Introduction

The journey to qualifying as a cognitive behavioural therapist typically involves the completion of a university based, Masters level training course that combines didactic teaching with clinical skills practice, supervision, directed reading and a placement within a mental health setting (Bennett-Levy and Beedie, Reference Bennett-Levy and Beedie2007; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009; Liness et al., Reference Liness, Beale, Lea, Byrne, Hirsch and Clark2019a; Turpin and Wheeler, Reference Turpin and Wheeler2011). In the UK, the English Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme offers one such example of this where teaching content and supervision are supported by a national curriculum (Liness and Muston, Reference Liness and Muston2011; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2019; Turpin and Wheeler, Reference Turpin and Wheeler2011) and trainees are usually employed by NHS trusts attending a year-long ‘high intensity’ course. Trainee skills are regularly measured against established standards and measures including the Roth and Pilling Competence Framework (2007) and the Cognitive Therapy Scale-Revised (CTS-R) (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Reichelt, Garland, Baker and Claydon2001).

The majority of trainees have usually worked in other allied health professions or therapeutic roles prior to embarking on this journey (e.g. psychological wellbeing practitioner (PWP), mental health nursing or person centred counselling), yet may have minimal or no CBT skills (Liness et al., Reference Liness, Beale, Lea, Byrne, Hirsch and Clark2019a; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2018). Most already possess the ‘basic competences’ (e.g. ‘knowledge and understanding of mental health problems’) and throughout the training year gradually develop or refine ‘basic CBT competences’ (e.g. ‘ability to structure a session’), specific competences (e.g. ‘ability to elicit key cognitions’), problem-specific competences (e.g. Clark’s panic disorder model) and finally ‘meta-competences’ (e.g. the capacity to manage obstacles to CBT therapy) (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007).

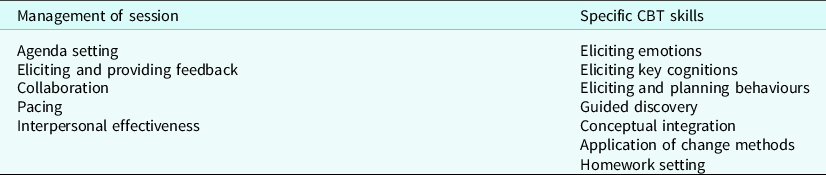

The challenges of role transition have previously been highlighted (e.g. Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020) as Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012) aptly state that ‘the HIT trainee is expected to swiftly learn a new set of conceptual skills alongside a new psychotherapeutic vocabulary’ (p. 352). One example of this is the CTS-R which measures trainee abilities in general therapeutic and session management skills and specific CBT skills (Liness et al., Reference Liness, Beale, Lea, Byrne, Hirsch and Clark2019b) (see Table 1). It is commonly used in CBT training courses, especially those that follow the IAPT curriculum. Utilising the Dreyfus scale, it consists of 12 criteria that are awarded a score between 0 and 6 (incompetent through to expert), with an overall score of 36 out of 72 needed to pass.

Table 1. CTS-R criteria (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Reichelt, Garland, Baker and Claydon2001)

Some of these skills may be more difficult to master than others and at present little is known about the order in which or speed that each one develops (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014; Kennedy-Merrick et al., Reference Kennedy-Merrick, Haarhoff, Stenhouse, Merrick and Kazantzis2008; Maruniakova and Rihacek, Reference Maruniakova and Rihacek2018; Waltman et al., Reference Waltman, Hall, McFarr, Beck and Creed2017). For example, is agenda setting easier to master than eliciting key cognitions? Item 9 on the CTSR is guided discovery (GD), which represents part of the new vocabulary and is one of the many conceptual skills and terms that trainees must become au fait with. Commonly referred to as the ‘Socratic method’ (Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017), GD is a specific way of eliciting information from clients and helping them to develop meta-cognitive awareness and is considered central to the practice of cognitive therapy (Beck, Reference Beck1995; Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Fairburn, Padesky, Reinecke and Teesson2014; Neenan, Reference Neenan2009; Padesky, Reference Padesky1993). The use of GD arguably affects all aspects of assessment and treatment; for example, when undertaking psychoeducation, a therapist could adopt a didactic approach by simply telling a client that they will not faint during a panic attack because their blood pressure is unlikely to drop when they are anxious (Wells, Reference Wells1997). Conversely, the therapist could elicit from the client their understanding of what they think needs to happen in their body for them to faint. Both discussions will affect the pacing of the session, the engagement of the client’s cognitions, emotions and behaviours and the level of collaboration between therapist and client (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Reichelt, Garland, Baker and Claydon2001; Wells,Reference Wells1997).

Defining guided discovery

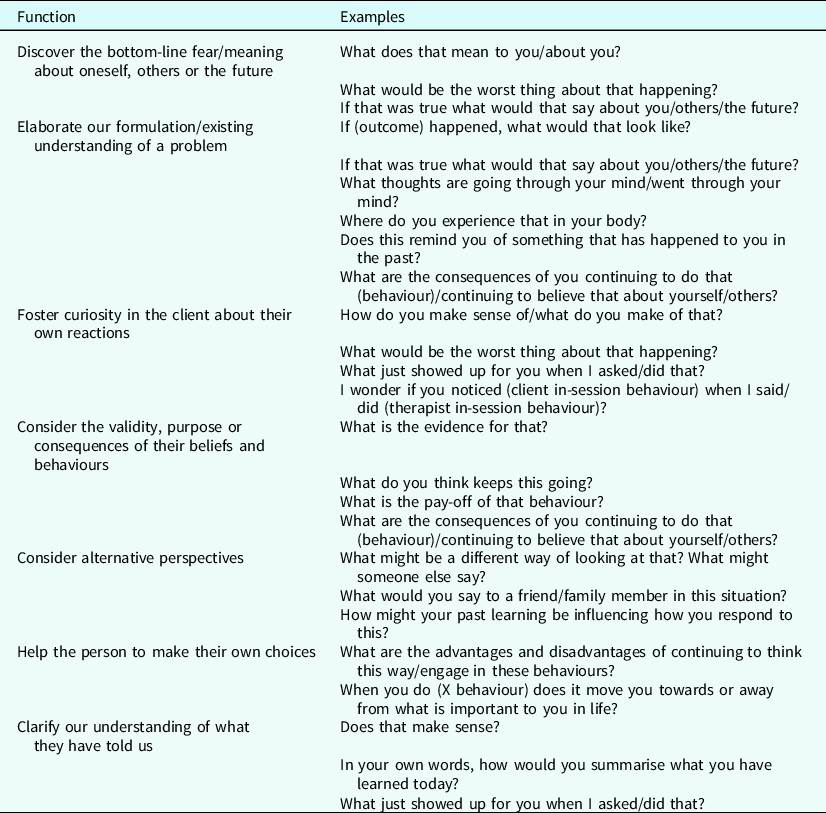

CBT practitioners deploy a range of skills during assessment and treatment sessions with clients. Some of the dialogue will involve closed questions which only require yes or no answers (e.g. ‘are you taking anti-depressant medication?’) whilst other conversations will involve more open questions (see Table 2). Both the CTS-R and Roth and Pilling competences require trainees to develop specific skills in GD and ‘Socratic questioning’ (SD). These terms are often used interchangeably in the literature and clear delineation of the two is difficult to find. The lead author suggests that one way to differentiate the two is to consider Socratic questioning as the tool that is used during a process of guiding the client’s discovery of new or hidden information. For example, the therapist uses Socratic questions (‘Did your prediction come true or did you find something else out from doing the experiment?’) to assist the client in determining whether or not previous assumptions about the world hold true or if a different explanation emerges. The type of questions asked, their sequence and the pace reflect a shift in session from other therapeutic skills such as information gathering.

