Introduction

To starve to death is a small thing, but to lose one's integrity is a great one. (Chinese proverb)

Population ageing is a global issue (Chan, Reference Chan2014), and keeping a positive self-concept and high levels of subjective wellbeing have been considered aspects of successful ageing (Baltes and Baltes, Reference Baltes, Baltes, Baltes and Baltes1990). Self-integrity, as a core component of the self-system (Cohen and Sherman, Reference Cohen and Sherman2014), is closely related to the concept of self in successful ageing and plays an important role in self-affirmation to achieve socially acceptable behaviour. To explain briefly the core concept of self-integrity by self-affirmation theory, people are motivated to maintain a global image of self-integrity (Sherman and Hartson, Reference Sherman, Hartson, Alicke and Sedikides2011), which plays a vital role in social interaction. Crocker et al. (Reference Crocker, Niiya and Mischkowski2008) found that self-integrity induces positive and other-directed emotional states, such as love and connectedness. Additionally, self-integrity could make people more open and less stubborn to opponents' opinions in negotiations (Falk et al., Reference Falk, O'Donnell, Cascio, Tinney, Kang, Lieberman and Strecher2015). The probable benefits of self-integrity are supported by a meta-analysis, which demonstrated that self-integrity can promote acceptance of health maintenance, facilitate intents to change health behaviours and inspire behavioural changes (Epton et al., Reference Epton, Harris, Kane, van Koningsbruggen and Sheeran2015). Self-integrity plays a crucial role in eliminating self-threats and enhancing the ability to ameliorate physiological responses to stress (Harris and Epton, Reference Harris and Epton2009).

Several studies have suggested that self-integrity is an important tool for older adults to overcome emotional and behavioural problems (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Munford, Thimasarn-Anwar, Liebenberg and Ungar2015; Ai et al., Reference Ai, Morris, Ordway, Quinoñez, D'Agostino, Whitfield-Gabrieli, Hillman, Pindus, McAuley, Mayo, de la Colina, Phillips, Kramer and Geddes2021; Dang et al., Reference Dang, Bai, Zhang and Lin2021a, Reference Dang, Wu, Bai and Zhang2021b). Older adults with a greater integrated self are expected to be more inclined to recognise personal needs and desires and to take an active stance against self-stereotypes. Previous studies have shown that self-system is established by individuals through the process of external (culture) and internal comparison (personality variables) (Sherman and Cohen, Reference Sherman and Cohen2006). Individuals gradually form their own self-system through internalising external perspectives (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Winer, Goodvin, Bornstein and Lamb2011). Different cultural backgrounds have many stereotypes of older adults, such as amnesia, intellectual incompetence, and slow or disorientated thinking style (Hummert et al., Reference Hummert, Garstka, Shaner and Strahm1994). When people reach old age, ageing stereotypes that begin to be incorporated in childhood, and strengthened for decades thereafter, become self-stereotypes (Snyder and Miene, Reference Snyder, Miene, Zanna and Olson1994). If these stereotypes persist for a long time, then they will convert into self-concepts of ageing. Therefore, the more people are exposed to negative stereotypes, the more they would endorse negative views of their own ageing when they enter old age (Sargent-Cox et al., Reference Sargent-Cox, Anstey and Luszcz2012). Stereotypes of older adults are often internalised into the self-system, forming self-stereotyped images that lead to a certain impact on the self-system (Levy and Banaji, Reference Levy, Banaji and Nelson2002); these self-stereotypes may cause low self-integrity (Livingston and Boyd, Reference Livingston and Boyd2010).

Self-integrity is threatened when people's sense of self-worth is affected by stereotyped domains (Steele et al., Reference Steele, Spencer, Aronson and Zanna2002). If older adults internalise many negative ageing stereotypes in childhood, then it would affect the formation of their self-integrity and lead them to internalise self-stereotypes in their later years of life. Age-based self-stereotype threat and self-integrity have a close relationship (Sherman and Cohen, Reference Sherman and Cohen2006). Hence, self-integrity, as a core concept of self-system, should also be closely related to the self-stereotype of older adults. Older adults experience different threats to self-integrity (Sherman and Cohen, Reference Sherman and Cohen2006). Self-stereotype affects stigmatised persons' local world as reputation, health and life chances, and devastates self-integrity thereafter (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Gibson, Lueke, Huesmann and Bushman2014). Accordingly, self-stereotypes should be closely related to the self-integrity of older adults.

