In Western countries, high standards of living provide good conditions for health, formally irrespective of one’s social position. Despite these good theoretical conditions, there is an inverse gradient between socio-economic status (SES) and health. For example, in Germany, the estimated risk for diabetes mellitus type 2, heart disease or liver disease is twice as high for individuals with the lowest SES compared with individuals with the highest SES( Reference Lampert, Kroll and Lippe 1 ). Moreover, risk factors for common civilization diseases like physical inactivity and higher smoking prevalence, as well as less use of primary prevention services are more common in population groups with lower and lowest SES. This is also true for the risk factor high BMI( Reference Lampert, Kroll and Lippe 1 , Reference Weyers, Dragano and Richter 2 ). For example, the German Health Update 2012 for the German population aged between 18 and 79 years revealed that 31·4 % of women with the lowest SES were identified as overweight (BMI≥25·0 kg/m2) and another 23·6 % as obese (BMI≥30·0 kg/m2). But in women with the highest SES, the estimated overweight and obesity prevalence was much lower: 24·2 % of the women were overweight and another 9·4 % were obese( 3 ). For men, the findings are less clear. Nevertheless, obesity prevalence was also significantly higher in men with the lowest SES than in men with the highest SES (20·0 v. 14·1 % in the age group 18 to 79 years)( 3 ). Overweight and obesity carry high social and economic burden. For example, in Germany, direct costs of obesity were estimated as €29·39 billion and the indirect costs as €33·65 billion per year( Reference Effertz, Engel and Verheyen 4 ). Therefore, it is of utmost importance to identify the underlying links between SES and BMI, which might help to develop suitable prevention strategies against overweight and obesity.

One link between SES and BMI is eating behaviour, which differs between the SES groups. For example, higher consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is more common in the lower and lowest SES groups( Reference Malik, Schulze and Hu 5 , Reference Weyers, Fekete and Dragano 6 ). Regarding the various interacting factors which lead to one’s individual eating behaviour, including genetic, sociocultural and personal ones, there is no simple explanation for the differences in eating behaviour between SES groups. Therefore, we hypothesized that psychological factors of eating behaviour might be underlying factors between the inverse association of SES and BMI. Common and well-established psychological domains of eating behaviour are: (i) a domain which describes the degree of cognitive control in daily food intake (cognitive restrained, restrained eating); (ii) a domain which describes the loss of control over food intake (uncontrolled eating, disinhibition); and (iii) a domain which describes eating in response to emotional triggers like feeling anxious or depressed (emotional eating)( Reference Ganley 7 – Reference van Strien, Frijters and Bergers 13 ). The association between these psychological domains of eating behaviour and BMI are well studied. Especially the domains uncontrolled eating and emotional eating have been found to be associated with higher BMI values( Reference French, Epstein and Jeffery 14 – Reference Loffler, Luck and Then 17 ). As eating behaviour has not only been found to be associated with BMI, but also with SES, in the present study we particularly aimed at investigating potential pathways between SES and the psychological eating behaviour domains ‘restrained eating’, ‘uncontrolled eating’ and ‘emotional eating’ and the BMI in the adult population. To the very best of our knowledge, this has not been done before.

Methods

Ethics statement

All participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the study. The study complies with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig, Germany.

Participants

Data were derived from the large population-based LIFE-Adult-Study that was conducted by the LIFE–Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases in Leipzig, Germany (August 2011–November 2014). The LIFE-Adult-Study aims to examine the prevalence, early onset markers, genetic predisposition and the role of lifestyle factors in major civilization diseases such as obesity, diabetes and CVD. The study design of the LIFE-Adult-Study has been described in detail elsewhere( Reference Loeffler, Engel and Ahnert 18 ). An age- and sex-stratified sample of residents of the city of Leipzig, Germany, was randomly selected from lists provided by the Leipzig registry office. The response rate was 33 %. Eating behaviour was completely assessed in 6657 participants. We excluded participants whose eating behaviour might have been influenced by symptoms of chronic inflammatory bowel disease, treatment of cancer disease, insulin treatment or intake of antipsychotic drugs (n 722). The present analysis was based on a final sample of 5935 participants aged 18–79 years.

