Introduction

The literature on wages and family budgets in contemporary rural Europe has not yet analysed real wages when taking into account the wages of men, women, and children in the long term. Not much is known of the wage differential between men and women, and even less of the contribution that women’s wages made to family income. Recent studies have advanced the literature about unskilled rural women’s wages from the Middle Ages to the nineteenth century (Humphries and Weisdorf, 2015). Some studies have considered not only wages but also life cycles. For instance, using family reconstruction of twenty-six English parishes, Schneider shows how the changing size and composition of individual families affected their welfare over the family cycle (Schneider, Reference Schneider2013). In the Netherlands, a recent life cycle study demonstrates that annual wages of men in agriculture and textiles were high enough to sustain their families at the subsistence level (Boter, Reference Boter2020). A recent study evaluates real household incomes of predominantly rural working families of various sizes and structures in England in the years 1260–1850. The article includes women and children’s contributions to family incomes, providing a novel framework within which to evaluate real household incomes.

In Spain, agricultural wage series rarely include women. We have some local series for Palencia (Moreno, Reference Moreno Lázaro2002); Navarra (Lana, Reference Lana Berasaín2007); Barcelona and Lerida (Garrabou, Pujol and Colomé, Reference Garrabou and Andreu1991). For the service sector, the research of Llopis and García Moreno (Reference LLopis and García Montero2011) and Drelichman and González Agudo (Reference Drelichman and Monteagudo2020) have provided some wage series. Spanish rural families had different sources of income because men’s wages alone were insufficient to cover families’ economic needs (Borderías and Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Borderías Modejar and Muñoz-Abeledo2018; Borderías, Muñoz-Abeledo and Cussó, Reference Borderías Mondejar, Muñoz-Abeledo and Xavier2022). Recent research reconstructs the wages of wet nurses over the long term (eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) for all regions of Spain, showing the importance of the wet nursing wages for family economies (Sarasúa, Reference Sarasúa2021).

This article focuses on changes in the labour markets of Galicia’s service sector during the nineteenth century, emphasising the importance of wet nurses’ income for rural family economies. Taking our previous research (Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo2021) as its starting point, it considers the spatial distribution of women employed in a key service sector occupation – wet nurses who worked for Galician foundling hospitals.

Work options for women in rural Galicia

Galicia is a region in the north-western Iberian Peninsula that encompasses approximately 6 per cent of Spain’s territory. Between 1787 and 1887, it was characterised by weak urbanisation, with only about twenty cities and small towns, a settlement pattern that was most dense in coastal districts, and a population that was 12–13 per cent of Spain’s total. About 80 per cent of Galicians practiced subsistence agriculture on small farms (1.3 to 2.7 hectares, on average), which, in addition, required exploitation of surrounding scrubland, maintenance of small livestock holdings, and complementary seasonal or short-term migration to Castile or Portugal – or long-term or definitive migration to America. This was a world in which peasant families played an unquestionably important historical role, and from whose lowest strata would emerge, as in the rest of Europe, the greatest number of women who worked as wet nurses (Bardet and Faron, Reference Fonte2005: 144; Fuchs, Reference Fuchs1984: 188; Fonte, Reference Fonte2005: 370; Cavallo, Reference Cavallo1983: 402–05).

In earlier work, we showed how a labour market for these wet nurses gradually developed between 1777 and 1822 (Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo2021). This was possible due to three factors. First, between 1777 and 1816, a system of six foundling hospitals was established in the region’s periphery. The aim was to complement the reception and attention given to foundlings by the Royal Hospital of Santiago de Compostela since 1524. Second, wages paid to external wet nurses of the new foundling hospitals were improved relative to the wages paid by the old Royal Hospital to its wet nurses. Third, the benevolence laws (1822, 1836, 1849) of the nascent liberal state, which helped professionalise the occupation, were implemented.

