Teaching patients to recognise the early symptoms of an episode of a recurrent health problem so that they can seek early treatment and limit damage is a well-established secondary prevention strategy for medical disorders such as myocardial infarction. User groups representing people with bipolar affective disorder (e.g. the Manic Depression Fellowship) advocate self-management approaches based on the recognition of the early symptoms of manic or depressive relapse. However, the efficacy of using a health professional to teach patients with bipolar affective disorder to recognise the early warning symptoms of manic relapse and to seek conventional psychiatric treatment was first shown in a randomised controlled trial in 1999 (Reference Perry, Tarrier and MorrissPerry et al, 1999). In this trial, which involved 69 patients with the disorder, the time to the next manic episode was increased four-fold in the intervention group, with a 30% reduction in the number of manic relapses over 18 months. There was no significant change in the time to the next depressive episode nor in the number of depressive relapses over 18 months. The intervention group demonstrated clinically important improvements in function, particularly in employment. A case report illustrating the approach has been published (Reference Perry, Tarrier and MorrissPerry et al, 1995).

Six randomised controlled trials involving 468 patients carried out by four independent research teams in three countries show the efficacy of interventions that involve the identification and management of early warning symptoms of mania and depressive episodes (Reference Perry, Tarrier and MorrissPerry et al, 1999; Reference Lam, Bright and JonesLam et al, 2000; Reference Miklowitz, Simoneau and GeorgeMiklowitz et al, 2000; Reference Colom, Vieta and Martinez-AranColom et al, 2003, Reference Colom, Vieta and Reinares2004; Reference Lam, Watkins and HaywardLam et al, 2003). Additional efficacy against depressive relapses has been achieved with the use of more experienced therapists and the provision of lifestyle advice, including teaching patients additional coping mechanisms for dealing with the first symptoms of depressive relapse (Reference Lam, Bright and JonesLam et al, 2000, Reference Lam, Watkins and Hayward2003; Reference Colom, Vieta and Martinez-AranColom et al, 2003, Reference Colom, Vieta and Reinares2004). The results do not appear to be explained by improved adherence to drug regimens or additional time spent with therapists (Reference Colom, Vieta and Martinez-AranColom et al, 2003, Reference Colom, Vieta and Reinares2004). One randomised controlled trial delivering the identification and management of early warning symptoms for the first 7 of 18 sessions of family therapy demonstrated efficacy against depressive relapses but not mania (Reference Miklowitz, Simoneau and GeorgeMiklowitz et al, 2000). The Manic Depression Fellowship now runs its own self-management training programme based largely on users’ experiences with psychological approaches such as the early warning symptom intervention (for further information, search the organisation's website at http://www.mdf.org.uk).

The purpose of this article is to outline how to deliver a therapeutic intervention to teach patients with bipolar affective disorder to recognise the early warning symptoms of manic and depressive relapse and seek early treatment from health professionals (Reference Perry, Tarrier and MorrissPerry et al, 1999). This approach will be coupled with patient-initiated coping measures to manage manic and depressive prodromes (Reference Lam and WongLam & Wong, 1997; Reference Lam, Watkins and HaywardLam et al, 2003). Definitions of terms used are shown in Box 1.

Box 1 Terms used in this article

Inter-episode symptom Any mood-related symptom that occurs between manic, hypomanic, mixed affective or depressive episodes

Prodrome The build-up in quantity, frequency and severity of inter-episode symptoms immediately before each manic, hypomanic, mixed affective or depressive episode. The term is not restricted to the period before the first episode of illness

Early warning symptoms and signs (early warning symptoms) The symptoms and observed behaviour (signs) that constitute the patient's relapse signature in the prodrome

Relapse signature A selection of early warning symptoms that are used in the early warning symptom intervention to indicate that action needs to be taken by the patient and/or clinical team to prevent a manic, hypomanic, mixed affective or depressive episode

Resources required

The intervention might be performed by a keyworker working in a variety of mental health settings, or by a specialist nurse or psychology assistant in a specialist bipolar affective disorder clinic. An expert patient may be able to teach another patient how to carry out the intervention. In all cases, the intervention is likely to be maximally effective if it becomes a central feature of the care plan, with the assent of the patient's responsible medical officer and other members of the multi-disciplinary team. The responsible medical officer should be involved in key decisions concerning the intervention if it is part of the care plan and should supervise its implementation. The intervention should be reviewed on an annual basis and after each relapse, to update the action plan (early warning symptoms of relapse, health professional contacts and care plan after contact with services), to motivate the patient to use the intervention, and to give him or her confidence that services continue to take the action plan seriously.

