It is now recognized that the nutrition transition engulfing South-East Asia has both healthy and unhealthy dimensions: the first involves access to affordable dietary diversity increasing for large numbers of national populations, and the second involves relatively easy access to affordable high-energy processed foods(Reference Hawkes1). Both trends begin with relatively affluent urban populations(Reference Mendez and Popkin2). However if Western trends are any guide, as the health penalties of the second aspect of the transition become known, affluent groups generally moderate their consumption in line with advice from various health authorities(Reference Offer3). If other subpopulations continue with their consumption of high-energy processed foods, then diet-related health inequalities widen(Reference Hawkes1).

Within the context of debates about what forces are responsible for the transition, the role of food retailers bears examination(Reference Hawkes1, Reference White4). Questions are being asked about the role of different food retail formats in encouraging the consumption of new diets, their control over food supply chains, and their claims to deliver healthy diets. Of particular interest in OECD countries is the displacement of small food retailers as a result of supermarket/hypermarket activities(Reference Simms5) and evidence that some supermarket home-brand products may be of inferior nutrition quality(Reference Bourke6).

While these controversies are ongoing, there is some agreement that large retailers are well positioned to influence food preferences and food acceptability. In a review of the evidence about supermarket impacts on diets, Hawkes(Reference Hawkes7) concluded that their promotional activities – including making a loss on certain items – contributes to altering consumer shopping patterns and subsequent consumption.

As part of an ethnographic investigation into the contribution to Thai social and economic dynamics of fresh markets and European hyper/supermarkets, the current paper reports on a small investigation into the food beliefs and preferences among Chiang Mai shoppers in northern Thailand. The study builds upon research conducted 20 years earlier, when questions were asked about the centrality of rice in Thai culinary culture(Reference Walker8). That study found that young and wealthy Bangkok residents were likely to place less value on rice in their diets than people living in the northern region of Thailand, where Chiang Mai is the capital. The current research investigates whether Chiang Mai is following Bangkok with regard to this particular food trend and if this trend is also linked with shopping in a setting that connotes novelty and modernity in contrast to a traditional setting such as a fresh market.

This research does not present evidence of increased unhealthy food consumption although other researchers have indicated that the Thai diet is changing(Reference Kosulwat9, Reference Aekplakorn, Hogan and Chongsuvivatwong10), that weight is increasing in the Thai population, and that its distribution is changing(Reference Aekplakorn, Chaiyapong and Neal11). Rather it assumes the nutrition transition is present(Reference Kosulwat9, Reference Banwell, Lim and Seubsman12) and searches for initial indicators of whether fresh market and supermarket shoppers have similar food attachments with possible implications for weight gain. The research rationale was twofold. First, a shift in preference to higher energy-dense bread and baked goods is of concern in terms of population-level weight gain given the evidence that these foods are partly responsible for the increased sugar consumption noted in a Thai (student) population(Reference Promdee, Trakulthong and Kangwantrakul13). Second, there is mounting concern for the way that the globalizing food retail sector is ‘increasing pressure for global dietary standardization’(Reference Duchin14). This trend constitutes a health risk for countries like Thailand, whose culinary culture (based on rice, fish and plant foods) is generally acknowledged to be healthy at the population level. Thus health promotion authorities would benefit from knowing about the shifts in the value sets being used to guide food purchases.

Methods

In order to recruit the sample, an Australian anthropologist and a bilingual Chiang Mai resident collected data intermittently over two months in 2008 during a complementary ethnographic investigation in south-west Chiang Mai in 2008(Reference Isaacs15). A total of sixty people within four fresh markets, and within the food courts attached to two supermarkets, were approached. Participants were recruited as part of a convenience sample, which was determined by the spaces of investigation: commercial, public and informal places of consumption.

Sixteen people declined to participate; being ‘too busy’ was the most common explanation that was offered. When the numbers of regular shoppers at both fresh markets and supermarkets reached about fifteen people and a smaller number who shopped at both had been interviewed, it was determined that no new response themes were being identified and that a sufficient saturation of data had been collected for a preliminary investigation.

