There is concern about cannabis use, particularly among teenagers, and about its potential effect on the health, achievement and behaviour of young people (Reference JohnsJohns, 2001). Cannabis use appears to have become more frequent among the young (Reference Hall, Johnston, Donnelly, Kalant, Corrigall and HallHall et al, 1999) and cannabinoid content has increased dramatically in the past 20 years (Reference AshtonAshton, 2001). Adolescence is the developmental stage when drug-using patterns emerge and teenagers may be more vulnerable than adults to the effects of cannabis (Reference Chen, Kandel and DaviesChen et al, 1997). A national survey recently completed in Australia (Reference Sawyer, Arney and BaghurstSawyer et al, 2000a ) provides data that can be used to expand knowledge in this field. The aims of this study were to ascertain: the prevalence of cannabis use among Australian adolescents; the demographic characteristics of adolescents who used cannabis; whether there were associations between cannabis use, mental health problems and health risk behaviours; and how often adolescents who used cannabis accessed health services.

METHOD

Design

The study used data from a representative sample of 1490 adolescents aged 13-17 years who participated in the child and adolescent component of the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing conducted in Australia in 1998 (Reference Sawyer, Arney and BaghurstSawyer et al 2000a ). Ethics approval was given by the Research Ethics Committee at the Women's and Children's Hospital, Adelaide. The survey method has been described elsewhere in detail (Reference Sawyer, Kosky and GraetzSawyer et al, 2000b ). In summary, multi-stage probability sampling of households with children younger than 18 years was used to obtain a representative sample of 4509 Australians aged 4-17 years. Clusters of 10 households with children in the required age range were sampled from each of 450 Census Collector's Districts across Australia. The number of Census Collector's Districts sampled were in proportion to the size of the target populations within each region and were distributed proportionately across metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. There were no differences in the demographic characteristics of children, parents and families who participated and those of the population from which they were selected (based on the 1996 Australian Census), with the exception of age. Children aged 4-5 years were slightly over-sampled whereas those aged 16-17 years were slightly undersampled.

Instruments

Adolescents completed the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Reference AchenbachAchenbach, 1991a ), the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ; Reference Landgraf, Abetz and WareLandgrafet al, 1996), a self-rating depression scale (the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale; Reference RadloffRadloff, 1977) and the Youth Risk Behaviour Questionnaire (YRBQ; Reference Brener, Collins and WarrenBreneret al, 1995). Adolescents placed completed questionnaires in a sealed envelope to ensure confidentiality.

Parents or main caregivers (henceforth described as ‘parents’) were interviewed using the parent version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV (DISC-IV; Reference Shaffer, Fisher and LucasShafferet al, 2000). Parents also completed the parent version of the CHQ (Reference Landgraf, Abetz and WareLandgraf et al, 1996), the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; Reference AchenbachAchenbach, 1991b ) and an interviewer-administered questionnaire covering demographic and service use information.

Measures

The YRBQ completed by adolescents was employed to determine cannabis use and other health risk behaviours. The YRBQ has four questions about cannabis (marijuana) use: “how old were you when you tried marijuana for the first time?” (categorised as never, ≤12 and ≥13 years of age); “ During your life, how many times have you used marijuana?” (0, 1-2, 3-9, 10-19, 20-39, 40-99, >99 times); “During the past 30 days, how many times did you use marijuana?” (0, 1-2, 3-9, 10-19, 20-39, > 39 times); and “During the past 30 days, how many times did you use marijuana on school property?” (0, 1-2, 3-9, 10-19, 20-39, >39 times). Other health risk behaviours considered were suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts during the past year, cigarette smoking (≥10 cigarettes during the previous month), alcohol use (≥5 drinks at least once in the previous month) and use of other drugs (having ever used any other non-prescribed drug of abuse or inhalants).

