Introduction

Despite an era marked by swift technological and organizational changes, the historical significance of Taylorism and its interplay with the twentieth-century political economy has waned in contemporary academic discourse. However, a renewed interest in these topics can contribute to public discussions while encouraging more academic interest in the potential impact of local trade union activism on social and economic policy. While there are noteworthy exceptions, economic and social historians today predominantly focus on institutional and econometric models that seldom consider the influence of worker agency.Footnote 1

This article examines a specific aspect of the relationship between Taylorism and labour market policy. I argue that worker agency and local trade union activism have historically played a significant role in shaping the institutional framework of labour markets. Drawing on the trade union history of Taylorism in Sweden, I demonstrate how several institutional aspects of the “Swedish labour market model” can be traced back to tensions between workers and employers over scientific management. More specifically, I provide insight into how worker resistance to scientific management was manifested, what the workers’ concerns were, and how, ultimately, this resulted in a series of central agreements between trade unions and employers in the 1940s. The article highlights the importance of examining the dynamics between different levels of industrial relations, in particular the relationship between workers and management on the shop floors, the relationship and discussions within trade unions, and, finally, the relationship between central labour market organizations. Although extensive research was done on the subject in the 1980s and 1990s, this crucial aspect has not received sufficient attention in contemporary research.Footnote 2

It is not my intention to present the Swedish case as historically unique. Rather, the article points to the minor variations in the logic of Taylorism across Europe. The changes in the production process and industrial relations that occurred in Sweden coincided with similar developments in most industrialized capitalist countries from the interwar period onwards. Nevertheless, variations in political and social contexts resulted in different aspects of Taylorism being highlighted or underemphasized – a process Judith Merkle has named “the nativization of Taylorism”.Footnote 3

The vast literature on Taylorism that emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century has underscored the distinctions between American and European Taylorism during the interwar period. Many scholars have suggested that European Taylorism highlighted the political implications of Taylorism, where the “Americanist” ideology of social stability and high labour productivity was perceived as ideal. The German case has garnered particular attention, with scholars pointing to the influential role of labour in the Taylorist-inspired “rationalization movement”. In Germany, efforts to increase labour productivity were linked early on with attempts to secure social stability and promote public welfare within the framework of liberal corporatism.Footnote 4 While the rationalization movement in Germany, as in much of Europe, was interrupted by the fall of the Weimar Republic and World War II, Sweden stands out as an interesting exception. The combination of Sweden's political stability, the ascendance of a reformist labour movement, the concurrent organized rationalization movement, and the country's neutrality during World War II, allowed for a more complete nativization of Taylorism than in most European countries. Whereas rationalization movements throughout Europe ended in the 1930s, in Sweden they intensified during the same period. The importance of rationalization in the negotiations between labour and capital in the 1930s and 1940s warrants more international attention.Footnote 5 This provides a compelling backdrop against which the influence of worker resistance and local trade union activism can be studied extensively and effectively.

However, the Swedish case was not a Sonderweg; the importance of studying it does not lie in essentialist explanations of twentieth-century Sweden. My goal is to illuminate the subtle interplay between local trade union deliberations and the formulation of a broader national labour market policy. The article indicates that what may appear as a smooth evolution of labour–capital relations was, in fact, a contested process. This evolution emerges as a process marked by tensions and negotiations, where the persistent efforts of the rank-and-file became a significant force.

The material consists of documents from a workers’ organization related to the Swedish Metal Workers’ Union (MWU), which brought together trade unionists from workshops that were part of the multinational Separator Corporate Group (now Alfa Laval). Separator was a pioneer in adopting scientific management in Sweden, and the worker–management relationship at the corporation had an important impact on the discourse regarding Taylorism within the MWU. The article also includes MWU congress and conference minutes, revealing the connection between local trade union discussions and broader national trade union policy. Together, this material illuminates the pivotal role of rank-and-file activism in shaping the MWU's and the Swedish Trade Union Confederation's (LO) policies, and later the “Swedish labour market model”. Rationalization and industrial relations were sector-wide concerns that resonated across the working class. However, the MWU's involvement, as the largest and most influential member of the LO, acquires heightened importance, having significantly impacted industrial relations and policy in Sweden. As I show in this article, the MWU's stance towards rationalization is a crucial chapter in the history of the Swedish trade union movement.

An important point is that what occurs on the shop floor and in local union activism can compel central labour market organizations to formulate new policies. This article strives to answer how worker resistance to scientific management in Sweden manifested itself, what concerns workers voiced, and how these dynamics culminated in a series of central agreements between trade unions and employers in the 1940s. This is not to imply that workers got all that they desired. It simply reveals that their will and their desires had an impact on what they got.

Taylorism and the Rationalization Movement in Sweden

Frederick W. Taylor's ideas on scientific management, often known as Taylorism, emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a response to increased industrialization in the United States. Taylorism sought to increase labour productivity through the scientific analysis of work processes, the standardization of tasks, and the introduction of incentive wage systems that encouraged competition among workers.Footnote 6 This approach was closely connected to the advance of industrial society and the necessity to manage and regulate labour in large industrial enterprises. Moreover, it aimed to overcome the conflicts between labour and capital by developing a system that combined high productivity, technocracy, and social stability. On the shop floor, Taylorism was manifested through the active involvement of management in the production process and the introduction of methods and systems such as time-motion studies and piecework to raise productivity and gain control over the shop floor.

