A growing literature maps the presence of women in elected assemblies across different levels of government. The majority of contributions finds female candidates to be most successful at the lowest echelons, hypothesizing that local governments are either more appealing or easier to reach for women (Blais and Gidengil Reference Blais and Gidengil1991; Brodie Reference Brodie1985; Darcy et al. Reference Darcy, Welch and Clark1994; European Commission 2009; Ford and Dolan Reference Ford and Dolan1999; Gavan-Koop and Smith Reference Gavan-Koop and Smith2008; Kjaer Reference Kjaer2011; Maille Reference Maille1994; Matland and Studlar Reference Matland and Studlar1998; Norris Reference Norris1993; Stokes Reference Stokes2005; Trimble Reference Trimble1995; Vengroff et al. Reference Vengroff, Greevey and Krisch2000). The pattern of female representation in countries such as the United States and Canada forms a pyramidal shape, whereby women are scarcest at the highest strata. However, a number of more recent studies find empirical evidence for the reverse pattern in countries such as Germany and Australia, namely that women are most successful at the highest levels of government (Eder et al. Reference Eder, Fortin-Rittberger and Kröber2016; Hashimoto Reference Hashimoto2001; Henig and Henig Reference Henig and Henig2001; Kjaer Reference Kjaer2011; Ortbals et al. Reference Ortbals, Rincker and Montoya2012). Until now, contributors have focused solely on putting forward explanations for the pyramid or the reverse shape. This article argues that existing research on local–national gender gaps overlooks a crucial factor: the different party system constellations across levels of government.

Drawing on a new data set (Eder and Fortin-Rittberger Reference Eder and Fortin-Rittberger2017) mapping the representation of women at all four echelons of government in Germany, from the national and state level down to the local levels of districts and municipalities from 2000 to 2013, we show that the electoral performance of left-wing and minor parties differs considerably across levels of government in Germany, which in turn affects women’s electoral fortunes.Footnote 1 While left-wing parties hold on average more than half of the seats at the higher levels in Germany – the Bundestag and state assemblies – they are less successful at the local administrative levels. Instead, minor parties and independent candidates win a considerable seat share, but are mostly absent in the Bundestag. We find that differences in the constellation of parties on the left–right ideological scale are closely paralleled by the shares of female office-holders across different levels of government in Germany. These findings add an important piece to the complex puzzle of female representation across different levels of government and offer a potential clue as to why local–national patterns of women’s representation assume various shapes in different countries.

EXPLANING THE LOCAL–NATIONAL GENDER GAP

For a long time, researchers took it for granted that women are more likely to be elected to municipal than national or state assemblies, because barriers to entry in local politics are assumed to be lower. Electoral contests at the local level are considered by some to be less fierce because election campaigns are both less competitive and less time- and resource-demanding than at the national level (Gavan-Koop and Smith Reference Gavan-Koop and Smith2008; Gidengil and Vengroff Reference Gidengil and Vengroff1997; Henig and Henig Reference Henig and Henig2001; Kushner et al. Reference Kushner, Siegal and Stanwick1997). In addition, issue affinity could motivate candidates: many policy fields relevant to local governments are held to be closer to women’s traditional spheres of competence and interest (Huddy and Terkilsen Reference Huddy and Terkilsen1993; Shaul Reference Shaul1982). In a nutshell, women are ‘more likely to run for and win offices that are seen as lower prestige and more secretarial in nature than offices that are perceived as having a higher level of responsibility’ (Crowder-Meyer et al. Reference Crowder-Meyer, Kushner Gadarian and Trounstine2015: 321).

In contrast to the studies suggesting that women’s representation dons a pyramidal shape, more recent contributions have found the pyramid to be turned on its head in some countries: Christina Eder et al. (Reference Eder, Fortin-Rittberger and Kröber2016) show that, in Germany, women are more successful in national and state elections than in district elections. A handful of comparative analyses revealed a similar pattern for some European countries (Henig and Henig Reference Henig and Henig2001; Ortbals et al. Reference Ortbals, Rincker and Montoya2012) and Australia (Irwin Reference Irwin2001), as well as Asian countries (Hashimoto Reference Hashimoto2001), while others found no clear relationship at all between levels of government and representation (e.g. Drage Reference Drage2001; Tolley Reference Tolley2011).

