Geoffrey Turner, one of the foremost authorities on the architecture of the Neo-Assyrian empire, passed away in Brussels on 7 October 2018 after a long illness. Born on 1 December 1941 in Leicestershire, England, Geoffrey received a BA in 1964 in Hebrew and Assyrian at London University's School of Oriental and African Studies and University College, with additional studies in the Ancient History of Egypt and the Near East and Mesopotamian archaeology. Already in his undergraduate days, Geoffrey collected unusual objects for a college student, such as Roman coins, old pistols, and antique books, and he remained a collector his entire life.

Geoffrey continued at London University pursuing graduate studies at the Institute of Archaeology, earning an MPhil in Archaeology in 1967 based on the thesis “Late Assyrian Palaces and their Mesopotamian Antecedents with special reference to the inscriptions”, written under the supervision of Seton Lloyd, with assistance on linguistic issues from D. J. Wiseman. While researching his MPhil thesis and articles based thereon, Geoffrey spent 15 months between 1964 and 1968 working in Baghdad and northern Iraq with the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, participating in the 1965 and 1966 excavations at Tell el Rimah directed by David Oates, and working in the Iraq Museum in association with members of the Iraq Department of Antiquities. During this period, he also traveled widely in neighbouring countries.

Immediately after completing his thesis, Geoffrey published three important articles in Iraq: The first, “The Palace and Bâtiment aux ivoires at Arslan Tash: A Reappraisal” (Iraq 30, 1968), provided new analyses of the formal characteristics and dating of those buildings in light of more recent excavations at Khorsabad and Nimrud. The second, “Tell Nebi Yūnus: The Ekal Māšarti of Nineveh” (Iraq 32:1, 1970), was the first in-depth study of this major Assyrian palace based on a close analysis of the textual building accounts that describe the structure, which at that time was otherwise known only from a few poorly-documented soundings. The third, “The State Apartments of Late Assyrian Palaces” (Iraq 32:2, 1970), gave a detailed typology of the various room patterns utilized in Assyrian palatial structures, and due to its extraordinary clarity and practical utility it has become one of the most cited articles in Assyrian architectural studies.

In 1969, Geoffrey joined Christie Manson & Woods, where he stayed on as a consultant for many years. In 1972 he established Galerij Ancient Art BV in Amsterdam, dealing in Egyptian, Middle Eastern and Classical antiquities, succeeded in 1990 by Geoffrey Turner Ancient Art in Brussels, with a primary focus on pre-Islamic antiquities. Despite the demands of his business career, Geoffrey continued to make time for his scholarship, notably with “South Arabian Gold Jewellery” (Iraq 35, 1973), a preliminary catalogue and analysis of a group of this material that was on loan to the British Museum from the Aden Museum.

Geoffrey's next projects were collaborations with Richard Barnett, then Keeper of the Department of Western Asiatic Antiquities of the British Museum, on two monumental publications of Assyrian sculptures for the British Museum Press: “Notes on the Architectural Remains of the North Palace” in Sculptures from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (1976), and “The Architecture of the Palace” in Sculptures from the Southwest Palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh (co-authored with Barnett and Erika Bleibtreu, 1998). In 1986 as Geoffrey was completing his manuscript for the latter publication, Erika Bleibtreu showed him a copy of my recently completed dissertation on Sennacherib's palace, and he wrote asking me if we could meet the next time he was in Philadelphia to discuss the various problems posed by the palace.

We met soon thereafter, initiating a very fruitful Southwest Palace dialogue, not to mention a close friendship, that continued until Geoffrey's death. Initially I was able to provide Geoffrey with some observations on the throne-room suite based on my 1989 field season at Nineveh, which he incorporated into his chapter of the British Museum publication. After that book appeared in 1998, Geoffrey found that two sheets of Layard's sketch plans had inadvertently been omitted, so he wrote to me that he was “doing a short article as an addendum to the book, publishing these omissions”. I wonder if he had any inkling at the time that his work on this “short article” would ultimately fill the next twenty years and expand into a manuscript of 600,000 words on nearly 2000 typed pages!

