As the year 1968 drew to a close, Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu, the president of the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), could take satisfaction from the previous twelve months’ progress. That spring, communist forces had launched an all-out assault on South Vietnam’s cities and provincial capitals, gambling that urban Southerners would join them in toppling Thiệu’s fledgling administration. Instead, the urban South largely spurned the communists, recoiling in horror from the violence that the Tet Offensive had unleashed. Seizing upon the shift in momentum, American and South Vietnamese units counterattacked. Although characterized by inordinate disregard for civilians caught in the crossfire, the US–South Vietnamese retaliation campaign exacted a heavy toll on the Southern Communist National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong), prompting NLF and North Vietnamese forces to retreat and regroup, and exacerbating North–South tensions within the communist movement. Meanwhile, Thiệu capitalized on the Tet attacks to consolidate power at the expense of his vice president and arch-nemesis Nguyễn Cao Kỳ. Dismissing Kỳ’s backers within the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), Thiệu used accusations of poor performance during the Tet Offensive as a pretext to replace them with loyalists of his own. Though fear of a Nguyễn Cao Kỳ–led military coup would preoccupy Thiệu for the remainder of his term in office, his position as head of state and military commander was secure by the end of the year.

No less significant than Thiệu’s triumph in Saigon’s internecine military squabbles, however, was that the new, year-old constitutional system known as the “Second Republic” had survived the communist attacks intact. Formally inaugurated in April 1967, the Second Republic was founded upon a new constitution with provisions to hold nationwide elections for president, and for representatives in a new National Assembly consisting of a Senate and a Lower House.Footnote 1 These constitutional reforms were intended to stabilize South Vietnam’s turbulent political scene, wracked by years of military infighting, religious conflict, street demonstrations, and a series of regional uprisings following the assassination of former President Ngô Đình Diệm during a military coup in November 1963. Behind the scenes, the South Vietnamese military retained de facto power, which many civilian critics acknowledged to be necessary given a surge in communist momentum following President Diệm’s death. But South Vietnam’s anticommunist political constituents nonetheless hoped that the Second Republic would compel Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu’s military government to address civilian grievances and bind it to the rule of law.Footnote 2 And, at a time when voters in the United States were increasingly beginning to question the prospects and the purpose of intervention in Vietnam, the 1967 reforms also served to alleviate American concerns over chronic instability in Saigon.

Initially, the reforms had been a disappointment in the eyes of the very constituents they were meant to win over. Anticommunist civilian political observers were dismayed, if hardly surprised, by the military’s blatant interference via ballot-stuffing and intimidation to administer the outcome in its favor. But in the aftermath of the brutal Tet campaign, when urban centers directly encountered the violence to which the rural South had long been subject, the legal and political framework ushered in by the Second Republic served as a rallying point for citizens stirred into action by the attacks. Far from evincing public sympathy, the communist offensive instead achieved the unlikely feat of uniting long-antagonistic parties and factions in their outrage and determination to resist a North Vietnamese takeover. A wave of anticommunist solidarity swept through South Vietnam’s cities and provincial towns. Bitter political and religious rivals set aside their differences and formed coalitions to serve in the new National Assembly. ARVN forces took advantage of NLF weakness to expand the Saigon government’s presence into communist-dominated areas in the countryside. This post-Tet spirit of resolution arguably marked the zenith of anticommunist cohesion in Vietnam. And for a time, it appeared plausible that the balance in Vietnam’s decades-long political conflict might be tipping in Saigon’s favor. But as we shall see, in the years that followed, the Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu government squandered this uniquely poised opportunity by moving to monopolize political power at the expense of civilian parties and institutions. Thiệu’s authoritarian turn betrayed the constitutional order on which the state’s legitimacy was based, in turn deflating post-Tet enthusiasm, accelerating American funding cuts, and catalyzing the state’s abrupt collapse from within during a final communist offensive in the spring of 1975.

To date, English-language scholarship on this decisive time period has largely focused on American strategic deliberations and domestic political debates over US troop withdrawal, or diplomatic maneuvering between Washington, Hanoi, Moscow, and Beijing. South Vietnamese political events such as elections, economic reforms, or legislative debates, on the other hand, are rarely afforded much attention in accounts of the war’s final stages. Many historians have dismissed the South Vietnamese state as an American puppet regime, with little autonomy, ideological basis, or popular support. And its ultimate failure has often been regarded as preordained from the outset.Footnote 3 This chapter, however, proposes that, far from American pawns, South Vietnamese political actors played a critical role in determining the outcome of the conflict, pursuing a range of competing agendas and confounding the US Embassy’s attempts to orchestrate events in Washington’s favor. It also asserts the significance of South Vietnam’s volatile political sphere between 1968 and 1975, when anticommunist resolve after the Tet attacks gave way to outrage and despair following President Thiệu’s authoritarian crackdown. In so doing, it suggests that well into the late 1960s, the fate of the Saigon government remained contingent rather than fixed, and that the state’s rapid disintegration in 1975 stemmed largely from the breakdown in domestic political legitimacy that preceded and facilitated the final communist attacks. Despite a sincere if short-lived post-Tet spirit of commitment, the military government ultimately failed to contend with the communists’ formidable rural political network, much less rally and unite urban anticommunists behind a coherent ideological vision. These internal political failures would prove insurmountable, paving the way for the war’s fateful denouement in the spring of 1975.

