The Patron of the Royal College of Psychiatrists has pointed out the irony involved in recording patients' religion, without seeking to discover that all this means to them in terms of understanding and coping with their illness (HRH The Prince of Wales, 1991). One College past-President (Reference SimsSims, 1994) firmly recommends evaluating the religious and spiritual experiences of our patients in assessing aetiology, diagnosis, prognosis and planning treatment. Across the water, an American Journal of Psychiatry editorial (Reference AndreasenAndreasen, 1996) has it that, ‘We must practice and preach the fact that psychiatrists are physicians to the soul as well as the body.’

The World Health Organization (WHO) involved more than 30 collaborating centres in the development of its instrument for measuring quality of life, the WHO Quality of Life (WHOQOL), which is structured by six domains (Box 1). A report on the proposed spirituality, religious and personal beliefs (SRPB) domain (WHO, 1998) quotes the WHO Constitution's definition of health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease’. It continues (p. 7):

Box 1 The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) domains

Physical health

Psychological health

Level of independence

Social relationships

Environment

Spirituality, religion andpersonal beliefs

‘Until recently the health professions have largely followed a medical model, which seeks to treat patients by focusing on medicines and surgery, and gives less importance to beliefs and to faith – in healing, in the physician and in the doctor–patient relationship. This reductionism or mechanistic view of patients as being only a material body is no longer satisfactory. Patients and physicians have begun to realise the value of elements such as faith, hope and compassion in the healing process. The value of such ‘spiritual’ elements in health and quality of life has led to research in this field in an attempt to move towards a more holistic view of health that includes a non-material dimension (emphasising the seamless connections between mind and body).’

These ideas are supported by a clear and persuasive trend in the nursing literature (Reference NarayanasamyNarayanasamy, 1993; Reference RossRoss, 1994, Reference Ross1996; Reference McSherry and DraperMcSherry & Draper, 1997; Reference Nolan and CrawfordNolan & Crawford, 1997; Reference McSherryMcSherry, 1998; Reference Greasley, Chiu and GartlandGreasley et al, 2001). The strong suggestion emerges that spiritual care and psychiatric treatment must, of necessity, go together.

Definition of spirituality

What is spirituality? How does it relate to religion? What is the distinction between healing and cure, and how may this be relevant to multi-disciplinary psychiatric practice? How has spirituality been researched? What are some of the findings? How may a person's spiritual needs be assessed? What knowledge, skills and attitudes pertaining to spirituality can be taught? Could they benefit clinicians as well as patients? These are among the questions addressed in this paper.

Encountered in various ways in all human beings, spirituality is a common human phenomenon. The WHO (1998) proposes 18 facets for the WHOQOL SRPB module, under four headings: transcendence, personal relationships, code to live by and specific religious beliefs (Box 2).

Box 2 Facets proposed for a World Health Organization Quality of Life Spirituality, Religious and Personal Beliefs module

Transcendence

Connectedness to a spiritual being or force

Meaning of life

Awe

Wholeness/integration

Divine love

Inner peace/serenity/harmony

Inner strength

Death and dying

Detachment/attachment

Hope/optimism

Control over your life

Personal relationships

Kindness to others/selflessness

Acceptance of others

Forgiveness

Code to live by

Code to live by

Freedom to practice beliefs and rituals

Faith

Specific religious beliefs

Specific religious beliefs

These 18 facets helpfully outline the territory. An often-quoted definition, more practical for everyday use, comes from Murray & Zentner (1989: p. 259):

‘In every human being there seems to be a spiritual dimension, a quality that goes beyond religious affiliation, that strives for inspiration, reverence, awe, meaning and purpose, even in those who do not believe in God. The spiritual dimension tries to be in harmony with the universe, strives for answers about the infinite, and comes essentially into focus in times of emotional stress, physical (and mental) illness, loss, bereavement and death.’

Ellison (1983) suggests that spirituality

‘enables and motivates us to search for meaning and purpose in life. It is the spirit which synthesizes the total personality and provides some sense of energizing direction and order. The spiritual dimension does not exist in isolation from the psyche and the soma, but provides an integrative force. It affects and is affected by our physical state, feelings, thoughts and relationships. ’

Dimensions of human experience

The spiritual dimension of human experience can be described as one of five interrelated dimensions. In Box 3 these are displayed as a hierarchy, suggesting (in bold) how the disciplines of general medicine, psychiatry and religion each relate principally, in an overlapping fashion, to the five dimensions.

