (Reference Putnam2000) notes that social capital can be a critical component of social and psychological support to members of the in-group but can also negatively lead to antagonism toward out-group individuals. Extension should continue to look for ways to diversify the workforce and seek to engage and support the cultural capital of historically underserved and marginalized populations. The concept of helping families build their social capital is an interdisciplinary approach that could impact well-being in a broader scope. For instance, a recent study found many forms of family social capital were associated with reducing or negating the effects of childhood adversity when it was present at multiple ecological levels (Kysar-Moon, Reference Kysar-Moon2021). Relatedly, research and educational offerings that promote childcare and parenting quality with culturally responsive, sustained, and relevant pedagogy are scarce. This lack is particularly critical considering the recent emphasis on reconceptualizing high quality to be inclusive of historically underserved and marginalized teachers, children, and families (Souto-Manning et al., Reference Souto-Manning, Falk, López, Barros Cruz, Bradt, Cardwell and Rollins2019). Given Extensions’ vast network and long history of responding to community needs, the potential to be a leader in this highly needed work is an opportunity for Extension to team with community partners to promote the health, well-being, and quality of life for our communities and particularly the lives of young children.