Lady Anne Bacon (c.1528–1610) was a woman who inspired strong emotion in her own lifetime. As a girl, she was praised as a ‘verteouse meyden’ for her religious translations, while a rejected suitor condemned her as faithless as an ancient Greek temptress.Footnote 1 The Spanish ambassador reported home that, as a married woman, she was a tiresomely learned lady, whereas her husband celebrated the time they spent reading classical literature together.Footnote 2 During her widowhood, she was ‘beloved’ of the godly preachers surrounding her in Hertfordshire; Godfrey Goodman, later bishop of Gloucester, instead argued that she was ‘little better than frantic in her age’.Footnote 3 Anne's own letters allow a more balanced exploration of her life. An unusually large number are still extant; she is one of the select group of Elizabethan women whose surviving correspondence includes over fifty of the letters they wrote themselves, a group that incorporates her sister, Lady Elizabeth Russell, and the noblewoman Bess of Hardwick, the countess of Shrewsbury.Footnote 4

Anne's letters have never been entirely forgotten. Thomas Birch's 1754 Memoirs of the Reign of Queen Elizabeth included some extracts from her correspondence and in 1861 James Spedding included whole transcriptions of a small number of Anne's letters in the first volume of his work on her son, as did William Hepworth Dixon in his biography of Francis Bacon.Footnote 5 While these were valuable resources, they only made accessible a very small proportion of Anne Bacon's surviving correspondence. However, in manuscript form Anne's letters have continued to receive attention from scholars working on her sons and their wider circle and, in recent years, they have started to be studied for what they reveal about Anne herself.Footnote 6 A primary obstacle which surely prevents more scholars from using the letters is Anne's handwriting. It has been despairingly described as ‘hardly legible’ and ‘indecipherable’; without long and painful acquaintance, it is decidedly impenetrable.Footnote 7

This edition brings together for the first time nearly two hundred of the letters which Anne sent and received, scattered in repositories throughout the world. It allows fresh light to be shed on Anne's life and on her wider circle, including her children, her sisters, and her privy councillor relatives, as well as controversial figures such as the earl of Essex. Freed from the difficulties of Anne's handwriting, this edition makes accessible the more productive challenges which her letters pose to our knowledge of early modern women. Her correspondence allows us to question, for example, the practical utility of a humanist education for sixteenth-century women, as well as the extent of their political knowledge, from their involvement in parliamentary and local politics to their understanding of political news and intelligence. Furthermore, Anne's letters provide insights into her understanding of diverse issues, including estate management, patronage networks, finance, and medicine, as well as allowing an exploration of her religious views and her experience of motherhood and widowhood.

Although the edition that follows includes letters from all but the first decade of Anne's life, the coverage is uneven. Most of the letters date from after the death of her husband, Nicholas Bacon, in 1579; more particularly, the main body of her surviving letters are those exchanged between Anne and her son Anthony after his return to England in 1592. The types of letters included in this edition also vary: the published, dedicatory letters, which are concentrated in the earlier decades of Anne's life, have a very different function and audience in mind than the quotidian correspondence exchanged between Anne and Anthony during her widowhood, often written in haste. The introduction that follows seeks to outline Anne's biography and the thematic content of the letters, before considering the nature of the archive in more detail and the material issues which influence the reading of her correspondence.

Early life

Anne Bacon was born around 1528 at Gidea Hall in Essex. She was the second of five daughters and four sons born to Sir Anthony Cooke and his wife; her sister Mildred had been born in 1526, and Anne's birth was followed by those of three other sisters, Margaret, Elizabeth, and Katherine. Of her four brothers, Anthony and Edward died while still young, but Richard and William both lived to serve as MPs.Footnote 8

Anne was named after her mother, who was the daughter of Sir William Fitzwilliam, a merchant tailor and sheriff of London, and later Northampton.Footnote 9 Her father, Anthony Cooke, was also politically well connected. After the death of his father, John Cooke, in 1516, he had been raised by his uncle Richard Cooke, a diplomatic courier for Henry VIII, and his stepmother, Margaret Pennington, lady-in-waiting to Katherine of Aragon.Footnote 10 Anthony Cooke was renowned for his humanist education and he acted as a tutor to Edward VI, most probably as a reader after the retirement of Richard Cox in 1550.Footnote 11 It seems that his contemporaries regarded Cooke as largely self-taught and there is no evidence that he attended university.Footnote 12

Education

Sir Anthony Cooke's greatest claim to posthumous reputation is that he provided both his sons and his daughters with a thorough humanist education, in both classical and modern languages.Footnote 13 The Cooke sisters were lauded in their youth for their remarkable learning. Anne was singled out for particular praise in 1551, when John Coke wrote that ‘we have dyvers gentylwomen in Englande, which be not onely well estudied in holy Scrypture, but also in Greek and Latyn tonges as maystres More, mastryes Anne Coke, maystres Clement, and others’.Footnote 14 Walter Haddon described a visit he made to the Cooke household: ‘While I stayed there,’ he wrote, ‘I seemed to be living among the Tusculans, except that the studies of women were flourishing in this Tuscany’.Footnote 15 The Cooke household was therefore acclaimed as a little academy, in which the girls were educated alongside their brothers, reading the same texts. In a copy, in the original Greek, of Moschopulus’ De ratione examinandae orationis libellus (Paris, 1545), Anne wrote the following inscription: ‘My father delyvered this booke to me and my brother Anthony, who was myne elder brother and scoolefellow with me, to follow for wrytyng of Greke’.Footnote 16

Alongside Greek, Anne's childhood education included schooling in Latin and Hebrew, as well as Italian, which she used to translate the sermons of the Italian evangelical Bernardino Ochino. In the prefatory letter which she appended to the first volume of her translated sermons, the twenty-year-old Anne described herself as a ‘begynner’ in Italian, although that may have been an expression of modesty rather than the literal truth (1). Together with her sisters, Anne's schooling also covered the five-part studia humanitatis, extolled by sixteenth-century educationalists, which consisted of grammar, poetry, rhetoric, moral philosophy, and history. Furthermore, her sisters Mildred and Elizabeth were interested in logic and dialectic, so it is possible that Anne also read works on those subjects.Footnote 17

One result of this education was that it enabled Anne to become a translator. Bernardino Ochino had been invited to England in 1548 by Thomas Cranmer, archbishop of Canterbury, to assist with the reform of the English church. In the same year, Anne translated five of his sermons, the text being published anonymously.Footnote 18 By 1551, she had translated another fourteen of his sermons, which were published in two editions that year. One was an anonymous amalgamation of all of Anne's translations, plus a reprint of six of Ochino's sermons rendered into English by Richard Argentine in 1548.Footnote 19 The other 1551 edition contained only Anne's fourteen new sermons, this time printed under her own name.Footnote 20 Thus, by 1551, Anne was known as a published translator in her own right. These publications were Anne's contribution to the evangelical cause. In the prefatory letter to her second set of Ochino translations, she describes her mother's previous dislike of her Italian studies, ‘syns God thereby is no whytte magnifyed’ (2). In dedicating this work to her mother, Anne emphasizes that the activity fulfilled her mother's insistence on godly labour and the letter makes clear her developing Calvinist beliefs in God's determination ‘wythout begynnynge, al thynges [. . .] to hys immutable wyll’.

Anne's scholarly pursuits continued after her marriage to Nicholas Bacon in 1553, shown by her 1564 translation into English of John Jewel's Apologia Ecclesiae Anglicanae. The production of Jewel's original Latin tract was closely associated with her husband's political circle, particularly William Cecil, her brother-in-law.Footnote 21 One of the major challenges facing the nascent Church of England during the early Elizabethan period was ensuring the preaching of the word to the laity. Close analysis of Anne's text reveals her intention to use her translation to engage with these issues, offering a creed for the Church of England, written for a wide readership in plain English.Footnote 22 However, the prefatory letter to the first published edition of the translation, written to Anne by Matthew Parker, the archbishop of Canterbury, chooses to present her text very differently. Parker suggests that Anne conceived the translation as a private, domestic act. He writes that he instigated its publication without her knowledge, stating that such action was necessary ‘to prevent suche excuses as your modestie woulde have made in staye of publishinge it’ (6). The presentation of Anne's translation in the prefatory letter is a deliberate framing device, designed to obscure any suggestion that this translation fulfilled official needs, yet Catholic observers astutely saw through such a ruse. Richard Verstegan later acknowledged Anne's role as translator, perceiving it as part of William Cecil and Nicholas Bacon's ‘plot and fortification of this newe erected synagog’, accurately identifying the usefulness of Anne's work to the early Elizabethan Church of England.Footnote 23

