Individuals with severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder have a reduced life expectancy compared with the general population, especially related to cardiovascular disease. Reference Brown, Barraclough and Inskip1-Reference Sukanta, Chant and McGrath3 Furthermore, this gap has increased in recent years, especially with regard to schizophrenia Reference Sukanta, Chant and McGrath3,Reference Brown4 and bipolar affective disorder. Reference Brown4 The standardised mortality ratio for death within 1 year of psychiatric in-patient care for people with schizophrenia increased from 1.6 in people discharged in 1999 to 2.2 in those discharged in 2006, and for people with bipolar disorder it increased from 1.3 in 1999 to 1.9 in 2006. Reference Hoang, Stewart and Goldacre5 The aetiology of this excess cardiovascular disease is multifactorial and most likely includes genetic and lifestyle factors as well as disease-specific and treatment effects. Reference De Hert, Dekker, Wood, Kahl, Holt and Möller6

People with severe mental illness are likely to have a number of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors. The metabolic syndrome is a constellation of cardiovascular risk factors that helps to identify individuals at risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. It comprises a combination of physical and metabolic abnormalities which can be identified by abnormal values for: central obesity, hypertension, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting plasma glucose. Reference Alberti, Zimmet and Shaw7 These abnormal clinical and metabolic findings act to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. It has been consistently shown that there is an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in people with psychotic illness, with one large study reporting that 52% of individuals in a population of psychiatric out-patients met the US National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) criteria for metabolic syndrome. Reference Khatana, Kane, Taveira, Bauer and Wen-Chih8 In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, over 30% of patients met the NCEP ATP III criteria for metabolic syndrome at baseline. Reference Daumit, Goff, Meyer, Davis, Nasrallah and McEvoy9

Weight gain is a well-established side-effect of antipsychotic medication, in particular certain second-generation antipsychotic medications. The cumulative incidence of patients becoming overweight on clozapine exceeds 50%, with a mean weight gain of 4.45 kg at 10 weeks of treatment, Reference Umbricht, Pollack and Kane10 and a mean weight gain of 4.15 kg for olanzapine and 2.1 kg for risperidone. Reference Allison, Mentore, Heo, Chandler, Cappelleri and Infante11 There is an increased risk of dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, hyperglycaemia and new-onset type 2 diabetes, and this risk is particularly associated with the use of olanzapine and clozapine. Reference Akhtar, Kelly, Gallagher and Petrie12-Reference Gumber, Abbas and Minajagi16

The need for screening and monitoring cardiovascular risk factors in psychiatric populations is well documented, however, the evaluation of screening practices by clinicians has been shown to be suboptimal. Reference Correll, Druss, Lombardo, O'Gorman, Harnett and Sanders15,Reference Gumber, Abbas and Minajagi16 In this study, we sought to ascertain the prevalence and associations of metabolic syndrome in a typical cohort of individuals with chronic enduring mental illness attending the psychiatric day centres within a catchment area mental health service. We wished to evaluate whether there was an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in individuals on antipsychotic medication, on high-dose antipsychotics and on antipsychotic polypharmacy. We also sought to assess the prevalence of the individual metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease in our study population and the extent to which they were being screened for.

Method

Participants who lived in the community and who were attending one of the three psychiatric day centres in the West Galway adult mental health services were recruited over a 4-week period in July 2011. Two of the day centres were located in an urban setting and the third was in a rural setting. All of the 136 individuals who were attending any of the three centres over that period were asked to participate. Completed data were obtained from 100 patients (73.5%) and included in the study; 36 individuals were not included in the study, as complete anthropomorphic data could not be obtained from them.

Diagnoses were made in accordance with ICD-10 diagnostic criteria from clinical interviews and review of the medical notes. 17 Clinical and demographic data including age, gender and ethnicity were collected from each individual. Treatment with high-dose antipsychotic medication was defined as receiving more than 100% of the British National Formulary maximum dose per day. 18 For patients on more than one medication, this was calculated by converting their prescribed dose to its percentage of the maximum recommended dose for each drug and then summing the percentages. Reference Yorston and Pinney19

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) definition of metabolic syndrome Reference Alberti, Zimmet and Shaw7 (Table 1) was used. In addition, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) >6% was used to indicate impaired fasting glucose and was deemed to meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome. Reference Yorston and Pinney19 This was applied to individuals who had blood drawn by their general practitioners (GPs) in the previous 12 months and who were screened with an HbA1c level rather than with a fasting plasma glucose level (n = 16).