A Complex Political Landscape

Perhaps the most serious shortcoming in many English-language accounts of the Vietnam War has been a dramatic oversimplification of South Vietnam’s intricate and evolving political geography. Accustomed, perhaps, to regarding Vietnam as merely a component part in the broader Global Cold War, many early historians portrayed the war as a simple binary struggle pitting the Vietnamese communists against the United States and its Vietnamese collaborators. But this approach belies the South’s overlapping political, ethnic, religious, and regional schisms, as well as the extent to which the balance of power between its competing political authorities and parties fluctuated over time. To a far greater extent than in North Vietnam, where the departure for South Vietnam of over 800,000 political and religious émigrés in 1954 facilitated communist consolidation, the South’s political, regional, and cultural heterogeneity posed a considerable challenge to any central authority seeking to enforce state power. An appreciation of this complexity is necessary in evaluating the challenges facing the Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu government as it sought to capitalize on the failed communist Tet attacks.

First, consider the political impact of religion. Perhaps the Saigon government’s most formidable opponents, apart from the communists themselves, were activist Buddhist political groups, particularly the faction led by Thích Trí Quang and associated with the Ần Quang pagoda in Saigon. Representing adherents throughout southern and especially central Vietnam (or northern South Vietnam), the Ần Quang Buddhists drew inspiration from early twentieth-century Buddhist revival movements in South Asia and asserted that Buddhism should be predominant in Vietnamese politics and culture. They were willing and able to stage large-scale rebellions against the central government, hastening former President Ngô Đình Diệm’s downfall in 1963 and temporarily wresting much of central Vietnam from Saigon’s control three years later. This set them apart from a more moderate Buddhist faction headed by Thích Tâm Châu, which was more influential among newly arrived Northerners and more willing to compromise with the South Vietnamese military state.Footnote 4

Vietnamese Catholics, meanwhile, were even more divided by regional tensions. Politically active Southern Catholics were in general more likely to consider peace negotiations and coalition government with their Southern counterparts in the NLF. Often looking to the reformist spirit of the Second Vatican Council (1962–5) for inspiration, they were prominent in South Vietnam’s liberal opposition to military rule and outspoken against Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu’s perceived reliance on hard-line anticommunist Northerners. Northern Catholics, on the other hand, had arrived in the South en masse after 1954. Often informed by firsthand experience of the North Vietnamese state’s own autocratic tendencies, they fiercely resisted compromising with the communist side and could tolerate Thiệu’s mounting authoritarianism, provided he appeared capable of keeping Hanoi at bay. Tightly organized at the parish level, they also wielded disproportionate influence in the Second Republic’s bicameral legislature thanks to a network of disciplined voting blocs.Footnote 5

Elsewhere, in the Mekong River Delta, two small but locally dominant syncretic religious movements, the Hòa Hao and Cao Đài, were regional players in their own right. Subdued by the South Vietnamese military in 1955, they each nonetheless retained a substantial degree of authority over their respective heartlands, where they proved rather more adept than ARVN forces at resisting communist infiltration. Though both were hindered by perpetual infighting between regional and political factions, they wielded considerable influence over large swathes of the Mekong Delta. During the Second Republic, the military government maintained patronage ties with competing Hòa Hao and Cao Đài sections, granting covert cash payments and ceding de facto autonomy in exchange for assistance contesting the communists and delivering votes during national elections.Footnote 6

Further south were the Khmer (ethnic Cambodians), the Mekong Delta’s largest ethnic minority. Resident in the region long before the first ethnic Vietnamese settlers arrived beginning in the seventeenth century, Khmer identity crystallized in the nineteenth century in response to the expansionist and assimilationist policies of the Vietnamese Emperor Minh Mạng. More recently, the French Indochina War (1945–54) had witnessed an explosion of violence between the Khmer and various rival ethnic Vietnamese political and religious groups, resulting in enduring mutual suspicion and animosity. During the Second Republic, most Khmer constituents in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta retained the Khmer language, practiced a different form of Buddhism (Theravada) from their ethnic Vietnamese counterparts (Mahayana), and looked more to Phnom Penh than Saigon as a center of cultural, if not political, authority. Less militarized and with weaker political structures than the Hòa Hao or Cao Đài, they too fought to protect local autonomy in the face of perceived Vietnamese encroachment from both sides of the Cold War divide.Footnote 7 Less numerous but also significant was South Vietnam’s ethnic Chinese population, largely concentrated in Saigon and the towns of the Mekong Delta. Historically dominant in the rice trade, they too retained their cultural and linguistic identity, and were regarded with suspicion by military officials, who feared their allegiance was to Beijing or Taipei rather than Saigon.Footnote 8

To the north, meanwhile, in the Highlands, where central Vietnam meets Cambodia and Laos, a diverse coalition of ethnic minority communities likewise struggled to preserve their cultural and territorial integrity from the competing Vietnamese states centered in Hanoi and Saigon. Loosely united under the mantle of FULRO (United Front for the Struggle of Oppressed Races),Footnote 9 military representatives of the Highlands minorities launched uprisings in 1964 and 1965, protesting the South Vietnamese state’s efforts to assert sovereignty over this strategically vital region by flooding it with ethnic Vietnamese settlers. The rebellions were violently subdued, exacerbating divisions over strategy within the FULRO ranks. Still, given their relative strength in numbers, ability to deliver votes to the highest bidder, and willingness to take up arms if provoked, the Highlands minorities were also a force to be reckoned with.Footnote 10

And then there were the political parties, every bit as fragmented into regional and ideological factions, but still capable of challenging state power, albeit if only within specific provincial districts. Most prominent among them were the Đại Việt (“Greater Vietnam”) Party, and the Vietnamese Nationalist Party (Việt Nam Quốc dân Đảng, or VNQDĐ), loosely modeled on the Guomindang founded by Sun Yat-Sen in republican-era China. By now too weak to replicate the communists’ mass popular movement, the Đại Việts and nationalists instead exerted power by infiltrating the South Vietnamese military and civil service, coming to dominate clusters of towns and rural districts, especially in coastal central Vietnam. That said, by the late 1960s each party was badly divided into antagonistic northern and southern branches, further fragmented in turn into quarreling local leadership factions. Nonetheless, despite their internal divisions, these parties were also significant regional actors, such that district- and province-level appointments and promotions within the South Vietnamese military state were often selected to curry favor with the Đại Việts or VNQDĐ.Footnote 11 Rounding out the picture was a medley of mostly urban civil society groups, including competing trade unions, politicized student organizations, and military veterans’ associations. In common with virtually every other noncommunist entity in the South, these elements were also riven with schisms and infighting. But they too had the power to create chaos when they took to the streets and could leverage the sympathy of influential counterpart organizations in the United States to advance their causes.

