1. Introduction

This article discusses the three distinct matters at issue in the appeal in EU–PET (Pakistan),Footnote 1 namely (i) the need for findings in respect of measures that expired after Panel establishment; (ii) the conditions under which duty drawback schemes may constitute subsidies and the calculation of the subsidy amount; and (iii) the causation methodology to apply under the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement).

Although the question of findings (and recommendations) in respect of expired measures continues to lead to disagreements between WTO Members, the Appellate Body has yet to clarify whether the design and function of the WTO dispute settlement system require or preclude findings on expired measures. This article explains why the analysis of the Appellate Body in EU–PET (Pakistan) did not definitively resolve this matter. By contrast, the report usefully clarifies, in respect of duty drawback schemes, that the investigating authority may consider as a subsidy only the remission paid in excess of the amounts due. Finally, despite the Appellate Body's conclusion that any methodology for the causation analysis should be permissible as long as it results in a complete and objective analysis, it appears that the methodology used by the investigating authority in this case showed a number of deficiencies that were raised by Pakistan but not recognized by the Appellate Body. In particular, by not going beyond a determination that the impact of each individual other factor is limited relative to the investigated imports, the European Commission (Commission) did not properly separate and distinguish the attenuating effect of other factors, in line with Pakistan's claims. Furthermore, an unusual feature of this investigation was the fact that the only negative trend among the factors determining the state of the domestic industry was the domestic market share. Negative market share being the key factor in determining injury makes the whole causation analysis a mechanical exercise, demonstrating that a positive trend in imports caused a negative trend in domestic market share.

After setting out, in Section 2, background information on the countervailing investigation and its economic impact on Pakistan's exports and a summary of the main issues considered at the Panel stage, this article discusses each of three points raised on appeal, namely the need for findings on expired measures (Section 3), duty drawback schemes (Section 4), and an economic review of the findings on causation (Section 5).

2. Background

2.1 The EU Countervailing Investigation

In 2009, the European Union initiated a countervailing investigation regarding imports of polyethylene terephthalate (‘PET’ or ‘polyester’) from Pakistan. PET is a widespread plastic for packaging of consumer goods used for everyday products such as prepared foods, bottles, liquid soaps and shampoos, photographic and video films. About half of the synthetic fiber in the world is made from PET fabric (PET Resin Association, 2015).

The Commission investigated, among others, Pakistan's ‘Manufacturing Bond Scheme’ or ‘MBS’ and found it to constitute a countervailable subsidy contingent in law upon export performance which had caused material injury to the European Union (EU) industry. That scheme enables materials to be imported duty free into Pakistan on the condition that the materials would then be used as an input in the manufacture of goods that were subsequently exported. Novatex, Pakistan's only PET producer (Mubashir, Reference Mubashir2012), had used the MBS scheme. However, as a result of a lacking verification system, it was unclear which and/or how many inputs were used for subsequently exported products.

According to the Commission, the MBS was an impermissible duty drawback system because there were failures or malfunctions in Pakistan's verification system. It took the view that, when there is no permitted drawback system, the benefit conferred is the remission of total import duties normally due upon importation of inputs. Furthermore, the amount of revenue forgone in the form of all the unpaid duties was countervailable, given that the exception for drawback schemes under EU law was not applicable. In examining the causal link between subsidized PET imports and material injury, the Commission found that none of the other factors examined contributed to that injury in a manner that would break that causal link.