TABLE 1 Diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome used in the study

| Risk factor | Defining measure |

|---|---|

| Central obesity | Waist circumference |

| Men | ⩾94 cm for Europid men, ⩾90 cm for South Asian men |

| Women | ⩾80 cm for Europid women, ⩾80 cm for South Asian women |

| Plus any two of the following: | |

| raised triglycerides | ⩾1.7 |

| OR specific treatment for this lipid abnormality | |

| reduced HDL cholesterol | |

| men | <1.03 |

| women | <1.29 |

| OR specific treatment for this lipid abnormality | |

| raised blood pressure | Systolic ⩾130 mmHg or diastolic ⩾85 mmHg |

| OR treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension | |

| raised fasting plasma glucose | ⩾5.6 mmol/l |

| OR previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Reproduced with permission from Alberti et al. 6 B International Diabetes Federation.

The medical records (both hospital and primary care) of these individuals were examined for evidence of measurement of fasting glucose, HbA1c, triglyceride or HDL cholesterol levels. Those who did not have these parameters assessed in the previous 12 months had morning blood samples drawn after a period of fasting of at least 12 h and tested for: fasting plasma glucose, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and HbA1c.

Although anthropomorphic measurements such as body mass index (BMI) could be derived from some of the patients’ notes, this information was often insufficient for the purposes of diagnosing metabolic syndrome (e.g. few patients had a documented waist circumference). Therefore, all patients were assessed for anthropomorphic measurements for the present study. Height, weight and waist circumference were all measured using standardised techniques. The waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the lower rib and the iliac crest with the patient standing. Standardised techniques were used to measure blood pressure. A medical history was obtained from each individual and included items such as psychiatric history, medical history (including hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia), medication, family history (including ischaemic heart disease), smoking and exercise habits.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 18.0 for Windows. The student t-test for parametric data and the χ2-test for non-parametric data were employed. All statistical tests were two-sided and the α-level for statistical significance was 0.05.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 58 years (s.d. = 12.3) and 55% of the study population were female. Most patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (50%), recurrent depressive disorder (31%) and bipolar affective disorder (9%). Overall, 85% of participants were treated with antipsychotic medication, with 79% of patients taking atypical antipsychotics, most frequently olanzapine (34%), quetiapine (23%) and clozapine (9%). In total, 63% of patients were treated with atypical antipsychotic monotherapy and 6% were treated with typical antipsychotic monotherapy; 16% were on a high-dose antipsychotic and 32% were taking more than one antipsychotic.

Fifty-five patients (55%) met the IDF criteria for metabolic syndrome. The clinical characteristics of patients with and without the metabolic syndrome are presented in Table 2. Relatively more women than men met the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.089). There was no difference in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome by psychiatric diagnosis. The means of most metabolic parameters were significantly elevated in those patients fulfilling criteria for the metabolic syndrome. However, the mean total cholesterol levels were significantly lower in the group of patients with the metabolic syndrome than in those without the metabolic syndrome, presumably because 40% of individuals with the syndrome were on statin therapy, compared with 13% without metabolic syndrome on statin therapy.

TABLE 2 Demographics and clinical characteristics of individuals with and without metabolic syndrome

| Metabolic syndrome (n =55; 55%) |

No metabolic syndrome (n =45; 45%) |

χ2-test | d.f. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean | 59.7 | 56.8 | 1.163Footnote a | 98 | 0.255Footnote a |

| (s.d.=12.4; range 26-90) | (s.d.=12.2; range 34-87) | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 20 (45.5) | 24 (54.6) | |||

| Female, n (%) | 35 (62.5) | 21 (37.5) | 2.893 | 1 | 0.089 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||||

| Schizophrenia | 26 (52) | 24 (48) | 0.364 | 1 | 0.564 |

| Depression | 18 (58.1) | 13 (41.9) | 0.170 | 1 | 0.680 |

| Bipolar disorder | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | 0.01 | 1 | 0.972 |

| Other non-psychotic disorder | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | 0.112 | 1 | 0.738 |

| Treatment, n (%) | |||||

| Antipsychotic | 46 (54.1) | 39 (45.9) | 0.178 | 1 | 0.673 |

| Typical antipsychotic monotherapy | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 0.064 | 1 | 0.800 |

