I. Introduction

Human rights due diligence (HRDD) has become an essential and widely recognised tool for companies to identify and address human rights risks in their global value chains (GVCs). It offers a reiterative step-by-step procedure through which companies should take appropriate action in relation to actual or potential human rights impacts related to their business activities. The primary sources for HRDD are the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), often seen in conjunction with complementary guidance in the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).Footnote 1 HRDD requirements can also be found in various other (soft-law) instruments and documents. Fundamental labour standards (FLSs) are an essential part of those human rights and are incorporated in the UNGPs, OECD Guidelines, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and virtually all other public and private instruments dealing with international responsible business conduct.

The growing international consensus that other instruments with a more voluntary character are – by themselves – not sufficiently effective to promote responsible business conduct has led to the development of mandatory human rights due diligence (mHRDD) legislation in recent years.Footnote 2 It is important to mention that mHRDD is regarded as an important part of a necessary “smart mix” of – international, national, public, private, binding and voluntary – measures and instruments that together should be capable of effectively promoting respect for human rights by the private sector.Footnote 3 At the start of this legislative wave, mandatory rules focusing on disclosure were introduced, such as the California Transparency in Supply Chain Act of 2010, the UK Modern Slavery Act of 2015 and, at the European level, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive of 2014 (NFRD).Footnote 4 The French Loi au devoir de Vigilance of 2017, however, brought about a real turning point by introducing legal consequences for companies not meeting their HRDD obligations and has been widely regarded as an important model.Footnote 5 In particular, whereas most initiatives have so far relied on disclosure-based strategies that do not influence corporate behaviour directly,Footnote 6 by contrast, the French vigilance law takes a direct approach by requiring companies to change the ways in which they operate. The further introduction of legally binding corporate due diligence requirements is currently taking place on the domestic and regional level, with noteworthy developments in a number of European Member States and at the European Union (EU) level.Footnote 7

In this paper, we assess whether mHRDD can positively impact workers’ rights in GVCs. To this end, we next evaluate the current (international) legal framework of FLSs in GVCs in Section II and the legal impacts of the (proposed) mHRDD initiatives in Section III. With this normative background in place, we use the introduction of the French vigilance law to assess the effects of such a mandatory due diligence duty on human rights in GVCs (Section IV). The findings suggest that the direct approach of the French vigilance law can positively impact corporate human rights practices. This particularly holds for the practices of companies that can be considered as “laggards” (ie those that do not voluntarily comply with HRDD requirements).Footnote 8 Section V offers concluding remarks.

II. Fundamental labour standards and human rights due diligence

In order to understand the impact of mHRDD legislation on workers’ rights, it is necessary to address the basic features of HRDD and the scope and content of the FLSs. The FLSs are explicitly mentioned in the UNGPs as part of the minimum of human rights norms that need to be respected by companies.Footnote 9 They have been developed in the framework of the International Labour Organization (ILO), a specialised agency of the UN mandated to create and supervise international binding treaties (Conventions) and non-binding guidelines (Recommendations) on global work-related norms.

1. Scope and content of the fundamental labour standards

While the ILO has created many “international labour standards” in its century-long existence, a number of these standards are regarded as “fundamental”: in 1998, the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work was adopted, which identified four areas of special importance in protecting human rights at work worldwide.Footnote 10 These four areas are linked to eight specific Conventions of the ILO and deal with: (a) the effective abolition of child labour; (b) the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour; (c) freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; and (d) the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. Footnote 11

a. The prohibition of child labour

Child labour generally refers to work that jeopardises children’s education opportunities and is “mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children”.Footnote 12 It is furthermore defined by the ILO as “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development”.Footnote 13 While the number of child labourers worldwide had been in steady decline since 2000, the most recent estimates paint a bleaker picture. The 2021 joint report by the ILO and UNICEF on global estimates and trends related to child labour indicates that, for the first time in two decades, child labour is increasing, with about 160 million children trapped in child labour in 2020.Footnote 14 About 79 million of these children are performing hazardous work and slightly more boys than girls are engaged in child labour.Footnote 15 The two Fundamental Conventions containing the international norms on the prohibition of child labour are the Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138) and the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182).Footnote 16

Convention 138 of 1973 created a general convention, replacing a number of other, more specific conventions on the minimum age for admission to employment, with the purpose of effectively abolishing child labour and of progressively raising the minimum age for admission to work.Footnote 17 The Convention proposes a flexible framework with different categories: (a) a basic minimum age, (b) hazardous work and (c) light work.Footnote 18