Making matters even more challenging for the government in Saigon was the rapid fragmentation of the countryside that resulted from the war’s escalation after President Ngô Đình Diệm’s death in 1963. During the First Republic (1955–63), the writer Võ Phiến described a rural milieu where “newspapers were widely disseminated and went deep into the rural area. … Books would reach as far as the reading rooms of the district offices … and newspapers could go all the way down to the hamlets.”Footnote 12 But as communist momentum swelled, beginning in the early 1960s, transportation and communication between Saigon and the countryside grew increasingly precarious. With control over rural territory now violently contested, official travel between provinces, if not districts, was fraught with peril. Even months after the Tet Offensive, a ground voyage from Saigon to Tân An, the nearest provincial capital to the west, was considered unthinkable for US officials without accompaniment by a military escort.Footnote 13 The result was a rural environment where Saigon’s authority was tenuous and decentralized, and where local officials’ whims took precedence over instructions from the increasingly distant capital. News from Saigon – when it arrived at all – was transmitted more often by rumor through rural grapevines rather than formal public information channels.Footnote 14 These conditions played into the hands of the communists, whose disciplined rural political network allowed them to exert disproportionate power across the countryside at a time when their political rivals were factionalized and confined to isolated regions. Despite being regarded by most American analysts as commanding no more than a plurality of public support in the South, the communists enjoyed a considerable advantage as the country’s only political institution with a nationwide presence, save the South Vietnamese military itself.

Suffice it to say, even as he consolidated his authority over the South Vietnamese military state, President Thiệu still found himself facing a litany of domestic challenges. Worse still, the shock of the Tet Offensive – a clear military defeat for the communists – had shaken the American public’s confidence in the war, with the scale of the attacks casting doubt on years of White House promises that victory was near. The scope and duration of Washington’s commitment was called into question throughout the 1968 US presidential election campaign, which South Vietnamese political observers followed intently. Indeed, should peace candidate Robert Kennedy so much as win the Democratic Party primary, South Vietnamese Intelligence Director Linh Quang Viên warned, it would “weaken the will to fight of the anti-communist people of Vietnam … [and] demoralize our soldiers before the battle is even over.”Footnote 15 True, the communists’ failure during Tet left the South Vietnamese state in a stronger position than it had been since the days of Ngô Đình Diệm’s regime. But even with the NLF on the back foot, South Vietnam remained, to borrow a phrase, an “archipelago state” whose sovereignty was contested across a bewilderingly complex political terrain.Footnote 16 Dominant in cities, scattered military outposts, and a patchwork spread of provincial towns, the government was elsewhere reliant on patronage-brokered alliances of convenience with locally preeminent religious, ethnic, and political groups, united only by their shared aversion to communist rule. Thiệu’s challenge then was to unite these quarrelsome factions and rally them behind a constructive political program capable of surmounting the chronic divisions that rendered anticommunist Vietnam far weaker than the sum of its many parts – and from there, to extend the fledgling Second Republic’s pluralistic constitutional vision into the countryside, building the mass political support necessary to breathe life into its legal structures and to counter the communists’ superior organization, legitimacy, and nationalist appeal.

The Promise of Post-Tet Reform

Given the depth and complexity of the South’s internal divisions, the heartfelt outpouring of anticommunist solidarity after the Tet Offensive was all the more striking. The weeks that followed witnessed a flurry of political organization and engagement. South Vietnamese military recruiters noted a brief but unprecedented wave of volunteer enlistment, particularly among previously indifferent Saigon youths. And political luminaries of all stripes came together to decry the violence. On February 9, for instance, ninety-three intellectuals and cultural figures – including prominent critics of the Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu government – published a statement condemning “the treachery and inhuman action of the Viet Cong, who have dissipated all hope of peace in the people.”Footnote 17 Among anticommunist leaders, the Tet attacks inspired a renewed sense of purpose, and reinforced the urgency of political reform to sustain anticommunist cooperation and momentum.

To that end, representatives from the South’s rival factions took it upon themselves to explore new multiparty coalitions, conscious that in its divided state anticommunist Vietnam was no match for the communists’ rural political machine. Nearly a dozen such efforts burst onto the scene in the spring of 1968, many seeking sanction, if not patronage, from the military government in exchange for grandiose pledges to rally and unite the Southern masses. Among the most prominent was the National Social Democratic Front (NSDF), a loosely organized network that brought together delegates from: two northern Catholic parties; the Central Vietnamese Đại Việt movement; one of two rival Hòa Hao political parties; one of six VNQDĐ splinter groups; and the newly established “Free Democratic Force,” itself a coalition simultaneously negotiating to form a rival bloc, the aptly named “Coalition” [Liên Minh] – an equally intricate confederation connecting the largest trade union with three smaller subcoalitions. Merely to list these overlapping associations and their ever-changing constituent parts was to demonstrate the scale of the challenge anticommunist leaders faced in their bid to forge coherent political institutions. Still, however unwieldy in their execution, these attempts to build working relationships between once-irreconcilable factions were a notable first step in harnessing post-Tet resolve toward constructive ends.Footnote 18