Beyond her activities as a translator, Anne's letters reveal the impact of her humanist training more widely. Five of her letters are written entirely in Latin. She sent two Latin letters to the theologian, Théodore de Bèze; she also received three letters written completely in Latin, including one from her sister Mildred.Footnote 24 The majority of Anne's own letters are written in English, but even in these letters she frequently included odd lines in Latin, Greek, and, more rarely, Hebrew. She turned to classical languages when trying to conceal the contents of her letters, as will be discussed later, or particularly when seeking to persuade her correspondents. Such a motivation was behind her regular adoption of a sententious writing style in her letters. Through classical sententiae, pithy moral quotations, Anne was able to access the persuasive power of the cited authors in her correspondence. For example, she used Seneca's wisdom in his Moral Epistles to bolster her unwelcome advice to her son Anthony regarding his ungodly choice of friends.Footnote 25 Along with Seneca, Anne cited Publilius Syrus, Terence, Horace, and Pindar, as well as drawing on her reading of The Life of Severus Alexander.Footnote 26 Biblical quotations abound in her letters, unsurprisingly given that Anne described scripture as the ‘infallible towchstone’ of all believers (19). Although she used acknowledged and unacknowledged citations from both the Old and New Testaments in her letters, the greatest proportion of biblical quotations in her correspondence is drawn from the New Testament epistles, fittingly given the genre in which she was writing.Footnote 27 In acknowledgement of her learning, Anne's correspondents also frequently adopted a sententious style in their letters to her. Matthew Parker consciously employed such a style when seeking to persuade Anne to intervene with her husband on his behalf in 1568, quoting in Latin from scripture, particularly the Psalms, as well as from Sallust and Horace.Footnote 28 Anne's humanist learning is therefore a constant presence in letters from throughout her life.

Marriage

In February 1553 Anne Cooke married Nicholas Bacon, as his second wife; Nicholas Bacon was a close friend of William Cecil, who had married Anne's sister Mildred in 1545. However, Anne had earlier been courted by Walter Haddon, shortly before he was appointed Master of Magdalen College, Oxford.Footnote 29 Haddon sought the assistance of both William and Mildred Cecil in his suit and when Mildred wrote to her sister to advise that she accept Haddon's hand, she chose to correspond in Latin (3).Footnote 30 Their shared knowledge of the classical language was appropriate for a letter so concerned with the importance of humanist education in sixteenth-century society, but, in spite of her sister's counsel, Anne eventually chose Nicholas Bacon instead of Haddon.Footnote 31

The death of Edward VI ushered in an anxious period for the couple, as they were both well known for their Protestant convictions; not only was Anne the translator of the evangelical Bernardino Ochino, but Nicholas had been closely involved with many of those advancing religious reform during Edward's reign.Footnote 32 On the accession of Mary I, Anne had ridden to join her at Kenninghall in Norfolk and had pledged her support to the new queen. She was thus instrumental in securing Mary's goodwill towards her husband and her brother-in-law, William Cecil, who had been a reluctant witness to the king's instrument to alter the succession. Kenninghall was Robert Wingfield's house and he recorded that Anne was ‘their chief aid in beseeching pardon for them’.Footnote 33 In many ways, Anne's actions in 1553 were fortuitous and contingent on circumstance, for Kenninghall was but a few miles from where the Bacons were then living at Redgrave in Suffolk, but they also reveal her understanding of the unfolding political events.Footnote 34

The Bacons outwardly conformed during Mary's reign, but the years were ones of seclusion. The couple were comforted by their learning. Nicholas Bacon wrote a poem celebrating their shared intellectual interests, which concluded with the following verse:

However, these years were not simply filled with intellectual pleasures. Later letters provide evidence of Anne's domestic skills. Her correspondence reveals that she taught other women how to brew and that she had some culinary knowledge: ‘Trowts must be boyled as soone as possible because they say a faynt harted fysh’ (143).Footnote 36 A verse written about Anne by the clergyman Andrew Willett confirms her expertise in ‘huswifery’.Footnote 37

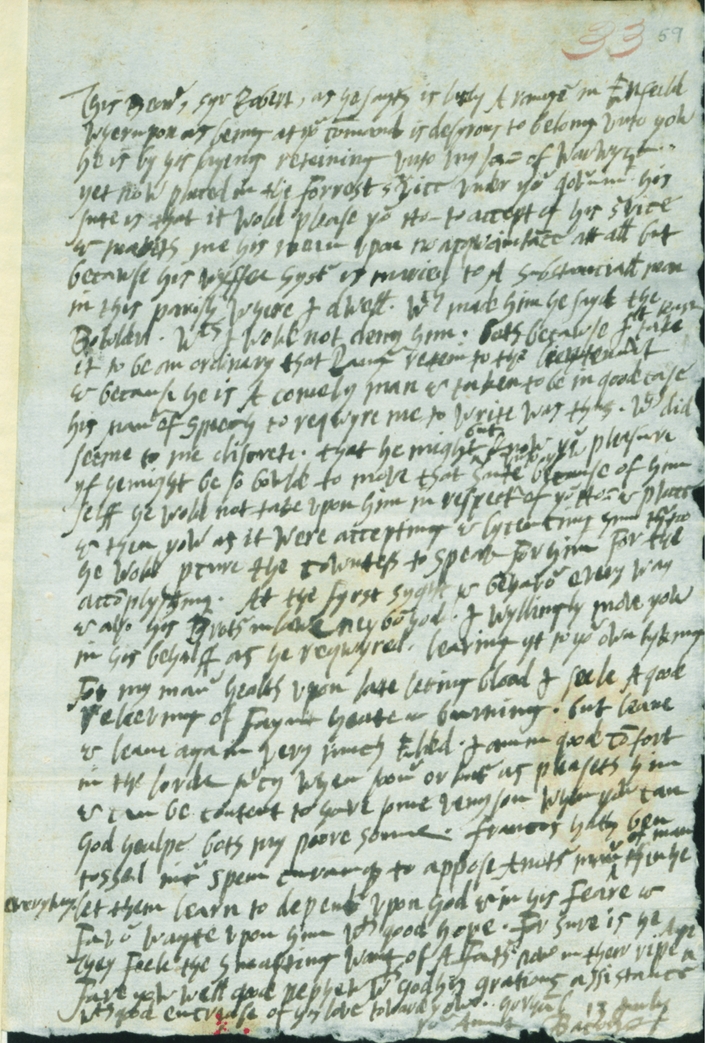

The Bacons’ fortunes rose with the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558, as Nicholas Bacon was shortly after made a privy councillor and lord keeper of the great seal. His position was a source of great pride for Anne, who long into her widowhood recalled her status as a ‘cheeff cownsellour's wyffe’ and widow of the lord keeper (131).Footnote 38 Nicholas bought Gorhambury manor in Hertfordshire in 1560; construction of a new house there was complete by 1568 and thereafter much of the couple's time was split between Hertfordshire and residence at York House in London. The marriage seems to have been a happy one. Anne's frequent postscripts to Nicholas’ letters reveal her intimacy with the contents of his personal correspondence (see figure 1).Footnote 39 She was perceived by others to hold considerable power over her husband: Matthew Parker described her in his letter from February 1568 as Nicholas Bacon's ‘alter ipse’, his other self (7). Parker was loath to write to Nicholas directly, fearing the reception to his overture, but he was convinced that Anne would persuade her husband to help him ensure godly preaching for the people of Norwich.

Figure 1. Nicholas and Anne Bacon to William Cecil, 18 August 1557 (4).

While wife of the lord keeper, Anne contributed a Latin verse to an Italian manuscript treatise entitled the Giardino cosmografico; the work was compiled by Bartholo Sylva, a physician from Turin and Protestant convert seeking favour from the earl of Leicester.Footnote 40 Her sister Katherine and Anne Locke, another contemporary female translator, also wrote dedicatory verses for the treatise in 1571.Footnote 41 A little over a year later, the volume became a vehicle to regain courtly favour for Anne Locke's husband, the ostracized godly clergyman Edward Dering, at which point Anne's sisters Mildred and Elizabeth contributed Greek dedicatory poems.Footnote 42 Nicholas Bacon became the primary examiner of Edward Dering when he was called before the Star Chamber in 1573, and so Anne's name was partially erased from the manuscript, with only her initials remaining and the spaces for the name which would once have read ‘Anna Baconia’.Footnote 43

Motherhood

The marriage brought multiple pregnancies, but only two of Anne's children survived into adulthood, Anthony and Francis Bacon. John Walsall, the Bacons’ household chaplain, later praised the couple's care in ‘demeaning your selves in the education of your children’ (14). Anne's memories of her sons’ boyhoods occasionally come to the fore in her later letters: when she sent pigeons to the adult Anthony and Francis, she sent more birds to her younger son, explaining to Anthony that Francis ‘was wont to love them better then yow from a boy’ (126).