Data collection and assessment procedures

All participants underwent a comprehensive assessment programme including a variety of physical and medical examinations, clinical interviews and standardized questionnaires. The assessments were conducted by trained study personnel at the LIFE research centre located on the premises of the University Hospital of Leipzig. For the present report, data were analysed from the following assessments.

Eating behaviour

Eating behaviour was assessed with the Fragebogen zum Essverhalten (FEV), the German version of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ)( Reference Stunkard and Messick 8 , Reference Pudel and Westenhoefer 12 ). The present analysis was based on a revised twenty-nine-item version of the TFEQ, which covers three domains of eating behaviour: ‘uncontrolled eating’, ‘restrained eating’ and ‘emotional eating’. The internal consistency of the scales (Cronbach’s α) was stated as 0·802 for the domain of uncontrolled eating (contains fifteen items), 0·840 for the domain of restrained eating (contains eleven items) and 0·780 for the domain of emotional eating (contains three items)( Reference Loffler, Luck and Then 17 ).

As mentioned above, the domain of uncontrolled eating describes the tendency to lose control over food intake, the domain of restrained eating describes a permanent cognitive control of food intake order to lose or to control body weight, and the domain of emotional eating describes eating in response to emotional triggers like feeling anxious or depressed.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic information was obtained via a standardized interview, which included questions about the educational and occupational qualification of the participant, the net household income and actual occupational status. This information was used to assess the multidimensional SES-Index-Score in accordance with the approach used in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults( Reference Lampert, Kroll and Müters 19 ). The SES-Index-Score is based on the three domains of ‘education’, ‘work’ and ‘income’. For each participant of the LIFE-Adult-Study, each of the three domains was rated between 1 point as the lowest possible value and 7 points as the highest possible value. The points of the three domains were then added to a final score (range 3–21 points) and participants were categorized into one of the three SES groups: ‘low’ (3–8 points), ‘medium’ (9–14 points) or ‘high’ (15–21 points).

Anthropometry

Body weight was measured with an electronic scale (SECA 701, Seca GmbH & Co. KG) with a precision of 0·01 kg. Body height was assessed by means of a stadiometer (SECA 240) to the nearest 0·1 cm. BMI was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the squared height in metres (kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0, including the SPSS macro ‘PROCESS’ from Preacher and Hayes( Reference Preacher and Hayes 20 ). All analysis employed an α level of 0·05 for statistical significance (two-tailed). Group differences were analysed using Mann–Whitney U tests, χ 2 tests and Kruskal–Wallis tests as appropriate.

To examine the pathways between SES, BMI and the eating behaviour domains, we conducted mediation analysis. For our analyses, we hypothesized that the psychological domains of eating behaviour (uncontrolled eating, restrained eating, emotional eating) mediate the association between SES-Index-Score and BMI. Previous analysis required differences in eating behaviour between men and women. Therefore, we conducted sex-stratified analysis( Reference Löffler, Luck and Then 21 ). We also used age as covariate, as age was found to be an influencing factor on eating behaviour( Reference Löffler, Luck and Then 21 ).

To detect the presence of mediation effects, we first examined the associations between the obtained variables. Therefore, we conducted Pearson’s correlation analysis. Then we developed a parallel-mediation model to examine the potential direct, indirect and total effects of eating behaviour on the association between SES-Index-Score and BMI, controlled for covariates. Parallel mediation was used to simultaneously include the three eating behaviour domains in one model. A ‘direct effect’ describes the direct association between SES-Index-Score and BMI in the presence of the mediator(s). An ‘indirect effect’ describes the product of the paths between SES-Index-Score and BMI and between SES-Index-Score, the mediator(s) and BMI. The ‘total effect’ is the sum of the indirect and direct effect. Thus, a full mediation of the association between SES-Index-Score and BMI by eating behaviour would be present if there was an indirect effect via eating behaviour, but no direct effect of SES-Index-Score on BMI in the model. A partial mediation would be present if both the path between SES-Index-Score and BMI and the path between SES-Index-Score, eating behaviour and BMI was significant. To achieve scale similarity, we conducted a z-transformation of all included variables. A z-scale has an arithmetic mean of 0 and an sd of 1, and allows the interpretation of regression coefficients more easily. Significance of the direct and indirect effects was tested with both the Sobel z-test and a bootstrapping procedure of about 10 000 resamples. The bootstrap procedure providing 95 % CI is additionally recommended for significance testing as it respects irregularity of the sampling distribution and provides more power( Reference Preacher and Hayes 20 ).