The origins of Swedish Taylorism can be traced back to the legacy of Frederick Taylor's Swedish counterpart Erik August Forsberg. After observing applied scientific management in the United States at the turn of the century, Forsberg was hired by Separator in 1902. Forsberg later became the company's chief engineer and served as a board member. Beginning in the early 1900s, Separator became the first Swedish company to implement scientific management in its work organization. The company was established in 1883 with a specialization in milk separators, before diversifying into the metal and engineering industries in general. Separator expanded rapidly during the early twentieth century through acquisitions and the establishment of new subsidiaries in Sweden, the United States, Germany, and Italy. Separator and its Swedish subsidiaries emerged as one of the largest companies in the country. By 1950, the Separator Corporate Group had a workforce of over 5,000 in Sweden, 4,000 of whom were blue-collar workers.Footnote 7

While piecework was already widespread in the manufacturing industry at the end of the nineteenth century, Separator began experimenting with premium bonus systems in 1902, designed to encourage competition among workers by linking wages to individual productivity. Forsberg developed the system further along Taylorist lines, so that, by 1907, piecework rates were determined by time studies. According to Forsberg, a key characteristic of the system was that workers did not comprehend it and, consequently, found it hard to manipulate. Around 1910, disputes arose between management and workers at one of Separator's subsidiaries.Footnote 8 In 1915–1916, a sequence of strikes and lockouts finally compelled Separator to concede on some aspects of its new piecework system. Despite abolishing the premium bonus system and increasing worker involvement in the labour process, the management continued to hold the authority to determine piecework rates. As Alf Johansson concludes, Separator partly gained from the agreement because workers faced challenges in formulating an alternative system. He contends that reducing labour productivity remained workers’ primary tactic for regulating the labour process even after 1916.Footnote 9

The events that occurred in the 1910s illustrated the limits of scientific management in Sweden. Swedish trade unions had already cemented their position as a considerable power after the metal workers' strike of 1905, which, in the following year, led employers to acknowledge the unions as the legitimate representatives of the working class. According to Johansson, “Taylorism arrived to Sweden too early and too late. It arrived too early given the technical structure of the factories. It arrived too late to defeat the trade unions”.Footnote 10 Even though Taylorism arrived too late to defeat the unions, attempts to gradually undermine them persisted. Johansson posits that the labour movement's resistance to scientific management was, indeed, “one of the driving forces of modernization and rationalization”.Footnote 11 Based on the events in 1915–1916, Forsberg wrote:

That the ancient principle in question has only in our days taken shape, so to speak, and developed into a science is of course due to a number of reasons, one of which – and perhaps not the least important – is to be found in the modern labour movement. In spite of the good it has undoubtedly brought about in some respects, it cannot be denied that it has sought to regulate the labour market in such a way as to inhibit the production of the individual worker, to the great detriment of both industry and the economy of mankind as a whole. To oppose this tendency with only a general demand for an increase in the intensity of labour is in fact merely to set power against power, something which may succeed in individual cases but does not, however, provide a real solution to the difficulties. Here, as everywhere else, only knowledge is real power, and thus the desire has arisen to provide a real, objective basis for determining how much can and should be produced.Footnote 12

Two years after the publication of Taylor's magnum opus in 1911, Separator's Forsberg wrote the preface to the Swedish translation of The Principles of Scientific Management.Footnote 13 The translation was published by the newly established Sweden's Industrial Association (Sveriges Industriförbund), which, together with the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA), became an important organization in the rationalization movement. A number of organizations were established in the 1910s and 1920s to promote scientific management and other practices such as psychotechnics.Footnote 14 In the early 1920s, the interest in Taylorism evolved into a German-inspired “rationalization” (rationalisering) that conceptually replaced scientific management. Hans De Geer argues that the Swedish concept of “rationalization” was a product of American scientific management as well as German psychology and business administration.Footnote 15 The explanation for this likely lies in the fact that increased labour productivity in Sweden also depended on modernizing the industrial machinery and the outdated structures of Swedish companies. Scientific management, by itself, could not bring about fundamental changes in Swedish industry. This does not imply that Taylorism gave way to the rationalization movement. On the contrary, the principles of scientific management were deeply ingrained in both the practice and ideology of rationalization. As Paul Devinat put it in 1927, rationalization in Europe was “a rather irregular and haphazard extension of Taylorism in all directions”.Footnote 16

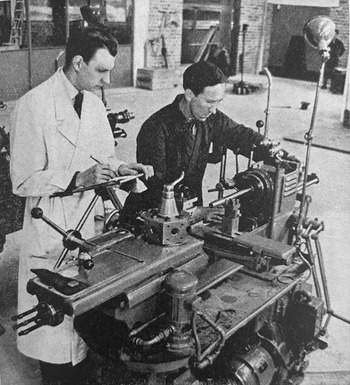

The economic crisis of 1921–1922 led to mergers of failing companies in Sweden, which later came under pressure to rationalize. A wave of electrification and mechanization followed. In the 1930s, employers became increasingly interested in sophisticated time-motion studies, called work studies (arbetsstudier), as an advanced form of rationalization (Figure 1).Footnote 17 The reason why this aspect of scientific management attracted particular interest among Swedish employers can be partly explained by the fact that piecework and the employers’ right to manage had been accepted by the trade union movement as part of the 1906 General Agreement. Unlike, for example, differential piecework systems, as a result of the 1906 compromise piecework in general and time-motion studies in particular were never challenged by the unions. Consequently, although one of the slogans of the German trade union movement in the 1920s was “Akkord ist Mort!”, the Swedish trade unions had accepted piecework as an unavoidable reality.Footnote 18 Therefore, the most applicable aspects of scientific management in Swedish industry were the control and monitoring of workers through time-motion studies, the transfer of knowledge to planning offices, worker grading, and “scientific” calculation of piece rates.

Figure 1 Time studies researcher analysing a metal worker, Lidköpings Mek. Verkstad, c.1943.

Vi på Kulan, Christmas edition 1943 (not paginated).