Table 2. The style and stance of guided discovery

According to Roth and Pilling (Reference Roth and Pilling2007), GD consists of four steps – asking questions to uncover relevant information outside the client’s current awareness, accurate listening and reflection by the therapist, summarising the information discovered and forming a synthesising question that asks the client to apply the new information discussed to the client’s original belief. GD can also be seen as consisting of a style that is open and inquisitive and a set of techniques (e.g. downward arrowing) that are underpinned by the use of Socratic questions (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Reichelt, Garland, Baker and Claydon2001; Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007). GD therefore represents both a style of working (e.g. a way of phrasing questions or responding to challenges in therapy) often likened to that of the TV detective Columbo (Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017; Scott, Reference Scott2009) (see Table 2) and a stance towards the client and the process of change within therapy (e.g. the client has or can find their own answers to their problems).

The style and the stance

A guided discovery stance towards therapeutic change involves creating the conditions for a client to reach their own conclusions or discoveries through the facilitation of genuine curiosity about themselves or the world (Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017). Crucially, this should be done without resorting to debate or persuasion from the therapist (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Reichelt, Garland, Baker and Claydon2001; Padesky, Reference Padesky1993; Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007). Socratic questioning is a style of interacting with the client that involves asking a range of open questions designed to elicit pertinent information that is currently outside the client’s awareness (James et al., Reference James, Morse and Howarth2010; Neenan, Reference Neenan2009). Table 3 gives some examples of Socratic questions and their related functions and is provided to trainees on the CBT training course where the first author is a tutor. By coming to their own conclusions, it is proposed that this leads to a deeper level of learning for the client in contrast to the therapist simply telling them what to do or how or why to think differently (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennell, Hackman, Mueller and Westbrook2004; Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Fairburn, Padesky, Reinecke and Teesson2014; Kolb, Reference Kolb1984; Padesky, Reference Padesky1993). As James et al. (Reference James, Morse and Howarth2010) put it, ‘Socratic questions are more likely to encourage the analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of different sources of information. This suggests that Socratic questioning utilizes “higher” thought processes and may ultimately have greater impact on change’ (p. 89). Trainees are typically taught how to use guided discovery through a variety of methods such as didactic lectures, reading book chapters or papers on the topic, tutor modelling, expert video demonstrations and role-play (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009; James et al., Reference James, Morse and Howarth2010; Padesky, Reference Padesky1993).

Table 3. Frequently used Socratic questions and their intended functions

Ways of measuring therapist skill in GD

Previous research has found that GD is one of, if not the most difficult skill to master during CBT training (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014; Waltman et al., Reference Waltman, Hall, McFarr, Beck and Creed2017), yet until recently there has been a sparsity of tools available to measure competence or assist trainee understanding in this key area of practice. As stated earlier, the CTS-R, an updated UK version of the original CTS (Young and Beck, Reference Young and Beck1980) is a tool that is commonly used in UK CBT training (Clark, Reference Clark2011), particularly within summative assessment and supervision where supervisor and supervisee might watch or listen to a recording of a therapy session to gauge the level of skill that has been demonstrated. For the GD item, scoring ranges from 0 (complete absence of the skill) through to 6 (expert), with the former characterised by no evidence of GD within the session and a high degree of ‘hectoring and lecturing’ (Blackburn et al., 2000; p. 11) whilst the latter would include strong evidence of an open and inquisitive stance from the therapist leading to deeper understanding of problems or solutions within the client.

More recently, Padesky (Reference Padsesky2020) has developed a Socratic Dialogue Rating Scale and Coding Manual which aims to provide ‘formative guidelines for therapists, supervisors, and consultants in order to improve use of Socratic dialogue in psychotherapy’ (p. 1). Consisting of four aspects of competence (informational questions, empathic listening, summaries and synthesising questions), this provides considerably more detail than the CTS-R for trainees and raters to know what to look for. It would appear that the scale can be used by qualified, experienced practitioners as well as trainees as part of their ongoing clinical supervision or as a self-supervision exercise. The degree to which this manual has been accessed by UK CBT training courses is yet unknown.

Guided discovery in action – from classroom to clinic room

Learning to use GD and its underpinning Socratic dialogue firstly involves grasping the technical or ‘declarative knowledge’ (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006) of what it means and how it differs from everyday conversations (Carey and Mullan, Reference Carey and Mullan2004). It also involves an understanding of its purpose and utility within assessment and treatment (Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Fairburn, Padesky, Reinecke and Teesson2014; Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017). Reading the Padesky manual is one way of beginning to acquire a technical understanding of what needs to be demonstrated in clinical practice. Once the trainee has a declarative understanding of GD, they learn how to use it practically through tutor modelling and during role plays with fellow trainees before starting to incorporate it into the assessment and socialisation phase of CBT. In other words, they convert declarative knowledge into ‘procedural knowledge’ (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006). Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009) describe the procedural system as ‘a storehouse of skills, attitudes and behaviours in action’ (p. 573). One example of emerging procedural knowledge would be to help a client understand the deeper meanings of their negative automatic thoughts (i.e. ‘I will make a fool of myself at the party’). Downward arrowing is one such example of a Socratic questioning method where a series of ‘what would that mean?’ or ‘what would be so bad about that?’ questions are asked to discover the ‘bottom line’ or core belief (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Fennell and Hackmann2010; Wells, Reference Wells1997). Revealing this bottom line may enhance the existing formulation or help the therapist and client to decide their next steps such as devising a behavioural experiment to test out if certain predictions come true (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennell, Hackman, Mueller and Westbrook2004). There are caveats to how and when this is done in therapy (see James, Reference James2001; James and Barton, Reference James and Barton2004) yet due to ‘when–then rules’ being acquired through clinical experience (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006), it is impossible to teach trainees all of the different scenarios around when to be Socratic and when not to. As a therapist becomes more experienced, they draw upon their declarative and procedural knowledge but also engage their ‘reflective system’ to draw upon clinical experiences where guided discovery has been beneficial and when it has led to dead ends or impasses (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017). Experienced therapists thereby utilise ‘meta-competences’ where they have learned the nuances of when to adopt a Socratic approach and when not to (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; James and Barton, Reference James and Barton2004; Neenan, Reference Neenan2009; Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007).

Barriers to using guided discovery

Simply possessing an understanding of what guided discovery is and how to use it might not fully explain difficulties in its practical application (see Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Townend and Sloan2008) for a detailed exploration of the many potential barriers). A theoretical understanding of GD may become lost in translation between reading a book chapter or attending a lecture and being sat with a distressed client mid therapy session. Learning a new skill often leads to feeling de-skilled (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012) and in times of uncertainty about whether a new skill will work as intended, trainees may resort to what they know and trust. For example, according to Waltman et al. (Reference Waltman, Hall, McFarr, Beck and Creed2017), ‘Very often CMH clinicians fall into the trap of advice giving and telling clients how to think’ (p. 7). The short term pay-offs from engaging in this behaviour might include a sense of being useful and removal of clinician anxiety. Consequently, this could be a very difficult habit to break if it has formed a significant part of a trainee’s previous job role and is negatively reinforced (Kjøge et al., Reference Kjøge, Turtumøygard, Berge and Ogden2015; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020).