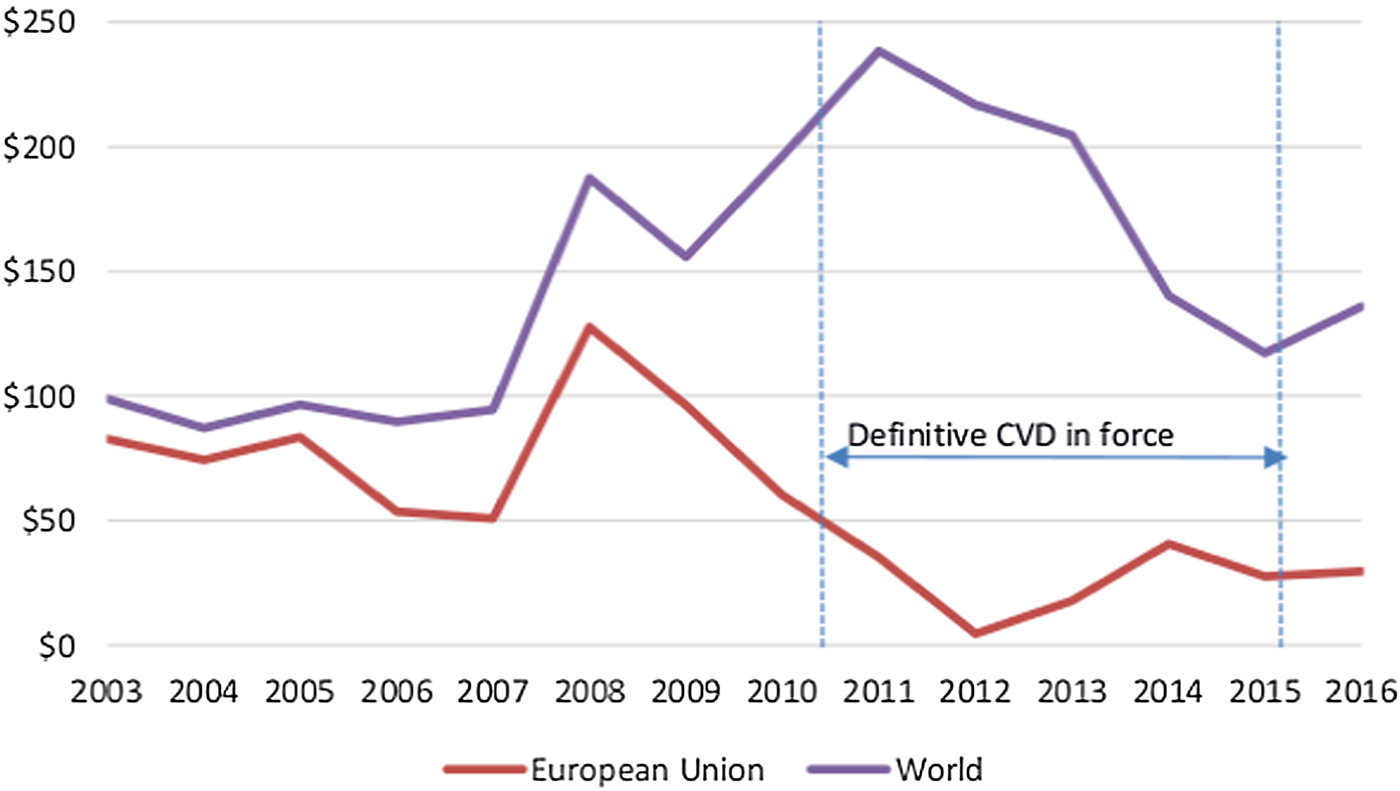

Figure 1 shows relevant export trends. Pakistan exported about $100 million during the period of 2003–2007. Until the investigation, the European Union was the main destination of Pakistan‘s nascent PET exports: the European Union‘s share in Pakistan‘s exports was over 80% until 2005, falling to about 60% in 2006–2008. Bilateral exports to the European Union peaked in 2008, the year before the initiation of the countervailing investigation, at $128 million. This value of bilateral trade puts the dispute above median but below the mean in a sample of WTO disputes between 1995 and 2011 (Bown and Reynolds, Reference CP and KM2014).

Figure 1. Pakistan's exports, by destination (in USD million)

As seen from Figure 1, the countervailing investigation in 2009 and resulting duties in 2010 coincided with a drastic fall in exports to the European Union from about $100 million in 2009 to close to zero in 2012 before showing some recovery from 2013. However, even after the expiry of the measures in 2015, the exports to the European Union remained significantly below the levels prior to their introduction.

Although the impact of countervailing measures that came into force in 2010 had an immediate impact on Pakistan's exports of PET to the European Union, Pakistan filed a request for consultations in 2014. This might be explained by the fall in world exports of PET from Pakistan in 2014. Its world exports grew rapidly from 2008 onwards, reaching a value of approximately $240 million in 2011.

The question of extensive import protection of domestic PET producers and associate market price impact was raised by the investigated parties during the investigation.Footnote 2 Imports of PET have been subject to a number of EU antidumping and countervailing investigations and definitive measures. Overall 13 exporting countries of PET to the European Union have been subjected to an investigation between 1999 and 2011. In three instances (in 1999, 2009, and 2011) antidumping and countervailing investigations were initiated simultaneously against the same exporters. At the time of the initiation of the countervailing investigation, antidumping against eight countries were in force (India, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand, Taiwan, China, and Australia); for three of them (Malaysia, India, and Thailand) countervailing measures were also being applied. The Commission countered that the rapid increase in PET demand in the 1990s resulted in excessive investment and global oversupply. This could be related to the market structure of the PET industry: polymer producers such as PET have upstream plants with large plant-level returns to scale (Habib, Reference Habib2014).

2.2 The Panel Stage

On 25 March 2015, a Panel was established to consider Pakistan's complaint regarding the European Union's provisional and definitive countervailing duties on imports of certain PET from Pakistan,Footnote 3 as well as certain aspects of the underlying investigation and determinations. The Panel was composed on 13 May 2015.Footnote 4

On 30 September 2015, the countervailing measures expired. That expiry was announced by the publication of a Notice which explained that no substantiated request for review of the countervailing duties on PET imports from, inter alia, Pakistan had been filed.Footnote 5 On 1 October 2015, the European Union informed the Panel of the expiry and invited the Panel to terminate its work on the dispute. On 15 October 2015, Pakistan asked the Panel to continue its work. Pakistan sought, and obtained from the Panel, findings. However, it did not request recommendations regarding the expired measures. Pakistan took the view that Article 19.1 DSU does not authorize Panels to make recommendations on expired measures.Footnote 6

Next, the European Union requested a preliminary ruling on the matter. That request was denied. The Panel rejected all of the challenges under Article 6.2 of the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU). It also denied the request that the Panel cease all work regarding the dispute, given that the measure at issue had expired.

On the merits of Pakistan's claims with respect to the MBS, the Panel agreed that the Commission had failed to provide a reasoned and adequate explanation for why the entire amount of remitted duties was ‘in excess of those which have accrued’ within the meaning of footnote 1 of the SCM Agreement.

A separate category of claims related to causation under Article 15.5 of the SCM Agreement. That provision requires that it be ‘demonstrated that the subsidized imports are, through the effects of subsidies, causing injury within the meaning of [the SCM Agreement]’. The Panel found that Pakistan had failed to establish that the European Union had acted inconsistently with Article 15.5 by: (i) using the so-called ‘break the causal link’ methodology and (ii) failing to conduct a proper non-attribution analysis of the economic downturn and of imports from Korea. At the same time, the Panel agreed with Pakistan that the analysis of competition from non-cooperating producers and of oil prices was contrary to Article 15.5.

Both parties appealed against the report. The three issues on appeal related to: (i) the decision to make findings on claims regarding expired measures; (ii) the finding on the excess remissions principle; and (iii) the finding that Pakistan had not established that the ‘break the causal link’ approach is inconsistent with Article 15.5.

3. Findings on Expired Measures

3.1 The Distinction between Findings and Recommendations

By acceding to the WTO, WTO Members have accepted the jurisdiction of Panels and the Appellate Body to decide on any dispute regarding the interpretation and application of the WTO covered agreements and the competence of the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) to adopt their reports by reverse consensus. As a result of that rule, no defendant may block the establishment of a Panel and the adoption of a report. Thus, for an individual dispute, there is no need for the parties to that dispute to consent to the jurisdiction of Panels and the Appellate Body. That compulsory jurisdiction is also a contentious jurisdiction and therefore the existence of a dispute is essential. It is common ground that there is no legal basis in the DSU for advisory jurisdiction.

If there is a dispute falling within a Panel's terms of reference, in principle it must make findings and recommendations. The distinction between findings and recommendations, made throughout the DSU, is that only the latter are considered to trigger the availability of remedies under Articles 21 and 22 of the DSU. Pursuant to Article 19.1 of the DSU, ‘[w]here a panel or the Appellate Body concludes that a measure is inconsistent with a covered agreement, it shall recommend that the Member concerned bring the measure into conformity with that agreement’. In essence, a finding concerns the measure existing at the time of Panel establishment; a recommendation ‘is prospective in nature in the sense that it has an effect on, or consequences for, a WTO Member's implementation obligations that arise after the adoption of a Panel and/or Appellate Body report by the DSB’.Footnote 7 The common understanding is that implementation obligations are triggered by recommendations adopted by the DSB, although Article 21 of the DSU in fact concerns the implementation of recommendations and rulings.Footnote 8 Although a recommendation presupposes a finding of inconsistency (the Member concerned must take corrective action to remove the violation), the case law shows that, in case of expired measures, a finding may be made (or requested) without a recommendation.