Ratings of emotional and behavioural problems according to parents and adolescents were obtained using the CBCL and YSR scales, respectively. The Delinquent Scale of the CBCL and YSR contains one item (no. 105) on substance use. To avoid spurious associations, scores on this scale were computed without item 105. Ratings of depression were obtained from the adolescent using the CES-D.

Diagnoses of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder were obtained using the DISC-IV administered to parents. Prevalence of ADHD in adolescents was 7.1% and of conduct disorder was 2.4%.

Depression was considered to be present if either parent or adolescent reported significant depression. A detailed description of the method used is available in Rey et al (Reference Rey, Sawyer and Clark2001). In summary, for parents' reports it required meeting the criteria for DSM-IV major depression or dysthymia (DISC-IV interview). For adolescents, this was defined as having clinically significant depression during the previous week (CES-D >20 for males and >22 for females; Reference Roberts, Lewinsohn and SeelyRobertset al, 1991) and significant impairment in psychosocial functioning (past 4 weeks) as measured on the CHQ. According to this, 8.2% of participants met the criteria for depression. Demographic and service use data were obtained from parents' interviews.

Statistical analysis

Variables rating demographic characteristics, service use and risk behaviours were dichotomous or dichotomised for analysis and were examined using χ2 and odds ratios. Alpha was set at 0.05. Reported percentages are rounded to the nearest unit.

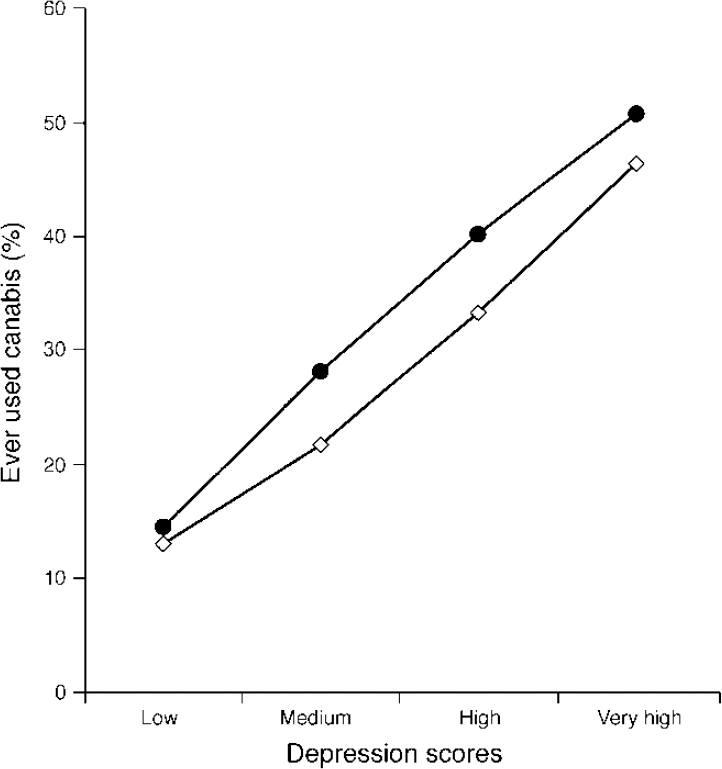

Figure 1 shows depression scores as reported by adolescents (CES-D) according to their severity as low (bottom 50%), medium (next 25%), high (next 15%) and very high (top 10%), computed separately for boys and girls.

Fig. 1 Rates (%) of adolescents (□, male; [UNK], female) who had ever used cannabis, according to depression scores on the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale.

There were significant associations between many of the independent variables (e.g. between YSR scales). To control for this, the variables that were different between the groups in univariate analyses in Tables 2 and 3 were entered into logistic regression models. Cannabis use (no=0, yes=1) was the dependent variable. When both CES-D scores and scores on the anxious/depressed scale according to the adolescent were different between groups, only CES-D scores were included in the appropriate multivariate analyses. Owing to the large effect of age on cannabis use, age was included in all multivariate analysis.

