The conditions of production are at the same time the conditions of reproduction.

—Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1Footnote 1A nitroglycerine advertisement in the January 1868 issue of the Mining Journal boasts, “The EXPLOSIVE FORCE of this BLASTING OIL is TEN TIMES that of GUNPOWDER, and the ECONOMY and SAVING in TIME, LABOUR, and COST in removing granite and hard rock, in sinking shafts, driving tunnels, and opening forward in close ends is immense” (fig. 1).Footnote 2 Mining, drilling, and mineral resource extraction accelerated exponentially under the global force of nineteenth-century industrialism, transforming space but also, as this advertisement suggests, time. “All that is solid melts into air,” wrote Marx and Engels in 1848, illuminating how the solid commodities of nineteenth-century extraction took on fluid and atmospheric capacities with the rise of fossil-fueled industry.Footnote 3 Time, too, would change states under the regime of coal-powered extraction, a regime that was variously said to speed up time and to save time, to make the future from the deep past or the present from the near future.

Figure 1. Advertisement from the Mining Journal, 4 January 1868, 13.

The rise of industrial extractivism occasioned a complex reckoning with prevailing ideas of time and futurity; it saw the imagining of a new future, one that was, in key ways, undetermined and indeterminable—in other words, open. This new sense of time was born of the perception that future human life could not continue to be sustained by the stock of underground resources that powered industrial society. For the first time in history, social life was understood to be premised on a nonrenewable material base that was depleting toward exhaustion. Rather than pointing toward a future endpoint or collapse, however, nineteenth-century extraction literature posits an unknown future, an undead future, a future that recedes as we move toward it. While the prospect of an “open future” may sound positive, this literature presents it rather as bereft of the cyclical comforts of a stable, predictable natural system.

Just as the rhythms of agricultural life and labor are bound up in the forms of the pastoral, the age of industrial extraction, I argue, ushered in a new sense of human-natural relations and a new literature. From metals to minerals to coal, the nineteenth century saw a ramping up of extraction as the steam engine and other new technologies, including new explosives, contributed to an unprecedented scale of extraction and the global establishment of an extractivist version of ecological imperialism.Footnote 4 With steam, deeper mines could now be dug and, crucially, drained, enabling entirely new dimensions of depth within extractive industry. In the sacrifice zones of Britain and its empire, industrial terraforming pulverized the land, casting up at least as much waste and damage as it did treasure. While extraction in its most primitive methods predates recorded history, large-scale industrial mining was a nineteenth-century phenomenon, and the magnitude of its environmental impact extended deeply into human culture and into the literary, textual, and aesthetic forms of the nineteenth century.

The temporal structures of provincial realist novels set in extraction landscapes convey a growing nineteenth-century sense of extraction-based life as untethered to the seasonal rhythms of the living earth, and they convey a new conception of futurity imbued with the realization that Britain was now reliant on an industrial system powered by a nonrenewable, diminishing stock of resources. Such novels are premised not on the human life cycle, like the bildungsroman, nor the seasons of the year, like the pastoral; they are instead premised on the notion of a depleted or undead future. This future is “open” in the sense that it will not grow from the past—it will have been drained by the past. This was a future born of the nineteenth-century convergence of industrialization, imperialism, and global capital, which together produced a new stage of environmental history: the age of industrial extraction. As the steam engine and other industrial technologies were transforming the scale and effects of mining, nineteenth-century cultural discourse around exhaustion, supply, futurity, and decline reached a new stage as well, leaching into the endings, trajectories, and temporalities of that characteristic nineteenth-century literary form, the realist novel.

Reproductive Futurity and Extraction Capitalism

This article will focus on three realist novels set in landscapes of extraction: Joseph Conrad's Nostromo (1904), George Eliot's The Mill on the Floss (1860), and Fanny Mayne's Jane Rutherford; or, The Miners’ Strike (1853). All three depart from the conventions of the marriage plot—or at least from the assurances of reproductive futurity that typically accompany this plot—and such deviations from chrononormativity, I will argue, reflect the new understanding, which accompanied the rise of fossil-fueled capitalism, of an extraction-based life claimed at the expense of future generations.Footnote 5

Let me clarify, to begin, that my use of the “no future paradigm,” as some critics have called it, emerges from the work of postcolonial and feminist critics focused on environmental justice rather than the work of Lee Edelman, whose No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (2004) is better known in literary studies. Edelman's critique of reproductive futurism made a key intervention into U.S. queer theory but does not easily scale out to an analysis of global or transspecies justice, nor translate readily into such domains as indigenous or environmental justice critiques, which are often animated by a sense of ethical obligation to future life—human and nonhuman alike. As Neel Ahuja has argued, the climate crisis asks us to think “more broadly about reproduction than Edelman does, recognizing that bodies and atmospheres reproduce through complex forms of socio-ecological entanglement.”Footnote 6 Viewed in this light, all humans are engaged in reproductive processes, whether they realize it or not, yet given ongoing rates of species extinction and climate-related threats to precarious human communities, we are now witnessing what Ahuja describes as a “staggering scale of ‘reproductive failure,’ human and nonhuman.”Footnote 7