Anne was also close to at least some of her stepchildren during her husband's lifetime. In a letter from 1579, she referred to the long ‘continuance of more then common amytee’ shared with her stepson Nicholas, and a similarly close relationship is testified to by the extant correspondence between Anne and Nathaniel Bacon, prior to her husband's death (15). Nathaniel arranged for his stepmother to be involved in the education of his wife shortly after their marriage.Footnote 44 Anne Gresham Bacon was the acknowledged illegitimate daughter of Sir Thomas Gresham and a household servant. In order that she acquire the gloss of a gentlewoman, Nathaniel arranged ‘to have her placed’ with his stepmother (8). Anne Gresham Bacon wrote to her stepmother-in-law after her return from Gorhambury, stating herself to be ‘greatly bounden to yow for the great care that yow alwaies had of my well doinge duringe my beinge with yow’ (9). Relations were still close in 1573, when Anne Bacon was asked by Nathaniel and his wife to act as godmother to their new daughter; Anne asked her stepdaughter Elizabeth to deputize for her at the christening.Footnote 45

Nicholas Bacon died on 20 February 1579. His will made thorough provision for Anne and it also detailed bequests to the children of both his marriages.Footnote 46 However, the magnitude of the late lord keeper's debts led both branches of the family to dispute their inheritance and William Cecil, by then Lord Burghley, was sought to intervene. The matter was eventually settled by 1580, although Anne's relationship with her stepsons Nicholas and Nathaniel thereafter seems to have been strained.Footnote 47 Although Anne mentioned Nicholas in a later letter, his message was relayed via another family member.Footnote 48 Two years later, Anne did not know in advance that her stepdaughter Elizabeth would marry Sir William Peryam, lord chief baron of the exchequer.Footnote 49 However, Anne's last known letter is to Nicholas, reminding him to pay her annuity on time; there she describes herself as ‘Your Lordship's mother, in the Lord, very frend’ (197).

On the death of Nicholas Bacon I, Anne's elder son, Anthony Bacon, decided to use his inheritance to travel, first to Paris, with the aim of sending intelligence back to his uncle, Lord Burghley, and to Francis Walsingham. In 1581, he moved on to Geneva and stayed with the theologian Théodore de Bèze. Anne felt that the theologian would provide particularly trustworthy paternal guidance, as shown by her letters to Bèze from that year (16 and 17). Anthony's travels then took him to various French cities, with his continued absence from England authorized by the queen.Footnote 50 Walsingham's secretary, Nicholas Faunt, kept Anne apprised of her son's movements on the Continent; in April 1582, he reported back to Anthony that he had met Lady Bacon in Burghley's garden and had answered her questions ‘in all such demand[s] as you may imagin shee did make, touching your estate of health, being, moction of employing your tyme, charges of lyving in those partes, and purpose of further travayle’.Footnote 51

By October 1584, Anthony was resident in the Huguenot town of Montauban, collecting information from Henry of Navarre's court to report back to England.Footnote 52 Increasingly, his continued stay in France caused consternation, never more so than with his mother. In April 1585, Anne petitioned the queen ‘with importune show’ to insist on her son's return; by the end of 1586, she was refusing to send funds to Anthony.Footnote 53 She particularly feared his friendships with the English Catholic figures Thomas Lawson, a servant, and Anthony Standen, a double agent now working for his home country. Lawson felt the effects of Lady Bacon's wrath when sent as a messenger to England in 1588. He was imprisoned for ten months by Burghley, the result of what Anthony later described as ‘my mother's passionate importunitie, grounded uppon false suggestions and surmyses’.Footnote 54 Another messenger, Captain Francis Allen, reported Anne's state of mind in August 1589 regarding her son's continued Continental sojourn: ‘she let not to say you ar a traitre to God and your contry. You have undone her, you sieke her death, and when you hav that you sieke for you shall have but on [sic] hundered pounds mor then you hav now’.Footnote 55 By 1591, Anne was even more resolute to procure Anthony's return; the godly preacher Thomas Cartwright found that he could not persuade her to soften her stance towards her son in this regard, nor induce her to a better opinion of his companion, Thomas Lawson.Footnote 56

There is no evidence, however, that Anne knew of Anthony's prosecution on charges of sodomy in France in 1586.Footnote 57 She received a letter during this period from Michel Berault, the minister in Montauban, explaining her son's continued absence in France and alluding to the fact that she might hear ‘some more serious opinion’ of him; in that case, Berault argued, Anne must ‘immediately set aside the matter’ (20). It is possible that Berault wrote this during the summer of 1586 in response to Anthony's arrest; it could also refer to the hostility that Philippe du Plessis-Mornay and his wife held towards Anthony at this time.Footnote 58 However, Anne's later letters make fleeting allusions to both her sons’ almost entirely masculine lifestyles.Footnote 59 She lamented their lack of wives and her consequent lack of grandchildren, in terms that recalled Anthony's Continental exile: ‘I shulde have ben happy to have seene chylder’s chylder, but Frannce spoyled me and myne’ (188).

Anthony's return: a mother's political counsel

Anthony's return to England in February 1592 marks the start of a voluminous correspondence between mother and son; Anne initially welcomed her son back to the country by letter.Footnote 60 A major concern of this letter, and subsequent correspondence, was how her newly returned son should advance himself in England. The secretary Nicholas Faunt was suggested as a suitable companion, described by Anne as ‘one that feareth God in dede, and wyse with all having experience of our state’ (22). She was concerned that without a detailed knowledge of past political affairs, Anthony would be a poor judge of his new acquaintances. ‘Beleve not every one that speakes fayre to yow at your fyrst comming’, she told him; ‘It is to serve their turn’ (25). His understanding of state matters was a particular cause of anxiety: ‘Yow have ben long absent and by your sickliness cannot be your own agent and so wanting right judgment of our state may be much deceaved’ (32).

For Anne, the combination of her educational background and her hard-earned political experience was a potent one: ‘I think for my long attending in coorte and a cheeff cownsellour's wyffe few preclarae feminae meae sortis are able or be alyve to speak and judg of such proceadings and worldly doings of men’ (131).Footnote 61 Her warning to Anthony about the duplicitous nature of the countess of Warwick, a gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber and one of the queen's closest intimates during this period, was therefore based on past experience.Footnote 62 Her sense of political intelligence was not simply self-aggrandisement. Her political understanding was acknowledged by Matthew Parker: in comparing Nicholas Bacon to three former lord chancellors, Thomas More, Thomas Audley, and Thomas Goodrich, Parker assumed Anne's knowledge of these late politicians. The freedom with which Parker discussed his affairs with Anne contrasts with his statement that he had not spoken of any such matters with his own wife, Margaret Harleston Parker, a woman whom he admitted as being not without ‘reason and godlynes’ (7).Footnote 63

After the death of their father in 1579, the assistance of their uncle, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, was crucial to Anthony's and Francis’ career advancement. Francis, for example, sought help in September 1580 from the lord treasurer and his aunt Mildred in obtaining an honorary legal post from the queen.Footnote 64 On his return from Europe in 1592, Anthony Bacon and his mother expected that Burghley would aid his career. Anne approached Burghley in August 1593 but, while his subsequent letter declared his goodwill towards his nephews, it lacked any practical assurance to further Anthony and Francis.Footnote 65 Anne also approached Robert Cecil in January 1595 regarding Francis’ bid for the post of solicitor-general; after the latter's assurances that his father was seeking to advance his nephew with the queen, Anne concluded that Robert Cecil's ‘spech was all kindly owtward and dyd desyre to have me think so of him’ (116).

