On 6 October 2005, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that Britain's law that prevents convicted prisoners from voting violates fundamental rights protected by the 1950 European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (hereafter: the Convention).1

Hirst v. the United Kingdom (2), 74025/01, 6 October 2005.

The Sun, 7 October 2005, 1.

Hirst v. the United Kingdom, 6 October 2005, joint dissenting opinion of judges Luzius Wildhaber, Jean-Paul Costa, Peer Lorenzen, Anatoly Kovler, and Erik Jebens.

Such splits between proponents of a more “activist” and a more “restrained” role for the court are common among ECHR judges.4

This runs counter to the theoretical literature that has treated international courts as unitary actors, typically assuming that international judges seek autonomy and are motivated to make law. Governments, on the other hand, are supposed to jealously guard their sovereignty and to ensure that international judges are not overly zealous in their interpretation of treaties. Scholars differ in their estimation of who generally prevails in the resulting struggle for authority. Some argue that threats of noncompliance and exit exert a powerful constraining force on international courts.5 Others claim that although international judges are not unconstrained, they have considerable freedom in interpreting treaties and have used this to impose new obligations on states. Thus, scholars have argued that the rulings of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) have fundamentally transformed the European Union (EU) legal system,6 that decisions by the World Trade Organization's (WTO) Appellate Body have amounted to judicial policymaking,7Steinberg 2004.

Danner 2006.

This article opens the black box of judicial decision making on international courts. Using a new database of all dissents by ECHR judges between 1955 and June 2006, the analysis not only demonstrates that ECHR judges have diverse preferences but also that differences between judges are indeed about the reach of the court itself. Using the same methods employed to place U.S. Supreme Court judges along a liberal-conservative continuum, I estimate the ideal points of judges along an activism-restraint dimension. I then show that the judicial ideology of judges is linked to the political ideology of the governments that appointed them. This latter point is especially important as it suggests that there is a political logic underlying the increased activism of the ECHR. Most notably, aspiring EU members used activist judicial appointments to signal human rights commitments. Moreover, governments more favorably disposed toward European integration tended to pick activist judges.

These findings have important implications for one's understanding of the ECHR and international judicial behavior more generally. The ECHR has received little attention from political scientists9

Some notable exceptions include Moravcsik 2000 and Cichowski 2006. Neither of these articles, however, is about how the court makes decisions.

The twenty-seven EU members and Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Georgia, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Moldova, Monaco, Norway, Russia, San Marino, Serbia and Montenegro, Switzerland, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey, and Ukraine.

Second, remarkably little is known about how judges with different nationalities, from different legal cultures, and appointed by different principals resolve disputes about alleged treaty violations. To my knowledge, this is the first effort to estimate the judicial ideology of judges on any international court.13

Existing studies of judicial behavior on international courts have almost exclusively focused on bias; for example, Posner and de Figueiredo 2005.

Although this may seem self-evident, the literature on the relationship between international courts and governments has paid scant attention to the screening role of governments. More generally, the burgeoning literature that applies principal-agent theory to the relationship between governments and international organizations focuses heavily on governmental abilities to sanction poor performance as opposed to their capacity to shape international organization behavior through the appointment process.14

For an overview of principal-agent applications to international organizations, see Hawkins et al. 2006. For a critique, see Alter 2006 and forthcoming.

See Fearon 1999.

The article proceeds by briefly detailing the ECHR and the usage of activism and restraint in the ECHR's context. I then introduce plausible theoretical explanations for variations in levels of judicial activism. The empirical strategy of this article is to first estimate levels of judicial activism from observed vote choices and then regress these on measures for the various theoretical concepts. The conclusion offers some thoughts on the implications for the ECHR as well as on the generalizibility of the results to other international courts and organizations.

Activism and Restraint in the ECHR

Institutional Detail

The ECHR evaluates complaints by individuals16

The ECHR can also evaluate interstate disputes but those are rare and are beyond the scope of this article.

For a political analysis of the origins of the ECHR, see Moravcsik 2000.

See Luke Harding, “I Was Poisoned by Russians, Human Rights Judge Says,” The Guardian, 31 January 2007. Available at: 〈http://www.guardian.co.uk/russia/article/0,,2002997,00.html〉. Accessed 12 June 2007.