Still, the wages paid by Galician foundling hospitals were the lowest in Spain (Sarasúa, Reference Sarasúa2021: 470–82). This was because most of the hospitals established between 1777 and 1816 were small and experienced continual funding difficulties. Also, domestic production played an important role in peasant households, which allowed hospitals to offer lower wages than otherwise would have been acceptable. Finally, women in the countryside had few work alternatives. This was especially true after 1820–30, when domestic service and the rural textile industry offered few job opportunities.

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, an important labour market for domestic service existed in certain areas of rural Galicia. For example, in the bishopric of Lugo, located in Galicia’s interior, men and women servants worked in 23 per cent of households throughout the second half of the eighteenth century. Indeed, the job occupied 7–8 per cent of the bishopric’s residents. Fifty-five per cent of these servants were women from the lower strata of peasantry. Forty-six per cent of rural servants found work in the homes of small local nobility and parish clergy, which together comprised 10 per cent of the households of Galicia’s interior, while 48 per cent were contracted by peasant families, which made up 76 per cent of rural households (Dubert, Reference Dubert2005: 20–1).

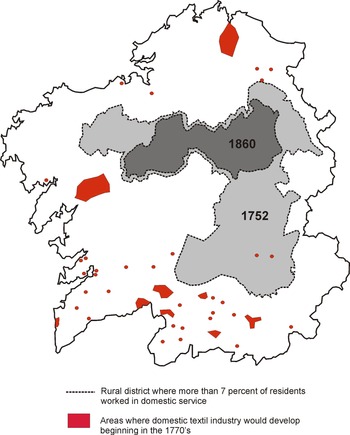

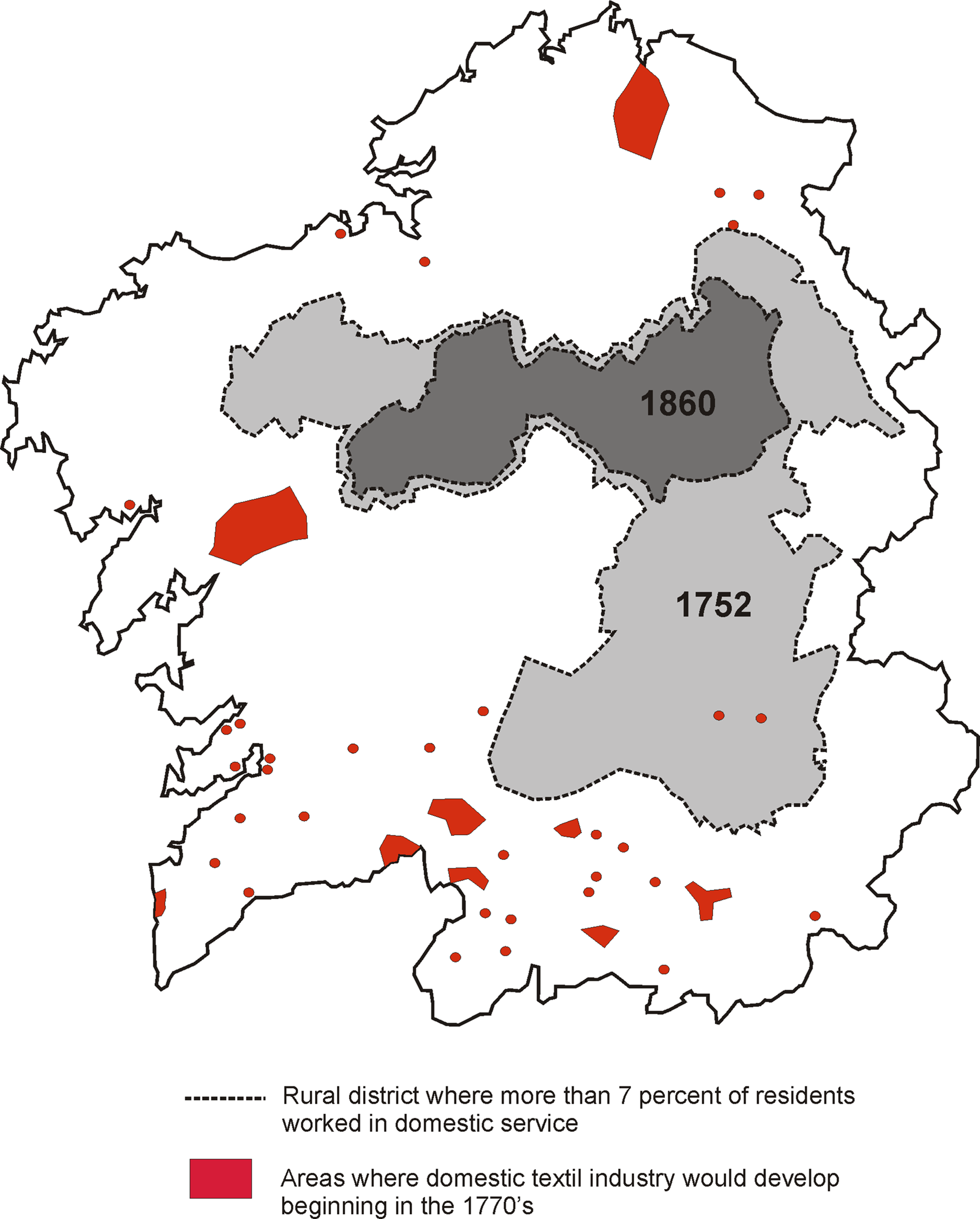

Nevertheless, in the first decades of the nineteenth century, the supply of rural domestic service work experienced a strong contraction, particularly in Lugo (Figure 1). This was due to a chain of circumstances that negatively affected the traditional sources of income of the main employers of servants – small nobility, parish clergy, and elite peasantry. These circumstances included the abolition of feudalism (1811) and peasants’ subsequent resistance to paying feudal rents to lords and the church; falling agricultural prices at the beginning of the nineteenth century and, more generally, the end of the era of agricultural prosperity (1770–1840); loss of income caused by the war against the French (1808–14); disentailment of ecclesiastic assets (1836, 1841); and the implementation of a new fiscal system (1845) (Dubert, Reference Dubert2015: 79–82).