Macarena Gómez-Barris sees extraction capitalism at the heart of the “‘no future’ paradigm,” and in her recent analysis of South American extraction regimes and the social movements opposed to them, she contrasts the “‘no future’ model that is extractive capitalism” with the growing movement toward “transgenerational stewardship” that is visible, for example, in recent South American legal frameworks that grant “rights to future generations.”Footnote 8 Gómez-Barris situates her argument squarely within queer feminist thought and yet maintains that any “critique of reproductive futures has to be balanced against the historical weight” of eugenics and anti-indigenous policies, which have sought to fix indigenous populations in the past and deny their claims on the future.Footnote 9 Similarly, Maristella Svampa describes how resistance to extraction regimes in South America has built on a “strengthening of ancestral struggles for land by indigenous and campesino movements,” and how such movements encompass “the defense of the common, biodiversity, and the environment.”Footnote 10 Here the framework of ancestral and multigenerational collectivity has enabled a powerful critique of extraction capitalism and the depleted future it offers. Thea Riofrancos has similarly discussed extractivismo in Ecuador and the success of the anti-extraction movement there in achieving a legal basis for an expanded notion of territory “as a space of cultural and ecological reproduction.”Footnote 11

Ecofeminist critics focused on North America have similarly emphasized reproductive futurity writ large—a global, transspecies affair—as a key component of environmental justice. Indeed, given that the human communities most under threat from climate change are communities of color, many recognize an urgent need to insist on this point in the interest of racial justice as well as transspecies justice. Naomi Klein, drawing on the work of indigenous feminists, has posited an environmental “right to regenerate” as “the very antithesis of extractivism, which is based on the premise that life can be drained indefinitely.”Footnote 12 Despite key differences in emphasis, recent work by Donna Haraway can be situated alongside such an argument; Haraway's call to “make kin not babies” asserts the need for a massive reduction in the planet's human population, but Haraway makes this call in the name of humans and other species who face an uncertain future, perhaps even extinction, in these “times of burning and extraction called the Anthropocene.”Footnote 13 Earth's growing human population, Haraway says, “cannot be borne without immense damage to human and nonhuman beings.”Footnote 14 Her work thus shares the aim of ensuring a future for earthly creatures, even though she insists on the ethical gains of “staying with the trouble” and “learning to be truly present.”Footnote 15

In my view, learning to be present will also require attending to the past, for the present is long, extending backward into the historical circumstances that produced it. Today, two centuries into industrial life, we find ourselves in the midst of a complex, many-sided environmental crisis whose scope we are still struggling to grasp, and many of the most pressing hazards associated with this crisis—such as climate change and air, water, and soil pollution—have resulted from the extraction ecologies of industrial capitalism that emerged in the nineteenth century. Attending to this present crisis means attending to the conditions that produced it. The provincial realist novels under discussion here were all created under a regime of accelerating imperial extraction, but while two are set in England, one is set in South America—a reminder of how, in the early days of industrial extraction especially, the provincial and the colonial were both targets for sacrifice and exploitation.Footnote 16 In addition to shared features of setting, the three novels also share the same strangely open temporality of extraction capitalism, resulting in a similar handling of reproductive futurity. By grouping them together I hope to convey the temporal and geographical features of extraction ecologies—features that deeply impressed nineteenth-century literature in the age of the extraction boom.

Extraction Ecologies

My use of this phrase, “extraction ecologies,” is intended to suggest a tension between its two key terms: the word “extraction” is from the Latin extrahĕre, to draw out, and its first definition in the Oxford English Dictionary is “the action or process of drawing (something) out of a receptacle; the pulling or taking out (of anything) by mechanical means.” “Ecology,” on the other hand, was first used in 1866 by German biologist Ernst Haeckel to denote the principles of interrelationality and interdependence that characterize natural life: “By ecology, we mean the whole science of the relations of the organism to the environment including, in the broad sense, all the ‘conditions of existence.’ These are partly organic, partly inorganic in nature.”Footnote 17 While the underlying idea of “extraction” thus presumes the ability to withdraw one component from the “receptacle” of nature, “ecology,” by contrast, suggests a complex of interdependences from which no one part can be removed in isolation. Literature of the industrial era, I argue, found new ways to convey such interdependencies: to show how the extraction of underground material is entangled with a complex array of socio-environmental causes and effects, and how the living and nonliving earth are dynamically bundled together.

Recent work by such critics as Jason Moore has demonstrated how this dynamic bundling is obscured within the history of capitalism. In Capitalism in the Web of Life, Moore argues that “capitalism depends on a repertoire of strategies for appropriating the unpaid work/energy of humans and the rest of nature outside the commodity system,” including “the congealed work of extremely ancient life (fossil fuels) … useful for capital accumulation.”Footnote 18 The longstanding Enlightenment project of externalizing nature, of separating “nature” and “society” in binary opposition, Moore says, has prevented us from recognizing capitalism's dependence on the work of what he calls “cheap nature,” the “process of getting extra-human natures—and humans too—to work for very low outlays of money and energy.”Footnote 19 It would seem to confirm this reasoning that while studies of Victorian labor have been quite attentive to mining—arguably the signature form of work within the labor movement of the day—and its social history, we have not tended to consider the miners’ plight within a larger ecology of mining, one that includes humans and nature bound together.