In the randomised controlled trial by Reference Perry, Tarrier and MorrissPerry et al(1999), the intervention was delivered by a psychology assistant individually to each patient over 7–12 sessions (a total of 3.5–6 hours of treatment). In the randomised controlled trial by Reference Colom, Vieta and Martinez-AranColom et al(2003, Reference Colom, Vieta and Reinares2004), the specific content of the early warning system intervention took 3 hours to deliver to patients in group sessions. Here, I present the intervention in the form of three 1-hour one-to-one sessions. However, longer will be required if the patient needs to be educated about their condition or does not understand the rationale for the intervention.

Barriers and drawbacks

The patient's relapse signatures have to be ascertained for each pole of illness (mania or depression). Mixed affective states can present with a different relapse signature, and this too should be identified. There is no such thing as a characteristic or typical manic or depressive relapse signature that applies to all patients.

Health services must be prepared to see the patient quickly (ideally within 1 week). The traditional community health team approach of meeting once a week, then allocating the patient an assessment a week or more later will miss the window of opportunity to prevent a relapse. Usually, the patient is best served by seeing someone who is familiar with the intervention and care plan.

The service will need to trust patients’ accounts of their early warning symptoms; patients are likely to be strongly discouraged from using the intervention if the health professional they contact does not believe them, or does not act according to the care plan with sufficient urgency.

Occasionally, patients will seek treatment for early symptoms of relapse that are false positives; sometimes there are other reasons for inter-episode symptoms in bipolar affective disorder (Reference MorrissMorriss, 2002), for example they may be residual symptoms of a previous episode, the result of psychiatric comorbidity, side-effects of medication or normal mood fluctuations. If such a false-positive health contact occurs, the opportunity should be used to explore with the patient the nature and timing of early warning symptoms.

Occasionally, patients become over-confident and wish to rely on this intervention rather than taking mood-stabilising medication. This should be discouraged if there is a clinical need for maintenance medication; a number of trials in schizophrenia show that recognition of early warning symptoms and intermittent use of medication is generally less effective than continuous medication (e.g. Reference Jolley, Hirsch and MorrisonJolley et al, 1990; Reference Gaebel, Frick and KöpckeGaebel et al, 1993). Sometimes when patients monitor their symptoms, they dwell on how depressed they are and seek further treatment for their depression. In such cases, the patients should either be discouraged from using the intervention or taught cognitive–behavioural therapy techniques to manage their depressive symptoms.

Manic prodromes

The early warning symptoms that constitute the manic prodrome are usually qualitatively different from other inter-episode symptoms experienced by patients with bipolar affective disorder. However, each symptom in the manic prodrome is too non-specific to be used alone, so the patient is taught to recognise a number of early warning symptoms occurring together. This ‘relapse signature’ is idiosyncratic to each patient and to each relapse pole (mania or depression).

Both retrospective and prospective research reveals that the nature, timing and order of onset of early warning symptoms are usually consistent from one manic episode to the next. There is usually a 2–4 week period between the patient's first detection of early warning symptoms and the moment insight is lost (and the patient becomes unwilling or unable to seek treatment). However, there is variability in the length of the reported prodrome from one patient to another, with some patients having only a few days’ warning. Carers take about a week longer to recognise the manic prodrome, partly because they are unaware of some of the patient's subjective experiences.

