Introduction

Food insecurity,Footnote 1 defined as “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways” (Anderson, Reference Anderson1990), is a relatively nascent but rapidly evolving field of research.

Over the past half century, food insecurity as a construct, a measure, and a defined public health issue has evolved from when early civil rights and anti-poverty activists first put “hunger” on the public and political radar in the United States (Poppendieck, Reference Poppendieck1998; Wunderlich & Norwood, Reference Wunderlich and Norwood2006). Moral public outrage was also palpable in Canada around that time, during an era characterized by retraction of social security programs and social and welfare services (Poppendieck, Reference Poppendieck1998). Early qualitative researchers began to study hunger among low-income families, and started to conceptualize the phenomenon of food insecurity and the conditions that allow it to persist in industrialized countries (Radimer, Olson, Campbell, Reference Radimer, Olson and Campbell1990). After a period of debate, the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) was created to capture different dimensions of the experience of food insecurity, including quantity, quality, and psychological and social acceptability (Anderson, Reference Anderson1990). Until the design of the HFSSM and its implementation in national population level surveys, the survey tools used to capture food insecurity were inconsistent and incomplete, resulting in incomparability across study contexts and no real “big picture” view of the scope or scale of the problem (Anderson, Reference Anderson1990; Radimer, Reference Radimer2002).

Since then, over the past few decades, food insecurity as an issue has been taken up by different groups of academic and government researchers, community food advocates, public health authorities, nutritionists, and medical physician groups. Accordingly, food insecurity has been explored and connected to a plethora of adverse immediate and long-term outcomes, including nutritional deficiencies, psychosocial consequences, and health outcomes, as well as environmental and socio-economic conditions (Gundersen & Ziliak, Reference Gundersen and Ziliak2015; Gundersen & Ziliak, Reference Gundersen and Ziliak2018).

However, the literature on food insecurity and aging continues to be limited, and this is likely in part due to the relatively lower rates of food insecurity among older people as compared to younger people (Che & Chen, Reference Che and Chen2001). Researchers point to public policy as the most important intervention level for food insecurity (Emery, Fleisch, McIntyre Reference Emery, Fleisch and McIntyre2013a; McIntyre, Dutton, Kwok, & Emery, Reference McIntyre, Dutton, Kwok and Emery2016; Tarasuk, Mitchell, Dachner, Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner2016). Indeed, food insecurity maps closely onto household income, and food insecurity rates are lowest in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries with the strongest social welfare expenditures (Riches, Reference Riches2018). And among those countries, the lowest rates of food insecurity are experienced by older people, which is largely attributable to strong social entitlements for older people (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Dutton, Kwok and Emery2016; Nord, Reference Nord2002).

However, there are a number of justifications for investigating the issue of food insecurity among older people specifically. To begin with, some researchers have voiced concerns about measurement, and point to the complexity of food insecurity among older people and question the adequacy of the HFSSM, which was initially developed for younger populations (Radimer, Olson, Green, Campbell, & Habicht, Reference Radimer, Olson, Greene, Campbell and Habicht1992), to fully capture the phenomenon among older people (Quandt, Arcury, McDonald, Bell, & Vitolins Reference Quandt, Arcury, McDonald, Bell and Vitolins2001; Sahyoun & Basiotis, Reference Sahyoun and Basiotis2001).

Furthermore, of the limited research that does exist, much has been undertaken according to varied research traditions from the fields of nutrition, public health, economics, agriculture, and gerontology. Different fields of research are underpinned by differing epistemological assumptions. Exploring the same issue (food insecurity) from different paradigmatic positions has likely resulted in a fractured literature base without clear and cohesive research directions moving forward.

Additionally, the scarce research on food insecurity among older people that does exist arises from different national and political contexts. Research agendas are in part shaped by the differing political economies, normative cultures around aging and treatment of the aged, as well as the types of social assistance and food assistance that are in place in different countries. Differences in how food insecurity is defined and measured among older people present challenges in terms of comparing food insecurity among older people against a backdrop of changing demographic and social conditions, including aging populations alongside the hollowing out of social safety nets (Emery, Fleisch, & McIntyre Reference Emery, Fleisch and McIntyre2013b; McIntyre & Rondeau, Reference McIntyre, Rondeau and Raphael2009). This scenario endangers the taken-for-granted low levels of food insecurity among older people.

Lastly, much of this research seems to be rooted in an orthodoxy fixated on old age as opposed to aging, that naturalizes old age decline. Food insecurity is a serious and urgent public health issue, and scholarship on aging has much to offer in terms of concepts and critiques to help better shape the research agenda on food insecurity moving forward.

The purpose of this study was to bring together the disparate literature concerning food insecurity among older people. Our research objectives were to (a) characterize the methodological, empirical, and conceptual contributions of each study; and to (b) thematically analyse the rationale and implications underpinning each study, as well as the conceptual mechanisms hypothesized to connect aging to food insecurity. The goals of this research were to clarify some of the tendencies and contradictions of this broader literature as a whole, as well as to prompt more critical examination of the ways that aging is relevant to food insecurity research.

Methods

Methodological Approach

Considering the paucity of food insecurity literature pertaining to older people, we determined that a scoping study methodology, as described by Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) and later refined by Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010) and Colquhoun et al. (Reference Colquhoun, Levac, O’Brien, Straus, Tricco, Perrier and Moher2014), would best allow us to address our above-described study aims and objectives. We did not set out to appraise the quality of individual studies, but rather sought to generate an overall picture of the gaps and limitations of the particular intersecting scholarship of food insecurity and aging (Armstrong, Hall, Doyle, & Waters, Reference Armstrong, Hall, Doyle and Waters2011).