Interviews were conducted with the forty-four participants, who comprised seventeen regular supermarket users, seventeen regular fresh market users and ten people who consistently shopped at both supermarkets and fresh markets. A short accompanying questionnaire was used to collect information about their sex, age and labour force status, and they were asked about their shopping preferences and frequency at supermarkets and fresh markets. A set of closed questions about values concerning three foods followed, beginning with: ‘No meal is complete without rice’, ‘I never feel full unless I eat rice’ and ‘Rice is the perfect food’. This line of questioning was prompted by Walker’s(Reference Walker8) 1990 study on Bangkok foodscapes, with respondents being asked if they strongly agreed, agreed or disagreed with the statements. We then repeated this form of questioning with respect to bread and baked wheat products, and finally to wheat noodles. By ‘baked wheat products’ most people referred to bakery items like bread, cakes and biscuits. Responses to other foods contributing to the nutrition transition such as pizzas and fast foods were not investigated. The goal of the study was to examine cultural evaluations around three ‘staples’ that would have dietary relevance to the largest number of people and that might offer a comparison with the 1990 Bangkok study.

A code list was developed based on codes which either reflected participants’ responses or drew upon consensus in current literature on the nutrition transition. It was applied to all open-ended interview data. After repeated readings, coded segments of text were sorted into major themes or patterns of ideas(Reference Huberman and Miles16). The answers to the closed questions regarding rice, baked products and wheat noodles were sorted and counted.

Findings

Table 1 shows the age breakdown of the participants. The age brackets used are the same as used by Walker. Nine of the respondents were men.

Table 1 Age distribution of participants, Chiang Mai, northern Thailand

While there was some difference by age, the most striking association in preferences for rice, bread and wheat noodles was determined by where people shopped, rather than their labour force status or age group. Although older respondents commented that young people eat more fast food and international foods than they do or did at their age, the young respondents held very similar values to their elders about rice and bread being perfect or filling. For example, 90 % of 19- to 24-year-olds and 88 % of people aged 45 years and older agreed or strongly agreed that rice was the ‘perfect’ food.

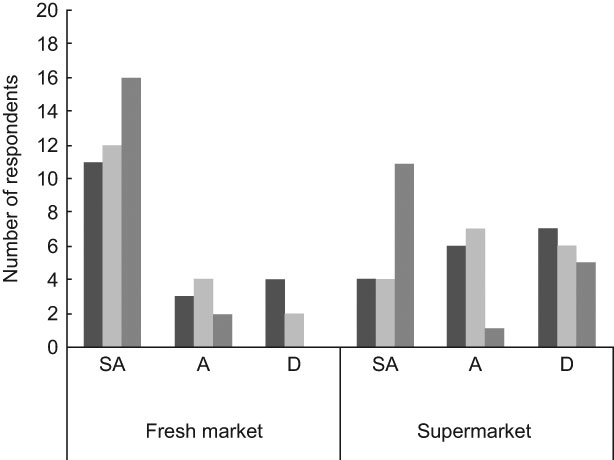

While the findings (presented in Figs 1–3) do not include an age breakdown, they show different food valuations according to whether people are regular supermarket or fresh market shoppers. We do not report separately on regular shoppers at both sites, but their responses confirm the tendency for lower valuations of rice and higher valuations for bread and bakery among regular supermarket shoppers.

Fig. 1 Rice preferences among fresh market and supermarket shoppers, Chiang Mai, northern Thailand. Responses are shown according to whether participants ‘strongly agreed’ (SA), ‘agreed’ (A) or ‘disagreed’ (D) that rice ‘completed’ a meal (![]() ), made them feel ‘full’ (

), made them feel ‘full’ (![]() ) and was the ‘perfect’ food (

) and was the ‘perfect’ food (![]() )

)

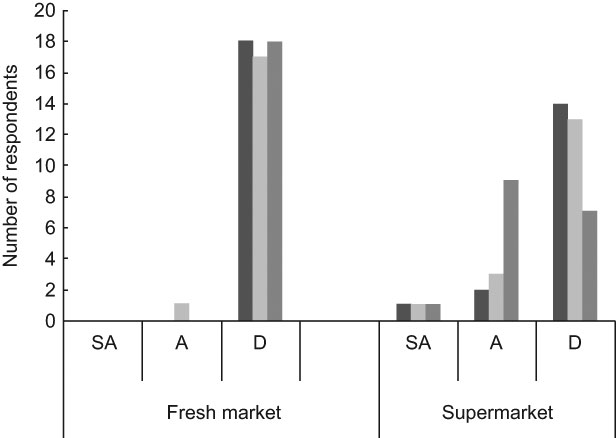

Fig. 2 Bread and bakery preferences among fresh market and supermarket shoppers, Chiang Mai, northern Thailand. Responses are shown according to whether participants ‘strongly agreed’ (SA), ‘agreed’ (A) or ‘disagreed’ (D) that bread and bakery products ‘completed’ a meal (![]() ), made them feel ‘full’ (

), made them feel ‘full’ (![]() ) and was the ‘perfect’ food (

) and was the ‘perfect’ food (![]() )

)

