I. Introduction to LNGS in 5G/IOT Markets

Standard-Essential Patent (SEP)-enabled cellular standards have experienced a large degree of market success. In 2016, the number of cellular subscriptions exceeded the world population.Footnote 1 In 2020, the mobile industry’s contribution to world GDP was estimated at $4.4 trillion.Footnote 2 By 2035, the impact of 5G is predicted to grow to $13.2 trillion in gross output worldwide.Footnote 3 However, while the total estimated revenue from cellular SEP licensing is less than one half percent of the size of the mobile economy,Footnote 4 the market for SEP licensing has remained contentious with both SEP licensees and licensors claiming inefficiencies, characterized as patent holdup and holdout, respectively.

In response to concerns that inefficiencies in SEP licensing may have a negative systemic impact on the development of emerging 5G and Internet of Things (IoT) markets, the European Commission (EC) convened an Expert Group on Licensing and Valuation of Standard Essential Patents (SEP Expert Group), resulting in a report including 79 proposals aimed at improving the SEP licensing market.Footnote 5 This chapter is focused on Proposal 75 – Licensing Negotiation Groups (LNGs), which was formulated by an individual member of the SEP Expert Group. The goal is not to critique the specifics of Proposal 75 but to take the general concept of an LNG and formulate a specific institutional and organizational design.

The concept of LNGs or similar collective buying arrangements has been proposed previously in the context of Standard Development Organizations (SDOs) as a means to counteract the perceived market power of SEP holders and reduce the risk of patent holdup and royalty stacking.Footnote 6 Ironically, we hypothesize the opposite, that the main social benefit of LNGs is the potential reduction of transaction costs and patent holdout. This is not only because patent holdup and royalty stacking have never been empirically proven to have a systemic impact in SEP-enabled markets,Footnote 7 but that the most likely challenge of SEP licensing in IoT is overcoming the collective action problem among a large number of similarly situated SEP implementers.Footnote 8

The deployment of 5G/IoT is expected to result in a large increase in SEP implementers across diverse industries. Similarly situated SEP implementers are market actors competing against one another through prices in the product market, so SEP royalties are seen as an input cost. While these IoT-based SEP implementers are all incentivized to reduce input costs (that is, SEP royalty rates), no implementer is incentivized to take a license at all if they are not assured that all other competing firms will also take a license on comparable terms. Thus, even if an agreement on the standard of a “Fair, Reasonable, and Nondiscriminatory” (FRAND) rate can be achieved,Footnote 9 there is a rational, systemic disincentive by SEP implementers (that is, a collective action problem) to take an independent license, which facilitates patent holdout. This challenge is fundamentally different from the simple reduction of transaction costs that accompanies the elimination of redundant bilateral negotiations through collective action, though these savings can also be substantial, as shown in Figure 7.1. Concomitantly, a large reduction in transaction costs could facilitate the licensing of more SEP implementers, especially those in the long tail that have traditionally been able to hold out due to their small size.Footnote 10

Figure 7.1. Theoretical transaction cost reduction through pooling both sellers and buyers.

S, Seller; B, Buyer; SP, Seller Pool; BP, Buyer Pool.

The desired gains of LNGs are not without the possibility of potential negative consequences. For example, a frequently used argument against LNGs is that they run a high risk of becoming a buyer’s cartel, where the members collude to agree to pay a maximum royalty well below the FRAND rate, which would not give a SEP holder a reasonable reward for its contributions to a standard and reduce incentives to participate in standardization. Similarly, it is postulated that LNGs could facilitate a collective holdout strategy with the goal to ultimately pay lower than FRAND royalties or no royalties at all.Footnote 11 Furthermore, the anticompetitive risks of LNGs have been said to be too great in relation to their potential reduction of transaction costs, which can more effectively be managed through existing patent pool models.Footnote 12

While it is correct that these risks internal to an LNG may exist, that should not be a reason to simply reject the concept of LNGs as an undertaking that is anticompetitive per se. In this respect, a parallel with patent pools can be drawn, since analogous arguments can be made against patent pools, which could facilitate the formation of a seller’s cartel to capture supra-FRAND royalties (that is, a collective patent holdup strategy).Footnote 13

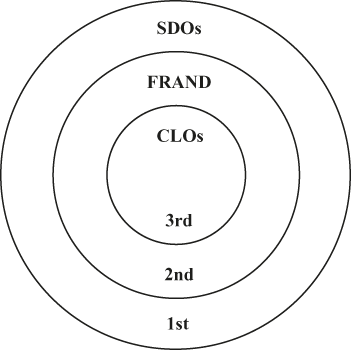

It is also important to acknowledge that both patent pools and LNGs, as well as other collective licensing organizations (CLOs), are part of a broader multilayered, open innovation ecosystem of privately ordered market governance.Footnote 14 The first layer of collective action includes the open, consensus standardization process of SDOs, which is widely accepted as pro-competitive. The second layer of collective action includes the FRAND-based intellectual property (IP) policies that incentivize (1) investment in upstream R&D and contribution of technology, and (2) investment in the production and distribution of standard-enabled products and services. As both these investments are sunk costs, the FRAND commitment is a critical mechanism necessary to balance the interests and reduce the overall financial risks shared between SEP holders and implementers. Therefore, CLOs are born within this already highly collaborative ecosystem of vertical and horizontal competitors, operating as a third-order means of collective action to solve the remaining SEP licensing challenges emanating from the expansion of connectivity into new IoT markets. Figure 7.2 illustrates the levels of collective action in which the norms of LNGs are embedded and through which the norms of antitrust must be interpreted.

Figure 7.2. Multilayered collective action in SEP-enabled standardized markets

The historically developed norms of collective action within the cellular ecosystem have incentivized private firms to invest tens of billions of dollars in fundamental cellular R&D and contribute millions of person-hours in joint standard development, which has resulted in open standards implemented across industries that have enabled trillions of dollars of economic impact.Footnote 15 Creating a Pareto improvement to this ecosystem is a humbling task given the complex interaction of increasing technological functionality, expanding industry use-cases, and converging market norms. The remaining sections of this chapter are a first attempt to design an LNG that increases the efficiency of SEP licensing for both licensors and licensees while reducing the relevant antitrust risks.

The structure of the chapter is the following. Section II describes the general antitrust treatment of seller and buyer collaborations and then focuses on specific antitrust concerns and safe harbors related to collective action in the SEP licensing context. Section III describes the Huawei v. ZTE licensing framework and how it may apply to LNGs. Section IV discusses how LNGs could be implemented in compliance with antitrust safeguards, sketches the internal governance rules of LNGs, and provides some examples from practice where collective implementer groups were used to facilitate SEP licensing.

II. Antitrust, Collective Action, and SEP Licensing

A. General Antitrust Principles for Collective Action among Competitors

Antitrust laws have been traditionally suspicious about collaborations among competitors. Two main concerns are associated with competitor collaborations. The first is that cooperation may result in a cartel, where companies would discuss and exchange sensitive commercial information and agree on prices, output, quality, or innovation.Footnote 16 The second concern is that collaboration among competitors may increase collective market power and harm competition by increasing the ability and incentive of companies to raise prices above competitive levels or reduce output.