Figure 1. Contraction of rural domestic service labour markets and expansion of rural domestic industry.

Source: (Dubert, Reference Dubert2015: 80; Carmona, Reference Carmona1990: 80). Prepared by the authors.

A similar process took place over the same period in areas where a rural textile industry (linens) had developed and where, curiously, domestic service lacked importance in the labour market. This is what happened in the old province of Ourense and in territories near the Atlantic and Cantabrian coast that were part of other Galician provinces (Figure 1). After the port of A Coruña was opened to colonial trade in 1765, the linen industry in these territories expanded greatly. Most were rural districts that had experienced strong demographic growth in past decades and thus were characterised by high population densities – from sixty to more than one hundred residents per square kilometre – and a noted predominance of small farms. In this context, the intensive nature of linen work, its reduced opportunity cost, and the easy and quick sale of its product both within and outside of Galicia would turn the industry into an activity that allowed women to gain an income they could contribute to their families’ subsistence (Carmona, Reference Carmona1990: 76–81).

But, as with domestic service, the rural domestic industry began to decline after the war against the French in the mid-1810s. Essentially, this was due to the loss of the Spanish colonial market, where a substantial part of Galicia’s linen production had been sold. Another factor was the systematic competition from cotton fabrics that reached the Iberian Peninsula thanks to intense coastal smuggling. Nor should it be forgotten that the linen industry, whose market continued to shrink, was unable to introduce technical advances in the production process that would have improved the quality and reduced the price of its final products, thus making them more competitive with cotton textiles (Alonso Álvarez, Reference Alonso Álvarez2011: 47; Carmona, Reference Carmona1990: 190–9).