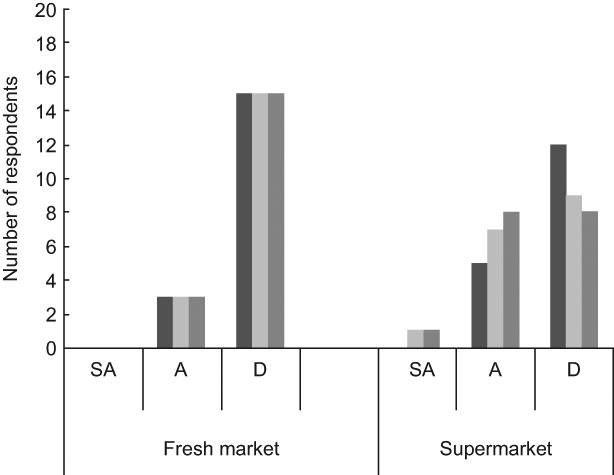

Fig. 3 Wheat noodle preferences among fresh market and supermarket shoppers, Chiang Mai, northern Thailand. Responses are shown according to whether participants ‘strongly agreed’ (SA), ‘agreed’ (A) or ‘disagreed’ (D) that wheat noodles ‘completed’ a meal (![]() ), made them feel ‘full’ (

), made them feel ‘full’ (![]() ) and was the ‘perfect’ food (

) and was the ‘perfect’ food (![]() )

)

Rice

Figure 1 demonstrates that regular fresh market shoppers were more likely to ‘strongly agree’ with the statements ‘No meal is complete without rice’, ‘I never feel full unless I eat rice’ and ‘Rice is the perfect food’. One young woman echoed a familiar sentiment when she said ‘Thai people like the smell of rice, the smell of what is good’. Figure 1 also suggests that regular supermarket shoppers are similarly likely to affirm the symbolic importance of rice, with a majority choosing ‘strongly agree’ to the statement ‘Rice is the perfect food’, although a notable five out of seventeen supermarket shoppers disagreed with this statement. Further, despite assuming the symbolic importance of rice they were less likely to consider that rice was essential to ‘completing’ a meal or feeling ‘full’.

Preferences for rice were also linked by respondents with particular food behaviours and family life. One respondent, Fah, explained:

The young students who live by themselves, they prefer noodles because it is easier to cook… But for us we have to cook every day for the family and it is better. There is more quantity, with noodles there is only one thing but with rice the meal is bigger and you can have many types of food.

Bread

Supermarkets are the key suppliers of bread-based culinary practices across the country, although large cities have specialist bakery shops. In Chiang Mai, a majority of consumers would be introduced to bread in the supermarket. Figure 2 reports on bread and bakery preferences.

Figure 2 indicates that, with one exception, regular fresh market shoppers were in complete agreement that ‘bread and baked wheat products’ were not adequate to make one ‘full’, to ‘complete’ a meal or to be counted as a ‘perfect’ food. Fah said:

When we eat bread sometimes we are not full, so we have to eat bread and rice in the same meal and it is more expensive.

Those who shopped at the supermarkets were also likely to agree that bread did not make one ‘full’ or ‘completed’ one’s meal. However those who shopped regularly at supermarkets were more likely to ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ that bread was the ‘perfect food’. Some supermarket shoppers described this ‘perfect’ quality by bread’s ‘convenience’ (particularly convenience for travel), while others explained bread’s ‘perfect’ quality by the bakery smell and the suitability of bread and bakery products as a complement to coffee.

Wheat noodles

Preferences for wheat noodles, which show the least difference between those who shop at fresh markets and at supermarkets, are reported in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 suggests a slightly greater tendency among those who shop at supermarkets to agree that wheat noodles are ‘perfect’, make one feel ‘full’ and ‘complete’ a meal. Respondents disconnected from the labour force, and hence assumed to have less income, sometimes remarked that noodles are more expensive than feeding a family on rice.

Discussion

In other studies, fresh markets in Asia are the major purveyors of local vegetables, fresh food and a traditional, rice-based diet(Reference Figuie and Moustier17). They are also associated with the ‘plastic bag housewife’ who is seeking small amounts of affordable ingredients and conveniently prepared meal contributions(Reference Yasmeen18, Reference Dixon, Banwell and Seubsman19). In contrast, supermarkets are associated with cleanliness and a modern approach to selling packaged groceries(Reference Goldman, Krider and Ramaswami20). This distinction was confirmed by our participants in the semi-structured part of the interview.