On the other hand, in some instances, cooperation among competitors may lead to pro-competitive benefits. Competitor collaboration may enable companies to offer new or cheaper products or services. The key is the combination of complementary activities, skills, or assets.Footnote 17 For instance, companies may combine their complementary research and development activities to produce new and improved products or combine complementary assets and skills to achieve economies of scale or scope. In contrast, the combination of substitutes will normally raise antitrust concerns.Footnote 18

Competitor collaborations are regulated by special antitrust guidelines of the European Commission in the European Union and the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the United States. Guidelines provide a general “safe harbor” or “safety zone” for agreements that are not hidden cartels and do not exceed a certain market share threshold. In the United States, a safety zone is established for such agreements among competitors, which do not collectively constitute more than 20% of the relevant market,Footnote 19 while in the European Union, the collective market share threshold is 15%.Footnote 20 Additionally, there are special rules for assessing specific types of competitor collaborations, such as joint research and development, specialization, production, purchasing, commercialization, and standardization agreements.

The same rules in principle apply to both seller and buyer collaboration. However, seller cooperation is regulated more extensively, as it may include a broad spectrum of activities from joint R&D production to joint commercialization of products or services. Buyer collaboration covers joint purchasing, enabling buyers to negotiate better terms and conditions with sellers, leading to lower prices for consumers. The negative aspects of buyer collaboration may, in contrast, be felt by consumers or purchasers. Suppose buyer collaboration results in significant buyer power. In that case, buyers may decide not to pass on lower purchase prices to final consumers or collectively reduce the purchase price below the competitive level, harming sellers and reducing their incentives to innovate and, as a result, lowering the quality or output supplied by sellers.Footnote 21

B. Collective Action and SEP Licensing

Competitor collaboration exists in relation to SEP licensing as well. To date, we have largely seen collaboration on the seller side, where SEP owners form patent pools to jointly license SEPs to third parties. Antitrust authorities have adopted specialized rules for assessing the formation of patent pools and licensing-out of SEPs from a patent pool to third parties.Footnote 22 In contrast, LNGs for implementers are a new phenomenon, and there are currently no specialized rules for their assessment. Thus, general rules on assessing horizontal joint purchasing agreements could be used by way of analogy.

Pools and joint purchasing agreements share the same antitrust concerns. The main risk is that the aggregation of substitute products or services would constitute a price-fixing cartel and amount to a “per se” restriction (US) or a restriction of competition “by object” (EU). Additionally, horizontal cooperation among sellers or buyers risks exchanging confidential business information that may lead to direct or indirect collusion and cartelization on downstream product markets and upstream technology markets. The increased market power of such horizontal cooperation is another concern, which may lead to foreclosure of alternative technologies or harm to sellers manifesting in reduced innovation and product quality. Table 7.1 summarizes antitrust-related concerns of patent pools and horizontal joint purchasing agreements.

Table 7.1. Anticompetitive concerns with pools and joint purchasing agreements

That said, antitrust authorities have produced guidelines for assessing joint purchasing agreements and have identified conditions when such competitor collaborations would not raise antitrust concerns. The rules for patent pools are much more elaborate than for joint purchasing agreements. There may be several reasons for such differentiated treatment. Joint purchasing agreements are primarily associated with the procurement of physical goods and services, while patent pools relate to the joint selling of technology (that is, intangible assets). Guidelines for joint purchasing agreements rely on market share thresholds to control the potentially negative effects of the increased market power of its members. On the other hand, patent pools are more efficient when they aggregate as much of the selling side of the market as possible. Thus, safeguards are focused not on the market share thresholds of pool members, but on mechanisms to control and negate the market power of a pool, for example, by only allowing the pooling of complementary patents, the freedom to license outside of the pool, and FRAND licensing terms for pooled patents.

Table 7.2 provides an overview of current antitrust safe harbors related to patent pools and joint purchasing agreements.

Table 7.2. Current antitrust safe harbors for pools and joint purchasing agreements

Considering that LNGs are a new phenomenon consisting of buyer collaboration in technology markets, some antitrust principles for LNGs could be borrowed both from antitrust safeguards related to joint purchasing agreements and from those related to patent pools.

III. LNGS and the HUAWEI v. ZTE Negotiation Framework

In July 2015, the European Court of Justice (CJEU) issued its opinion with respect to certain questions that the German Federal Court of Düsseldorf referred to the CJEU in a SEP infringement case between Huawei and ZTE.Footnote 23 The opinion of the CJEU clarified the conditions under which a SEP holder could seek an injunction against an infringer without violating European competition laws by abusing its dominant position by virtue of holding a SEP.

The judgment of the CJEU created the clarity desired by SEP holders, implementers, and the national courts in EU member countries. The CJEU judgment provided guidance for how SEP licensors and implementers should behave in SEP licensing negotiations. It sets out several steps that SEP licensors and implementers should follow for a SEP licensor to be considered a willing licensor and an implementer to be regarded as a willing licensee. Although it is not mandatory for a SEP licensor to follow these steps and it can demonstrate that it is a “willing licensor” in other ways, a SEP licensor following these steps can seek an injunction against an implementer who does not conform to these guidelines, without risking a violation of the competition laws.

Under the Intellectual Property Rights Policy of ETSI (ETSI IPR Policy), a leading SDO in wireless communications, a SEP holder must undertake to license its SEPs under FRAND terms to implementers of the relevant standard. A SEP holder that is not willing to license its SEPs to an implementer seeking a license would breach that undertaking in the ETSI IPR Policy. Under French contract law, which governs the ETSI IPR policy, many courts have deemed implementers as third-party beneficiaries of the FRAND commitment in the ETSI IPR Policy.Footnote 24 However, any dispute about whether terms offered by a SEP licensor are indeed FRAND is a matter that national courts should judge under their national laws.

Under the CJEU guidelines, a SEP holder seeking to license its SEPs to an implementer must, as a first step, make the implementer aware of the alleged infringement by notifying them in writing of these SEPs and the relevant infringing products. In response, the implementer must, as a second step, express its willingness to conclude a license under these SEPs on FRAND terms. If the implementer does not do so in a timely manner, it may be considered an unwilling licensee, opening up the path for a SEP holder to seek an injunction. After the implementer has indicated its willingness to enter into a FRAND license, the SEP holder must, as a third step, make an offer in writing to the implementer specifying the royalty and how they determined that royalty. In return, the implementer must, as a fourth step, diligently respond to that offer by either accepting it or promptly providing a counteroffer in writing to the SEP holder, which the implementer believes is FRAND. In making a counteroffer, the implementer must also provide security in the form of a bank guarantee or put into escrow an amount equivalent to the royalties for its past sales, if any, based on his counteroffer. The implementer must supplement this amount to reflect estimated royalties on future sales.

An important aspect to mention here is that an implementer may challenge the essentiality, validity, or infringement of the asserted SEPs during the negotiations with the SEP licensor and may even do so after concluding a license agreement.

After the CJEU published its judgment in 2015, national courts further refined the various steps of the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework in several infringement cases in the years thereafter. For example, national courts have specified the requirements for a written notice of infringement to the implementer,Footnote 25 the conditions under which an implementer is not considered to be a willing licensee,Footnote 26 and the conditions for providing security.Footnote 27 Courts have also clarified that a SEP holder must provide the reasons why it considers its proposed royalty rate to be FRAND.Footnote 28 Sometimes, different courts in the same jurisdiction reached different conclusions on the same topic.Footnote 29 Nevertheless, SEP licensors have mostly conducted licensing negotiations following the steps of the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework to safeguard the ability to seek an injunction in case an implementer does not conform to this framework. Likewise, implementers have followed the steps of the framework to avoid being considered an unwilling licensee and risking an injunction.