For other aspiring statesmen, however, the most promising approach to fulfilling this post-Tet urgency was not byzantine coalitions but new mass political parties altogether. By far the most successful was the Progressive Nationalist Movement (PNM), led by law professor Nguyễn Vӑn Bông and diplomat Nguyễn Ngọc Huy, the latter a member of the South Vietnamese delegation to the ongoing negotiations between the United States, South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and the NLF in Paris. No party or political organization better embodied the liberal constitutional order promised by the Second Republic than the Progressive Nationalists. Founded in 1969, the PNM was South Vietnam’s most outspoken champion of the 1967 political reforms. It took pains to portray itself as the government’s “loyal opposition,” pledging to support the president on foreign policy and security while offering constructive domestic policy suggestions in the spirit of overall cooperation. Almost uniquely in anticommunist politics, it strove to promote a set of political ideals rather than to represent ethnic, regional, religious, or personal interests. For party elders, the PNM was not primarily a means of wielding power, but rather a vehicle for introducing the broader constitutional system to rural constituents, and for persuading a wavering American public that South Vietnam still merited prolonged support. Though its hierarchy was largely composed of professionals – lawyers, doctors, teachers, journalists, and civil servants – in Saigon and prosperous Mekong Delta towns, the party was committed to building a mass rural base. It also published Progressive [Cấp tiến], among the South’s more reputable daily newspapers, and party cofounder Nguyễn Vӑn Bông even penned an annotated guide to the new constitution, aimed at persuading general readers to embrace the promise of the Second Republic.Footnote 19

To be sure, these efforts were preliminary, and belated. As one PNM organizer conceded, “it takes years to train a doctor and just as long to train a politician. The communists have been training themselves for a long time, and we have only just begun.”Footnote 20 Still, these overlooked examples of organization and resolve after Tet delivered tangible, if ultimately temporary, results. Perhaps the most significant – and unexpected – political development was the abrupt shift in the Ần Quang Buddhists’ approach to the military state. Ần Quang’s protest campaigns had twice brought the Saigon government to its knees, in 1963 and 1966, the latter campaign helping compel the military to concede on civilian demands for elections and a new constitution the following year.Footnote 21 But after Tet, as the intensity of the communist attacks grew clear, the group’s lay hierarchy reconsidered its position relative to South Vietnam’s military authorities. The communist massacre in the city of Huế, in Ần Quang’s central Vietnamese heartlands, had a galvanizing effect, disabusing Ần Quang leaders of the notion that their religious autonomy would be respected under communist rule.Footnote 22 While there was no love lost between Ần Quang and the Saigon generals, whom they regarded as venal, heavy-handed, and incompetent, the Buddhist group increasingly favored its prospects under Saigon’s weak and uneven dominion, rather than risking the communists’ far more capable authoritarianism. Accordingly, Ần Quang surprised political observers by fielding a successful slate of candidates in the 1970 elections for the Senate, an institution it had boycotted in protest three years earlier.Footnote 23 This was a tactical calculation rather than an endorsement of the constitution’s integrity or the state’s legitimacy. But it nonetheless reflected the promise of the South’s brief experiment with constitutional pluralism, as a means of reconciling bitter adversaries behind a working political consensus.

In comparison with the tumultuous years after President Ngô Đình Diệm’s assassination, when religious partisans clashed on the streets, disaffected generals plotted coups, and regional movements sought to escape Saigon’s authority altogether, the change in political atmosphere following the Tet attacks was dramatic. Yet mutual efforts to cooperate were merely the first step, and even then, the process was rarely smooth sailing. Managing functional multiparty coalitions proved more challenging than proclaiming them in the first place. And negotiating a program of political and economic reforms revealed that divisions among South Vietnam’s legislators were nearly as intense as the aversion to communist rule that united them.

Perhaps the most significant area where these long-simmering tensions manifested was the clash between Thiệu and the National Assembly over land reform. Dubbed the “Land to the Tiller” program, the government’s bold nationwide land reform campaign served as a yardstick of its legitimacy, both at home and abroad. Intended to coax war-weary rural constituents back to the fold, it also beguiled South Vietnam’s supporters in the United States, who, then and since, saw land reform as a panacea for the state’s corruption, uneven administrative performance, and thin base of support in much of the countryside. More than any other endeavor, the Land to the Tiller campaign demonstrates both the depth and the limitations of the Second Republic’s reform ambitions. It was also first and foremost a Vietnamese initiative. While popular with American members of Congress, Saigon’s land reform proposals were met with skepticism by American analysts in Vietnam, who feared the fiscal and administrative burden would overwhelm the state’s stretched bureaucracy. Vietnamese officials led by Minister of Agriculture Cao Vӑn Thân were the driving force in designing and implementing the program, belying the notion that South Vietnam was merely an American puppet creation. On paper, Land to the Tiller proposed a radical reordering of the rural economy, breaking up landed estates and redistributing the fields to their former tenants, in turn creating a class of smallholding farmers theoretically beholden to the regime.Footnote 24

A program of this scale required legislative consensus, however, and Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu’s relationship with the Assembly was deteriorating. Recognizing that American congressional aid was increasingly contingent on the progress of the Saigon government’s reforms, the Assembly’s constitutionalists dug in their heels, hoping to extract promises that the president would respect legislative authority in exchange for Land to the Tiller’s timely passage. Matters were not helped when Thiệu then ordered the arrest of three sitting Lower House representatives, breaching their constitutional immunity from prosecution on the grounds that they had offered covert support to the communists. Few legislators were convinced, suspecting that the arrests were politically motivated, if not the product of Thiệu’s personal vendettas against the accused. Deliberations on land reform ground to a halt for months as elected representatives instead used their Assembly pulpit to excoriate the president.Footnote 25 Finally, the legislature relented, and Land to the Tiller was belatedly ratified in March 1970 – albeit over a year after initially intended and with little to show for the delay.