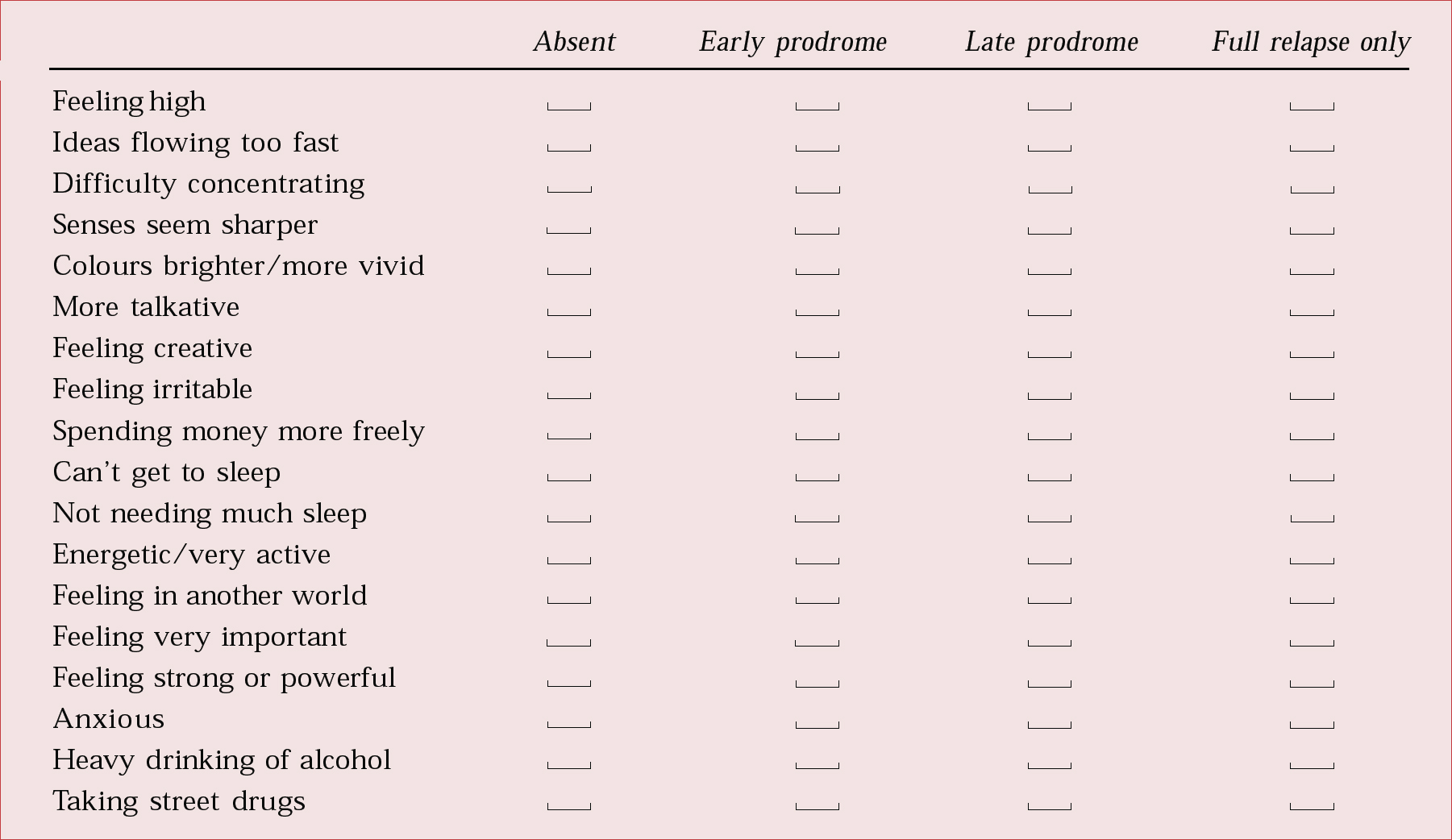

Box 2 outlines a classification of early warning symptoms in manic or depressive prodromes. Figure 1 illustrates some of the more common early warning symptoms in the manic prodromes, but the list is not exhaustive.

Fig. 1 Checklist of symptoms in the manic prodrome.