As in Europe, rationalization and social stability became a primary objective for the Swedish government in the 1920s. During this period, Sweden had one of the highest incidences of industrial actions per capita amongst Western countries.Footnote 19 Concurrently with the British Mond-Turner talks on rationalization and industrial peace, the Swedish Conservative government launched an initiative in 1928 to start negotiations between LO and the Swedish Employers’ Association (SAF) on the same topics. The discussions centred on how to achieve social stability and how both parties could cooperate to enhance economic growth. In contrast with the failed British Mond-Turner talks, the negotiations between labour and capital in Sweden were successful. A significant dissimilarity between Britain and Sweden was the robust position of the Swedish labour movement compared to its British counterpart, which had encountered numerous defeats in the 1920s.Footnote 20 The Swedish talks eventually collapsed during the Great Depression, but resumed after the economic recovery. This time, they were conducted under the auspices of the Social Democratic government, which demanded a resolution to the industrial disputes. The Saltsjöbaden Agreement was signed in 1938, which formally established class cooperation between the LO and the SAF.Footnote 21 The state was also a de facto party to the agreement, not as a signatory but as the ultimate guarantor of social and economic stability, using the threat of political legislation as a means to ensure compliance. This landmark agreement represented the embodiment of social corporatism, i.e. a state-sponsored class cooperation grounded in mutual interest, which served as the prevailing political ideology in Sweden.Footnote 22

However, cooperation at the national level did not always reflect on the shop floor. Unofficial disputes over piecework and time-motion studies surged during the early 1940s.Footnote 23 By that time, most major manufacturing firms started to use time-motion studies to increase productivity and set piecework rates. Despite incomplete data from the Metal Trades Employers Association (MTEA), the increase in mentions of disputes over time-motion studies and piecework indicates a rise in tensions between workers and employers. Reports from Statistics Sweden show that the official strike count decreased after the Saltsjöbaden Agreement in 1938, but increased again between 1942 and 1946.Footnote 24 We have reason to believe that the figures would be higher if the reports had taken into account unofficial strikes relating piecework rates and time-motion studies. While employers asserted their right to manage the shop floors, workers argued that time-motion studies weakened their bargaining position and increased work intensity.Footnote 25

Worker Resistance to “Rationalization” at Separator

The Separator Group Workshop Clubs Association (SGWCA) was formed in 1928 by workers at Separator and its subsidiaries. The organization comprised local workshop clubs that organized workers at various workplaces. In 1929, the association consisted of four clubs affiliated to the MWU and one affiliated to the minor Swedish Foundry Workers’ Union. The clubs had varying sizes, with the largest organizing over 1,000 workers while the smallest had between 100 and 200 workers. By 1950, the association had expanded to include nine workshop clubs within the Separator Corporate Group.Footnote 26 The association organized annual conferences that brought together around thirty representatives from the workshops to discuss common concerns.

It remains unclear what moved the workers to form the organization. However, the timing suggests a possible connection to Separator's increased rationalization efforts at the end of the 1920s. These efforts were already a central theme at the organization's first conference in 1929. At the conference, the workers came to the conclusion that the corporation's ongoing rationalization had increased labour intensity without adequate compensation to the workers. The conference attributed the lack of wage reduction attempts by management, despite increased productivity, to local worker resistance.Footnote 27 The discussions about rationalization carried on during the two subsequent conferences in 1930. At this time, the Great Depression was taking its toll on the Swedish metal and engineering industry. The unemployment rate within the MWU increased from 7.2 per cent in 1929 to 19.8 per cent in 1930. The rate reached its highest point in 1932 at 29.8 per cent, before starting to decrease the following year. It was not until 1936 that it fell below the 1929 level.Footnote 28

The correlation between rationalization and unemployment was central at the conferences held during the economic crisis. Indeed, it was the most discussed topic within the Swedish trade union movement.Footnote 29 One of the participants at the association's conference in 1930 held rationalization responsible for the crisis, a prevalent view in both the Swedish and European labour movements.Footnote 30 Although other participants refrained from making similar accusations, the discussion eventually centred on the advantages and disadvantages of rationalization. Despite the conference agreeing, as voiced by one speaker, that “[o]ne should not be a machine breaker”, there was a shared understanding that rationalization had not yielded any gains for workers. As another attendee asserted, “[w]e have been misunderstood when we talk about impeding rationalization. When we say that we will not take part in the rationalization process, what we mean is that workers should not contribute to deskilling and further reducing the number of jobs”.Footnote 31

The conference expressed strong criticism towards time-motion studies. Discussions revolving around this issue would dominate the conferences for decades as work studies, a more advanced form of time-motion studies, emerged as the primary means of rationalization in Swedish industry as of the 1930s. Time-motion studies were viewed as a threat, not so much as an alienating approach to production but as a game-changer. Whereas workers previously had more knowledge than management about the inner workings of the workshop, time-motion studies and the Taylorist philosophy behind them risked undermining their advantage. For both workers and management, time-motion studies were changing “the rules of the game”.Footnote 32 In 1930, the workers were divided over whether to oppose time-motion studies altogether, as some argued that the previous system for calculating piecework rates was also flawed. However, they agreed that the minimum base from which piecework rates were set needed to be increased. The issue was that the workers were not involved in the actual calculation.Footnote 33 It was essential for the workers to regulate the work pace and “that each workshop club informs [the workers] at their meetings how to behave when time-motion studies are carried out”.Footnote 34

Tensions between the MWU Membership and Leadership over Rationalization

In 1930, the association decided to ask the MWU to investigate the impact of time-motion studies on working conditions. As per the workers, the situation on the shop floor had worsened as management began using time-motion studies more aggressively. During the conference in 1931, a participant cited a case where people conducting time studies had covered the clocks on the wall with cloth to prevent workers from keeping track of the time.Footnote 35 A few years later, one of the workshop clubs announced that it had bought clocks to lend to workers during time-motion studies.Footnote 36 At one of its conferences in 1930, the association decided to request the companies to provide copies of the time-study sheets to the workshop clubs for future comparisons. This proved difficult for most clubs due to the management's reluctance to share that information with workers.Footnote 37