So far, three potential rationales have been put forward to account for the higher share of women in national parliaments as compared to local councils, hinging on both demand- and supply-side mechanisms. On the supply side, holding political office is said to be more attractive for women at the national than at the local level due to the higher degree of professionalization of national office (Kjaer Reference Kjaer2011). Women still perform the bulk of domestic tasks in households while at the same time participating in the labour force (Chhibber Reference Chhibber2002; Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Kunovich and Hughes2007). Commitment to local politics thus adds another unpaid duty to the double burden of paid work and household, whereas holding an office at the national level is a remunerated profession.

On the demand side, recruitment patterns vary across levels of government. The more institutionalized the nomination process is, the easier it should be for outsiders – such as women – to learn the rules of the game and be successful (Caul Reference Caul1999; Childs and Kittilson Reference Childs and Kittilson2016; Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2006; Henig and Henig Reference Henig and Henig2001; Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris1993). At the national and state levels of government, political parties control recruitment procedures tightly and conduct their search for candidates according to their legally established principles. By contrast, in local elections, ‘old boys’ networks’ tend to be more decisive in nomination processes (Holtkamp Reference Holtkamp2007; Holtkamp et al. Reference Holtkamp, Wiechmann and Schnittke2009; Pini and McDonald Reference Pini and McDonald2011).

The third and last explanation hinges on quotas. While party-based gender quotas generally lead to increases in the proportion of female office-holders (Caul Kittilson Reference Caul Kittilson2006; McKay Reference McKay2004), research shows that compliance with voluntary party quotas varies across levels of government. Because parties adhere more rigorously to their quotas in federal and state elections than at the lower echelons, the combination of differentiated compliance with the shortage of willing female candidates at the local level reinforces the local–national gender gap (Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2006, Reference Davidson-Schmich2016).

Women’s representation in elected office in Germany, which is the case we analyse in more detail in this article, indeed displays an inverse pyramid shape. Figure 1 is based on our original data set on women’s representation across the four levels of government and illustrates that the national and state levels have the highest proportions of women, while assemblies at the district and municipal levels display a significantly smaller seat share of female office-holders. District assemblies under-represent women the most with on average 1.5 per cent fewer female legislators than the municipalities.Footnote 2 Thus, there is a national-state vs. district-municipalities gap with 10 percentage points fewer women at the lower echelons.

Figure 1 Percentage of Women Representatives at Different Levels of Government (2000–13) Notes: 95 per cent confidence intervals. Cases selected on election years only. National: 3 cases, state: 47 cases, district: 700 cases, municipality: 3,559 cases.

There are hence two competing sets of studies that suggest either a pyramid-shaped pattern with more female office-holders in local than national assemblies, or a pyramid turned on its head, with only a few women at the lowest echelon. The arguments outlined in this section have limited explanatory power to account for between-country variations, but rather rely on different factors to illuminate the pattern. This hints at a missing piece in the puzzle of female representation. As we argue in the following section, we believe that variation in party system constellations across levels of government can account for different patterns of women’s representation.

THE MISSING LINK: INTER-LEVEL VARIATION OF PARTY SYSTEMS

Previous research identified the strength of left-wing parties, the effective number of parliamentary parties, district magnitude and party size as key features explaining the variation in women’s representation across countries (Caul Reference Caul2001; Kenworthy and Malami Reference Kenworthy and Malami1999; Matland and Studlar Reference Matland and Studlar1996; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Salmond Reference Salmond2006). The basic logic implies that the ideological orientation of the major parties and the competitiveness of the party system determine the level of demand for female candidacy and thereby office-holders. Despite the crucial insight this set of literature offers, these studies consider party systems as nationally uniform features, and thus ignore the high degree of within-country variation.