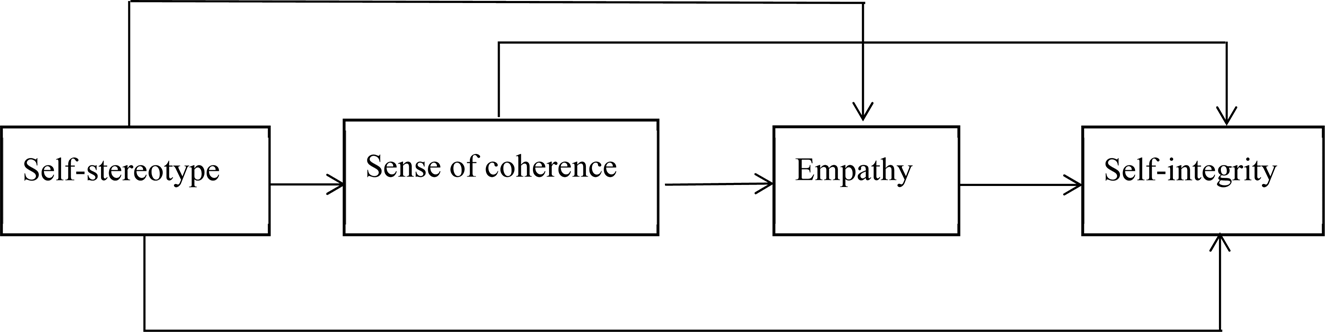

Another concern in the field is the mechanisms involved in the effects of self-stereotypes on integrity in older adults. That is, there may be some variables acting as intermediaries in the relationship between self-stereotypes and self-integrity. This study proposes a multi-mediational model of self-integrity, in which self-stereotype may have effects on sense of coherence and empathy, thereby affecting self-integrity amongst older adults.

We used previous findings as bases in proposing a model of internalised stigma effects on self-integrity, including sense of coherence as a potential mediating factor. Sense of coherence is an important notion in salutogenesis theory and is defined as ‘a global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence’ that the world is meaningful, understandable and manageable (Antonovsky, Reference Antonovsky1979: 123). In previous literature, sense of coherence has been shown to have mediating effects on the impact of stressors, including stereotype threats on health (Eriksson and Lindström, Reference Eriksson and Lindström2006). Accordingly, sense of coherence may be reasonably expected to play a mediating role in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity. Sense of coherence would increase over the years owing to life event experiences and play a vital role to attain self-integrity. The literature has shown that sense of coherence benefits health outcomes, enhances self-integrity, and mediates the relationship between stressful circumstances and wellbeing outcomes (Feldt et al., Reference Feldt, Kinnunen and Mauno2000). Research amongst older adults has shown that a strong sense of coherence is related to quality of life, which includes high self-integrity and fewer disturbing behaviours (e.g. self-stereotypes) (Eriksson and Lindström, Reference Eriksson and Lindström2006). This result may indicate that sense of coherence should be closely related to the self-integrity of older adults. Moreover, self-stereotype may affect sense of coherence in older adults. A substantial body of research has shown that stigmatisation may have several detrimental effects on the older population by reducing sense of coherence (Corrigan and Kleinlein, Reference Corrigan, Kleinlein and Corrigan2005). Evidently, identifying the mediating effects of sense of coherence is an important indicator that highlights the mechanism through which self-stereotype affects the subjective wellbeing of people; accumulated evidence has demonstrated that a stronger sense of coherence is associated with better health, particularly under stigmatised behaviour (Eriksson and Lindström, Reference Eriksson and Lindström2006). Langeland et al. (Reference Langeland, Riise and Hanestad2006) developed a talk-therapy group programme to enhance awareness of sense of coherence. The results showed that the programme successfully raised participants' awareness of potential internal resistance resources and external resistance resources, thereby improving the participants' sense of coherence, coping with stereotypes and mental health level. The preceding findings indicate that an increase in sense of coherence may have the potential to break the chain of negative effects triggered by self-stereotype (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Byrne, Varese and Morrison2016). Briefly, self-stereotype may have some negative effects on sense of coherence, which is closely related to self-integrity. That is, sense of coherence may play a mediating role in the effects of self-stereotype on self-integrity.