The ECHR's relevance increased substantially with the adoption of Protocol 11, which went into force on 1 November 1998. Previously, states were allowed to exempt themselves from compulsory jurisdiction and direct access for private litigants. France, for instance, did not accept the ECHR's compulsory jurisdiction until 1974 (when it finally ratified the Convention) and waited until 1981 to declare that French citizens could directly apply to the ECHR. Greece (1979 and 1985) and Turkey (1990 and 1987) waited even longer to accept these provisions. Protocol 11 made both private access and compulsory jurisdiction mandatory. Moreover, the Protocol implemented further institutional reforms that amongst others made the ECHR a full-time court. As a result of easier individual access and expansion of the court's membership, its caseload increased considerably: whereas the ECHR issued only seventy-two judgments in 1996, it issued 889 judgments in 2001 and 1,560 in 2006.19

All summary statistics come from the Court's annual Survey of Activities. Available at: 〈http://www.echr.coe.int〉

In the post–Protocol 11 ECHR, each application is first evaluated by the registry. About one-fourth of all applications is dismissed at this stage for administrative reasons.20

Precise proportions by year available from the Survey of Activities.

The fifth section was added in 2006. Section composition is balanced by geography, gender, and the different legal systems of member states.

ECHR judgments can demand that violating states pay “just satisfaction” to a victim and can request remedies for the violating offense. There are few credible sanctions that the Council of Europe can apply to ensure compliance, except “naming and shaming.”22

The Council of Ministers oversees the execution of judgments and publishes regular reports on compliance. Expulsion from the Council of Europe can be used as a last resort.

Especially noteworthy in this regard is the UK Human Rights Act of 1998, 2 October 2000.

Posner and Yoo 2005.

Shapiro and Stone Sweet 2002.

Blackburn and Polakiewicz 2001.

Department of Constitutional Affairs 2006.

See, for example, on the Irish case, Senan Molony, “Inmates to Vote by Post in Next Election,” Irish Independent, 23 October 2006. Available at: 〈http://www.iprt.ie/ireland/1845〉. Accessed 12 June 2007.

ECHR rulings have also been cited in domestic courts as benchmark interpretations for developing international norms. For example, a recent survey by Zaring found that ECHR rulings have been cited twenty-nine times by U.S. federal courts between 1945 and May of 2005, including four citations by the U.S. Supreme Court.30

Zaring 2006.

Ibid., 24.

Divisions on the Court

Observers commonly interpret divisions within the ECHR as concerning the size of the margin of appreciation that should be left to respondent states.32

The ECHR's margin of appreciation doctrine holds that each country has some latitude in resolving conflicts that arise between individual rights and the perceived national interests or values of that country.33Yourow 1996.

For example, the ECHR ruled in 2005 that Turkey could legitimately ban women from wearing headscarves in public education institutions.34

Leyla Sahin v. Turkey, 44774/98, 11 October 2005.

Irish Times, 22 November 2005, 10.

Dissenting opinion, Judge Tulkens, Leyla Sahin v. Turkey.

This division is generally labeled as being between those who favor “judicial activism” and those who prefer “judicial restraint.” I stick to these terms while noting their specific operationalization in the context of the ECHR: given the legal facts of a case, an activist judge is more likely to rule in favor of the applicant than a judge on the self-restraint side of the spectrum. Thus, the division is ultimately about the degree of deference a judge prefers to grant governments.

Theory: The Politics of the Appointment Process

Why, then, are some judges allegedly more activist than others? A first set of explanations focuses on the politics of the appointment process. In the post–Protocol 11 system, governments no longer have absolute control over judicial appointments. Each government submits three candidates, who they may rank order. The Council of Europe's Parliamentary Assembly then votes on the list. The assembly has occasionally selected a candidate other than the government's favorite and has refused to accept a few candidate lists for want of gender-balance or proper qualifications. Generally, however, the government's preferred candidate is elected. Judges are appointed for six-year renewable terms.

That governments screen candidates for international judicial appointments is at least plausible. Aside from human rights activists, academics, and former national judges, the list of ECHR judges includes former ambassadors, representatives to international organizations, parliamentarians, ministers of justice, and an undersecretary of state. These backgrounds may be quite informative about attitudes and vote choices of ECHR judges.37

Bruinsma 2006.

“Communists Announce Possible Recall of ECRH Judge Tudor Pantiru,” Moldova Azi, 6 April, 2001. Available at 〈http://www.azi.md/news?ID=1415〉. Accessed 12 June 2007.

For example, Bruinsma 2004 reports that each of the three final candidates for the 2004 Dutch vacancy received a personal invitation to apply.

Limbach et al. 2003, 4.