In the early 1930s, rationalization had become one of the most debated concerns in the Swedish trade union movement. This coincided with an organized push by employers to reduce wages due to the economic downturn. At the same time, as unemployment among MWU members rose, labour productivity and the number of engineers in the metal and engineering industry increased.Footnote 38 The trade union movement's mistrust of rationalization was therefore unsurprising. Rationalization was the most dominant theme in most editions of the MWU's weekly journal Metallarbetaren (The Metal Worker) as well as other labour movement publications. Rationalization was also a central issue at the 1931 LO congress. The MWU branch in Gothenburg, known for its radicalism, had submitted a motion that sparked heated debates. The motion proposed that LO established an office dedicated to developing the trade union movement's policy on rationalization.Footnote 39 Even though the motion was voted down, it had a lasting effect on the movement's general discussion. After the 1938 MWU congress, the union would revisit a modified version of the proposal.Footnote 40

Separator's workers decided to present an almost identical motion to the 1932 MWU congress. The motion emphasized that:

From the workers’ point of view, we have no objection to time studies if they are carried out in a completely objective and decisive manner. As things stands at the moment, we have no knowledge whatsoever of the calculations and calculations’ minimum base, and we have no way of verifying the results of the time studies, which are absolutely essential for us if we are to get a share in the benefits of rationalization.Footnote 41

The motion suggested that the MWU establish an office dedicated to rationalization, including time-motion studies. The purpose of the office would be to support workshop clubs in negotiating piecework rates and to prevent employers from exploiting workers’ limited technical knowledge. One worker observed at the association's conference in 1932 that, even if they had managed to obtain copies of the time-motion studies in 1930, comprehending them remained a problem. Another worker stressed at the conference that, “we too must use science to our aid, just as the employers do”. He also mentioned how the time-study researchers in his workshop had noticed irregularities in the work pace that had aroused management's suspicions. It was therefore important “that we do not work one time carefully and with interest and another more casually […] we must do our best to keep the same work pace, at least when time studies are carried out”.Footnote 42

The 1932 MWU congress marked a showdown between the leadership and the communist-led opposition. Communists and radical social democrats proposed motions asserting that time-motion studies undermined the position of workers on the shop floor. Moreover, many contended that the high unemployment figures were a result of rationalization. The MWU's central committee, in contrast, argued that workers should not resist rationalization because it eventually facilitated higher wages and shorter working hours. The central committee focused “on promoting members’ interest during the rationalization process”. Although most motions did not call on the union to actively resist rationalization, they did argue that rationalization should be followed by demands for significant reductions in working hours. Ultimately, the central committee narrowly won most of the votes.Footnote 43 Despite being a setback for the opposition, membership support for tougher action against rationalization increased in the following years.