Convention 182 of 1999, the first ILO Convention that has been ratified by all members of the ILO, has a different purpose and system than Convention 138.Footnote 19 Under the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, everyone below the age of eighteen is considered a child and no exceptions are provided for.Footnote 20 This is understandable considering the fact that Convention 182 covers the most harmful types of child labour. Article 1 emphasises that the prohibition and elimination of these types of child labour are the goals of the Convention as matters of urgency.Footnote 21 In Article 3, the different types of “worst forms of child labour” are specified. They comprise: (a) all forms of slavery, trafficking, debt bondage, serfdom and forced labour, including child soldiers; (b) the use of children in prostitution or pornography; (c) the use of children in illicit activities, particularly in drug trafficking; and (d) work that is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.Footnote 22 The final paragraph of Article 3 refers to hazardous work, a concept also covered by Convention 138.

b. The prohibition of forced and compulsory labour

According to research by the ILO, over 40 million people worldwide are victims of modern slavery.Footnote 23 About 15 million of those are trapped in forced marriages, while 25 million are engaged in forced labour.Footnote 24 Of the approximately 16 million people in forced labour in the private sector, about 50% were in debt bondage. Forced labour is closely related to the prohibition of slavery, which is a ius cogens norm under public international law. Two ILO Conventions have been earmarked as fundamental conventions in relation to forced labour: Convention No. 29 of 1930 and Convention No. 105 of 1957.Footnote 25

Convention 29 is one of the oldest Conventions of the ILO and has been widely ratified by its members.Footnote 26 Its purpose is to “suppress the use of forced or compulsory labour in all its forms within the shortest possible period”.Footnote 27 Article 2 of the Convention contains the definition of forced labour: “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”.Footnote 28 The second fundamental convention dealing with forced labour is Convention 105, which highlights a number of specific situations in which forced labour should be suppressed and calls for the complete and immediate abolition of these specific forms of forced labour.Footnote 29

In 2014, a new Protocol and Recommendation to the 1930 Forced Labour Convention were adopted that aim to bring ILO legislation more in line with present-day forms of forced and compulsory labour (modern slavery).Footnote 30 The Protocol and Recommendation provide guidance on important, victim-orientated aspects of forced labour, such as prevention, protection and compensation, and they offer tools to address forced labour, such as due diligence, inspection, international cooperation and complaint mechanisms.Footnote 31

c. Freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining

Freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining are at the heart of labour rights protection and are enabling rights that promote “industrial democracy” and provide workers with a fair voice in the establishment of fair and decent working conditions. A well-developed system of social dialogue is often a precondition for sound labour market governance on different levels.Footnote 32 Two ILO Conventions deal with these rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining.Footnote 33

While Convention 87 is ratified by 155 of the ILO’s Member States, large players on the world stage, such as China and the USA, have not ratified this fundamental convention. The core principle of Convention 87 is included in Article 2, which states: “Workers and employers, without distinction whatsoever, shall have the right to establish and, subject only to the rules of the organisation concerned, to join organisations of their own choosing without previous authorisation.”Footnote 34 This principle of non-interference by public authorities is reflected in Article 3, which stipulates that workers’ and employers’ organisations have the right to draw up their own rules and organise their own administration and activities, and Article 4, which states: “Workers’ and employers’ organisations shall not be liable to be dissolved or suspended by administrative authority.”Footnote 35 These guarantees apply to all workers, as well as those in the informal sector, self-employed and (undocumented) migrant workers, for example.

While Convention 87 is mostly focused on the relationship between public authorities and workers’ and employers’ organisations, the provisions in Convention 98 are more relevant to the relationship between workers’ organisations and corporate management. The goal of Convention 98 is to protect trade union members against unfair treatment and to support a fair and effective collective bargaining process.Footnote 36 Article 1 of the Convention prohibits acts of anti-union discrimination, in particular those that prohibit workers from joining trade unions or those that lead to dismissals, demotions or transfers of workers related to their membership of workers’ organisations.Footnote 37 The principle of non-interference is laid down in Article 2, which stipulates: “Workers’ and employers’ organisations shall enjoy adequate protection against any acts of interference by each other or each other’s agents or members in their establishment, functioning or administration.”Footnote 38

d. Non-discrimination and equal treatment in employment and occupation

A final centrepiece of ILO standard setting is the promotion of equal treatment in relation to occupation and employment. While numerous ILO instruments include equal treatment provisions, sometimes tailored to specific vulnerable groups,Footnote 39 two instruments are designated as fundamental conventions: Convention 111, the Discrimination Convention, and Convention 100, the Equal Remuneration Convention.Footnote 40 Problems in relation to discrimination and unequal treatment at work are pervasive and persistent in all jurisdictions and represent an important theme in EU social legislation.