The growing difficulties of rural Galician women to find work in domestic service or the linen industry coincided with the gradual formation of a labour market linked to the care and rearing of foundlings. Although it is impossible to know whether the wet nurses contracted by Galician foundling hospitals after 1822 were at some point in their earlier lives servants or workers in rural industry, what is known is that the new labour market was located near – or in – those areas where, until the beginning of the nineteenth century, women could find remunerated work in domestic service or the linen industry (Figures 1 and 3). Now, scarcity of jobs led some of these women to contract out as external wet nurses for the new foundling hospitals. In most cases, as we shall see, they did not become wet nurses because the wages were high (they were not) but rather because the wages constituted income that was complementary with their domestic economies in a geographic area that lacked wage alternatives. We will explore this phenomenon, which has been observed in other places in Europe (Florenty, Reference Florenty1991: 623–5; Fonte, Reference Fonte2005: 391; Cavallo, Reference Cavallo1983: 402), in the following pages.

Information from sources involved in the operation of five of the eight foundling hospitals (that existed in Galicia after the implementation of the benevolence laws) will help us describe the social-labour profile of wet nurses. The same information will also help us locate and describe the institutions’ labour markets, determine their economic impact on the surrounding rural world, and begin to understand the importance of wet nurse wages for family economies.

To address all of these questions, we have used information contained in a varied body of documents composed of annual payment books, receipts for the surrender of children, credentials provided by wet nurses when they received children, and notebooks that followed the upbringing of foundlings, all from the hospitals of Santiago (1860),Footnote 1 A Coruña (1858–60),Footnote 2 Ferrol (1854–93),Footnote 3 Ourense (1858–60),Footnote 4 and Pontevedra (1875–9).Footnote 5 By recording distinct mentions of external wet nurses in these sources (civil status, age, geographic origin, husband’s name, children in care, wages, length of work, etc.) and then cross-referencing them, we have been able to create a nominal dataset that summarises the essential parts of the work histories of 3,743 women from 1854 to 1893.Footnote 6

External wet nurses: profile and labour markets

During the nineteenth century, many of those responsible for foundling hospitals in southern Europe championed the idea that the bulk of wet nurses should be married women of rural origin. They believed that such women combined morality, health, and sturdiness – values that, they hoped, would be transmitted to the foundlings they raised.Footnote 7 Likewise, and especially in the case of Italy, hospital authorities wanted wet nurses to belong to peasant families that were removed from poverty. They asserted that this would be to the benefit of the health and diet of foundlings, who furthermore, in these conditions, would learn useful trades with which they could make a future living (Kertzer, Koball, White, Reference Kertzer, Koball and White1997: 214–15).

However, in practice, the continual arrival of children to the foundling wheel as well as the economic problems suffered by foundling hospitals, forced administrators to accept young women from poor strata of peasantry as wet nurses. This is what happened in the foundling hospitals of northern Portugal. There, the majority of wet nurses belonged to families of day labourers or small peasants whose lands were insufficient to support a family, and so the women’s wages helped with the needs of their domestic economies. Similarly, in Spain (as in Italy), the bulk of these women usually resided in rural areas that were relatively distant from the foundling hospitals and whose agrarian economies were, moreover, very poor and based on self-subsistence. The administrators of French foundling hospitals, however, were always aware that poverty was an intrinsic characteristic of the families of the women that worked as external wet nurses (Fonte, Reference Fonte2005: 384–5; Sarasúa, Reference Sarasúa2021; Mazzoni and Manfredini, Reference Mazzoni and Manfredini2007: 87; Brunet, Reference Brunnet2008: 161–2; Bardet and Faron, Reference Bardet and Faron1996: 144).