While the British Museum book was in press, I had located and published (in Iraq 57, 1995) a previously unnoticed set of notes by Layard describing the rooms excavated during his second campaign at Nineveh of 1849–1851, which Geoffrey said inspired him to begin a systematic search through all the Layard Papers in the British Library. The initial results of this research soon appeared in two long articles in Iraq: “Sennacherib's Palace at Nineveh: The Drawings of H. A. Churchill and the Discoveries of H. J. Ross” (Iraq 63, 2001), which documented excavations on the palace during the interval between Layard's two campaigns, and “Sennacherib's Palace at Nineveh: The Primary Sources for Layard's Second Campaign” (Iraq 65, 2003), providing detailed descriptions of source documents in the British Library and the Department of the Middle East, including the previously omitted sketch plans, as well as details on the artists who had worked at Nineveh and a list of attributions for their drawings.

Geoffrey had envisioned the 2003 article on the primary sources as the introduction to a longer article or series of articles intended for Iraq on Layard's second campaign, writing in 2002 “This ‘work’ is a continuous source of enjoyment and satisfaction, but it will probably be a very long article, probably in two installments”, and two years later, “New ideas and bits and pieces keep turning up: and as I start on each new section, room or whatever, I never know what I shall come across”. By this time it was clear that Geoffrey's article was becoming a book, which over subsequent years expanded to include chapters on Layard's first excavations at Nineveh in 1847, as well as excavations at Nineveh after Layard's departure, carried out under the direction of Rawlinson, Rassam, and others until Rawlinson left Baghdad in 1855. For the latter chapter, in 2008 Geoffrey gained access to the rich and previously largely neglected primary source material on the Nineveh excavations in the British Museum's Central Archives. Of this he later wrote “I spent hours in the airless vaults of the Museum going through the many volumes of the Original Papers, and then the Officers' Reports, the Letter Books where necessary, as likewise the Minutes of the Committee Meetings of the Museum's Trustees, etc., et alia. None of these volumes are indexed as such”.

The final product of this research, completed shortly before Geoffrey's death and tentatively titled The British Museum's Excavations at Nineveh, 1846–1855, essentially constitutes the much-delayed final report on these important excavations, while also, as Geoffrey noted, “throwing light on the more mundane and everyday occurrences and incidents, both archaeological and personal.” Geoffrey's study makes accessible a tremendous volume of previously inaccessible primary source material, and provides a comprehensive analysis of the results of the excavations.

Those who have tried to read the often execrable penmanship in these original documents will fully appreciate what Geoffrey has accomplished in rendering into legible form the great volume of plans, notebooks, diaries, and letters of Layard, Rawlinson, Canning, and others. As Geoffrey wrote in 2002, “Although those who have never looked at Layard's notebooks, i.e. 99%, will never believe that it is often impossible to be certain of his text, one can only stress this over and over again when referring to the field notes in any publication”, and a few months later, “it takes a lot of doing – it is impossible to read much of the Court I/VI [entry] correctly without looking at it time after time. Some days I can read it, others not.” Likewise, those who have endeavoured to make sense of the sketchy and frequently contradictory information in the 19th century plans, drawings, notes, and publications will greatly appreciate the rigour with which Geoffrey examined these sources and offered convincing solutions to many of the problems they pose. It is hoped that this enduring monument to Geoffrey's scholarship will be published in due course.