Scoping studies are increasingly used for reviewing emerging evidence in which limited research makes it difficult to undertake a systematic review (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005), especially where an area is complex or has not previously been reviewed comprehensively (Mays, Pope, & Popay, Reference Mays, Pope and Popay2005). We drew from the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) to give structure and rigour to the iterative and generative aspects of our methodology, including devising criteria post hoc alongside increasing familiarity with the literature. The stages initially proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) formed the basis of the methodological framework for a scoping study, and included the following: (a) identifying the research question, (b) identifying relevant studies, (c) selecting the studies, (d) charting the data, (e) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Identification of the Research Question

Food insecurity research pertaining to older people has not previously been reviewed. The research we undertook to examine food insecurity among older people derives from different fields of research, and thus, in the absence of previous reviews, and considering the scarcity and scattered nature of this research, we determined that the most appropriate elemental research question to begin with would be: How is food insecurity being studied among older adults? With this question, we were able to set more restrictive parameters for meeting our specific objectives once we gained a better sense of the broader literature.

Identification of Relevant Studies

We began in the fall of 2015 by collating a small selection of relevant studies. Preliminary searching of basic terms helped orient us with the literature and the contributing fields, as well as help us gain a better sense of the diversity of key search terms. We hand-searched the reference lists of each article from this early sample, and reviewed online publication lists of the most visible researchers. Next, we consulted with a research librarian to select relevant health sciences and social sciences databases and to confirm the appropriate search parameters for each database. These consultations led us to identify key journals (to be hand-searched), to establish a search strategy, and to develop an initial set of key search terms. Additionally, we searched the Cochrane online database for existing reviews on or related to the subject, whereby we discovered one protocol related to our topic which also helped to inform the search strategy (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Kristjansson, Harris, Armstrong, Cummins, Black and Lawrence2010). Early database searches and mining of reference lists led us to circle back to re-refine the search terms, and begin to devise inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study Selection

Eligibility Criteria

Research studies were considered for inclusion if they prominently and predominantly focused on food insecurity and older people. The study population of “older” adults was conceptualized as being whatever age categories or thresholds researchers defined as being older. For studies that examined food insecurity across age categories, we included studies in our work if the older populations were prominently featured in the analyses and discussion. Because we sought to explore the issue more broadly, we included only studies that examined food insecurity among non-institutionalized older people. Studies that used food insecurity as a variable, or determinant of another health outcome, and did not discuss the possible determinants of food insecurity or mechanisms through which food insecurity leads to that outcome, were not included.

Studies that exclusively studied rural food insecurity were not included, as these studies tended to focus on the unique aspects of food insecurity specific to rural settings. Due to the differing nature and experiences of food systems in developing countries, we considered only those studies that examined food insecurity in developed (or more-developed countries). To establish the current state of the scholarship with respect to our research question overall, we limited search returns to peer-reviewed journal articles. These could include qualitative or quantitative methods, and observational, experimental, or literature review studies. Accordingly, the following documents were not included in the review: conference abstracts, letters, commentaries, editorials, or theses.

Search Strategy and Identification of Studies

The following selection of social sciences and health sciences databases were accessed from May to July 2016: CINAHL, EMBASE, ProQuest Central, Web of Science, IBSS (International Bibliography of the Social Sciences), HealthSTAR, GEOBASE, MEDLINE, OVID, and Scholars Portal.

We searched the databases independently by key terms as well as subject headings. Note that variants and wild card truncations were also used. Wherever possible, we placed search parameters on the databases to limit searches to (a) human populations, (b) English language, (c) journal articles, (d) peer-reviewed studies, (e) urban settings, and (f) age limits (older than age 60 or 65 years). Subject headings included food security or food insecurity, as some databases differentiated with relevant content between these two concepts. We developed key search terms to describe the issue of food insecurity (food security, food insecurity, food-related hardship, food access, food environment, food insufficiency) and the population (elderly, older, senior, aged).

The reviewer protocol was generative and iterative. We independently searched each database by key search terms and subject headings. Afterward, we reconvened to compare numbers and a sample of titles to confirm their exclusion frames.

Next, we combined titles and removed duplicates. Any discrepancies in titles were discussed to ensure consistency and exhaustiveness of the initial catchment. During the second stage, we reviewed abstracts and included them if older adults were a main focus of the research study and prominently focused in the methods and findings of the study. We found that when studies lacked a clear focus on older people (i.e., if, in the methods, age groups were collapsed) that the findings were not differentiated between age groups and thus there was very little consideration of age with respect to the broader inquiry. Additionally, we excluded abstracts if they did not satisfy the initial search parameters (due to differing capabilities of each database). For example, many studies were excluded due to the same spelling of aged: “aged 4–9 years old” versus aged as in “people who are aged”. During the third stage, we each reviewed sets of the full-text articles and subsequently discussed the broader collection of studies.

In reading the whole article, we decided to exclude studies that focused on program evaluation or cost-comparison of community-based food programs and services for older adults. We made this decision because we found these studies to examine food insecurity among older people in an indirect or secondary way and offered few insights into the relevance of aging to food insecurity as an issue. Similarly, there were a few studies that inexplicably examined food insecurity as a mediator or moderator of another health outcome, and for the same reasons, we excluded those at this point as well.

Charting the Data

The data extraction was a two-stage approach – descriptive and analytic – to characterize the collection of studies. To begin, each study was described according to methodological, empirical, and conceptual contributions. Methodologies were described according to research approach, sample size, study design, food insecurity measurement, and age definition. Empirical contributions were condensed to include the main findings of the research study, including qualitative themes, for example, or positive, negative, or null relationships relating to food insecurity. Next, we more closely examined the conceptual contributions. Studies were gleaned for theoretical frameworks, references to theory, conceptual models, and explicit or hypothetical mechanisms for how food insecurity might relate to aging. Additionally, we pulled the stated study rationale and research implications from each study, from introduction sections, and introduction and discussion sections respectively. Separate spreadsheets were maintained for each of the ways that studies were described (methodological, empirical, conceptual), were organized in tabular form, and from there we distilled them to form the basis of the analytic stage of this study.