Box 2 Types of prodromal symptom

Symptoms that are characteristic of a full manic or depressive relapse, e.g. elated or depressed mood

Symptoms that are commonly seen in full relapse but are not diagnostic of manic or depressive relapse, e.g. vivid colours in manic prodrome

Symptoms that are idiosyncratic to the patient's manic or depressive prodromes, e.g. becoming boastful

Signs that are obvious to other people (but not to the patient) and reported to the patient, e.g. playing a particular piece of lively or sad music

Situations that are known to precede the manic or depressive prodrome, e.g. end of tax year, air travel

Depressive prodromes

The early warning symptoms of depressive prodromes are more difficult to detect than those of manic prodromes, because the former may be qualitatively similar to other inter-episode symptoms; patients are looking for a build-up in the severity and frequency of symptoms they experience much of the time, rather than the onset of new symptoms. There is greater variability in the timing of early warning symptoms in the depressive prodrome than in the manic prodrome. However, like the early warning symptoms of the manic prodrome, the nature and order of presentation of early warning symptoms tends to be consistent from one depressive episode to the next. Figure 2 illustrates some of the more common early warning symptoms in the depressive prodrome.

Fig. 2 Checklist of symptoms in the depressive prodrome.

The intervention

Session 1

The aim of the first session is to establish the patient's history, in terms of the number, duration and content of previous manic, mixed or depressive relapses. If there have been numerous previous episodes, the patient is asked to recall in detail the onset and evolution of the first and the most recent, or the most serious and the most recent, manic episodes. These episodes are usually the best remembered. Moreover, the early warning symptoms at the time of the relapse should have been memorable to the individual. The moment that insight (inability to recognise that they are ill and have abnormal symptoms or to accept treatment) is lost is noted down. The patient's account of the evolution of the most recent manic episode is then compared with the evolution of the earlier one. Only symptoms that recurrently and consistently appear early and before insight is lost can be used in the intervention. The patient is shown a checklist of typical early warning symptoms for manic prodromes (Fig. 1) and asked to say which of the symptoms/signs on the list they experience and when they occur in the prodrome. Frequently, patients have symptoms idiosyncratic to their own manic prodrome, and these should be added to the list. The same procedure is followed for depressive symptoms, using the checklist in Fig. 2.

The patient should be asked to complete a mood diary (Fig. 3) for a minimum period of 7 days (or one menstrual cycle) to record normal inter-episode symptoms, the severity of the inter-episode symptoms and their relationship to mood, menstruation and life stressors. Patients who find the recognition of elated mood difficult and easily confused with well-being may need to define each point on the mania scale more closely, according to different degrees of over-activity and to the drive to be more sociable and outgoing. Patients rarely have problems identifying different degrees of depressed mood. If it is necessary to jog the patient's memory concerning the evolution of a previous relapse, their permission to talk to a carer is obtained.

Fig. 3 Mood diary and checklist of prodromal symptoms in mania.

Session 2

The patient and clinican examine the mood diary of inter-episode symptoms and identify any symptoms recorded in the diary that have been previously given as part of the manic prodrome: these should be removed from the list of warning symptoms for that prodrome (examples are shown in Fig. 3). Symptoms appearing in the diary that have been previously identified as part of the depressive syndrome should be reviewed. Any that are relatively mild or infrequent in the inter-episode diary, but build up in severity or frequency before a depressive relapse, may still be used as early warning symptoms for a depressive prodrome. However, those that are already severe, frequent or fluctuate in intensity in the inter-episode diary cannot be used as early warning symptoms.

A card sorting test (Reference Young and GrablerYoung & Grabler, 1985) is used to determine the order of presentation of prodromal symptoms, first in the manic phase, then in the depressive phase. Each prodromal symptom is written on a small card (or a piece of paper) together with the word ‘insight’ on a separate card. The cards are shuffled and the patient is asked to recall their most recent manic episode and to work either forward from the point of no prodromal symptoms to loss of insight, or backwards from loss of insight to first prodromal symptom, placing the cards in order of symptom appearance. The patient is then asked to recall another manic episode that they remember well and the order of presentation of the prodromal symptoms leading up to it. There should be a considerable overlap between the early warning symptoms recognised in the two prodromes recalled. A similar procedure is adopted for depressive relapses. If a carer's account of the evolution of a manic or depressive prodrome and relapse has been obtained, this may be fed back to the patient to stimulate recall. Accounts from the medical notes can also be used to jog the patient's memory.

A minimum of four and a maximum of six symptoms, signs or life situations are used to define the manic relapse signature. Ideally, two or three of these that appear early in the manic prodrome are identified as warning symptoms that will be recorded in the overall action plan, to be completed in session 3 (Fig. 4). These should prompt more intensive monitoring (from weekly to daily) for the presence of the remaining symptoms (the danger symptoms) and also activate coping strategies for dealing with the warning prodromal symptoms. Early warning symptoms that appear later in the manic prodrome are used to define the danger symptoms that should prompt the patient to seek help from health care professionals. The depressive relapse signature is defined in a similar manner.