Convention 111 is a general instrument that requires ratifying Member States to “declare and pursue a national policy designed to promote, by methods appropriate to national conditions and practice, equality of opportunity and treatment in respect of employment and occupation, with a view to eliminating any discrimination in respect thereof”.Footnote 41

Article 1 includes the definition of discrimination and mentions seven specific grounds: “any distinction, exclusion or preference made on the basis of race, colour, sex, religion, political opinion, national extraction or social origin, which has the effect of nullifying or impairing equality of opportunity or treatment in employment or occupation”.Footnote 42 The list of grounds is not exhaustive and may be (and often is) supplemented at the national level.Footnote 43

While Convention 111 offers a general prohibition of discrimination in relation to work, Convention 100 deals with a very specific issue: equal pay for men and women workers for work of equal value. The Convention addresses the gender wage/pay gap, which is a very present phenomenon in all jurisdictions.Footnote 44 According to Article 2(1), Member States are to “promote and, in so far as is consistent with such methods, ensure the application to all workers of the principle of equal remuneration for men and women workers for work of equal value”.Footnote 45 Gender gaps in relation to remuneration remain one of the “greatest sources of inequality” today.Footnote 46

These FLSs are often under pressure near the bottom of global supply chains; think, for instance, about agriculture, extractive industries or low-skilled work such as in the garment industry. FLSs therefore represent important part of the norms that are to be protected and respected under the voluntary initiatives that generate HRDD requirements, to which we will turn in the next subsection.

2. Key features of HRDD

The UNGPs are considered to represent a ground-breaking instrument in the field of ascribing responsibilities for human rights violations to companies. They include the “protect, respect, remedy” framework developed by John Ruggie.Footnote 47 Under this system, companies have a duty to respect human rights and make sure that they address violations in which they are involved. Furthermore, victims of human rights violations need to have access to fair remedies. The normative foundations for the UNGPs are the International Bill of Human Rights and the ILO’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.Footnote 48 Companies need to commit publicly to the UNGPs and implement procedures and policies to “enable the remediation of any adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which they contribute”.Footnote 49

An essential feature of the UNGPs is that companies are to conduct a HRDD process to “identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their impacts on human rights”.Footnote 50 This process, which is meant to help companies to anticipate and mitigate any adverse human rights impacts associated with their business activities,Footnote 51 has been integrated into the 2011 revised version of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. The OECD guidelines offer a six-step framework for HRDD and also refer to the content of the (Fundamental) Conventions of the ILO and many other work-related norms.Footnote 52

Step 1 of this framework concerns embedding responsible business conduct in corporate policies and management systems, including corporate oversight bodies.Footnote 53 Then, in Step 2, companies identify and assess any (potential) adverse impacts, including a broad scoping exercise across their entire GVCs to identify areas in which risks are most likely to be present and most severe.Footnote 54 Subsequently, an in-depth assessment of the prioritised areas needs to be conducted in order to reveal specific potential and actual human rights impacts.Footnote 55

In Step 3, companies cease, prevent and mitigate any adverse impacts, which include stopping activities that are causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts and implementing plans that mitigate actual or potential adverse impacts directly linked to the company’s operations.Footnote 56 This process may include responses such as a (temporary) suspension of a relationship.Footnote 57

Step 4 requires that businesses track the implementation and effectiveness of the company’s HRDD activities. The lessons learned from its measures to identify, prevent, mitigate and potentially remediate impacts should be taken into account for future HRDD improvements.Footnote 58

In turn, Step 5 concerns the need to communicate and publish relevant information on how the impacts are addressed, including the findings and outcomes of the activities that were undertaken in this respect.Footnote 59

Finally, Step 6 requires that companies provide for or cooperate in the remediation of adverse impacts in cases where it has caused or contributed to such impacts. Where appropriate, this may include cooperation with legitimate remediation mechanisms by which stakeholders can raise complaints. These may include judicial or non-judicial mechanisms.Footnote 60

From these six steps, it follows that HRDD is a preventative and dynamic learning process that is risk-based, which means that companies need to take into account the severity and likelihood of the adverse impacts in their risk assessments, which could include a prioritisation of risks.Footnote 61 Companies need to be able to adapt to changing circumstances and adequately respond to changes in risk profiles.Footnote 62 Meaningful, good-faith engagement with and consultation of various stakeholders as well as ongoing communication are key throughout the HRDD process.Footnote 63 With these basic features of HRDD in place, we can now explore the development towards mandatory legislation.