To examine mining and extraction in this light will, I hope, contribute to an urgent project with which our field is now engaged: the project of reconceptualizing the nineteenth century by way of the fossil fuel economy it engendered, an economy that took root and expanded quickly in the decades following the Industrial Revolution, but which has proved obstinate in its staying power and difficult to move beyond. The nineteenth century saw the moment of our entanglement in this particularly insidious form of path dependency, as we can now see in W. Stanley Jevons's 1865 declaration that coal is “the Mainspring of Modern Material Civilization. … Coal, therefore, commands this age—the Age of Coal.”Footnote 20 Andreas Malm's recent book Fossil Capital explores in detail the historic shift from water power to steam power in the 1830s English textile industry as the moment when, “at a certain stage in the development of capital, fossil fuels become a necessary material substratum for the production of surplus-value.”Footnote 21 In Victorian literary studies, Jesse Oak Taylor's The Sky of Our Manufacture: The London Fog in British Fiction from Dickens to Woolf has helped us think about the effect of coal-burning on the atmosphere of London and on the climate imaginary of Victorian literature, while Allen MacDuffie's Victorian Literature, Energy, and the Ecological Imagination has traced “the contours of our ongoing energy crisis” in Victorian narratives that both map and mystify the energy regime they depict.Footnote 22

My goal is to reframe this ongoing discussion around extraction itself and to position coal within a broader network of nineteenth-century extractive industries—a global infrastructure of labor, capital, and material devoted to the unearthing of buried treasure. Extraction, I will suggest, possessed social and aesthetic forms of its own, and during this period of rapid environmental change, nineteenth-century literature adapted to convey in a new way how extraction is bound up in industrial ecologies and in the conditions of existence that govern modern life. Literature captured a new vision of civilization in which humans were now dependent on finite, nonliving, nonrenewable stores of earthly resources, incapable of replenishment through seasonal rebirth. Pre-industrial trajectories of closure, completion, and revival gave way to an uncertain horizon of exhaustion, and this transformation is expressed in novelistic form. Just as the ecology and economy of industrial Britain are bound up in extraction, I argue, so too does its literature exhibit forms and features of extraction, particularly in its temporal imaginary.

Exhaustion Temporalities

Before turning to the three provincial realist novels that will be my focus here, let me touch briefly on a few social scientists who were theorizing extraction in the time that these novels appeared. Just as these thinkers were grappling with the prospect of extractive exhaustion, provincial realist novels were similarly grappling with the consequences for a society built on a finite supply of exhaustible material. Together, the social science and the literature reveal the open temporal structure that inheres in extraction ecologies: one that defies trajectories of renewal and rebirth but also trajectories of progress and fulfillment.

W. Stanley Jevons's The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal-Mines (1865) is one such text that attempts to account for the social and temporal conditions of extraction-based life. Influential and widely circulating, The Coal Question is a long rumination on exhaustion as a material threshold and its remarkably complex timescale. The study was taking part in what was, by 1865, a decades-long debate about the threat of coal exhaustion in England.Footnote 23 Prior to writing it, Jevons spent five years in Australia at the height of the gold rush, and if he saw firsthand how gold extraction can produce the accelerated pace of a “rush,” he was at pains a few years later to warn England that its ever-intensifying rush for coal would ultimately run up against a terminal pressure in the form of exhaustion: “A farm, however far pushed, will under proper cultivation continue to yield for ever a constant crop. But in a mine there is no reproduction, and the produce once pushed to the utmost will soon begin to fail and sink to zero.”Footnote 24

Jevons's emphasis on the lack of reproductive capacity within extraction ecologies was typical of Victorian political economists and other observers of coal. John Holland's The History and Description of Fossil Fuel (1835; 1841) emphasizes that because coal is “incapable of reproduction or increase,” all established consensuses about “free trade … do not legitimately apply.”Footnote 25 He adds that coal, tin, lead, and other extracted commodities “differ so essentially from other articles produced by English industry” because of their “prospective exhaustion, at some remote period” and the “undoubted fact, that our mines are not inexhaustible.”Footnote 26 Louis Simonin's Mines and Miners (1868) similarly stresses the difference between timber and fossil fuel, noting that the “management of collieries … is far more interesting than that of forests and coppices, for the coal when removed does not grow again.”Footnote 27 The extraction economy thus implied a new relation to futurity, and Jevons accordingly insists in The Coal Question that Britain's coal reserves be measured in time rather than volume; in the graphs that appear opposite the title page of Jevons's book, centuries are the primary unit of measurement, going up to the year 2000 (fig. 2). Glossing the bottom graph, Jevons writes, “supposed future consumption of coal at same rate of progress showing the impossibility of a long continuance of that progress.”Footnote 28

Figure 2. Graphs, inside front cover, W. Stanley Jevons, The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal-Mines (London: Macmillan, 1865).

Such Victorian hand-wringing about coal exhaustion may seem tragically misguided from the perspective of today, at a historical moment of reckoning with the geological fact that there is far too much coal in the ground for our own good, far too many fossil fuels buried beneath us for our atmosphere to bear. Indeed, from a policy point of view, our best course of action to prevent the worst-case scenario would be precisely to leave the coal, oil, and gas in the ground, not for the use of future generations but for their survival. This represents, in some ways, a clear distinction between the Victorian extraction debate and our own, but there are continuities as well. If Jevons and others worried about a finite store of coal and other extracted materials, we now worry about a finitude of sinks in which to discard their waste products—not just the CO2 emitted by fossil fuel combustion but also the heavy metals of e-waste and other toxic remainders of extraction. Moreover, even in the nineteenth century many social scientists recognized that exhaustion is not determined by supply, or at least is not only determined by supply. In The Coal Question, for example, despite Jevons's ostensible focus on the time frame of exhaustion, he strains to identify the moment at which such a conclusive endpoint might occur. He admits that mines might always be dug deeper and are only constrained by costs and risks from doing so; that other parts of the world, beyond England, might contain rich coal stores; and that new mining technologies may lead to new profits even in abandoned sites. Exhaustion thus emerges as a temporal threshold determined in large part by economics (that is, the viability of profit in a particular mine) and demographics (that is, the rate of consumption, which depends on population) rather than geology or capacity.