Any theory that posits a relationship between the preferences of national governments and the observed behavior of international judges needs to establish an explicit link between the desires of national politicians and heterogeneity on the court under investigation.41

See also Alter forthcoming, who argues that many existing principal-agent models of state–International Court relations are too broad to be testable due to an absence of specific assumptions about preferences.

Democracy and Domestic Human Rights Protection

Perhaps the most straightforward hypothesis is that governments that are most vulnerable to negative judgments by the ECHR seek to limit their vulnerability by exercising caution in appointing judges that are likely to be activist. Instead, governments with few concerns that the ECHR will overturn the domestic status quo may favor activist judges, who could aid them in submitting other states to a set of liberal objectives. This perspective could be labeled “realist” in that it posits that liberal states induce or coerce other states to sign human rights treaties in an effort to extend national ideals derived from national pride or geopolitical self-interest.43

See also Moravcsik 2000, tab. 1, 222.

Republican liberalism expects a more subtle relationship between domestic human rights practices and preference for an activist court. In an analysis of the ECHR's origins, Moravcsik found that governments in new democracies sought to lock-in their commitments to human rights against future political change by subscribing to the control mechanisms of the Convention.44

Moravcsik 2000.

Left-Right Politics

An obvious extension from the case of the U.S. Supreme Court, which dominates the literature on judicial behavior, is that governments appoint international judges based on their ideological orientation. Left-right conflict is pervasive in European politics, including in European supranational institutions.45

For example, Hix, Noury, and Roland 2007.

This classification may have some merit on social issues, such as cases that concern sodomy laws, gays in the military, abortion, and rights for transsexuals. There are also issues on which an activist ECHR fits comfortably within an ideological framework that should appeal to the European socioeconomic right. Several ECHR decisions have served as a check on state power vis-à-vis individual exercises of economic rights. An example is the set of Article 6 (“right to a fair trial”) cases, led by Benthem v. The Netherlands, that helped improve the ability for private persons and businesses to challenge administrative decisions, such as the rejection of permits.46

Benthem v. the Netherlands, 8848/80, 23 October 1985.

Cichowski 2006.

European Integration

An alternative thesis is that governments use judicial appointments to signal their human rights commitments to interested parties, especially the EU and its member states. The EU is a community of liberal states who view expansion as an attempt to broaden that community.48

Schimmelfennig 2001.

Kelley 2004.

European Council in Copenhagen, 21–22 June 1993, “Conclusions of the Presidency,” SN 180/1/93 REV 1, 13.

Irish Times, 11 October 1993, 8.

For a concise view of British opposition, see “Where Europe Rules,” Guardian, 11 October 1993, 19.

For aspiring EU members, appointing judges that appear willing to actively apply international standards, perhaps even against their governments, is a way to signal their commitments to a set of rules and conflict resolution procedures that are integral to the EU. As such, this argument is similar to Moravcsik's Republican Liberal thesis, except that the incentive here is signaling rather than lock-in. Judicial appointments are inadequate as lock-in mechanisms given that they are inherently short term. Yet, appointing a judge who is known to be independent or even a human rights advocate may well be an effective signaling mechanism given that it could impose short-term costs on a domestic government. Some qualitative evidence is that the CVs submitted to the parliamentary assembly for candidates from Europe's new democracies frequently stressed the independent nature of the candidate.53

See also Flauss 1998.

Among EU members there is considerable variation in how eager governments and national publics are to expand the reach of European institutions. EU membership is accompanied by ever increasing adjustments of domestic rules and regulations in response to supranational decision making and ECJ rulings.54

Some governments and national publics are more favorably disposed toward supranational commitments whereas others are more skeptical of such commitments.55 This is especially relevant as the EU currently does not include an extensive set of formal human rights commitments. This leads to the hypothesis that governments that are more favorably disposed toward the EU are also more likely to appoint activist international judges. Similarly, there are a number of non-EU members that would qualify for EU membership but have not applied. These countries, such as Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland, have traditionally been particularly cautious about making commitments to supranational institutions. As such, if preference toward supranational integration is the driving force behind the court's activism, then one would expect governments from those countries to appoint less activist judges.Theory: Domestic Legal Systems

There are reasons to be skeptical that governments appoint ECHR judges for political reasons. First, while the link between the ideologies of governments and judges seems obvious from an U.S. perspective, judicial appointments may be much less motivated by political considerations in many European countries. To the extent that research exists, there is little evidence that divisions on Europe's domestic constitutional courts are determined by partisanship.56

See Von Brünneck 1988; and Schwartz 1993, although Magalhães 1998 provides evidence for the importance of partisanship on the Portuguese Constitutional Court.