Results

Sample description

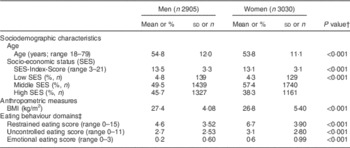

Overall, analysis of the association between SES, eating behaviour and BMI was based on a sample of 5935 participants of the LIFE-Adult-Study. Characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Main characteristics of and significance differences between the study sample of men and women (n 5935), LIFE-Adult-Study, Leipzig, Germany, August 2011–November 2014

† Group differences in continuous variables were analysed with the Mann–Whitney U test, group differences in categorical variables were analysed with the χ 2 test.

‡ Higher scores indicate stronger characteristic values in the domains.

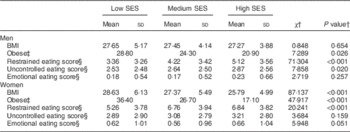

Table 2 presents a detailed overview on the association between the factors BMI and eating behaviour with SES. Group comparisons using Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed a higher mean BMI in lower SES groups, especially in women (χ 2 for men=0·848, P=0·654; χ 2 for women=87·137, P<0·001). Additional information about the proportion of obesity in SES classes is given. The proportion of obesity was higher in lower and lowest SES in both men and women compared with the highest SES group. Values of restrained eating were higher in the higher SES groups in both men and women (χ 2 for men=71·304, P<0·001; χ 2 for women=20·241, P<0·001). Values of uncontrolled eating and emotional eating did not differ between lowest and highest SES groups.

Table 2 Differences in BMI and eating behaviour scores according to socio-economic status (SES) for men and women (n 5935) aged 18–79 years, LIFE-Adult-Study, Leipzig, Germany, August 2011–November 2014

† Group differences were analysed with the Kruskal–Wallis H test.

‡ Proportion of obesity in %; obesity is classified as BMI≥30·0 kg/m2 ( 27 ).

§ Higher scores indicate stronger characteristic values in the domains.

Intercorrelation between SES-Index-Score, BMI, eating behaviour and the covariates

As shown in Table 3, we found weak (Pearson’s correlation coefficient r<0·3) but significant associations between SES-Index-Score and BMI for both men and women. We also found weak associations between SES-Index-Score and all three eating behaviour domains as well as between BMI and the eating behaviour domains. Finally, we found a moderate (r>0·4 and<0·7) association between the eating behaviour domains uncontrolled and emotional eating, and a weak association between the domains emotional and restrained eating.

Table 3 Pearson’s correlation coefficients between socio-economic status (SES; i.e. SES-Index-Score), BMI, eating behaviour and age for men and women (n 5935) aged 18–79 years, LIFE-Adult-Study, Leipzig, Germany, August 2011–November 2014

RS, restrained eating; UC, uncontrolled eating; EE, emotional eating.

*P<0·05.

Parallel-mediation model

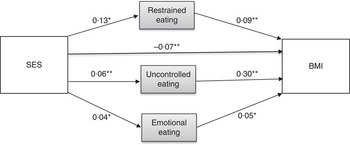

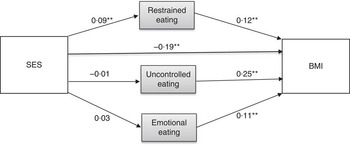

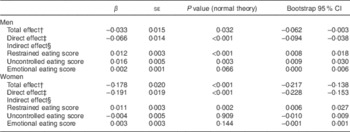

We tested the pathways between SES-Index-Score, BMI and eating behaviour in separate parallel-mediation models for men and for women (see Figs. 1 and 2). In the models, the psychological eating behaviour domains uncontrolled eating, restrained eating and emotional eating were included as potential mediators between SES-Index-Score and BMI. Age was included as a covariate. Results of the mediation models are presented in Table 4.