Despite such protestations, there is an increasing sense of unease regarding Anne's perception of her Cecil kin. Anne told Anthony in March 1594 that he should be careful in his ‘use’ of his relatives, particularly Burghley (98). Such suspicions were only increased upon the appointment in July 1596 of Robert Cecil to the post of principal secretary, after which Anne told her son, ‘He now hath great avantage [sic] and strength to intercept, prevent and to toy where he hath ben or is, sonne, be it emulation or suspicion, yow know what termes he standeth in toward your self [. . .] The father and sonne are affectionate, joyned in power and policy’ (158). Anthony kept his mother informed of changes in his relationship with his cousin; he told her in December 1596 that Robert Cecil had declared any past ill will as forgotten, with ‘earnest protestation [. . .] he would be gladd and redye to doe me any kinde office’ (183). Such information would have been welcome to Anne; despite her concern regarding Robert Cecil's goodwill towards her sons, he and his father had long been recipients of her more general requests for patronage.Footnote 66

The failure of Burghley to act as a patron meant that Anthony and Francis Bacon sought the advancement of another well-connected figure, Robert Devereux, the second earl of Essex. Francis’ friendship with Essex had begun in the late 1580s and he introduced his brother to the earl on his return in 1592. When the position of master of the rolls became vacant in early 1593, it was widely assumed that it would be filled by the current attorney-general, Thomas Egerton. Essex thus tried to secure the post of attorney-general for Francis Bacon; Anthony relayed his efforts with the queen to Anne.Footnote 67 Anthony declared to his mother in September 1593 that the earl was ‘more like a father then a frende’ towards Francis Bacon, arguing that, if only Lord Burghley would join with Essex, then Francis would succeed in his attempts at preferment (69). However, the Cecils sought to place Edward Coke as attorney-general; Francis, they suggested, would do better to try for Coke's post as solicitor-general. Anthony informed his mother, in minute detail, of the earl's efforts on Francis’ behalf, reporting that Essex told their cousin Robert Cecil, ‘Digest me noe digestinge, for the Attourniship is that I must have for Francis Bacon’ (85). When Edward Coke was made attorney-general on 10 April 1594, Francis’ attentions shifted to securing Coke's old position. His mother, however, feared that his continued struggle for preferment was affecting his well-being, writing that her younger son ‘hindreth his health’ with ‘inwarde secret greeff’ (140).

Despite Anne's appreciation of Essex's efforts to advance her sons, his relationship with them caused her great anxiety. Anthony was soon organizing a secretariat for Essex, which gathered information from across Europe.Footnote 68 To be closer to this operation, Anthony moved from Gray's Inn into a house in Bishopsgate Street in April 1594. His mother was horrified at the relocation, given the lack of ‘edifieng instruction’ and the close proximity to the ‘corrupt and lewde’ Bull Inn (101). After a short residence in Chelsea during the spring and summer of 1595, Anthony had decided to move again, into the earl of Essex's residence on the Strand in August. His mother was opposed to the move from its inception, telling her son ‘yow shall fynde many inconveniences not lyght’ (141).Footnote 69 It would also bring Anthony closer to those whom she worried might infect him with Catholic sympathies. The influence of Anthony Standen and Thomas Lawson had long been a concern, but Anne now feared Anthony's closer association with members of Essex's circle, such as Antonio Pérez, the former secretary of Philip II of Spain, and particularly Lord Henry Howard, later the earl of Northampton. She described Howard as a ‘dangerous intelligencyng man’, adding ‘No dowt a subtill papist inwardely and lyeth in wayte’ (123).Footnote 70

The political circles of Elizabethan London were not the only arena in which Anne sought to guide her son; she was concerned too with his political standing in Hertfordshire. She was a keen observer of local politics close to the Gorhambury estate and she informed Anthony of his failure to be elected as MP for nearby St Albans in 1593; her opinion was that the town had always been set on re-electing the same two principal burgesses and that the offer of support was a superficial one.Footnote 71 Anthony was instead elected MP for Wallingford in Oxfordshire that year.Footnote 72 When he was asked to serve as a justice of the peace, his mother's advice was clear: ‘Take it not yet sonne, si sapis’ (98). Recent work on sixteenth-century women and politics has sought to reconceptualize their activities away from the traditional arenas of politics.Footnote 73 Anne's involvement in local politics, and, as we shall see, parliamentary politics, instead reveals that women in this period understood and participated in these ‘conventional’ political processes.

The counsel of a godly widow

Anne did not only seek to counsel her sons regarding secular politics. Religion is a central issue in her surviving letters, in contrast to the correspondence of many of her female contemporaries.Footnote 74 One reason why Anne wrote so frequently concerning religion in her correspondence is that she felt the need to provide spiritual counsel to her son Anthony. She wanted Anthony to demonstrate his godly credentials clearly on his return to England, especially as he had ‘ben where Reformation is’ (22). She advised him to ensure that his household was ordered upon godly lines, telling him to ‘exercyse godlynes with prayours and psalmes reverently, morning and evening’ (64). Moreover, she urged him to place his trust in those of the ‘syncerer sort’ of religion; she had a particular regard for the Calvinist worship of the French Stranger Church in London (22).Footnote 75

Anne frequently reflects on the spiritual progress of England in her letters from the 1590s. At times she refers to the need for further reform, suggesting that the country was ‘styll wayting for our conversion’ (148). Overall, however, there is a perception of religious decline in her correspondence. The queen was criticized, albeit somewhat obliquely, for her deficiency in stemming such a decline: ‘God preserve her from all evell and rule her hart to the zeallus setting forth of his glory,’ Anne wrote of Elizabeth I in October 1595, adding ‘want of this zeale in all degrees is the very grownde of our home trobles. We have all dalied with the Lorde, who wyll not ever suffer him selff [to] be mocked’ (145). The lack of godly preaching at court was particularly condemned, as infecting not only the queen's counsellors but also beyond through their ‘lamentable example’: ‘For by expownding well the law and commandments of God, sinne is layde open and disclosed to the hearers and worketh in them by God his spirit more hatred of evell and checketh our pronness naturall, to all synn’ (146).

Sections of Anne's letters almost encroach on the masculine domain of the jeremiad sermon, bewailing the misfortunes of late sixteenth-century England as just punishment for society's impiousness.Footnote 76 In April 1595, she wrote that ‘evell dayes [were] imminent to be feared’ (123). She went further in a letter to the ecclesiastical judge Edward Stanhope, condemning his role in England's spiritual decline, through his persecution of godly preachers:

By report, the enemies of God, of her Majestie and of our cuntrie are mighty and with cruell and fiery hartes preparing the readie to the pray and spoile of us all. We had need with most humble submission intreat the Lord of hostes . . . to torne away his wrath so greatlie provoked daily by the fearfull contempt of his holie gospell. (189)

Anne's letters reveal her attempts to inspire personal moral reformation. One particular recipient of her godly counsel was the earl of Essex, who received letters from Anne urging him to cease swearing and his adulterous acts.Footnote 77 She not only attempted to reform Essex's ways directly but also raised her concerns with her son Anthony and with other members of the Essex circle.Footnote 78 Anne's religious counsel was connected to her status as a widow. For her, widowhood was an opportunity to concentrate on spiritual matters.Footnote 79 She told Burghley in a letter from 1585 that she understood she must attend public preaching as ‘a cheff duty commanded by God to weedoes’ (19). Widowhood, however, had a further resonance for Anne, revealed through her correspondence. She chose to sign herself as ‘ABacon Χηρα’ in ten of her letters, ‘Χηρα’ being the Greek for widow.Footnote 80 Two of the letters were directed to the earl of Essex, one went to Lord Burghley, six were sent to her son Anthony, and one was written to her stepson Nicholas Bacon II. It seems likely that Anne's use of the Greek term for widow in these letters derives from the role of godly widows expounded in the Pauline epistles, in his first letter to Timothy.Footnote 81 The biblical passage discusses how poor widows will be maintained and advises that a special group of widows receive assistance from the Church; the passage suggests that in return these godly widows will ‘continueth in supplications and prayers night and day’.Footnote 82 The ten letters that Anne signed ‘ABacon Χηρα’ are united by the fact that they all include some form of intercessory prayer on behalf of the recipient; the letters to Anthony and Nicholas are familial correspondence, covering diverse matters, but all include at least a short intercession. Anne frequently incorporates written prayers in other letters, without the Greek subscription, even explicitly concluding three of these epistolary prayers with an English ‘Amen’ and four with the same word in Hebrew.Footnote 83 In some ways, the use of written prayers is a strategy for offering advice: the value of intercessory prayer for Anne, as a female counsellor, was that she could offer bold and authoritative godly advice through what was a religiously sanctioned act.Footnote 84

‘but quod my Lorde’: reporting speech

When offering both political and religious counsel, Anne relied heavily on incorporating reported speech into her epistolary advice. Linguists have drawn attention to the use of reported speech in other forms of early modern writing, particularly in news serials, and it is striking that Anne's correspondence contains so much reported speech.Footnote 85 She has a particular awareness of the gap between the spoken word and action. She tells Anthony of a conversation between Lord Burghley and a quack physician,

a soden startupp glorious stranger, that wolde nedes cure him of the gowt by boast, but quod my Lorde, ‘Have yow cured eny; let me know and se them’. ‘Nay’, sayde the fellow, ‘but I am sure I can’. ‘Well’, concluded my Lorde and sayde ‘Go, go and cure fyrst and then come again or elce not’. (113)

Her entire conversation with Robert Cecil in January 1595 is reported back to Anthony, and she also records her sister Elizabeth's speech to her in April of that year.Footnote 86 When Anne counsels the earl of Essex against swearing, she reports how she learnt of his behaviour in discussion with a court friend after a sermon and she includes much of the dialogue that ensued, which in turn involves the retelling of an even earlier conversation.Footnote 87

There is the sense that Anne quotes so many speech-acts because they provide evidence for her advice-giving. This, in many ways, is similar to her use of sententiae to bolster her counsel, yet here the usage of reported speech functions as a form of rhetorical proof. Classical and renaissance rhetoricians emphasized that inartificial proofs were particularly persuasive, such as the judgments of earlier courts or the testimony of witnesses.Footnote 88 Anne's reportage of speech-acts, the testimony of her witnesses, is another technique designed to persuade her reader that her epistolary advice was based on strong, incontrovertible evidence.