Fig. 4 The first four parts of an action plan for preventing manic relapse.

Finally, the patient is given some homework to do before the next session: to think of two people they would be prepared to contact if they were experiencing the danger symptoms, signs or situations of a manic or depressive prodrome; and to write down how they coped with the early stages of the manic or depressive relapse – actions or thoughts that worked well or badly.

Session 3

The action plan is drawn up during this session. It has six components:

-

1 ‘warning-level’ and ‘danger-level’ early warning symptoms, signs and situations are listed for both manic and depressive relapse signatures (Fig. 4);

-

2 a series of motivational statements that encourage the patient to act, followed by a plan of action;

-

3 a list of good coping strategies to be acted on at the warning and danger stages (drawn up from the patient's homework and the literature (Boxes 3 and 4; Reference Lam and WongLam & Wong, 1997; http://www.mdf.org.uk) and including the avoidance of poor coping strategies – it is important that patients in depressive or manic prodromes are not left ruminating or brooding on any aspects of themselves or their situation that they perceive to be negative, as this could cause a depressive prodrome to worsen into a depressive episode or a manic prodrome to become a mixed affective state);

Box 3 Good coping strategies for manic prodromes

-

• Restrain myself

-

• Do calming activities

-

• Take extra medication as agreed with doctor

-

• Prioritise and reduce number of tasks

-

• Delay impulsive actions

-

• Talk to someone to bring reality to thoughts

-

• Take time off work

-

• Do not stop prescribed medication

-

• Do not drink or take street drugs

Box 4 Good coping strategies for depressive prodromes

-

• Keep busy

-

• Get myself organised

-

• Get the support of family/friends

-

• Meet people

-

• Distract myself from negative thoughts by doing things

-

• Recognise unrealistic thoughts and evaluate if they are worth worrying about

-

• Do not stop medication or take extra medication

-

• Do not drink alcohol or take street drugs

-

-

4 the names and contact details of three health care services or professionals to whom the patient would turn in the danger stage of a manic or depressive relapse signature; these will be individuals or services who are normally in contact with the patient and whom the patient trusts – usually a psychiatrist, keyworker and/or general practitioner; details of their availability should be recorded, and one of the choices should be a point of access that is always available, such as the accident and emergency department of a local hospital or a 24-hour mental health crisis team;

-

5 an action plan, guiding the management of the patient if he or she presents to one of the named contacts at the danger stage of the manic or depressive relapse signature (the patient should be told that the service is not obliged to follow this care plan if, in the opinion of the health professional contact, a different course of clinical action is in the patient's best interests);

-

6 the patient and the health care professional who has helped in devising the action plan sign a copy of it (printed on headed notepaper); it might help to ask the responsible medical officer, the keyworker (if different from the health professional who devised the action plan) and the carer to sign as well – action plans are sometimes ignored by other health professionals if they are not endorsed by the clinical team responsible for the patient.

There may be advantages to summarising parts 1, 3 and 4 on a small laminated card for the patient to carry in a wallet or purse. The patient should keep a copy of the action plan in a readily accessible place at home. The patient should also try to memorise the key points and refer to the action plan when they need to refresh their memory. Copies of the action plan should be sent to all three health contacts named in it, and a copy placed in the patient's medical notes. The action plan should be considered to be a component of the overall care plan of the patient devised at a multi-disciplinary meeting (such as care programme approach/effective care coordination documentation in UK NHS trusts).