Decades prior to Jevons, Alexander Humboldt's Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain (1811) offered a similarly constructivist account of resource exhaustion—that is, one emphasizing social rather than geological factors—in surveying Mexico's mining potential for European investors, but Humboldt leaned heavily on an imperialist notion of an expandable resource frontier to offset the finitude of underground resources. He had spent formative years in and around the German mining industry, and it was this early experience that prepared him to map the mines of Mexico during his travels in Latin America. His essay confronts the strangely undead timescales of extraction capitalism—noting that in “a great number of works of Political Economy … it is affirmed that the mines of America are partly exhausted, and partly too deep to be worked any longer”—but claims that the vast frontier works against this tendency: “The abundance of silver is in general such in the chain of the Andes, that when we reflect on the number of mineral depositories which remain untouched, or which have been very superficially wrought, we are tempted to believe, that the Europeans have as yet scarcely begun to enjoy the inexhaustible fund of wealth contained in the New World.”Footnote 29

Humboldt's essay was edited and published in England in 1824 by John Taylor, mining engineer and treasurer to the Geological Society, with the explicit goal of encouraging British investment in Mexican mine schemes. As Taylor glossed Humboldt for his British audience, “if the skill and experience in mining which we possess, and the use of our engines, could ever be applied to the mines of Mexico, the result would be that of extraordinary profit.”Footnote 30 Such arguments, Sharae Deckard writes, created “a myth of the ‘metallick wealth of Mexico’ which almost single-handedly produced a British investment boom in silver mining,” but when the “boom went bust in 1830, Humboldt was widely blamed for exaggerating Mexico's production capability.”Footnote 31 Again, extraction works against constructions of time that resolve in discrete endpoints; extractive exhaustion emerges in the social-scientific literature as resembling that “untravelled world” of Tennyson's “Ulysses,” “whose margin fades / For ever and for ever when I move.”Footnote 32 Mines can be brought back from the dead—a circumstance that foreshadows the “comic faith in technofixes” that Donna Haraway identifies with Anthropocene notions of futurity—but mines can also die again, at least in a provisional manner.Footnote 33

Extraction, Provincial Realism, and Nostromo

Such a sense of undeadness hovers over the San Tomé silver mine in Joseph Conrad's 1904 novel Nostromo, a novel that unites provincial realism with aspects of the colonial adventure story, just as it brings together the temporality of extractive exhaustion with new spatial conceptions of the expanding resource frontier that emerged within extractive imperialism. John Plotz has described the experience of provincial life in the Victorian provincial novel as one of “semi-detachment,” “far away from the seemingly inescapable centrality of the metropolis, yet still connected to it”; this rhymes with Nathan Hensley and Philip Steer's recent description of Costaguana, the fictional South American setting of Nostromo, as a “place [that] has yielded its natural resources for the benefit of those elsewhere.”Footnote 34 Within Costaguana, much of the novel's action takes place in the town of Sulaco, which, the narrator says, “had never been commercially anything more important than a coasting port.”Footnote 35 But ports turn out to be key arenas of action within extraction regimes, since they connect remote mines to the centers of finance—in this case, San Francisco, a city that was bred, if not born, of the California Gold Rush.

While Victorian novels set in London, as Jesse Oak Taylor and Allen MacDuffie both emphasize, are pervaded by the combustion of coal, we must go outside the city, to provincial and colonial settings like Costaguana, to see resource extraction rather than consumption in the nineteenth-century fictional landscape. My focus on provincial realism goes, to some extent, against the grain of recent urgings that ecocriticism turn to speculative and nonrealist genres as a corrective to an earlier overemphasis on realism, but I find that the temporal structure of the provincial realist novel—which is heavily reliant on the marriage plot, the inheritance plot, and the ideal of social reproduction—intersects with extraction temporalities in remarkable ways.Footnote 36 My argument thus concerns the temporality of extraction ecologies as depicted by provincial realist novels set in extraction zones amid the nineteenth-century extraction boom: an open temporality that defies trajectories of progress associated with normative versions of futurity.