‘For occurents’

Another basis for Anne's counselling activities was her access to intelligence. There has been much recent scholarly interest in early modern women's involvement with news.Footnote 89 Anne Bacon's letters provide an opportunity to expand our understanding of sixteenth-century women's acquisition of and interest in news. Her correspondence reveals her diverse intelligence networks. She was well served for local news; for example, she knew that Anthony had been approached about becoming a JP before he confirmed the fact to her by letter.Footnote 90 She also maintained extensive contacts at court, including Ursula Walsingham and her daughter Frances Devereux, Lady Mary Scudamore, and Lady Dorothy Stafford.Footnote 91 Sometimes Anne heard news first-hand through conversation with these courtly figures, but on other occasions she received intelligence in letters from the women: ‘My Lady Stafford sent me word that her Majesti marveled yow come not to see her’ (144). Anne even had European contacts who supplied her with news. Captain Francis Goad wrote to her from Dieppe in June 1593 with details of Henry IV's struggles to claim the crown of France, prior to his abjuration of Protestantism the following month.Footnote 92

The greatest source of Anne's intelligence, however, was her son Anthony. His letters supplied her with the latest news from London. Often this was closely concerned with her sons’ personal advancement. Anthony wrote on 5 February 1594 to his mother regarding his brother, Francis; he told her that what followed came to him via the earl of Essex, adding ‘I alter not one worde, thinkinge it best to set it downe as it hath bene delivered from my Lord’ (85). Similarly, a week later, Anthony again wrote to his mother, enclosing a letter written to him by Henry Gosnold, a young lawyer at Gray's Inn, concerning Francis’ reputation.Footnote 93

The news provided for Anne in her letters went beyond information concerning family members. In two different letters, Anthony told his mother of the progress of the investigation of Roderigo Lopez, former physician to Elizabeth I; Lopez was arrested at the end of January 1594 for conspiring to poison the queen and was executed on 7 June.Footnote 94 Anthony also provided information about household appointments at court and about City figures, telling his mother of the death of two London aldermen, one the lord mayor, in December 1596.Footnote 95 Anne was also interested in parliamentary activity. In the aftermath of the April 1593 parliament, Anthony answered each of his mother's queries directly, providing information on the fate of her nephew Sir Edward Hoby after he had quarrelled with a parliamentary committee member, and the consequences of Peter Wentworth's activities to reintroduce the issue of succession into parliament.Footnote 96

European news was also relayed to Anne via Anthony. This was wide-ranging in its coverage; Anthony's letter of 13 July 1596 discussed the Thirteen Years’ War and the Franco-Spanish War, as well as developments in the Nine Years’ War in Ireland.Footnote 97 Much of this information was derived from Anthony's own political contacts with the earl of Essex and his circle. He provided his mother with detailed information regarding the duc de Bouillon's diplomatic activities to forge the Triple Alliance against the Spanish in 1596, much of which seemingly came directly from the Frenchman himself.Footnote 98 Anthony also heard French news through members of the French Stranger Church, which he relayed to his mother.Footnote 99 He was swift to inform his mother of the freshness of the news he provided: details regarding the Thirteen Years’ War and the Franco-Spanish War were provided as ‘newes arrived at the Court yesterday’ (154).Footnote 100

The news from London was sometimes clearly offered in exchange for goods from the Gorhambury estate. A letter from February 1594, reporting the reception of Francis Bacon's first cases in the King's Bench, was concluded, rather prosaically, with an appeal for another quarter of wheat.Footnote 101 Similarly, Francis Bacon concluded a letter lamenting his mother's ill-health with a postscript asking that she send him a bed from Gorhambury.Footnote 102 In each case, the request was seemingly purposefully left until the very end of the letter, as if an afterthought. Anthony's sustained dissemination of news to his mother, however, meant that he continued to facilitate her advice-giving activities, even if he did not always welcome the constant stream of epistolary counsel in return.

Receiving advice

Anne certainly often worried that her advice was mocked and, worse, ignored by her sons, writing, for example, ‘But my sonns hast not to harken to their mother's goode cownsell in time to prevent’ (27).Footnote 103 Her exasperation even caused her to utilize the additional persuasive power of Latin: ‘haud inane est quod dico’ (133). There is little direct evidence of Francis’ reactions to his mother's counsel. When she tried to advise him on how to order his finances in April 1593, he accused her of treating him like a ward, which Anne retorted was ‘a remote phrase to my playn motherly meaning’ (45). Anthony's responses to his mother's advice were varied. Sometimes he resorted to silence, something which enraged his mother and necessitated him providing a further justification:

so in matter of advice and admonition from a parent to a childe, I knowe not fitter nor better answerre then signification of a dutyfull acceptance and thankes, unlesse there were juste cause of replie, which howe reasonable soever it be, manie times is more offencive then a respective silence. (65)

Such cool anger was also frequently his response to what he termed her ‘misconceite[s], misimputatione[s] or causeles humorous threates’ (150). The sheer quantity of correspondence between mother and son, however, suggests that Anthony did value the relationship, if at times only to ensure a supply of goods and money from Gorhambury.Footnote 104 There is also evidence that he read his mother's letters closely. In answer to her comment regarding the stormy weather in June 1596, he responded with a sentiment designed to appeal to his godly mother:

the changes whereof as they were used for threatnings by the prophettes in antient time, so no dout but ^God graunt^ they ^may^ worke more in all goodChristians minde amongst ^in^ us as due and timelie apprehension of God's hevie judgements, imminent over us, for the deep prophane securitie that rayneth to much amongs us. (154)

The many corrections made to this draft suggest that Anthony was trying to please his mother with his response to her advice. Moreover, when he received word of the queen's kind comments about him in October 1593, he was swift to tell his mother, writing that his motivation was not ‘vaine glory’, but that she would be ‘partaker of my comforts, as advertised of my crosses’ (73).

Patronage power

The political roles held by early modern women within their patronage society has been the subject of much scholarly research.Footnote 105 Anne's letters provide evidence as to her role as an intermediary to influential patrons. She would write on behalf of kin: for example, she appealed to Matthew Parker in 1561 for a distant cousin.Footnote 106 After a letter of request by her son Anthony, Anne also wrote to Burghley concerning a wardship dispute involving Robert Bacon, her nephew.Footnote 107 She told her brother-in-law that this was the first patronage request that Robert had ever made of her, and that kinship compelled her to write on his behalf. In this instance, she was more persuaded by their close kinship than was her sister Elizabeth, whom Robert also approached for assistance with the wardship.Footnote 108 Anne also intervened on behalf of servants. When Anthony's servant ‘little’ Peter sought new employment at the Doctors’ Commons, she wrote to Julius Caesar, the master of requests, and to her relative Thomas Stanhope on his behalf, although she was explicit that this was her first and last intervention for Peter.Footnote 109 She would also intervene on behalf of neighbours in Hertfordshire, if they shared her godly beliefs.Footnote 110

During her widowhood, Anne's energies as an intermediary were particularly focused on intense support of godly preachers, in response to John Whitgift's attempts to enforce religious conformity as archbishop of Canterbury from 1583. Nicholas Faunt described Anne's activities at court on behalf of the suspended preachers, writing to her son Anthony ‘that I have bene a wittenes of her earnest care and travaile for the restoring of some of them to their places, by resorting often unto this place to sollicite those causes’.Footnote 111 Her letter to her brother-in-law, Lord Burghley, from February 1585, demonstrates not only the nature of her religious beliefs but also her willingness to use her family connections to further the godly cause. Anne was ‘extraordinaryly admitted’ through Burghley's favour into the House of Commons, when Whitgift gave his response to a petition against his ‘Three Articles’, which had led to the suspension of many godly preachers.Footnote 112 Following this particularly heated session, Anne asked that her brother-in-law, perhaps with other privy counsellors, grant some of the godly preachers a private audience:

And yf they can not strongly prove before yow owt of the worde of God that Reformation which they so long have called and cryed for to be according to Christ his own ordinance, then to lett them be rejected with shame owt of the church for ever. (19)

Despite Anne's energetic petition, there is no evidence as to any positive outcome from her appeal to Burghley.