Fighting Knowledge with Knowledge: Education as a Form of Resistance

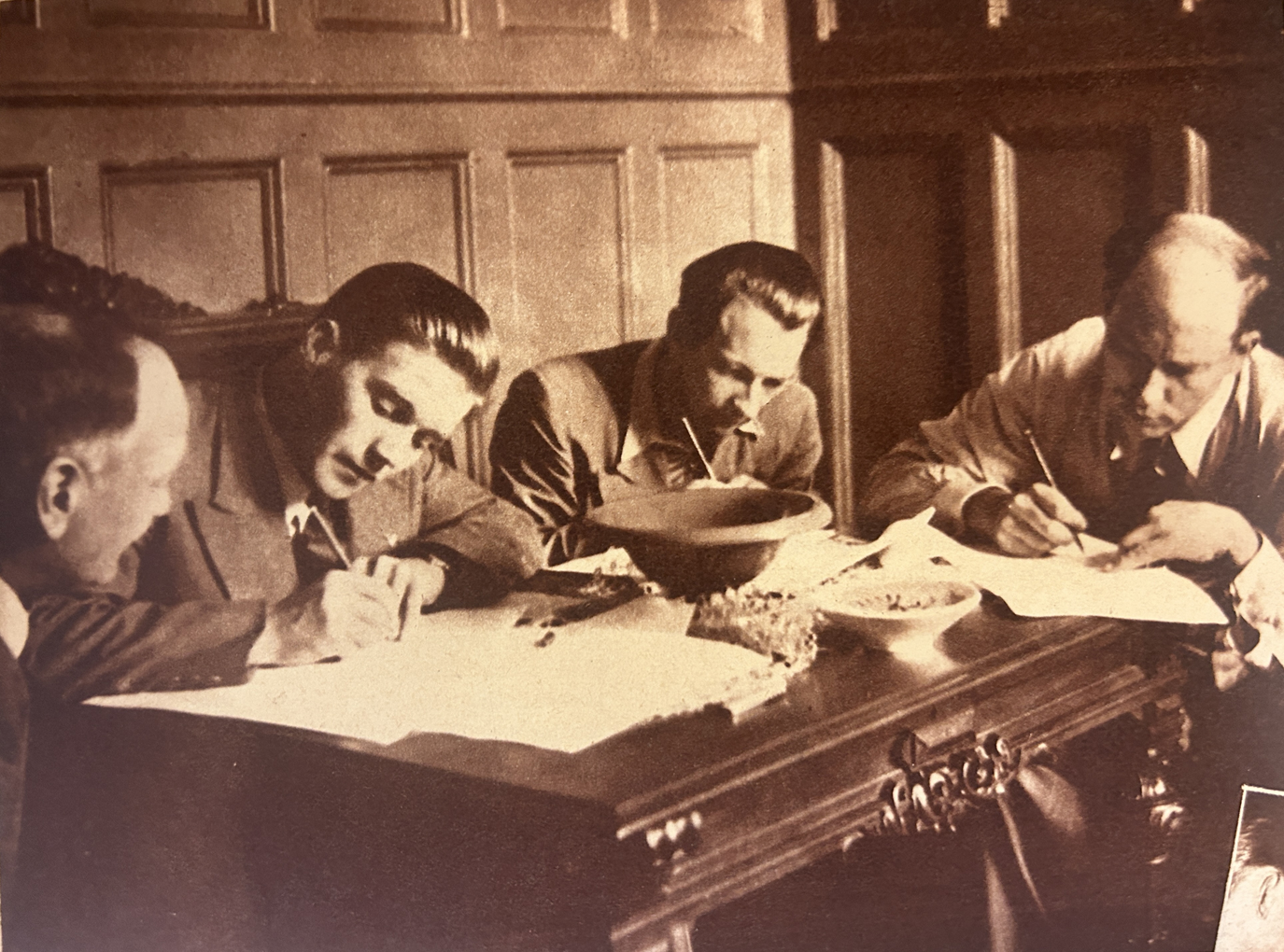

Separator's workers continued to challenge time-motion studies despite their defeat at the 1932 congress. Following their defeat, the association planned local study circles to acquire knowledge about time-motion studies. By 1933, the workers had identified appropriate study material for the circles, and the association urged the clubs to establish circles in their respective workshops.Footnote 44 Study circles of this kind were rare in 1933, but by the 1940s they had become prevalent in large workshops in Sweden. The circles taught participants how time-motion studies were conducted and analysed, and how piecework rates were calculated based of them. Knowledge was perceived as the primary method for workers to regulate management's efforts to control the shop floor. Separator's workers concluded that the corporation's growing monopoly on knowledge needed to be challenged, partly through self-education.Footnote 45 Rationalization would also become an important theoretical issue for the Swedish labour movement. An illustration of this are the numerous courses and study circles on the topic that the national Workers’ Education Association organized during this period (Figure 2).Footnote 46

Figure 2 Participants in the MWU's Time-Motion Studies Course.

Metallarbetaren, 5/7 (1944) (nr. 27, year 55), p. 8.

However, Separator's workers came to the conclusion that study circles were not sufficient. The economic boom following the Great Depression led to a significant influx of new workers, many of whom came from rural areas with no prior working-class experience. In the 1940s, an increasing number of new workers came from the Baltics.Footnote 47 As early as 1935, the association identified the lack of experience and tacit knowledge of the new workers of the inner workings of the factories as a major problem. The discussion surrounding rationalization and unemployment was replaced by one concerning rationalization and the balance of power. For instance, workers noted that management was conducting time-motion studies on newly hired workers who had not received training from the union. During the 1935 conference, one worker claimed that they lacked the time to organize their new colleagues owing to their vast number and inexperience. There was a concern that it could have a detrimental effect on piece rates.Footnote 48 Another worker reported to the 1938 conference that:

When piece rates are set and offered, we are not allowed to look at the time studies, we have to take what we are offered and be happy with it. It is also difficult to get the members to stand up for themselves. Most of them come from completely rural backwaters and are happy with what they are paid and are afraid of being fired.Footnote 49

In 1935, the association made the decision to produce a pamphlet designed for new workers. The pamphlet would provide details about their duties to the union and how they were supposed to conduct themselves on the shop floor. This was particularly important when time-motion studies were conducted.Footnote 50 The first draft was distributed the next year, and the clubs provided feedback before the subsequent conference. The MWU's vice-chairman attended the conference in 1936 and openly disapproved of the idea of a pamphlet. He argued that employers might retaliate by publishing a pamphlet of their own, which could trigger a series of problems. Despite the vice-chairman's advice, the association proceeded with the plan.Footnote 51

Discussions regarding the pamphlet continued for several years. The issue also resulted in talks with the MWU's central committee, who feared a possible propaganda battle with the employers. By the late 1930s, Separator's workers were not alone in confronting time-motion studies and scientific management. Between 1930 and 1949, the proportion of wages in piecework with the metal industry was constantly above eighty per cent for skilled workers and semi-skilled workers. Yet, the percentage of piecework determined by time-motion studies increased significantly. In 1930, only twenty-seven factories in the Swedish metal industry, employing fewer than 30,000 workers, utilized time-motion studies. An internal MTEA survey showed a large increase by 1943, with at least 213 factories employing almost 83,000 workers using time-motion studies. According to the same study, seventy-six per cent of all piecework rates set in MTEA affiliated companies were calculated using time-motion studies.Footnote 52

The members of the MWU were becoming significantly dissatisfied with time-motion studies. As a result, the union's leadership had to tackle the problem. The MWU's central committee faced a defeat at the 1938 congress, where it agreed to create an internal group to “investigate what measures should be taken to provide the members of the union with a fuller understanding of the problem of time-motion studies and the contractual rights that exist in this area”.Footnote 53 Curiously, in December 1938, when the LO and the SAF (supported by the MWU's leadership) were achieving industrial peace and cooperation at the national level, the disputes within the trade union movement concerning time-motion studies and piece rates escalated. A similar trend also occurred on the shop floors. To some extent, disputes relating to piecework and time-motion studies shifted from being between workers and employers to become a matter between workers and the LO–SAF coalition.

The Separator workers’ association suspended its plan to print a pamphlet while awaiting the outcome of the internal investigation. Later, in 1938, the MWU's central committee announced the publication of a work studies handbook for use in study circles, which would also address members’ concerns. The handbook was published in 1940, five years after the Separator workers' first discussions. Notably, the handbook was co-written by a corporate engineer, revealing the leadership's stance on work studies and worker–management relationships. The handbook was also based on the work of the renowned engineer Tarras Sällfors, who was a prominent figure in the Swedish rationalization movement.Footnote 54 The handbook presented a positive view on time-motion studies and general employer–employee cooperation. The book argued that work studies should be used more extensively, albeit raising some minor concerns. For instance, it argued that:

[A]s far as the workers are concerned, the most important advantage [of work studies] is that the piece rates are set on a more objective basis, so that, for example, the personal sympathies or antipathies of the supervisor are eliminated […] Moreover, the worker is given the opportunity to see the figures and the calculations on which the payment is based. Negotiations can therefore be based on real facts. For this reason, it is desirable, or rather necessary, for workers to become familiar with the technique of work studies. In this way, any suspicion that he is being “cheated” is removed, as he will be able to see for himself whether the piece rates are correct or not. The more both employers and employees become familiar with work studies and their application, the less friction there will be in negotiations and the like, since their expertise will guarantee a fair calculation of wages, which is one of the prerequisites for a worker's well-being at work.Footnote 55

The book's views on work studies as a method of bringing workers and employers together was consistent with the MWU's and the LO's overall policy following the Saltsjöbaden Agreement of 1938. The agreement established class cooperation between the LO and the SAF with the aim of achieving industrial peace and improving the conditions for long-term economic development.