A plausible alternative is that variation in the activism of international judges stems from variation in the domestic legal systems of ECHR member states. The literature has focused mostly on the distinctions between common law and civil law countries, suggesting that many features of contemporary legal systems are inherited and thus exogenous to other aspects of the political systems of countries.57

Due to colonial exploits, military adventures, and other reasons, the legal systems of France and England have had a vast influence on systems adopted in many other countries. Divergence in these legal systems was shaped by developments in the twelfth and thirteenth century, when France moved toward adjudication by royally controlled professional judges, while England developed a system in which courts enjoyed greater independence from royal interference.58Glaeser and Shleifer 2002.

Merryman 1985 dates this back even further to the Roman judex.

Alivizatos 1995. It should be noted that much of the “new constitutional politics of Europe” has been the result of activism by judges from civil law countries, so it is thus not clear that the above characterization is even informative about judicial behavior at the domestic level (see, for example, Shapiro and Stone 1994; and Stone Sweet 2000.)

More generally, domestic legal systems vary in at least four potentially relevant ways. First, in some systems judges have greater independence from the political process than in others. Potential institutional sources of independence are lifelong tenure, which shields judges from ex post political evaluations, and the use of case law as a source of law, which increases the implications of judicial decisions.61

La Porta et al. 2004.

Third, countries vary in the extent to which national judges are used to interpret international law. In monist legal systems, domestic judges are bound to apply rules of international law whereas in dualist countries, this is so only when international law is incorporated into national legislation.62

Cassese 2005.

I thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this and the following hypotheses.

Alter 1998.

There is some ground for skepticism about these hypotheses. The view that judges who are “activist” on the national level would translate that activism to an international court relies on the notion that judicial behavior is driven by role conceptions into which judges are socialized. If judges more instrumentally determined their interests based on an assessment of the effects of their actions, one may well reach the exact opposite predictions: National judges who enjoy a high degree of independence may find that activism by an international court constitutes undesirable interference whereas judges from countries where courts are less secure from political interference may view an activist international court as a potential ally.

Estimating Levels of Activism and Restraint

The empirical strategy is first to estimate levels of judicial activism and restraint from observed dissents and then regress these on measures for the theoretical concepts introduced in the previous section. This section introduces the methodological issues, the data, and finally presents the estimated ideal points and checks these for face validity.

Method

I employ a probabilistic spatial model of judicial decision making to estimate ideal points from observed vote choices. This model has also been used to estimate ideal points of U.S. Supreme Court justices,65

legislators in the U.S. Congress,66Poole and Rosenthal 1997.

Hix, Noury, and Roland 2007.

Figure 1 illustrates the one-dimensional spatial model. Figure 1 looks at five judges who can indeed be depicted by their ideal points along a continuum from activism to restraint. Three hypothetical issues are represented by their cut-points. The probabilistic spatial model assumes that the further a judge's ideal point is to the left of an issue cut-point; the more likely that judge is to rule against the government. Conversely, the more a judge is to the right of the cut-point; the less likely it is that the judge will find a violation. There will be issues, such as issue 1, on which only the highly activist judge A is likely to find a violation (an example is the Turkish headscarf issue discussed earlier). Similarly, there will be clear violations of the Convention, such as issue 3, on which even most judges on the self-restraint side of the spectrum are likely to find a violation. The most contentious issues are like issue 2, where judges are more or less evenly split on whether an alleged violation warrants a negative judgment. Ignoring variability in the nature of cases could seriously affect estimates of judicial ideology. By the luck of the draw, some judges may vote on a disproportionate number of cases in which there were clear violations. Those judges would be labeled “activists” even if a moderate judge would have voted the same way, given the nature of the cases. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that ECHR judges vary considerably in the number of cases they voted on.