While clearly a constructive offering to rural constituents, Land to the Tiller’s political and economic impact fell short of its proponents’ exuberant aspirations. Indeed, perhaps its most perceptive feature was its restraint. Acknowledging that the communists had long since implemented their own popular land reform experiments in the South, the Saigon government quietly enshrined its adversary’s earlier redistribution efforts, appending legal titles in de facto acknowledgment of prior communist land allocations. This approach wisely defused the animosity certain to ensue should the state dispossess beneficiaries of communist redistribution from land they had long regarded as their own. But it meant that Land to the Tiller’s effect was titular rather than transformative in former communist-held areas, merely reinforcing farmers’ claims to land the enemy had already bestowed on them. And it was not without controversy. Upholding the status quo in contested areas was a bitter pill for the government’s most ardent rural supporters, who, having endured years of violent civil war, now felt that the authorities in the capital were rewarding families who had backed the other side. Military veterans, often compelled away from their land by the government’s own conscription regime, were particularly disaffected, fueling a growing veterans’ protest movement in South Vietnam’s largest cities. Beyond these conceptual complications, implementation of the program was slow and often marred by corruption. Government communications were inconsistent, and, as a result, some farmers continued paying rent to landlords for land they themselves now legally owned. Others complained of land allocations in remote or communist-held areas, where the South Vietnamese military had neither the aptitude nor desire to enforce ownership claims. For ethnic minority groups, particularly in the Central Highlands, the program was a pretext for Vietnamese settlement on their traditional lands. And farmers on the less arable central coast objected to valuations based on the more fertile Mekong Delta, which disadvantaged them relative to their southern peers.Footnote 26 Finally, in addition to land redistribution, the program also introduced new pest- and weather-resistant strains of rice, theoretically capable of boosting crop yields. These necessitated greater quantities of imported fertilizer, however, and skeptics questioned whether increasing farmers’ exposure to currency fluctuations and precarious supply chains was prudent during a brutal ongoing war. Sure enough, as the 1973 Oil Crisis sent fertilizer prices soaring, farmers found themselves at the mercy of their creditors, while unscrupulous officials hoarded fertilizer to sell on the black market or pocketed funds intended to subsidize rural loans.Footnote 27

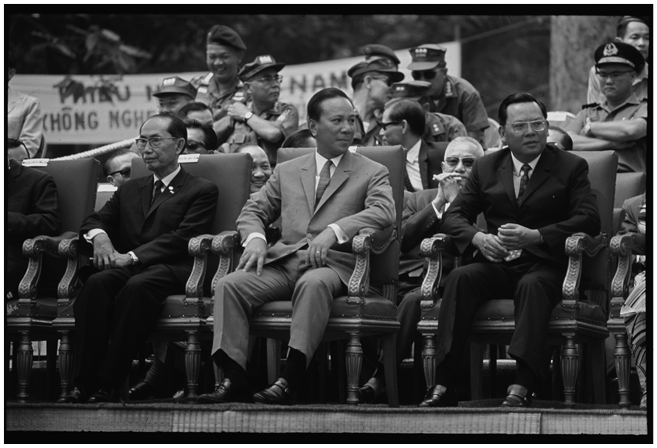

Figure 5.1 South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu, center, with Prime Minister Trần Thiện Khiêm, right (September 15, 1970).

Despite these shortcomings, the Land to the Tiller campaign was a noble effort, testament to the Second Republic’s ambition and early promise. Many farmers benefited, particularly where the program did not overlap with the communists’ earlier interventions. But its political effects were limited, and the economic impact fell short of proponents’ often fanciful expectations. If anything, the greatest beneficiaries were absentee landlords, the recipients of American-backed windfall compensation payments for the expropriation of rural holdings they had little hope of reclaiming.

The Point of No Return

By the end of 1968 the cooperation and purpose that characterized the post-Tet period were already beginning to waver. Anticommunist Vietnam was at its most coherent when facing an imminent communist threat. And as the violence receded, with Hanoi laying low to wait out unilateral American troop withdrawals, the centrifugal forces that had long conditioned politics in the South returned to the fore. The government’s bid to achieve broad legitimacy was threatened by the growing rift between President Thiệu and more moderate elements of anticommunist civil society, including elected legislators, journalists, civil servants, professionals, and other constituents from a largely urban middle class. Bickering between the Assembly and the president on land reform generated resentment and long delays, in turn fueling concerns that Thiệu was isolated, authoritarian, and aloof.