Macarena Gómez-Barris has used the term “extractive zone” to refer to “the colonial paradigm, worldview, and technologies that … reduce life to capitalist resource conversion,” and has pointed to the “successive march of colonial and neocolonial actors operating in relation to South America as if it were an extractible continent.”Footnote 37 The newly industrialized British Empire played its part in this particular parade, and Conrad's Nostromo can be read within this history, but while there has been a good deal of recent work on Nostromo that discusses the novel in terms of financialization, institutionalization, and the place of both within the imperial project of global capitalism, few critics have discussed at any length the “material interests” at the base of such developments: the extraction of silver from the San Tomé mine.Footnote 38

With its large cast of characters, Nostromo’s pivotal node is not, in fact, the eponymous sailor Nostromo but rather the San Tomé mine itself, whose abandoned status initially causes its unwilling recipient, Gould Sr., to be haunted by dreams of the undead. After being granted the unproductive mine from the Costaguana government as a means of getting more taxes from him, Gould Sr. “became at once mine-ridden, and … began to dream of vampires.”Footnote 39 His son Charles, who will inherit the mine, grows up being “told repeatedly that [his] future is blighted because of the possession of a silver mine” (44). This has the inevitable result that mines come to acquire “a dramatic interest” for the young Charles: “Abandoned workings had for him a strong fascination. Their desolation appealed to him like the sight of human misery, whose causes are varied and profound. They might have been worthless, but also they might have been misunderstood” (45). The San Tomé mine is neglected to the point where it “was no longer an abandoned mine; it was a wild, inaccessible, and rocky gorge” (42), but it comes to give again under the right pressures; after studying mine engineering in Europe, Charles Gould, the so-called “English man of Sulaco,” manages to revive it into a “fabulously rich mine” (31).Footnote 40 The mine's trajectory is in no way straightforwardly progressive, however, for it generates not just wealth but war, exposing the connection between extraction regimes and warfare now conveyed by the term “conflict mineral.”Footnote 41 Conrad's novel suggests how Britain's “informal empire” in Latin America, as Robert Aguirre and others have described it, contributed to this dynamic by way of investment and commerce.Footnote 42

Interwoven with the history of the mine is the story of a marriage and its own downward trajectory, and the romance between Charles and Emilia Gould is from the beginning a romance of extraction. In their courtship, they visit a marble quarry, “where the work resembled mining in so far that it also was the tearing of the raw material of treasure from the earth” (46). After they wed, Charles's resuscitation of the mine is described as “in essence the history of [Mrs. Gould's] married life” (51). At first she “talk[s] of the mine by the hour with her husband with unwearied interest and satisfaction” (53), but by the end of the novel, the marriage has proven to be a disappointment in its temporal features: “It had come into her mind that for life to be large and full, it must contain the care of the past and of the future in every passing moment of the present” (373). For Mrs. Gould, this means children, and the children never come, which is in some obscure way because of the mine: “she saw clearly the San Tomé mine possessing, consuming, burning up the life of the last of the Costaguana Goulds. … The last! She had hoped for a long, long time, that perhaps—But no! There were to be no more” (373). Here, exhaustion's temporal features pervade the provincial realist marriage plot, denying its normative resolution. A similar frustration happens with two other thwarted marriages in the novel: between Nostromo and Giselle Viola, and between Martin Decoud and Antonia Avellanos—neither of which comes off due to the premature deaths of Decoud and Nostromo. The exhausted futurity that all these broken and infertile marriage plots point toward is captured in the novel's terminal line, which conveys the ghostly horizon that inheres within extraction ecologies: “away to the bright line of the horizon, overhung by a big white cloud shining like a mass of solid silver, the genius of the magnificent [Nostromo]”—who is dead by this point in the text—“dominated the dark Gulf containing his conquests of treasure and love” (405).

Exhausted Futures and The Mill on the Floss

The nonproductive and unfulfilled marriage plots of Nostromo mirror those of other provincial realist novels that foreground extraction ecologies, including George Eliot's The Mill on the Floss (1860). Eliot's second novel is set at a water-powered mill during the 1830s, at a historical moment of energy transition from water power to coal-fired steam power, and features its own thwarted romance—between Maggie Tulliver and Philip Wakem—whose courtship unfolds mostly in an abandoned quarry called the Red Deeps. Here Eliot, like Conrad, adapts the provincial realist novel's long-standing focus on social renewal by way of marriage, reproduction, and inheritance to the extraction-based society of industrial Britain, undergirded by a temporal structure of exhaustion rather than seasonal renewal.

Discussion of the possible conversion of Dorlcote Mill to steam courses through Eliot's novel, along with a general sense that the world is speeding up on the back of coal-fired capitalism.Footnote 43 As Maggie's uncle Deane puts it, “It's this steam, you see, that has made the difference: it drives on every wheel double pace, and the wheel of fortune along with ’em.”Footnote 44 If extraction shapes The Mill on the Floss’s temporal forms by way of coal and steam, it also shapes its landscape, for the abandoned quarry known as the Red Deeps is a key setting in the novel and is a place haunted by exhaustion, “broken into very capricious hollows and mounds by the working of an exhausted stone-quarry, so long exhausted that both mounds and hollows were now clothed with brambles and trees” (316). Eliot does not specify the type of stone that was quarried here, but she is most likely thinking of ironstone, given the redness of the dirt and the fact that Lincolnshire, where the novel is set, was the richest site in England for ironstone mining. Ironstone was typically mined from open pits or quarries, especially in the area around Scunthorpe and Frodingham, near the River Trent (the model for the fictional Floss); it was then shipped up the Trent to the iron works and blast furnaces of Yorkshire.Footnote 45 In Eliot's novel, the telltale red dirt at the Red Deeps is both a reminder of past extraction and the clue that leads Tom Tulliver to discover his sister's secret rendezvous in the exhausted quarry with the hunchback Philip Wakem—one of two thwarted marriage plots that shape the novel's trajectory.