However, on the shop floors, worries about the impact of work studies on workers increased rapidly. The union leadership's view on scientific management and class cooperation was at clear odds with the membership's.

The Time-Motion Studies Dilemma and the Paradox of Industrial Relations

The years that followed the Saltsjöbaden Agreement of 1938 were paradoxical in many ways. Despite the LO and the SAF establishing new forums for cooperation, the Swedish trade union movement was divided in its position towards the employers. Nevertheless, the centralization of the collective bargaining system in the 1920s had weakened local union activism, allowing the central organizations to act more independently. Alf Johansson and others argue that the impact of local unions on industrial relations became weaker during the inter-war period and that, “external factors brought about a balance of power in which time-motion studies, rationalization, and higher labour intensity had to be accepted by manufacturing workers. It is an important explanation for the coming ‘industrial peace’ and the Saltsjöbaden Agreement at the end of the inter-war period”.Footnote 56 The contradictory nature of Swedish industrial relations during the early days of the Saltsjöbaden Agreement was most evident on the shop floors. Even though the leadership of both the MWU and the LO favoured class cooperation, shop-floor disputes escalated during the late 1930s and early 1940s. Nevertheless, the agreement was a crucial event that marked the victory of corporatism and served as the foundation of Swedish industrial relations in the post-war period.

In 1937, a member of the MWU central committee had been invited to speak at the Separator workers’ conference, which was held one year before the signing of the Saltsjöbaden Agreement. He argued that time-motion studies were inevitable, a statement that triggered frustration among conference participants. The guest pointed out that the collective agreement permitted workers to negotiate piece rates, regardless of whether time-motion studies had been conducted or not. The conference accused the leadership of being too lenient on time-motion studies. The workers claimed that, in practice, they were unable to negotiate piece rates with management due to the collective agreement's imprecise formulations regarding time-motion studies. In contrast to the guest's assertions, the conference decided to write a formal letter to the MWU central committee, expressing the workers growing concerns about time-motion studies.Footnote 57

A union representative from Separator's largest subsidiary, which employed around 1,400 workers, reported conflicts in his workshop in 1939. The conflicts resulted from rationalization and “the constant reduction of piece rates”. He also reported that management had hired American engineers specializing in rationalization, which had increased tensions. The disputes between the workers and the Americans had resulted in a large protest, following which the company had sacked five workers in response. This resulted in what the speaker referred to as Sweden's first “sit-down strike”. The conference concurred that the situation was no longer tenable. The workers decided to raise the matter once more during the forthcoming collective bargaining negotiations, which would determine the union's demands in the negotiations. The association's demands sharply contrasted with the MWU's handbook, published a year later. The letter argued that time-motion studies had raised labour intensity without a matching increase in wages. The letter concluded that, “[t]he theorists’ conception of rationalization in the form of time-motion studies as beneficial to the interests of both employers and workers has proved, as far as the workers are concerned, to be an assumption which has rarely if ever been realized”. The workers argued that rationalization had not led to higher wages and that the wage increases in previous collective agreements were “illusory simply because the provisions on piecework in our agreement are so vague and, in any case, give the employers enormous room for arbitrariness and thus the possibility of thwarting a collective agreement, including general wage improvements”. Therefore, Separator's workers suggested that the union demanded fixed and pre-determined piece rates during the negotiations.Footnote 58

The conference held in 1940 was devoted to discussions about time-motion studies. The association had invited the chief engineer of one of Separator's subsidiaries and a representative of the MWU, who was also the co-author of the union's work studies handbook. The chief engineer argued that time-motion studies ought not be a source of contention between workers and management as both parties benefitted from them. He emphasized that the studies did not aim to analyse the workforce, but to analyse the work. The engineer provided a detailed description of how the studies were conducted and highlighted that they demonstrated how, in some cases, workers purposefully lowered their productivity.Footnote 59 The MWU representative had a slightly different and less enthusiastic view of time-motion studies. He began by saying that Separator's management was one of the most challenging to negotiate with, and that other employers displayed more understanding of workers’ concerns. Nevertheless, preventing time-motion studies from being implemented was not feasible. It was still essential, however, for the workers to ensure that the time-motion studies were conducted objectively. He contended that workers should organize study circles and make sure that they do not rush when time-motion studies were carried out. He also mentioned that in previous negotiations with the MTEA, the MWU had attempted to introduce clauses regarding time-motion studies, but failed due to shortage of time.Footnote 60 The fact that the MWU did not deliberate on time-motion studies in the negotiations implies that the issue was not on the priority list, despite the membership's opinions. At the same time, it signalled a shift in the leadership's policy concerning time-motion studies. The mounting dissatisfaction of the members increased the pressure on the leadership to address their worries.