| Atypical antipsychotic | 43 (54.4) | 36 (45.6) | 0.049 | 1 | 0.08 |

| Antipsychotic polypharmacy | 16 (50) | 16 (50) | 0.475 | 1 | 0.491 |

| High-dose antipsychotic | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.8) | 4.341 | 1 | 0.043 |

| Clozapine | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | 2.073 | 1 | 0.150 |

| Olanzapine | 21 (61.8) | 13 (38.2) | 0.952 | 1 | 0.329 |

| Smoking, yes | 25 (58.1) | 18 (41.8) | 1.211 | 2 | 0.546 |

| Exercise >3×20 min/week | 19 (45.2) | 23 (54.8) | 2.760 | 1 | 0.071 |

| Family history of CVD | 21 (52.5) | 19 (47.5) | 0.168 | 1 | 0.682 |

| Family history of diabetes | 13 (61.9) | 8 (38.1) | 0.512 | 1 | 0.47 |

CVD, cardiovascular disease.

a. Independent sample t-test.

Overall, 54% of patients on atypical antipsychotics, 50% of those on antipsychotic polypharmacy and 31% of those on high-dose antipsychotic medication met the criteria for metabolic syndrome; however, there was no statistically significant association between each of these variables and the metabolic syndrome. Indeed, those taking high-dose antipsychotic medication were actually less likely to have metabolic syndrome. Most of the patients taking clozapine (78%) or olanzapine (62%) met the criteria for metabolic syndrome, although this was not a statistically significant association. Eleven per cent of individuals were on antidepressant monotherapy and 64% (n = 7) of those patients met the criteria for the metabolic syndrome.

The proportion of the sample, divided by gender, which met each of the individual criteria for metabolic syndrome is displayed in Table 3: 88% of individuals met the criteria for central obesity, 41% for hypertension and 43% for hypertriglyceridaemia. There were 32% of individuals with evidence of glucose dysregulation (impaired glucose tolerance or undiagnosed diabetes mellitus, or diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, or HbA1c >6%). Reference Nathan, Balkau, Bonora, Borch-Johnsen, Buse and Colagiuri20 This is in contrast to the figure of 14% for previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus in our study population. Whereas 28% of our study population were on treatment for hypercholesterolaemia and 33% were on anti-hypertensive medication, 47% of patients with metabolic syndrome were being treated with anti-hypertensive medication.

TABLE 3 Participants who met individual criteria for metabolic syndrome

| n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male (n = 44) | Female (n =56) | χ2 | d.f. | P Footnote a | |

| Metabolic syndrome | 55 | 20 (43.5) | 35 (62.5) | 2.893 | 1 | 0.089 |

| Central obesity | 88 | 36 (81.8) | 52 (92.8) | 2.843 | 1 | 0.092 |

| Hypertension | 41 | 16 (36.4) | 25 (44.6) | 0.833 | 1 | 0.362 |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 43 | 20 (45.5) | 23 (41.1) | 0.216 | 1 | 0.642 |

| Low HDL | 29 | 11 (25) | 18 (32.1) | 0.506 | 1 | 0.477 |

| Glucose dysregulation | 32 | 14 (21.8) | 18 (32.1) | 0.070 | 1 | 0.936 |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

a. χ2-test between males and females.