Aims of current study

There is a need to understand why certain aspects of CBT trainee skill development are more challenging than others (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014; Waltman et al., Reference Waltman, Hall, McFarr, Beck and Creed2017). To the authors’ knowledge, there has been no research published on specific aspects of CBT training (e.g. learning to use guided discovery) that interferes with role transition. There is limited existing research on the overall role transition from other mental health professional roles such as PWP, counsellor or nurse to CBT therapist (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020). Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012) conducted semi-structured interviews with six mental health nurses about their transition to trainee high intensity therapists and Wilcockson (Reference Wilcockson2018, Reference Wilcockson2020) used a grounded theory methodology to analyse the challenges of role transition for person centred counsellors, mental health nurses and a KSA (non-core professional group).

As a tutor on a CBT training programme, the first author has observed across several cohorts that GD is a skill that many trainees consistently struggle to acquire by the end of the course. It is of particular interest to understand how they assimilate this new skill and the challenges this might generate (e.g. if it involves doing the direct opposite of what they might have done in their previous role). As noted by Bennett-Levy and Beedie (Reference Bennett-Levy and Beedie2007), ‘the trainee’s voice has been relatively absent in the training literature’ (p. 62) and little is known at present about the experiences of CBT trainees when learning specifically about the theory and practical applications of GD.

The purpose of the current study, therefore, was to gain a better understanding of trainee experiences of learning and then applying GD in their clinical practice in order to develop a preliminary model that might assist in explaining this process to trainees, supervisors and trainers. Having a shared language for discussing facilitative or inhibiting factors for learning GD might assist in generating more targeted methods of teaching, supervision and self-reflection.

Method

A convenience sample was used consisting of a cohort of trainees who were in the final module of their IAPT high intensity course, studying at the institution where the researchers are based. The course follows the IAPT curriculum (see Liness and Muston, Reference Liness and Muston2011) and trainees are introduced to a variety of teaching and learning methods within the ‘Fundamentals of CBT’ module at the start of the course to assist with their declarative and procedural knowledge of GD; for example, videos of Padesky explaining what GD is, tutor modelling, role play and vignettes from classic introductory texts (e.g. Beck, Reference Beck1995: Padesky, Reference Padesky1993; Wells, Reference Wells1997).

GD skills are then refined within university group supervision and one-to-one workplace supervision. The Socratic method is further revisited in lectures as a way of developing disorder specific models, designing and testing behavioural experiments, managing client resistance and roadblocks, and reviewing learning in the ‘CBT for Anxiety Disorders’ and ‘CBT for Depression’ modules (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennell, Hackman, Mueller and Westbrook2004; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001; Wells, Reference Wells1997)

Design

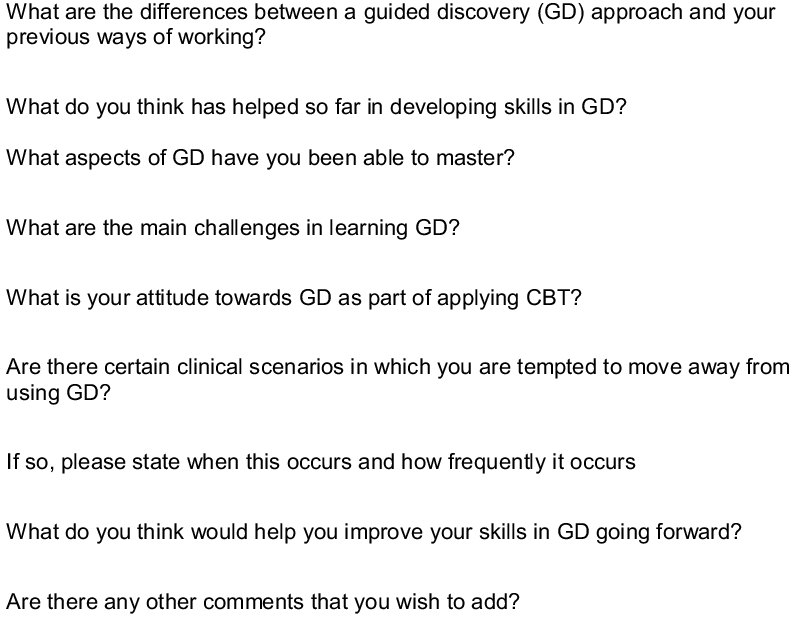

A questionnaire was developed (see Fig. 1) using online surveys, and involved participants answering eight open-ended questions that sought to understand their experience of learning skills in GD. In particular, the questions looked to determine factors that assisted in understanding and practising GD and potential obstacles.

Figure 1. Survey questions.

Participants

Due to there only being one male enrolled on the course, gender was not requested in the questionnaire in order to protect anonymity. In terms of background roles prior to commencing training in CBT, 83.3% (n = 15) had been PWPs, 11.1% mental health nurses (n = 2), 11.1% assistant psychologists (AP; n = 2) and 5.6% (n = 1) were ‘other’ unspecified. Two of the participants had identified two previous roles (PWP and AP). Trainees were provided with a link to access information about the study and an online survey to which it was explained that participation was optional. Of the 22 trainees who were invited to take part, 18 (81%) participated in the research.

Data analysis

As it was the intention to develop a tentative model from the data, a grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967; Strauss and Corbin, 1998) was adopted in that the authors started with no a priori assumptions about factors that increase or decrease trainee skill in GD. As a tutor on a CBT training course, the first author acknowledged that their own assumptions about the importance of guided discovery as a core skill had led to this research project. On this basis, the literature review was not undertaken until after the open coding phase. Furthermore, questions had been designed to generate open rather than closed responses and to explore a balance between what participants perceived to be helpful and unhelpful in learning GD. Finally, a reflective diary was used to track opinions about the likely responses in the data and emotional reactions to participant responses.

Beginning with line-by-line (open) coding of all 18 trainee responses to each question, a series of inductive, provisional categories or ‘gerunds’ (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Gott and Hoare2017) and sub-categories were generated through the identification of the most frequently occurring (e.g. important) or related words (e.g. ‘rules’, ‘resistance’). The next phase involved a constant comparison of the provisional sub-themes, assisted by memo writing, and this led to some changes through the axial coding process (see Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). As a means of reducing the potential of researcher bias due to the first author being a practising CBT therapist and trainer, the second author (a psychologist and non-CBT practitioner) independently audited the questionnaire responses and open and axial coding. Some amendments were made to provisional themes and sub-themes at this stage. Finally, a literature review was then undertaken by the first author informed by the sub-themes on the topics of guided discovery, therapist skill development, therapist schemas and role transition. This informed the final selective coding phase which led to the integration of categories and sub-categories to arrive at a central concept which would drive the emerging theory.

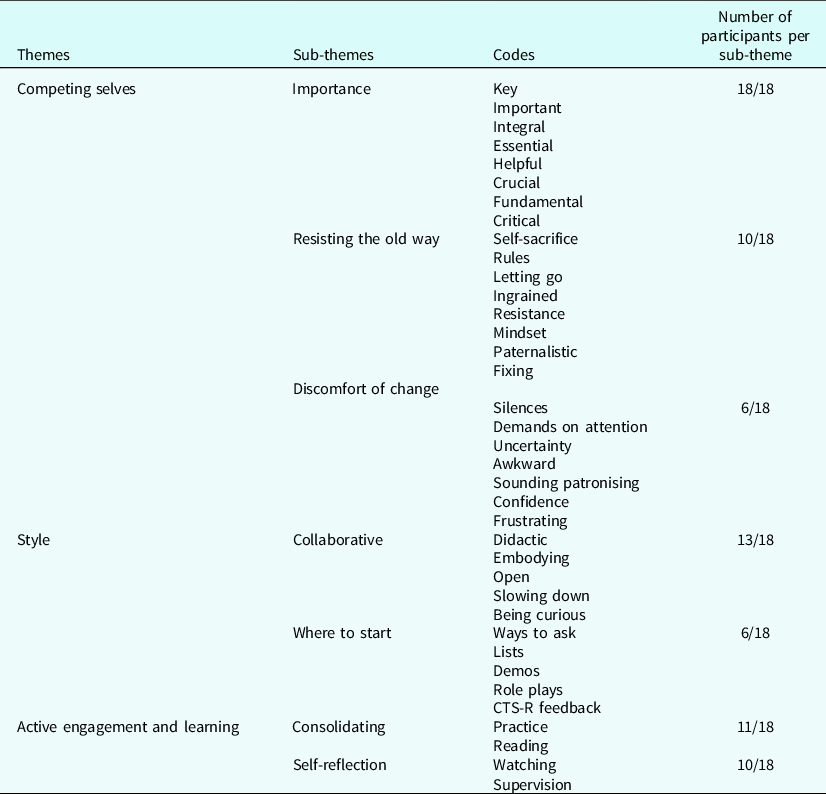

Results

Three main interconnected themes emerged along with seven sub-themes (see Table 4).