Box 3 Dimensions of human experience

Dimensions of experience Principally related disciplines

Spiritual Religion Psychiatry

Interpersonal (familial/sociocultural) Religion Psychiatry

Intrapersonal (psychological) Religion Psychiatry General medicine

Biological (organic)Psychiatry General medicine

Physical General medicine

In many cosmologies, the spiritual dimension is the most complex, subsuming and inhabiting the other four in a seamless and integrative fashion. It is the source of the remainder – of time, space and everything else – thus rendering the system circular and dynamic, a poetic and mandalic vision of wholeness. Paradoxically, by virtue of its unity and indivisibility, it is also the simplest dimension.

Spirituality with reference to a shifting paradigm

In support of the WHO report, Capra (1983), Ravindra (2000) and many other commentators (e.g. Reference LorimerLorimer, 1998) have suggested that Western culture is undergoing a significant paradigm shift – from a materialist view, based on the assumptions of dualism, rationalism, positivism and empiricism, towards a naturalistic understanding that acknowledges the significance of such things as personal stories, emotions and experiences that cannot be explained purely in terms of science.

People are moving away from self-centred individualism towards a recognition of the fundamental wholeness and interconnectedness of human beings, indeed the whole of time and creation (Reference FindlayFindlay, 2000; Reference PowellPowell, 2001).

According to Capra (1998), reductionist and mechanistic explanations are giving way to more holistic and ecological ways of interpreting the world. Chaos and complexity theories are already being considered within health care (Reference Plesk and GreenhalghPlesk & Greenhalgh, 2001). Consciousness studies (Reference LorimerLorimer, 1998, Reference Lorimer2001), including investigation of the healing effects of prayer (Reference DosseyDossey, 1993) as well as so-called ‘peak’ experiences (including past life, out-of-body and near-death experiences), also have relevance to psychiatry without yet being integrated within the discipline. These new ways of understanding human experience point positively towards the new paradigm and promote the concept of a non-material or spiritual dimension to life.

Clinical, training and research issues

For some patients within mental health settings, religion and spirituality are already emerging as relevant factors in research and clinical care (Reference Koenig, McCullough and LarsonKoenig et al, 2001). For example, a fairly typical survey by Lindgren & Coursey (1995) of 28 ‘seriously ill’ psychiatric patients from a rehabilitation centre, with diagnoses including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, schizoaffective disorder and personality disorder, found that 60% reported that religion/spirituality had ‘a great deal’ of helpful impact on their illness through the feelings it fostered of being cared for and of not being alone. In addition, 76% thought daily about God or spiritual matters.

Spirituality does not fit easily with our understanding of science and what constitutes the scientific truth and there has been a tendency for psychiatry to exclude the significance of spirituality, other than as a form of pathology or pathological response. In Lindgren & Coursey's (1995) study, 38% of patients expressed discomfort with mentioning their spiritual or religious concerns to their therapist, a finding backed up by the Mental Health Foundation (Reference FaulknerFaulkner, 1997). Swinton (2000) writes:

‘While spirituality remains a peripheral issue for many mental health professionals it is in fact of central importance to many people who are struggling with the pain and confusion of mental health problems [p. 7] … It is possible simply to dismiss the idea of the spiritual as unscientific and therefore unworthy of serious consideration with regard to the therapeutic process. However, one would be wise to consider the evidence for the benefits of including the spiritual dimension within caring strategies [p. 39] … It is potentially central in the enabling of mental health, even in the midst of deeply disturbing forms of mental illness [p. 9].’

Neelman & King's (1993) survey of 200 London psychiatrists found that 90% viewed religious beliefs as relevant to patient mental health, ‘to be considered during assessment and therapy’. Glas (2001), a consultant psychiatrist and professor of philosophy, also follows others from within nursing, such as Ross (1996) and McSherry & Draper (1997), by firmly recommending the education of mental health professionals on spiritual issues in terms of attitudes, knowledge and skills.