Collating, Summarizing, Reporting the Results

Different disciplines have different philosophical paradigms, and taken-for-granted ontological, epistemological axiological and methodological assumptions. Because the literature on food insecurity and aging has been taken up by various disciplines, it was important for us to acknowledge the potential differences in cultures of inquiry from which our collection of studies was drawn. Therefore, we found it prudent to tackle our guiding research question using qualitative synthesis, to “create a product that is more than the sum of its parts” (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Reference Barnett-Page and Thomas2009). We determined that thematic analysis would best allow us to offer a coherent synthesis of the current state of the literature (Thomas & Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008), to more fundamentally address the research question how is food insecurity being studied among older people. We used rationale, implications, and implicitly or explicitly stated mechanisms connecting aging to food insecurity to serve as evidence of philosophical assumptions underlying the research inquiry of each study. Close reading and re-reading of the study rationale, research implications, and hypothetical mechanisms rendered a selection of relevant text fragments. Constant comparison of these fragments within the articles, and organization into a table, allowed for them to remain connected to the original manuscript context. Thematic analysis of this content was performed, whereby we grouped text fragments into sub-themes, which were then constructed into themes (Thomas & Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008).

Results

Collection of Studies

Database searching yielded an initial catchment of 2,041 potential articles. Of these, 35 studies met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Three additional studies that were included in the final review collection resulted from preliminary searching and hand-searching reference lists. Inter-rater reliability of the initial titles to the final collection of studies was calculated as Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (Kappa = 0.699, SE: 0.051). Studies were described by title, study location, research method, main study findings directly pertaining to food insecurity and older people, and theoretical references (Table 1).

Figure 1: Search results flowchart

Table 1: Overview of studies included in the current review (each study was described by methodological approach, main findings [+: relationship found. -: no relationship found. ‘o’: inconclusive relationship. ‘rr’ = reported rate], and theoretical references or frameworks)

FI = food insecurity; FS = food security; FVI = fruit and vegetable intake; PA = physical activity; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Characterization of Study Collection

All studies were conducted from the year 1996 to 2016. Study location was a decidedly relevant detail, as national context gives insight into the different social policies and programs that impact food security into older ages at a population and individual level. Twenty-eight of the studies were conducted in the United States; six, in Australia; three, in Canada; and one was conducted in the United Kingdom. Twenty-nine studies were conducted using a quantitative approach, eight studies used qualitative methods, and one study employed mixed methods.

Although most studies examined food security and older people more broadly, some studies, which tended to be smaller scale and/or employ qualitative methods, exclusively focused on the particular vulnerability of sub-groups of older people, including low-income (Emery et al., Reference Emery, Fleisch and McIntyre2013b; Green-LaPierre et al., Reference Green-LaPierre, Williams, Glanville, Norris, Hunter and Watt2012; Guthrie & Lin, Reference Guthrie and Lin2002; Johnson, Sharkey, & Dean, Reference Johnson, Sharkey and Dean2011; Keller, Dwyer, Senson, Edwards, & Edward, Reference Keller, Dwyer, Senson, Edwards and Edward2006; Nord & Kantor, Reference Nord and Kantor2006; Pierce, Sheehan, & Ferris, Reference Pierce, Sheehan and Ferris2002), gender (Green-LaPierre et al., Reference Green-LaPierre, Williams, Glanville, Norris, Hunter and Watt2012; Klesges et al., Reference Klesges, Pahor, Shorr, Wan, Williamson and Guralnik2001; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Sheehan and Ferris2002), race (or culture) (Radermacher, Feldman, & Bird, Reference Radermacher, Feldman and Bird2010a; Radermacher, Feldman, Lorains, & Bird, Reference Radermacher, Feldman, Lorains and Bird2010b; Sharkey & Schoenberg, Reference Sharkey and Schoenberg2005), disability (Brewer, Catlett, Porter, Lee, & Hausman, Reference Brewer, Catlett, Porter, Lee and Hausman2010; Klesges et al., Reference Klesges, Pahor, Shorr, Wan, Williamson and Guralnik2001; Lee & Frongillo, Reference Sun Lee and Frongillo2001), chronic disease status (Brewer et al., Reference Brewer, Catlett, Porter, Lee and Hausman2010; Sharkey, Reference Sharkey2005), being homebound (Sharkey, Reference Sharkey2005; Sharkey & Schoenberg, Reference Sharkey and Schoenberg2005), and living alone (Quine & Morrell, Reference Quine and Morrell2005). Study findings mainly pertained to individual, interpersonal, and environmental risk factors or predictors of food insecurity among older people. Many of the observational studies reported varying prevalence rates of food insecurity within their respective study populations (Fitzpatrick, Greenhalgh-Stanley, & Ver Ploeg, Reference Fitzpatrick, Greenhalgh-Stanley and Ver Ploeg2015; Russell, Flood, Yeatman, & Mitchell, Reference Russell, Flood, Yeatman and Mitchell2014; Woltil, Reference Woltil2012).

Despite such procedural differences, there was consistency in co-variates used across studies. Analyses tended to concentrate on individual-level variables, with an overall emphasis on socio-demographic factors: age, gender, ethnicity, education, marital status, income level, source of income, housing tenure, and living arrangements. There was also considerable focus on the role of social support in sustaining food security for older people (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Gallo, Giunta, Canavan, Parikh and Fahs2011; Frongillo, Valois, & Wolfe, Reference Frongillo, Valois and Wolfe2003; Green-LaPierre et al., Reference Green-LaPierre, Williams, Glanville, Norris, Hunter and Watt2012; Keller et al., Reference Keller, Dwyer, Senson, Edwards and Edward2006; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Sheehan and Ferris2002; Radermacher et al., Reference Radermacher, Feldman, Lorains and Bird2010b; Woltil, Reference Woltil2012).