Maggie and Philip's relationship lacks an apparent future because of Philip's deformity and because their fathers hate each other, yet their relationship thrives in secret in the abandoned quarry, at odds with chrononormativity and repronormativity, which Elizabeth Freeman has described as the “interlocking temporal schemes necessary for genealogies of descent.”Footnote 46 This is not to say that their relationship exhibits the liberatory quality that Freeman ascribes to queer time, the release from a timescale oriented toward “maximum productivity.” Rather, their relationship operates on what I would call an extractive trajectory, diverging from temporal structures of renewal and rebirth. In rhythm with the exhaustion that haunts the Red Deeps, Maggie and Philip's relationship is denied the possibility of futurity and consummation, but it is also denied an ending or closure and seems to live on even after Maggie's dramatic death. After Maggie is swept away in the novel's climactic flood, Philip remains to haunt the Red Deeps, his grief persisting in an undead future that extends beyond the novel's penultimate line: “His great companionship was among the trees of the Red Deeps, where the buried joy seemed still to hover—like a revisiting spirit” (518). Like Nostromo, The Mill on the Floss ends with a haunted vision of extraction's remains.

The revised marriage plot that we find in provincial realist novels set in extraction zones conveys, I want to suggest, how human life and reproduction are bound up in the economies and ecologies of extraction. Philip's companionship with the trees that emerge from the “buried joy” of the Red Deeps emblematizes the operations of extraction ecologies as I have been describing them: the dynamic bundling of human, animal, and plant life with extracted commodities and the nonliving earth; the undead futures of extraction and exhaustion. Decades ago, Raymond Williams in The Country and the City highlighted marriage as a symptomatic terrain in the postpastoral novel of environmental displacement: “One of the most immediate effects of mobility, within a structure itself changing, is the difficult nature of the marriage choice. This situation keeps recurring in terms which are at once personal and social.”Footnote 47 Williams's impulse to think of marriage in socio-environmental terms anticipates those critics who are now rereading literary history with an eye to the ways that human choice is coproduced by natural circumstance. Benjamin Morgan, for example, has argued against “a conventional literary historicism that attributes causal primacy to human culture” without attention to “entanglements of human action with geological and climatological events … as motive forces of history.”Footnote 48 Morgan's argument conveys in wider terms the operations by which extraction ecologies can be said to leach into the provincial realist marriage plot in the age of industrial extraction.

Reading Maggie and Philip's thwarted marriage plot in terms of environmental circumstances diverges, to be sure, from the approach of critics like Talia Schaffer, who focuses on the history of marriage; and yet the historical shift in marriage that Schaffer charts, from familiar to romantic marriage, tracks with underlying changes in social organization such as the shift to extraction-based life. In Schaffer's reading, Maggie Tulliver is perched between two ideologies of marriage, and the novel “takes the forms of marriage that allowed people to express their yearning for a larger, richer sociality and argues that modernity is transforming them into individualizing, isolating experiences.”Footnote 49 The shift toward an individualizing, isolating modernity that Schaffer describes here is related, I would suggest, to the shift toward an extraction-based society that the novel describes—for this new society was premised on a break with the interests of future generations or, to use Schaffer's terms, a break in the bonds of kinship as they extend into the future.

The Reproduction of Extractive Labor in Jane Rutherford; or, The Miners’ Strike

Such mysterious seepage of the nonliving earth into human lives and human futures is at the very heart of Jane Rutherford; or, The Miners’ Strike (1853), a novel by Fanny Mayne that attempts to join the provincial realist marriage plot with the industrial novel's attention to labor—in this case, extractive labor. Centering on a mining village and on the necessity for the reproduction of workers within extraction economies, the novel, unlike Nostromo or The Mill on the Floss, examines the conditions of laboring life within extraction zones. This is not to say that its politics are radical: as a contemporary review in Tait's Edinburgh Magazine put it, “This is a domestic story, intended to illustrate the evils of strikes.” Despite the novel's crude political moral, however, the reviewer still finds it of interest because the writer seems “at home among” the miners, “intimate with their circumstances and condition.”Footnote 50 Joseph Kestner has also discussed Jane Rutherford’s domestic approach to the mining question, arguing that the novel conveys how the “microcosm of the patriarchal family, with its unjust distribution of power, reflects the situation of the industrial world itself.”Footnote 51 I focus instead on the novel's resistance to repronormativity in the context of an extraction economy dependent on young workers.

Before its 1854 publication, Jane Rutherford was initially serialized in Fanny Mayne's periodical The True Briton from June to October 1853. The paper was evangelical and populist in tone, and staunchly abolitionist, but not anti-establishment.Footnote 52 The journal catered to readers in mining districts with numerous articles such as “Interesting Facts Related to Minerals” (7 October 1852), “The Ventilation of Mines” (16 December 1852), and a series entitled “The Gold Hunt” (20 January 1853–21 April 1853), the last installment of which ended with a melancholy reflection on exhaustion: “The gold hunt, and all other earthly pursuits of man, will soon come to an end.”Footnote 53 Though serialized in 1853, Jane Rutherford is set in 1844 in the immediate wake of the 1842 Coal Mines Act, and it depicts the provincial coal-mining region in Somerset, supplier to the wealthy neighboring city of Bath.Footnote 54 This Somerset mirrors Conrad's Costaguana as a place that generates extracted resources for the wealth of others elsewhere. While the human drama of the novel mostly takes place aboveground, it is thoroughly interwoven with the coal deposits below, as the narrator describes in the opening pages: “where coal abounds, there also factories abound … caus[ing] the centre of labor … to teem with life.”Footnote 55 Human life teems in conjunction with extraction economies despite the ecological risks and environmental toxicities they entail.

