A number of national medical boards are moving towards using ‘competency’ as a framework for assessment of trainee doctors: the USA, Canada, The Netherlands and Australia, to name a few. Reference Norcini and Burch1–Reference Scheele, Teunissen, Van Luijk, Heineman, Fluit and Mulder3 In the UK the trainee assessment process has changed as part of bigger modifications in the structure and organisation of postgraduate medical education. Reference Palmer and Devitt4 Previously, the Record of In-Training Assessment was an annual method of assessing specialist registrars in the UK. Reference Delamothe5 It involved a face-to-face meeting between the trainee and the assessors; prior to this meeting a report from the trainer or educational supervisor on the knowledge and skills acquired by the trainee during the previous 12 months, and a summary of achievements compiled by the trainee, were submitted to the assessors. In June 2007 the four UK Health Departments published A Reference Guide for Postgraduate Specialty Training in the UK (the ‘Gold Guide’); Reference Bache, Brown and Graham6 this has been updated on an annual basis since then, the last one being published in 2009. Section 7 of the guide describes the Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP), a formal framework to review the evidence of progress of every doctor in training. The Gold Guide directs that doctors in training should now be called ‘specialty trainees’ (ST1–6, based on their year of training). Specialty trainee doctors are now expected to collect formative and summative assessments during the training year and submit them annually in the form of a portfolio to the ARCP panel. Additional documentation might be provided as evidence of achievement of competency for consideration by the panel.

Attempts have been made to standardise various summative and formative competency assessment tools, also called workplace-based assessments (WPBA), such as the mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise, Directly Observed Procedural Skills and Multisource Feedback, in various specialties. 7 The Royal College of Psychiatrists has designed and commissioned its own WPBAs: the Assessment of Clinical Expertise, the mini Assessed Clinical Encounter, Case-based Discussion and the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire. Reference Wilkinson, Crossley, Wragg, Mills, Cowan and Wade8 These have been rolled out over 3 years (2006–8). These WPBAs allow senior medical and non-medical staff to assess trainee psychiatrists on various clinical domains. Guidance for assessors has been made available on the College's website. The College has also delivered a number of ‘train the trainers’ programmes all over the UK in the past few years. The College has also published a guide giving details of the minimum number of WPBAs required towards an individual trainee's ARCP evidence. Reference Brittlebank, Bhugra, Malik and Brown9

The Royal College of Psychiatrists had (in 2007 to early 2008) contracted an external organisation, Healthcare Assessment and Training (HcAT), a non-profit making organisation, for the recording and storage of WPBAs electronically. Trainee psychiatrists were asked to use the HcAT website for collation of WPBAs and to submit paper copies of the WPBA to the ARCP panel in the portfolio. From late 2008 onwards the College commissioned its own electronic portal, Assessment Online (https://training.rcpsych.ac.uk). In early 2009 the Northern Deanery school of psychiatry produced a document for the trainees to use as a guide for collecting and presenting evidence in a particular format for the ARCP portfolio (available from the authors on request). The ARCP has now been completed on two occasions in various deaneries in England in 2008 and 2009. Two of the authors (A.V. and P.T.) went through the ARCP in 2008, and having perceived difficulties during this process speculated if other trainees in the deanery had undergone similar experiences. The aim of the survey was to collect feedback from specialty trainee psychiatrists regarding their experience and perception of the ARCP process. Two annual surveys were conducted to estimate differences, if any, between the two years.

Method

The questionnaire items were devised by two authors (A.V. and P.T.). The items were discussed with the third author (K.V.) and modified. A pilot was conducted on three trainees and the items were further changed based on their feedback. The questionnaire items included categorical and Likert scale questions; free text comments were invited. These were then uploaded to the Surveymonkey website (www.surveymonkey.com). This website enabled collation as well as summative analysis of the results. All specialty trainees (ST1–5) who had undergone the ARCP were contacted by email on behalf of the authors by the deanery's specialty training programme coordinator within a week of the completion of their annual reviews. They were invited to participate in the survey by means of a hyperlink within the text of the email. By clicking on the link they were directed to a webpage presenting the questionnaire. One reminder was sent 2 weeks later to all the trainees to encourage them to complete the survey. The surveys were closed 1 month after the first email was sent (in June 2008 and June 2009).

The results of the first survey were presented at the authors' host National Health Service Trust (Northumberland Tyne and Wear) medical education committee and the Northern Deanery school of psychiatry. The results were also presented at the national Annual Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Conference in 2008. Clearance was gained from the host trust prior to initiation of the survey.

