In this essay, I offer some reflections on how Victorianists might understand nineteenth- and early twentieth-century discursive practices for mapping Africa. In doing this, I respond to what Sukanya Banerjee, our panel organizer, asked us to do in determining the focus for our essays—namely, that we direct “attention to topics in Victorian studies that [we] feel might otherwise be overlooked or viewed differently.” In what follows I introduce and problematize a series of Victorian-era maps or, more specifically, problematize what such maps represent conceptually, then offer some alternate means by which Victorianists might critically engage with cultural and social reality on the nineteenth-century African continent, particularly the more southern and eastern parts of the continent where much of my prior research has focused.

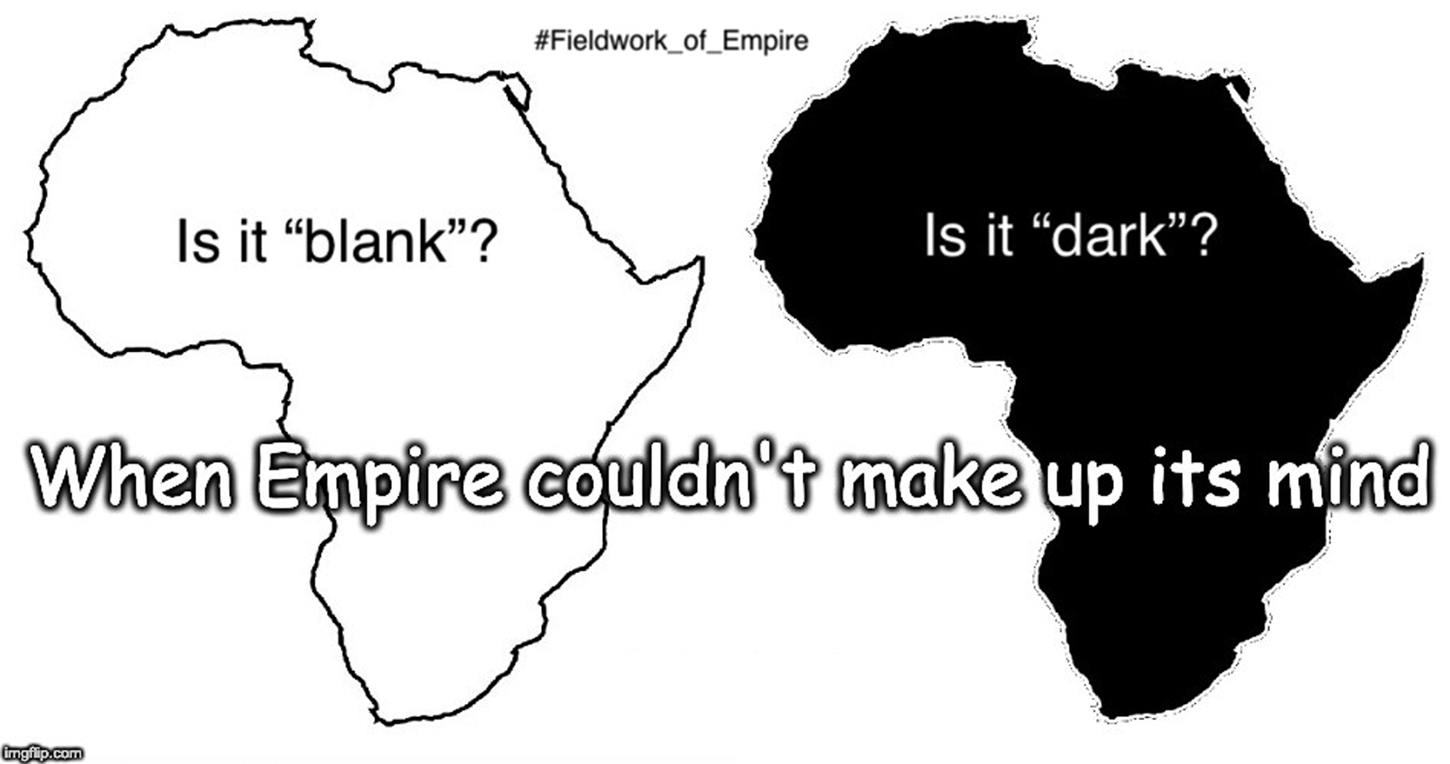

Figure 1, a meme taken from my book Fieldwork of Empire (2019), speaks to common perceptions of how Victorians tended to represent the African continent, that the continent alternates between being “blank” and being “dark” in Victorian imperial discourse. The meme also engages with chronology by nodding to the idea that Africa, during the Victorian era, evolved in such discourse from being the former to being the latter. Other nineteenth-century representations of Africa show that “blank” during the era often meant that cartographers could only include a limited range of geographical features (e.g., Burton et al., inset map). By contrast, later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Victorian maps of the continent represent the continent in a way that reflects the European partition of the continent and shows different European colonial possessions clearly marked by hard borders (e.g., Hertslet et al.; see fig. 2). Collectively, these latter two types of maps—the limited geographical map and the colonial border map—provide actual era-specific instances of the representations to which my meme speaks. The maps also hint at the means by which local cultural and geographical knowledge—the basis of other earlier maps of Africa—came to be replaced by European knowledge in later maps.