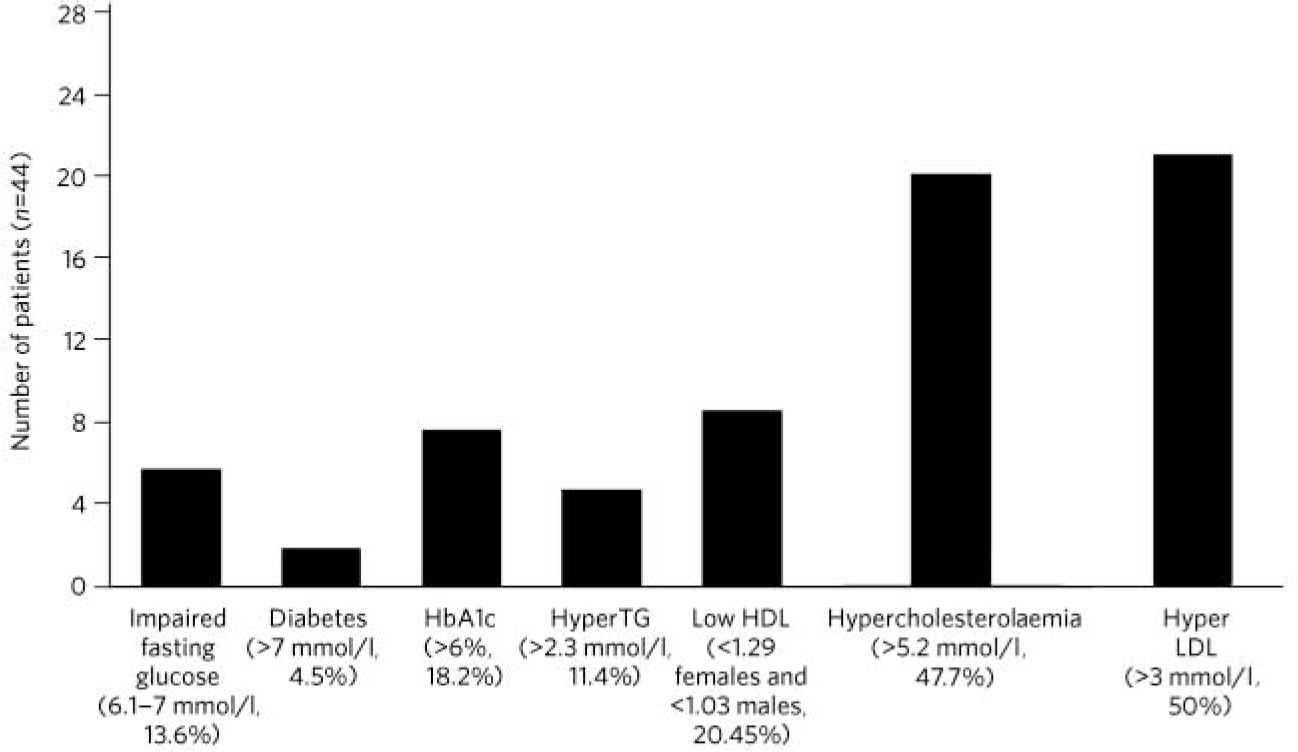

A substantial proportion (44%) of the individuals in this study had not been monitored for metabolic parameters in the previous year and this included 35% of the total population who were taking antipsychotic medication (Fig. 1). This cohort of unscreened individuals had a prevalence rate of 43% for the metabolic syndrome, with 30% identified with glucose dysregulation, including two new cases of diabetes mellitus. The rate of dyslipidaemia was greater than 50% in these individuals.

FIG. 1 Rates of metabolic abnormalities of patients who were not monitored for metabolic risk factors. HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HyperTG, hypertriglyceridaemia; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Discussion

There was a high prevalence rate of metabolic syndrome in this typical cohort of individuals with chronic enduring mental illness attending day centres within the catchment area service. Over half of these individuals (55%) met the criteria for metabolic syndrome, which is over twice the prevalence in the general Irish population. Reference Villegas, Perry, Creagh, Hinchion and O'Halloran21 This prevalence rate is similar to a previous study which examined patients on clozapine therapy and identified 46% prevalence rate for the metabolic syndrome. Reference Ahmed, Hussain, O'Brien, Dineen, Griffin and McDonald22

There was a similar prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with a history of non-psychotic disorders and those with a history of psychotic disorders. This study sample is representative of a typical cohort of patients with chronic enduring mental illness and there is a significantly elevated prevalence of the metabolic syndrome across a broad range of psychiatric disorders. This pattern of metabolic syndrome existing across psychiatric disorders has been reported in other studies. Reference Daumit, Goff, Meyer, Davis, Nasrallah and McEvoy9,Reference Mackin, Bishop, Watkinson, Gallagher and Ferrier23,Reference Vinberg, Madsen, Breum, Kessing and Fink-Jensen24 This study provides further evidence that chronic enduring mental illness in general should be considered a risk factor for metabolic syndrome. A similar prevalence rate of metabolic syndrome (using the IDF criteria) of 51% in patients with schizophrenia was reported elsewhere Reference John, Koloth, Dragovic and Lim25 and has been replicated in other studies such as the finding of a prevalence rate of 49% in individuals with a duration of schizophrenia of more than 20 years. Reference De Hert, van Winkel, Van Eyck, Hanssens, Wampers and Scheen26 The high rate of metabolic syndrome in our study regardless of diagnostic group or the use of antipsychotic medication indicates that it is chronic mental illness per se which is associated with metabolic syndrome rather than a psychotic diagnosis or the use of atypical antipsychotic medication. This may be due to the poor self-care associated with this patient cohort, including unhealthy diet and sedentary lifestyle.