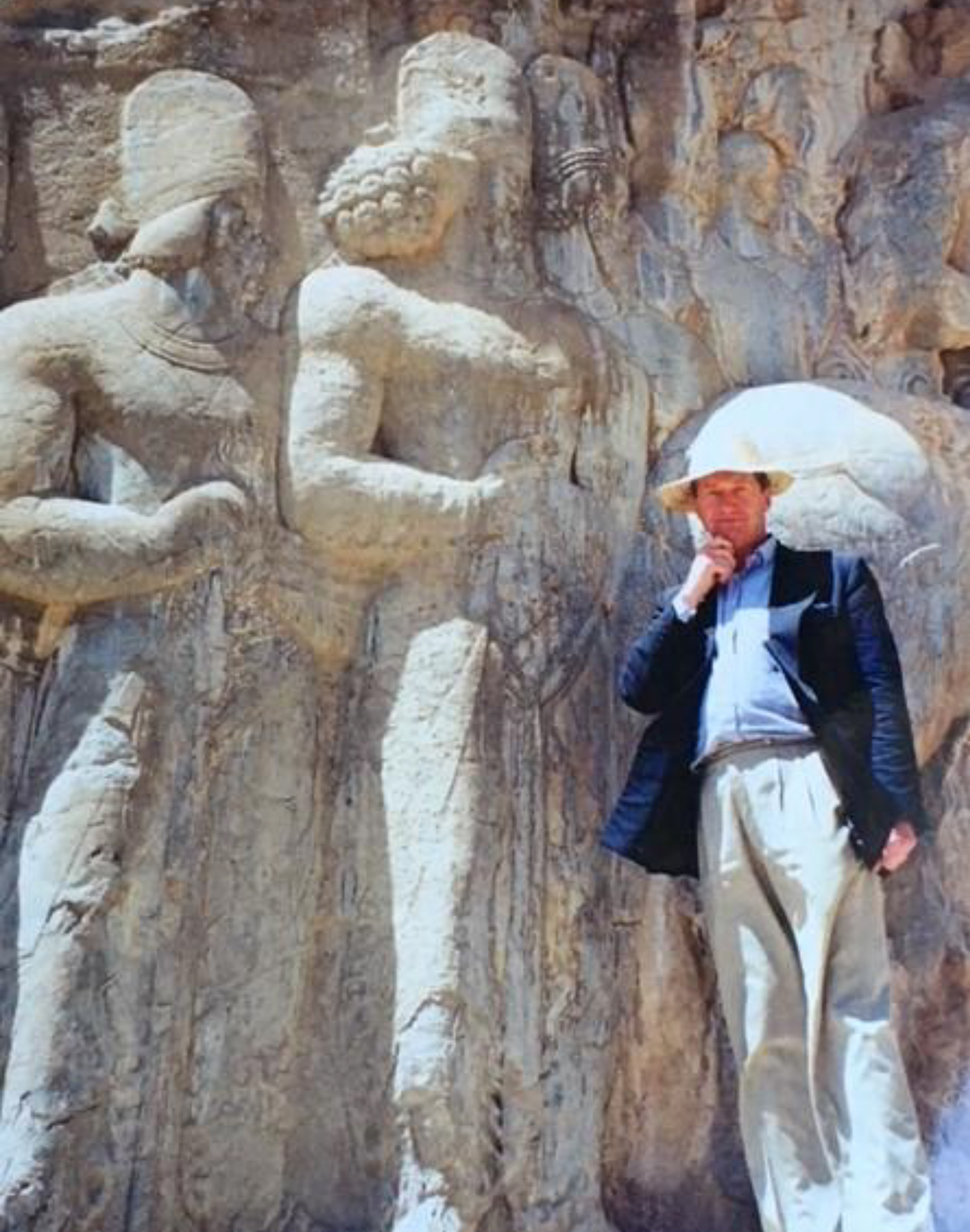

Those who knew Geoffrey personally will long remember his wit and smile, gentle voice (except when speaking to his typewriter), proper dress (always in a suit), courtesy, friendliness, and great generosity. He enjoyed good food, including shopping and cooking. According to his wife Petra, “It was he who did all the shopping at the local markets. He found great pleasure in speaking Arabic with the stall-keepers and when Geoffrey arrived at the market the stall-keepers all started holding up their strawberries, of which Geoffrey was very fond.” He was a familiar sight in his neighborhood walking a pair of lively beagles for several hours every afternoon, during which diversions new ideas would come to him. Geoffrey was clearly born at least a century too late. He was extremely (dare I say willfully?) old-fashioned, with no interest in motorcars or other modern contrivances. He recently wrote to me, “I of course do not have such immoral gadgets as a washing-up machine – I remember my father bought one for the school holidays when they were first invented, but it kept breaking down.” Petra reports “He spoke about the wireless and never used the word radio in his entire life.”

As far as I know, he never touched a computer. One of his few concessions to modernity was his typewriter, a device he hated and only used to prepare the final versions of his handwritten manuscripts – a process he characterized as “four to six weeks of a continuous bad temper” – and occasionally for correspondence when recipients complained too much about his handwriting. Near the end he wrote, “A pot of ink and an old-fashioned quill are far better.” And those handwritten letters, occasionally embellished with random smears or blotches of ink, constitute the great majority of his correspondence with me, despite his quip that “obviously my handwriting is getting as bad as Layard's”. His conscience was clear, however, in the knowledge that “since I derive so much fun trying to read the letters of Henry Rawlinson, Sir Stratford Canning (which can be very difficult if not impossible) and Layard's notebooks, I presume I give pleasure to others who try to disentangle my cryptic epistles”. In retrospect, he was right.

Geoffrey is survived by his wife Petra Boekstal, his sister Joanna Boughton-Leigh, his two adorable beagles Daisy and Milly, and a body of scholarly work that has tremendously enriched ancient Near Eastern studies.