The expiry of a measure may have various causes. A defendant might, inter alia, change policy, recognize the WTO-inconsistency of the measure, or consider that the underlying circumstances justifying the measure are no longer present without taking a position on its WTO-inconsistency. Thus, the expiry of a measure does not necessarily entail a concession of the defendant that its measure was contrary to WTO law. In fact, the mere fact of the expiry of a measure is neutral as to a respondent's position on the legality of the expired measure and arguably also in relation to the possibility of re-introducing the measure (for example, as a result of a new investigation).

Against that background, the question arises: what are Panels to decide if they find that the measures at issue have, following Panel establishment, expired, been withdrawn or repealed?

3.2 Findings and Recommendations Regarding Expired Measures

In EU–PET (Pakistan), it was not contested that the measure at issue were in force at the time of Panel establishment. The uniqueness of this case lies in the fact that Pakistan requested findings but not recommendations. As a result of the expiry of the measure after Panel establishment, the parties disagreed on whether there was still a dispute of which the resolution required findings to be adopted (eventually) by the DSB. This case therefore invited the Panel and eventually the Appellate Body to address whether the WTO dispute resolution might lose its purpose in case of an expired measure, and, if so, under what circumstances.

In general, the case law suggests that WTO Members continue to disagree on whether Panels may make findings and/or recommendations regarding expired measures.

One position, defended by the European Union in EU–PET (Pakistan), is that measures expiring subsequent to Panel establishment fall within Panels’ jurisdiction, but Panels should decline to exercise that jurisdiction. According to the European Union, where the measure at issue has expired, a positive solution to the dispute within the meaning of Article 3.7 DSU is achieved and there is no longer any need for findings and recommendations.

According to another, Panels may make findings but not recommendations. That appeared to be the position of the Appellate Body in US–Certain EC Products, finding that the Panel had ‘erred in recommending that the DSB request the United States to bring into conformity with its WTO obligations a measure which the Panel has found no longer exists’ (paras. 81 and 129).Footnote 9 The Appellate Body clarified its position in US–Upland Cotton as meaning that ‘the fact that a measure has expired may affect what recommendation a Panel may make … [but it] is not, however, dispositive of the preliminary question of whether a Panel can address claims in respect of that measure’ (para. 272).Footnote 10 Building on that clarification, the Appellate Body in China–Raw Materials created an opening for formulating recommendations regarding expired measures. The Appellate Body recognized that ‘[t]he DSU does not specifically address whether a WTO Panel may or may not make findings and recommendations with respect to a measure that expires or is repealed during the course of the Panel proceedings’ (para. 263). On the one hand, it accepted that the resolution of a dispute regarding a law or regulation that has been repealed does not require a recommendation (para. 264). On the other, it found that a recommendation is required in case of a claim against ‘a group or “series of measures” comprised of basic framework legislation and implementing regulations, which have not expired, and specific measures imposing export duty rates or export quota amounts for particular products on an annual or time-bound basis’ (para. 264). In EU–Fatty Alcohols (Indonesia), the Appellate Body stated the rule according to which ‘where a measure has expired, a Panel is not precluded from making a recommendation on such a measure’ (para. 5.201).Footnote 11

A variation of the second position is that a Panel must make findings on expired measures properly within its terms of reference but may not make such findings if that would result in delivering an advisory opinion.Footnote 12

A third position is that Panels must make both findings and recommendations regarding expired measures. According to that position, it is not for a complainant to waive the right to a recommendation. Where a complainant does so, it effectively means that a Panel proceeding becomes advisory.Footnote 13

Finally, it has been found that, in circumstances where the measure has expired or there is uncertainty regarding the existence of the measure, a finding together with a qualified (or conditional) recommendation might be appropriate.Footnote 14

3.3 The Position of the Appellate Body in EU–PET (Pakistan)

Regardless of those different positions, the starting point is that a measure falling within a Panel's terms of reference must be a measure that exists at the time of Panel establishment.Footnote 15 In EU–PET (Pakistan), the Panel made findings relating to measures that uncontestably had expired after Panel establishment. There was also no doubt that, at the time of Panel establishment, a dispute existed. As a result of the expiry of the measures, the Appellate Body was asked whether the Panel had objectively assessed, in accordance with Article 11 of the DSU, that there was still a dispute requiring a determination by the Panel.

The Appellate Body confirmed that Panels enjoy discretion, as part of their inherent powers in exercising the judicial function, to decide whether there is a dispute. It then focused on the conditions under which that discretion may be exercised (paras. 5.16 and 5.17). In EU–Fatty Alcohols (Indonesia), the Appellate Body had already taken the position that a Panel enjoys discretion to decide on the effect of modifications to, or the expiry of, or repeal of the measure at issue. The expiry of a measure does not necessarily mean that a Panel may not address claims with respect to that measure (paras. 5.27 and 5.180). In EU–PET (Pakistan), the Appellate Body added that a Panel's inherent powers include ‘the authority of a Panel to assess objectively whether the “matter” before it … has been fully resolved or still requires to be examined following the expiry of the measures at issue’ (para. 5.19).

The Appellate Body found that accepting that the mere expiry of a measure results in a Panel declining the exercise its jurisdiction (and thus refusing to make findings) would mean that defendants could shield their measures from scrutiny by a Panel (para. 5.39)

In essence, the position of the Panel and the Appellate Body is that, in the absence of clear evidence of a satisfactory settlement of the matter (Article 3.4) or a positive resolution to the dispute (Article 3.7), the presumption is that the expiry of the measure after Panel establishment means that there continues to be a disagreement between the parties regarding the interpretation and application of the WTO covered agreements.