Apart from sense of coherence, empathy may be another mediator for the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity. Empathy is defined as the ability to understand others' emotions, perspectives and, often, to resonate with others' emotional states (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Eggum and Giunta2010). Additionally, empathy is a multi-dimensional construct and its affective and cognitive processes help to form an empathic response (Decety, Reference Decety2015). In previous literature, empathy and self-integrity have long been conceptually linked (Blair, Reference Blair, Arsenio and Lemerise2010). Self-integrity regulates the behaviour of others in society, and one can attain a concern for people by empathising with them. With the absence of empathy, self-system would never attain emotional grounding. Thus, Blair (Reference Blair1995) concluded that empathy is necessary for self-integrity. With further cognitive processing, empathic response may develop into empathic concern, guilt or a combination of the two (Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Mashek2007). Such typical moral emotions are thought to provide the motivational force to ‘do good’ and avoid ‘doing bad’ (Moll and de Oliveira-Souza, Reference Moll and de Oliveira-Souza2007), providing immediate and salient feedback on self-integrity (Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Mashek2007). By contrast, impairments in empathy (Adolphs, Reference Adolphs2001) have been associated with antisocial or immoral behaviour (Winter et al., Reference Winter, Spengler, Bermpohl, Singer and Kanske2017). A previous study has shown a relationship amongst self-integrity, empathy, and prosocial or helping behaviour. Eisenberg and Miller (Reference Eisenberg and Miller1987) conducted a meta-analysis of 41 samples and found that empathy is positively related to helping behaviour, which develops self-integrity in people. Batson et al. (Reference Batson, Chang, Orr and Rowland2002) indicated that empathic processes are important for stereotypical attitudes in judgements, which is consistent with the results of previous findings. Although there is evidence of the negative association between empathy induction and use of stereotypes, minimal attention has been given to whether or not priming stereotypes may minimise empathic processes. For example, Batson et al. (Reference Batson, Chang, Orr and Rowland2002) conducted a more direct test of the link between empathy and intergroup attitudes and found that stereotype threats lead people to communicate less with others and reduce empathic opportunities. Empathic communication is particularly important in the context of stigma. In older adults, empathic communication may help to reduce stigma and promote engagement for better health outcomes (Michaels et al., Reference Michaels, Weiss, Guidry, Blakeney, Swords, Gibbs, Yeun, Rytkonen, Goodman, Jarama, Greene and Patel2012). Similarly, self-stereotypes mitigate empathic concern in older adults. Previous studies have focused on how empathic opportunities are missed because of psychosocial outcomes, such as stigma (e.g. Easter and Beach, Reference Easter and Beach2004). Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Bushman and Dovidio2008) found that priming the ‘promiscuous Black female’ stereotype reduces empathy for a Black pregnant woman-in-need. Previous research has revealed a close relationship between self-stereotype and empathy, as well as a significant relationship between empathy and self-integrity. On the bases of these findings, empathy is expected possibly to play a mediating role in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity in older adults.

Lastly, we also expect a mediating effect of the chain from sense of coherence to empathy in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity. From the global mental health perspective, we have to recognise that sense of coherence and empathy are fundamentally crucial elements for establishing and maintaining all of our most significant relationships based on self-integrity (Jakovljevic and Tomic, Reference Jakovljevic and Tomic2016). Empirical study has shown that a strong sense of coherence aids the development of positive empathy (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Zhang and Li2013). Particularly, past research has shown that the greater the sense of coherence, the higher the empathy (Pålsson et al., Reference Pålsson, Hallberg, Norberg and Björvell1996). The preceding evidence indicates the plausibility of believing that sense of coherence can help people feel considerably empathic. Thus, the chain from sense of coherence to empathy may play a serial mediating effect on the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity.

The current study drew on the preceding literature review in investigating the patterns of relationship amongst self-stereotype, sense of coherence, empathy and self-integrity. The hypothesised model of the current study is presented in Figure 1. The hypotheses of the current study are as follows:

• Hypothesis 1: Self-stereotype is a significant predictor of self-integrity.

• Hypothesis 2: Sense of coherence mediates the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity.

• Hypothesis 3: Empathy mediates the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity.

• Hypothesis 4: The chain from sense of coherence to empathy plays a serial mediating effect on the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Method