Table 1 Adolescents who ever used cannabis, by age and gender

| Age | Males | Females | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 9/121 | (7%) | 9/128 | (7%) | 18/249 | (7%) |

| 14 | 22/145 | (15%) | 36/156 | (23%) | 58/301 | (19%) |

| 15 | 32/127 | (25%) | 36/141 | (26%) | 68/268 | (25%) |

| 16 | 51/134 | (38%) | 58/149 | (39%) | 109/283 | (39%) |

| 17 | 33/72 | (46%) | 33/88 | (38%) | 66/160 | (41%) |

| Total | 147/599 | (25%) | 172/662 | (26%) | 319/1261 | (25%) |

Table 2 Behavioural and emotional problems (mean scores) according to cannabis use in the past month

| Measure | Not at all | Once or twice | Three or more times |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent (CBCL) | |||

| Total problems*** | 16.2 | 21.6 | 23.9 |

| Externalising*** | 5.6 | 7.9 | 10.9 |

| Internalising | 5.2 | 6.7 | 5.9 |

| Narrow-band syndromes | |||

| Anxious/depressed | 2.0 | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| Somatic complaints | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Social problems | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| Withdrawn | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Thought problems | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Attention problems** | 2.0 | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| Aggressive | 7.4 | 10.9 | 12.1 |

| Delinquent*** 1 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 3.7 |

| Youth (YSR) | |||

| Total problems*** | 33.6 | 50.8 | 54.4 |

| Externalising*** | 10.3 | 17.2 | 19.7 |

| Internalising*** | 10.4 | 15.0 | 15.1 |

| Narrow-band syndromes | |||

| Anxious/depressed*** | 4.9 | 7.8 | 7.4 |

| Somatic complaints*** | 2.9 | 3.9 | 4.1 |

| Social problems | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| Withdrawn*** | 2.8 | 4.1 | 4.3 |

| Thought problems*** | 1.5 | 2.2 | 2.7 |

| Attention problems*** | 4.1 | 6.4 | 6.5 |

| Aggressive*** | 7.4 | 10.9 | 12.1 |

| Delinquent*** | 2.7 | 5.3 | 6.3 |

| Depression (CES—D)*** | 9.6 | 17.6 | 16.3 |

Table 3 Association between cannabis use and demographic items, risk behaviours, comorbidity and use of services according to univariate (fourth column) and multivariate (fifth column) analysis

| Never (n=942)1 | At least once (n=319)1 | Odds ratio for at least once (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio2(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 52% | 54% | 1.08(0.83-1.39) | — |

| Family type | ||||

| Original (two-parent) | 77% | 64% | 0.53(0.40-0.70) | — |

| Step | 9% | 12% | 1.04(0.94-2.13) | — |

| Sole parent3 | 13% | 22% | 1.94(1.40-2.68) | 1.63(1.07-2.49) |

| Employment | ||||

| At least one full-time | 59% | 60% | 1.05(0.80-1.38) | — |

| At least one part-time | 23% | 19% | 0.80(0.57-1.12) | — |

| Unemployed | 16% | 17% | 1.10(0.77-1.42) | — |

| Income <AU$680 per week | 38% | 40% | 1.06(0.79-1.42) | — |

| Age parent left school | ||||

| Father < 16 years | 35% | 29% | 0.75(0.54-1.03) | — |

| Mother < 16 years | 35% | 37% | 1.08(0.82-1.43) | — |

| Health risk behaviours | ||||

| Planned suicide (past year)3 | 6% | 15% | 2.67(1.78-3.98) | 1.13(0.61-2.11) |

| One or more suicide attempts (past year)3 | 2% | 10% | 4.52(2.58-7.94) | 1.09(0.46-2.62) |

| Smoked cigarettes ≥ 10 days in past month3 | 3% | 39% | 18.64(12.21-28.44) | 7.79(4.75-12.78) |

| Five or more drinks at least once in past month3 | 9% | 48% | 9.62(7.03-13.19) | 4.76(3.26-6.95) |