That position is primarily aimed at preserving the compulsory jurisdiction of WTO dispute settlement. Should the expiry of a measure following Panel establishment automatically mean that there would no longer be a basis for exercising jurisdiction, that would enable a defendant to deprive a complainant of its right to obtain a finding. It would confer on defendants a powerful tool for selecting the disputes that are eventually heard. At the same time, a complainant might need to resort multiple times to dispute resolution in order to address in essence the same ‘problem’, rendering the use of WTO dispute settlement less efficient and more costly. Furthermore, as a matter of game theory, the dispute settlement system risks becoming dysfunctional in case no findings are to be made in relation to measures expired after Panel establishment. Applying backward induction in a game-theoretic context suggests that exporting countries would not initiate a costly dispute if they knew that no decision would be made regarding a measure currently in force but scheduled to expire before the circulation of a Panel report. In turn, importing countries would impose WTO-inconsistent measures set to expire before that time as they would correctly anticipate that the exporting country would in fact not initiate a dispute.

The fact that Pakistan continued to request findings was, according to the Appellate Body, not the sole dispositive factor on which the Panel had relied. The Appellate Body nonetheless accepted that this was a relevant factor given the rights under Articles 3.3 and 3.7 of the DSU (para. 5.42). Thus, considerable deference was given to a complainant in deciding that a dispute remains because Article 3.3 of the DSU states that a dispute arises when a Member considers that benefits accruing to it are being impaired by measures taken by another Member.Footnote 16 Likewise, under Article 3.7 of the DSU, the presumption is that a WTO Member submits a request for Panel establishment in good faith and following an assessment as to whether such a request would be fruitful.Footnote 17

If there is a measure with respect to which there is (still) a ‘problem’, then the WTO dispute settlement system functions as a means to finding a positive solution for that problem. In light of that position, the Appellate Body in EU–PET (Pakistan) refuted the European Union's argument that there is no nullification or impairment to quantify in case of expired measures. According to the Appellate Body, ‘demonstrating nullification or impairment is not a prerequisite for bringing a dispute under the DSU’; infringement of an obligation merely creates a rebuttable presumption of nullification or impairment (para. 5.30). The fact that there might not be any cause for retaliation also failed to convince the Appellate Body, given that the purpose of WTO dispute settlement is to find a positive solution and retaliation is only a means of last resort.

Therefore, as long as a measure continues to produce some effects, there is still a problem requiring resolution. Such effects, including the fact that the measure is still subject to some government action, can affect imports.Footnote 18 A common example is where duties have been withdrawn (possibly because of a WTO-inconsistency) and refund applications are available before national courts. For that reason, certain Panels have formulated so-called ‘conditional’ recommendations. Conditions in recommendations regarding expired measures include ‘to the extent that those schemes continue to be operational’, ‘if, and to the extent that, that measure has not already ceased to exist’, ‘to the extent that they continue to have effects’, ‘to the extent that there may continue to be effects with respect to imports occurred when the measure was in force’, or ‘if, and to the extent that, the said modifications to the tax stamp have not already done so’.Footnote 19

In essence, whether a measure has expired and/or continues to produce effects or may be re-introduced is a matter of evidence. Therefore, the question of the need to make findings may be managed through the question of whether a complaining party has satisfied that burden of proof. So far, the case law suggests that that burden of proof might not be particularly hard to satisfy. That can be explained, in part, by the fact that Panels might be reluctant to make their findings (and recommendations) dependent on a detailed assessment of the availability of remedies under national law and the extent to which findings in a DSB report may assist in obtaining those remedies. In all of these circumstances, if it is established that the measure might continue to produce effects, then the dispute arguably has not entirely disappeared. In such circumstances, findings and recommendations are required. Whether the continued effects result in action covered by a defendant's implementation obligations may subsequently be determined by means of the definition of the jurisdiction of an Article 21.5 Panel.

However, in EU–PET (Pakistan), both the Panel and the Appellate Body (implicitly) considered that such option was not available given that Pakistan had not requested recommendations. Nor had Pakistan sought to satisfy its burden of showing continued effects of the measures at issue (for example, by offering some evidence of the availability of refund applications). As a result, the Panel and the Appellate Body did not examine of their own motion, given their inherent jurisdiction and after having heard the parties, whether the measure continued to produce effects and whether, on that basis, findings (and possibly recommendations) were required. They also failed to examine whether, despite the absence of a request for recommendations, Article 19.1 DSU required the formulation of a recommendation if findings of WTO-inconsistency are made.

Instead, the Appellate Body considered different readings of the Panel's consideration that there was a reasonable possibility that the European Union could impose CVDs on Pakistani goods in a manner that may give rise to certain of the same, or materially similar, WTO inconsistencies. If the Panel ‘considered it a “reasonable possibility” that the European Union could re-impose the very same measure that had expired and had ceased to have legal effect’, the Appellate Body agreed with the European Union that this would require the initiation of a new investigation covering a different investigation period (para. 5.47). However, the Appellate Body understood the Panel to express its concern ‘with the correct interpretation of the relevant provisions of the SCM Agreement and the GATT 1994, and the conformity, with this correct interpretation, of the Commission's reasoning and findings underpinning the now expired measure’ (para. 5.48). The Appellate Body agreed that therefore there was still a dispute between the parties which was not fully resolved as a result of the expiry of the measure (paras. 5.48 and 5.49). This part of the report caused one Appellate Body Member to propose a stricter review of the analysis of the risk of re-introduction which was, according to that Member, the essential basis for the Panel's findings. He criticized the Panel for summarily dismissing the argument that there was no reasonable possibility for the European Union to affect Pakistan's imports of PET in the near future on issues involving the same or similar WTO inconsistencies that were alleged in the present dispute (paras. 5.57 and 5.58).

In the absence of clear evidence of the future re-introduction of the measures, the ‘risk’ of re-introduction is an uncertain basis for exercising jurisdiction and should not easily be assumed. As the Panel in Argentina–Textiles underscored, the assumption is ‘that WTO Members will perform their treaty obligations in good faith, as they are required to do by the WTO Agreement and by international law’ and therefore ‘in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary’, it cannot be assumed that a WTO Member will first withdraw the measure and then reintroduce it in an attempt to evade a Panel's consideration of its measures (para. 6.14).