Participants

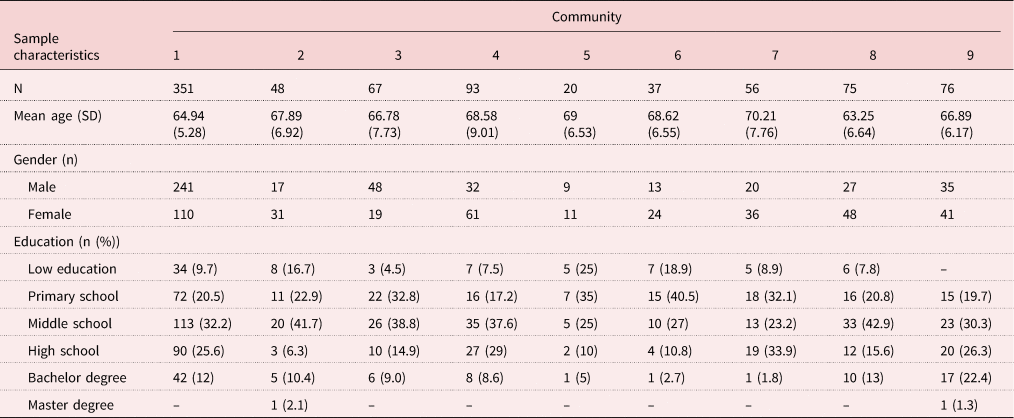

All participants in this study were community-dwelling older adults in Beijing and Xi'an. We selected representative communities in the two cities. We comprehensively considered two factors, considering the representativeness of our sample: (a) length of time that a community had been in existence and (b) its population size. In both cities, we selected communities with medium-sized populations (i.e. approximately 10,000 people) that had been established in less than 10 years, more than 20 years or more than 30 years to recruit participants for the investigation. Eventually, we selected nine communities with a total population of over 100,000, approximately one-third of whom were older adults. Average length of time that these communities had been in existence was approximately 15 years. These communities have a large population base, stable community environment and interpersonal relationships, thereby helping to guarantee the randomness and representativeness of the sample selection. We obtained verbal consent from the nine neighbourhood committees, which are self-governing administrative organisations responsible for the care and maintenance of specific communities and the residents within their jurisdiction. A total of 1,168 questionnaires were distributed. After introducing the survey, some older adults refused to participate because they needed to take care of their grandchildren, buy food or cook. The final sample consisted of 825 older adults aged 55 or above (mean age = 66.23, standard deviation = 6.83), for a response rate of 70.6 per cent. The number of participants and their characteristics in each community is shown in Table 1. The benefit of using large samples is that it allows the innovation of rare discoveries or rare instances that cannot be uncovered by using small samples, given that the latter is appropriate to discover only average behaviour. The purpose was to ‘reduce the chances of discovery failure’ because a large sample size widens the range of possible data and forms a better picture for analysis (DePaulo, Reference DePaulo2000). Additionally, using a sample size of over 300 is considered large and sufficient for a superior effect size to measure practical and statistical significance (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lucas and Shmueli2013).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Notes: N = 825. SD: standard deviation.

Measures

Self-stereotype

The scale is designed to measure one's subjective feelings of self-stereotype. A total of ten items measure self-stereotypes of the elderly: six items were from the stereotype subscale of the adapted version of the Faboni Scale of Ageism (Rupp et al., Reference Rupp, Vodanovich and Crede2006) and four items were from a questionnaire assessing domain-specific age stereotypes developed by Kornadt and Rothermund (Reference Kornadt and Rothermund2011). These ten items were all about negative stereotypes of older adults. We revised the subject of the ten items to the first person (e.g. ‘I am stingy and hoard money’). A previous study has tested the reliability and validity of the self-stereotype scale in Chinese older adults and has proven that the scale has good reliability and validity in the referred population group (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Bai, Zhang and Lin2021a; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhang and Lin2021). The participants rated each item using a four-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Items were averaged to create an index, with higher scores representing higher levels of negative self-stereotype. Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.70 in the present study.

Sense of coherence

Sense of coherence was measured using the Chinese version of the 13-item scale, which is a brief version of Antonovsky's (Reference Antonovsky1987) Orientation to Life questionnaire (revised by Bao and Liu, Reference Bao and Liu2005). This scale has relatively acceptable internal consistency coefficients (Bao and Liu, Reference Bao and Liu2005). Moreover, the Chinese version of the sense of coherence scale has been widely used in the study of the elderly population and has been shown to have good reliability and validity (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Du, Liu, Guo, Zhang, Qin and Liu2019; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Zhang and Xu2022). Participants were asked to complete the 13 items (e.g. ‘When you talk to people do you have the feeling that they don't understand you?’) by using a seven-point Likert scale. Higher average scores indicate a higher level of sense of coherence. Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.76 in the present study.

Empathy

Empathy was measured using the subscales of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, Reference Davis1980), which is a 28-item multi-dimensional self-report measure with four subscales. Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Dong and Wang2010) conducted reliability and validity tests for the Chinese version of the IRI and standardised the Chinese version (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Dong and Wang2010). Additionally, other studies using the Chinese version of the IRI showed that the scale has good reliability and validity in the Chinese population (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Li, Sun, Chen and Davis2012; Chiang et al., Reference Chiang, Hua, Tam, Chao and Shiah2014; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Bi and Yan2021). Although the IRI was developed as a four-dimension scale, researchers often use IRI scores flexibly in their studies based on the different definitions and constructs of empathy they advocate (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Xiao, Fu and Jie2020). Given that the current study focused on older adults' tendency to experience feelings of concern or compassion for others, only the empathic concern subscale was used. All items (e.g. ‘I often get concerned about what I see’) were scored using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate a higher level of empathy. In our samples, Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.77.

Self-integrity

The self-integrity scale was designed by Sherman et al. (Reference Sherman, Cohen, Nelson, Nussbaum, Bunyan and Garcia2009) to measure perceptions of self-integrity. A previous study has tested the reliability and validity of the self-integrity scale in Chinese older adults and has proven that the scale has good reliability and validity in Chinese older adults (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Bai, Zhang and Lin2021a). The scale contained eight items (e.g. ‘I have the ability or skill to deal with various problems on the road of life’) and participants indicated their agreement with each item on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Scores of all items were averaged to create a self-integrity index. Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-integrity. Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.75 in the current study.

Procedure

Data collection was conducted from April 2018 to May 2019, and older adults were invited to participate in the face-to-face survey-based study managed by trained students of psychology. Participants were recruited through advertisements, specifically by distributing leaflets and displaying banners in the square or activity rooms, given that these areas have a high flow of people. To control sampling bias, we proactively introduced our face-to-face survey-based study to older adults in other areas of the community and asked them whether or not they would like to participate. Meanwhile, we welcomed older adults who had completed the questionnaire to invite their friends or colleagues, who may also be interested in joining our survey. The participants completed the questionnaires independently in a quiet area with minimal distractions. When needed, they could approach the research assistant if they had any questions. For illiterate or presbyopia older adults who cannot see clearly, trained postgraduate students in psychology read the questions and asked older adults to provide their answers verbally. Older adults were informed that their participation was voluntary and could be terminated at any time if they wished. Each participant signed an informed consent form and received a gift as a reward thereafter. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Shaanxi Normal University.