The sources used for this research do not allow us to systematically and precisely establish the social origin of the wet nurses employed by Galician foundling hospitals. However, the available evidence indicates that – as in neighbouring Portugal – these women came from families of day labourers or small peasants with little land (whether owned or leased), which forced family members to develop intensive pluri-activity in order to survive. For example, between 1855 and 1859, marriage certificates in the municipality of Saviñao (in Galicia’s interior) show that wet nurses who appeared on the roster of the Royal Hospital of Santiago were married to day labourers. Regarding this point, we have located up to ten cases in San Martiño da Cova, one of the parishes with the greatest number of wet nurses in the municipality during those years.Footnote 8 Similarly, the significant presence of small peasants and day labourers in mountain and ‘high country’ districts that were especially tied to the operation of foundling hospitals in Ourense, Santiago de Compostela, and Pontevedra tells the same story, as we shall see. In these districts, some women specialised in the occupation of wet nurse after the possibility of making a wage from domestic service had disappeared (Figures 2 and 3).

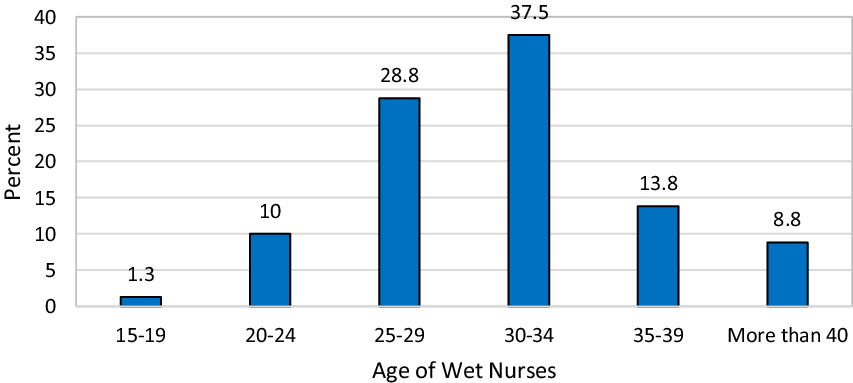

Figure 2. Age distribution of wet nurses of Ferrol’s foundling hospital (1854–93).

Source: ADP, Hogar Infantil de Ferrol, legajos M. 4169, M. 4170 and M. 4171. Prepared by the authors.