III. Recent mandatory human rights due diligence initiatives

Several authors have considered the comparative advantages of soft- and hard-law regulatory strategies related to human rights.Footnote 64 Whereas soft law has clear advantages, including allowing companies time to experiment with best practices and guidanceFootnote 65 and recognising and stimulating the dynamic learning process,Footnote 66 hard law can create binding obligations that have a direct impact on corporate decision-making and create a level playing field for companies. Whereas the advantages of soft law should not be neglected,Footnote 67 mHRDD legislative initiatives are introduced to answer the ever-growing call for mandatory rules to establish improvements in GVCs.Footnote 68 The first general mandatory initiative is the French Loi au devoir de Vigilance from 2017.Footnote 69 Under this law, companies need to prepare and implement a vigilance plan that allows for risk identification and prevents severe human rights violations resulting directly or indirectly from the operations of the company and its supply chain.Footnote 70 Companies that are non-compliant can face an injunction,Footnote 71 and the law also enables civil action for victims to require compensation for damages resulting from non-compliance with this vigilance duty.Footnote 72 However, in contrast to the UNGPs, which take into account the entire GVC, the legally binding obligation to identify and prevent adverse human rights and environmental impacts that follows from this French law is limited to a company’s own activities, its subsidiaries and its subcontractors and suppliers with whom it has an “established commercial relationship”.Footnote 73 In addition, while the UNGPs do not limit the scope of companies, the French law only applies to large companies.Footnote 74 It also does not address the existing legal hurdles in civil enforcement for tort victims, including the burden of proof.Footnote 75 The 2020 monitoring report by the French High Council for Economy proposes the instalment of a supervisory authority to overcome some of these existing flaws.Footnote 76

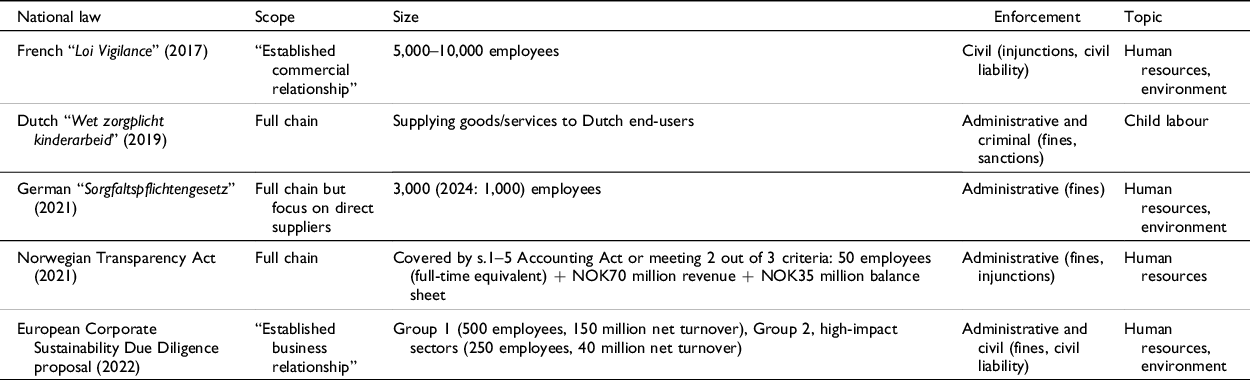

While recognising the deviations from the established HRDD framework, authors are generally positive about the possible effects of the French vigilance law and claim that it provides important lessons for further mHRDD initiatives.Footnote 77 In particular, before the introduction of the French law, many other regulatory initiatives typically entailed disclosure-based strategies, such as the NFRD and the UK Modern Slavery Act of 2015. Bruner notes that these regulatory initiatives are unlikely to substantially improve matters on their own. He argues, inter alia, that these disclosure initiatives do not directly require corporate actors to change anything about their current operations or offer incentives, so that they are unlikely to change corporate decision-making. By contrast, he notes that the French vigilance law does have the potential to affect the incentives of corporate decision-makers by imposing liability and affecting risk incentives, although legal actions remain pending.Footnote 78 Other national mHRDD initiatives introduced after the French law that may have a similar potential include, for instance, the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Act of 2019,Footnote 79 the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act of 2021 (Sorgfaltspflichtengesetz)Footnote 80 and the Norwegian Transparency Act of 2021.Footnote 81 As Table 1 displays, these regulatory initiatives differ widely on various aspects, resulting in fragmentation and legal uncertainty for global enterprises.Footnote 82

Table 1. Mandatory human rights due diligence legislation and initiatives.