Suitability of patients for the intervention

Patients with bipolar affective disorder are suitable for the intervention if they are at significant risk of relapse and recognise this. They should be euthymic, but have had a relapse in the past 2 years, and should have no prominent psychiatric comorbidity. The bipolar affective disorder should not have an organic cause or be rapid-cycling. Minor psychiatric comorbidity with either DSM–IV Axis I or Axis II disorder is not a contraindication (Reference Perry, Tarrier and MorrissPerry et al, 1999; Reference Colom, Vieta and Martinez-AranColom et al, 2003, Reference Colom, Vieta and Reinares2004). Patients who are currently in episode with mania, hypomania or depression are not suitable, nor is anyone with severe psychiatric comorbidity such as current alcohol misuse or borderline personality disorder. Recently diagnosed patients with bipolar affective disorder may not accept that there is a high risk of further relapse (the risk for non-first-episode patients has been calculated to be around 50% during the 12 months following a manic episode, despite adherence to mood stabilising medication; Reference Tohen, Waternaux and TsuangTohen et al, 1990; Reference Gitlin, Swendsen and HellerGitlin et al, 1995). Therefore, the ideal patient for this intervention has euthymic bipolar I disorder (experiences recurrent mania resulting in substantial functional impairment and depressive episodes) without marked psychiatric comorbidity, who is recognised by both the patient and the clinician as being at high risk of recurrent mania.