The scholarship on political parties has established that party systems often differ considerably between the local, regional and national levels of government in multilevel systems (De Winter Reference De Winter2006; Kenny and Verge Reference Kenny and Verge2013; Wolinetz and Carty Reference Wolinetz and Carty2006). Germany is no exception to this rule: particularly since reunification, party systems vary noticeably within as well as across echelons (Sturm Reference Sturm1999). The five major German political parties, namely the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), the Social Democrats (SPD), the Liberals (FDP), the Greens and the Left party which gained seats in the federal parliament in the last few general elections, each have their regional strongholds. Well-known differences are that in the former GDR states, the Left party is rather successful, while it receives few votes in the Western states. The Social Democrats traditionally performed best in highly industrialized areas, and the Christian Social Democrats (CSU) are the sister party of the Christian Democrats that operates exclusively in Bavaria.

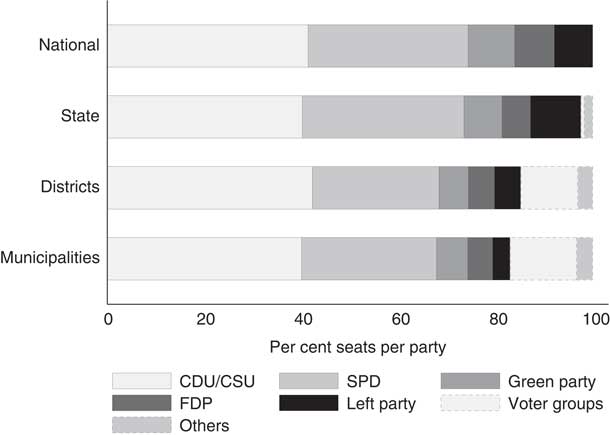

Figure 2 displays the seat share of parties at each of the four German levels of state from 2000 to 2013 and illustrates differences in the party system across levels of government. Minor parties are most prevalent at lower levels while being practically absent in higher echelons.Footnote 3 The five major parties, however, held on average 97.2 per cent of the seats in state parliaments from 2000 to 2013, but only about 85 per cent at the lower echelons. Our figures corroborate Björn Egner and Max-Christopher Krapp’s (Reference Egner and Krapp2013) findings that (loose) voter associations and independent candidates are most successful in local elections. Beyond, we find that this negative correlation between the level of government and the seat share of minor parties exists in all 16 states, with the exception of the three city-states, Hamburg, Bremen and Berlin.Footnote 4

Figure 2 Seat Share of Parties at Different Levels of Government (2000–13) Note: National: 3 cases, state: 47 cases, district: 700 cases, municipality: 3,559 cases.

In addition, Figure 2 suggests that the success of minor parties comes mostly at the expense of Germany’s three most important left-wing parties the SPD, the Greens and the Left party, while the CDU/CSU and the FDP secure a more or less equal share of seats across all levels of government. The local–national gap between the mandates won at the highest and the lowest level of government from 2000 to 2013 was on average 12.9 per cent for the SPD, 3.9 per cent for the Left party and 3.0 per cent for the Green party. Again, this pattern exists in most German states, apart from Hamburg and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.Footnote 5

We argue that both the weaker performance of the three left-wing parties as well as the larger seat share won by minor parties provide compelling explanations for the under-representation of women at the municipal and district level. Firstly, women might be less likely to win seats at the lower echelons because of the lower proportion of seats won by left-wing parties. Previous research finds that the strength of left-wing parties has a beneficial impact on the level of women’s representation at the national (Caul Reference Caul1999) as well as at the local level (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999; Rincker Reference Rincker2009; Sundström and Stockemer Reference Sundström and Stockemer2015) or the European Parliament (Lühiste and Kenny Reference Lühiste and Kenny2016; Fortin-Rittberger and Rittberger Reference Fortin-Rittberger and Rittberger2015). Social democrats, socialist and green parties are predisposed to promote female candidacies as it is their explicit aim to represent all societal groups (Caul Reference Caul1999; Jenson Reference Jenson1995; Krook and Childs Reference Krook and Childs2010). Furthermore, these parties are more inclined to commit to gender equality by adopting voluntary quotas (if there are no mandatory ones, as is the case in Germany) (Caul Reference Caul2001; Verge Reference Verge2013).Footnote 6 If left-wing parties indeed supply the lion’s share of women representatives at all levels of government, their weaker performance at the lowest echelons provides an additional impediment to the election of women. Thus, we hypothesize the positive relationship between the seat share of left-wing parties and the proportion of women in assemblies holds for all levels of government.