The European Commission’s proposal of 23 February 2022 for a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) offers harmonised corporate sustainability due diligence duties for companies with extraterritorial effects and to a large extent incorporates the six HRDD steps in Articles 5–11. However, there also seem to be some (unnecessary) deviations in this proposal from the international soft-law framework that we discussed in Section II.2. For instance, similarly to the French law, the scope of responsibility is limited to “established business relationships”Footnote 83 and does not cover the entire GVC. In addition, there is a significant emphasis on contractual assurances, including independent third-party verification and model contractual clauses,Footnote 84 whereas it seems that the importance of sectoral initiatives and other multi-stakeholder instruments that are central to the (voluntary) dynamic HRDD process is not fully recognised in the proposal.Footnote 85 As there is currently significant discussion among legislators, scholars and other stakeholders on these and other aspects of the proposed CSDDD, we probably can expect several amendments to this in the further legislative procedure.

To conclude, although it should be designed carefully, leveraging the years of experience resulting from voluntary requirements, there is a growing consensus that mandatory legislation is indispensable to impacting corporate decision-making in order to address and prevent human rights infringements in GVCs. In the next section, we take the French vigilance law as an example to empirically evaluate whether mHRDD indeed can have these desirable effects.

IV. Empirical analysis

This section includes a simple empirical analysis of the French Loi au devoir de Vigilance that was introduced in 2017. Some studies show evidence of an impact of this law on corporate HRDD practices,Footnote 86 but to our knowledge there is no empirical analysis that compares companies that are required to comply with mHRDD and those that are not. In this research, we offer the first insights into the possible effects of the French vigilance law in an empirical setting.Footnote 87 In the following subsections, we first introduce the data and research sample (Section IV.1) and then we show our findings (Section IV.2).

1. Data and sample selection

We use the human rights scores provided in the Refinitiv Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) database to measure the effect of the French law on corporate human rights practices. The Refinitiv human rights score is one of the ten components that together form the Refinitiv ESG score, and it is based on a numerical scale ranging from 100 (good performance) to 0 (poor performance). The score is based on collected information from publicly available information sources, including information provided by companies, but also from media and news, stock exchange filings and non-governmental organisation (NGO) websites.Footnote 88 It consists of fourteen components (see Table A1 in the Appendix) that are closely aligned with human rights and FLSs as part of HRDD.Footnote 89

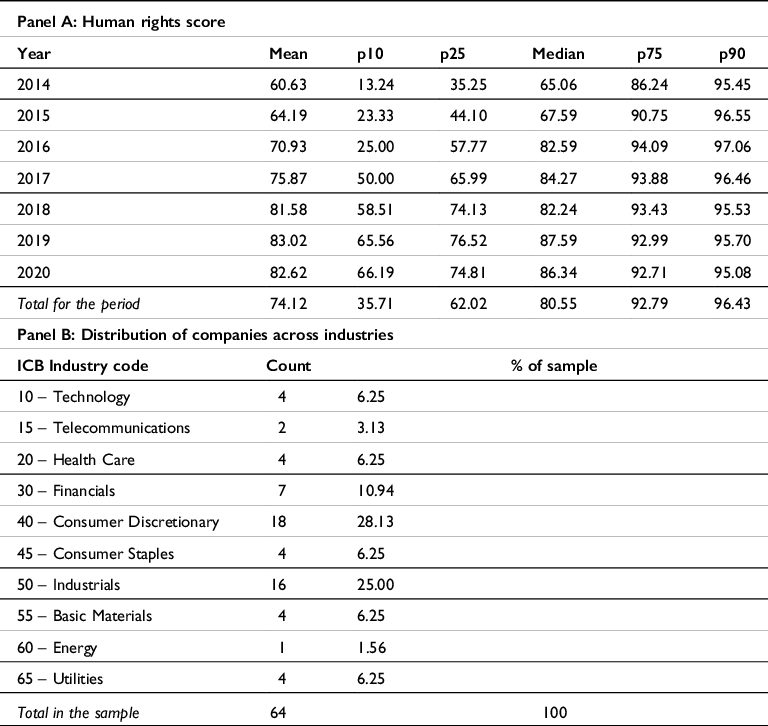

We received a non-exhaustive list of 265 French companies subject to the French vigilance law including their compliance with the law from the French NGO CCFD-Terre Solidaire (working together with the NGO Sherpa). From 2018 onwards, they annually identified those companies that needed to comply with the French vigilance rules and monitored them.Footnote 90 For sixty-four of these large (listed) French companies subject to law, we were able to obtain the Refinitiv human rights scores for the entire 2014–2020 sample period. Table 2 provides descriptive sample information.