Fig. 1 Parallel-mediation model between socio-economic status (SES; i.e. SES-Index-Score), BMI and psychological domains of eating behaviour for men (n 2905) aged 18–79 years, LIFE-Adult-Study, Leipzig, Germany, August 2011–November 2014. *Significant path (z-test) with α level of<0·05; **significant path (z-test) with α level of<0·001

Fig. 2 Parallel-mediation model between socio-economic status (SES; i.e. SES-Index-Score), BMI and psychological domains of eating behaviour for women (n 3030) aged 18–79 years, LIFE-Adult-Study, Leipzig, Germany, August 2011–November 2014. **Significant path (z-test) with α level of<0·001

Table 4 Results from the mediation models with direct, indirect and total effects of socio-economic status (SES; i.e. SES-Index-Score) and eating behaviour on BMI for men (r 2=0·032) and women (r 2=0·075) aged 18–79 years, LIFE-Adult-Study, Leipzig, Germany, August 2011–November 2014

† Total effect=direct effect+indirect effects.

‡ Direct effect=path between SES-Index-Score and BMI in presence of mediators.

§ Indirect effect=paths between SES-Index-Score, eating behaviour domains and BMI.

In both men and women, we found a significant direct path between SES-Index-Score and BMI. The effect was estimated as β=−0·07 (se 0·01; P<0·001) for men and β=−0·19 (se 0·02; P<0·001) for women. Regarding the paths between SES-Index-Score, eating behaviour variables and BMI in detail, we found differences between the models for men and women. For men, we found direct significant paths between SES-Index-Score and all three eating behaviour domains (restrained eating: β=0·13 (se 0·02), P<0·001; uncontrolled eating: β=0·06 (se 0·02), P<0·05; emotional eating: β=0·04 (se 0·01), P<0·05). The paths between the eating behaviour domains and BMI were also significant (restrained eating: β=0·09 (se 0·02), P<0·001; uncontrolled eating: β=0·30 (se 0·02), P<0·001; emotional eating: β=0·05 (se 0·02), P<0·05). For women, there were no significant paths between SES-Index-Score and the eating behaviour domains uncontrolled eating and emotional eating, but between SES-Index-Score and the domain restrained eating (β=0·09 (se 0·02), P<0·001). Similarly to the results for men, however, all three eating behaviour variables showed significant paths to BMI also in women (restrained eating: β=0·12 (se 0·02), P<0·001; uncontrolled eating: β=0·25 (se 0·02), P<0·001; emotional eating: β=0·11 (se 0·02), P<0·001). The total effect between SES-Index-Score and BMI regarding eating behaviour variables was estimated as β=−0·03 (se 0·02; 95 % CI −0·062, −0·003) for men and as β=−0·18 (se 0·02; 95 % CI −0·217, −0·138) for women.

Overall, the mediation models indicated a partial mediation by psychological eating behaviour domains in both men and women. In men, restrained eating (β=0·012 (se 0·003); 95 % CI 0·008, 0·018) and uncontrolled eating (β=0·016 (se 0·005); 95 % CI 0·009, 0·030) mediated the association between SES-Index-Score and BMI. In women, a mediation effect of restrained eating between SES-Index-Score and BMI was found (β=0·011 (se 0·003); 95 % CI 0·006, 0·027). Emotional eating did not act as a mediator between SES-Index-Score and BMI in both men and women; results rather showed an independent impact of emotional eating on BMI.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to investigate potential pathways from SES to BMI in the adult population, considering the psychological eating behaviour domains restrained eating, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating as potential mediators stratified for sex. We hypothesized that psychological domains of eating behaviour mediate the association between SES and BMI.

In detail, the eating behaviour factor restrained eating was found to attenuate the indirect association between SES-Index-Score and BMI. This means that low restrained eating might explain higher BMI in lower SES. Higher SES is associated with higher restrained eating. Importantly, restrained eating might be a strong result of individual health considerations. It has been shown that highly educated individuals have higher health considerations, which might in turn lead to restrained eating to stop weight gain, to maintain weight or to lose weight( Reference Ball, Crawford and Mishra 22 ). Thus, this result corroborates health awareness as one important component in weight reduction programmes or in part of health education in general.