Table 4. Overview of themes

Theme 1: Competing selves

This theme captured what might be described as an ‘intrapersonal conflict’ amongst many of the participants. One of them (summarised in the sub-theme ‘Importance’), the one that wanted to become proficient in all aspects of CBT, knew the importance of GD and wanted to improve their theoretical knowledge and technical skills in this area. However, others (sub-theme ‘Resisting the old way’) resisted this approach as it seemed very alien to how they had previously interacted with clients and brought up uncomfortable thoughts and feelings (sub-theme ‘Discomfort of change’).

Sub-theme 1a: Importance

Several participants (P) commented on the crucial role that GD plays in helping clients to become their own therapist (P11: ‘I think it is an extremely important part of the process as the more the client reaches their own discoveries, the more in control they will feel in terms of addressing key issues’). There was also a sense that using GD would lead to more lasting changes, in contrast to the therapist trying to make connections for the client or to give them the answers to their problems:

‘That it is a crucial tool for meaningful change for a client – it seems that if a client can make their own discoveries instead of just being told something then they are more empowered and engaged in making long lasting changes.’ (P13)

Furthermore, this sub-theme revealed that all participants grasped the theoretical aims of GD as explained by P1:

‘I think it is the key to a collaborative alliance, it prevents assumptions being made on the therapist part.’ (P1)

Sub-theme 1b: Resisting the old way

Despite participants intellectually understanding the benefits to their clients of using GD (at a ‘head’ level), there was recognition of the personal and emotional challenges this raised for them as an inexperienced CBT practitioner (the ‘heart’); for example, struggling to let go of old behaviours which had been largely didactic (P1: ‘being didactic can be quite ingrained’). In addition, telling the client what to do in terms of making suggestions, advice giving, signposting or delivering psycho-education had been a significant part of the participants’ former roles. For some, the lack of clinical experience using GD was a barrier in the transition from a didactic approach in the sense that seeing was believing:

‘Initially I believe I was somewhat resistant to this approach as I did not fully understand how powerful this approach could be for clients in their understanding and learning long term. I believe my lack of experience in using this approach was a big challenge.’ (P8)

Resistance to adopting a GD approach to clinical work also appeared to be driven by dysfunctional therapist schemas. Certain types of responses from clients (e.g. behaving in a helpless or needy manner) could trigger difficult feelings where trainees felt compelled to rescue themselves and the client from the discomfort of sitting with uncertainty:

‘It’s also difficult when you feel they may be struggling as certain (common) schema then crop up such as the excessive self-sacrifice where the practitioner ends up doing more work in an effort to rescue people.’ (P11)

Overall, there was a recognition amongst participants that a shift in ‘mindset’ was required to address the ‘head–heart lag’. This would involve consciously letting go of old habits which had previously felt useful as P6 indicates:

‘The main challenges are adjusting to a completely new way of working when you are so used to a specific style. Changing your mindset and ensuring you make a conscious effort during sessions to keep GD at the forefront.’ (P6)

Sub-theme 1c: Discomfort of change

Some of the participants described the process of transitioning from their old role to CBT as evoking specific feelings of vulnerability, frustration and uncertainty. One’s emotional state could also influence the degree to which trainees adopted or committed to a GD style as P16, formerly a mental health nurse explained:

‘When a client has a tendency to become tangential or avoidant in their interactions and stray away from subjects. It can at times feel more difficult to master it in these situations. When a client is showing emotions such as anger or demonstrating they do not wish to talk. When I am feeling particularly burnt out or exhausted by a session.’ (P16)

Other therapy scenarios such as silences following a Socratic question triggered doubts about one’s confidence in their ability to be helpful to the client through GD. Several participants stated that they had previously filled these moments with advice giving:

‘As a PWP my role was to give advice and act as a “coach” to help clients make behavioural and cognitive changes. It felt much more didactic where I tended to tell clients which areas they were to focus on. There was not a lot of opportunity to elicit feedback it was more about giving it. Guided discovery on the other hand is about guiding the client to make their own discoveries through the use of Socratic questioning and feeling comfortable with silences to allow space for this.’ (P11)

Theme 2: Style

Theme 2 captured participants’ recognition of their style beginning to change, moving from that of an instructor, previously reliant on a didactic manner to one of ‘openness and curiosity’ where responsibility for change was shared with clients. However, there was a sense that ‘old habits die hard’ as they were still adjusting to having longer sessions and pacing was a skill that was also a work in progress.

Sub-theme 2a: Collaborative

Most of the participants were able to describe the characteristics of a GD style (P12: ‘embodying the attitude of openness and curiosity, as well as the skill of doing it’). Many of them also understood that GD helped to make therapy sessions more collaborative and had noticed tangible changes to their clinical practice:

‘I definitely do not “lecture” or “talk at” the client anywhere near as much as I did previously.’ (P18)

Conversely, some participants recognised that their previous professional roles continued to influence the level of responsibility that they apportioned to themselves for the direction of therapy, and this was as much a struggle for mental health nurses and assistant psychologists as it was for PWPs:

‘The onus being on the client to make discoveries with the help of the therapist rather than the therapist giving answers.’ (P14)

In order to embrace a truly collaborative approach to therapy, participants recognised that there were certain personal barriers that they needed to work through such as changing how they paced interventions. Past roles, especially that of PWP had demanded a quicker pace with shorter sessions and less overall sessions:

‘As a PWP you feel very much didactic in sessions due to the limited time you have in sessions.’ (P6)

Sub-theme 2b: Where to start

Many of the participants voiced an uncertainty about both the final destination of a Socratic dialogue with a client and the appropriateness of when to use a guided discovery approach and when to be more directive. One participant questioned the degree to which role play assisted in acquiring procedural skills in guided discovery:

‘I think this is a skill that is hard to role play because the questions we utilise are dependent on what our individual clients say to us. This makes it difficult to master the skill.’ (P12)

Some participants found that having a prompt sheet in a therapy session with them, assisted in knowing how to phrase questions.

‘Knowledge of helpful phrasing of questions, “I wonder if”, “what’s going on for you right now”, “what just happened there”, “I have noticed that xyz, do you mind if we explore that a little”, “I wonder if this might be helpful”, “what do you make of that”, etc.’ (P18)

However, being in the ‘conscious competence’ stage of skill development, P3 explained that there were competing demands for their attentional resources:

‘For me, pulling away from my previous more didactic role has been particularly difficult. The spirit of GD to me is having the natural curiosity about the client and it can be hard to implement that curiosity whilst learning GD as I feel that some of my attention is on what specific questions to ask, therefore I suppose one challenge has been accepting that there is no set plan with GD, we don’t know where that conversation will go, and that that feels a little unnerving as a trainee.’ (P3)

Theme 3: Active engagement and learning

The final theme captured participants’ intentions to build on what they had learned during the course and how they planned to operationalise this. Supervision featured heavily in participant responses as a mechanism for consolidating current knowledge and skills and to improve through the use of video feedback, supervisor modelling and role play.