Corruption was another source of mounting alarm. Given poor tax collection rates, persistent inflation, a large fixed-income civil service, and a torrent of American capital pouring into the country, corruption was endemic during the Second Republic. Citizens might be willing to make allowances for poorly paid minor officials, but were incensed at senior figures seen as profiting from the war; as one opposition politician fumed, South Vietnam was “a system whereby a policeman goes to jail for receiving a 100 piastre bribe while a general is exiled to Hong Kong for stealing millions.”Footnote 28 Reducing corruption was therefore an urgent objective during the Second Republic, which even included constitutional provisions for an independent anticorruption inspectorate. Initially, Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu’s dismissal of his rivals’ protégés could charitably be interpreted as a step in the right direction. But his appointment as prime minister of Trần Thiện Khiêm, a well-connected former general whose family controlled Saigon’s ports, signaled to advocates of the constitution that Thiệu was interested merely in building an illicit patronage network of his own. Revelations of state complicity in narcotics-trafficking or the siphoning of military pension funds began to appear in local and overseas headlines. And the anticorruption inspectorate was soon dismissed as little more than a vehicle for silencing Thiệu’s critics.Footnote 29 The situation steadily deteriorated, and by the mid-1970s, as former Foreign Minister Trần Vӑn Đỗ lamented, “Corruption was rampant … the postmen were so corrupt they would steal stamps off the envelopes and resell them. The tax collectors were so corrupt you had to bribe them to accept your tax payments … even a license plate for a vehicle was unobtainable without a bribe.”Footnote 30

Thiệu’s personal excesses in this regard might have been forgiven, had he been seen as responsive to constituents’ concerns, and willing and able to rally anticommunist Vietnam behind a constructive vision. But representatives from the newly formed post-Tet political coalitions soon complained of insufficient presidential direction, much less enthusiasm, and these once-promising alliances quickly lapsed or disintegrated altogether. In fact, as one of Thiệu’s closest advisors later admitted, American funds to promote the NSDF and other multiparty networks had instead been plundered for government officials’ personal use.Footnote 31 Rather than mend fences with Assembly moderates following the bruising land reform confrontation, the president continued lashing out, arresting the legislature’s most outspoken critics on trumped-up charges in defiance of their constitutionally mandated immunity. The incarceration of Lower House representative Ngô Công Đức in May 1971 went too far even for the reliably progovernment newspaper Political Discussion [Chính Luận], which denounced his detention as “a black scar on our so-called legally based democracy.”Footnote 32

Quietly, Thiệu was already plotting to subvert the Assembly, opting for short-term expediency ahead of popular legitimacy and consensus. During the 1970 midterm elections, most observers focused on the race for Senate where, by all accounts, the contest proceeded relatively free from government interference.Footnote 33 Arguably, the Senate elections represented the high-water mark for electoral integrity in Vietnam, then and since. But Thiệu and his advisors had noted that though the Senate enjoyed more prestige, it was the weaker of the two chambers in practice, as its resolutions could be overturned with a two-thirds majority in the Lower House. With attention focused on the Senate, Thiệu made his move, seizing de facto control of the Lower House through a torrent of bribery and behind-the-scenes manipulation of its leadership elections. Well-regarded and generally progovernment independent Nguyễn Bá Cẩn was ousted as Lower House Chairman, replaced by Nguyễn Bá Lương, whom the US Embassy described as “totally subservient to the wishes of the executive.” Amidst further allegations of bribery published in the PNM’s newspaper, Progressive, Thiệu’s preferred nominees in the Supreme Court also prevailed, paving his way to rewrite the rules of the upcoming 1971 presidential election as he saw fit.Footnote 34 Liberal constitutionalists began to despair. In 1971, Nguyễn Vӑn Bông, the man who, as cofounder of the PNM, was perhaps most closely associated with the aspirations of the Second Republic, updated his annotated guide to the constitution. His new preface struck an ominous tone: “The essence of the constitution has not been fostered,” he warned, “and going further, democratic spirit has not become ingrained in the consciousness of our ruling class. The people’s voice is critical in the struggle for a democratic environment, but our actions and thoughts have not yet transcended the childish maladies of colonial times.”Footnote 35

It was hardly a surprise, then, when Thiệu, brandishing control of the Lower House and the Supreme Court, imposed legislation tailor-made to deliver his reelection. Unlike the chaotic, if relatively unrestricted, 1967 contest, the opposition was now deemed eligible only after securing at least 40 or 100 endorsements respectively from Assembly representatives or province-level councilors. As Thiệu had personally appointed or purchased the loyalty of most potential signatories, the law was seen as tantamount to a presidential veto against his prospective opponents. It was met with howls of outrage, such that the Political Discussion newspaper speculated whether constitutionally minded senators might demonstrate in front of their own Assembly against the “childish and despicable” bill.Footnote 36 Merely winning reelection, however, was just the first step for Thiệu and his advisors. The 1971 contest was their opportunity to radically transform South Vietnamese politics, streamlining decision-making under the authority of a powerful executive and neutralizing the opposition’s ability to interfere. The early post-Tet attempts at multilateral consensus were discarded, to be replaced by a covert network of loyalists operating from within the military bureaucracy. And the first test of their abilities and commitment was to administer for Thiệu a decisive victory. To that end, the president’s team tasked rural henchmen with “mobilizing the election of the president and supporting Lower House candidates.” Key to the operation were Thiệu’s “submerged” partisans, encouraged to “corner and paralyse the opposition blocs by exploiting blemishes … [such as] undesirable behaviour that can be used to threaten potential recruits with prosecution.” Opposition supporters were to be harassed, threatened, or even forcibly relocated away from their villages as a means of “forcing them to follow us, or at least preventing them from daring to work for the opposition.” Teachers, civil servants, soldiers, and police were to be targeted, with the latter considered especially effective at “submerged activities, in particular, cornering and paralysing the opposition.”Footnote 37

But copies of Thiệu’s vote-rigging instructions inevitably leaked, prompting one province chief to bemoan that the president had “put in writing what should have been done orally.”Footnote 38 Rather than dignify a contest whose outcome was clearly prearranged, the two opposition candidates, Dương Vӑn Minh and Thiệu’s longtime nemesis, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, both dropped out in protest. Thiệu was undeterred, rebranding the one-man election as a referendum on his fitness to rule. The US Embassy howled with disapproval. Political moderates joined students and veterans on the streets to express their outrage. And some of Saigon’s most committed American allies withdrew their support in disgust, including arch anticommunist Senator Henry Jackson. In a sign of things to come, the US Senate pointedly shot down a proposed $565 million supplemental aid bill for South Vietnam, just days after the uncontested reelection. Thiệu’s ambassadors in Washington had warned for years that congressional support was conditional, and limited; now, the bill for his authoritarian turn was coming due.Footnote 39