Results

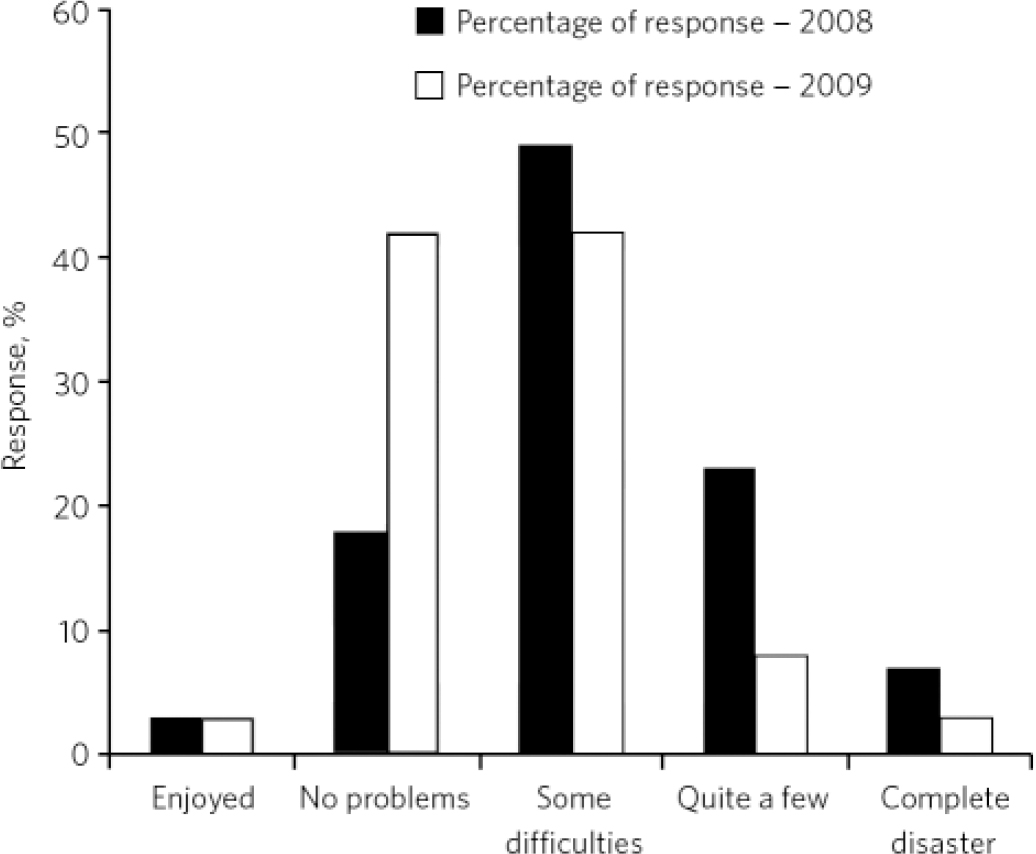

The survey included all the psychiatry trainees in the Northern Deanery in two successive years. The response rates to the survey were the same over the 2 years: 63% each in 2008 and 2009 (Table 1). We observed a significant improvement in trainees' perception of the ARCP on most of the parameters over the period (Table 2). Overall, 21% of the trainees faced no problem through the ARCP process in 2008, whereas 45% had no problem in 2009 (Fig. 1). In 2008, 48% of the trainees felt they did not have adequate prior information about the process of ARCP; this improved to 28% in 2009. Individual comments in 2008 referred to inadequate and late information provided by the Royal College of Psychiatrists on the required content and structure of the portfolio. Some trainees felt that the curriculum was far too complex and off-putting. In the second survey (2009), the trainees felt there was too much replication of information, which had to be repeated on different forms. Some trainees were also not sure which evidence was essential for the portfolio besides WPBAs.

Fig 1 Overall satisfaction with the process.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the sample

| Training year | Trainee response in 2008 n (%)a | Trainee response in 2009 n (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| ST1 | 13 (25) | 13 (23) |

| ST2 | 12 (23) | 16 (29) |

| ST3 | 16 (26) | 12 (16) |

| ST4 | 17 (20) | 9 (10) |

| ST5 | 0 (0) | 12 (18) |

Table 2 Survey items

| Trainees agreeing with statement, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | χ2 | d.f. | P | |

| Adequate information about the ARCP | 52 | 72 | 8.5 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Difficulties in collecting evidence | 93 | 78 | 9.1 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Non-availability of a list of acceptable evidence for the purpose of the portfolio | 75 | 22 | 56.2 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Inadequate number of assessors to complete WPBA | 42 | 25 | 6.5 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Difficulty in getting colleagues to complete assessments on time | 69 | 45 | 11.7 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Assessor unsure about expected competency at stage of training | 56 | 45 | 2.4 | 1 | 0.12 |

| Assessor found form too basic | 14 | 3 | 7.8 | 1 | 0.005 |

| Assessor found form too complicated | 29 | 17 | 4.1 | 1 | 0.043 |

| Assessor unsure about which WPBA tool to use for a clinical situation | 29 | 17 | 4.1 | 1 | 0.043 |

| Assessor found own training affecting ability to assess trainee | 36 | 15 | 11.6 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Assessor reluctant or unable to complete electronic form of WPBA | 31 | 18 | 4.6 | 1 | 0.032 |

| Access difficulties to electronic portal | 73 | 28 | 40.5 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Inadequate timing of ARCP | 26 | 25 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.872 |

| Inadequate preparation time | 19 | 18 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.855 |