Illustration of the spatial model of judicial decision making

Unfortunately, one observes neither the judges' ideal points nor the issue cut-points. Item-response theory (IRT) can be used, however, to estimate both issue parameters and the ideal points of judges from what one does observe: whether judges ruled in favor of or against the government. IRT models were developed in the literature on educational testing, where they are used to simultaneously estimate the difficulty and discriminatory nature of test items and the ability of students from observed right and wrong answers on standardized tests. This allows evaluators to estimate standardized scores for students on tests such as the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) without requiring that all students answer the same questions. It is well understood that the probabilistic spatial model of voting is mathematically equivalent to the IRT model.69

The basic intuition is that IRT models estimate the configuration of judicial ideal points and case cut-points that are most consistent with the coalition patterns observed in the data. One has n observed responses y (vote choices), where i = 1,..,n, by J judges on K issues. yi = 1, if the vote choice is in favor of the government (that is, a finding of “no violation” by a judge), 0 otherwise. One can model these responses using a two-parameter item response model:

In this equation, θj reflects judge j's ideal point and αk represents the cut-point on issue k as outlined in Figure 1. βk is the discrimination parameter (similar to a factor loading). If βk equals 0, variation in judicial ideal points is not informative about how judges vote on issue k. If βk is large and positive, judges with positive values of θ have a high probability of voting in favor of the government. If βk is large and negative, judges with positive estimates of θ are likely to vote against the government on this particular issue. Thus, the method offers an opportunity to explicitly test whether activism-restraint is indeed the main dimension of contestation: If the main division between judges is activism-restraint, then the discrimination parameters across issues should be positive. If, left-right were the dominant cleavage, then the sign of the discrimination parameters should vary across issues, as left-wing judges are activist on some issues (for example, gay rights), but not on others (for example, property rights). Thus, one does not need to assume what the main dimension of contestation is. Instead, one can verify this by examining the discrimination parameters after estimating the model.

Data

Although there are analyses of episodes of dissenting behavior,70

See Arnold 2001; Bruinsma 2006; Bruinsma and de Blois 1997; Jackson 1997; and Schermers 1998. For legal analysis of dissenting opinions until 2000, see Rivière 2004.

Based on a search in the online catalog HUDOC, available at 〈http://www.echr.coe.int/ECHR/EN/Header/Case-Law/HUDOC/HUDOC+database〉. Accessed 12 June 2007. The search identified judgments that include the word “dissenting” in the separate opinions portion of the case. Since the full text of some cases is only included in one of the two official languages, a complementary search was performed in the French language portion of the database.

These are judgments with importance level 1 in HUDOC catalog: “Judgments which the Court considers make a significant contribution to the development, clarification or modification of its case-law, either generally or in relation to a particular State.”

I excluded votes by judges on their home countries. The spatial model assumes that judges sincerely express their ideological position when voting. One may expect judges to use a different and perhaps strategic set of motivations when they vote on cases that concern their country of origin. Whether and why this is so is the topic of a separate paper.73

Voeten 2006.

In many judgments, separate decisions were made on admissibility, the merit of violations of individual articles of the Convention, and just satisfaction (monetary compensation). Splits on just satisfaction decisions often followed naturally from decisions on the merit of the case. To the extent that they did not, judges did not always motivate why they voted differently on the just satisfaction decision than on the merit question. As such, I decided to exclude decisions on just satisfaction. Sometimes, decisions on violations of individual articles within a judgment exhibited differential patterns of disagreement between judges. For example, a government may have clearly violated Article 6 of the Convention, creating an issue such as issue 1 in Figure 1, but its alleged violation of Article 8 is much less clear and looks more like issue 2 in Figure 1. On twenty-four cases, at least half the judges expressed a dissenting opinion. Often, these were cases where some dissenters argued that no violation had occurred whereas others believed that violations of multiple articles had occurred, even though a majority could only be found on the occurrence of a subset of these violations. Treating such cases as single entries in the data set would ignore information about splits between judges. Therefore, different splits between judges were treated as separate entries in the data set.

The primary analysis contains only data on judgments that that were not unanimous. This is common in studies of judicial and legislative voting, given that unanimous votes do not provide information about variation in ideal points. Running the spatial model on unanimous votes is equivalent to running a logit model on a data set without variation in the dependent variable. One aside is that differently composed panels could have different propensities to be unanimous. Thus, unanimous votes could contain some information about ideal points.

The final data set contains votes on 709 issues with thirty-eight different respondent states. It includes ninety-seven judges who voted at least ten times, fifty-nine of whom voted at least fifty times on a contentious issue. The vast majority of issues are from recent years: 84 percent of all issues are from a judgment in 1990 or later, 54 percent of all issues come from the “new” post–Protocol 11 court. The data match the overall distribution of cases fairly well, with the notable exception that Article 6 cases (right to a fair trial) invited fewer dissents than their preponderance in the universe of judgments would suggest.74

For a more detailed analysis of the universe of cases, see Cichowski 2006.