Figure 1. Adrian S. Wisnicki, “When Empire Couldn't Make Up Its Mind.” Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki: Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0).

Figure 2. Edward Hertslet et al., “General Map of Africa Shewing Approximately the Territorial Boundaries and Spheres of Influence of the Different European and Other States on the African Continent, 1909.” Public domain.

Key steps in this historical process occurred during the latter half of the nineteenth century, and attention to relevant Victorian-era maps enables scholars to track the change. For instance, the maps produced by Richard Burton and John Speke during their late 1850s East African expedition show how the travelers mapped their own routes and how they instituted their own knowledge on “blank” spaces (fig. 3). In their maps, everything but the direct line of their travels is shown as a blank, though their maps do still make some reference to the fact that the men were following well-established African and Arab trading routes. Other expeditions used their maps to delineate the boundaries of different cultural groups, thereby imposing pseudo-nation-states on the continent (e.g., Grant and Speke) and thus, one might argue, inadvertently laying the groundwork for the later partition of Africa. Yet such maps, despite their potential inventiveness, also elide the messiness of fieldwork—the fact that Victorian explorers worked with local informants and gathered geographical data based on local priorities. Figure 4, a map drafted by David Livingstone in the early 1870s, demonstrates this point by documenting a region he never visited and citing at least one informant, Said bin Habib, an Arab trader, although the map's information may have come from a variety of individuals, African and Arab.

Figure 3. Alexander George Findlay and John Hanning Speke, “East African Expedition. Map of the Routes between Zanzibar and the Great Lakes in Eastern Africa in 1857, 1858 & 1859. by Captns R. F. Burton and J. H. Speke.” Public domain.

Figure 4. David Livingstone et al., “Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863),” excerpt. Copyright National Library of Scotland, Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland); and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant): Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0).

Yet whatever the material reality of fieldwork, Victorians characterized their final products—the maps—as progress, as the creation of knowledge where there had been none. The move, however, ignored the fact that Europeans, with help from local informants, had already been engaged in mapping large parts of Africa earlier, including—in a lot of cases—interior regions never visited by Europeans. Such mapping often drew on oral knowledge gained from local trade and trading routes. Late nineteenth-century mapping practices thus depended on erasing and/or rewriting earlier knowledge. Figure 5, for example, a map that appeared just a few years earlier than those of Burton and Speke (see above), shows a series of trading routes from the East African coast into the interior. The map also embeds longer segments of prose, in situ, to denote other geographical data provided by informants. Such nineteenth-century maps, therefore, offer a window onto how local African and Arab knowledge circulated via trade and so could be collected and assembled by Europeans in the first place.

Figure 5. Jacob Erhardt et al., “Skizze Einer Karte Eines Theils von Ost u. Central Afrika Mit Angabe Der Wahrscheinlichen Lage u. Ausdehnung Des See's von Uniamesi Nebs Bezeichnung Der Crenzen u. Wohnsitze Der Verschiedenen Völker Sowie Der Caravanen Strassen Nach Dem Innern.” Public domain.

Elements of scholarship in African studies since the 1960s have focused on getting back to that early nineteenth-century knowledge of the different regions of the African continent. Some scholars have concentrated on trading routes.Footnote 1 Others have centered their work on the distribution of cultural groups.Footnote 2 Yet others have combined geography with an emphasis on cultural groups plus cultural borders that are not quite closed.Footnote 3 This is not the place to untangle these different strands of work in African studies. Rather I've roughly drawn attention to these trends, while noting that development over time also means going back in time, to earlier ways of knowing the African continent. For Victorianists who want to engage nineteenth-century African knowledges, cultures, and histories, this brief sketch also suggests a few important points for new research.

First, it's important that scholars move away from using imperial frameworks like the nation-state as ways of engaging with cultural, social, and political realities in nineteenth-century Africa. Rather, Victorianists should understand that nineteenth-century African material reality was based on different elements, like spheres of influence and population mobility in relation to trade, conflict, or other factors. Second, it's worth considering precolonial and early-colonial African identity as being relational and fluid, with boundaries not necessarily fixed but rather porous. Indeed, this approach, one that forgoes continental totality and instead conceptualizes regionally or focuses on relationships between diverse, not always easy to distinguish cultural groups, is one that Africanists often favor in the present day.

Finally, in working with nineteenth-century African history, it's crucial to engage a variety of disciplines, such as history (including oral history), anthropology, cartography, and linguistics. Such scholarship, however, should also be critically interrogated. Is one using the work of scholars from the regions under study? If not, do the scholars referenced engage local informants? Is it possible to reach out to individuals in a given region to assist with one's scholarship, for instance, with critical analysis and translation? Are there other contemporary means for recovering history? Can contemporary historical fiction by African and Arab authors (e.g., Gappah, Gurnah) help in illuminating historical contexts? Such concerns also extend to archival sources. My One More Voice project, for instance, takes up the question of Victorian-era “authorship” and suggests that named and unnamed contributors are as important as bylined authors. Colonial archives, the project argues, can be much more diverse and contain many more perspectives than scholars acknowledge—even if we have to be very careful in using mediated sources like those taken up by my project. Ultimately, such sources and multidisciplinary approaches are key to moving beyond totalizing ways of engaging with the nineteenth-century African continent and the many, many people and ethnic groups living across that continent.