Such risks and toxicities are everywhere in Jane Rutherford. The narrator details how the heroine's embittered father, Jonathan Rutherford, has experienced “the ordinary mischances of his calling”: “Once he was in bed for ten weeks, from hurts received in a serious explosion of fire-damp. At another time, from the compound fracture of his thigh. … One spring he got the miner's inflammation of the lungs, and was ever after ‘touched in the wind.’”Footnote 56 Cumulative risks are likewise visible in the distinct physical type that the miners present: “At first sight you know he is a miner. A sort of earthen, yellow, mole-like cast of countenance, with sunken peering eyes, a great development of bone and muscle, especially about the shoulders and hips, and legs so small that they seem scarcely to have enlarged or elongated since they left the cradle.”Footnote 57 Like goldfish that grow to the size of their bowl, miners take on the form of the mine, a result of having begun the work as young boys. In Child Workers and Industrial Health in Britain, Peter Kirby has described how nineteenth-century observers reckoned that “the physical shape of miners was fundamentally different from that of other workers” and “that colliery communities were populated by a discrete shorter genotype which was sustained by the high degree of occupation succession between male members of coalmining families in isolated mining settlements.”Footnote 58 That such a belief persisted in the nineteenth century helps explain Jane Rutherford’s interest in occupational intermarriage via the romance between Jane Rutherford, daughter of a miner, and William Norman, a millworker—for the reproduction of miners was a key component of the extraction economy in Britain.Footnote 59

Jane and William's marriage ultimately concludes Mayne's novel, but the event is serially delayed by various plot complications, deferrals of the conclusion that resemble the open time frame of exhaustion as described by Jevons and others: the threshold that recedes as we move toward it. When the marriage finally happens, it is an older, childless marriage that will produce no new workers. While this outcome in some ways mirrors those of Nostromo and The Mill on the Floss, it also serves, in a novel focused on working-class life in an extractive economy, as a staving off of tragedy, given the number of child deaths that happen in the course of the novel. In the novel's climactic accident, a miner named Abraham Pearce and his two sons, aged twelve and ten, are descending the shaft with other miners, and when the rope snaps they all die. Mayne depicts the deaths from the perspective of the miners at the top of the shaft, watching from above: “There they go, hanging to the chain like bees, each one seated on a cross stick, passed through a link in the chain. … There they go, in a moment they are out of sight of the men above ground, when Eliezer cries out, ‘The Lord ha’ mercy on their zoulz, for they are all dead men. Ztop the wheel!’ But it is too late. The rope has snapt, and all who hang in are launched into eternity!”Footnote 60 As if to establish the generational quality of this risk, the novel also flashes back to an accident in Abraham Pearce's own boyhood, when he was left in the pit for five days but survived; that moment is illustrated in figure 3, with the caption “Mrs. Pearce reproaching the colliers for leaving her son in the pit.” The Mrs. Pearce pictured here, in flashback, is Abraham Pearce's mother, but the novel also depicts his wife, the second Mrs. Pearce, mourning later for her husband and sons who have died in the pit. The recurring grief of the first and the second Mrs. Pearce conveys the cycle of human reproduction on which the exhaustion of the mine depends.

Figure 3. “Mrs. Pearce Reproaching the Colliers for Leaving Her Son in the Pit.” Illustration from The True Briton, vol. 2 (new series), no. 1 (4 August 1853): 1.