A. Implications for LNGs

Now turning to LNGs, various questions may be raised when considering how the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework should be applied to LNGs or, stated differently, how LNGs should conduct licensing negotiations in line with this framework. The different aspects of applying the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework to LNGs will be addressed in the remainder of this section, following the subsequent steps of the framework. For this purpose, it is assumed that the LNG has been established so that it can be considered as lawfully representing its members in any interaction with the SEP licensor.

If the SEP licensor notifies the LNG in writing of alleged infringement of its SEPs by LNG members, it seems reasonable that the SEP licensor must only specify the category of products considered to be infringing and does not have to indicate at least one specific product of each LNG member. This category of products is also what creates the common interest of the members in having this SEP licensing matter addressed through the LNG.

Another interesting aspect to consider is whether the SEP licensor is entitled to exclude one (or more) members of the LNG for purposes of resolving a particular infringement dispute, because it prefers to have bilateral negotiations with this member. This may be the case if, for example, the SEP licensor and that member have multiple overlapping business activities and the SEP licensor wants to enter into negotiations with that member covering a broader scope than the specific products for which the LNG will negotiate licenses. It may also be the case that the SEP licensor and the member already have a license agreement in place covering part of the SEPs it is offering to license to the LNG. This is the mirror situation of a scenario in which a patent pool approaches an implementer for a pool license, and the implementer prefers to have bilateral negotiations with licensors in the pool, because, for example, the implementer already has a (cross-) license agreement in place with one or more pool licensors and covering the products licensed by the pool. A licensor cannot refuse to enter into bilateral license negotiations with an implementer that makes such a request. Following the same approach for LNGs, an LNG member should not be allowed to refuse a request for bilateral negotiations from a SEP licensor.

In response to the written notification of the SEP licensor, the LNG must communicate that its members are willing to enter into a license agreement on FRAND terms with the SEP holder. This willingness should be unconditional in the sense that this willingness should not depend on whether, and the extent to which, individual members accept the outcome of the negotiations between the LNG and the SEP licensor. Negotiations between a SEP licensor and an LNG are likely to fail without a firm commitment by members of the LNG to accept the outcome of the negotiations and enter into a license agreement with the SEP licensor on that basis. Suppose the LNG and the SEP licensors reach an agreement on the FRAND terms of a license, and the LNG members are free to accept or decline this outcome and thus can freely determine whether or not to enter into a license agreement on these terms with the SEP holder. In that case, the SEP holder may find it unattractive to enter into license negotiations with the LNG at all. It will create an incentive for at least some LNG members to request bilateral negotiations with the SEP licensor and take the outcome of the negotiations with the LNG as the starting point for their own bilateral negotiations, hoping to negotiate separately even better licensing terms. The freedom to decline the agreed outcome of the negotiations between the SEP holder and the LNG may also be used as part of a holdout strategy by an implementer, who can defer paying royalties that licensed LNG members are already paying. Members should commit to entering into a license agreement with the SEP holder if the LNG and the SEP holder have reached an agreement approved by the members. This aspect will be addressed in greater detail when discussing the governance of LNGs in Section IV.

A key factor in the success of LNGs relies on members’ commitment to enter into a license agreement with the SEP licensor based on the approved outcome of negotiations between the LNG and the SEP licensor. Suppose, despite such a commitment, a particular member does not enter into a license agreement with the licensor within a reasonable period after the agreement is reached. In that case, it seems reasonable that this member should be deemed an unwilling licensee and the licensor should be entitled to seek an injunction against the implementer without being accused of misusing a dominant position. If the SEP holder initiates litigation against a recalcitrant LNG member and the member, in the face of a likely injunction, elects to accept the FRAND terms negotiated with the LNG, it seems unfair that the implementer would still be entitled to a license under the same FRAND terms. Even if a court finds that the implementer is still entitled to a FRAND license, the implementer should be required to pay a penalty on top of the agreed FRAND terms (for example, in the form of a higher royalty for infringing sales made prior to entering into the license agreement with the SEP licensor).

Suppose a SEP licensor submits a FRAND license offer specifying the royalty and giving the reasons why it considers this royalty to be FRAND. In that case, the LNG must diligently respond to that offer without undue delay. If the LNG does not accept the license offer, it should timely make a FRAND counteroffer in writing. In bilateral negotiations, courts have held that a response time of three months is not timely.Footnote 30 In contrast, in another case, a five-month period was not regarded as timely.Footnote 31 In the case of LNGs, courts may take into consideration that it may take more time for the members of an LNG to agree internally and deliver a counteroffer, but even in this case, a court may find that making a counteroffer after more than five months is not timely.

If that situation would arise, would all LNG members be considered unwilling licensees? It is difficult to predict how a court would determine this point. Nonetheless, the mere fact that an LNG is negotiating with a SEP licensor does not release that LNG from its obligation to provide a timely FRAND counteroffer after having rejected a licensor’s offer. Additionally, there may be a different response time that a licensor is willing to accept before taking legal action. The SEP licensor may prefer the prospect of getting all members of an LNG licensed through a single negotiation over litigation, and may therefore be willing to accept a longer period for the LNG to respond to its FRAND offer than would be the case in a bilateral negotiation.

The same question arises if, in response to an offer by a SEP licensor, the LNG responds with a very low counteroffer that is clearly non-FRAND. Will all LNG members be considered unwilling licensees and potentially risk an injunction if the SEP licensor commences infringement actions against individual LNG members? In this case, all LNG members should again be considered unwilling licensees. Under the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework, a group of licensees should not behave and be treated differently than any individual licensee.

Moreover, suppose the LNG does not negotiate in good faith by a delayed response to the SEP holder’s offer and then making a clear non-FRAND counteroffer. In that case, the SEP licensor may accuse the LNG members of engaging in a group holdout, which may be the basis for an antitrust complaint by the SEP licensor.

Under the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework, if the SEP licensor rejects a counteroffer from an implementer, the implementer must provide a bank guarantee or put in escrow an amount for the royalties on its past sales based on the rate in its counteroffer. Applied to the LNG context, this implies that the LNG must provide a collective bank guarantee for all its members or put an amount in escrow for the royalties on the collective past sales of all its members, or alternatively, each individual member would have to provide a bank guarantee or put money into an escrow account for the royalties on its past sales. In both cases, the members would have to provide an accounting of these past sales. In the first case, it may be difficult for the LNG to get a bank guarantee, since it may not have funds to support this guarantee, and it will not be an easy task to ensure that all members place the appropriate amounts in escrow.

In negotiating a SEP license, an LNG must follow the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework in the same manner as an individual company. In theory, since LNGs are likely formed with the goal of reducing transaction costs for their members, to negotiate better FRAND royalty terms than each individual member could negotiate, and to level the playing field among their members, they should be incentivized to negotiate in good faith, especially if its behavior could result in all its members being deemed unwilling licensees, which would entitle the SEP holder to seek injunctive relief against LNG members. This accountability should also encourage the LNG to timely respond to written notifications (infringement letters and/or FRAND offers).

IV. Implementation of LNGs

A. A Safe Harbor for LNGs

As discussed in Section II.B, a set of guidelines similar to those that have been developed for patent pools is needed to create a safe harbor for LNGs. Currently, no request for review of an LNG for licensing purposes has been submitted to the DOJ or EC (or other competition authority). Nevertheless, it is possible to identify a number of conditions that LNGs must satisfy to avoid likely conflicts with antitrust laws.