Greasley et al (2001) quote a Health Education Authority publication (1999) that emphasises the importance of spiritual beliefs as a source of comfort and support in times of crisis. Sloan et al (1999) report widespread support for the positive influence of religious and spiritual beliefs on health and well-being. Also, official advice appears in an appendix to Good Psychiatric Practice (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2000: p. 41), as follows:

‘Good practice in general adult psychiatry will include: taking a direct care role which involves assessment of mental health problems … and being cognisant of the spiritual and cultural needs of patients and their carers …understanding and referring appropriately in respect of social, spiritual or cultural interventions' (my emphasis).

The distinction between healing and cure

The influence of the medical model, with its assumptions of cause and effect, specific aetiology, diagnosis and appropriate treatment, leads to an understanding of mental health as simply the absence of mental illness. According to Trent (1999) the assumption is that if people are not ill, they must by default be healthy. The new paradigm argues differently.

Swinton (2001: p. 57) says that ‘strategies and understandings that seek to cure mental health problems are obviously valid and should be encouraged. However, the reality for a significant number of people is that certain forms of mental illness are interminable’. Borrowing from medical anthropology, he notes that cure has to do with the eradication of disease. It is the anticipated outcome of attempts to take control of disordered biological and/or psychological processes.

Healing, derived from Saxon and high German words for ‘whole’, is more than ridding a person of particular symptoms or difficulties. It relates to that aspect of care that attends to the deep inner structures of meaning, value and purpose that form the infrastructure to all human experience. Swinton (2001: p. 57) calls healing ‘a deeply spiritual task that stretches beyond the boundaries of disease and cure’.

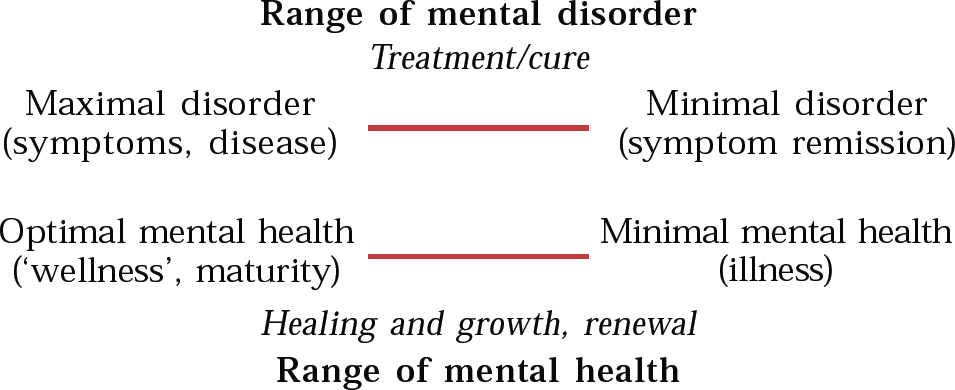

Tudor (1996) helpfully suggests understanding mental health in terms of two continua: a mental disorder/cure continuum and a mental health/healing continuum (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Health within illness, the two continua model (from Reference TudorTudor, 1996, with permission)

The former focuses on pathology and severity of illness in the conventional way, informed by the medical model. The latter focuses on issues such as degree of contentment, joy, inner peace and emotional equanimity as well as maturity, relationships, social functioning, degree of disability, sense of meaning and purpose (hence motivation) and so forth.

Mental health can, therefore, be defined in terms of the whole person and understood in terms of growth and personhood. In writing about this, Swinton (2001) echoes Fowler (1981) who, drawing on the works of Jean Piaget, Erik Erikson and Lawrence Kohlberg as well as his own extensive research, mapped out human psychological development as ‘a quest for meaning’ through six ‘stages of faith’. Mental health care can thus be viewed in terms of persons being provided with encouragement, adequate resources and a conducive environment to enable them to grow as unique individuals (Box 4).

Box 4 Elements of spiritual care

An environment for purposeful activity such as creative art, structured work, enjoying nature

Feeling safe and secure; being treated with respect and dignity and allowed to develop a feeling of belonging, of being valued and trusted

Having time to express feelings to staff members with a sympathetic, listening ear

Opportunities and encouragement to make sense of and derive meaning from experiences, including illness

Receiving permission and encouragement to develop a relationship with God or the Absolute (however the person conceives of what is sacred), thus a time, place and privacy in which to pray and worship, education in spiritual (and sometimes religious) matters, encouragement in deepening faith, feeling universally connected and perhaps also forgiven

This approach resonates well with attitudes already prevailing and promoted within rehabilitation psychiatry. Shepherd (1991), for example, writes:

‘Interventions which emphasize the importance of helping the person make sense of their experience, help them integrate their functioning [p. 4] … improve engagement in daily activities, etcetera, may all be seen quite legitimately as “treatments” in their own right [p. 10].’