The methods of eight studies, including three quantitative and five qualitative studies, centred on the importance of examining the relationship between food insecurity and other factors longitudinally (Alley et al., Reference Alley, Soldo, Pagan, McCabe, deBlois, Field and Cannuscio2009; Bhargava & Lee, Reference Bhargava and Lee2016; Bhargava, Lee, Jain, Johnson, & Brown, Reference Bhargava, Lee, Jain, Johnson and Brown2012; Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Greenhalgh-Stanley and Ver Ploeg2015; Frongillo et al., Reference Frongillo, Valois and Wolfe2003; Green-LaPierre et al., Reference Green-LaPierre, Williams, Glanville, Norris, Hunter and Watt2012; Russell, Flood, Yeatman Wang, & Mitchell, Reference Russell, Flood, Yeatman, Wang and Mitchell2016; Sattler & Lee, Reference Sattler and Lee2013; Sharkey, Reference Sharkey2005). Other studies made use of cross-sectional data, while citing the importance of understanding the direction and the dynamics of the relationship between food insecurity and aging (Bengle et al., Reference Bengle, Sinnett, Johnson, Johnson, Brown and Lee J2010; Brewer et al., Reference Brewer, Catlett, Porter, Lee and Hausman2010; Goldberg & Mawn, Reference Goldberg and Mawn2014; Klesges et al., Reference Klesges, Pahor, Shorr, Wan, Williamson and Guralnik2001; Sharkey, Reference Sharkey2004; Sharkey, Reference Sharkey2005; Temple, Reference Temple2006). For example, Goldberg & Mawn (Reference Goldberg and Mawn2014) suggested that longitudinal studies would be useful in examining the relationships between cause and effect of the predictors of food insecurity among older people, which could then inform intervention studies designed to target groups and sub-groups at highest risk of food insecurity. Klesges et al. (Reference Klesges, Pahor, Shorr, Wan, Williamson and Guralnik2001) examined potential relationships between food insufficiency and poor health and well-being among elderly disabled women, but called for longitudinal data to ascertain the role of financial difficulty of their acquiring food.

Upon closer examination of methodologies, differences in terminology and definitions of food insecurity were found between studies (Table 2). Although many studies employed the 1998 Life Sciences Research Office definition for food insecurity, or some shortened variations thereof, several studies used related terminology – food and material hardship, food insufficiency, food disadvantage, nutrition insecurity, food adequacy, food access – interchangeably with food insecurity and alongside food insecurity measures. Most common measures of food insecurity included the full-version and modified versions of the U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module (U.S. HFSSM). Some researchers included measures that were adapted to better capture the unique experience of food insecurity among older people (for example, age-related factors such as physical access to food stores, or physical limitations in preparing and cooking meals).

Table 2: Overview of methodological approaches in the current collection of studies (studies are methodologically described by data set, sample size, study design, methodological approach, food insecurity study instrument or definition, and definition of age)

NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey; NSENY = Nutrition Survey of the Elderly in New York

a Food insecurity definition most commonly cited “state when the availability of or ability to acquire nutritionally adequate and safe food in socially acceptable ways is limited or uncertain”, and food security definition most commonly cited “having access at all times to enough food for an active and healthy lifestyle”.

Other researchers employed combinations of food insecurity measures, both of which introduced variability in terms of thresholds for severity of food insecurity that were found to be very consistent across studies that employed the standard versions of the U.S. HFSSM.

Many researchers were able to base their inquiries on large, rich, and existing data sets that included these validated versions of the U.S. HFSSM (i.e., NHANES, Current Population Survey, National Health Interview Survey in the United States, and in Canada, the Canadian Community Health Survey). Because Australia does not formally monitor food insecurity, the studies coming out of Australia had the most limited consistency in food insecurity definition and instrumentation. There was variability across studies in terms of the reference period of the measurement, with some measures asking survey respondents to report on their food insecurity over the past 2 years, 12 months, 6 months, or 30 days, and other studies not indicating the reference period.

There was considerable variability in how old age was operationalized. Although many studies defined old age as being 55, 60, or 65 years of age and older, some included study populations as young as 49 years (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Flood, Yeatman and Mitchell2014; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Flood, Yeatman, Wang and Mitchell2016), while another study defined old age as being age 75 years and older (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Sheehan and Ferris2002). Official retirement age, and age-defined eligibility for pensions and old age supports, likely make different age cutoffs more relevant depending upon the national context. However, very few studies offered any justification or explanation for their particular definition of “old”. The qualitative studies in the current collection included between eight to 46 study participants, and used different approaches to addressing research inquiries, including grounded theory, naturalistic inquiry, phenomenological approaches, and interpretivist approaches.

About a third of the studies made theoretical references or offered unique conceptual or theorization to this area of inquiry. The studies that centrally featured a theoretical or conceptualization of food insecurity, whether uniquely presented in that study or drawn from previous literature, were summarized according to their conceptual contribution to this area of research.

Thematic Analysis

Although many studies did not offer a theoretical framework, some outlined conceptual mechanisms. These mechanisms that were implicitly or explicitly used to explain the relevance of food insecurity and aging are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Thematic representation of conceptual mechanisms hypothesized to connect aging to food insecurity

Major themes that emerged from these explanatory mechanisms were as follows: aging, life course, geography, living arrangement, social-relational, subgroup disadvantage, gender, race/ethnicity, income, health, disability, chronic illness, and behaviour. For example, with respect to the theme of aging, sub-themes of complexity, aging process, and physical/cognitive/physiological differences were used to conceptually connect aging to food insecurity. Some researchers pointed to the complexities that aging introduces to issues of food insecurity (i.e., co-existence of functional impairments, social isolation, adverse effects of multiple medications, depression, limited access to resources, challenges in local food environment), whereas other researchers placed more emphasis on age as a process that renders increasing vulnerability with time (i.e., increasing reliance on others, with age; the onset of physical, physiological, and social changes that impede the ability to obtain and prepare optimal meals). Other researchers took on yet a more comparative stance with respect to age, where they contrasted vulnerability of food insecurity among older people as compared to younger people (i.e., food insecurity may be less prevalent among older people, but the health consequences may be more serious; dietary vulnerability and malnutrition is of greater concern among older people).