With reelection now inevitable, Thiệu accelerated his consolidation of power. Using the pretext of renewed communist attacks in the spring of 1972, he deployed the Lower House to ram through sweeping emergency legislation, effectively proscribing independent political parties and chastening opposition newspapers with the threat of debilitating legal challenges. Then, in late 1972, Thiệu’s “submerged” political structure went public, formally inaugurated as the “Democracy Party” – though the descriptor was hardly apt. Critics condemned a compulsory membership scheme for government workers, and its structural similarities to the Vietnamese Communist Party were widely noted. Civil servants and soldiers who refused to participate faced dismissal, if not prosecution, on trumped-up charges; civilian bureaucrats were threatened with military conscription or transfers to insecure communist-controlled areas. A wave of public officials resigned in protest, including well-regarded military commander Nguyễn Bé, who excoriated the Democracy Party as “intended simply to perpetuate President Thiệu in power … [with] no greater national purpose and no independent ideology that will appeal to the Vietnamese people.”Footnote 40

Growing revulsion toward Thiêu’s authoritarianism helps explain the markedly different response in urban South Vietnam to renewed communist violence in 1972. Unlike the 1968 Tet attacks, which, as we have seen, inspired a fleeting burst of cooperation and engagement with the state’s new political institutions, North Vietnam’s 1972 Offensive instead aggravated the South’s internal divisions. Perhaps counterintuitively, political tensions mounted even as the South Vietnamese military performed well in isolated instances. At the town of An Lộc, situated on a strategic corridor connecting Saigon with northeastern Cambodia, ARVN forces unexpectedly held the line as overwhelming American firepower ground down the communist advance on the capital.Footnote 41 But the government struggled to deploy An Lộc as a rallying cry, not least owing to the poor quality of its public information. State censorship of ARVN setbacks such as the fall of Quảng Trị province “has become a subject of ridicule to Saigonese,” the US Embassy reported, and even staunch government supporters despaired as the state’s credibility eroded. “No one believes government radio and TV any more,” lamented Thiệu-loyalist Phạm Anh, Chair of the Lower House Foreign Affairs Committee. “People [get] most of their news from Voice of America, BBC, and rumor.”Footnote 42 Cynicism and distrust abounded, compounding Thiệu’s efforts to again invoke the 1968 Tet Offensive to his advantage.

With the prospect of a peace settlement looming, Thiệu’s sacrifice of popular legitimacy for the expediency of authoritarian rule left South Vietnam exposed on multiple fronts. By now, American military withdrawal was nearly complete. Political observers in Saigon looked anxiously toward Washington, anticipating a diplomatic breakthrough with Hanoi in time to secure Richard Nixon’s reelection in November. Excluded from secret US–North Vietnamese negotiations, the South was always vulnerable to unilateral American concessions. And sure enough, the United States blinked first, allowing North Vietnamese troops to retain their positions in South Vietnamese territory as a precursor to securing a peace deal. Thiệu’s inner circle was incensed. But while the president and his entourage were taken aback by Washington’s terms, they could hardly claim to have been surprised. Indeed, advisors like Hoàng Đức Nhã – at Thiệu’s side during the confrontation with Kissinger – had warned for years that action on “corruption and social justice” was imperative for “improving the attitudes of the American people towards Vietnam.”Footnote 43 After all, as Father Trần Hữu Thanh, the militantly anticommunist leader of the dissident People’s Anti-Corruption Movement, had warned, “Foreign aid to Vietnam is being withdrawn because the aid does not go to the people and does not truly help the nation, as it is completely siphoned off by corruption. No country wants its good will to enrich an oppressive minority, and no country is satisfied pouring money into a bottomless pit.”Footnote 44 Thiệu stalled for time until after Nixon’s reelection. North Vietnam feared a ruse and withdrew from the negotiations. Nixon responded with a widely condemned American bombing campaign against Hanoi, meant to reassure Thiệu as much as punish the communists. But he also threatened South Vietnam with devastating aid cuts, lest Thiệu remain defiant. With little choice but to relent, Saigon begrudgingly submitted, to terms which disappointed American negotiators. As one US official recalled, “We bombed the North Vietnamese into accepting our concessions.”Footnote 45

Sweeping congressional cuts to American military aid soon followed – an explicit response to Thiệu’s unopposed reelection and moves against the legislature, judiciary, independent parties, and the press. Between fiscal years 1973 and 1974, United States military assistance to South Vietnam shrank from $3.3 billion to $941 million, a 72 percent reduction. Yet the scale of the cuts notwithstanding, American contributions to Saigon’s war effort remained substantial: $941 million in military aid for fiscal year 1974 was still 42 percent more than what the United States had provided in fiscal year 1967. And if Congress was no longer willing to indulge a bloated and authoritarian military government in Saigon, it remained generous in allocating funds to causes it deemed more worthy. Nonmilitary economic aid to South Vietnam was expanded by 23 percent during fiscal year 1974, including a ten-fold increase in support for internally displaced civilians. Moreover, cuts to military assistance beginning in 1973 had been preceded by equally dramatic spikes, with an overall increase of 112 percent from fiscal year 1970 spending levels.Footnote 46 In 1972 alone, the Nixon administration gifted some $2 billion worth of fuel, supplies, and military hardware, to compensate for looming congressional spending cuts. Intended to coax Thiệu into accepting Nixon’s peace terms, the splurge also helped him reinforce his command over the military by enabling lavish patronage distribution, tempering political fallout from the American settlement with North Vietnam. But in military terms, it was not American firepower but Vietnamese leadership that was needed. Despite now boasting the world’s fourth-largest army and air force, and fifth-largest navy, thin leadership, poor morale, rampant desertion, and insufficient technical expertise meant that, relative to the communists, South Vietnam remained, according to one Pentagon official, “an expansion team going against the league champs.”Footnote 47