Validity of Activism-Restraint Estimates

I estimated the models using MCMC methods within a Bayesian framework, using the robust logistic model specified by Bafumi and colleagues.75

See Bafumi et al. 2005; Pr(yi = 1) = ε0 + (1 − ε0 − ε1)logit−1βk(θj − αk), with ε0 ∼ dunif(0,.1),ε1 ∼ dunif(0,.1) θj ∼ N(μθ,σθ2), for j = 1,…, J,αk ∼ N(μk,σk2) and βk ∼ N(μβ,σβ2), for k = 1,…, K. The parameters were normalized after estimation was complete: θjadj = (θj − θ)/sθ,αkadj = (αk − θ)/sθ,βkadj = (βk) * sθ.

This is the mean of the posterior distribution of classification percentages.

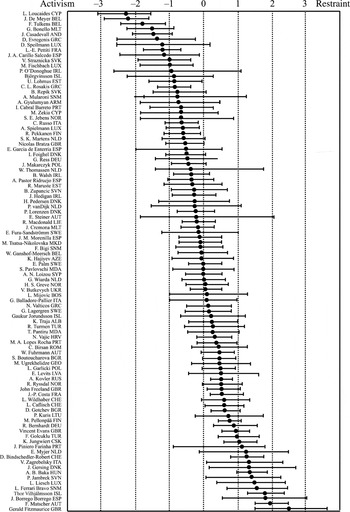

Estimates of levels of activism ECHR judges (95 percent credible intervals)

There are two ways to verify that the plotted divisions indeed reflect variation in levels of activism and restraint. First, to the extent that the positions of judges are known, the estimates have considerable face validity. The British judge Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice is estimated to be the most “extreme” judge on the restraint side. Fitzmaurice was a legal adviser in the British foreign office who became a well-known academic and a judge on the International Court of Justice (1960–1973) before coming to the ECHR in 1973. He is often cited as the prototype of the “tough conservative” judge,77

Merills 1988.

Bruinsma and Parmentier 2003.

Matscher 1993, 70.

Ibid.

Similar observations can be made about many of the judges with estimated ideal points on the activist side of the spectrum. The Belgian judge Françoise Tulkens (the lone dissenter on the Turkish headscarf case) asserted in a recent interview that: “One can speak of judges who are concerned about problems of the raison d'état and others who sympathize with the applicants. The raison d'état is more present here than I would have thought possible.”81

Bruinsma 2006, 211.

Ibid., 225.

Jackson 1997, 25.

Bruinsma 2006.

A second verification mechanism is the examination of the discrimination parameters. All votes were coded as 1 if they were decisions in favor of the government and 0 if they went against the government. If activism-restraint is the main dimension of contestation, then one would expect a positive relationship between the ideal points of judges and their propensity to vote in favor of the government. As such, one would expect the discrimination parameters to be positive. If the main dimension of contestation reflected some other meaning, there is no a priori expectation of such a positive relationship. For example, if it reflected left-right conflict, one may well expect that judges on the right have a tendency to vote against governments on property rights issues but not on abortion or gay rights. There are no issues on which the 90 percent credible interval of the discrimination parameter falls below 0. Thus, one can comfortably assert that the main dimension indeed reflects activism-restraint.

Why Are Some Judges More Activist Than Others?

Why are some judges more activist than others? This section seeks to answer this question by regressing indicators derived from the various theoretical perspectives on the estimates of judicial activism introduced in the preceding section. Given that the theories are not mutually exclusive, they are evaluated in multiple regression analyses. The dependent variable is the mean of the posterior distributions for each judge, as depicted in Figure 2. Higher scores indicate more restrained judges and lower scores more activist judges. I use weighted least squares to adjust for the variation in precision of the ideal point estimates.86

The weight is 1 divided by the standard deviation of the posterior.

Note that given the small number of votes before the 1980s, most of the early judges were dropped from the sample because they had not participated in at least ten controversial votes.

Weighted least squares regressions on levels of activism

Trends in Levels of Activism

A key observation that motivates this article and much of the literature on international courts is the perception that international courts tend to become more activist as time progresses. Early on in the life of a court, judges may be hesitant in their activism as they are uncertain as to the implementation of the court's decisions as well as the institutional future of the court itself. Judges that enter into a more mature court may well perceive an increased sense of institutional security of the court and hence feel more liberated to make decisions that may be perceived as unpopular by governments. To capture this effect, each model includes a linear time counter. This time counter is negative and significant in virtually all specifications.

Figure 3 plots the mean ideal point estimate for ECHR judges from 1978 to 2006.88

1978 was chosen as it was the first year with at least twenty judges in the data set.