One key question is whether the members of an LNG should be allowed to have a collective market share that could enable the LNG to exercise market power. Generally, a collective market share of less than 15–20% is considered acceptable in the case of other types of collaborative buying groups.Footnote 32 However, greater market shares may be deemed pro-competitive given the potential to reduce transaction costs and limit patent holdout, especially as the LNG is bound to a FRAND rate and, in Europe, the negotiation guidelines of Huawei–ZTE. However, as the market share of an LNG increases, additional antitrust scrutiny is justified, concerning both the SEP licensing market and the possibility for collusion among LNG members in the downstream product market. Thus, it will likely be necessary to assess the maximum collective market share for LNGs on a case-by-case basis across different industry verticals. Taking the smartphone market as an example, an LNG including Apple, Samsung, Xiaomi, Oppo, and Vivo with roughly a 70% collective market share would be heavily scrutinized. On the other hand, companies in the tail of the smartphone market, each of which has less than a few percent market share, should be allowed to form an LNG without significant inquiry, since they do not have a strong market position, do not collectively hold significant market power, and the LNG will have better negotiation capabilities than each individual member. If successful, the LNG will not harm competition or innovation in the smartphone market.

LNGs will tend to be more successful if members are situated at approximately the same level of the value chain. In the example just discussed earlier, the smaller companies in the tail of the market are all similarly situated. This would likely help solve the collective action problem (that is, patent holdout) introduced in Section I by facilitating a level playing field among similarly situated competitors. It would be more difficult if the LNG has members operating at different levels in a value chain that make and sell different products (components versus end products). In that situation, conflicting interests among LNG members may make it unattractive for a SEP licensor to start licensing discussions with the LNG.

LNG members could be allowed to share information within the group about the essentiality, validity, and infringement of the relevant SEPs. However, they should not share any opinions or conclusions regarding this information, as this may be considered collusion. On the other hand, the LNG could be allowed to act on behalf of its members by seeking outside counsel’s opinion regarding certain matters, since this would likely reduce the costs borne by each member, consistent with a key purpose of an LNG.

During their meetings, LNG members should not be allowed to discuss prices of products, profit margins, or market shares. The same principle applies in meetings of SEP licensors in the context of patent pools. To ensure that this rule is upheld, it would be advisable for an antitrust lawyer to attend all their meetings and remind the participants at the start of each meeting about the members’ duties to operate in accordance with the antitrust laws and about the subjects they must not discuss. This external counsel should also intervene if any member raises a topic that should not be addressed.

LNG members should be allowed to disclose their position on royalty rates only with the LNG representative negotiating with the SEP licensor and not between LNG members themselves. This alleviates the concerns about possible coordination of royalties by LNG members, as only the LNG negotiator will have all the information on royalties collected from members. And only the LNG negotiator needs to know the pricing position of all LNG members in order to attempt to arrive at the most acceptable royalty level in negotiations with SEP owners.

Moreover, it should be realized that the LNG and the SEP licensor are bound by the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework, which reduces the risk that the LNG will be able to negotiate or dictate a sub-FRAND royalty. Concluding licenses with a group of companies in a single negotiation through an LNG reduces the cost of licensing for a SEP licensor. The SEP licensor may share part of these benefits with the LNG members by accepting a lower royalty, but in doing so, the SEP licensor will still have to consider the nondiscrimination prong of its FRAND obligations toward other similarly situated licensees outside the LNG.

These proposed steps for conducting negotiations between SEP licensors and LNGs and other pertinent steps should be formulated into guidelines that aim to create a safe harbor for LNGs and which, if followed, would greatly reduce the most problematic anticompetitive risks. As mentioned, LNGs seem particularly interesting for similarly situated companies in the tail of markets, which collectively do not possess a market share that gives them market power. Given the increasing use of connectivity standards in various IoT verticals and the increasing number of companies that require licenses under SEPs from licensors for these standards for a wide variety of products, LNGs become increasingly attractive for both SEP licensors and similarly situated implementers given lower transaction costs and the opportunity for smaller implementers to secure more competitive royalty rates and enter the product market on a level playing field. This is even more relevant, as implementers in emerging IoT verticals may be less familiar with standards and SEP licensing than implementers in the telecom sector.

B. Governance of LNGs

In the previous sections, the organization, operation, and decision-making of an LNG have not been addressed. However, the governance of an LNG is one of the decisive elements in determining its success. Member selection, member commitments to enter into license agreements with a SEP licensor(s) on agreed terms, voting rules, and providing clear mandates for the negotiators are principal elements that must be included in the governance of LNGs. This section will describe the various governance elements of an LNG in more detail.

An LNG can be set up in different ways, from purely formal to informal. LNG members can establish a legal entity specifically for this purpose, which is jointly controlled by the members. This may be attractive in a setting where the members are already members of a professional organization or association in their industry and where they will use this entity for handling negotiations with other SEP licensors for the same and other standards that they may use in their products. They can hire one or more licensing experts and other staff required to do the actual negotiations with a SEP licensor. The LNG members need to agree among themselves and with the legal licensing entity what mandate is given to the licensing entity and how that entity should interact with the LNG members.

Alternatively, the LNG members could simply contract several experts or a law firm to handle the negotiations on behalf of the LNG members on a project basis. In this case, the relationship between LNG members and the contractor must be formalized so that the negotiators have a clear mandate. In a more loosely controlled arrangement, the members of an LNG could elect a number of their representatives as the negotiators on behalf of the members and potentially hire a law firm or licensing experts to support them in the negotiations with the SEP licensor. Whatever the setup of the actual group or entity for handling the negotiations, it is important that negotiators have a clear mandate from the LNG. In particular, the process of communicating with the LNG during the negotiations should be clear and fully transparent, as it may otherwise frustrate not only the relationship between the LNG entity and LNG members but also the relationship between the entity and the SEP licensor(s).

When handling a specific SEP licensing opportunity, relevant companies need to determine individually whether they want to become members of the LNG or wish to opt out, because they prefer to negotiate with the relevant SEP licensor(s) bilaterally. As discussed in Section III, giving members the opportunity to opt out once the results of the LNG negotiations are known incentivizes individual members to use the outcome of the negotiations as a starting point for separate bilateral negotiations, aiming to get a better deal for themselves. This could lead to a disparity in royalty rates among LNG members. As a member of an LNG, a company enjoys the benefits of lowering its transaction costs and potentially obtaining better FRAND terms than it would be able to negotiate itself. However, it also runs a risk that it will not be satisfied with the terms negotiated with the SEP licensor and approved by the LNG members. Each company should assess this risk and determine whether it wants to opt out at the beginning of the negotiations with the SEP licensor. Also, allowing LNG members to opt out at the end of the process could induce certain implementers to hold out as long as possible based on the expectation that the SEP licensor may not be willing to litigate against an individual member, since the litigation cost may be higher than the revenues that can be collected from that implementer. Therefore, to prevent use of the LNG as a vehicle for holdout, the LNG should at the start of the process request that members commit to the agreed outcome of the negotiations and enter into a license with the SEP licensor within a predetermined period after approval of the result of the negotiations. In this way, SEP implementers can either negotiate collectively in good faith or opt out from the beginning, where the latter is simply the status quo.