We also found a significant mediation effect of uncontrolled eating on the association between SES-Index-Score and BMI. However, as this effect was found only in men, and moreover was only small, further studies may be waited for to confirm this finding. Nevertheless, as the direct association between uncontrolled eating and BMI is well studied, coping with a loss of control in food intake might be part of a weight reduction programme( Reference French, Epstein and Jeffery 14 – Reference Loffler, Luck and Then 17 ).

Emotional eating did not mediate the association between SES-Index-Score and BMI in both men and women. Thus, our analysis suggests that emotional eating is rather directly associated with BMI – independent of SES. The positive association between emotional eating and BMI was also found in several other studies and underlines the importance of this eating behaviour domain for understanding weight gain( Reference van Strien, Frijters and Bergers 13 , Reference Geliebter and Aversa 15 – Reference Loffler, Luck and Then 17 , Reference Konttinen, Mannisto and Sarlio-Lahteenkorva 23 , Reference Horstmann, Kovacs and Kabisch 24 ). Therefore, alternative coping strategies for emotions might be a very useful approach in attempts to lose or to maintain weight independent from one’s social position.

However, regarding the low total effect of all the eating behaviour domains on the association between SES-Index-Score and BMI in mediation analyses, our study, in general, does not indicate a strong mediation effect of psychological domains of eating behaviour. As we were able to focus only on three domains of eating behaviour, more research is encouraged to investigate further potentially important aspects (e.g. social norms, habits, food marketing strategies) in mediation analyses of the association between SES and BMI. Nevertheless, independent from one’s social position, focusing on psychological aspects in a weight reduction process might be a promising approach. Therefore, the identification of internal or external food stimuli, such as food advertising, might help to develop individual coping strategies in a weight reduction process. For example, a review from Mantzios et al. found that ‘mindfulness eating’ might reduce emotional as well as uncontrolled eating, which are both associated with higher BMI values( Reference Loffler, Luck and Then 17 , Reference Mantzios and Wilson 25 ).

Our study is not without limitations. First, there is the probability of selection bias because of a relatively low response rate and some missing information about eating behaviour. Second, individuals with lower SES were under-represented, which might have caused bias, too. Finally, self-reported data of eating behaviour might have also led to some bias, such as over- or under-reporting. Nevertheless, irrespective of these limitations, we found that the association between SES and BMI was partly mediated by eating behaviour.

However, the association between SES and BMI, in general, seems to be complex and there might be more than one pathway involved. To the very best of our knowledge, our study is the first that examined a pathway via the psychological domains of eating behaviour. So far, few studies also examined other potential psychological aspects in mediation analysis. Beydoun et al., for example, found that depressive symptoms may mediate the inverse association between SES and obesity in women( Reference Beydoun, Kuczmarski and Mason 26 ).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all participants and the staff at LIFE–Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases. Financial support: This publication is supported by LIFE–Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases, Universität Leipzig. LIFE is funded by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and by the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the excellence initiative. F.S.T. has been supported by LIFE–Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases, Universität Leipzig. Her collaboration within LIFE was funded by means of the European Social Fund and the Free State of Saxony. Y.B. is funded by IFB Adiposity Diseases. IFB Adiposity Diseases is supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), Germany (grant number FKZ: 01EO1501). Conflict of interest: None of the authors has any conflict of interest to declare. Authorship: M.L., J.T., C.E., A.V., M.S. and S.G.R.-H. conceived and designed the study. A.L. performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. T.L. and F.S.T. helped to interpret the data and to perform the statistical analysis and were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript critically for important contents. A.P. advised in statistical analysis. S.G.R.-H. supervised the study. She as well as M.L., J.T., C.E., A.V., M.S., C.L.-S., A.P., P.K., Y.B., J.B., A.T. and A.H. revised the manuscript critically for important contents. All authors approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig, Germany. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the study.