For example, Mowbray 2005.

Cichowski 2006.

Note that we can anchor the space because there generally is considerable continuity in the composition of the bench, even in 1998.

Temporal change in mean activism of ECHR judges

Democracy and Domestic Human Rights Protection

Do governments that offer better protections for individual rights generally appoint judges that are more activist than governments that provide less broad guarantees to their citizens? The main indicator for domestic rights protection is a country's Freedom House civil liberties score at the time of a judge's election, running from 1 (extensive civil liberties) to 7 (very restrictive civil liberties).93

See 〈www.freedomhouse.org〉. Accessed 12 June 2007.

Taken from Mark Gibney, at 〈http://www.unca.edu/politicalscience/images/Colloquium/faculty-staff/gibney.html〉. Accessed 12 June 2007.

Results available upon request from author.

The ECHR also aims to correct deficiencies in the functioning of domestic legal systems. Hence, it may be that countries with legal systems that are generally perceived to function poorly are less likely to pick activist judges. I therefore also included a six-point “law and order” scale developed by the Inter Country Risk Guide published by Political Risk Services.96

See 〈http://www.prsgroup.com/ICRG.aspx〉. Accessed 12 June 2007. Data is available from 1980 onwards.

In short, there is no evidence that countries that appear vulnerable to an activist ECHR tend to pick judges that favor self-restraint. One reason for this finding may be that there is too little variation: countries that are willing to commit to the ECHR's jurisdiction generally have high levels of domestic rights protection. Most judges come from countries with either a Freedom House score of 1 (54 percent) or 2 (26 percent). On the other hand, even casual inspection of Figure 2 shows that the most self-restraint judges are generally not from the remaining poor performers but rather from countries that have strong records in protecting human rights, such as Iceland, Austria, and the United Kingdom.

Moravcsik posits a more sophisticated relationship between democracy and preferences for binding international human rights courts.97

Moravcsik 2000.

Reasonable extrapolations were made to democracies (for example, Luxembourg) that Polity did not cover.

Left-Right Politics

Are judges appointed by left-wing governments more activist than judges appointed by right-wing governments? It is difficult to adequately measure the ideological composition of governments in a comparative way. The most straightforward approach is based on party families. A measure for left-wing government ideology is the percentage of total cabinet seats, weighted by days of a calendar year, held by social-democratic and other left parties.99

Armingeon et al. 2005. The data for Eastern European countries is computed from Armingeon and Careja 2004. Missing information is imputed from Beck et al. 2001.

The results show that this indicator has the predicted effect. A government composed of only left-wing parties is estimated to appoint a judge who is around .40 points more activist than a government composed of only parties of the right. This effect is substantively important: it represents a shift of almost half a standard deviation in the distribution of judges. Yet, the standard error on the coefficient is large. It is not implausible that left-right divisions matter because left-right correlates (imperfectly) with preferences for international integration in general, and EU integration in particular. More on that in the next section.

European Integration

Do governments use judicial appointments to signal their human rights commitments to interested parties, especially the EU and its member states? I code aspirant membership with a dummy variable that takes the value 1 after a government has announced its intentions to join the EU and there have been at least some formal discussions with the EU with regard to a country's membership.100

In the absence of a clear announcement date, I coded a country as aspiring in the ten years leading up to their EU membership.

Aside from the variables in Table 1, I have also assessed its robustness to the inclusion of GDP per capita.

The second hypothesis regarding European integration is that governments more favorably disposed toward integration are more likely to appoint activist judges. I created a measure for government preferences toward the EU using data from expert surveys from twenty-five of the twenty-seven current EU members, including Bulgaria and Romania.102

Expert survey data come from Ray 1999; Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson 2002; and Marks et al. 2006. The expert survey data is available from 〈http://www.unc.edu/∼gwmarks/data.htm〉. Accessed 12 June 2007.

The results in Model 2 show strong support for the hypothesis that government support for European integration is an important driving force behind judicial ideologies. A government fully on the anti-European integration side of the scale is expected to appoint a judge about 1.6 points further to the self-restraint side of the scale than a government on the pro-integration side. The standard deviation of the dependent variable is .90, so this is a sizeable effect. In short, governments less favorably disposed toward European integration also appoint judges who are less favorably disposed toward extending the reach of a European supranational court. Thus, there is a demonstrable political logic behind the appointment process.