Suppose an LNG would include companies that operate at different levels of a value chain, for example, members who operate at the downstream end product level and other members who operate at the component level. In that case, the LNG should be formed only by members operating at the same level in the value chain. The appropriate membership for the LNG will depend on the level in the value chain that the SEP holder targets for its licensing program. This should be clear from the assertion letter from the SEP licensor, in which it should indicate the devices alleged to infringe its SEPs. If LNG members occupy different levels of the value chain, the likelihood of a successful outcome to the negotiations is lower.

LNG members will also need to conclude a nondisclosure agreement to keep the information regarding the negotiations confidential and not disclose it to others both inside or outside the LNG. It is recommended that the LNG involves an outside counsel who can advise the LNG members on the obligations of the LNG to operate in line with the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework and also to remind members at every meeting that members should not discuss prices, profits, market shares, and other information that would run afoul of antitrust guidelines. Moreover, this counsel should guide the members on what types of information they can share concerning the essentiality, validity, and infringement of the SEPs asserted by the licensor. Again, the goal is to reduce transaction costs while managing the risk of antitrust behavior.

Another important governance aspect of an LNG is how decisions are taken and thus what voting rules and procedures are put in place for various categories of topics that the LNG members may have to decide upon. Requiring full consensus is not recommended, as this gives individual members a veto right to block important proposals that are acceptable to all other members. Voting by a supermajority on major issues may provide a better approach for LNGs to facilitate broad market impact in the shortest timeframe (that is, reducing patent holdout).

Once the SEP licensor has provided the LNG with its FRAND offer, the LNG members will need to conduct a consultative process with their representatives concerning the terms of the counteroffer to the licensor. This will require taking into account all information regarding the licensor’s SEP portfolio, including any opinions from outside counsel. The negotiators must be given clear, approved instructions (in accordance with the voting rules) about the counteroffer and a clear mandate for the subsequent negotiations with the SEP licensor that may ensue.

Suppose the negotiators can reach an agreement with the SEP licensor about the FRAND terms for a SEP license, and the LNG members approve the results according to their voting rules. In that case, each LNG member should enter into a license agreement with the SEP licensor within a predetermined time (for example, within six months in accordance with their commitment at the start of the process). It is in the interest of all LNG members that every member honors its licensing commitment, which creates a level playing field among the LNG members and avoids the collective action problem that can induce patent holdout. Any LNG who fails to enter into a license on a timely basis may be deemed an unwilling licensee and is therefore running the risk that the SEP licensor may seek an injunction against that member. This incentive structure is critical to maintaining the level of accountability and commitment required to make an LNG a viable SEP licensing mechanism.

Having a clear and transparent governance structure will enhance the ability of an LNG to achieve its goals of reducing members’ transaction costs and obtaining better FRAND licensing terms than each member can negotiate individually. Additionally, implementing proper rules of governance can ensure that LNG members act in good faith toward both licensors and LNG members and, as a result, overcome the collective action problem that can result in systemic holdout.

C. Example of an LNG

Although LNGs exist in other fields, such as joint purchasing groups for physical goods, LNGs in the field of licensing are mostly uncharted waters, although some precursor organizations and activities do exist. For example, defensive aggregators, such as RPX and AST, aggregate buyers of patents to facilitate licensing and reduce transaction costs, which is somewhat similar to the proposed role of LNGs. The recent syndication deal between RPX and Sisvel regarding SEPs for the Wi-Fi standard illustrates the transaction cost savings obtained by “pooling” both buyers and sellers in a single transaction as shown earlier in Figure 7.1.Footnote 33 Additionally, patent licensing platforms such as Avanci exemplify how linking licensors and licensees through a single platform can potentially enhance the efficiency of SEP licensing markets.Footnote 34 One-Blue is possibly the best example of a successful negotiation between groups of SEP licensors and licensees. In this section, the experience with an actual LNG in the One-Blue context will be discussed further.

The SEP licensor, in this case, was the One-Blue patent pool, which included a large majority of all the licensors holding SEPs for the Blu-ray standard and holding a significant part of the relevant SEPs for the standard for Blu-ray Disc™ products.Footnote 35 The Blu-ray standard is the successor to the DVD standard, offering consumers higher video quality with interactive features. Blu-ray players and recorders are backward-compatible with the various DVD and CD playback and recordable/rewritable standards. For the previous standards, joint licensing programs had been formed on a standard-by-standard basis, which required securing licenses from one or more patent pools, as well as from several individual licensors. Had this approach been followed for the Blu-ray Disc standards, the number of licenses necessary to manufacture and sell Blu-ray Disc players and recorders would have been so large that it would have discouraged manufacturers from developing Blu-ray-compatible products. To promote widespread use of this standard, the three originators of this standard, Philips, Sony, and Panasonic, developed the concept of a product pool or “pool of pools” for Blu-ray products, where all the SEPs for the Blu-ray standards and the backward-compatible standards were included in one licensing package offered to potential licensees. This provided a one-stop-shop licensing mechanism that yielded a reduced aggregate royalty rate compared to the sum of the royalties that would have been paid if each standard had been licensed separately.

Based on experiences in licensing older-generation formats, it was known that licensing manufacturers in one particular major country had taken longer and had required more efforts than in many other countries. Since the purpose was to stimulate and develop the market for Blu-ray products as quickly as possible, a different approach was chosen. While the basic framework of the patent pool and its licensing program were being established, licensing discussions were commenced with the industry association in that country for the relevant type of consumer audio/video products. All the relevant manufacturers were members of this industry association. Several meetings were held, in which the basics, including the royalty structure of the new licensing concept, were explained, questions were answered, and feedback on the various elements of the licensing program was sought, which were taken into account in finalizing the patent pool program.

After announcing the patent pool licensing program, meetings between the patent pool administrator and the industry association representing their member companies continued to discuss the collective licensing of these companies. Multiple meetings took place to discuss the benefits of reduced transaction costs for these members, including the elimination of the risk of ending up in costly litigation, the prospect of ensuring a level playing field among the association members, and the efforts that the pool would undertake to license other implementers of the Blu-ray standard. This holistic value proposition incentivized the industry association to agree with the patent pool administrator to advise their relevant members to sign a standard license agreement with the pool. To incentivize members to sign up with the patent pool within a six-month period, the industry association also agreed that any member not signing up in this period would not be given access to certain additional services provided by the association as long as they remained unlicensed.

Due to the close and constructive cooperation between the industry association acting as the representative of the relevant group of manufacturers (that is, as an LNG), it was possible for the patent pool to sign up a group of 15 midsize manufacturers within six months. Achieving the same result conventionally through bilateral negotiations may have taken years and required one or more litigations. This example demonstrates that licensing groups of implementers in a single licensing negotiation process through an LNG can offer significant benefits to both SEP licensors and implementers, not only reducing transaction costs but also eliminating holdout through collective action.

V. Conclusion

Using a combined set of legal, economic, and managerial tools, LNGs can be designed to accomplish many different tasks. These tools include (1) proper guidelines to create a safe harbor, in which LNGs can operate without risking antitrust liability, (2) appropriate governance of LNGs’ internal operations, and (3) conducting negotiations between LNGs and SEP licensors in accordance with the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework for SEP licensing. Through careful institutional design, LNGs can facilitate SEP licensing efficiencies through reduced transaction costs for both licensees and licensors. Moreover, LNGs can create a level playing field among similarly situated implementers, who, as direct competitors, are rationally unwilling to take a license until everyone is licensed. LNGs can potentially solve this collective action problem and reduce the threat of patent holdout, which in turn could increase the leverage toward unlicensed companies in a virtuous cycle. Although it remains an empirical question whether LNGs can be designed to address antitrust concerns and then successfully implemented to facilitate increased SEP licensing on FRAND terms and at lower transaction costs, the substantial benefits LNGs may create for both SEP licensors and implementers make them worthwhile to explore.