Although the leadership was hesitant, the discussion on time-motion studies and piecework continued in the association and among metal workers as a whole. By the early 1940s, study circles and courses in time-motion studies became widespread within the MWU and the Workers’ Education Association. Workshop clubs at the Separator Corporate Group also developed new methods to counteract the adverse effects of time-motion studies. Register systems were introduced by a few clubs to retain information about time-motion studies and piece rates. Their objective was to reproduce the corporation's technique for acquiring knowledge from time-motion studies. These archives could then be employed during talks with management.Footnote 61

Worker Radicalization and the Great Metal Strike of 1945

Tensions in the labour market increased during World War II, in part as a result of the radicalization of the entire trade union movement. In 1945, the MWU branches in major cities, including Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö, were predominantly dominated by communists. This was the result of a combination of factors. They included escalation of local disputes over reduced real wages and time-motion studies, a growing dissatisfaction with the union leadership's perceived failure to tackle these problems and, to some extent, the emerging sympathy with the Soviet Union's military advancements. The increasing power of communists within the MWU was a hard blow to the union leadership. At the beginning of the war, both the LO and the MWU intensified their campaign against the communists. In 1941, the MWU implemented a controversial decision to forbid communists from holding representative office within the union.Footnote 62 After receiving heavy criticism from the members, the MWU finally lifted the ban in 1944.Footnote 63

The association put together a motion for the 1944 congress, in which they reiterated their stance that the union must hire professionals who were specialized in time-motion studies. This was far from the only motion about work studies. Despite gaining access to time-motion studies results in the 1936 collective agreement, workers were still unable to decipher them, highlighting the need for professionals in time-motion studies to be employed. Insufficient knowledge remained a major problem. Moreover, the association contended that time-motion studies made some workers nervous and worried, and that employers exploited this by targeting them for studies. The result was lower piece rates for everyone. Separator's workers additionally issued a statement urging the policy conference for the upcoming collective bargaining to address the ongoing problems related to time-motion studies.Footnote 64

However, the motion to the congress was withdrawn as the MWU changed its position to some degree in 1944. Negotiations with the MTEA resulted in a non-binding clause in the collective agreement, asserting that workers had the right to request time-motion studies, that employers should take into account the opinions of their employees before conducting the studies, that both parties should agree on a minimum basis for piece rates, and, finally, that both parties “loyally participate in ensuring that the time-motion studies give correct results”.Footnote 65 Despite the relatively moderate wording, the MWU leadership denied that the non-binding clause was the result of internal pressure from the membership. The leadership insisted that the circumstances for amending the agreement had simply become more favourable.Footnote 66

The policy conference in 1944 was a disaster for the MWU leadership. Following the lifting of the ban on communists, the policy conference proceeded to elect communists and so-called independents, i.e. members not affiliated to a political party, to the majority of positions in the negotiating delegation.Footnote 67 Most of the membership, including the communists, advocated for the reinstatement of real wages to pre-war levels. Real wages for skilled workers in the Swedish metal industry had fallen by seven per cent in 1944 compared to 1939.Footnote 68 While higher wages were the main point of discussion at the policy conference, time-motion studies also came to the fore. Furthermore, it was increasingly difficult to separate the wage question from time-motion studies as a growing number of piece rates were based on them. The leadership, on the other hand, maintained that significant wage increases could create an inflationary spiral, which could harm Swedish industry. They argued that the MWU should concentrate on improving wages for the lowest paid members. This did not resonate with the conference which insisted on pushing for higher wages and greater influence over time-motion studies and piece rate calculation.Footnote 69

The collective bargaining between the MWU and the MTEA in 1944 ended in deadlock after the MTEA refused to restore wages to their pre-war levels. The MTEA, furthermore, responded to the MWU's demand for greater influence over time-motion studies by refusing to discuss time-motion studies. This caused considerable irritation among the MWU delegation. One of the MWU delegates later remarked that time-motion studies were now one of the most critical issues.Footnote 70

In February 1945, the MWU, along with the minor Swedish Foundry Workers’ Union, called a nationwide strike involving 123,000 workers (Figure 3). The strike went on for five months and still holds the position of the second largest strike in Swedish history, after the general strike of 1909. The MWU and the MTEA eventually agreed upon a wage adjustment that resulted in some disappointment as the deal failed to restore the pre-war real wages. The agreement was, however, a significant improvement compared to the MTEA's first proposal, which did not include any wage increases at all. Following the strike, a debate ensued after the communists publicly blamed the MWU's leadership and the LO for undermining the strike in various ways. The MWU leadership and the LO responded by accusing the communists of manipulating the members during the policy conferences.Footnote 71 However, the chairman of the LO admitted that there were some material bases for the metal workers to go on strike, time-motion studies being among the most important.Footnote 72

Figure 3 Striking metal workers demonstrating in Gothenburg, 8 April 1945. The banners say, “For Victory in the Metal Strike”.

Swedish Labour Movement's Archives and Library.

Despite the disappointments, the strike had an important long-term impact on industrial relations in Sweden. The agreement between the MWU and the MTEA included a clause that entitled workers to complete information on how time-motion studies were conducted and how piece rates were calculated. Besides, the agreement established a work studies committee comprising representatives from the MWU and the MTEA. The committee's objective was to resolve disputes concerning time-motion studies and piece rates, marking an important step in resolving the work studies problem. The strike coincided with negotiations between LO and SAF that resulted in the creation of “company councils” (företagsnämnder) in 1946. Under the agreement between the LO and the SAF, companies with at least twenty-five employees would establish councils made up of worker and employer representatives. The councils would allow workers to participate in economic and production-technical decision-making. The participation of workers in the rationalization process was one of the councils’ primary goals. This represented an important victory for the reformist labour movement, which had advocated for “industrial democracy” since the 1920s. Employers envisaged that the councils would bring social stability and improve the conditions for labour productivity growth.Footnote 73 This corresponded with a broad tendency within the business community to move away from “militant” to a “soft” Taylorism that viewed class cooperation as a precondition for sustained rationalization.Footnote 74 For employers, the developments of the 1930s and 1940s secured their “right to manage” and organize the workshops, while also agreeing to include workers in the decision-making. Consequently, the Saltsjöbaden Agreement signed in 1938 and the series of agreements in the 1940s were victories for Swedish corporatism.