| Ever used other drugs3 | 12% | 39% | 4.90(3.62-6.63) | 2.78(1.86-4.15) |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Any ADHD | 6% | 7% | 1.22(0.73-2.02) | — |

| Inattentive type | 4% | 4% | 1.04(0.53-2.03) | — |

| Hyperactive type | 1% | 1% | 2.28(0.28-18.49) | — |

| Combined type | 2% | 2% | 1.22(0.50-2.97) | — |

| Conduct disorder3 | 1% | 4% | 3.62(1.61-8.17) | 0.81(0.27-2.44) |

| Depressive disorder3 | 6% | 16% | 3.14(2.10-4.69) | 1.89(1.07-3.34) |

| Service use | ||||

| Any service | 7% | 10% | 1.53(0.98-2.39) | — |

| General practitioner or paediatrician | 2% | 4% | 1.83(0.93-3.61) | — |

| Counselling at school or special class3 | 5% | 7% | 1.67(0.98-2.81) | — |

| Any mental health service | 3% | 4% | 1.29(0.66-2.51) | — |

| Any psychotropic medication | 2% | 1% | 0.59(0.17-2.04) | — |

Missing data

Overall, 229 adolescents (15%) did not answer questions about cannabis use and so were not included in any of the analyses. The sample studied therefore comprised 1261 (85%) of the 1490 participants. A further 101 adolescents (7%) had missing data on at least one relevant variable; they were not included in analyses when the missing variable was considered. Participants with any missing data (n=330, 22%) were no different from those without missing data in age, family income and diagnosis of depression or ADHD. However, participants with missing data were less likely to live in an original two-parent family (68% v. 74%; χ2=5.8,P=0.02) and more likely to be male (56% v. 47%; χ 2=6.9, P<0.01), to have a diagnosis of conduct disorder (4% v. 2%; χ2=6.2, P<0.05), and to have been rated by parents as more disturbed overall in the CBCL (mean total problems=20.8 v. 16.7; t=2.5, P<0.05). This suggests that adolescents whose results were employed in these analyses are less disturbed than adolescents whose results were not included.

RESULTS

Cannabis use

Prevalence according to age and gender is presented in Table 1. One-quarter of the 13— to 17-year-olds in this sample reported having used cannabis, 186 (15%) had used it fewer than 10 times and 136 (11%) had used it 10 times or more. A small minority (n=42, 3%) reported having used it 100 times or more. However, there were no differences according to gender.

Of those who used cannabis, 19% used it for the first time at 12 years of age or younger. Males were twice as likely as females to have used cannabis before the age of 13 years (95% CI 1.2-3.8). Cannabis use increased rapidly with age, on average 1.6-fold per year (95% CI 1.49-1.83). Of those who had used cannabis 42% had used it during the previous month. Few (n=20, 6%) had used the drug at school in the previous month.

Emotional and behavioural problems

The mean raw scores on the various CBCL (parent) and YSR (youth) scales and on the CES-D were compared according to cannabis use in the past month (not at all, once or twice, three or more times). These data are presented in Table 2. Those who used cannabis had more emotional (internalising) and behavioural (externalising) problems than those who did not. Differences were more marked and widespread for youth self-reports than for parents' reports but were consistent for both.

Multivariate analysis (including age, CES-D scores and the narrow-band syndromes that were significantly different in Table 2 as predictors) showed that cannabis use was associated with greater depression (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.03, 95% CI 1.01-1.05), greater delinquent problems (adjusted OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.51-1.82) and lower ‘withdrawn’ scores (adjusted OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81-0.98) according to adolescents and with lower attention problem scores according to parents (adjusted OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.86-0.99) (model χ 2=364.36, d.f.=10, P<0.001). These odds ratios refer to an increase of one scale point.