I. Standardization and Standard Essential Patents (SEPs)

We may not always realize that we live in a world where standardized devices and services are ubiquitous. We use them both professionally and privately, and our activities would largely come to a halt if these devices and services would not be available. Many high-volume products and services use one or more standardized technologies. Products like PCs, TV sets, DVD/Blu-ray Disc players, and streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime use various audio and video compression standards, and smartphones, probably the highest-selling tech device of all time, use several connectivity and audio and video compression standards.

The market success of these products is to a large extent determined by the interoperability that standards provide between products and systems of different suppliers, ensuring customers that they can buy and use products from different vendors, that all will operate in the same way in combination with other parts of the system, and that consumers can enjoy the same services on products from different vendors. A person can use their smartphone, tablet, or laptop of whatever brand to view content on the networks of different operators.

Standardization can be considered as one of the most successful examples of precompetitive open innovation, where commercial entities of different sizes, research institutes, universities, nonprofit organizations, and government bodies collaborate in standards developing organizations (SDOs) or ad hoc consortia to create technical standards that meet the needs of the market in a specific domain. Participants invest in the development of relevant technologies to which they are willing to contribute and from which the best technical solutions are selected to be incorporated into the standard. The SDOs (and consortia) set these standards with the aim to have them used as widely as possible.

Entities participating in standard-setting and making technical contributions often file patents on inventive elements in their proposals. When these proposals are adopted into the standard, these patents may become standard-essential patents (SEPs), which are necessarily infringed when implementing a standard. Participants need to be incentivized to invest in research and development to develop the technologies and contribute these to standards so SDOs can develop the best possible standards from a technical perspective on a continuing basis. Licensing their SEPs to implementers of standards provides technology contributors with such an incentive. SDOs have developed intellectual property rights (IP rights) policies for how to deal with SEPs. These policies seek to balance, on the one hand, the interest of SDOs in stimulating the widespread use of standards, and on the other hand, the interest of technology contributors in securing an appropriate return for making their technologies available for incorporation into standards.

The standards likely to be most widely used in the broad field of Internet of Things (IoT) are cellular standards (3G, 4G, 5G) developed by the 3GPP,Footnote 1 a partnership of seven SDOs, and a number of different wireless standards, including Wi-Fi standards developed by IEEE,Footnote 2 and a number of standards developed by ad hoc standard groupings, including the Zigbee, Lora, and Bluetooth standards. In this chapter, we will focus on cellular standards, for which the SEPs are governed by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) IP Rights Policy.

Under this policy, ETSI members participating in the standard-setting process have an obligation to disclose in a timely manner any patent or patent application that may be or may become essential to a standard. ETSI maintains a publicly accessible database of these declared SEPs. Also, the members holding SEPs for a standard have to be willing to license under fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory (FRAND) terms to third parties interested in implementing that standard. The ETSI IP Rights Policy does not provide any further information about what FRAND means, and ETSI does not want to become involved in any commercial discussions. They leave it to SEP licensors and implementers to negotiate an acceptable FRAND royalty.

II. SEP Licensing Challenges

If SEP licensors and implementers do not succeed in negotiating a license, they have to turn to courts or arbitration to get a decision on their dispute. In the last 15 years, we have seen many SEP litigations relating to smartphones. In the period 2010–2015, litigation was used as a weapon in the platform battle between the mobile phone operating systems, Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android, which ended after Apple and Google entered into a patent truce in 2014. Most other litigation should just be seen as financial disputes between the various parties, where the SEP holder could be a commercial entity or a licensing company. Originally most cases were in the United States but over time also increasingly in Europe, in particular Germany and the United Kingdom, and more recently also increasingly in China. Litigation is initiated by both SEP licensors and implementers, in most cases because the parties could not come to an agreement on the royalty rate. To support their case, implementers mostly argue that the asserted SEPs are not truly essential, not infringed, or invalid and that the royalty offered is non-FRAND, whereas SEP holders argue the opposite.

In 2015, the Court of Justice of the European Union introduced the Huawei–ZTE negotiation frameworkFootnote 3 that provided guidance for SEP licensors and implementers on how to behave during licensing negotiations. A SEP licensor can seek an injunction against an implementer that is an unwilling licensee without violating competition laws, and implementers can show that they are a willing licensee and avoid an injunction if they follow the relevant steps of this framework. Although parties negotiating SEP licenses generally follow this framework, it has not led to a significant reduction in SEP litigation. Since the introduction of the Huawei–ZTE framework in 2015, more than 65 court cases have been decided in European countries, including more than 40 in Germany alone.Footnote 4

Courts in various countries, and also the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB),Footnote 5 in the United States hold SEPs invalid or partly invalid in a majority of the cases where validity is challenged. Generally, willing implementers face little risk of an injunction when challenging essentiality, validity, and royalties as non-FRAND, because even if they are unsuccessful in litigation, they will still likely wind up paying only a FRAND royalty. Moreover, implementers might benefit from a hold-out or delaying strategy since SEP holders are often willing to give discounts on past sales when negotiating a license retrospectively. The longer the past sales period, often the higher the benefit from such discounts.

Given this situation, SEP litigation rates are unlikely to decline in the years to come. To the contrary, due to the increasing use of connectivity standards in the various IoT verticals, the number of companies having to take SEP licenses for these standards for widely different products will rapidly grow, and the same is likely to be true of SEP litigation. Companies in these IoT verticals may be less familiar with standards and SEP licensing, which may create additional difficulties in SEP licensing. The European Commission (EC) has recognized that this may slow down the development of digital and sustainable technologies and related markets in Europe. As announced in its 2020 IP Action Plan,Footnote 6 the EC is considering steps to create a more transparent and predictable SEP licensing ecosystem. Realizing that SEP licensing is frequently done at a global level, the EC will promote its SEP licensing principles to, and cooperate with, other countries and regions, including Japan and the United States.

The EC will focus on three policy pillars to introduce new regulations or guidelines: (i) enhancing transparency on SEPs; (ii) providing clarity on various aspects of FRAND; and (iii) improving the effectiveness and efficiency of enforcement. Since this is still a work in progress, it is not known yet which specific measures the EC will take. (This discussion was finalized prior to, and therefore does not address, the EC’s announcement of new proposed SEP regulations in April 2023.) However, we believe that creating a smoother and more efficient SEP licensing system leading to less litigation requires a holistic approach that considers all elements of the SEP licensing process that trigger litigation or are mostly used in litigation to secure royalty terms that are more favorable than the SEP licensor is offering or than the implementer is willing to accept. By addressing only some elements, parties in SEP negotiations will likely focus on other elements to get better financial terms, and these elements may again be triggers of litigation.

In the end-to-end licensing process, we think that five elements are the main reasons for disputes and litigation in SEP licensing negotiations: (i) lack of SEP transparency;Footnote 7 (ii) low confidence in the validity of SEPs; (iii) inability to assess a reasonable aggregate royalty; (iv) lack of incentives to seek licenses; and (v) concerns about an unlevel playing field.