We also found several contradictions between sub-themes within broader themes. For example, with respect to income, fixed income and government concessions and income supports were proposed to be detrimental in some studies and protective in others. Similarly, with respect to the life course for older people, cumulative disadvantage was used to explain age-related vulnerability in some studies, whereas resilience, coping skills, resourcefulness, past experiences, and generational lens were proposed to be protective against food insecurity for older people in others. There was also a subset of mechanisms that were directed towards explaining the potential under-detection of food insecurity among older people, including selectivity bias, phenomenological difference, and reporting bias (Table 4). These mechanisms offer three main explanations as to how food insecurity may artificially appear to be lower among older people as compared to younger populations; namely, that the people being sampled may be biased towards some sort of healthy survivor effect (selectivity bias), or that older people may have different reporting tendencies (reporting bias). The other explanation is that food insecurity is experienced or perceived differently by older people as compared to younger people, and thus is not accurately captured using current survey instruments (phenomenological differences).

Table 4: Mechanistic explanations of potential sources of under-detection of food insecurity among older people

Rationale and implications of each study were also examined (Table 5). Thematic analysis of the rationale from these studies mapped onto ecological levels: individual, interpersonal, and societal (Table 6). The ways that food insecurity among older people was problematized on a societal level mainly involved expenditures and economic consequence, with very few references to social loss framed as social inequality. One theme that threaded through all three levels was food insecurity and aging as it related to health, whereby the emphasis was on the problem of health decline as a burden individually (adverse health outcomes), interpersonally (caregiver burden), and societally (increased health care expenditures). The vast majority of studies were found to cite an “aging population” as the principal justification for this area of inquiry.

Table 5: Summaries of rationale and implications for each study in the current review collection

HRQoL = health-related quality of life; NH = neighbourhood; OAANP = Older Americans Act Nutrition Program; QoL = quality of life; SES = socio-economic status

Table 6: Thematic representation of the ways that food insecurity was problematized among older people (themes included individual, interpersonal, and societal level issues that researchers presented as being related to food insecurity among older people)

Health tended to be the main outcome (problem) of interest, despite not having been included in any health-related search terms. As presented in Figure 2, there were two ways that aging and food insecurity tended to be problematized from closely examining the rationale in these studies: food insecurity as it impacted aging and health, and aging as it impacted food insecurity and health. More specifically, the rationales were presented in such a way that either food insecurity exacerbated age-related declines in health, or aging worsened health-related outcomes deriving from food insecurity. Descriptors of the relationships between food insecurity, aging, and health included buffer, exacerbate, interrelate, contribute, impact, and aggravate.

Figure 2: Conceptual representation of how aging and food insecurity tended to be related to health in the rationale of the current collection of studies

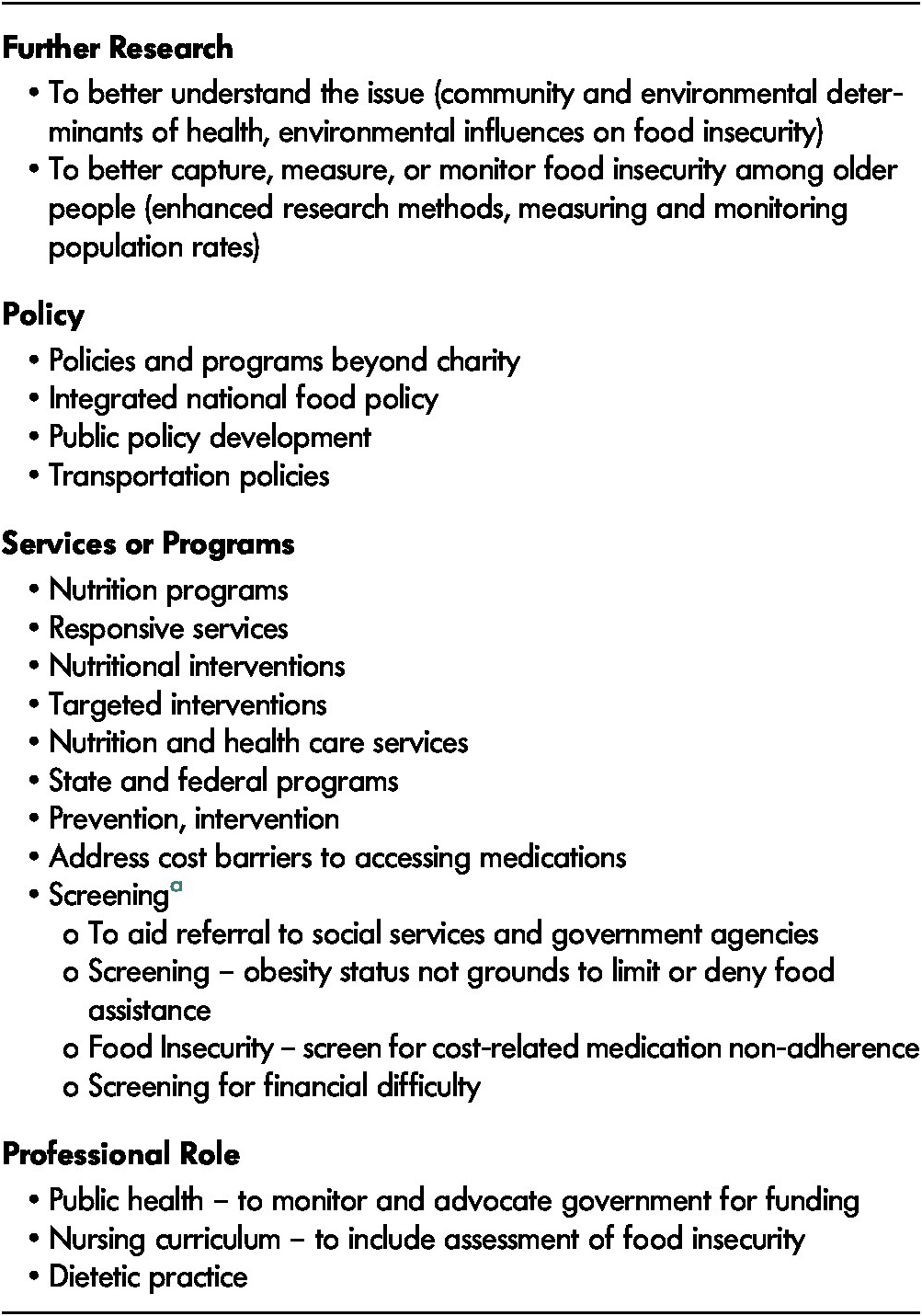

Thematic analysis of the implications from these studies, in terms of how researchers framed their findings, and how and where study findings were directed, included (a) to prompt or support further research; (b) to set policy; (c) to guide the content, target, or evaluate services or programs (including screening); and (d) to suggest a professional role in addressing food insecurity among older people (Table 7).