Hypothesis 1: The higher the proportion of seats for left-wing parties, the higher the share of female representatives in an assembly, no matter the level of government.

Secondly, the increased presence of minor parties, such as regional parties, issue lists and independent candidates, could further reduce the proportion of women in local legislatures. Small parties, especially those focused around narrow issues, should be less inclined to introduce and apply gender quotas. Previous studies on gender quotas showed that, due to public attention, large parties are more likely to conform to self-imposed quotas (like those we observe in Germany), at least in the higher echelons (Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2016; Magin Reference Magin2011). Correspondingly, small parties who only run or succeed at the lower echelons feel less public pressure to introduce or apply rules for gender-balanced lists. Furthermore, minor parties tend to have no women’s organizations which could advocate such measures within the party (Leyenaar Reference Leyenaar2013: 178).

Thirdly, incentives to balance tickets in the absence of quotas are also smaller for minor parties. From research on national elections we know that parties recruit female candidates to attract a broader range of voters (Matland Reference Matland1999). However, electorates at the local level are often more homogenous, particularly in smaller localities, and for this reason we conjecture that parties in such settings face fewer incentives to balance their tickets. Furthermore, local electorates could be more concerned about single issues and particular policy positions than gender equality or other larger ideological concerns when making a vote choice: specific policies are more decisive for local-level elections than ideological orientations (Egner and Krapp Reference Egner and Krapp2013). Minor parties may therefore expect only a few additional votes for balancing tickets and are thus less likely to invest time and resources into the recruitment of female candidates.Footnote 7

Lastly, the distance between voters and representatives is smallest at the local level, rendering characteristics such as reputation and name recognition more important. Groups such as the Free Voters (Freie Wähler) often nominate local notables (Wehling Reference Wehling2007), and these candidates tend to be male rather than female. In sum, we expect the proportion of women in an assembly to decrease as the seat share of minor parties increases, and thus, formulate our second hypothesis as:

Hypothesis 2: The higher the proportion of seats for minor parties, the smaller the share of female representatives in an assembly, irrespective of the level of government.

DATA AND ANALYTICAL STRATEGY

For the purposes of this article, we make use of a new and comprehensive set of data mapping the representation of women at the national, state, district and municipal levels of government in Germany over time (Eder and Fortin-Rittberger Reference Eder and Fortin-Rittberger2017). Our data collection on the composition of assemblies encompasses three federal elections, 68 state elections, 1,023 district elections and 3,564 municipal elections from 2000 to 2013.Footnote 8 For all observations we documented the absolute and relative number of women in the respective assembly as well as the absolute and relative number of women by party. This data collection is by far the most comprehensive to date, mapping the composition of elected assemblies in Germany. Our article is therefore the first to propose an investigation of the presence of women across all four levels of government in Germany.

The dependent variable used in all analyses is the percentage of women represented in the elected bodies. As main independent variables, we focus on the seat shares of left-wing and minor parties, whereby left-wing parties represent the SPD, the Greens and the Left party, while voter groups, independent candidates and others are subsumed under the label minor parties.