In the following sections, we will go deeper into these issues and propose solutions for each of them. We want to emphasize that these solutions should not be considered in isolation, but rather integrally as a single solution for the total SEP licensing process. Each individual part of the solution may give rise to obligations that seem to fall more heavily on SEP licensors rather than implementers, or vice versa. However, when considering the integral solution as a whole, we believe that it achieves a fair balance between SEP licensors and implementers.

The solutions presented in this chapter are based on some of the mostly unrelated proposals described in the EC Expert Group report on SEP Licensing and Valuation,Footnote 8 and are presented here for the first time as a holistic solution. In this chapter, we have put a set of proposals together that in combination reduce the main causes of licensing disputes and litigation in a fairly balanced way for SEP licensors and implementers.

III. SEP Transparency

The ETSI database of declared SEPsFootnote 9 was established for the purpose of recording patents that are or may become standard essential and are submitted by members in accordance with their disclosure requirements under the ETSI IP Rights Policy. Due to over-declaration to safeguard compliance with the IP Rights Policy or for strategic reasons, only an estimated 25–40% of the patents in this database are actually essential.Footnote 10 This database is therefore not a reliable source of information for implementers to identify which companies have SEPs, to assess the size of each company’s SEP portfolio, to assess what licenses may be required to produce a standard-compliant product, and to estimate the aggregate royalty for those products. Additionally, it is difficult for SEP licensors to determine a FRAND royalty for their SEP portfolios absent reliable information about the estimated total number of true SEPs for the relevant standard.

The EC 2020 IP Action Plan indicates that the Commission will seek to improve the transparency and predictability of SEP licensing. In particular, the Commission will explore the creation of an independent system of third-party essentiality checks in view of improving legal certainty and reducing litigation costs. Patent pools have shown that large-scale essentiality checks can be done. The EC Pilot Project for Essentiality Assessment of Standard Essential Patents has confirmed the technical and organizational feasibility of such essentiality checks.Footnote 11

An essentiality check system needs to be designed and implemented in an efficient and cost-efficient manner. Patent examiners from patent offices, like the EPO, or attorneys from law firms doing evaluations for patent pools are well positioned to do these checks. Guidelines must be formulated ensuring that essentiality checks are done based on clear and transparent criteria. A supervising body (new or existing) should monitor compliance with these guidelines by the evaluators. This body should also arrange for certification of any entity or person that wants to perform these essentiality checks.

Essentiality findings should be treated as expert opinions, which could be appealed by patent holders and which could also be challenged by implementers and licensees in a fast and cost-effective challenge procedure (for example, within six months is considered feasible) based on a “loser pays” principle. Of course, a party may still bring its case to court, but it is expected that if the independent body does essentiality checks consistently with high quality and courts generally do not come to different conclusions, parties will likely increasingly rely on this body. If a party files an action in court and loses, without having first used the less expensive and shorter essentiality check procedure, the opposing party should be awarded its reasonable legal fees and other costs to be paid by the party bringing suit.

It is often argued that doing essentiality checks for all declared SEPs would take too much time and resources as well as cost too much. This is based on the misunderstanding that checks would be needed for all declared SEPs. However, the essentiality check process should be based on claim charts prepared by the patent holder and submitted to the independent evaluator to start the process. A company will only submit those declared SEPs for evaluation, for which it has sufficient confidence in its claim charts; it will not be willing to pay the evaluation cost (estimated average cost around €5,000 per patent)Footnote 12 for patents with deficient claim charts. This will already eliminate an estimated 50–70% of all declared SEPs.

The cost of essentiality checks can be limited by checking only one member of a patent family in a major jurisdiction (including at least China, European Union, or the United States) and certification by the patent holder that the specified other members of that family include a claim that is substantially similar as the claim found essential in the checked patent. We believe that it is appropriate for SEP licensors rather than implementers to bear these costs, as licensors will benefit the most from having their SEPs checked for essentiality. The reasoning is as follows. In the first phase of SEP licensing negotiations, the licensor and implementer usually discuss the SEP portfolio as presented by the licensor, and the implementer may dispute the essentiality of one or more of the patents. These discussions can take considerable time and may even end up in litigation. By having the licensor’s SEPs checked by an independent, trusted body, any discussions about whether or not presented SEPs are truly SEPs can be avoided. This will save time and effort both for the SEP licensor and the implementer. Since the SEP licensor can avoid this phase of the discussions with all implementers in all different IoT verticals and the implementer can avoid this phase only with the relevant SEP licensor, the total savings for the SEP licensor are higher than for the implementer, so that it seems justified that the SEP licensor should bear the cost for the essentiality checks of its patents. Since essential checks will likely reduce negotiation time and time to agreement, a licensor will also likely receive revenues earlier. Also, the practical complications of allocating these costs among an unknown number of implementers of unknown sizes recommend allocating these costs to the SEP licensors. Moreover, the SEP licensor is likely to earn a “return” on its investment in essentiality checks through the cost savings from more efficient licensing negotiations.

Another important aspect often not addressed is the timing of essentiality checks. Delaying these checks until years after the market for certain standard-compliant products has developed will result in little improvement in the licensing ecosystem. By that time SEP licensors and implementers will already have negotiated and concluded licenses, disputes will already have arisen, and litigation initiated, settled, or adjudicated. Checks need to be done as soon as possible in the early stages of development of the market for a category of standard-compliant products, which will allow the checks to take place before licensors and implementers start their negotiations.

For each new product category, the relevant SEPs need to be identified. As the various products for different IoT verticals will be launched at different points in time after the adoption of the standard, licensors’ investments in essential checks will also be spread out over time. Moreover, it should be realized that the 5G standard comprises a baseline component (New Radio/Network Core-NR/NC) and additional components for the different use cases related to different IoT verticals, which will similarly spread out essentiality checks over time.

Checks must be done for granted patents only. Currently, on average, more than 50% of all declared SEP families have a granted patent in one of the major market countries at the time of publication of a standard, but with significant time lag in granted patents across companies due to different filing routes.Footnote 13 The percentage of granted patents will grow over time. For standard-compliant product categories that enter the market several years after the adoption of the standard, the percentage of granted patents will have increased significantly, and it will be large enough to give a reliable picture of the size of licensors’ SEP portfolios and thus also their share in the total stack of SEPs for those product categories. Since the first product category enters the market relatively shortly after the publication of a standard (for cellular standards, these are usually smartphones), the percentage of granted patents is still relatively low, and the distribution of granted patents across companies is skewed. This may make the picture of the SEP landscape less reliable. Many SEP holders already make use of accelerated patent examination procedures, and this should be further encouraged to allow the percentage of granted patents to increase more rapidly after publication of a standard.

Additional measures could be taken to further stimulate companies to take steps to have their patents granted quickly (or at least, not to delay the process) as well as to have their patents evaluated quickly after grant. For example, these practices can be encouraged by adopting rules that companies may only assert SEPs that have been confirmed to be essential after a check by a certified body. Alternatively, rules could be adopted that companies can only collect royalties after the date they have submitted their alleged SEPs for an essentiality check.

Essentiality checks by an independent body, based on agreed guidelines and supervised by an authority to ensure that they are done consistently and with high quality, is a first and important step in promoting a smoother licensing environment for SEPs. On the one hand, essentiality checks will assist SEP holders in estimating their SEP share in the total stack of SEPs for a category of standard-compliant products and use that information as an input to determine the royalty for their SEP portfolio, taking into account a reasonable aggregate royalty for the total stack. On the other hand, essentiality checks will assist implementers in identifying the companies from which they may need to take licenses for their products, to estimate the aggregate royalty for their products, and to take those considerations into account in their business plans. In the aggregate, these steps will result in more efficient licensing negotiations and fewer disputes and litigation concerning essentiality.