Religion or spirituality?

This is an important question, because both health care practitioners and early researchers have tended to equate the two. According to Narayanasamy (1993) this results in ‘nurses identifying spiritual care as the exclusive realm of chaplains or religious agents’; furthermore, ‘many carers steer clear of spiritual material for fear they are unqualified, ill-equipped, or because they simply feel it is not part of their job description’. In a study quoted by Nolan & Crawford (1997), of 176 nurses, only 11% felt able to provide spiritual care for their patients. These authors, referring to the different dimensions of human experience, remark that all religions embrace spirituality, but religion is only one of a variety of ways of understanding or accessing it.

The WHO report (1998) referring to the facets proposed for the WHOQOL SRPB module (Box 2), suggests that the areas covered are common to people coming from many different cultures and holding different beliefs. It acknowledges that some people follow a particular religion, that others do not follow a particular religion but believe in a higher spiritual entity, and still others do not follow a religion or believe in a higher spiritual entity but do have strong personal beliefs that guide them in their day-to-day activities (such as scientific theory or a particular philosophical view). Each will look at the WHOQOL SRPB ideas and statements with their particular belief system in mind, and allowance has been made for this.

In a focus group study, Greasley et al (2001) asked the question, ‘Is there a difference between spiritual care needs and religious care needs?’ They reported the majority of study participants as seeing and emphasising the two as distinct, arguing that a person does not have to adhere to a particular set of religious beliefs or practices to have spiritual beliefs and needs of a more individual and personal nature. There was concern that, where spirituality is perceived to be synonymous with religious beliefs and practices, a patient's spiritual needs might not be addressed when he or she does not express any religious affiliation.

Research into spirituality

Conventional (empirical) research

Systematic reviews of the research literature have consistently reported that aspects of religious and spiritual involvement are associated with desirable health outcomes (Reference SwintonSwinton, 2001, p. 68). Spirituality has been positively correlated with symptom reduction in depression, anxiety, addictions, suicide prevention, anorexia and schizophrenia.

Acknowledging that the human spirit may not be measurable as an independent variable, King (see Reference GlasGlas, 2001) suggests, however, that even without knowledge of its content, the strength of a person's religious or spiritual belief can be measured. Perhaps more important, the impact or salience of a spiritual belief to life and its effect on behaviour is measurable using, for example, the Royal Free Interview for Religious and Spiritual Beliefs (Reference King, Speck and ThomasKing et al, 1995).

In spite of acknowledged problems, the authors of the authoritative Handbook of Religion and Health (Reference Koenig, McCullough and LarsonKoenig et al, 2001) have conducted a critical, systematic and comprehensive analysis of empirical research, examining the relationships between religion and a variety of mental and physical health conditions, covering more than 1200 studies and 400 research reviews. Careful to try to distinguish religion from spirituality, the authors have written general chapters on the positive and negative effects of these, as well as on the patient's subjective experience. There follow specific chapters on mental well-being, depression, suicide, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia and other psychoses, alcohol and drug use, delinquency, marital instability and personality, as well as on research methods, measurement tools and areas of research needing further study.

Koenig et al (2001) comment that, from a scientific perspective, the question of religion's effects on health is an important one that has yet to be fully answered. This is partly due, they say, to the main preponderance of studies being on subjects from the USA, Europe or Israel, and from traditional Christian or Jewish backgrounds, adding that research with Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists is relatively rare, difficult to access and hard to interpret. The authors conclude firmly, nevertheless:

‘Research has shown that medical patients have religious and spiritual needs that are intimately related to their physical health conditions, and that religious and spiritual beliefs and practices can often be important for emotional healing’ (Reference Koenig, McCullough and LarsonKoenig et al, 2001: p. 591).

Appropriately supportive of the empirical approach, they add that the fields of psychoneuroimmunology and psychosomatic medicine have shed light on the physiological mechanisms by which psychological, social and behavioural factors can affect health and well-being.

New paradigm research

According to Dixon-Woods & Fitzpatrick (2001), referring to recently published guidance from the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, increased recognition has now officially been given to diverse types of evidence that can, perhaps should, contribute to systematic reviews. Qualitative research has established a place for itself.