Figure 1 shows a gradual increase in cannabis use with increasing self-reported depression scores (CES-D) (males: χ2=46.9, d.f.=3, P<0.001; females: χ 2=52.1, d.f.=3, P<0.001). This association decreases only slightly after controlling for the effect of age on cannabis use from OR 1.62 to adjusted OR 1.60 (95% CI 1.40-1.82) for males and OR 1.68 to adjusted OR 1.65 (95% CI 1.44-1.89) for females. That is, females with depression scores in the top 10% (scores >26 on the CES-D) are five times more likely to have used cannabis than females with scores in the bottom 50% (scores <9).

Demography, diagnosis, risk behaviours and use of services

These data are presented in Table 3. Those who had ever used cannabis were less likely to live in an original, two-parent family and more likely to live with a solo parent. However, use was not associated with other socio-economic variables such as parental employment, education or family income.

Depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder were the only diagnoses considered in the survey. Adolescents who qualified for a diagnosis of depression or conduct disorder were more likely to have used cannabis than those who did not. For example, among the teenagers who had used cannabis, 14% of the males qualified for a depressive disorder compared with 6% of those who had not used it (χ2=9.6,P<0.01). The parallel figures for females were 18% and 6% (χ2=24.9, P<0.001). There was no association with ADHD.

Adolescents who reported having used cannabis were much more likely to report drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes and to have tried other drugs. However, they did not use services more often.

A multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify the relationship between each independent variable and cannabis use, controlling for the effect of the other independent variables in the model (Table 3). In this analysis, living with a sole parent, cigarette smoking, drinking alcohol, using other drugs and a diagnosis of depression were associated with cannabis use (fourth column, Table 3).

DISCUSSION

One-quarter of this sample of 13— to 17-year-olds had tried cannabis at least once. A 1996 survey of 29 447 Australian school-children reported that 36% of 12— to 17— year-olds had used cannabis (Reference Lynskey, White and HillLynskey et al, 1999). In the USA, a 1999 survey showed that 22% of year 8 (13-14 years of age) students and 41% of year 10 (15-16 years of age) students had used cannabis (Reference Johnston, O'Malley and BachmanJohnston et al, 2000). Comparable rates also have been reported in other countries (Reference Hall, Johnston, Donnelly, Kalant, Corrigall and HallHall et al, 1999; Reference Fergusson and HorwoodFergusson & Horwood, 2000).

It could be argued that using the house-hold as the contact point may have inhibited adolescents' answers and that these results underestimate cannabis use. Although all care was taken to protect confidentiality (adolescents were instructed to place completed questionnaires in a sealed envelope), some underestimation is likely given that 15% did not answer questions about cannabis use and that participants with missing data were rated by parents as more disturbed overall. Nevertheless, estimates of use of alcohol and cigarettes in this study were comparable with those reported in other Australian surveys, although the age groups and period considered varied slightly. For example, a national survey conducted in 1998 found that 7.2% of females who had never used cannabis reported having had five or more drinks at least once in the previous 2 weeks (Reference Reid, Lynskey and CopelandReidet al, 2000), compared with 8.2% who had had five or more drinks at least once in the previous month in the present study. In the Australian state of New South Wales, among secondary school students aged 12-17 years in 1996, 19% of boys and 21% of girls reported having smoked cigarettes during the previous week (Reference Schofield, Lovelace and McKenzieSchofield et al, 1998) whereas 45% of each gender reported having ever smoked in the present survey.

Age and gender

There is a strong age effect in the prevalence of cannabis use, with self-reported lifetime use increasing from 7% among 13-year-olds to 41% among 17-year-olds. This is consistent with the results of previous studies (Reference Johnston, O'Malley and BachmanJohnston et al, 2000) and confirms that adolescence is the peak age for cannabis initiation (Reference Chen and KandelChen & Kandel, 1995). Given that age of first use may be an important factor in determining progression to heavy or problematic use (Reference DeWit, Hance and OffordDeWit et al, 2000), such findings raise concerns about the extent to which current levels of use among adolescents may translate into future problematic use. This is particularly worrying because estimates suggest that about one in ten of those who ever used cannabis may develop dependency (Reference Fergusson and HorwoodFergusson & Horwood, 2000; Reference JohnsJohns, 2001). However, most seem to use the drug infrequently: more than 50% used fewer than 10 times and 13% used 100 times or more. This suggests that the high rate of lifetime cannabis use reflects a large amount of experimental and irregular use that does not necessarily progress to regular or heavy use (Reference Reid, Lynskey and CopelandReid et al, 2000).