Anne also acted as a religious patron in her own right. In his letter of 1581, Théodore de Bèze suggested that his dedication to Anne of his meditations on the penitential psalms was inspired purely by her humanist learning.Footnote 113 However, the dedication was a calculated move. In 1583 and 1590, Anne donated funds to the Genevan church.Footnote 114 In 1593, she was once again prevailed upon to contribute to the European cause and was presented with a recent edition of Bèze's meditations.Footnote 115 However, Anthony's letters reveal that no contribution was forthcoming from her, so he himself sent a gift to Bèze. The draft of his letter to his mother, explaining the gift which he had sent, is revealing through its multiple corrections and additions, as Anthony struggled to find the right words to write to his mother.Footnote 116 It would appear that by 1593 Anne was less predisposed to donate to the European cause, perhaps because her primary concern was with local provision of godly preaching.

Anne's letters thus reveal her considerable support of puritan preachers at Gorhambury in the 1590s. In May 1592, she made reference to the ‘comfortable company’ of Percival Wyborn and Humphrey Wilblood, both of whom had been deprived of their benefices. Her condemnation of those who persecuted the godly was clear: ‘Thei may greatly be afraide of God his displeasure which worke the woefull disapointing of God his worke in his vineyarde by putting such to silence in these bowlde sinning dayes’ (26). Wyborn and Wilblood stayed at Gorhambury at various points throughout the early 1590s, providing ‘fatherly and holsome heavenly instructions’ to the household and local community (185).Footnote 117 Anne frequently tried to send them to her sons in London; she urged that Anthony should interpret the visits of these ‘learned men [. . .] as tokens of [God’s] favour’ (58).

During her widowhood, Anne presented the clerical livings to two benefices in Hertfordshire: St Michael's in St Albans and the nearby Redbourn parish. Her clerical presentations were all godly preachers, who were subjected to close scrutiny by the ecclesiastical authorities.Footnote 118 The archdeaconry of St Albans was under the diocese of London at that time and John Aylmer, bishop of London from 1577 to 1594, was described by Anne as a ‘godles Bishop’, committing even worse persecution in her eyes than the Marian bishop Edmund Bonner (103). Those serving the archdeaconry of St Albans were described as ‘byting vipers, the hole pack of them [. . .] hindrerers of goode men’ (102).Footnote 119

Anne's correspondence reveals in detail the dealings of one of her clerical choices, Rudolph Bradley, with the ecclesiastical authorities. Appointed vicar of Redbourn parish in 1592, Bradley was required to send a certificate of orders in February 1597 to Edward Stanhope, chancellor to the London diocese, and, on the latter's failure to receive them, Bradley was declared excommunicate.Footnote 120 Anne's response was to send a vehement letter of reproach to Stanhope, arguing that his role should instead be to ‘incouradge the faithfull and painefull preachers of Jesu Christ’ (189). After further intervention from Anthony Bacon, Bradley was reinstated and continued at Redbourn until 1602, although Anne refused to see herself as beholden to Stanhope, whom she had earlier condemned as a ‘fylthy adulterer, yf not fornicator too’ (163).Footnote 121 Anne's correspondence concerning Bradley reveals her belief that if the parishioners were not guided by a preacher, they would fall away from godly living; she wrote to Anthony that she feared that, in the absence of scriptural instruction from the pulpit, ‘Now belyke Robin Hoode and Mayde Marian are to supply with their prophan partes, for leave is geven’ (33).

Anne's letters demonstrate that even after clergymen ceased to live under her direct patronage she continued to perceive them as being under her care; in 1597, she used her connections with the earl of Essex to help William Dike, who had previously been an assistant curate at St Michael’s, even prevailing upon her son to add his influence to her suit.Footnote 122 Edward Spencer, one of Anthony's servants, wrote to his master in August 1594 from Gorhambury, informing him of Anne's financial support of godly preachers: ‘Mr Willcockes had a paper withe agrete delle of gould in it, Willblod had 2 quartares of whete, Dicke had somthinge the other day, what I know not’.Footnote 123 Anne's local religious patronage as a widow even went beyond her own clerical candidates. In 1589, Thomas Wilcox, one of the authors of the 1572 Presbyterian manifesto, An Admonition to the Parliament, wrote of the ‘sundrie favours’ she had shown towards ‘many worthie ministers’ over the years (21).

Anne has also long been associated with the puritan apologia, A Parte of a Register, published in 1593. John Field was responsible for collecting this mass of documents recording the struggle of the godly; the aim was to form a puritan register which would imitate Foxe's Acts and Monuments. William Urwick, the Victorian historian of nonconformity, suggested that A Parte of a Register was ‘probably issued with the sanction and at the expense of Lady Bacon’ and this suggestion has been echoed by later scholars.Footnote 124 A letter written by Anne in July 1593 to Anthony makes a cryptic reference, perhaps to the documents that formed the Register: ‘I wolde have the two kallenders very saffly returned hether’ (58).Footnote 125

Sisterhood

Despite the fact that Anne's historical reputation is partly based on her status as one of the learned Cooke sisters, little mention is made of her sisters in her letters. Nicholas Bacon's letter to William Cecil, husband to Anne's sister Mildred, refers to Elizabeth and Margaret Cooke as living with the Cecils during the Marian period, although Anne's postscript to the letter makes no further direct mention of her sisters.Footnote 126 There is greater evidence of Anne's relationship with Elizabeth during their widowhoods. She referred to receiving a letter from Elizabeth Cooke Hoby Russell, but stated that she had replied, advising her not to visit in person while she was unwell.Footnote 127 She borrowed her sister's coach on occasion and visited her Blackfriars house after attending Stephen Egerton's sermons at the nearby St Anne's church.Footnote 128 There Elizabeth tearfully revealed their nephew Robert Cecil's rejection of her advice. Anne's response was to write to Robert on her sister's behalf, but Elizabeth was resolutely opposed to such a course: ‘“No, no”, inquit, “It is to late, he hath marred all and that against my cownsells lyking at all”’ (125).

Anne counselled her sons not to take notice of their aunt's actions, or become embroiled in such courtly intrigue. Elizabeth, Anne believed, could be a fickle ally; she told Anthony that Henry Howard would surely betray him to his aunt Elizabeth.Footnote 129 There is evidence in Anne's letters that her sister certainly did try to become involved in Anthony's affairs. In October 1593, he told his mother that he had heard from his aunt that the queen had openly lamented his ill-health and three years later Elizabeth Russell tried to heal the mistrust which had developed between the two sides of the family, the Bacons and the Cecils, since Robert Cecil's elevation to the secretaryship in July 1596.Footnote 130 To assuage this bad feeling, Elizabeth went to and fro between her brother-in-law, Burghley, and her nephew Anthony, on 8 September 1596.Footnote 131 That Anthony was suspicious of his aunt's intentions was confirmed by a later letter to his mother. He told her that he was pleased that his aunt had solicited a profession of goodwill from Burghley, stating that her mediation ‘hath dried upp the torrent of my Lord Tresurer's mightie indignation, at the least by show and his owne profession and so autenticall a testemony as my Lady Russell’s’ (172). In the reference to Elizabeth's ‘autenticall’ testimony, there is surely the suggestion that, like his mother, Anthony felt that his aunt would publicize her actions.