Sub-theme 3a: Consolidating

After completing the course, many participants planned to actively engage with literature that has been written on GD, either recapping existing lecture materials and handouts or looking for other resources. One participant (P17) reflected that their attempts to find further reading material or related resources through recommendations from peers or more experienced CBT IAPT practitioners had not been fruitful:

‘I remember asking my Step 3 colleagues where I could find out more but they couldn’t provide any answers either. It was like the unicorn of the therapeutic world – we have all heard and talked about it, but no-one knew where to find it.’ (P17)

P4 suggested that trainees needed a ‘refresher’ on GD skills towards the end of the course, with it being discussed in the first module and not revisited in any detail afterwards. P13 revealed that a visual aid consisting of a list of common Socratic questions was helpful to have printed out and close to them during online therapy sessions as it was a constant reminder to incorporate a GD style:

‘Having a prompt sheet by the side of my laptop whilst working has been the most helpful to remind myself to avoid close or directive questioning and be more Socratic, or even as a reminder to just stay quiet and try not to jump in.’ (P13)

In contrast, for a few of the participants’ signs of ‘unconscious competence’ were starting to emerge (P17: ‘I feel I am able to use it more spontaneously rather than consciously thinking about it as the client is talking or glancing at lists of useful questions, but I also feel I have a long way to go’).

P3 highlighted the important role that high quality supervision can play through the supervisor modelling a Socratic style:

‘I also feel that my supervisor has explored some of my questions in supervision with GD, encouraging me to discover the answers. This has enabled me to experience what it’s like to be questioned in this way but has also been a further opportunity to observe GD, which has further contributed to my awareness/understanding of how it works.’ (P3)

Sub-theme 3b: Self-reflection

A considerable number of participants stated an intention to use self-reflection as a means of continuing to improve their skills in GD. This would be achieved through either recording and watching their therapy sessions post-qualification (P5: ‘Constant practice, and perhaps continuing to record sessions to aid my own learning’) or focusing on aspects of GD skill consolidation in supervision:

‘Supervision has guided me to use a more curious approach to questioning.’ (P15)

For some, there was an interest in continuing to use competence measures post-training such as the CTS-R:

‘Rating my videos against the CTSR – playing video clips in supervision – watching/participating in role play in supervision – reading work by Padesky (Reference Padesky1993).’ (P2)

P11 cautioned about the need to be aware of therapist ‘rules for living’ being activated and how this might adversely impact on their clinical practice:

‘I think that self-reflection is also an important part of the CBT training as without that, practitioners may not notice that certain rules are firing up and preventing them from engaging with important tools.’ (P11)

Unfortunately they did not expand on this to explain which clinical situations these rules would ‘fire up’ in, or provide examples of the rules (e.g. ‘I should/must’) that were relevant to them.

Comparison with existing literature

The first master theme ‘competing selves’ resonated with existing literature on topics including the concept of a ‘multi-mind’ (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Montague, Elander and Gilbert2021), role transition (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020), cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Reference Festinger1957), and the role of formal and informal self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) in therapist skill development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001).

The multi-mind

Firstly, the idea of there being different aspects of the self is not new to CBT as the extant literature is full of examples such as the OCD Bully (e.g. Bream et al., Reference Bream, Challacombe, Palmer and Salkovskis2017), child and adult selves (e.g. Arntz, Reference Arntz2012; Wild et al., Reference Wild, Hackmann and Clark2007), personal and therapist selves (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006) the self-critic, criticised self and perfect nurturer (e.g. Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009; Lee, Reference Lee2005) and modes such as ‘the detached protector’ (e.g. Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2006). Indeed Bell et al. (Reference Bell, Montague, Elander and Gilbert2021) describe the human mind ‘as a multiplex of motivations, emotions and cognitive competencies that give rise to conflict and distress’ (p. 2). The sub-themes ‘Discomfort of change’ and ‘Resisting old ways’ capture the essence of this intrapersonal conflict.

Role transition and cognitive dissonance

The term cognitive dissonance describes a state whereby a person experiences conflicting thoughts and motivations. Harmon-Jones and Mills (Reference Harmon-Jones, Mills and Harmon-Jones2019) state that due to the psychological discomfort that arises from cognitive dissonance it ‘motivates the person to reduce the dissonance and leads to avoidance of information likely to increase the dissonance’ (p. 3). Participants displayed signs of dissonance by their recognition of the benefits of using GD with clients yet simultaneously experiencing difficult emotions when trying to resist using previously valued behaviours. Not only this but trainees are usually moving from a role where they felt ‘unconscious competence’ to ‘conscious incompetence’ (Cannon et al., Reference Cannon, Feinstein and Friesen2010). Unlike the Wilcockson study, there were no counsellors in this research, but it is plausible that they might face the same challenges of having competing selves – their previous professional self and the emerging ‘CBT therapist self’.

Another feature that was not present in the data is what Wilcockson (Reference Wilcockson2020) described as an ‘excessive identification only with the aspects of CBT that fit with existing identity and practice’ (p. 1). Participants in the present study wanted to shed the skin of their previous professional self yet struggled with the emotions this stirred up. They also needed to break free from mindlessly repeating habitual patterns of relating to clients. This might suggest that trainees need to work more on their ‘reflection-in-action’ skills (Schon, Reference Schon1987) to be more mindful of their moment-to-moment decisions within therapy sessions and to increase their distress tolerance (e.g. to become more tolerant of uncertainty) rather than their overt resistance (Leahy, Reference Leahy2000; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001).

Self-practice/self-reflection

Consolidation of emerging GD skills (Theme 3, sub-theme 1) reiterated the suggestion from literature sources that there are minimal concrete examples and guidance to define GD in action. P17’s description of the scarcity of resources as ‘the unicorn of the therapeutic world’ suggests something almost out of reach for those wanting to refine their skills in this area. Whilst not a core component of IAPT CBT training curriculum, ‘formal’ SP/SR has been shown to assist therapist skill development in a broad range of areas (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2014) and should be considered in addition to more standard ways of learning (e.g. reading/using CT-SR, role-playing). Informal SP/SR, defined here as unstructured, short-term methods such as completion of the Therapist Schema Questionnaire (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001) might also assist trainees in recognising schemas likely to interfere with the use of GD (e.g. helplessness).