Data analysis

Firstly, we conducted Harmen's one-factor test to check for common method variance. Secondly, preliminary data were analysed using SPSS 25.0 to determine the correlation amongst variables. Thirdly, we used Hayes' (Reference Hayes2017) SPSS macro-PROCESS (Model 6) with 5,000 bias-corrected bootstraps to examine the indirect effects of sense of coherence and empathy. According to Edwards and Lambert (Reference Edwards and Lambert2007), the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method is the best method to determine mediation. We examined the individual mediating roles of sense of coherence and empathy, as well as their serial mediating role, in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity through multiple linear regressions by using the SPSS macro-PROCESS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2017).

Results

Common method variance

We conducted Harmen's one-factor test to check for common method variance. In this procedure, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used, and all variables were entered into an EFA (principal component factor analysis with no rotation). If a single factor arises from the factor analysis or one general factor accounts for most of the variance (>40%), then there is an amount of common method variance. In the present study, the results showed that EFA resulted in 13 factors with eigenvalues above 1. The first factor accounted for only 19.36 per cent of the total variance, which was considerably below 40 per cent, indicating that common method variance was not of significant concern in this study.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

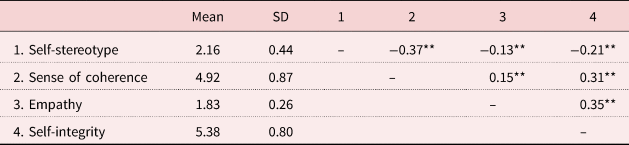

The means, standard deviations and correlations amongst variables are presented in Table 2. All variables were closely related to one another. As shown in Table 2, self-integrity was significantly correlated with self-stereotype, sense of coherence and empathy, whilst self-stereotype had a significant negative correlation with sense of coherence and empathy, and sense of coherence had a significant positive correlation with empathy as well. These results indicated that the hypothesised model, which explains individual mediating roles and linkage mediating roles of sense of coherence and empathy in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity, met the requirements that the mediating model requires that included variables in each path should be significantly correlated with each other, as suggested by MacKinnon et al. (Reference MacKinnon, Fairchild and Fritz2007).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of variables

Notes: N = 825. SD: standard deviation.

Significance level: ** p < 0.01.

Mediating effects

Self-stereotype and self-integrity

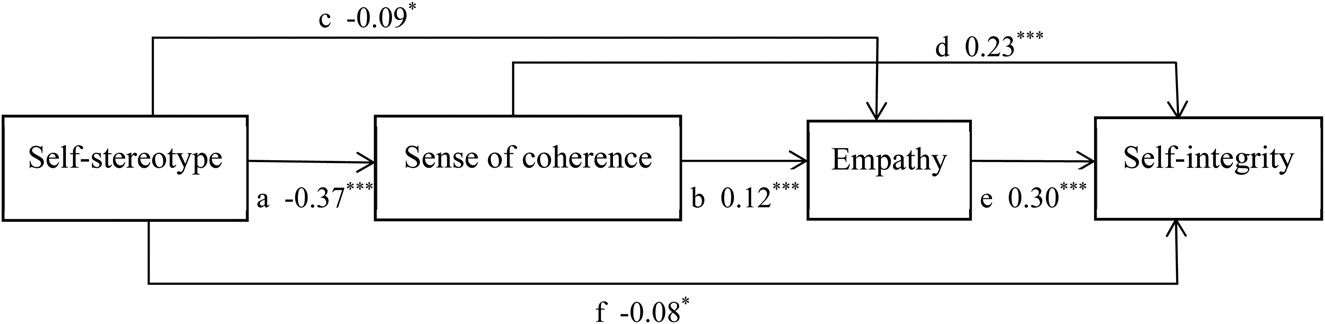

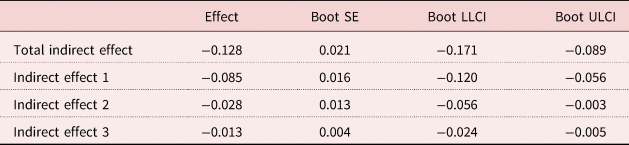

The results of the chain mediating effect on sense of coherence and empathy are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2, self-stereotype can significantly predict self-integrity (β = −0.08, standard error (SE) = 0.034, p < 0.05), indicating that the direct effect was significant. Hence, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Figure 2. Mediating effect of sense of coherence and empathy on the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity.