Table 7: Thematic representation of how and where study findings were directed (themes included research, policy, services/programs, and professional uptake)

a Screening was considered to be a sub-category of services and programs, as all of the screening implications were written in the context of services or programs.

Discussion

We undertook this literature review to bring together the disparate literature concerning food insecurity among older people, with the goals of clarifying some of the tendencies and contradictions of this broader literature, as well as prompting more critical examination of the ways that aging is relevant to food insecurity research.

Our research objectives were to (a) characterize the methodological, empirical, and conceptual contributions of each study; and to (b) thematically analyse the rationale and implications underpinning each study, as well as those conceptual mechanisms hypothesized to connect aging to food insecurity. Studies arose from a variety of research traditions, as well as a mix of methodological approaches. We found age and food insecurity to be operationalized very differently across studies. These differences likely derived from the multi-disciplinarity of this area of inquiry, as well as the widespread use of already existing data sets. Methodological differences were also likely attributable to the stated concerns around the uniqueness of the phenomenon of food insecurity among older people and, accordingly, a perceived potential inadequacy of food insecurity survey instruments to fully capture the complexity and extent of the issue in the older population.

Estimates of food insecurity among older people varied greatly between studies, which was likely caused by different research contexts, as well as different measurement instruments used between studies. These findings underscore the critical importance of consistent measurement, particularly the employment of the HFSSM which has been shown to be an appropriate measure of food insecurity among older people (Nord, Reference Nord2003). Our findings also underscore the value of national population-level monitoring, as there currently exist few studies which would allow for international profiling of this issue for comparison purposes. Overall, with few exceptions, there was little exploration of ecological levels of influence on food insecurity beyond the individual, to include geographical, political, or social influences. For example, while many studies statistically controlled for income, or other measures of socio-economic status, only one study questioned the economic circumstances as the basis of the research (Emery, Fleisch, & McIntyre, Reference Emery, Fleisch and McIntyre2013b).

Empirically, the emphasis of this collection of studies tended to attempt to explicate the perceived “complexity” of food insecurity among older people according to a range of different risk factors or predictors of food insecurity. This collection of studies tended to be pre-occupied with individual risk factors for food insecurity, and individuals’ experiences of food insecurity. Health was prominently featured in this collection of studies, as either the outcome of interest or as mediating or moderating risk factors for food insecurity, or the lens through which older people experienced food insecurity. For example, a small collection of studies found evidence of trade-off behaviours specific to older people, including medication underuse (Afulani, Herman, Coleman-Jensen, & Harrison, Reference Afulani, Herman, Coleman-Jensen and Harrison2015; Bengle et al., Reference Bengle, Sinnett, Johnson, Johnson, Brown and Lee J2010; Bhargava et al., Reference Bhargava, Lee, Jain, Johnson and Brown2012; Sattler & Lee, Reference Sattler and Lee2013), and household utilities usage (Nord & Kantor, Reference Nord and Kantor2006), or “treat or eat” and “heat or eat” trade-offs respectively.

In characterizing the conceptual contributions of this area of research, we detected conceptual ambiguity with respect to the relevance of aging to food insecurity. This was evidenced in two ways; first through the limited application of theory, and second, through the many assumptions that we found to be taking place as determined by mining the mechanisms implicitly proposed by researchers to connect food insecurity to aging.

In documenting all of the theoretical references, applications of theory, and novel conceptual models and frameworks, we found that much of the theorization in this collection of studies to be oriented towards explaining how older people uniquely experience food insecurity and are uniquely vulnerable to food insecurity. For example, many theoretical applications delved into the ways that different ecological factors influence food access for older people (Goldberg & Mawn, Reference Goldberg and Mawn2014; Keller et al., Reference Keller, Dwyer, Senson, Edwards and Edward2006; Wolfe, Olson, Kendall, & Frongillo, Reference Wolfe, Olson, Kendall and Frongillo1996). Of the researchers that constructed their own conceptual models, we found the models to predominantly situate food insecurity in a pathway of interrelationships with other health behaviour risk factors and outcomes, which could be described as frameworks of disease and disability processes (Brewer et al., Reference Brewer, Catlett, Porter, Lee and Hausman2010; Klesges et al., Reference Klesges, Pahor, Shorr, Wan, Williamson and Guralnik2001; Sharkey, Reference Sharkey2004). A collection of studies by Wolfe et al. (Reference Wolfe, Olson, Kendall and Frongillo1996, Reference Wolfe, Olson, Kendall and Frongillo1998, Reference Wolfe, Frongillo and Valois2003) sought to demonstrate how food insecurity is complicated among older people. Specifically, these researchers comprehensively related a diversity of factors that contribute to and reinforce food insecurity among older people (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Olson, Kendall and Frongillo1996), outlined the time-framed progression of food insecurity (Wolfe, Olson, Kendall, & Frongillo, Reference Wolfe, Olson, Kendall and Frongillo1998), and characterized the different components of the experience of food insecurity (Wolfe, Frongillo, & Valois, Reference Wolfe, Frongillo and Valois2003).