Inheritance and finances

Anne's letters provide important evidence regarding the financial dealings of a sixteenth-century woman, which complements recent research on eighteenth-century women and their money.Footnote 132 It seems that Anne kept relatively detailed accounts; in June 1596, for example, she broke down the £220 of payments made by her that year.Footnote 133 Her sons proved a great and unpredictable drain on her finances. A frequent refrain in her letters is that she had spent all her wealth on them: ‘Goodes shall I leave none as mony or plate [. . .] I have ben too ready for yow both till nothing is left’ (44).Footnote 134

Many of Anne's letters discuss the financial ramifications of her husband's will. Francis Bacon's financial difficulties stemmed from the fact that he had been less well served by his inheritance, gaining some marsh lands in Kent and in Essex.Footnote 135 Due to her ‘natural love and affection’ for her younger son, Anne granted him the manor of Marks and associated land near Romford, Essex, in January 1584; however, her grant had the proviso that, upon payment of ten shillings, Anne could void the agreement.Footnote 136 Anne and Francis jointly leased the manor to George Harvey in October 1584.Footnote 137 In April 1592, Francis, ignoring the conditional nature of the grant from his mother, mortgaged Marks to Harvey, the lessee.Footnote 138 In order to repay £1,300 on 30 April 1593, Francis proposed selling Marks to Harvey, although he needed his mother's agreement. Anthony reminded her of her ‘motherlie offer’ to bestow the whole interest in Marks upon his brother (42), but Anne initially angrily protested that Francis had told her he would not part with the property, but would instead borrow money from other creditors; she then softened her stance, but demanded that Francis produce a written note of all his debts and that she handle the financial settlement with Harvey.Footnote 139 Francis responded with outrage, to which Anne protested that her ‘playn purpose was and is to do him good’ (45). Francis rejected his mother's offer on such terms and instead arranged a second mortgage with Harvey on 26 May 1593, which he repaid in full in May 1594.Footnote 140 Marks was again mortgaged to Harvey in May 1595, but Anne seems to have released all her interest in the property, for Francis alone conveyed the property to Harvey in May 1596, when unable to find the funds to reclaim the manor.Footnote 141

Anthony had been better served by his father. He had inherited the three Hertfordshire manors of Minchenbury, Abbotsbury, and Hores in Barley, although the estate was entailed and his half-brother Nicholas had an interest as ‘remainderman’, which meant that he would have inherited the estate on the death of Anthony.Footnote 142 Nicholas Bacon II therefore had to approve any sale of the land. Several of the letters discuss Anthony's attempts to sell Barley in 1593.Footnote 143 Difficulties arose because Nicholas was loath to agree to the sale.Footnote 144 The potential buyer of the estate, Alderman John Spencer, also drove a very hard bargain.Footnote 145 An indenture dated 4 September 1593 records the sale of Barley estate to John Spencer, although the agreement of Nicholas was still uncertain.Footnote 146 Anne also gave her life interest in the manors of Windridge, Burston, and Napsbury in Hertfordshire to Anthony on 10 November 1593, along with lands around Gorhambury and Redbourn rectory, with the proviso that she could reclaim them for the payment of 20 shillings.Footnote 147

In spite of waiving her interest in these properties, Anne repeatedly argued that the sale of land for reasons of expediency caused her sons’ financial ruin. ‘Have yow no hope of posterite?’, she asked Anthony. ‘Only my chyldern cownted in the worlde unworthy their father's care and provyding for them’ (188). The last evidence of Anne's activities before her death concerns these inherited properties: on 1 March 1606 she gained licence to alienate Gorhambury manor and on 14 June 1608 she received a pardon for improperly alienating her interest in the manors which she signed over to Anthony in November 1593.Footnote 148

Anne's letters also reveal that she paid many of her sons’ bills.Footnote 149 She questioned the huge bill that Anthony had run up for coal in the summer of 1596; likewise, the bill of £16 for coal in March 1597 was declared by Anne to be ‘monstrous’ (194).Footnote 150 She also questioned Anthony's grocery bills. She asked the grocer himself to inform her of her son's balance, without Anthony's consent; Robert Moorer told her that Anthony owed him £15 or £16 and that his bill had not been settled since the previous autumn.Footnote 151 Anne advised that this was a common ploy and one she had known used by the apothecary Hugh Morgan, who had treated Nicholas Bacon; Morgan had wanted to wait until prices rose to submit his bills, rather than submit them quarterly, although Anne sought to counteract this scheme.Footnote 152 Anne stated that she would pay the grocer's bill for Anthony only if he would sign an itemized version, for fear he was being overcharged.Footnote 153

It was not only money that Anthony and Francis required of their mother; goods and services from Gorhambury were sought by the brothers to save further expenditure. Anthony thus made frequent requests for goods from Hertfordshire, particularly for beer.Footnote 154 Anne's letters often detail plans for the transportation of beer to London, along with other produce from the estate, including game birds, fish, and strawberries.Footnote 155 Francis also asked his mother for household implements, for he had discovered, he reported, ‘howe costlie the buyinge of it newe is’ (91). Anne complained that her sons stripped the Gorhambury manor of all its finery; in response to Anthony's request for a long carpet and the pictures of the ‘ancient learned philosophers’, she lamented ‘yow have now bared this howse of all the best’ (133). The exchange only very occasionally went the other way. Anthony sent Spanish dainties and wine to Anne from London; the latter was not for herself, Anne protested, but to offer to the clergymen who regularly visited her at Gorhambury.Footnote 156

At home in Hertfordshire: Gorhambury manor

Barbara Harris has shown that aristocratic widows in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries were energetic estate managers.Footnote 157 Anne's letters provide later evidence of such activity, revealing in close detail her management of the Gorhambury estate during her widowhood. Anne had considerable involvement in the leaseholds held by some of the Gorhambury tenants. These were fixed-term agreements, bounded either by a number of years or by life span.Footnote 158 She often interceded on behalf of tenants with her son and she also had the authority to grant new leases.Footnote 159 The lease held by Hugh Mantell, Anthony's steward, was described by Anne as ‘subtile and combersome’ and she sought further advice on how to proceed (61).

She was also forthcoming in passing judgement on tenants, again advising caution from Anthony at his return from Europe: ‘they wyll all seek to abuse your want of experience by so long absence’ (27). Furthermore, the letters reveal Anne's concern with the Gorhambury manorial court. Every manorial lord had the right to hold such a court and they enforced the manorial customs, copyhold land transfers, and local community matters, including the administration of local justice for minor crimes.Footnote 160 Although it had some powers of social control, the court leet, held once or twice a year, had greater powers concerning local order, such as regulating misbehaviour, including drunkenness and assault.Footnote 161 These courts were usually presided over by a steward, often a senior estate official, appointed by the lord of the manor.Footnote 162 Anne was adamant that William Downing, a London notary, should act as steward for the Gorhambury courts, ideally with the assistance of the lawyer Thomas Crewe.Footnote 163 She also revealed a particular interest in holding regular sessions of the court leet, which may suggest that she valued its ability to enforce social regulation.Footnote 164 She certainly noted tenants who had particular business with the court; William Dell's ‘nawghty dealing’ meant that her court steward ‘hath had much a doo with him’ (82). Anthony's letters reveal that he was happy to leave the organization of the court to his mother: ‘For the time of keeping the Court, as it hath ben, so shall it be allwaies of your Ladyship's pleasure and appointment’ (119).Footnote 165

In line with Anne's interest in the moral regulation provided by the court leet, her letters reveal her concern with behaviour on the estate and in the local parish. Her fear was that ungodly behaviour would spread: ‘I wrong my men lyving well and christianly in their honest vocation to suffer them to be ill entreated and my selff contemned’ (125). Yet Anne encountered difficulties in exerting her authority over Anthony's multiple inherited manors. Many of Anthony's tenants clearly recognized Anne's jurisdiction over her son's properties. She interceded for a tenant from the Barley estate, who had heard that his farm was to be sold by Anthony; Anne protested that the same family had dwelt in the farm for a hundred and twenty years and so should continue there.Footnote 166 Yet nearby properties held by Anthony also represented a threat to Anne's authority at Gorhambury. She argued that her position was contested by Anthony's men from his Redbourn estate, stating that ‘Idle Redborn men have hunt here allmost dayly; yf I were not syckly and weak I wolde owt my selff with all kind of doggs against them and kyll theirs’ (93). She told Anthony that she must be held in authority over her own servants and over Gorhambury manor: ‘Elce I geve over my authorite to my inferiours, which I think is a discreadit to eny of accompt that knows rightly their place from God’ (194).

Anne's interactions with Edward Spencer, another of Anthony's servants, provide further evidence of the difficulties that she had in establishing her authority. During the summer of 1594, Spencer relayed to his master in a series of letters from Gorhambury how ‘unquiet my Lady is with all her household’, suggesting that Anne was in dispute not only with her household servants but also with Anthony's friends and servants at Redbourn manor:

She have fallen out with Crossby and bid him get him out of her sight. – Now for your Doctor at Redbourn, she saith he is a Papist or some sorcerer or conjurer or some vild name or other. – She is as far out with Mr. Lawson as ever she was, and call him villain and whoremaster with other vild words.Footnote 167

Previous scholarship has placed emphasis on Spencer's accounts as evidence of Anne's mental instability, together with the later testimony of Godfrey Goodman, bishop of Gloucester, who wrote that Anne was ‘little better than frantic in her age’.Footnote 168 Yet Anne's collected letters reveal that she and Spencer were regularly in dispute, and that undue weight should not be placed on his testimony from the summer of 1594; Anne described him in May 1593 as ‘an irefull pevish fellow yf he be looked into and checked for his loose demeanour’ (48).Footnote 169

Anne's authority was partially contested by her status as the life-tenant at Gorhambury; many of her servants thus looked towards Anthony as their master instead of her. Anne acknowledged the difficulty of her position: ‘I have it as I myght not, greving liberly to their hurt and my discredit, because I wold yow shulde every way be well and comfortably here’ (127). Anthony promised not to interfere with his mother's business and, on occasion, actively sought to defend her from attacks on her authority. In January 1594, Winter had acted towards Anne with ‘undewteyfull demeanour and speeches’, according to Anthony Bacon, who came to hear of his mother's treatment (81). He urged his mother that Winter should ‘be called to account’ for his words and actions; as he was at Redbourn, Anthony proposed sending Richard Lockey, a principal burgher of St Albans, to intervene on his behalf. Anne's response was to reject his offer, entreating her son not to call upon Lockey: ‘He is an open mowthed man with owt all discretion, full of foolysh babling. He wolde make all the town ryng of his foolyshnes. I pray yow defend not me this way; I nether lyke it ner nede.’ Anne argued that she was accustomed to such treatment and so she did ‘rather contemn then regarde’ (80). Yet the combination of her decreasing status and her decreasing funds was a source of much grief to her: ‘I am halff impotent now my selff,’ she wrote in July 1596, ‘and every thing decaies with me’ (161).