Typically supermarket shoppers have higher disposable incomes or higher education(Reference Kosulwat9), making them more receptive to being early adopters of new trends, including shopping practices. As the present study was a qualitative, purposive-sample design we do not know if the numerical and qualitative association between supermarket shoppers and adoption of novel culinary ingredients is widely generalisable. Furthermore, as we have conducted simple descriptive statistical analysis which is appropriate to the study’s design and small sample size, we do not know if these results are statistically significant. A more complex issue is one of causality. We also cannot know whether those who start shopping at supermarkets begin to change their cultural values about food at that point or prior to the supermarket experience. Informed by various social histories of the impact of supermarkets it is assumed that there are intertwined webs of influences which cause shifts in food preferences and values(Reference Humphery21). What is notable from the Chiang Mai sub-study is that supermarkets support a particular dietary lifestyle.

As noted by Fah, the traditional culinary model across South-East Asia has been for families to sit as a group and share a meal of several different dishes(Reference Seubsman, Dixon and Suttinan22). This practice is readily facilitated by fresh markets; and while supermarkets do sell pre-packaged fresh and frozen ‘ready-to-eat meals’ in single servings, these meals are not conducive to sharing. Instead, they are designed to be eaten by individuals away from the group.

The adoption of favourable attitudes towards farang foods, like bread, might be the unintended consequence of health promotion as much as supermarket promotion. Lefferts argues that in recent years the Thai government has maligned regional foods such as sticky rice and plaa raa (fermented fish) as ‘unhealthy’. Health authorities have prescribed an avoidance of such ‘rural’ and regional foods (especially those originating from the poorer north-east Isan region) without giving advice about which Western-style foods should also be avoided(Reference Lefferts23). These stigmas are emerging amid growing fears of obesity and new Western-influenced ideals about body image(Reference Duchin14).

Discourses about ‘clean’ and ‘healthy’ food were evident among some of the respondents in the current project. One woman who shopped at the supermarket acknowledged her unusual preference for bread over rice by saying that bread was a softer smelling, more sanitised food. Another supermarket shopper, when asked if she felt if foreign foods or Thai foods were healthier, said:

We do eat some healthy Western foods like milk and some bakery food… At my house I try to encourage to eat two things in the morning. Rice and milk and bread. Milk is always included in the meal.

While other respondents suggested milk and cheese were contributing to obesity, this quote suggests that some people attempt to incorporate a bread-based diet into their lives as a healthy option, providing a complement or alternative to rice.

The universal views regarding wheat noodles reflect the popularity in Chiang Mai of two main sources of wheat noodles: the instant, packaged noodle variety and the small restaurant/noodle stall. Respondents from both food retail formats and of all age groups and labour force status backgrounds described how wheat noodles were ‘tasty’. Several people commented on how restaurant wheat noodles were a healthy choice because they included meat and vegetables. Wheat noodle popularity reflects another reason for the esteem of fresh markets and other forms of small-scale retailing: they provide convenient ah-han an duan, Thai ‘fast’ food.

The research has important implications for Thailand’s health authorities. First, it may be advisable to develop a campaign to reverse any stigma surrounding rice consumption. Interestingly, appeals to its popularity in the West may assist here because it is generally recognized that per capita rice consumption is rising in rice-importing countries(Reference Pingali24). Second, as is beginning to happen elsewhere, the government needs to monitor the provision of reliable information about the sugar, fat and salt content of processed foods, including bakery and instant noodle dishes. Retailer self-regulation on nutrition panels has been found deficient in the UK(Reference Dibb25).

Conclusion

The current research cannot tell the motivations for Thais who shift their shopping from fresh markets to supermarkets, but other studies suggest that identification with the social status of a modern citizen is partly responsible(Reference Walker8, Reference D’Haese, Van den Berg and Speelman26). What it does suggest is that regular supermarket shoppers value the bread and bakery products because they contribute to a feeling of fullness or are the ‘perfect food’, even if they then go home and eat rice to complement the state of completion. At the very least, supermarkets are supporting changing food preferences which may be more energy-dense than traditional foods.

Acknowledgements

The research for this paper received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector. Full ethical approval for the project was granted by the University of Sydney. The authors have no conflict of interests to state. The author contributions to this paper are the following. Collection of data, specific analysis and creation of tables were carried out by B.A.I. Critical reflection and further analysis were carried out by J.D., C.B. and B.A.I. Acknowledgments and thanks are given to Bongkot Theppiman for her interpretation work in collecting the data that form the basis of this paper. The authors would also like to acknowledge the research of Marilyn Walker whose questionnaire designed to investigate food values among Thais in Bangkok in the 1990s was appropriated for this project. Marilyn Walker is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Mount Allison University, Canada.