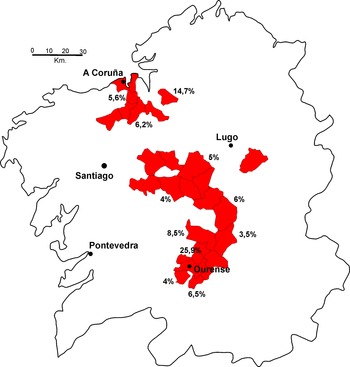

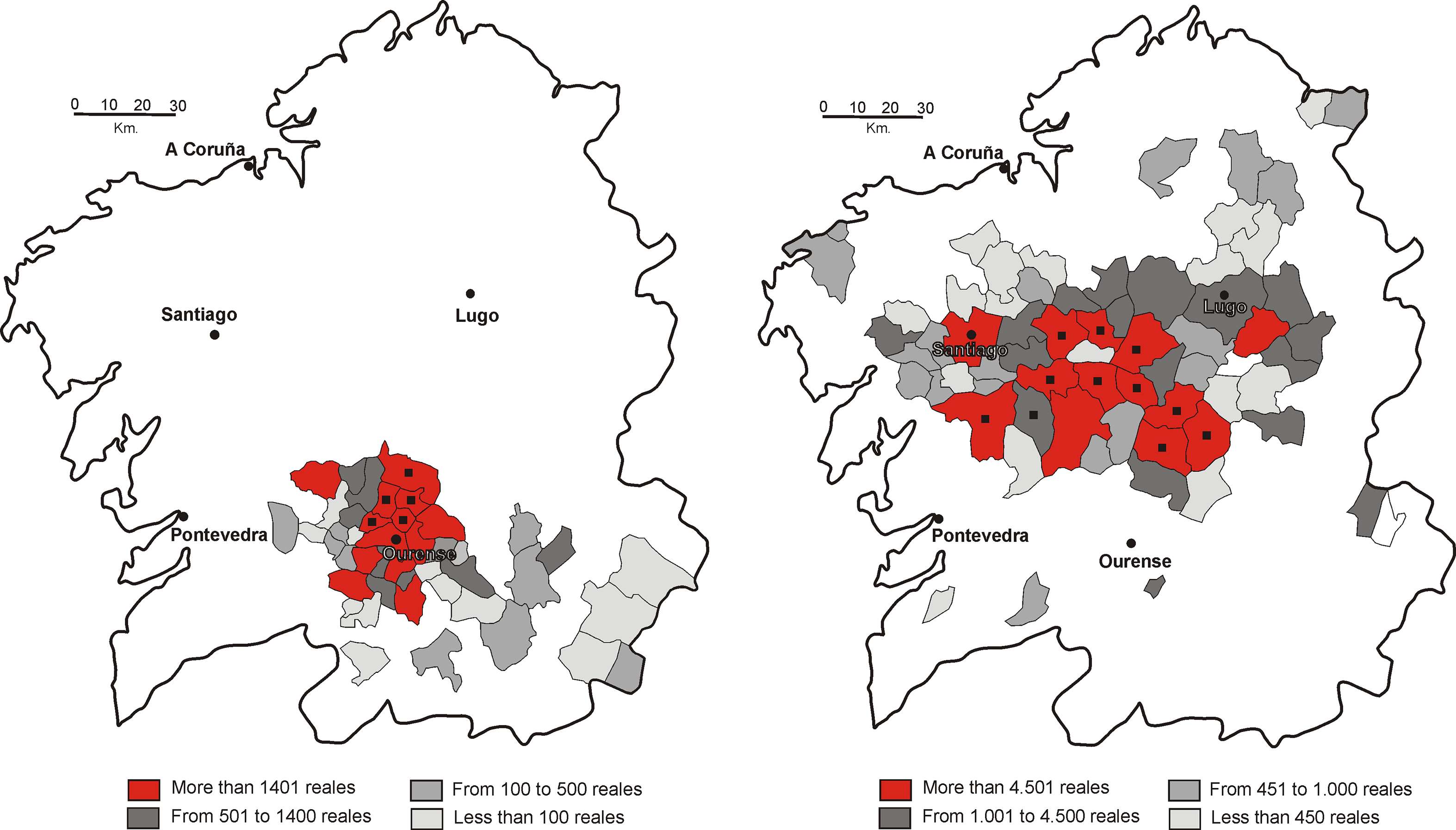

Figure 3. Location of labour markets for external wet nurses of Galician foundling hospitals (1858–60).

Source: AHUS, Sección Expósitos, legajo 233; ADC, Hogar Infantil da Coruña, legajo M. 4127; Archivo Histórico Provincial de Ourense (hereafter AHPO), Fondo Deputación Provincial, Inclusa, legajos 5904, 5905, 6416, 6417. Prepared by the authors.

Assuming this social origin for the majority of our wet nurses, we analysed information contained in several 1860 rural municipal enumerator books from interior Galicia, north-west Galicia, and the foothills of the mountain chain that divides Galicia from north to south (known as the Dorsal Gallega). Our analysis reveals that the households of day labourers were formed by an average of almost four people. That is, they basically consisted of a father, a mother, and two children. In contrast, families identified in the same sources as those of labradores (small farmers belonging to the middle or upper strata of Galicia’s peasantry) were formed by an average of five or six people, of which two were children of the head of household.Footnote 9 This means that the households of the day labourers were on average 40 per cent smaller than the families of the middle and upper sectors of the Galician peasantry, probably due to a combination of late marriage and high infant mortality rates. In any case, this mean household size is similar to that of those Spanish regions which – according to the 1860 census – had a high number of day labourers among their peasantry, such as Extremadura (4) or Andalusia (4.2).