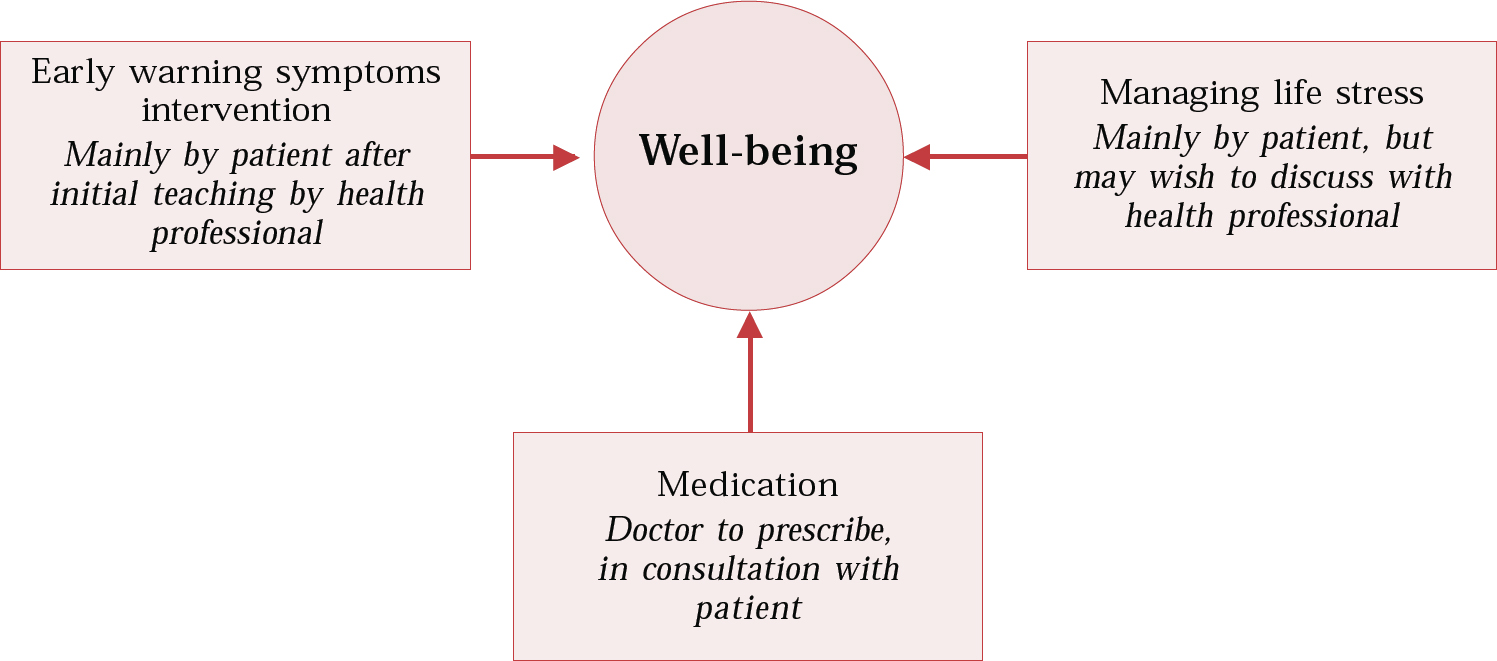

Many patients with bipolar disorder and no severe psychiatric comorbidity eventually achieve a long enough period in remission to learn the early warning symptoms intervention. They like the intervention because it gives them a sense of control over their lives and the confidence to commit themselves to normal psychosocial roles, ranging from independent living and taking a job to going on holiday. However, some patients report that the constant vigilance and ensuing action takes up a lot of energy or makes them feel different from other people. Some become complacent about recognising early warning symptoms or take themselves completely out of psychiatric services, relying on early warning symptoms and medication monitoring by their family doctor. Most patients with bipolar affective disorder see the early warning symptoms intervention as one important component of remaining relapse-free and achieving well-being. Figure 5 illustrates the components of care and the division of tasks that one such patient identified during a recent consultation.

Fig. 5 A patient's perspective on well-being.

Conclusions

This early warning symptoms intervention appears to be effective for patients with euthymic bipolar I disorder without severe psychiatric comorbidity, who are actuarially at substantial risk of further relapse and recognise this risk. Such patients may be taught the intervention in individual or group sessions by a range of health professionals or expert patients (suitably trained and supervised). The help of cognitive–behavioural therapists is required if patients are unable to see the need for the intervention, or attitudes to the early signs of manic or depressive relapse are unhelpful or self-defeating, for example that mania is to be enjoyed (Reference Lam, Bright and JonesLam et al, 2000, Reference Lam, Watkins and Hayward2003). Family therapy approaches incorporating this intervention are helpful when carers are particularly critical and hostile, preventing the patient from using this approach (Reference Miklowitz, Simoneau and GeorgeMiklowitz et al, 2000).

The intervention is now formally recommended as a cornerstone of treatment for bipolar disorder by the American Psychiatric Association (2002), but there is no recognition of the special needs of patients with this disorder in the current NHS plan for mental health in the UK (Reference Morriss, Marshall and HarrisMorriss et al, 2002). As a result, it can be difficult to obtain even the limited resources required to implement this evidence-based intervention, despite the substantial support it has obtained from user groups (http://www.mdf.org.uk). Fortunately, there is growing evidence for the effectiveness of similar interventions v. treatment as usual for patients with a relapsing remitting form of schizophrenia (as opposed to chronic unremitting schizophrenia) (Reference Herz, Lamberti and MintzHerz et al, 2000; Reference Gumley, O'Grady and McNayGumley et al, 2003). Consequently, NHS purchasers and providers may be persuaded to finance the intervention for all patients with serious mental illness in the UK under the assertive outreach, crisis team and early intervention for psychosis initiatives of the NHS plan.

Multiple choice questions

-

1 The manic prodrome is:

-

a idiosyncratic to each patient with bipolar affective disorder

-

b always characterised by sleep disturbance

-

c qualitatively different from other inter-episode symptoms

-

d present for only a few days in most patients

-

e a term used for symptoms that appear in patients before their first relapse.

-

-

2 RCTs of the recognition and treatment of early warning symptoms in addition to treatment as usual:

-

a are not confirmed by surveys of patient experiences

-

b show benefit v. treatment as usual in bipolar disorder but not schizophrenia

-

c show benefits in bipolar disorder with comorbid substance misuse

-

d show benefits in patients with bipolar disorder who are euthymic or mildly depressed

-

e reduce the number, but not length, of manic relapses.

-

-

3 In a service, the early warning symptom intervention:

-

a requires a clinical psychologist to deliver the treatment

-

b has implications for the speed of response of the community mental health team

-

c should be considered as an important part of the care plan

-

d dispenses with the need for maintenance medication

-

e is unsuitable for expert patient programmes.

-

-

4 The intervention:

-

a requires that a detailed patient history be taken

-

b involves recognising symptoms that are present before insight is lost

-

c requires the use of a mood diary

-

d requires the use of a card sorting test

-

e requires carers to keep diaries for the patient.

-

-

5 The intervention includes:

-

a intensive visits by support workers and keyworkers

-

b a keyworker or carer who recognises the early warning symptoms for the patient

-

c an action plan so that the patient knows who to contact if he or she recognises early warning symptoms

-

d an action plan leading to hospital admission

-

e coping measures carried out by the patient.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | T | b | T | b | F |

| c | T | c | F | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | F | d | T | d | F | d | T | d | F |

| e | F | e | T | e | F | e | F | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.