Development of a preliminary model

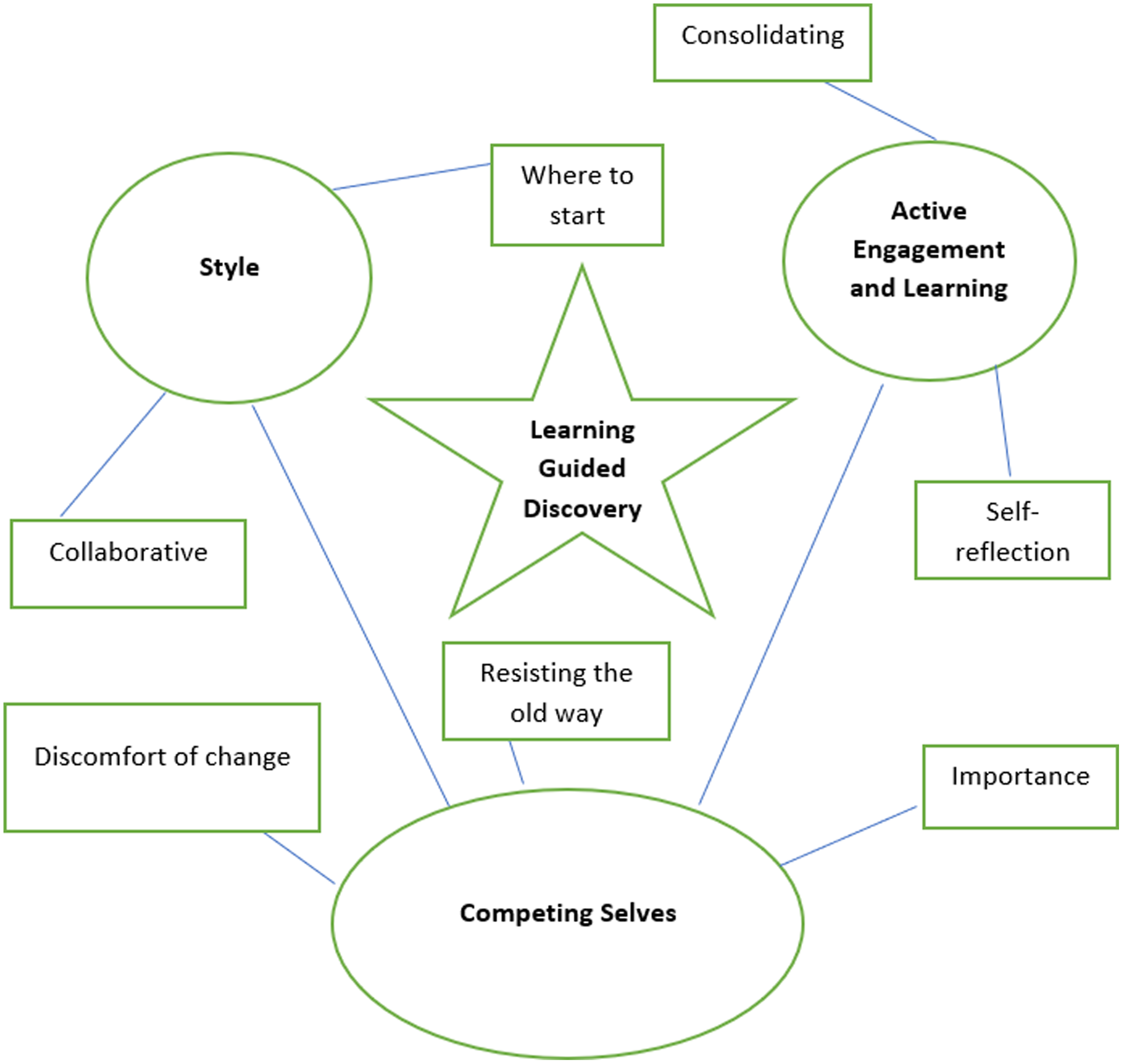

The next stage of data analysis involved the construction of a thematic map (see Fig. 2) to understand the relationships between themes.

Figure 2. Thematic map.

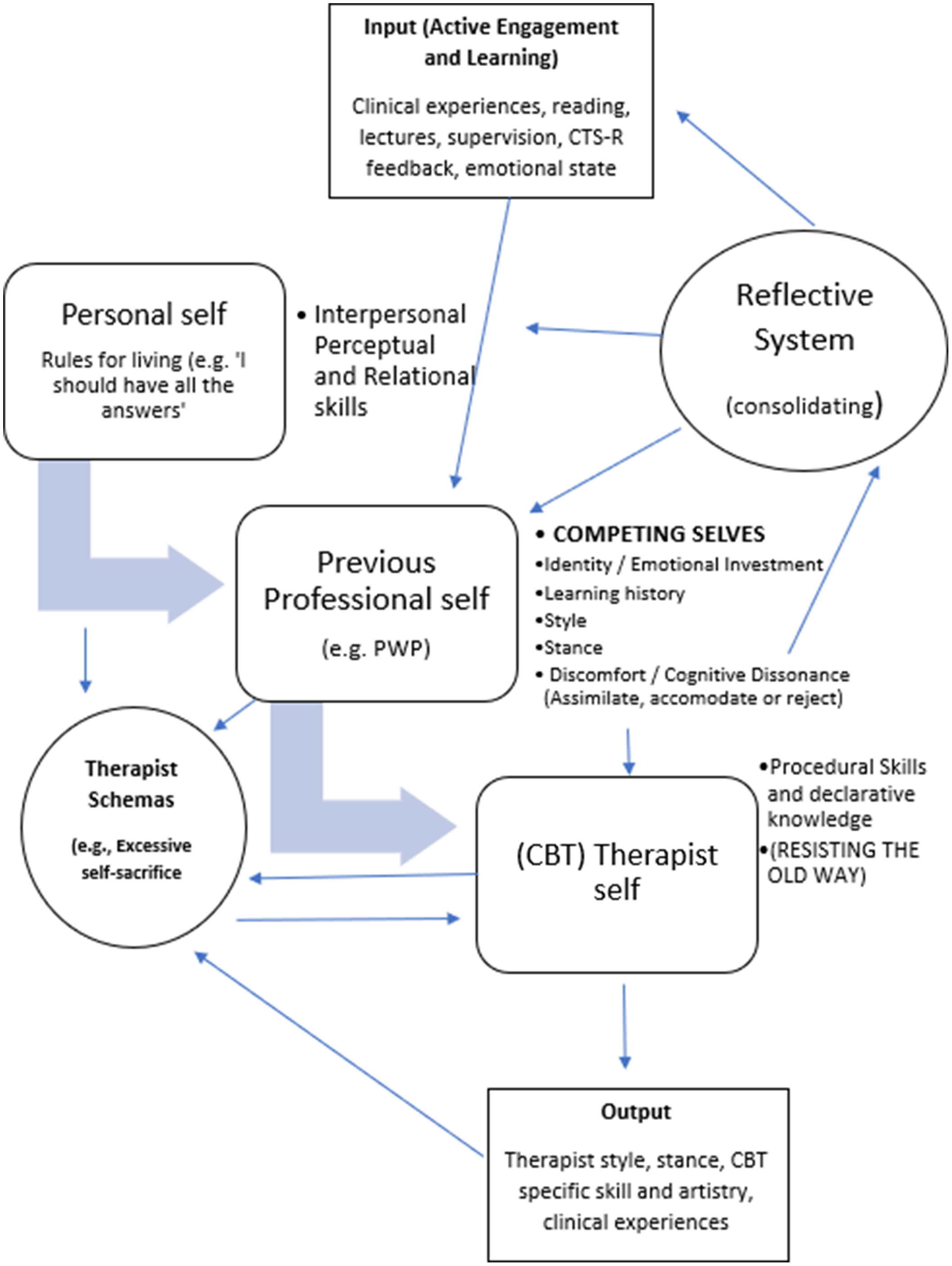

Birks and Mills (Reference Birks and Mills2015) suggest that three factors are necessary for the final stage of theory development in grounded theory (GT). The first is an identified core category. In this study, Theme 1 (Competing Selves) appeared to be central to changes or otherwise in therapist style and the process of ongoing attempts to improve their skills in the use of GD, as depicted by Fig. 2. An engagement with the relevant literature on multiple selves, therapist schemas and role transition led to a tentative model by the first researcher who asked the second and third researcher to check for face acceptability. In the later stages of the model’s development, it was presented to a new cohort of IAPT CBT trainees during the introductory module of their training to help them makes sense of role transition, in particular the contrast between guided discovery and more didactic ways of working that they had been used to. Explaining the model to students led to minor amendments to the content of the diagram following researcher reflection (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Preliminary grounded theory model of the factors that moderate CBT trainee skill development in the use of Guided Discovery (adapted from Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006).