Following previous research, we include a number of factors related to the electoral system and the socioeconomic context as control variables. We consider the level of party competition, measured in terms of the effective number of parties (Laakso and Taagepera Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979), because more competitive party systems (those with a rather large seat share for minor parties) provide easier access for female candidates (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2001).Footnote 9 Given the large literature on the beneficial effects of proportional representation (PR) on female and minority representation (for a review of main contributions see Norris Reference Norris2004), we take into account whether elections are held under PR or a mixed electoral formula.Footnote 10 Since the electoral laws for districts and municipalities are subordinated to the state level, there is a single electoral system on the local echelon valid for all districts and municipalities within the same state. The variable is coded binary, taking the value of 1 for PR and 0 for mixed member proportional systems.Footnote 11

Next, district magnitude is a common factor invoked in research on levels of women’s representation in advanced industrialized democracies (Salmond Reference Salmond2006). Because district and municipal elections take place in single districts, we use assembly size and the effective number of parties (ENP) as proxy variables. We expect to find more women in larger assemblies: the probabilities for under-represented groups to be nominated should be higher as the incentives to balance tickets increase. Beyond this, the larger an assembly, the larger the party magnitude, which in turn lessens competition for list positions (Matland Reference Matland1993: 742). Following Salmond (Reference Salmond2006), we correct for the skewed distribution of this variable by using the natural logarithm of the number of seats in each assembly.

In addition, we conjecture that a large number of voters holding post-materialist values should lead to a higher proportion of left-wing party votes (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Reingold and Owens2011) as well as to more female representatives (Magin Reference Magin2010b). Further, urban environments, featuring improved childcare facilities as well as job opportunities, should facilitate female political engagement (Andersen and Cook Reference Andersen and Cook1985; Carbert Reference Carbert2009; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003; Kolinsky Reference Kolinsky1989; Matland and Studlar Reference Matland and Studlar1998; Moncrief and Thompson Reference Moncrief and Thompson1991). As highly populated entities tend to be more urban and modern at the same time, we operationalize both post-materialist values as well as urban environment through population density.

Finally, we consider the historical context, in the present case the East–West divide. Like many other communist and socialist countries, Eastern Germany experienced comparably high shares of female representatives in the national parliament of the GDR. Yet, the numbers dropped dramatically in the first and only free elections in 1990 (Magin Reference Magin2010b) and we expect to find lower numbers of female representatives in the Eastern part of Germany than in the West (Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2006; Lemke Reference Lemke1994). To operationalize this historical context, we introduce a dummy taking the value of 1 if the entity belongs to the Eastern part and the value of 0 otherwise.Footnote 12

INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF PARTY SYSTEM CONSTELLATIONS IN GERMANY

As outlined above, we argue that variations in the proportion of female representatives across levels of government in Germany are shaped by the different party systems. To test the influence of these dynamics, we conduct our analyses in two steps. First, we examine party system effects on women’s representation for each level of government separately to explore intra-level variation.Footnote 13 Afterwards, we make use of pooled models encompassing all echelons that show the extent to which party system variations drive the pattern of women’s representation across levels in Germany. All models are OLS regressions with robust clustered standard errors at the state level to address the nested nature of our observations.Footnote 14

Table 1 investigates the effects of party strength on women’s representation through models regressing the percentage of seats held by party types on the share of female representatives at each level of government. All three models confirm our expectation that left-wing parties send more women to elected assemblies at any level of government than other types of parties. If left-wing parties win 10 per cent more seats in an election, the proportion of women increases by 2.0 percentage points at the state level, by 1.7 percentage points at the district level, and by 0.3 percentage points at the municipal level.Footnote 15 In short, if left-wing parties win five additional seats at the state and district level, on average one of these seats will be occupied by a woman. At the municipal level, on average only one in 30 additional representatives from left-wing parties is female. The positive impact of left-wing parties on women’s representation is thus much smaller at the municipal level than at the state and district levels. This suggests that left-wing parties either recruit fewer women or that their supply of women willing to run for office is considerably smaller at the local level of government than at the higher echelons. Furthermore, an increasing seat share for minor parties goes hand in hand with fewer women in assemblies at all levels of government when compared with the CDU/CSU and FDP. Although the coefficients do not reach conventional levels of significance, 10 per cent additional seats for minor parties would decrease the proportion of women in state assemblies by about 0.4 percentage points, 1.3 percentage points in district assemblies and 0.4 percentage points in municipal assemblies.