Starting from this base, documentation from the various foundling hospitals allows us to sketch a profile of Galician wet nurses. Their basic features depended on two variables: the size of the institution, and the financial backing granted by authorities for the institution’s operation. We know that these two variables were present throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for the large foundling hospital created at the beginning of the modern era, the Royal Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, where married women were the majority of external wet nurses. Both factors were also present for the foundling hospitals established between 1777 and 1816 – all of which were very small – as long as they received economic support from local authorities and private individuals. Such support let them avoid operating as a mere hijuelas Footnote 10 of the Compostela hospital, which was the case, for example, of the foundling hospital of A Coruña.

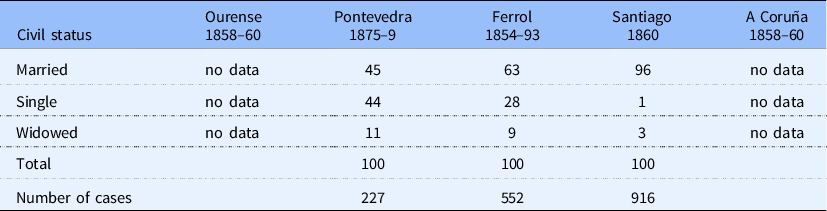

According to this, between 1787 and 1896, 92–8 per cent of the external wet nurses in Santiago were married women of rural origin (see Table 1). For its part, mentions of the systematic appearance of these women as wet nurses in the scant sources preserved for A Coruña’s hospital – which was financed by the church, private donations, royal authorities, and the municipal council – are recorded only three months after its establishment, in July 1793. At the time, its administrators showed a firm desire to keep and care for children until they reached legal age, thus saving the children a trip to Santiago de Compostela, which the administrators considered to be arduous and harmful to their lives. Their idea was to operate autonomously, emulating the model of the Compostela hospital (López Picher, Reference López Picher2017: 603–09, 612).

But the presence of married women working as wet nurses in small foundling hospitals that appeared between 1777 and 1816 (which lacked economic resources and firm institutional support for their operations, whether from the church, the crown, or the municipal councils of the cities in which they were located) was much lower.

This was the case, for example, of Ferrol’s foundling hospital (established in 1786). The same would occur with foundling hospitals that were founded with very few means during the second half of the nineteenth century, such as the one in Pontevedra (established in 1872). Even so, for both cases, the rural provenance of wet nurses, as a whole, remained about 86–7 per cent of the total. In this circumstance, the lesser role of married women could be explained by a combination of welfare constraints and material shortages, which initially led many of the foundling hospitals that opened between 1777 and 1816 to function as dependent branches of Santiago’s hospital, where they periodically sent children that had been abandoned in their own foundling wheels.Footnote 11 This economic and human precariousness, together with the need to attend to the children at the first moments of their lives, must have contributed to the relaxation of the moral conditions required of wet nurses until then, thus allowing a greater number of single women to enter the profession.

From this perspective, it is understandable that 63 per cent of the external wet nurses working for Ferrol’s foundling hospital between 1854 and 1893 were married, 28 per cent were single, and 9 per cent were widowed (see Table 1). This occurred in a welfare context whose responsible parties had continued sending the bulk of its children to Santiago until at least the second half of 1843, due to the lack of material and human means needed to care for them on site (Montero Aróstegui, Reference Montero Aróstegui1857: 544). In line with what has been shown, the presence of single and widowed wet nurses was greater in the hospitals founded later, such as the one in Pontevedra (created in 1872), where married women represented just 45 per cent of the total in 1875–9. This percentage was almost equaled by that of single women, 44 per cent, while widows comprised 11 per cent (see Table 1). This composition would generally continue for the following years (Rodríguez Martín, Reference Rodríguez Martín2003: 183). The percentage of single wet nurses is very similar to that of the small foundling hospitals in the neighbouring regions of northern Portugal, where throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, between 34 and 40 per cent of wet nurses were single (Fonte, Reference Fonte2005: 383–4).