Components of the model

Competing selves (personal self, previous professional self and CBT therapist self)

The model uses elements of Bennett-Levy’s declarative procedural reflective (DPR) model as a template on which to build. Relevant components will be discussed here; however, for a more detailed description of this model readers are directed to the 2006 seminal paper (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006). In his model of general therapist skill development and refinement, Bennett-Levy proposes the existence of a self-schema (later referred to as the ‘personal self’) and a self-as-therapist (‘therapist self’). The personal self contains all the trainee’s past learning including core beliefs, rules and assumptions and action tendencies. This ‘self’ influences the therapist self, which in turn influences the personal self. In the model illustrated in this paper it is hypothesised that a third ‘self’ competes with the emerging CBT therapist self. Trainees may already possess a ‘therapist self’ from another modality (e.g. person centred counselling) which in the new model is included in the ‘previous professional self’ category along with other professional roles such as mental health nursing, PWP, occupational therapist, clinical psychologist or social worker. Participant responses in the data and other relevant studies (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012; Wilockson, Reference Wilcockson2020) suggest that many trainees experience ‘intrapersonal conflict’ (Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020; p. 2), resulting in a phase of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Reference Festinger1957). This was characterised by feelings of discomfort as the new ‘declarative’ information they are exposed to in lectures, supervision, self-directed reading and clinical contact (the input) ‘competes’ with old knowledge and redundant behaviours (see Table 5). GD constitutes a very different way of approaching assessment, treatment and caseload management whereby trainees must consciously resist slipping into using tried and tested methods such as advice giving which might temporarily reduce unwanted feelings.

Table 5. Previous professional self and associated ‘redundant’ roles

Therapist schemas

Another addition to this new model is the inclusion of therapist schemas (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001) and the hypothesised role they could play in delaying skill development in areas such as GD. For example, a trainee might possess a ‘personal self’ rule ‘I should have all the answers’. This rule might have been reinforced in a previous role where advice giving was central (e.g. social work). This influences their ‘therapist self’ and translates to ‘I should have the solutions to all of my clients’ problems’. According to Leahy (Reference Leahy2001), this might indicate the presence of the Excessive Self-sacrifice schema (see also Farrell and Shaw, Reference Farrell and Shaw2017; Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2006). The activation of this schema in therapy would likely impede the trainee from utilising GD given the opposing style and stance that it requires. The cognitive dissonance is resolved once the trainee either assimilates, accommodates or rejects the new learning (Piaget and Cook, Reference Piaget and Cook1952) following a period of sharpening their procedural skills through client contact, self-reflection or addressing skills deficits in supervision. The model proposes that active and deliberate reflection is required to consolidate procedural skills in GD which can be assisted by supervision, self-directed reading and reviewing one’s style in recordings of therapy sessions.

Input and output

During CBT training, practitioners are exposed to numerous sources of learning (input) such as clinical encounters with clients, and lectures describing the concept and definition of GD. They are recommended to read specific papers (e.g. Padesky, Reference Padesky1993), book chapters (e.g. Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2017), to reflect on CTS-R feedback, to utilise supervision. The data also suggested that the trainee’s emotional state is likely to impact their ability to make use of GD with clients. Individual therapist variables such as burn-out and the complexity of the client in front of them are likely to affect emotional state and the opportunities to practise GD consistently. The output represents changes or otherwise to the trainee’s beliefs about how clients learn best, their style and their demonstrated level of skill in GD.

The reflective system

Described by Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) as the key to the ‘development of therapist expertise’ (p. 60), its role in his original model is to marry together declarative and procedural knowledge that is accrued during CBT training. Bennett-Levy explains: ‘Its function is to perceive differences: to compare and contrast present experience with past experience’ (p. 68). For example, the trainee practitioner will compare new conceptual, technical and procedural knowledge from lectures and supervision (e.g. the role of GD in CBT/Socratic questioning methods) with existing knowledge (e.g. being ‘helpful’/providing a client with advice). When faced with a clinical scenario (e.g. a client is unsure about whether to drop a safety behaviour), Bennett-Levy suggests that either old rules for how to respond in a clinical situation are followed (e.g. a PWP explains to the client how safety behaviours make their problem worse in the long run) or new rules accessed from declarative and procedural systems are created and followed (e.g. a cost-benefit analysis is proposed where the therapist adopts an impartial stance). In the model proposed in this paper, the reflective system plays a crucial role in helping the trainee to overcome the cognitive dissonance experienced through their role transition. The key difference is the hypothesised barriers to the incorporation of declarative and procedural knowledge, caused by the previous professional self (PPS). The PPS, in effect, functions as a gatekeeper between the input from clinical experience, lectures, supervision and other forms of learning and the output (therapist style, stance, CBT specific skill and artistry). The reflective system in the context of managing role transition would need to specifically target this cognitive dissonance which could be achieved through the use of SP/SR (e.g. completing thought records about one’s experiences of trying out GD in clinical practice) and identification and modification of dysfunctional therapist schemas (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001).

Discussion

Little was known about the order in which specific CBT skills and competences (e.g. Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Reichelt, Garland, Baker and Claydon2001; Roth and Pilling, 2008) are developed, which are the most challenging ones for trainees to learn and which trainees struggle the most with (Liness et al., Reference Liness, Beale, Lea, Byrne, Hirsch and Clark2019a; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2018; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020). Limited research in this area suggests that clinical psychologists adjust more quickly and achieve overall competence sooner than other trainees (Kjøge et al., Reference Kjøge, Turtumøygard, Berge and Ogden2015; McManus et al., Reference McManus, Westbrook, Vazquez-Montes, Fennell and Kennerley2010). In contrast, trainees without a core profession may lack confidence in comparison with peers, whilst nurses and counsellors face difficulties associated with emotional avoidance and loss (Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020). Irrespective of professional history, it is widely recognised that guided discovery is a particularly challenging skill for many trainees to master or for trainers to clearly define (Carey and Mullan, Reference Carey and Mullan2004; Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014; Kennedy-Merrick et al., Reference Kennedy-Merrick, Haarhoff, Stenhouse, Merrick and Kazantzis2008; Maruniakova and Rihacek, Reference Maruniakova and Rihacek2018; Waltman et al., Reference Waltman, Hall, McFarr, Beck and Creed2017). The aim of this research was twofold. Firstly, to gain a better understanding of how CBT trainees experience learning how to use one of the most vital skills with their clients (guided discovery). Due to the paucity of existing literature in this area, grounded theory lent itself well as a research methodology. The study revealed that participants had acquired sufficient declarative knowledge of GD by the end of the training yet struggled with their procedural skills (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006). Given that they are still early on in their CBT career this is understandable, and it could be reasonably hypothesised that more clinical hours might lead to improved procedural skills in GD.

One potential barrier to this is the impact that their ‘previous professional self’ and ‘personal self’ has on their receptiveness to change. Experimenting with a new way of working such as GD exposes the novice therapist to uncomfortable thoughts and feelings which could lead to avoidance if this is not addressed. Ongoing supervision and self-directed learning post-qualification are obvious solutions to this however, as P17 stated, for a skill that is so essential to the competent practice of CBT there have been very few practical examples (e.g. extensive vignettes, examples of how to phrase Socratic questions) of guided discovery within the extant literature to assist trainees in converting their declarative knowledge into procedural skills (for a rare example, see Wells, Reference Wells1997).