In total, 93% of the respondents in 2008 and 78% in 2009 experienced various difficulties in gathering evidence. Non-availability of a list of acceptable evidence for the purpose of the portfolio was highlighted by a majority (75%) of the trainees in 2008. In the 2009 survey, 45% of trainees found difficulties in getting colleagues to complete assessments on time (compared with 69% in 2008, P<0.001) and 45% felt that their assessor was unsure about their expected competency at the stage of their training (not significantly different from the 2008 response of 56%). In both surveys there were a number of comments regarding the Assessment of Clinical Expertise being time-consuming and trainees finding it difficult to persuade their consultant supervisors to devote at least an hour of their clinical time to completing it. The majority of respondents (81% in 2008 and 82% in 2009) felt that they had adequate time for preparation of their portfolio and they felt that the timing of ARCP was convenient (74% in 2008 and 75% in 2009). However, the process of maintaining portfolios was considered cumbersome by some trainees. It was observed that the process of collating WPBAs impinged on the clinical training time as well as the preparation time needed for the MRCPsych examinations. Some individuals commented that the ARCP clashed with MRCPsych examinations; others stated that the ARCP was too close to midterm reviews and thus affected their ability to prepare adequately for their ARCP. Some trainees felt disheartened by the lack of feedback subsequent to the ARCP, as they had received either none or a sheet of paper with a tick-box stating that they had passed the assessment. Some felt that if the content and structure of a portfolio had been exemplary, this should be commented upon by the assessors and further encouraged.

Discussion

So far as we are aware this is the first survey that has attempted to collate trainees' perceptions of the new method of assessing trainee doctors in the UK. The results of the study validated our hypothesis that some or most of the trainees might have faced varying levels of difficulties during the process. The trainees have, however, noted a significant improvement in the process of ARCP over 1 year. It is also possible that the trainees have adapted to the new competency-based assessment process over this time.

One of the themes that emerged from the results was that trainees would have benefited from better guidance through the process in 2008. This should have included explicit information on the structure and format of the portfolio. A previous study has highlighted that there needs to be consistency in content of portfolios. 10 More published guidance about WPBA and the ARCP process was made available in 2009, including a College Occasional Paper. Reference Colbert, Ownby and Butler11 The College's replacement for the HcAT system, Assessments Online, seems to have worked better; only 28% of the trainees had access difficulties in 2009 compared with 73% in 2008.

In other pilot studies, trainees have found the process of gathering evidence time-consuming and frustrating owing to the unavailability or unwillingness of potential assessors. Reference Wilkinson, Crossley, Wragg, Mills, Cowan and Wade8 Many respondents in our survey raised concerns that their assessors lacked the knowledge and skills necessary to assess them using WPBAs. Such problems have been perceived in other countries too and it is recognised that adequate training of the trainers is crucial for success of the assessment process. Reference Norcini and Burch1 Our survey highlighted that non-medical staff were reluctant and found it harder to judge whether individual trainees had reached their expected level of competency for a particular domain. This again raises the issue of training of the assessors, and whether there are ways to validate and standardise assessments by non-medical staff.

The timing of ARCP needs to be carefully planned. Attempts may have to be made to individualise ARCP dates so as to avoid clashes with midterm reviews and MRCPsych examinations. Also, having the ARCP much before the end of the training year might not give a true reflection of the competency of the trainee. It might be encouraging for the trainees to receive an explicit feedback on their performance during or after the ARCP.

Limitations

The surveys were limited to the Northern Deanery; however, the ARCP process is a national one and trainees in other deaneries might have perceived similar difficulties, as the guidance and structure around the process are comparable. The surveys were conducted just after the ARCP and hence there might have been some ‘knee-jerk’ responses to the questionnaire. Our survey was designed to evaluate the ARCP process by measuring trainee satisfaction; it was not designed to be a qualitative study. The usefulness and validity of surveys are generally limited by the level of motivation and interest shown by the responders. It is possible that the results of this survey reflect the views of responders who had either mostly a positive or negative perception of the ARCP process or who were motivated to respond.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.