This is helpful and may be further evidence for the paradigm development in both science and health care. We are moving beyond positivism, which limits knowledge to observable facts, and empiricism, which regards nothing as true, save what is given by sense experience or by inductive reasoning from sense experience (Reference Honer and HuntHoner & Hunt, 1987), towards a ‘participant–observer’ type of approach (Reference LorimerLorimer, 1998) and constructivism – whereby observation is assumed to be value-laden, thus an interpretative process (Table 1).

Table 1 Contrasting traditions and new paradigms (personal communication, P. Fenwick, 2002)

| Context | Traditional perspectives | New paradigm perspectives |

|---|---|---|

| Models | Reductionist, positivist, empiricist, dualistic, mechanistic | Participant—observer, constructivist, holistic, ecological |

| The nature of the world | Everything is composed of physical matter | The human world is emergent and non-local. Realities appear to be multiple and overlapping |

| World views | Objective: the outside is seen as the only reality | Simultaneously subjective and objective: inner and outer reality are experienced as interconnected and indivisible |

| Values | The world is seen as value-free, independent of the observer | The world is value-laden and has intrinsic meaning; interpretations necessarily reflect this |

| Causal relationships | Reality is causally based in time-linear fashion | Causes can arise outside the system, acting through non-local effects |

| The possibility of general laws | General laws generated are universally valid | “Laws” are based on assumptions (often hard to verify), and are limited to each unique and changing set of interdependent circumstances |

In a study of spirituality and depression Swinton (2001: p. 99) has used the methodology of hermeneutic phenomenology, which asserts that the (phenomenological) facts of lived experience are always already meaningfully (hermeneutically) experienced.

Data were collected using unstructured, in-depth interviews on six subjects, who had each experienced depression for at least 2 years. Each interview was initiated with the question, ‘What is it that gives meaning to your life?’ Interview texts were entered into a software program designed to facilitate analysis. The 10-stage research process involved production of a rich description of the depression experience, with both independent and participant validation, and it was completed by the research product being fed back to the participants, their thoughts and comments being taken into consideration in the final account.

Swinton lists eight central themes of spiritual significance emerging from the data (Box 5). He describes the ways in which participants use their spirituality to restore meaning, purpose and hope to their lives under two headings: the healing power of understanding; and liturgy and worship. All participants were volunteers, committed to the Christian faith tradition and interested in spirituality. This is an acknowledged limitation of the study.

Box 5 Central, spiritually relevant themes in depression (Reference SwintonSwinton, 2001)

The meaningless abyss of depression

Doubt and the questioning of everything

Abandonment, by God and other people

Clinging on, through faith

The continuing desire to relate to others while relationships fail

Exhaustion, demoralisation and feeling ground down

Feeling trapped into living

The crucible of depression – a transformative (and ultimately beneficial) experience

Caveats accepted, this innovative methodology successfully reveals and emphasises the relevance of spirituality in mental health care. The methodologies of the questionnaire studies of Narayanasamy (1993), Ross (1994) and McSherry (1998), the questionnaire-plus-interview study of Nathan (1997), the focus group study of Greasley et al (2001) and the narrative-based approach identified by Roberts (2000) point in a similar direction.

Spiritual needs and spiritual care

According to Greasley et al's (2001) study, ‘the domain of spirituality is a vital concern for the majority of service users’. Nevertheless, ‘participants felt that spiritual needs are not a priority for medical staff relative to more tangible issues of care’. It was therefore suggested that training programmes addressing spiritual awareness be introduced and that these should be multi-disciplinary.

In differentiating spiritual needs from the domain of religious practices, it is necessary to identify their general nature. This makes it easier to assess them in individuals.

Preliminary work by Nathan (1997) involving patient interviews and questionnaires completed by nurses indicates that, for psychiatric patients, ‘spiritual’ needs are met by care that includes the five elements already illustrated in Box 4. Her study also identified a number of benefits of good spiritual care (Box 6).

Box 6 Benefits of spiritual care

Improved self-control, self-esteem and confidence

Recovery facilitated, both by promoting the healthy grieving of loss and through maximising personal potential

Relationships improved – with self, others and with God

A sense of meaning, resulting in renewed hope and peace of mind, enabling people to accept and live with their problems

Johnson & Culliford (2001) have produced a short guide called Healing from Within, acknowledging people's extrinsic supports (from religious organisations, for example) while suggesting that they also have intrinsic spiritual resources to draw on at critical times.