Our study demonstrated similar prevalence rates of the metabolic syndrome in individuals treated with antipsychotics (54%) and those not on antipsychotic medications (46%). This is similar to other studies which showed prevalence rates of 48% for the metabolic syndrome in individuals treated with antipsychotics. Reference Krane-Gartiser, Breum, Glümrr, Linneberg, Madsen and Køster14

Strengths of the study are the screening of a cohort attending day centres in a catchment area service and thus representative of patients with chronic enduring mental illness in the region, rather than confined to a particular diagnosis or type of medication.

Limitations of the study include the cross-sectional design and the lack of a non-medicated control group or longitudinal assessment. This study did not assess the severity of symptoms, which may have been a contributing factor to the presence of the metabolic syndrome. Other confounding factors which may act as independent risk factors for metabolic syndrome (e.g. poor diet) were not assessed in this study population.

Despite the high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic enduring mental illness, such patients are likely to suffer from a fragmented and inconsistent approach to their physical healthcare. It has been identified that people with long-term mental illness tend to seek medical attention only in crisis situations and have limited access to general healthcare, with less opportunity for cardiovascular disease risk screening and prevention. Reference Kendrick27 This, allied to the high rates of metabolic syndrome in this cohort, highlights the need for improved integration in the screening for and management of physical risk factors. It is particularly important to improve the collaboration between primary and secondary care in the clinical care of these individuals. A recent study by our group has indicated that the majority of GPs were willing to take over the medical management of metabolic dysregulation emerging from antipsychotic prescribing in secondary care. Reference Bainbridge, Gallagher, McDonald, McDonald and Ahmed28 Given the high prevalence of metabolic risk factors in individuals with chronic enduring mental illness regularly attending mental health services, it is important that mental health services take advantage of the opportunity to improve their care by implementing protocols for the screening, pharmacological (including alteration of psychotropic medication) and non-pharmacological management of these risk factors and referral to primary or secondary care as required. As a minimum, individuals who are treated with antipsychotics should be systematically screened according to guidelines. Reference De Hert, Vancampfort, Correll, Mercken, Peuskens and Sweers29 The results of this study which showed high prevalence rates for metabolic syndrome across a range of psychotic and affective disorders indicates that it could be beneficial to extend such guidelines to the wider cohort of patients with chronic enduring mental illness. Twenty-five patients with metabolic syndrome in our cohort smoked (45.5%). Effective smoking cessation programmes would be an important intervention in reducing this particular cardiovascular risk factor.

A recent systematic review demonstrated that there is a paucity of research on the impact of general physical health advice on the outcomes of physical health awareness or physical health behaviour in people with serious mental illness. Reference Tosh, Clifton and Bachner30 There is a general consensus that physical activity has a mild to moderately favourable effect on many metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors that constitute or are related to metabolic syndrome. Reference De Hert, Schreurs, Vancampfort and Van Winkel31 This is supported by our study which demonstrated that 55% of individuals who exercised for more than 20 min at a time on more than three occasions in a week did not meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome. Physical health and diet educational programmes as non-pharmacological interventions for weight gain and other metabolic abnormalities should be implemented in the community setting. Reference Holt, Abdelrahman, Hirsch, Dhesi, George and Blincoe32,Reference Evans, Newton and Higgins33 This will involve initiation of programmes which can be adapted to the individuals’ personal preferences and their personal attitudes towards physical exercise and dietary restrictions.

The high prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in those with a history of chronic enduring mental illness indicates that this population would benefit from regular screening for and the intensive management of cardiometabolic risk factors to reduce their morbidity and mortality secondary to cardiovascular disease.

Funding

Research Support Fund, National University of Ireland, Galway.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and patients of the Ceim Eile and Danesfield psychiatric day centres in Galway city and the staff and patients of the Elm Tree Centre, Clifden, Co. Galway for their assistance in the completion of this study. We thank Mr Ben Kanagaratnam for his advice on the statistical analyses.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.