Table 2. Descriptive information for the treatment group.

Note: The table shows the descriptive information for our sample companies that need to comply with the French vigilance law. The table shows the mean human rights score per year and sample average and also the 10th (p10), 25th (p25), 50th (median), 75th (p75) and 90th (p90) percentiles (Panel A). For many companies, the Refinitiv human rights score is usually updated once per year based on the corporate disclosures. The vast majority of those disclosures take place during the fourth quartile. To align with corporate disclosure practices, updates based on disclosures in the first quartile of the next year (until 31 March) were taken into account for the year before. For instance, the fiscal year of Alstom SA takes place from 1 April to 31 March. The table also shows the Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) Industry code information of the companies in the sample (Panel B).

Could the mandatory French law have a positive impact on the human rights scores of the companies in our sample? The information in Table 2 signals that the French law may have had an impact on the laggards in our sample: for the 10th percentile, the human rights scores increase from an average of 25.00 in 2016 to 58.51 in 2018, which implies that the average score for these companies more than doubled since 2016 (including a possible anticipation effect). In addition, for the 25th percentile we see an average increase of the human rights score of about 16 in the 2016–2018 period. By contrast, for the companies with higher human rights scores before the implementation of the French law, the effect seems to be smaller or even to be lacking entirely.

To determine whether the increased human rights scores may be related to the implementation of the French vigilance law, we compare the characteristics of our treatment group (ie the sixty-four companies that need to comply with the French vigilance law) with similar companies that do not need to comply with this law. These control companies were taken from the entire universe of companies in the Refinitiv database for which human rights scores were available in the 2014–2020 sample period.Footnote 91 From the 3,424 companies for which all variables were available for the full sample period, we obtained pairs with close covariate values using Mahalanobis distance matching with replacement.Footnote 92 For each treated observation, we found the most similar untreated observation in 2016, which is the year before the French law was introduced. To ensure parallel trends occurred before the treatment took place, the human rights scores of 2014 and 2015 were included as matching covariates. To be able to capture the effects on the laggards in particular, we calculated difference-in-differences estimators for two matched treatment groups: the full sample of treatment companies and their matches; and a reduced sample that includes those treated companies that have a lower human rights score than the average of the treated companies in 2016 and their matches (called “the laggards”). We also used both the full Refinitiv control sample for matching and a reduced sample of only EuropeanFootnote 93 control companies. Table A2 in the Appendix shows the descriptive information for several of these matched pairs.