However, if, as the Appellate Body's reasoning suggests, in EU–PET (Pakistan), the measure had ceased to exist, there were no lingering effects and there was no risk of re-introduction of the measures (because a new investigation would have been required), then upholding the findings could have been based on the principle that, for the purposes of making findings, it is sufficient that the measure exists at the time of Panel establishment. If that is the controlling principle, it would have been preferable that the Appellate Body expressly recognized that principle, and explained its consequences in light of the wording of Article 19.1 of the DSU. The risk of re-introduction might be suitable in case of measures that form part of a chain of recurrent measures subject to continuing renewal. However, in most circumstances, relying on that risk might very well correspond to an easy but uncertain proxy for deciding that discretion is to be exercised so as to result in findings.

The Appellate Body also refuted the European Union's position that Pakistan was, in effect, seeking an advisory opinion on the ground that ‘the Panel's legal interpretations and reasoning were made in the context of addressing Pakistan's claims that specifically challenged a measure that was in existence at the time that the DSB established the Panel and set out its terms of reference’ (para. 5.32). The Appellate Body recalled that, pursuant to Article 3.3,Footnote 20 Members initiating a dispute are entitled to a ruling by a WTO Panel and that that provision did not exclude expired measures from its scope (paras. 5.24 and 5.26). Thus, in that part of its report, the Appellate Body recognized that the controlling principle is the existence of a measure at the time of Panel establishment. However, if that is the case, arguably there was no need to refer to the risk of re-introduction.

The reasoning in EU–PET (Pakistan) has nonetheless exposed the Appellate Body to the criticism that it issued an advisory opinion.Footnote 21 According to the United States, the mere fact that Pakistan had not requested recommendations confirmed that there was no dispute between the parties. However, at the time of the appeal in EU–PET (Pakistan) and the adoption of the Appellate Body report, the United States took the view that the Panel was correct to make findings regarding the expired measures taking into account that the measures existed at the time of Panel establishment. It also considered that a recommendation is required in such circumstances.Footnote 22 Given its objections and despite the fact that it recognized that both parties ‘agreed that the absence of any recommendation by the DSB would help them reach a positive solution’, the United States declared at the DSB meeting that it ‘did not consider those alleged ‘findings’ to be adopted by the DSB at the present meeting’.Footnote 23 Thus, although both the United States and the European Union relied on the need to avoid exercising advisory jurisdiction, they did so on different grounds.

Overall, there is a need for certainty and clarity regarding the availability of findings and recommendations in respect of expired measures. The Appellate Body refused to state that the controlling principle is that, provided a measure exists at the time of Panel establishment, at least findings must be made. Such a solution would recognize the value of WTO dispute resolution as offering certainty and predictability regarding the interpretation of the WTO covered agreements for all WTO Members, including Members having in place similar measures. At the same time, given the text of Article 19.1 of the DSU, the default rule should be that recommendations be made. Whilst such recommendations might be linked to the continuing effects of the expired measures, ultimately there is little difference between full and qualified recommendations. Regardless of the type of recommendation, the availability of implementation proceedings requires showing that measures have been taken that comply or have a sufficient nexus with the measures forming the object of the original Panel and Appellate Body proceedings. Put differently, the approach to the question of findings and recommendations in relation to expired measures could be simplified given that ultimately it is the scope of jurisdiction under Article 21.5 of the DSU and the evidence of measures falling within that jurisdiction that determine the value of findings and recommendations in a particular dispute.

Finally, it should be recognized that had the delay in the case been avoided, the strength of the European Union's arguments would have been significantly reduced. It would have been clearer that there was a dispute regarding measures still in force (at least) up to the final stage of the proceedings.

4. Government Revenue Foregone in Case of Duty Drawback Schemes

A duty drawback scheme typically involves refunds of paid import duties or the exemption of such duties on inputs, when the goods using the inputs are exported following inward processing. An input is imported subject to the payment of relevant import duties. When the good in which it was used as an input is subsequently exported again, the exporter is entitled to a refund of the import duty previously paid. Under a properly administered scheme, the imported inputs and duties paid are accurately recorded and the refund (or remission) will correspond with the duties paid on the inputs used in the exported goods. Thus, where not all inputs are used specifically for goods that are subsequently exported, no refund is to be obtained with respect to the inputs that were not used. Where a refund in connection with the inputs that were not used, specifically for goods that are subsequently exported, is nonetheless obtained, it is a benefit foregone by the government.

Duty drawback schemes are based on the theory that manufacturers should not bear import duties on imported goods that are never released for circulation in that market but are exported after being processed (Branton, Reference Branton1999). Duty drawback schemes are frequently used to avoid distortion on international markets and, in particular, ‘double taxation’. Highly protected developing markets use such schemes for improving the domestic industry's export competitiveness and for creating indirect tax incentives for foreign direct investment (Iancovichina, Reference Ianchovichina2007).

Duty drawback schemes, if remitting duties to exporting firms in excess of the permitted amount, in essence create an unfair advantage for the exporting firms over producers that serve only the domestic market. From that perspective, a duty drawback scheme that leads to excess remission of duties paid can be viewed as an export subsidy. In contrast, a simple zero MFN import tariff on inputs would not be an export subsidy given that it benefits all producers in the same manner.

The SCM Agreement lays down the specific conditions under which duty drawback schemes are (not) subsidies. In essence, the main principle is that an exporter may not receive a greater remission (that is, a refund) than the amounts of duties or taxes that have accrued. If that condition is not satisfied, then there is a subsidy. The main question in EU–PET (Pakistan) was whether the amount of the subsidy is the difference or the total amount of the remission.

The provisional determination in the underlying investigation took issue with the fact that Pakistan did not apply a proper verification system to determine the amount of duty-free imported inputs consumed in the production of the goods subsequently exported and found that the MBS was a countervailable subsidy contingent in law upon export performance. The benefit was defined as the remission of total import duties normally due upon importation of inputs. Thus, all the unpaid duties were revenue foregone and could be countervailed. That position was confirmed in the definitive determination. Before the Panel, Pakistan claimed that that finding of the European Union was contrary to Articles 1.1(a)(1)(ii) (including footnote 1) and 3.1(a) of the SCM Agreement. The European Union appealed against the Panel's reliance on the so-called ‘excess remissions principle’, meaning that the financial contribution, in the form of government revenue foregone, is limited to the excess amount of the remission.

Although the exemption of duties or taxes or remission (including the refund or rebate of taxes) may constitute government revenue, footnote 1 to Article 1.1(a)(1)(ii) lists instances of government foregone that ‘shall not be deemed to be’ subsidies. Annex I(1) specifies that duty drawback schemes apply to import charges levied on imported inputs that are consumed in the production of the exported product.