This guide, for assessing religious and spiritual aspects of people's lives, avoids specific religious terminology and is for use throughout the mental health services within one NHS trust. Murray & Zentner's (1989) definition of spirituality is reproduced and the authors offer some questions that staff may find helpful in opening up this area, recommending a gentle and unhurried approach. Asking different, non-standard questions to uncover what is going on within the experience of the patient is a recommended strategy in providing spiritual care (Reference BliseBlise, 1995).

Professional attitudes, training and the benefit of ‘spiritual skills’

Many of the components of spiritual care listed in Box 4 are already aspects of good psychiatric practice. Similarly, many of the benefits listed in Box 6 represent hoped-for outcomes of competent clinical care. This seems to indicate that no major development in thinking or philosophy of care is required. However, Greasley et al (2001) report that a personal, trusting relationship between professional and patient is necessary in addressing patients' spiritual needs, which is not achieved frequently enough. Furthermore, all patients interviewed by Nathan (1997) perceived spiritual care as an area involving all care providers.

Giving and receiving

Professional and personal development in terms of spiritual attitudes, values and skills (Box 7) can be nurtured, for example by encouraging a language of spirituality in mental health care (Reference Nolan and CrawfordNolan & Crawford, 1997) or through architecture, providing quiet spaces that are conducive to contemplative activity.

Box 7 Spiritual values and spiritual skills

Spiritual values

Kindness Compassion Generosity

Tolerance Patience Honesty

Creativity Joy Humility

Wisdom

Spiritual skills

Being able to create a still, peaceful state of mind (as in meditation)

Being able to stay mentally focused in the present, remaining alert and attentive

Developing above-average levels of empathy, discernment and courage

Having the capacity to witness and endure distress while sustaining an attitude of hope

Being self-reflective and honest with oneself, especially about areas of ignorance, also when angry, afraid or in doubt

Having an above-average level of being able to give without feeling drained

Being able to grieve appropriately and let go

Spiritual skills can be taught directly (Reference RossRoss, 1996; Reference EaggerEagger, 2001), as occurs beneficially already in education (Reference Erricker and ErrickerErricker & Erricker, 2001). Not least, they can be self-taught, both under guidance and from books (Box 8).

Box 8 Teach yourself spiritual skills and awareness – suggested reading

Dass, R. & Gorman, P. (1985) Compassion in Action. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Jung, C. G. (1933) Modern Man in Search of a Soul. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Jung, C. G. (1964) Man and His Symbols. London: Aldus Books.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994) Wherever You Go, There You Are. London: Wisdom Books.

Kornfield, J. (1995) A Path with Heart. London: Rider.

Nelson, J. (1994) Healing the Split. New York: State University of New York Press.

Kowalski, R. (2001) The Only Way Out is In. Charlbury: Jon Carpenter Publishing.

Scott Peck, M. (1990) The Road Less Travelled: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values and Spiritual Growth. London: Rider.

Thich N. H. (1993) Transformation and Healing. London: Rider.

Titmuss, C. (1999) Power of Meditation. London: Apple Press.

Whiteside, P. (2001) Happiness: The 30-Day Guide. London: Rider.

Zukav, G. (1991) The Seat of the Soul. London: Rider.

It is a principle of spiritual care that offering it benefits both parties, giver and receiver. In the medical profession, there is a high incidence of marital breakdown, drug dependency, alcoholism, depression and suicide. The data indicate that psychiatrists are especially vulnerable. Improved psychospiritual self-care by mental health professionals may help.

Nolan & Crawford (1997: p. 289) point out that those who seek to add a spiritual dimension to the care they provide must also be prepared to wrestle with their own spiritual needs. More optimistically, they add that time invested in learning about giving spiritual care can have a number of beneficial consequences for the individual, including spiritual growth, new insights, new interpretations of personal situations, a new vigour in professional practice and protection from burn-out.

Trust

The skills listed in Box 7 complement and support each other. They are useful, for example, by being among those that help professionals present themselves as honest and trustworthy and so rapidly establish lasting bonds with patients. Swinton (2001) suggests that, in the face of psychiatric illness, the quest for cure must continue, but the process of enabling healing is also a vital and immediate aspect of the daily task of caring. This bonding, and the trust that it fosters (faith in the doctor), is therefore important.