The Work Studies Agreement of 1948 and Beyond

The disputes and negotiations surrounding piecework and time-motion studies in the 1940s resulted in the national Work Studies Agreement between LO and SAF signed in 1948. By the end of World War II, time-motion studies, as an essential rationalization method, were widespread in Sweden. Thus, resolving the rationalization issue at a national level became essential for both workers and employers. The agreement was based on a deal between the MWU and the MTEA reached after the metal workers’ strike. Subsequently, the LO acquired the right to centrally negotiate disputes related to work studies and rationalization. The agreement also mandated that the LO promote work studies as fundamental to industrial rationalization. Similar to the agreement between the MWU and the MTEA, the national agreement formed a joint Work Studies Council, whose primary role was to promote further collaboration between the LO and the SAF in rationalization efforts.

The Work Studies Agreement and the Work Studies Council were commonly known as the Rationalization Agreement and the Rationalization Council respectively, pointing to the intertwined connection between scientific management and rationalization. One of the Council's main objectives was to increase support for time-motion studies and rationalization among Swedish workers. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Council produced a series of literature that emphasized the importance of rationalization, for example Work Studies in Collaboration (Arbetsstudier i samverkan) published in 1950 and Rationalization for the Common Good (Rationalisering till gemensam nytta) published in 1966. However, the Work Studies Agreement was controversial among LO members. Representatives from several unions, including the MWU, argued that disputes on the shop floors could not be resolved by a central agreement. Disagreements regarding time-motion studies on the shop floors were best resolved through measures that encouraged local cooperation.Footnote 75 Nevertheless, the LO called the agreement a “new Saltsjöbaden Agreement” and described it as an important victory for workers and the Swedish labour market.Footnote 76

Although the workers in the association expressed some disappointment with the MWU's decision to call off the strike in 1945, the association's conferences in the following years were relatively positive about the newly established company councils. Cooperation with management had, in some cases, led to somewhat better relations and working conditions, although not everyone agreed.Footnote 77 Yet, frustration with time-motion studies and piecework endured both within and outside the association after 1948. Nevertheless, the new agreements signed by both the MWU and the LO provided new infrastructure for managing and defusing conflicts. More importantly for workers, the agreements meant that employers, at least on paper, recognized their right to influence time-motion studies and other rationalization procedures.

The agreement between the MWU and the MTEA following the strike, and in particular the agreement between the LO and the SAF on work studies, solidified the corporatist model. Paradoxically, worker resistance contributed to further centralization of industrial relations. The struggle against scientific management under the veil of rationalization failed to fundamentally change the labour process. This is a conclusion also drawn by Kevin Whitston regarding Britain.Footnote 78 Time-motion studies persisted and evolved into more advanced systems, e.g. Methods-Time Measurement (MTM). What changed was the ability of unions to regulate the extent to which employers could implement these methods. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, a wave of wildcat strikes challenged the institutional framework for rationalization in Sweden. An internal MWU investigation concluded in 1969 that time-motion studies and piecework were the main cause of the strikes.Footnote 79 Piecework was finally abandoned in the 1980s as the standard form of wage payment in Sweden, largely as a result of the strikes.Footnote 80

Conclusions

My goal has been to demonstrate how worker resistance to Taylorism affected the institutional framework of the post-war labour market in Sweden. By analysing material from workers in the Separator Corporate Group, the MWU, and the LO, this article has highlighted the interdependence among these three levels – the shop floor, the unions, and central labour market relations. These dynamics carry important implications for our understanding of how worker resistance can impact the political economy. They underscore the transformative potential of worker resistance and its capacity to steer institutional frameworks.

Although workers were discontented with scientific management, it spread throughout the Swedish metal and engineering industries during the 1930s and 1940s. This resulted in widespread disputes, which contributed to the Metal Strike of 1945, leaving significant marks on industrial relations in Sweden. Workers consistently argued that scientific management undermined their bargaining position by making knowledge about the labour process and wage setting inaccessible. Consequently, management achieved a monopoly on knowledge, which workers perceived as a game changer. The main criticism of scientific management focused on the heightened employer capacity to monitor and control workers.

Following the 1945 strike, the LO and the SAF engaged in concerted negotiations to resolve workers’ opposition to time-motion studies and rationalization. These talks ultimately led to the Work Studies Agreement of 1948, which expanded on the prior agreement between the MWU and the MTEA from 1945. By providing a platform for negotiations and instituting the Work Studies Council, this agreement encapsulated not only the response to worker resistance, but also marked a pivotal step towards a corporatist approach to rationalization. Worker resistance to time-motion studies consequently made the Swedish labour market more centralized. It also opened new channels of cooperation between labour and capital by laying the foundation for a corporatist framework for rationalization.

Arguably, the formative years of the 1940s witnessed the integration of “soft” Taylorism, characterized by the technocratic social organization of production, into Swedish labour market policy. Efforts to bring trade unions and employers closer together through a shared rationalization policy had been attempted long before the 1948 agreement. In the Industrial Peace Conference of 1928 and during the negotiations that resulted in the Saltsjöbaden Agreement in 1938, rationalization and industrial peace were central discussion points. The specific form of cooperation, however, crystallized after a series of agreements in the 1940s. Considering the strong trade union movement in Sweden, as well as in many other Western countries, employers inevitably relied on the active involvement of trade unions in the rationalization efforts. Worker resistance was thus unable to fundamentally change the organization of work. Although their resistance did not lead to the complete abandonment of Taylorist rationalization, it did result in its regulation within the confines of Swedish corporatism.

Although this article has concentrated on the historical events in Sweden, it underscores the complex interactions between worker agency and the political economy in general. It offers us insight into the malleability of Taylorism and how worker resistance can influence institutional frameworks.

As previously emphasized, Sweden's experience was not unique. Similar transformative changes in production processes and industrial relations occurred in many industrialized (and semi-industrialized) capitalist countries. These conclusions extend beyond the scope of the Swedish case, highlighting their relevance to a wider global context. Consequently, they invite further research into the dynamic interplay between local trade union activism and central industrial relations, which have exerted a significant influence on the formation of labour market structures.