IV. Improving on Validity

A. Validity Rates

Licensing negotiations tend to follow a rather fixed pattern. In the first phase, the implementer presents its arguments why one or more of the asserted SEPs are believed to be non-essential. In the second phase, the implementer makes arguments why one or more SEPs are believed to be invalid. As discussions about validity involve judgments about whether or not a patented invention is obvious, it might not be easy to reach agreement on validity. The objective of implementers is to try to undermine the SEP position of the licensor by advancing claims that the royalty offered by the licensor is too high and not FRAND. In cases where the parties are not able to reach an agreement and proceed to litigation, the implementer will in many cases contest the validity of the SEPs being asserted against it.

Since the introduction in the United States in 2012 of inter partes review (IPR),Footnote 14 implementers faced with SEP patent assertions have used IPRs in an effort to invalidate the SEPs. Today many large implementers file IPR petitions as a response to a SEP assertion letter while, at the same time, ensuring that they take those steps in line with the Huawei–ZTE negotiation framework and, as a result, are likely to be viewed as a willing licensee who is negotiating in good faith. In some cases, large implementers file multiple IPR petitions, which may place financial and resource pressure on the SEP licensor. This strategy may discourage smaller SEP licensors from asserting their SEP portfolios, which may have a negative impact on their investments in innovation and willingness to participate in standard-setting processes in the future.

Based on various reports, the PTAB invalidates about 65% of the challenged patent claims in accepted cases (in the term used by the PTAB, “instituted petitions”).Footnote 15 Also, courts in Germany have declared 33% of all litigated patents in the period 2018–2020 fully invalid and 41% partially invalid.Footnote 16 These rates are more or less in line with the results of opposition proceedings against European patents before the European Patent Office.Footnote 17 These figures apply to all patents and not only SEPs, but it can be assumed that invalidation rates for SEPs will not be lower than for non-SEPs. Any SEP invalidity determinations reached through these adjudicative processes will impact a licensor’s SEP position toward not only the implementer involved in each proceeding but also all other implementers. These invalidation rates show that implementers have a substantial likelihood of success in contesting the validity of SEP patent claims in litigation, IPRs, or oppositions. An implementer can use the risk of invalidation to try to secure better SEP royalty terms through settlement prior to adjudication. On the other hand, SEP licensors might already price into their royalty rates the likelihood that roughly half of their SEPs may be declared invalid in litigation, IPR, or oppositions.

It is not expected that this situation will change any time soon. As long as major patent offices continue to examine all patent applications with approximately the same degree of scrutiny, the percentage of invalidated claims of granted patents that are used in SEP licensing is not likely to change. Implementers will continue to contest the validity of asserted SEP patents, and SEP licensors will continue to be faced with invalidations of patents in their SEP portfolios offered for a license. Nonetheless, it still makes sense to consider mechanisms that may provide a reasonable estimate of whether the patent will be upheld or invalidated, quickly and easily, right at the beginning of negotiations.

B. In-Depth Prior Art Searches

SEP licensors could undertake in-depth prior art searches on their SEPs prior to submitting them for an essentiality check or even prior to starting to prepare claim charts. The quality of state-of-the-art semantic search engines, often with additional artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) functionalities, has improved in recent years, especially for application in the field of information and communication technologies. These engines could be used to conduct fast, low-cost full-text searches against patent databases without limitations on technical classes in the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system or other classification systems. Companies offering these search engines as a commercial service are readily available. The searches may reveal relevant prior art that has not yet been considered in patent examination procedures. Based on this prior art, a patent holder could decide that the patent in its current form is not likely to stand a validity test in court (or in an IPR) and consequently that it hardly makes sense to spend money on having it checked for essentiality. Patent holders may also opt to use these search engines during the examination procedure and bring any relevant prior art to the attention of patent examiners so they can take this prior art into account when evaluating the patentability of the claimed inventions. If used pre-grant, these prior art searches would contribute to reducing the likelihood that SEPs will be declared invalid when scrutinized in court or in IPRs. The post-grant use of such searches would make it possible to predict the answer to this question with reasonable certainty. Both the pre-grant and the post-grant use may reduce litigation based on invalidity claims of litigated SEPs. However, if such prior art searches show no indication of invalidity, an implementer would still have the right to claim the invalidity of SEPs in court. Litigation costs considerable time and money for both parties, and, moreover, it may take years before a final decision is made about the validity of a SEP, and clarity is achieved not only for the parties involved in litigation but also for other potential licensees.

C. Validity Challenges

It is desirable to achieve the clarity described in the preceding section in an early phase of the development of a standard-compliant product market. This could be achieved if implementers could challenge the validity of asserted SEPs in an out-of-court challenge procedure before panels of independent patent experts. These panels could be selected from a pool of experienced and qualified patent experts certified by an independent body that facilitates and supervises these panels. This body could, for example, be the same body supervising the essentiality checks as described in Section III.

The challenge procedure should be relatively fast and inexpensive. It seems feasible that with a strict process where parties bring their arguments and counterarguments in a limited number of rebuttals, panels should be able to produce valid opinions in about six to seven months. This should also keep the cost relatively low and well below the average cost of IPRs, which are estimated between $300,000 and $600,000.Footnote 18

These panels would issue opinions about the likelihood that a patent will withstand a validity challenge when scrutinized in court (or in an IPR). They could not invalidate a patent, as this can only be done by a court. The parties could agree to accept the opinion of such a panel, or a party not accepting the opinion of a panel could elect to go to court. If an implementer went directly to court to claim invalidity without first using the faster and less expensive validity challenge panel and the patent’s validity is upheld in court, the implementer should be ordered to pay the licensor’s reasonable out-of-pocket costs. The same should apply to a SEP licensor who commences litigation without having completed the challenge procedure, provided the implementer initiated the challenge to the SEP’s validity in a timely manner. This would create an incentive for both licensors and implementers to use the validity challenge procedure before going to court. This would also counter any hold-up or hold-out strategies.

If the panels produce high-quality opinions and courts generally do not come to different conclusions, the parties will increasingly rely on such opinions and will tend not to bring such cases to court. This would reduce the number of litigations based on claims that asserted SEP patents are invalid.

V. Incentivizing Implementers to Seek Licenses

A. Publishing Standard License Terms

Even when the SEP owners and the size of their SEP portfolios are known in the case of a particular standard, it is unlikely that implementers will approach the relevant licensors for their standard-compliant products. A SEP licensor will still have to identify the implementers that commercialize standard-compliant products using their SEPs and assert their SEPs against these implementers. This wait-and-see approach may mean that an implementer is approached by SEP licensors years after they started to commercialize standard-compliant products. Without information about the estimated aggregate royalty for these products, many (or even most) implementers would not take an estimated aggregate royalty into account in their business plans and would not make provisions for the royalties they will have to pay. In the meantime, these implementers may have considerable liability exposure to royalties owing on sales made prior to being approached by a SEP licensor. This liability exposure will increase even further, as licensing negotiations may also take considerable time (easily 18–36 months). Although SEP licensors are usually willing to give discounts on royalties for past-use sales, the outstanding past sales amount may create such a financial burden for the implementer that this may prolong negotiations even further.