The Appellate Body underlined three features of footnote 1: (i) ‘the comparison to be made is between the tax treatment of the inputs imported under the duty drawback scheme that are consumed in the production of the goods destined for export, on the one hand, and the ‘duties or taxes borne by the like’ imported input ‘when destined for domestic consumption’, on the other hand’ (para. 5.100); (ii) only the amounts ‘not in excess of those which have accrued’ are not deemed to be a subsidy’ (para. 5.101); (iii) footnote 1 expressly refers to the conditions in Annexes I and III.

Thus, the central question was what effect to give to a lacking, inadequate, or ineffective verification system.

The Appellate Body read together the Ad Note to Article XVI of the GATT 1994 of which the language is identical to part of footnote 1 of the SCM Agreement (para. 5.107); the illustrative list of export subsidies in Annex I to the SCM Agreement, in paragraphs (g), (h), and (i) (and in particular paragraph (i) and footnote 58 regarding duty drawback schemes) (paras. 5.109–5.110); and Annexes II and III relating to, respectively, the consumption of inputs in the production process and the determination of substitution drawback schemes (para. 5.111). Annex II also made it clear that ‘the examination into the consumption of inputs is an intermediate task in the investigating authority's inquiry into whether there was excess drawback of import charges’ (para. 5.115). A more extensive examination is required only in case the investigating authority has determined that there is no verification in the exporting Member or the verification system in place is not adequate or not effectively applied (para. 5.121). In that event, the investigating authority must inform the exporting Member of the need for a further examination in a sufficiently detailed and timely manner, in order for it to be able to defend its interests during the remaining part of the countervailing duty investigation (para. 5.122).

The Appellate Body thus found that Article 12.7 of the SCM Agreement applies in case an investigating authority decides that the exporting Member lacks an appropriate verification system, has not effectively applied a verification system, or has not (satisfactorily) carried out the requested further examination. Pursuant to that provision, an investigating authority may resort to facts available (para. 5.129). In any event, according to the Appellate Body, any perceived silence does not relate to the definition of what is a financial contribution for the purposes of the definition of a subsidy but concerns ‘a procedural step in the context of an investigating authority's inquiry into whether the excess remission or drawback occurred’ (para. 5.131).

The Appellate Body therefore concluded that ‘duty drawback schemes can constitute an export subsidy that can be countervailed only if they result in a remission or drawback of import charges ‘in excess’ of those actually levied on the imported inputs that are consumed in the production of the exported product’ and therefore ‘the financial contribution element of the subsidy … is limited to the excess remission or drawback of import charges and does not encompass the entire amount of the remission or drawback of import charges’ (para. 5.134).Footnote 24

The Appellate Body's position appears to find a clear basis in the text of the SCM Agreement. It strikes an even-handed balance between, on the one hand, the obligations of the exporting WTO Member and, on the other, the responsibilities of the investigating authority. At the same time, by focusing on the distinction between a countervailable subsidy and the procedural obligations of the investigating authority, the Appellate Body appeared to postpone till a later day a definitive answer to the question of whether an investigating authority may nonetheless decide, following its inquiry into whether the excess remission or drawback occurred by asking further questions to the exporting Member and following responses from that Member, that the countervailable subsidy comprises the entirety of the remissions. Facts available may be used but that option appears to be subject to a procedural framework that is not yet fully developed as a result of this report. In practice, the option of using facts available might involve a considerable burden on an investigating authority because it will be required to show that it has, on its written record, information regarding the details of the operation of the (deficient) verification system used by another country. Using facts available is also not the same as drawing adverse inferences because the process does presume the existence of facts that can be objectively determined. At the same time, given that the appropriateness of using facts available depends very much on the particular circumstances of a case, in practice authorities often consider that they enjoy considerable freedom in resorting to that procedure. Ultimately, the Appellate Body's refusal to agree with the European Union might be based on a general consideration that the lack of some verification system of the exporting Member does not necessarily mean that, taking into account also the principle of good faith, a Member has fully foregone verifying what inputs have been used for subsequently exported goods.

5. Economic Analysis of the Causation Methodology

The Appellate Body rejected Pakistan's claims under Article 15.5 of the SCM Agreement regarding the flaws in the Commission's causation analysis and upheld the Panel's findings that the use of a ‘break the causal link’ approach was consistent with Article 15.5 of the SCM Agreement.

5.1 Determination of Initial Causal Link

The first part of the findings relates to the Commission's two-step ‘break the causal link’ methodology: first, if an initial link between investigated imports and injury is being established, then other factors that could have contributed to the injury should be considered. Pakistan had argued that the Commission's two-step methodology precluded it from satisfying the non-attribution requirements in order to determine ‘whether other known factors “attenuate” or “dilute” the link found between the subsidized imports and the injury such that this link cannot be characterized as a “genuine and substantial relationship of cause and effect”’ (paras. 5.162–5.163). The European Union responded that it had properly distinguished the effects of other known factors. It also considered the use of the words ‘breaking’, ‘attenuating’, or ‘diluting’ to be a matter of semantics (para. 5.164).

The Appellate Body noted that Article 15.5 does not lay down a particular methodology for that purpose. It followed that investigating authorities are free to choose the methodology to employ (para. 5.172). What matters is that the authority objectively determined that the subsidized imports constitute a genuine and substantial cause of the injury after taking into account the injurious effects of other known factors (para. 5.178). The Appellate Body therefore agreed with the Panel that Article 15.5 does not preclude an authority from making an initial consideration of the causal link between completing its non-attribution analysis and then reaching an overall conclusion on the existence of a causal relationship (para. 5.180).

Whilst the Appellate Body's insistence that Article 15.5 of the SCM Agreement imposes no singular methodology for establishing the causal link between the injury and subsidized imports appears to be justified, the two-step methodology used by the Commission nonetheless shows some crucial weaknesses. Economic theory suggests that the lack of simultaneous analysis of relevant factors (as was the case in the Commission's methodology) may preclude, as Pakistan had argued, a proper causal analysis because imports themselves are endogenous to other factors. For example, Horn and Mavroidis (2003, Section 5) have previously underscored that, in US–Lamb, the USITC had failed to conduct a proper causal analysis due to the lack of a simultaneous analysis of various factors.Footnote 25 Similarly, Mitchell and Prusa (2016) have discussed, in their analysis of China–Autos, that overreliance of investigating authorities on correlations and trends without simultaneous analysis is a shortcoming because a multitude of contributing factors change at the same time.