The Vietnamese communists, on the other hand, were – whatever else – tenacious and ruthlessly effective rural organizers. Following the peace settlement, they stepped up infiltration of the South and competed for control of the rice harvest. Before long, villages assumed to be safely under Saigon’s control were revealed to have sustained covert communist networks all along. One official spoke of his chilling experience, on awaking one morning, of witnessing the houses in every hamlet in his officially “secure” district now suddenly displaying a communist flag.Footnote 48 Equipped for mechanized, high-tech warfare, South Vietnamese forces often struggled to respond to their adversary’s revised tactics. Their massive American weapons transfers were ill-suited for rural political competition and, if anything, reinforced the worst tendencies of the ARVN top brass. Where communist cadres were nimble, calculating, and frugal, ARVN relied on gratuitous firepower, an approach that proved both counterproductive and wasteful. Oriented and equipped for battlefield confrontation, the South Vietnamese military state too often lacked the aptitude and civic institutions required to prosper in rural political competition. Had Thiệu succeeded in assembling a mass rural organization, he might well have withstood the communist challenge and the dissolution of his urban support base. But his assumptions about the countryside were romantic, if not grandiose, and he overestimated his influence over and appeal to rural citizens. An aspiring authoritarian populist, he lacked moral authority and was unpopular. As we have seen, the political impact of the state’s much-trumpeted land reforms was tepid. Soaring fertilizer prices in the mid-1970s further immiserated the rural South. And with farmers abandoning government-controlled urban slums and returning to their fields after the 1973 peace settlement, the assumption that Thiệu’s rural agenda had achieved lasting loyalty to the state proved largely illusory.

Conclusion

Five years after the failure of the 1968 communist Tet Offensive, the Saigon government’s momentum had been squandered. An initial outpouring of urban resolve had long since dissipated, giving way to fury and despair over Thiệu’s obliteration of the 1967 constitutional order. Thiệu consoled himself by imagining a captive base of support in the countryside. But the political impact of his agrarian reforms was limited, and the state had made little progress building grassroots institutions with which to contest the communists by attracting rural constituents to its side. Meanwhile, across the border, the North Vietnamese military was busy preparing yet another all-out offensive against the South. They were not expecting an easy victory. Mounting tensions with the Soviet Union and especially China meant that future military aid to Hanoi was uncertain. And despite inconsistent leadership, poor morale, chronic desertion, and the rapid depletion of its ammunition stocks, the South Vietnamese military remained large and well-equipped, at least on paper. When the North Vietnamese Politburo met in October 1974 to plan the invasion, they anticipated that success in the South would require at least two years of intense fighting – and even this projection was based on the most favorable assumptions.Footnote 49

What followed in the spring of 1975 was less a battlefield defeat than the disintegration of the South Vietnamese state from within. Communist forces began by probing remote South Vietnamese outposts in the Central Highlands, testing the Saigon government’s capabilities and intentions. The ARVN defenders wilted, and, no less important, there was no indication in Washington that the United States might intervene. Then, on March 11, Thiệu issued fateful orders. Reasoning that ARVN forces were overstretched, he announced a tactical withdrawal from the Highlands, to prioritize protecting the more densely populated central coast. But the retreat quickly deteriorated into a rout. Low on confidence and lacking faith in the government’s ability to deliver, ARVN forces and their commanders panicked. Discipline broke down, prompting thousands of civilians to join the departing soldiers in their flight for the coast. Indiscriminate communist artillery fire added to the mounting sense of terror. As news of the debacle in the Highlands reached the coast, ARVN soldiers abandoned their posts, discarded their uniforms, and melted away into the convulsing civilian crowds. In Đà Nẵng, the second-largest city in the South, an estimated 60,000 people perished while attempting to flee, many after drowning in the clamor to board makeshift escape boats.Footnote 50 “Đà Nẵng was not captured,” one observer recalled, “it disintegrated in its own terror.”Footnote 51 Fear and anarchy cascaded south, along the coast. ARVN forces held out bravely at Xuân Lộc, along the main highway east of Saigon, but it was not enough.Footnote 52 On April 20, Thiệu himself jumped ship, resigning during a tearful televised press conference before departing to Taiwan. Ten days later, communist tanks crashed through the gates of his palace, bringing the decades-long conflict to a dramatic end.

South Vietnam’s turbulent political trajectory after the Tet Offensive has been largely overlooked in most early English-language accounts of the Vietnam War. Yet it was during these decisive years that the political fate of the South Vietnamese state was sealed. Far from an American puppet regime, the South was led and contested by a diverse range of Vietnamese protagonists, divided by religion, ethnicity, and partisan affiliation, but determined to assert themselves, often in defiance of the United States. Nor, until the final weeks, did its astonishingly abrupt internal collapse ever seem preordained. Far more than on the battlefield or in diplomatic negotiations, the outcome of the conflict hinged on the state’s failure to achieve political legitimacy, even in the eyes of its most committed anticommunist constituents. Extravagant corruption and unwillingness to abide by constitutionalist principles corroded public trust. And when civilians and soldiers alike lost faith in Thiệu’s ability to marshal the state in their defense, the ensuing nationwide erosion of political confidence precipitated Saigon’s rapid military capitulation.