Prevalence was similar among males (25%) and females (26%). This contrasts with earlier studies reporting strong gender effects, with both the prevalence and frequency of cannabis use being higher among males than females (Reference Hall, Johnston, Donnelly, Kalant, Corrigall and HallHall et al, 1999). These findings confirm recent reports that gender differences in rates of cannabis and other drug use are narrowing as young women increasingly adopt patterns of use that mirror those of their male counterparts (Reference Smith, Rutter, Rutter and SmithSmith & Rutter, 1995; Reference Perkonigg, Lieb and HoflerPerkonigg et al, 1999; Reference Reid, Lynskey and CopelandReid et al, 2000). Cannabis use has increased among females at a more rapid pace, resulting in a narrowing of the gender gap. Something similar is occurring with crime and conduct problems (Reference Smith, Rutter, Rutter and SmithSmith & Rutter, 1995). This also may reflect that cannabis use has become more socially acceptable and destigmatised.

Depression

The association between cannabis use and psychosis has received much attention (Reference Hall and DegenhardtHall & Degenhardt, 2000). However, links with emotional problems also are relevant. There are suggestions that depressed individuals are more likely to use cannabis and that consumption of cannabis is associated with an increase in anxiety, depression and suicide attempts (Reference JohnsJohns, 2001). In the current study, an association was found between depression (whether conceptualised as a categorical diagnosis or as depressed mood) and cannabis use. The cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow clarification of what comes first or whether both problems are the result of common aetiological factors. This will require further examination in prospective studies.

Disruptive behaviour

Cannabis use among teenagers is part of a pattern of wider substance use (cigarettes, alcohol, other drugs) and conduct problems.

The lack of association with ADHD contrasts with reports of increased substance use among young people with ADHD (Reference Schubiner, Tzelepis and MilbergerSchubiner et al, 2000; Reference Wilens, Biederman and MickWilens et al, 1997). The results of this survey are consistent with evidence showing that ADHD does not seem to increase the risk of cannabis use, although in this study concurrent ADHD was considered rather than ADHD that clearly preceded drug use. Because substance use is strongly associated with conduct problems, the reported association with ADHD, particularly in clinic samples, may be due to comorbidity between ADHD and problems of conduct (Reference Lynskey and FergussonLynskey & Fergusson, 1995; Reference Chilcoat and BreslauChilcoat & Breslau, 1999; Reference Disney, Elkins and McGueDisney et al, 1999).

The association between cannabis use, depression, conduct problems, tobacco smoking, excessive drinking and use of illicit drugs shows a malignant pattern of comorbidity that may lead ultimately to further negative outcomes. Preventing this will require more than health education about drug issues, and it will need close involvement of child and adolescent mental health services.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

• Given the increasing frequency of cannabis use, practitioners need to enquire about its use, particularly among younger teenagers, to prevent wider and further drug use.

-

• Clinicians should think about the possibility of depression in adolescents who use cannabis.

-

• Clinicians need to ask about cannabis use in depressed adolescents, in those who smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol or who display conduct problems.

LIMITATIONS

-

• Findings are applicable to Australia in 1998 but may not reflect the frequency or correlates of cannabis use in other countries or at other times.

-

• Prevalence of cannabis use may have been underestimated because older adolescents were undersampled and a substantial number did not answer questions about use — and these adolescents were more disturbed.

-

• Owing to the cross-sectional nature of the study, associations do not necessarily reflect causal relationships.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to R. J. Kosky (Chair), B. Nurcombe and S. R. Zubrick, members of the National Collaborating Group, who facilitated the design and implementation of the survey.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.