He adds that the aims and objectives of healers are to enable a person to find enough meaning in their present struggles to sustain them, even in the midst of the most unimaginable storms. He suggests that the spiritual carer has not simply to find the locus of pathology but also to discover the locus of meaning within a person's life, and in so doing, begin to explore ways in which the person's spirit can be revitalised. He draws a distinction between automatic, reflexive responses and personally intentional, meaningful actions, which are preferable. In promoting the latter, he says, it is for clinicians ‘to discern between the forms of spirituality that may be negatively affected by the person's mental health problems, and the more helpful and constructive responses of individuals to the longings of their spirits’(p. 18). In this way, the movement from reflexive existence to meaningful living can be initiated and followed through.

All this implies that mental health professionals have a duty themselves to achieve resilience, emotional stability and spiritually mature ways of living and coping. This will of necessity be a cooperative endeavour. Spirituality can be discussed with colleagues as well as with patients in non-religious, non-denominational terms; it is something to be shared rather than something potentially divisive. This discussion has already begun and is bearing fruit.

Conclusion

Spiritual authenticity involves maintaining a feeling of inspiration, thus continuing to derive a strong sense of meaning and purpose in daily life. It is an important contributor to contentment and happiness in the workplace, in recreation and in enlivening human relationships.

Spirituality is the cornerstone of the hierarchy of dimensions of human experience, as shown in Box 3. Body and mind are both influenced and united by its action, which informs and enriches the biological, psychological and inter-personal realms. The evidence supports the view, inherent in this model, that paying due attention to human spirituality will yield significant rewards in terms of healing and health at all levels.

Human beliefs are beyond scientific measurement. Their precise effects, including their benefits, are therefore unpredictable. Spiritual gains can result in partial or full transformation of the individual, serving to promote hope and the regeneration of faith in patients and carers alike. As Powell (2001) puts it, ‘When we enquire into the beliefs our patients hold, such matters deserve to be discussed with a genuinely open mind … our patients may sometimes be closer to the truth than we know.’

One way forward, taking the lead from the WHO and using Trent's (1999) two-continua model (Fig. 1), is to undertake research using both empirical and new paradigm methods along both the mental disorder axis and mental health axis. When we as psychiatrists, both individually and collectively, are much clearer about what genuinely constitutes mental health, we will be able to reach towards it more securely and with increasing skill, on behalf of our patients.

There is much to be gained (and little to be lost) in discussing this further. It might, therefore, be to the singular advantage of mental health professionals everywhere to develop – and make frequent, regular use of – a non-denominational language or ‘rhetoric’ of spirituality (Reference Nolan and CrawfordNolan & Crawford, 1997) so as to foster energetically what Swinton (2001) calls ‘the forgotten dimension’.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Spirituality:

-

a is defined by a person's religion

-

b can be thought of as a dimension of human experience

-

c cannot be investigated scientifically

-

d motivates people to search for purpose in life

-

e affects and is affected by a person's physical state, feelings, thoughts and relationships.

-

-

2. In one study, the highest number of psychiatric patients reporting benefit from spiritual belief was:

-

a 57%

-

b about 50%

-

c almost 85%

-

d 27%

-

e under 5%.

-

-

3. A holistic or spiritual approach to psychiatry:

-

a does away with the medical model

-

b acknowledges the effect of the observer on what is being assessed or examined

-

c emphasises skills and attitudes as well as knowledge

-

d requires the use of complementary therapies

-

e involves assessment of a person's level of mental health as well as of symptoms of his/ her disorder.

-

-

4. Mental health:

-

a depends on good physical health

-

b can be assumed in the absence of symptoms

-

c involves a sense of personal integrity and contentment

-

d implies continuing progress through life towards emotional resilience and personal maturity

-

e implies contentment and equanimity.

-

-

5. Patients' mental well-being is enhanced:

-

a when they are treated with dignity and respect

-

b if professional carers pay due attention to their own spiritual needs

-

c when patients are able to spend time with staff who seem sympathetic and unhurried

-

d when they have the opportunity, environment and resources for quiet reflection and for purposeful activities

-

e when they are regularly persuaded to attend religious services.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T |

| b | T | b | F | b | T | b | F | b | T |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | T | d | F | d | F | d | T | d | T |

| e | T | e | F | e | T | e | T | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.