It should be noted that governmental preferences toward European integration could only be determined for slightly more than half the sample. I estimated a similar model with an alternative measure of governmental preferences toward the EU, based on party manifesto data.104

This measure took the percentage of positive minus negative statements on EU integration for parties. Data are from Armingeon et al. 2005.

Where coefficient −0.165, significant at 10 percent level, only thirty-three cases.

Domestic Legal Systems

Are international judges from civil law countries, where judges have traditionally played a subordinate role, less likely to be activist than judges from common law countries? The results from Table 1 show no evidence for this proposition.106

Data on legal origins are from La Porta et al. 1998.

p = 0.141.

To further scrutinize the potential impact of domestic legal systems, I estimated models that code institutional protections for judicial independence as well as the presence of constitutional review in countries.108

La Porta et al. 2004.

There is also no evidence that judges from countries that have been in the EU for a longer period, and thus, presumably, are more accustomed to an activist international court, are more activist (although the coefficient in Model 1 has the predicted sign). Finally, Model 3 tests whether judges from monist countries were more activist than judges from dualist countries. Unfortunately, this data is also only available for a subsample.109

Voigt 2006.

In sum, then, these analyses do not provide evidence for the thesis that judges transport their supposed domestic roles into the international arena.

Conclusions

A first conclusion from this study is that “activism–self-restraint” constitutes the most prominent divisions between ECHR justices. That is, judges vary in the extent to which they show deference to governments when assessing whether a violation has occurred. That this dimension rather than a more value-based cleavage emerges as the most prominent dimension is telling, and points to an interesting difference with the U.S. Supreme Court. It means, among others, that conflict over the proper reach of the institution is at the heart of divisions between judges. It also suggests that the common assumption that international judges share an interest in the expansion of the reach of their court is unwarranted. This assumption is fundamental in current theoretical explanations for the agency of international courts.

Second, the analysis implies that politics plays a role in international judicial appointments, as it does nationally (at least in the United States). Governments are heterogeneous in their preferred levels of activism of international courts and this warrants attention in one's conceptualizations of the interactions between governments and courts. As such, the results challenge the assumptions underlying both the trustee model,110

See Alter 2006 and forthcoming.

Third, the results suggest that governments, at least to some extent, use judicial appointments to fill the ECHR with agents that match their preferences. There are reasons to suspect that such screening also occurs on other international courts. Steinberg reports, for instance, that both the EU and the U.S. Trade Representative conduct extensive interviews with candidates for the WTO's appellate body, with an explicit focus on the degree to which the candidate can be expected to have an expansive view of judicial decision making.112

Steinberg 2004.

Costa 2003, 744.

Alter interviewed legal scholars and government officials in France, Germany, and the UK, as well as the Italian, Greek, Dutch, Belgian, French, German, British, and Irish judges at the ECJ; see Alter 1998, 139, fn. 62.

Unfortunately, it will be difficult to verify these assertions using the methods developed here. Dissents on other international courts are either shrouded in secrecy (WTO or ECJ) or are too limited in number to allow the type of statistical inquiry engaged in here (International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunals).116

For a statistical analysis of ICJ votes that answers a different set of questions, see Posner and de Figueiredo 2005.

Fearon 1999.

Studying judicial selection in the absence of public dissenting opinions may still be possible. ECHR judges whose previous careers were primarily as diplomats or bureaucrats are significantly less activist than are judges with other previous career tracks.118

Mean activism score for diplomats and bureaucrats was 0.35 (N=24), for others −0.11 (N=73). P-value is 0.029.

Finally, the analysis reveals that the ECHR's composition has grown more activist over time as governments have tended to replace more restrained judges with more activist judges. The evidence suggests that this process is driven in good measure by European integration. Governments more favorably disposed toward European integration tend to appoint more activist judges. Aspiring EU members appoint more activist judges than other nonmembers. Neither of these findings disappears when controlling for the most obvious alternative accounts. If this finding survives further scrutiny, it suggests rather strongly that the EU has been the driving force behind the increased activism of the ECHR, even if there is little formal relationship between the EU and the ECHR. This spillover effect of the EU into the role of supranational institutions elsewhere in Europe warrants further attention. I have suggested that the Protocol 11 reform was driven by the issue of European integration but further qualitative evidence could be collected to test that hypothesis more systematically. Nevertheless, from the results presented in this article, it appears that the increased activism of the ECHR has a political logic and is not merely the result of “wayward judicial activism,” as Margaret Thatcher labeled the ECHR decision that overturned the British prohibition for gays to serve in the military.119

The Scotsman, 24 March 2002, 2.