Many studies did not make any theoretical references. Without an explicit theoretical framework to guide the research inquiry, study findings and implications are more apt to take on and reinforce status quo assumptions around aging and the root causes of food insecurity (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Kristjansson, Harris, Armstrong, Cummins, Black and Lawrence2010). By thematically analysing the hypothetical mechanisms that were most often passively offered and not substantiated with evidence or a citation, we found that many assumptions were being made as to how aging relates to food insecurity. In doing so, we drew on concepts from the “sociology of knowledge”, such that the production of knowledge must be contextualized within the historical and social space in which it is produced. Scientific knowledge is socially produced and reproduced, and is not inherently unbiased, objective, or politically neutral as it is often presented. Such unchallenged “knowledge” can act as a normalizing force by coordinating social practices and influencing popular perception, and is aptly represented in research endeavors. We were able to demonstrate some clear tendencies with respect to the ways that researchers have assumed aging to be relevant to food insecurity.

One of the major themes of our analyses was “complexity” in that aging is complicated and introduces a whole host of changing variables – particularly physical decline – that coincide with inadequate income, making it difficult to accurately measure and/or address the issue of food insecurity among older people. The portrayal of food insecurity among older people as being complicated by their presumed frailty and dependence runs aground as it relies on the notion of universality of risk as well as purports false equivalency with respect to the importance of risk factors. Complexity also suggests the impossibility of capturing – let alone addressing – the issue, and the futility in approaching the issue with a single intervention lever. Another major assumption was with respect to the “aging process”, whereby aging was framed as progression entailing inevitable (and often insinuated universal) general decline, disability, and disease. Although there are indisputably physical, physiological, and social changes that take place as people get older, the assumption that a group of people above a certain age, or even those who share the same chronological age, are all self-resembling is not scientifically substantiated. Such assumptions equating old age with illness and requiring expensive medical intervention are increasingly being questioned. On the contrary, there is evidence to suggest that older people are experiencing improved (health adjusted) life expectancy (Cutler, Ghosh, & Landrum, Reference Cutler, Ghosh, Landrum and Wise2014; Steensma, Loukine, & Choi, Reference Steensma, Loukine and Choi2017).

Other evidence of normative assumptions on aging were found in the ways that food insecurity was problematized in the stated study rationales. Many studies were based on the premise of projected demographic changes, resulting in increased numbers of older people consuming nutritionally inadequate diets (for whatever reason), ultimately resulting in increased and unsustainable health care expenditures. Such assumptions about morbidity and disability, and what the aging population will mean for health care and social spending, is consistent with the social construction of aging as a medical problem. What has been described as contemporary demographic alarmism is based on the notion that the increase in proportion of older people in a population is a burden, as older people are cast as a drain on society’s resources. Indeed, many scholars suggest that continuously emphasizing the “frail and malnourished senior” alongside the looming health care crises is a form of ageism that functions to provide legitimacy for moves to limit existing social provision for the older population.

Our thematic analysis of the ways that researchers suggested their studies would contribute to addressing this issue included; further research, policy, services, and programs – including screening, as well as defining professional roles. These implications are also consistent with the way that Estes and Binney (Reference Estes and Binney1989) had the foresight more than three decades ago to observe thepower of the biomedical paradigm to “both define the phenomena of aging in biomedical terms, and to pursue policy makers that the solutions to the aging problem are ones that perpetuate control by biomedicine” (p 589). They described four dimensions of the “praxis of aging as a medical problem” – to include the scientific, the professional, and the policy area, and the lay or public perception; and discuss how these dimensions and their consequences contribute to the unbridled dominance of this model (p. 587). For example, the scientific dimension of the praxis Estes and Binney (Reference Estes and Binney1989) describes old age as a “process of basic, inevitable, relatively immutable biological phenomena” which “fosters research on the isolation, etiology, and intervention of these processes … contributing to a trend of methodological individualism and reductionism” (p. 588)… whereby solutions to aging issues are “contingent upon the continuation of biomedical research” (p. 589). Other literature on food insecurity has demonstrated how such an individualized and de-politicized research focus is inadequate to address this issue across all ages (Carlson, Reference Carlson2014; Poppendieck, Reference Poppendieck, Maurer and Sobal1995; Riches, Reference Riches1999).

It is important to differentiate between social security programs and social and welfare services. For example, in Canada, social security programs are the responsibility of federal, provincial, and territorial governments to provide direct economic assistance including Old Age pensions and other social assistance programs. Social and welfare service programs, on the other hand, are community-based and developed to respond to individual needs entailing services such as home-delivered meals. Emphasizing the introduction or revision of food-based services and programs, as many studies in the current collection do, inadvertently reinforces the role of community and food-based interventions, and is contrary to a rich and established literature which points to the ineffectiveness of food-based solutions to food insecurity (Tarasuk & Davis, Reference Tarasuk and Davis1996; Power, Little, & Collins, Reference Power, Little and Collins2015; Rideout, Riches, Ostry, Buckingham, & MacRae Reference Rideout, Riches, Ostry, Buckingham and MacRae2007).

A handful of studies also pointed to the role of health professionals to incorporate screening or awareness of food insecurity among older people as part of professional training and practice. Estes and Binney (Reference Estes and Binney1989) discussed how the biomedical model leverages professional activities to self-reinforce the process of biomedicalization of an issue that might have once fallen outside the purview of biomedical-clinical practice.

Taken as a whole, the thematic analyses from the current collection of studies all suggest that there is a strong tendency towards biomedicalization in this literature overall. These tendencies include a heavy emphasis on the aging population, the health and social burdening of older people with food insecurity, the gerontological complexity of this issue relating to non-income factors, and de facto inevitability and homogeneity of aging processes, with an emphasis on individualized and de-politicized solutions to this issue.

To our knowledge, this is the first “literature review” to specifically focus on food insecurity and aging. Although other reports and literature reviews on food insecurity have included studies that include older age groups in the analysis (Gundersen & Ziliak, Reference Gundersen and Ziliak2018), this work does not contribute to the same extent to the knowledge base of how aging is relevant to food insecurity research.

Limitations of the current study are mainly those that affect what studies were included or excluded, and thus the major limitation is that the conclusions of this study are provisional. For example, our search strategy was explorative and generative, based on key search terms that were subsequently narrowed. We sought to select the most appropriate set of databases and define the most relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria. We included only studies that were published in English for pragmatic reasons. We did not search the grey literature because the emphasis of our research question focused on the state of the academic literature.