Notes. a = path from self-stereotype to sense of coherence, b = path from sense of coherence to empathy, c = path from self-stereotype to empathy, d = path from sense of coherence to self-integrity, e = path from empathy from self-integrity, f = path from self-stereotype to self-integrity. The effects are reported in standardised values. Significance levels: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

Table 3. Indirect effect of sense of coherence and empathy

Notes: N = 825. Effect: standardised beta. Indirect effect 1 is self-stereotype → sense of coherence → self-integrity. Indirect effect 2 is self-stereotype → empathy → self-integrity. Indirect effect 3 is self-stereotype → sense of coherence → empathy → self-integrity. Boot SE, Boot LLCI and Boot ULCL are estimated standard error, 95% confidence interval lower and 95% confidence interval upper through the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method used for testing indirect effects; 95% confidence intervals do not overlap with zero.

Mediating effect of sense of coherence

Figure 2 shows that self-stereotype can significantly negatively predict sense of coherence (β = −0.37, SE = 0.033, p < 0.001). Sense of coherence can significantly positively predict self-integrity (β = 0.23, SE = 0.034, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of sense of coherence was significant (β = −0.085, SE = 0.016, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.120, −0.056) (see Table 3). Zero was not included in the interval, indicating that the mediating effect was significant. That is, sense of coherence played a mediating role in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

Mediating effect of empathy

As shown in Figure 2, self-stereotype can negatively predict empathy (β = −0.09, SE = 0.038, p < 0.05) and empathy can positively predict self-integrity (β = 0.30, SE = 0.032, p < 0.001). Table 3 shows the mediating effect of empathy (β = −0.028, SE = ;0.013, 95% CI = −0.056, −0.003). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Serial mediating effects of sense of coherence and empathy

We also tested the serial mediating effects of sense of coherence and empathy. The results obtained (β = −0.013, SE = 0.004, p < 0.01, 95% CI = −0.024, −0.005) indicate that the chain mediation effects of sense of coherence and empathy were significant. Hence, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

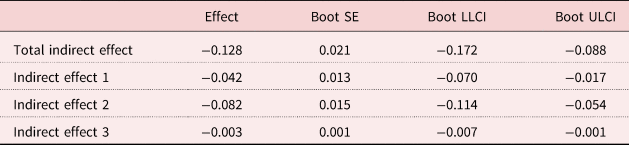

To confirm the sequence of the two mediators in the hypothesised model, we also established another competing model (i.e. self-stereotype → empathy → sense of coherence → self-integrity) that includes a variation of the proposed chain mediation pathway. In this model, the order of the mediators was reversed. That is, self-stereotype in the competing model was predicted to be associated with empathy, followed by sense of coherence and self-integrity. The newly established model yielded a marginal significant chain mediation effect (β = −0.003, SE = 0.001, 95% CI = −0.007, −0.001) (for details, see Table 4). However, the chain mediation effect of this competing model is smaller than that of the hypothesised model (i.e. self-stereotype → sense of coherence → empathy → self-integrity), which was included originally (β = −0.013, SE = 0.004, 95% CI = −0.024, −0.005). Additionally, Hagquist and Stenbeck (Reference Hagquist and Stenbeck1998) indicated that R 2 could be used to assess the goodness of fit for a linear regression model; the higher the R 2, the better the model fits the data. Therefore, the present study used R 2 as criterion for model comparison. Given that R 2 in this study reflects the model fitting of the relationship between the independent and mediation variables with the dependent variable, the results for the competing and hypothesised models should be the same. On this basis, we want to clarify which variable of sense of coherence and empathy is more suitable as the first mediating variable. Thus, we compared R 2 in the model of self-stereotype acting on sense of coherence and R 2 in the model of self-stereotype acting on empathy. Comparison results of the model showed that R 2 of sense of coherence as the first mediating variable in the hypothesised model was 0.137, whilst R 2 of empathy as the first mediating variable in the competing model was 0.019. That is, sense of coherence is more appropriate as the first mediating variable. The preceding results show that the hypothesised model was preferable.

Table 4. Indirect effect of empathy and sense of coherence

Notes: N = 825. Effect: standardised beta. Indirect effect 1 was self-stereotype → empathy → self-integrity. Indirect effect 2 was self-stereotype → sense of coherence → self-integrity. Indirect effect 3 was self-stereotype → empathy → sense of coherence → self-integrity. Boot SE, Boot LLCI and Boot ULCI are estimated standard error, 95% confidence interval lower and 95% confidence interval upper through bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method used for testing indirect effects; 95% confidence intervals do not overlap with zero.

Discussion

This study integrated self-stereotype, sense of coherence, empathy and self-integrity into one model, and systematically examined the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity, the mediating roles of sense of coherence and empathy. The results showed a close relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity. Age-related self-stereotypes are negatively related to self-integrity of older adults. Sense of coherence and empathy played mediating roles in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity. The results of this study are helpful to understand the relationship between self-stereotype on self-integrity and the related intervening mechanism.