5.2 Pakistan's Objections to the Standard of Causation

5.2.1 Internal Inconsistency of the Methodology

Pakistan argued that, even if Panel did not err in its decision that the Commission's methodology did not necessarily preclude it from separating and distinguishing various injurious effects, the Commission's methodology in practice fell short of a complete and objective causation analysis (paras. 5.184–8.185).

Pakistan categorized the alleged flaws in the Commission's methodology into four claims.

First, according to Pakistan, a causal link should never have existed if other injurious factors are capable of breaking the causal link (para. 5.186). The Appellate Body rejected Pakistan's claim. It found that, although the phrase ‘break the causal link’ was unfortunate, its use was in essence a matter of semantics and the Commission had compared the relative significance of other injurious factors rather than determined whether the impact of each factor is so large as to negate the link between the subsidized imports and the injury (paras. 5.192–5.196).

The position that the problems of the ‘break the causal link’ methodology concern merely semantics is unfortunate. The Commission had determined that the impact of two other injurious factors (imports from Korea and economic downturn) was limited in comparison to the investigated imports (para. 5.192). For example, the Commission concluded that the contribution of imports from Korea ‘was only limited and they are considered not to have broken the causal link established as regards the subsidized imports’. However, the Commission did not assess whether the injurious impact of imports is reduced, or attenuated, due to the imports from Korea (Provisional Determination rec. 249). A complete non-attribution analysis would have considered, when moving to the other factor, only the injurious contribution of imports net of the injurious effect of previously considered factors.

Causation analysis can lead to a fallacy if attenuating effects are not explicitly taken into account. Consider the example in which injury is caused by four factors: investigated imports and three other factors. Assume also that the ‘true’ injurious impacts are such that the investigated imports contribute to 40% of the injury, while three other factors contribute each 20%, together making up 60% of the injury. In this example, each other factor has a limited impact relative to the investigated imports. If the non-attribution analysis stops at determining that each other factor has a limited impact relative to the investigated imports, it will attribute the injury to the investigated imports, and will thus not be complete and objective. However if the attenuation effect of each factor with limited impact would be taken into account by the investigating authority, it would appear that investigated imports cause only 40% of the injury. Then the investigating authority would have had to assess whether the remaining contribution of the investigated imports could still be considered genuine and substantial.

Such a complete analysis can be carried out in two stages, and a collective analysis of the three other factors is not required. However, it is important to incorporate attenuating effects of each other factors, or the investigation risks significantly overstating the injury due to investigated imports.

Pakistan in essence suggested that the Commission's approach fell short of a complete and objective causation analysis. This point can be illustrated by applying the Commission's approach to our example. The Commission's methodology would imply that the initial relationship between investigated imports and injury is established. Next, the Commission would consider each of the three other factors. In each case the Commission would correctly find that the impact of each individual factor is limited compared to that of the investigated imports (which is the case as each factor contributes only half as much as the investigated imports). Crucially, under the Commission's methodology, it would be sufficient to find that each factor's impact is limited relative to the investigated imports, without the need to consider the attenuating effect on imports before proceeding to the next other factor. The Commission would then conclude that none of the considered factors breaks the causal link. However, using that methodology, the Commission would fail to determine that in fact 60% of the injury was caused by other factors, thereby not properly separating and distinguishing between the attenuating effects of other factors.

The discrepancy between the Commission's approach and a complete causation analysis is important because it might impact the overall conclusion. An authority might have concluded after a complete analysis that, as 60% of the injury is caused by other factors, the relationship between the injury and imports is no longer genuine and substantial.

The fallacy of Commission's approach in the example could have been present in this case as well. The Commission found two injurious factors besides subsidized imports. The Panel found that the Commission had acted inconsistently with the SCM Agreement in its analysis of the impact of another two factors – oil prices and competition from non-cooperating producers – it is thus possible that these factors have contributed to the injury as well.

The Appellate Body also rejected Pakistan's argument that the Commission had established the causal link based on ‘the mere fact that the subject products secure[d] part of the market and somehow contributed to the overall injury’ (para. 5.197). It found that the Commission had considered that ‘PET is a commodity and competition takes place mainly via price’ and that ‘the lower priced subsidized imports that had increased their volume and market share drastically’ caused the injury to the domestic industry that ‘manifested itself in, inter alia, negative trends in production, sales, market share and profitability’ (para 5.198). In other words, the Appellate Body took the view that the injury consists of negative trends on a number of indicators, and that the Commission had assessed the impact of subsidized imports based on a number of indicators of the state of the domestic industry.

The Appellate Body found that ‘the Commission observed that the following six economic indicators showed negative trends during the period considered: production; sales; market share; profitability; return on investment; and cash flow’ (para. 5.149). However, in its investigation, the Commission observed only a negative trend in market share of domestic producers. In addition, it found an end-point-to-end-point, between 2006 and the investigation period (IP), decrease in production, sales, profitability, and return on investment. The Commission was careful to distinguish the end-point-to-end-point decrease from a negative trend and did not claim anywhere in the Provisional Determination that the minor decreases between 2006 and the IP formed a negative trend.

The ‘considered period’ for the Commission's injury assessment is 2006–2008 and the IP (July 2008–June 2009). During the considered period (recitals 218–240 of the Provisional Determination):

• the market share of domestic producers showed a negative trend (it decreased each period);

• domestic sales showed a mild end-point-to-end-point decrease of 3%. However, they peaked in 2005 with sales 5% above the 2006 level and the 2008 value was only 1% below the 2006 value;

• although domestic production, profitability, and return on investment showed end-point-to-end-point decreases, the trends of those indicators were far from negative: the highest levels were in 2007, considerably above the 2006 value and they all showed an increase in the most recent period: between 2008 and the IP; notably those three indicators showed a fall only in 2008; and

• cash flow of the domestic producers showed an end-point-to-end-point increase and increase in the most recent period between 2008 and the IP; this indicator fell relative to previous period only in 2008.