Medicine

Early modern women's interest in medicine has been well established, particularly through analysis of the textual evidence of women's expertise in healing.Footnote 170 Anne's letters contain frequent discussion of afflictions and their treatment. She regularly described her own health to Anthony and asked for details about his state in return. When suffering from kidney stones, Anthony told his mother that he was in much less pain after having passed three stones, ‘the leaste as bigge as a barlie corne’ (65). Anne was concerned that her sons’ loose living caused their ill health; she lamented that Francis’ weak stomach was exacerbated by ‘untimely late going to bed and then musing nescio quid when he shuld slepe and then in conseqwent by late rising and long lyeing in bed’ (27). Her great fear in terms of health was extreme behaviour of any kind: ‘Extremitees be hurtfull to whole, more to the syckly’ (28). Keeping to his bed would only prolong Anthony's gout, in her opinion: ‘The gowt is named pulvinarius morbus because it lyketh softness and ease’ (62). She feared that taking the warm water on a trip to Bath would only increase Anthony's ‘hote’ gout (50). Too strong beer was also mistrusted as it would ‘bestur’ the gout (133). Purging was questioned as too extreme, for Anne told her son ‘me thinkes it shuld make nature nether to work digestion ner strength being so long still pulled’ (196).

Anne feared the actions of certain doctors, particularly those whose prescriptions were too extreme. Much of her knowledge of kidney stones and gout was drawn from her experience of her husband's affliction with the same complaints.Footnote 171 For example, when Anthony was suffering from kidney stones, she told him that his father had found relief by anointing his genitals with oils, drinking almond milk, and taking a bath strewn with herbs; describing the bath, she told her son, ‘Yf yow wyll lett me, I wyllingly wyll come and make it for yow’ (84). It may be that Anne also first learnt the effectiveness of distilling strawberries for their medicinal properties when treating her husband (29). Other positive first-hand recommendations of treatments were also trusted. After receiving encouraging reports from her stepson Nicholas, Anne suggested that leeches might bring comfort from the gout.Footnote 172 Ultimately, she considered that illness was providentially ordained, a sign of ‘fatherly correction’ (133).Footnote 173 The only sure cure was prayer, through which God would work in the ‘syck body to the reviving of his sowle’ (120).

Composition

The content of the letters, discussed in detail above, needs to be considered in relation to their composition. Most, but not all, of Anne's letters are written in her own hand. While this means that her message was unmediated by a scribe, it poses its own difficulties, both for the contemporary reader and, presumably, for her sixteenth-century readers. Anne's hand, a loose form of italic, is infamously difficult to decipher.Footnote 174 It has been noted that it was acceptable for high-ranking men and women to have illegible handwriting, labelled by Graham Williams as ‘uglyography’; Anthony Bacon described the earl of Essex's hand to his mother as being as hard to read as any cipher, ‘to those that are not thoroughlie acquainted therewith’ (73).Footnote 175 Anne's handwriting may reflect her sense of high status, but it certainly worsened as she aged (see figures 1 and 2). The fact that her letters are almost all in her own hand did not preclude the involvement of others in their composition; for example, she sent drafts of important letters to her son for his advance approval before sending.Footnote 176

Figure 2. Anne Bacon to Robert Cecil, 13 July 1594 (109).

Almost all of Anthony's letters, and those of most of Anne's other correspondents, are not holograph. Most of Anthony's extant letters to his mother are drafts. It is likely that he worked closely with his secretaries over their composition, but it is impossible to reconstruct the particular authorship roles held in this process.Footnote 177 As has been discussed, the various changes made to these drafts reveal the effort placed upon their composition and the message that Anthony sought to convey to his mother. There are complex issues regarding the composition of other letters in the edition, too. Anne Gresham Bacon's letters to her stepmother-in-law are actually in her husband's hand, revealing his role in their composition.Footnote 178 There are also questions regarding the composition of the letter from Mildred to Anne in 1552. The letter, seeking to persuade Anne to accept the proposal of Walter Haddon, is actually written in Haddon's own hand, so may possibly have been composed by him; more probably, however, Haddon was shown and then made a copy of Mildred's letter of advice.Footnote 179

Furthermore, epistolary conventions dictated the form of some of the letters in the edition. Anne's sister Mildred owned a copy of Erasmus’ letter-writing manual, De conscribendis epistolis, and Anne's own letters reveal her familiarity with contemporary epistolary practices.Footnote 180 The majority of Anne's correspondence is familial. Erasmus had designated that such letters should be defined as a separate category of correspondence, differentiated from the classical rhetorical categories of judicial, demonstrative, and deliberative correspondence. In terms of internal structure, then, most of Anne's letters are freely formed, although her letters to Essex, unlike the majority of her correspondence, occasionally adopt the formal rhetorical structure of early modern letters.Footnote 181

Epistolary conventions also had an impact on specific areas of Anne's letters. Letter-writing manuals were explicit that the wording of the subscription should be reflective of the social status of the writer and the recipient. In The Enimie of Idlenesse (1568), William Fulwood made the point that sixteenth-century correspondents writing to their superiors must close by stating ‘By your most humble and obedient sonne, or servaunt, &c. Or, yours to commaund, &c.’; inferiors only necessitated a sign-off of ‘By yours, &c.’.Footnote 182 Such social considerations govern Anne's writing of subscriptions. To potential patrons, such as Théodore de Bèze or Edward Stanhope, Anne's subscription noted that she was the ‘late Lord Keper's widow’ (189).Footnote 183 As has been discussed, she used the Greek for widow, ‘Χηρα’, in ten of her letters. To her sons, her subscriptions varied; generally she closed with ‘Your mother’ in either English or Latin, but she also used the subscription to amplify the emotional persuasion of the letter. In December 1594, she felt that she needed to emphasize her status as a godly widow and affectionate mother, signing off as ‘your loving and careful mother for yow. ABacon Χηρα’ (114). On other occasions, too, the personal descriptions used in subscription reveal Anne's emotional state. After informing Anthony of the death of John Finch in 1593, she signed the letter ‘Your sad mother, ABacon’ (72). In this, she followed the practice of her sister Elizabeth, who likewise utilized the subscription of her letters to bolster their emotional resonance.Footnote 184

The addresses or superscriptions, providing the name of the recipient and their location, included on the outside of the letters, are also illuminating. Details are provided as to the necessity for swift carriage: a letter to Anthony in May 1595 was addressed with the note that it was to be carried ‘with some spede’ (129). Sometimes notes were even written on the outside of letters, perhaps because news had reached Anne after the rest of the epistle had been sealed. ‘Part not with your London howse temere ne forte peniteat tei’, she wrote on the outside of a letter to Anthony in June 1595 (135).

The material nature of Anne's letters also has much to tell us about how the letters would have been read. The use of space on the page was significant in early modern letters; the space between the salutation and the main body of the letter, and between that and the subscription, reflected deference towards the recipient, in an age when paper was an expensive resource.Footnote 185 It has been remarked that, in practice, such conventions governing the use of space were often loosely followed and Anne Bacon's letters reflect a general application of this principle. Letters to Théodore de Bèze and to the earl of Essex all have a marked space between the salutation and the body of the letter (see figure 3).Footnote 186 On occasion, there is some space left between the body of the letter and the subscription; the greatest space left in any of her surviving letters between the main letter and her sign-off is in her second letter to Théodore de Bèze, but even then Anne did not place her subscription at the bottom of the page, indicating that, while she wanted to show Bèze deference, she was aware of her own status as the ‘widow of the Lord Keeper’ (17).Footnote 187

Figure 3. Anne Bacon to Robert Devereux, earl of Essex, 23 December [1595] (146).