The second aim of the study was to develop a preliminary model of the processes that help or hinder the development of skills in guided discovery from participant responses. A preliminary model, adapted from Bennett-Levy’s DPR model (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) emerged incorporating constructs that may be relevant to role transition including therapist schemas (Leahy, Reference Leahy2001) and a ‘previous professional self’ that competes (Brewin, Reference Brewin2006) with the emerging ‘CBT therapist self’ when new information (e.g. concepts and ways of working) is presented. It is hoped that this model can inform CBT trainers and supervisors to help trainees normalise the difficulties that role transition raises for them.

Limitations of the study

There are several limitations in the results of this study. Firstly, the research was conducted with a single cohort across a single training institution therefore it is difficult to generalise the findings. Participant responses could have been influenced by the programme design (Kennedy-Merrick et al., Reference Kennedy-Merrick, Haarhoff, Stenhouse, Merrick and Kazantzis2008) such as the idiosyncratic nature of the lecture content delivery (e.g. tutor style), the supervision they were exposed to and the clients on their caseload (e.g. those who are more difficult to be Socratic with). Secondly, the relatively small number of trainees that took part (n = 18) and the high proportion of PWPs (n = 15) might not be representative of the themes which could emerge from a wider pool of responses including a broader range of prior professions (e.g. counsellors, clinical psychologists). Finally, from a methodological perspective, questionnaires do not allow for elaboration of responses in the way that semi-structured interviews do. The latter would have allowed the researcher to prompt participants to expand on their experiences and clarify vague statements.

Recommendations

Out of all the CBT competences, guided discovery may be particularly challenging as it involves not only the acquisition of technical knowledge (what it is) and procedural skill (how to use it and in what context) but also a perspective shift. GD is as much a stance towards therapy and towards how clients change as it is a style with defining questions (e.g. Wells, Reference Wells1997). The data revealed a range of clinical scenarios in which therapists would depart from GD, some of which were justifiable and some due to their own discomfort around the silences that might occur and a feeling of ‘awkwardness’ from engaging a client in Socratic dialogue. The findings in this study and in previous papers on role transition suggest that in times of uncertainty, trainees may revert to using safety seeking behaviours (e.g. methods from their previous job role; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020).

Managing intrapersonal conflict

Wilcockson (Reference Wilcockson2020) points out that ‘the integration of personal and professional selves is not typically part of the CBT curriculum. It is difficult to teach but requires awareness from lecturers and supervisors’ (p. 13). ‘Role transition anxiety’ and the associated intrapersonal conflict could be specifically addressed early on within CBT training courses using the new model through didactic teaching, discussion in supervision or through formal SP/SR (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012) and more informal methods such as the therapist schema questionnaire (Leahy, Reference Leahy2001). This tool has been used in CBT training to assist in developing awareness and could be a useful way to open a dialogue with trainees about the role that our own beliefs play in CBT skill development (see Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006).

Existing research also suggests that trainee CBT practitioners perceive supervision to have the greatest impact on the development of their clinical competence (Kennedy-Merrick et al., Reference Kennedy-Merrick, Haarhoff, Stenhouse, Merrick and Kazantzis2008; Rakovshik and McManus, Reference Rakovshik and McManus2013) and that they are receptive to exploring their own therapy interfering beliefs within supervision (Roscoe, Reference Roscoe2021a). The intrapersonal conflict experienced by trainees could be addressed in supervision through experiential methods which engage with the concept of ‘multiple selves’ (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Montague, Elander and Gilbert2021). For example, chair work (see Roscoe, Reference Roscoe2021b for an example of how a therapist can work through their own blocks). Operationalising the concept of ‘self-multiplicity’ (Pugh, Reference Pugh2019) early in CBT training and supervision is an established way of normalising the discomfort of change and the ubiquity of ambivalence (Pugh and Salter, Reference Pugh and Salter2018). Chair work also provides a tangible means of noticing and naming the competing motivations of different parts of the self (e.g. the previous professional self and the CBT therapist self) (Pugh and Bell, Reference Pugh and Bell2020). It should be recognised that CBT tutors and supervisors may lack sufficient declarative and procedural knowledge in the use of chair work, identification of intrapersonal processes or managing role transition and therefore specific training may be required before introducing this to trainees (Pugh et al., Reference Pugh, Bell, Waller and Petrova2021). In these instances, trainees can also be directed to SP/SR workbooks which may assist them in recognising and working through problematic schemas and rules that may arise during training (see Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2014; Farrell and Shaw, Reference Farrell and Shaw2017).

Improving overall skills in GD during training

The data revealed that more conventional supervision and teaching methods are still highly valued by trainees, namely observing and then engaging in role play or ‘real-play’, reading seminal papers (e.g. Padesky, Reference Padesky1993) and watching recordings of their own or expert practitioner therapy sessions. Several participants stated that GD needed to be practised more frequently throughout the course, therefore in addition to incorporating this formally within the curriculum, it is suggested that tutors and supervisors should model the use of Socratic dialogue where possible so that trainees can experience what it is like to be on the receiving end of this and to regularly hear how qualified and experienced CBT practitioners phrase questions. Finally, it would be interesting to see what difference it would make to formally incorporate the Padesky (Reference Padsesky2020) Socratic Dialogue Rating Scale & Coding Manual into the course module content.

Future research

Future research might look to explore qualified, experienced CBT practitioners’ use of and attitudes towards GD. The intrapersonal conflict between previous professional self and CBT therapist self might not be resolved during training and may continue to impact CBT practitioners further in their career. Indeed, it may represent a ‘sunk cost commitment’ where a therapist will resist letting go of old ways of working due to the amount of time and energy that have previously been invested (Leahy, Reference Leahy2000; Leahy, Reference Leahy2001). Other research avenues include understanding how GD skill development is supported in the workplace post-qualification (Kennedy-Merrick et al., Reference Kennedy-Merrick, Haarhoff, Stenhouse, Merrick and Kazantzis2008). For example, Kjøge et al. (Reference Kjøge, Turtumøygard, Berge and Ogden2015) found that upon course completion, trainees in Norway ‘were not sufficiently supported in the transition from training to practice’ (p. 12). Finally, it would be useful to investigate how adaptable the model is to different aspects of CBT skill development. For example, the model within this paper has also been used informally to explore another key aspect of CBT – agenda setting (AS) with a more recent cohort of trainees. The hypothesised components of the model appear to translate easily from the blocks that inhibit skill acquisition in GD to those that affect AS. In terms of specific factors to explore, it might be useful to explore the role that intolerance of uncertainty and self-esteem play in this behaviour as these have been shown to affect other aspects of CBT clinicians’ behaviour (see Simpson-Southward et al., Reference Simpson-Southward, Waller and Hardy2018 in relation to CBT supervision).

Key practice points

-

(1) Trainee CBT practitioners may have a technical understanding of guided discovery by the end of their course but often struggle with how and when to use it clinically.

-

(2) Pre-existing professional identities and beliefs about the role of the therapist and the responsibility and agency of the client produce an intrapersonal conflict which could have an impact on the degree to which they use guided discovery.

-

(3) Further research is needed to understand specific cognitions and emotions that are associated with an avoidance or under-utilisation of guided discovery in trainee and qualified CBT practitioners.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the trainees from the 2020 cohort that took part in this research.

Author contributions

Jason Roscoe: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (lead), Supervision (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Elizabeth Bates: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Supervision (supporting); Rhiannon Blackley: Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

The authors received no funding for this piece of research.

Conflicts of interest

The first and third authors are tutors and supervisors on the IAPT CBT training course on which participants for this research were enrolled. The second author has no conflicts of interest with respect to this paper.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical approval was granted by University of Cumbria reference number 20/01.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.