One such collection of grey literature that is of relevance to the issue of food insecurity among older people, but was not included in the current review, is the series of annual research reports on the state of senior hunger in America (Ziliak, Gundersen, & Haist, Reference Ziliak, Gundersen and Haist2008; Ziliak & Gundersen, Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2009, Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2011, Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2012, Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2013a, Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2014, Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2015, Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2016, Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2017). These reports, which have been undertaken since 2008, draw upon data from the Current Population Survey and offer detailed estimates and risk profiles of food insecurity among older Americans over time, and also outline causes and consequences of food insecurity among older people (Gundersen & Ziliak, Reference Gundersen and Ziliak2017; Ziliak, Gundersen, & Haist, Reference Ziliak, Gundersen and Haist2008; Ziliak & Gundersen Reference Ziliak and Gundersen2013b). We mention these reports here but elected not to include them in our review, as they indeed form part of the literature on this issue, but more so as a separate entity of their own. The different reports vary considerably in format, length, and style, which does not render them easily comparable with the peer-review literature that we did include. However, this collection of reports could be examined from the same angles as has been done in the current review: for example, noting theoretical references, identifying hypothetical mechanisms that connect age to food insecurity, and in turn, discerning normative assumptions that may contribute to the biomedicalization of this issue.

The current review did not focus on reports or studies that examined food insecurity across all ages, but rather focused on studies that specifically featured older people. This inclusion criterion was decided upon because we sought to examine how researchers approached age with respect to food insecurity versus describe the problem of food insecurity in different age categories. We determined that studies that included all ages would be much less likely to delve into the ways that aging relates to food insecurity.

Limitations with respect to the thematic analysis we conducted would include the same issues of rigor and transparency that other qualitative studies face, in that this process is subjective despite the involvement of multiple reviewers. It is possible that other researchers would offer different sets of insights from this same collection of literature. Consistent with the established methodologies for undertaking a scoping study and in contrast with systematic review methodologies, we did not appraise the quality of studies that were included. Rather, we necessarily included all studies that met our search criteria, as we sought to comment more broadly on the state of research on this issue. Future directions for this research are plentiful – but primarily it will be important for people in this area of research to advocate for improved population-level monitoring of food insecurity using standardized survey instruments. The current smattering of ways that food insecurity and older people are operationalized has resulted in an overall collection of literature with limited empirical comparability. Such methodological comparability is essential for international comparisons, and would better allow for researchers to expand the scope of their research from the more microcosmic milieu of risk factors to considering broader cultural, social, and political contexts.

Furthermore, it will be imperative to interrogate the issue of food insecurity among older people as an economic issue, using increasingly sophisticated economic indicators. As food insecurity is better defined as a state as opposed to an outcome, linking different population data sets, and collecting longitudinal data may prove to hold tremendous potential in this regard. Indeed, the absence of comprehensive existing data, and longitudinal data in particular, in many ways limits the ways that food insecurity among older people is examined to static, individual-level parameters.

Moreover, this research could be better served by the application of critical social theories (Estes, Biggs, & Phillipson, Reference Estes, Biggs and Phillipson2003). Without engaging with food insecurity and aging more critically, this research will continue to be rooted in biomedicalized, individualized, and de-politicized understandings of why food insecurity is important, and in what ways aging is relevant to its study. Moving forward it will be important for researchers in this area to make explicit their ideological position with respect to food insecurity and aging (Bengtson & Settersten, Reference Bengtson, Settersten, Bengston and Settersten2016). For example, our study demonstrates how some research purports universalism with respect to nutritional challenges among older people, in that all older people are at risk of nutritional deficiency just by the fact of being old, and that all older people are vulnerable to food insecurity accordingly. Other research implies that the injustice of food insecurity lies in the differential vulnerability among sub-groups of older people, enacted through inequalities in health-related behaviours and endogenous risk factors for food insecurity. Other research yet focuses on differential access to food assistance, among older people, and compared to younger people.

Few researchers are examining economic inequalities within and among older people. Researchers might clarify whether they view food insecurity among older people as a condition, a health outcome, a predictor of other health outcomes (and expenditures), a proxy or indicator of deprivation, or an injustice in and of itself. To question the acceptability or inevitability of any level of food insecurity in a population or sub-population, and accordingly the social and political root causes, is reflected in discourse and can be mapped onto research and practice paradigms and the practical implications ascribed therein (Raphael, Reference Raphael2011).

And lastly, this review did not include a chronological component, where studies were assessed unilaterally rather than by publication date. This decision was made early on in the study selection process, as studies were arising from different fields, different countries, and at different points in time. We surmised that disentangling a timeline of publication importance and influence was secondary to our stated objectives. However, as this area of research continues to evolve, it will be important to begin to better understand how disciplinary biases and socio-political, contextual factors have shaped the established research agendas in this field to date.

Conclusion

Overall, in this scoping study we were able to bring together a diverse literature on food insecurity and aging. Several important findings emerged from characterizing our collection of studies methodologically, empirically, and conceptually. Taken together, we found that this literature is missing out on conceptual clarity and a cohesive direction, and this was reflected in the different operationalizations of food insecurity and age, the sparse application of theory, and the thematic analysis of study premise and purpose which demonstrated strong implicit tendencies towards biomedicalization of this issue. We found that this literature could benefit from more deliberate application of concepts and theories from aging scholarship. As discussed, the ways that research is framed and directed has tremendously important bearing on the ways this issue is targeted in future policies and practice.

Sources of Funding:

Mark Rosenberg is the Tier I Canada Research Chair in Development Studies. This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program.

Ethics:

This review did not require ethics approval.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions:

MR and JL conceptualized the review topic, and a general search strategy. JL and JC conducted the literature review. JL drafted the paper, and MR provided direction and advice during the drafting of the paper, as well as feedback and edits on various drafts. All authors read and approved the final submission of the paper.