2. Results

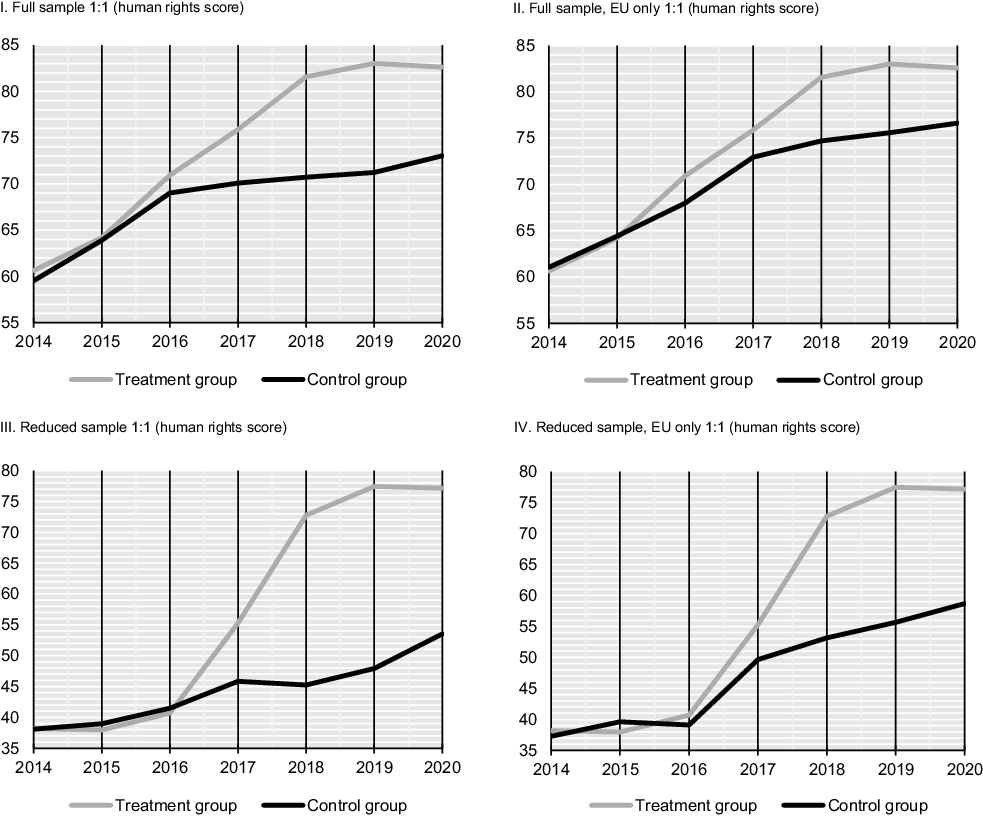

In this section, we estimate the effect of the French vigilance law on the human rights scores of our treated companies using the full and reduced matched samples. Figure 1 shows the trend of the human rights scores for the matched samples, demonstrating that there may be a significant treatment effect resulting from the French vigilance law, particularly for the laggards in the reduced sample. From 2016 to 2017, we can see already an (anticipation) effect of the introduction of the vigilance law, and from 2017 to 2018, we see the largest increase in human rights scores for the treated companies in the laggards group. This finding is in line with Bruner, who states that the French vigilance law directly impacts corporate decision-making.Footnote 94 Figure 1 displays that the matched control sample of European companies that experienced a larger increase in their human rights scores than the control sample based on the full Refinitiv database, both for the full and the reduced sample of laggards. Although Bruner argues that it is unlikely for disclosure obligations to directly impact corporate decision-making,Footnote 95 the results perhaps signal that the NFRD that was implemented by many Member States around 2017 may have had a positive impact on the human rights practices of companies. However, it should be noted that the French companies subject to the vigilance law still outperform these other European companies.

Figure 1. Trend lines (mean human rights scores, matched sample).

Note: Graphs I and II include the full sample of sixty-four treatment companies and their 1:1 matched control companies, and Graphs III and IV show the reduced sample of twenty-four treatment companies (the “laggards”) and their 1:1 matched control companies. Graphs II and IV only include European control companies (including Swiss companies). Groups of control companies following a 3:1 matching strategy and European control companies excluding Swiss companies provide similar trends.

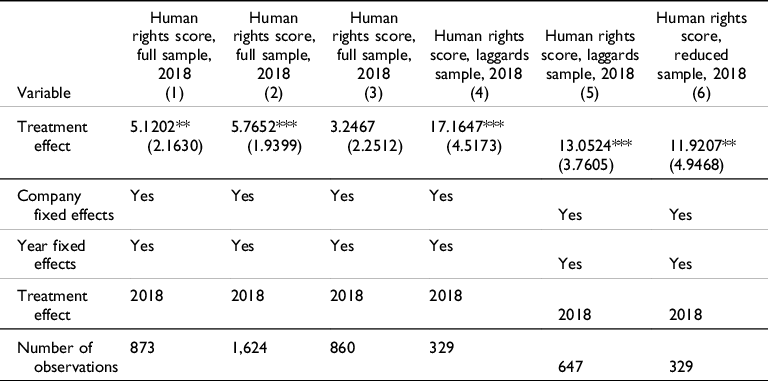

We conduct difference-in-differences panel regression analyses with fixed effects to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated companies in order to see whether the diverging trends in Figure 1 are also statistically significant. Although further research is needed to determine any causal relationships, the results in Table 3 show that for both the full and the laggard samples the treatment effect is statistically significant and positive in most models. Particularly for the reduced sample with laggards, the identified treatment effect is large: Models 4–6 show that, on average, the French vigilance law caused companies to increase their human rights score by more than 12 in 2018.Footnote 96

Table 3. Difference-in-differences estimator.