The current study demonstrated that self-stereotype negatively correlated with self-integrity, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (e.g. Livingston and Boyd, Reference Livingston and Boyd2010). The results, along with that of other research, showed that self-integrity buffers the rise and fall of self-feelings in response to stereotype threats (e.g. Čehajić-Clancy et al., Reference Čehajić-Clancy, Effron, Halperin, Liberman and Ross2011). Only a few studies have examined the associations between self-stereotype and self-integrity, indicating that stigma harms self-integrity and leads to self-depreciation. People may avoid information on psychological help because of self-stereotype effects associated with help-seeking information that threatens self-integrity (Lannin et al., Reference Lannin, Vogel, Brenner, Abraham and Heath2016). The present research provided evidence that self-integrity is affected by the way people perceive themselves in stigmatised situations or behaviour. The results of this study are helpful to answer a certain important question on the effect of self-stereotype on self-integrity.

A test of the serial mediation model from self-stereotype to self-integrity provided evidence that the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity is mediated by sense of coherence and empathy. According to previous studies, one's sense of coherence is more of a mediating factor than a direct influencing factor on one's physical and mental health (Moksnes et al., Reference Moksnes, Espnes and Haugan2013). The results of the current study corresponded to those of previous studies and showed that stigma-related stressors are associated with a diminished sense of coherence (Lundberg et al., Reference Lundberg, Hansson, Wentz and Bjorkman2009). Other comparable findings reported by Suresky et al. (Reference Suresky, Zauszniewski and Bekhet2008) showed that sense of coherence mediates the effects of negative health outcomes as stigmatised behaviour and enhanced self-integrity. This result indicated that a stronger sense of coherence ameliorates the adverse effects of internalised stigma and fosters self-integrity. Thus, our findings were consistent with those of Wells and Kendig (Reference Wells and Kendig1999), and emphasised the important role of sense of coherence in a negative relationship with self-stereotype and positive association with self-integrity. Our mediation analyses clearly showed that sense of coherence has significant negative and positive relationships with self-stereotype and self-integrity, respectively. In an adverse environment or under stressful events, a high level of sense of coherence can reportedly allow individuals to adopt a markedly effective coping style and reduce negative influence on mental health by increasing self-integrity (Kleiveland et al., Reference Kleiveland, Natvig and Jepsen2015). According to Antonovsky's (Reference Antonovsky1987) salutogenesis theory, sense of coherence could be considered a positive mental resource because it reveals how people perceive life and use their resources to cope with stressors. Antonovsky (Reference Antonovsky1987, Reference Antonovsky1979) also claimed that sense of coherence is an internal experience, which gradually develops in youth to a relatively lasting and stable quality after the age of 30. Similarly, individuals establish negative perceptions of ageing in early life; as they grow older, they gradually incorporate these negative perceptions into their own views, thereby forming self-stereotyping (Rothermund and Brandtstädter, Reference Rothermund and Brandtstädter2005). Self-stereotyping and sense of coherence can be inferred to seemingly have similar lifecourse development trajectories. Additionally, the strength of sense of coherence is continuously influenced by external events and internal reactions to these events (Suominen, Reference Suominen1993). Thus, individuals are confronted with stereotypes of ageing and subsequently internalise self-stereotyping into ageing, thereby affecting the level of sense of coherence. By contrast, individuals with minimal sense of coherence for self-stereotype impact will face problems in responding, thereby negatively impacting their mental health (Kleiveland et al., Reference Kleiveland, Natvig and Jepsen2015).

Sense of coherence is the cornerstone of salutogenic theory and also a protective element for individuals' development under the influence of external environment by mediating the effects of the environment on them (Richardson and Ratner, Reference Richardson and Ratner2005). Individuals with a strong sense of coherence think their world is manageable, comprehensible and meaningful. They make good use of existing and potential resources to deal with external threats (Antonovsky, Reference Antonovsky1987). Given that sense of coherence is an individual's important psychological construct to develop self-system, the sense of coherence plays a vital role in essential resources such as agency and hardiness (Antonovsky, Reference Antonovsky1987), which enables the self-system to perceive and interpret external events and the environment, and flexibly adapt resources. People with a strong sense of coherence are better able to adapt and respond to the environment to sustain self-integrity (Silver, Reference Silver2013). A strong feeling of coherence can help people adopt a more active and effective coping style and prevent negative effects on mental health when they are in a stressful setting or confronted with stressful circumstances. This study found that although the sense of coherence of older adults would be relatively affected negatively in the face of negative self-stereotype, the sense of coherence of older adults could also buffer the negative impact, thereby having a positive impact on the empathy and self-integrity of older adults.