Table 1 The Effect of Left-wing and Minor Parties on the Percentage of Women at Different Levels of Government

Notes: *p<0.10; **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Looking at institutional and structural controls, we observe that most of the explanatory factors perform as expected. Larger effective numbers of parties lead to more women in municipal assemblies, while a proportional electoral system has the expected positive effect on women’s representation at the state and municipal levels. Larger legislatures contain more women at the lower echelons only. This suggests that more competitive and permissive electoral systems favour women’s representation, albeit not necessarily on all levels of government. An increasing population density, which is associated with urban areas, better childcare facilities as well as more post-material societal values, seems to improve women’s representation solely at the municipal level. As hypothesized, assemblies in the region of the former GDR feature fewer women at the lower echelons.

The overall explained linear variance of Models 1–3 in Table 1 decreases as we go from states down to the districts and the municipalities: Our series of models explains more than one third of the linear variation in women’s representation at the state level (35.3 per cent), but only about one quarter at the district (28.3 per cent) and one fifth at the municipal level (20.2 per cent). The decreasing model fit, and differentiated effects of our variables of interest across different echelons indicate that there might be level-specific factors at work that are not part of the models. Yet, the fact that the covariates for left-wing parties remain stable despite the addition of many control variables yields confidence in the finding that variations in party systems matter for patterns of women’s representation across echelons.

To account for some of these level-specific factors, we produced pooled models for all administrative echelons, including interaction terms for the level of government and the strength of left-wing parties (Models 4 and 5 in Table 2) and minor parties (Models 6 and 7 in Table 2). This allows us to demonstrate that the variation in party systems across levels of government is a powerful explanation for why the pyramid of female representation is turned on its head in Germany.

Table 2 The Effect of Left-wing Parties and Minor Parties on the Percentage of Women on Different Levels of Government (with changing reference categories for the level of government)

Notes: Models using the reference category ‘state’ omitted from table. *p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01. Table 2 in the online appendix presents further robustness tests for these models.

Looking at Models 4 and 5 modelling the effects of the percentage of left-wing party seats held in assemblies, the base terms for each level dummy reveal interesting patterns. Despite the large number of control variables, the proportion of women in assemblies is lowest at the district level when we use the municipal level as a reference category (Model 5): district assemblies feature 8.8 per cent fewer women than municipal assemblies, even in the hypothetical situation where left-wing parties do not win a single seat. At the district level, the positive effect of left-wing parties is also much stronger: 10 per cent additional seats for the SPD, the Greens and the Left party lead to 1.9 per cent more women at the district level, but only to 0.5 and 0.4 per cent more women at the municipal and state level, respectively.Footnote 16

We illustrate the predictive margins of levels of government on female representation by left-wing parties in Figure 3. While larger seat shares for left-wing parties improve women’s representation on all levels of government, intercepts and slopes vary considerably. In a situation with no left-wing party represented in an assembly, we would forecast the proportion of women to be highest at the state level, followed closely by the municipal level, while the district level would only feature a marginal share of female legislators. Yet, despite this rather low point of departure, the slope for the district level is steepest, indicating that the positive impact of left-wing parties on women’s representation is particularly strong at this level.

Figure 3 Prediction of Female Representation by Left-wing Parties at Different Levels of Government

In sum, we find ample support for our first hypothesis that the success of left-wing parties explains a non-negligible part of the variation in the representation of women across levels of government and bears the potential to improve our understanding of women’s representation in Germany and beyond. If left-wing parties performed equally well across all echelons and captured about half the seats in all the assemblies – rather than 52.1 per cent of the seats at the state, 38.2 per cent at the district, and 30.5 per cent at the municipal level during the 2000s (Figure 2) – the gap in women’s representation between the levels of government would decrease substantially, albeit not entirely.