Note: The table displays the panel data difference-in-differences estimator using company and year fixed effects. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Models 1–3 display the full matched sample and Models 4–6 display the reduced matched sample of laggards. Models 2 and 5 contain 3:1 matching, all other models contain 1:1 matching. Models 3 and 6 include the sample of European control companies (including Swiss companies, but models estimated excluding Swiss control companies show similar results). Control variables for company size (in market capitalisation) and return on assets are included in all models. The parallel trend assumption holds for all models. The treatment effect is estimated for the year 2018. The treatment effects for 2019 are also statistically significant for all samples (not reported), but the treatment effects estimated for 2017 are not statistically significant (not reported). Several estimated models with different matching estimators show statistically significant treatment effects as well (not reported).*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Figure 1 and Table 3 show that the possible significant impact of the vigilance law is mainly driven by the improvements among the laggards. This could suggest that the other companies already (to a large extent) comply with these obligations that previously only resulted from the soft HRDD framework. Although this certainly could be the case for (some of) the leaders,Footnote 97 it should also be noted that the French vigilance law has some important shortcomings, such as limiting the obligations to established commercial business relationships and preserving the existing legal hurdles for tort victims as discussed in Section III. As a result, the French vigilance law may only be capable of improving the scores of the laggards. The stagnant scores of both treatment groups in 2020 seem to support this conclusion. The large variety in the different national mHRDD initiatives and the heated discussions regarding the design of the CSDDD at the European level show that there are various ways for national and European legislators to increase the mHRDD requirements in order to improve corporate performance. In this respect, it is also recommended that legislators carefully reflect on the possible side effects of mHRDD requirements. Most initiatives focus on large companies only (see Section III for the different requirements): this may signal to companies that fall outside the scope of these initiatives that there is no need for them to comply with any of the (voluntary) due diligence requirements. For this reason, we would recommend legislators to consider the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Act that introduces a general duty of care for all companies that sell or supply goods or services to Dutch end-users (see Section III). In addition, due to the particular advantages of the nature of soft law, other elements such as sectoral initiatives and other multi-stakeholder instruments remain important for a comprehensive approach to sustainable GVCs.Footnote 98

Furthermore, Table 2 shows that components 10–14 of the Refinitiv human rights score deal with controversies. Although speculative, one could argue that after the introduction of the French vigilance law there probably was more coverage of human rights controversies in the media. In this case (the vigilance law leading to more media coverage and to the identification of more human rights controversies), the improvements in the other components of the human rights scores might be even bigger than our analyses show. Yet a further consideration of components 10–14 shows that there is little variation and thus does not provide any evidence for this line of reasoning.

Finally, the question can be raised as to whether the results for the treatment companies could (also) be driven by the implementation of the NFRD in 2017. Although more research is recommended here as well, it should be noted that French listed companies were already required to publish non-financial information before the implementation of the NFRD, and this legislation was expanded to unlisted companies that meet certain thresholds within the Grenelle II legislation in 2010.Footnote 99 Particularly, Grenelle II includes forty-two indicators on which listed companies need to report, including, for instance, actions taken to promote human rights, working hours, health and safety conditions and collective bargaining agreements. The indicators also include the promotion and enforcement of the FLSs, explicitly referring to the basic ILO conventions. The legislation to implement the NFRD under French law was based Grenelle II, including these indicators, going beyond European requirements.Footnote 100 Therefore, it seems unlikely that our research results are (mainly) driven by the implementation of the NFRD and not the French vigilance law, although we cannot exclude any positive impacts resulting from the NFRD. In any case, the French vigilance law clearly goes beyond Grenelle II’s and the NFRD’s “comply or explain” obligation by establishing a duty of care for companies related to adverse impacts in their GVCs.Footnote 101

To conclude, although we admit that the presented empirical analysis is limited due to small sample sizes and flawed human rights data, the French vigilance law receiving substantial criticism and the advantages of soft law potentially being underemphasised, our findings signal that a mandatory duty of care can incentivise corporate decision-makers to internalise the social costs of their business operations.

V. Concluding remarks

mHRDD requirements are increasingly seen as the most effective way to compel (more) companies to (better) address human rights risks in their GVCs, including the FLSs, which are most often under pressure. While mandatory legislation seems to be an important tool for closing the gap between the corporate leaders and laggards when it comes to the protection of FLSs, it needs to be designed carefully with due consideration of possible adverse effects. Our empirical analysis signals that the French vigilance law seems to have had a significant positive effect in compelling laggards to increase their efforts towards more sustainable business models in which workers’ rights and other human rights are more effectively protected. Yet we recommend that European legislators increase the mHRDD requirements in the CSDDD to further improve the human rights conduct of companies.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2022.23.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.