However, our results also showed that empathy is helpful to the development of self-integrity. This research clearly showed that empathic induction can influence and reduce stereotypical perceptions, consistent with the results of previous studies (Galinsky and Moskowitz, Reference Galinsky and Moskowitz2000). Similarly, high levels of self-stereotype diminished empathic concern in older adults. Another study has shown that individuals who face mental health difficulties are frequently stigmatised owing to their association with a specific psychiatric label or perceived membership within this marginalised group with low empathy (Byrne, Reference Byrne2000). Empathic concern plays a vital mediating role in supporting those suffering from some stereotypical attitudes as it generally does for helping others (Batson and Shaw, Reference Batson and Shaw1991), and is presumed to foster self-integrity on social norms and ethics (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Shepard, Eisenberg, Fabes and Guthrie1999). These findings support Erikson's (Reference Erikson1968) postulate that empathy is a foundation of responsive relationships that form a vital part of positive development for self-integrity. Evidence has supported the idea that empathic people are more self-integrated than those who have a relative lack of empathy (Blair, Reference Blair, Arsenio and Lemerise2010; Zelazo and Paus, Reference Zelazo and Paus2010). Our mediating analysis clearly showed that empathy is negatively associated with self-stereotype and positively associated with self-integrity and plays the mediating role between self-stereotype and self-integrity.

Findings of the current study suggested that the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity may be indirect. One study has investigated that sense of coherence and empathy are also direct predictors of socio-psychological balance (Linley and Joseph, Reference Linley and Joseph2007). The current study identified positive predictors of growth, including sense of coherence and empathy, which play crucial roles in maintaining a positive lifestyle with higher self-integrity (Linley et al., Reference Linley, Joseph and Loumidis2005). The results of mediation analysis showed a clear view of ageing that sense of coherence is a strong predictor of empathy, which is consistent with previous studies (Pålsson et al., Reference Pålsson, Hallberg, Norberg and Björvell1996; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Zhang and Li2013). Older adults with a high sense of coherence score were more empathetic in their relationships with others than those with a low sense of coherence. According to Antonovsky's (Reference Antonovsky1987) salutogenesis theory, the possible reason is that high general comprehensibility enables people to have a deep understanding of other individuals' problems. Individuals with a high sense of coherence particularly have cognitive and behavioural methods that enable them to adjust to challenging conditions (Mowlaie et al., Reference Mowlaie, Mikaeili, Aghababaei, Ghaffari and Pouresmali2017) to foster self-integrity. This idea was consistent with our results that sense of coherence and empathy interrelate with each other and enhance self-integrity. Hence, the chain relationship from sense of coherence to empathy plays a serial mediating effect on the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity.

Implication and limitation

This study has important theoretical implications because it extends the research on the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity. Numerous studies have examined the associations amongst self-stereotype, sense of coherence, empathy and self-integrity (Blair, Reference Blair1995; Corrigan and Kleinlein, Reference Corrigan, Kleinlein and Corrigan2005; Sherman and Cohen, Reference Sherman and Cohen2006). However, only a few studies have shown how self-stereotype affects self-integrity and what roles sense of coherence and empathy play in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity in older adults. The results of the current study revealed that self-stereotype can be negatively associated with self-integrity, although sense of coherence and empathy played the roles of mediators in the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity in older adults. This result extends and enriches the theoretical system on the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity.

This study also has important practical implications for interventions aimed at improving older adults' self-integrity. The findings of this study showed that self-stereotype can influence sense of coherence, empathy and self-integrity, indicating that self-stereotype has negative effects on promoting individuals' positive psychological health or self-integrity. Therefore, adopting a positive and consistent sense of coherence has a strong basis in the suitability of physical, social and cognitive resources. Additionally, knowing what other people feel is important in all stages of life. Empathic reactions are vital for our social relationships and wellbeing because lower empathy is linked with reduced social functioning (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Henry and Von2008). Thus, if self-stereotypes start affecting older adults' mental health, then three key elements of wellbeing, namely sense of coherence, empathy and self-integrity, will help to maintain their lifestyle.

Certain limitations and further research directions should be noted in this study. Firstly, this study adopted a cross-sectional approach, which cannot determine the causal relationship amongst variables. In the future, a longitudinal study design could be used. On the bases of discussions of the related variables' longitudinal relationships, we can also discuss the cause–effect relationship amongst variables, thereby providing a clear basis for the development of self-integrity research. Secondly, this study relied on the use of self-report measures, which are susceptible to self-reporting biases. Future studies could introduce some other effective physical indicators that could reflect the levels of self-integrity in older adults.

Conclusion

This study explored how self-stereotypes are associated with self-integrity in older adults. The results showed that self-stereotype is negatively associated with self-integrity. Additionally, sense of coherence and empathy played important roles in mediating the relationship between self-stereotype and self-integrity. The findings are crucial in answering the question of how self-stereotypes are associated with the self-integrity of older adults. That is, sense of coherence and empathy played vital roles as mediators, which promote positive self by mitigating the adverse effects of self-stereotype in older adults. On the basis of the current results, we can conclude that this research provides practical awareness of promoting self-integrity.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (17BSH153).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures completed in this study involving individual participants were in accordance with ethical standards. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Shaanxi Normal University. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.