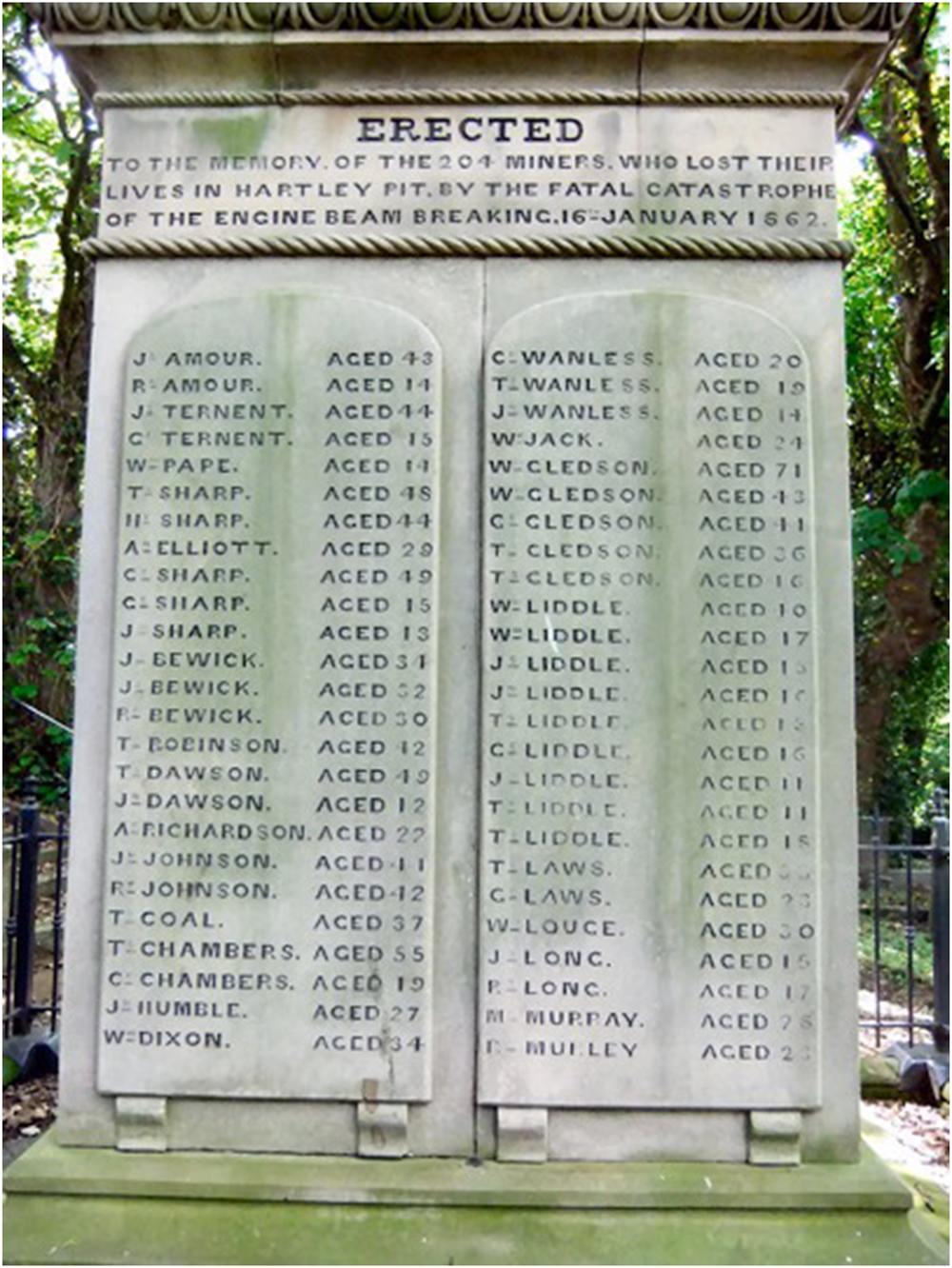

As in Jane Rutherford, Victorian mining accidents often involved boys as well as men, and father and sons frequently died together. In the 1862 Hartley Colliery disaster, one of the major mining accidents of the period, 204 men and boys were trapped underground and eventually died; one-third of the victims were under age nineteen. Newspaper accounts of the disaster emphasized how entire male lines of families were extinguished and how mothers persisted in grief afterward: “One poor woman has her husband and six sons in the pit, besides a boy whom they had adopted.”Footnote 61 As the monument to this tragedy records, such events could destroy generations of a mining family—brothers, fathers, sons—in a moment (fig. 4). The death of the child miners in Jane Rutherford could thus be said to anticipate a key feature of Anthropocene temporality, one that Rob Nixon eloquently sums up in the idea of “borrowed time”: “In this interregnum between energy regimes, we are living on borrowed time—borrowed from the past and from the future.”Footnote 62 Fossil fuels formed in the deep past, but the residue of their combustion will persist long into the future. Nixon's sense of a depleted future, of a future from which we are borrowing, shines through in all these novels’ accounts of the social ecology of extraction, just as it shines through in the memorial to the Hartley Colliery disaster with its list of victims from age ten to age seventy-one. Provincial realism shows us that the extraction economy was understood to be a future-depleting system long before scientific consensus on the climatic effects of greenhouse gases was achieved.

Figure 4. Monument in St Alban's parish churchyard, Earsdon, Tyne and Wear, to victims of the Hartley Colliery disaster, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hartley_Pit_Disaster_Monument.JPG.

Conclusion

I have argued that Nostromo, The Mill on the Floss, and Jane Rutherford, three provincial realist novels set in extraction zones, convey how provincial realism of the nineteenth-century extraction boom adapted the temporal features of the novel to account for the open horizon of exhaustion—a future untethered to past cycles, a future drained by an extraction-based present. As novelistic renderings of extraction's ecologies, they express how human lives interpenetrate the nonliving earth, and they inhabit a temporality that militates against both discrete endpoints and cyclical renewal. But if extraction's future is distressingly unmoored from the cycles of the past or the bonanza of the present, the three novels do envision what it might look like by way of their postextractive settings. In Jane Rutherford, a nearby hillside has been blazing intermittently for thirty years, burning with the combustible refuse of the coal pit; in The Mill on the Floss, Dorlcote Mill and the Guest & Co. oil mill hum along noisily, while nearby Red Deeps is retired into a “garment of Silence” (316); in Nostromo, a wild ravine of sublime beauty is transformed by the workings of the San Tomé mine into “a big trench half filled up with the refuse of excavations and tailings” (79). Such sites are conventionally called sacrifice zones, yet all these novels belie the logic that the term “sacrifice” implies, which is also the logic of extraction: the idea that one part can be forfeited without affecting the whole. The three novels convey instead how extraction ecologies leach into human marriage, growth, and reproduction, defying the account of the natural world that inheres in extractivism. They point ahead to the unintended consequences of nineteenth-century extraction, the dynamic, open webs of causation in which we are still enmeshed today.