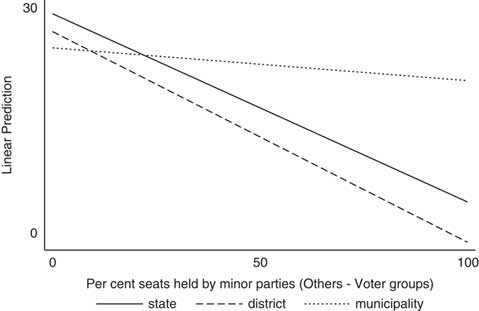

Turning to the influence of minor parties, we again observe considerable variation in the effects party systems exert across levels of government. Model 6, using the district level as a reference category, shows that for every 10 per cent of seats won by minor parties, the proportion of women decreases by about 2.4 per cent. In comparison, the same effect leads to 2.1 per cent fewer women at the state level and 0.4 per cent fewer women at the municipal level. These patterns offer support for our second hypothesis, according to which minor parties have a negative impact on female representation. However, we must also underline that the effects do not carry the same explanatory power across echelons as was the case for left-wing parties.

The predictive margins of the effect of minor parties on women’s representation are displayed in Figure 4 and point in the expected direction. Assemblies with no minor parties – no matter which administrative level is considered – feature 20 to 30 per cent women, yet for each additional 1 per cent of seats won by these parties, the proportion of women drops sharply for state and district assemblies. While negative as well, the effect of minor parties at the municipal level is much weaker than on the higher echelons.

Figure 4 Prediction of Female Representation by Minor Parties at Different Levels of Government

CONCLUSION

Mounting empirical evidence documents the existence of two distinct patterns of women’s representation across levels of government – a pyramid and an upside-down pyramid – for which researchers have not yet provided consistent interpretations. Drawing on a unique data set that maps the share of female legislators and parties in Germany, from the federal and state level down to the local levels of districts and municipalities from 2000 to 2013, this article puts forward an explanation for these contradictory patterns that has been largely overlooked in the well-established mix of institutional and sociodemographic variables researchers have investigated to date: the ideological constellation of the party system at different levels of government.

We put forward the hypothesis that differences in party systems inside a country, in particular the strength of left-wing and minor parties across government echelons, produce variations in the share of female legislators in elected assemblies. Our analyses demonstrate that as the proportion of seats for the SPD, the Green and the Left party increases, women win more mandates. As left-wing parties win on average fewer seats at the lower echelons in Germany, the assemblies at the district and municipal level consequently feature considerably fewer women. Moreover, women’s representation decreases in environments where minor parties like voter groups or independent candidates are strongest, and these types of political formations are most relevant in local politics. In sum, the weak left-wing parties and strong minor parties at the lowest echelons depress women’s representation at these levels of government in Germany and spin the pyramid of representation on its head.

Although the analyses we present focus on Germany, variations in the party system constellation have the potential to account for the inconsistent patterns of women’s representation researchers have observed in democracies: for instance, there is a higher share of women at lower levels of government than in state legislatures in Italy, Poland and Japan (Hashimoto Reference Hashimoto2001; Henig and Henig Reference Henig and Henig2001; Irwin Reference Irwin2001; Ortbals et al. Reference Ortbals, Rincker and Montoya2012). However, the opposite pattern is observed in the United States and Canada, where the share of women is highest at the local level (Kjaer Reference Kjaer2011; Tolley Reference Tolley2011). Our findings open up several avenues for future research, one of which would be to assess the relevance of differences in the party systems in a cross-country comparison in order to further establish the generalization potential of our results.

Our findings further suggest that whether, and how, parties consider gender-balanced ticketing in their recruitment and nomination process is consequential for women’s candidacies at all levels of government, which is in line with recent studies comparing the European Parliament to national assemblies (Fortin-Rittberger and Rittberger Reference Fortin-Rittberger and Rittberger2015; Lühiste and Kenny Reference Lühiste and Kenny2016). Left-wing parties seem to contribute the largest share of women in parliaments and assemblies at all echelons, while minor parties in particular, but also conservative and right-wing parties, often tend to eschew the topic of female candidacies. Fine-grained analyses of recruitment patterns could therefore help clarify the causal link explaining why left-wing parties are so important for women’s representation, even at the lowest echelons, where factors such as quotas lose some of their potency.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Fritz-Thyssen-Stiftung (grant AZ 20.14.0.003).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view the supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2017.30