The distinction between end-points analysis and trends should not be underestimated. In fact, four out of the six mentioned indicators (production, profitability, return on investment, and cash flow) fell only once relative to the previous period: in 2008. The market share of imports was increasing every period, so if the main cause was imports, these indicators would show a clear negative trend. Instead, they were increasing each period relative to the previous one, and it was only in 2008 that they seriously fell. This points to economic downturn as a potential cause of that fall. Worth noting, those four factors all showed an improvement between 2008 and the IP. The Panel report (footnote 329) discusses the importance of the most recent portion of the considered period of the investigation.

The lack of clear negative trends in sales, production, profitability, return on investment, and cash flow highlights the Commission's overreliance on the domestic market share in its injury determination. Increases in consumption demand between 2006 and the IP by 11%, combined with mild changes in production and sales, reduced the market share of domestic producers from 85% in 2006 to 75% during the IP. The inability to capture increased demand, despite available capacity and the resulting decrease in market share, caused the Commission to conclude that the domestic industry suffered material injury (recitals 238–240 of the Provisional Determination).

Overall, it seems clear that the Commission established the causal link based solely on the market share (and volume) of imports. Specifically, the Commission found that domestic producers lost their market share while lower-priced investigated imports increased their market share (recital 242 of Provisional Determination). The fact that PET is a commodity is a fact relevant for the Commission's analysis only to the extent that, while weighted average price undercutting of 3.2% is below 4%, the price undercutting is not insignificant (recital 243). Finally, the Commission concluded that subsidized imports created a downward price pressure on the market and caused overall injury to the industry in the form of lower sales and profits (recital 245). However, the Commission did not assess (e.g., by focusing on trends or a correlation analysis) the impact of the investigated imports on any of the six indicators of the state of the domestic industry other than the domestic market share.Footnote 26

Thus, the Commission found that the domestic industry’ material injury was caused by the investigated imports due to a coincidence in time of increases in imports and market shares from investigated countries, on the one hand, and the worsening of the state of the domestic industry, on the other. In fact, the Commission used the same statistical trend (increased imports) for determining both injury and causation (recitals 238–240 of the Provisional Determination). Surprisingly, the fact that the injury was established primarily based on the falling domestic market share did not receive due attention in the dispute.

5.2.2 Consequences of Analyzing Each Factor Individually

The Appellate Body considered Pakistan's second argument that, by examining whether each of the other known factors individually broke the initial causal link, the Commission had ‘assessed the effects of each non-attribution factor against the effects of the subsidized imports plus the effects of the remaining non-attribution factors’ (para. 5.200). Pakistan's claim was straightforward from an economic perspective. It was based on the understanding that the injury (the outcome variable) is a function of multiple economic factors that simultaneously affect each other. When any factor, or variable, is considered individually (i.e., alone) in assessing its impact on the outcome variable (injury), then its effect is indeed assessed against the total, compounded, effect of all factors that determine that outcome variable. In other words, Pakistan argued that assessing separately the effect of each relevant factor on a variable that is a function of a number of factors might result in a bias known as ‘omitted variable bias’ and might preclude identifying the true impact of either of the considered factors.

The Appellate Body rejected Pakistan's argument, finding that the ‘Commission assessed the significance of the injurious effects of each non-attribution factor against the link that it had found to exist between the subsidized imports alone and the injury suffered by the EU industry’ (para. 5.202). Thus, the Appellate Body understood Pakistan's concern regarding the impacts of different factors when compared to each other. However, Pakistan claimed that by considering individually the impact of each factor on a variable that is an outcome of various economic factors, the impact of each factor itself is potentially not correctly identified.

5.2.3 Even-Handedness of the Commission's Approach

The Appellate Body found no support for Pakistan's third argument that the Commission's causality analysis was not even-handed due to its use of a low causation threshold for the subsidized imports and a higher one for the other factors (para. 5.213). Pakistan had argued that, given that Article 15.4 requires an examination of the impact of investigated imports on the domestic industry based on all relevant economic factors, the non-attribution requirements of Article 15.5 require a similar analysis for other factors. The Appellate Body ruled that Article 15.5 does not require an authority ‘to assess the impact of the other known factors in the exact same manner as its analysis of the impact of the subsidized imports under Article 15.4’ (para. 5.217; original emphasis).

The finding that Article 15.5 does not require an examination of other factors in exactly the same manner is not necessarily problematic. In this case, it is difficult to imagine how the non-attribution analysis can be correctly implemented without conducting the exact same impact assessment. It could be argued that an objective test of whether any other factor ‘breaks the causal link’ between imports and injury should assess these other factors in exactly the same manner as the method applied when establishing the initial relationship with imports.

5.2.4 Attenuation Analysis

Finally, the Appellate Body disagreed with Pakistan's objection that the Commission's methodology tainted the analysis of the non-attribution factors ‘and precluded the Commission from properly separating and distinguishing the effects of those factors’ (para. 5.186). The Appellate Body found that Pakistan's objection was not clear. However, the Appellate Body nonetheless addressed the objection as if it was related to the use of the term ‘break’ and rejected the claim on the same grounds as the first objection (para. 5.221).

However, the intrinsic disadvantage of the Commission's two-step approach is that, as economic factors simultaneously affect each other, it might be impossible to properly separate the effects of different factors when assessed individually. For example, the Commission found that, although the economic downturn contributed to the domestic industry's injury, subsidized imports made the negative impact of the economic downturn worse. The Commission argued that the economic downturn strengthens the case against the role of the investigated imports. However, the Commission's methodology did not consider the possibility of reverse causality, namely that the economic downturn affected the competitiveness of the domestic industry, pushing domestic prices up and creating endogenous demand for lower-priced imports.

6. Conclusion

The report in EU–PET (Pakistan) did not definitively resolve the question of whether the design and function of the WTO dispute settlement system require or preclude findings on expired measures. By contrast, the report usefully clarifies, in respect of duty drawback schemes, that the investigating authority may consider as a subsidy only the remission paid in excess of the amounts due. In particular, the lack of some verification system of the exporting Member does not necessarily mean that, taking into account also the principle of good faith, a Member has fully foregone verifying what inputs have been used for subsequently exported goods. The appropriate response of an investigating authority in such circumstances is to resort to facts available. Finally, the Appellate Body rightly concluded that any methodology for the causation analysis should be permissible as long as it results in a complete and objective analysis. However, it appears that the methodology used by the investigating authority in this case showed a number of deficiencies that were raised by Pakistan but not recognized by the Appellate Body.