Regardless of the problems and frauds that these single wet nurses may have perpetrated in Pontevedra – or whether the solutions implemented by hospital administrators were the same as those tested in northern Portugal – their importance for the occupation is explained by a combination of factors (aside from the smallness and economic precariousness of the institution) (Rodríguez Martín, Reference Rodríguez Martín2003: 181–3; Fonte, Reference Fonte2005: 369–70, 392). One was the rural textile industry’s gradual loss of relevance as a potential source of income for women in the countryside (Carmona, Reference Carmona1990: 190–9). Another factor was the proletarianisation (experienced by the whole Galician peasantry) that stemmed from the implementation of a new fiscal system in 1845. The new system increased the tax burden on the rural world by more than 200 per cent between 1845 and 1876 (Vallejo Pousada, Reference Vallejo Pousada1994: 263–5). Nor can the terrible effects of the agricultural crisis of 1852–8 be forgotten, which, due to its severity and impact on domestic economies, contemporaries would compare to the Irish crisis of 1845–9 (Rodríguez Galdo and Dopico, Reference Galdo, Xosé and Dopico1981: 26–30).

In this context, men’s migration to America shot up, and in the rural parishes of coastal territories the number of households headed by single women increased, especially among the poorest sectors of the peasantry. These phenomena coincided with the rise in illegitimacy recorded in the region since 1820 (Vázquez González, Reference Vázquez González2015: 21–58; Dubert, Reference Dubert2018: 100–02). What occurred in the rural parish of Santo Tomé de Piñero, located 12 kilometres from the city of Pontevedra, serves as an example. There, in 1883, one of every two households was headed by a day labourer, and two-thirds of these households were led by women. Half of these women were single, and half were widowed. One of three were in charge of small children.Footnote 12 For all of them, working as a wet nurse would mean being able to count on a secure source of income. For Pontevedra’s foundling hospital, as for those in northern Portugal, these women were potential cheap labour, given the low wages that were paid in both regions for the nursing of foundlings in this period (Rodríguez Martín, Reference Rodríguez Martín2003: 181–3; Fonte, Reference Fonte2005: 388–90).

The presence of single women in the occupation likewise had the virtue of changing somewhat the traditional form of recruitment that had prevailed since at least 1822. As in other countries in southern Europe, such as Italy, rural parish priests played an important role (Kertzer, Koball, White, Reference Kertzer, Koball and White1997: 214). These priests exacerbated the vigilance exercised over the labour performance of wet nurses, particularly if they were single.

We know about changes in the form of recruitment thanks to the turnover that many children endured, with some being cared for by two or more wet nurses from Pontevedra’s foundling hospital. Between 1875 and 1879, 18 per cent of its wet nurses took part in such turnovers, that is, one out of six contracted by the institution. This is how we know that for some single women access to the occupation took place apart from the reports and recommendations (noting the good moral and social behaviour of job applicants) that rural priests usually sent to authorities. Instead, such access was gained when, after some time had passed, a wet nurse let administrators of the foundling hospital know that she did not find herself in conditions to care for the assigned child and proposed a sister, sister-in-law, daughter, or close relation as a substitute for the post. In this manner, during the first years of its life, a foundling could be cared for by two or more wet nurses belonging to the same family or within the same family environment. In fact, in the years 1875–9, 57 per cent of the wet nurses who engaged in such turnovers at the Pontevedra foundling hospital were single women, and in two-thirds of these cases, their places were taken by other single women. Something similar occurred with married women – who comprised, during the same years, 37 per cent of the wet nurses who took part in this circulation of children – given that for half of them, their substitutes were young, single women who not infrequently were bound by ties of kinship or affinity. This was how, in the end, the work stayed in the hands of women from the same family circle.

A good example of this is provided by the actions of Manuela Caramés, married to José Picallo and resident of the parish of San Andrés de Souto, part of the municipality of Estrada. In early 1882, the administrators of Pontevedra’s foundling hospital recorded that Manuel José, the foundling that the above-mentioned Manuela had taken care of since 1878, had passed into the hands of her single daughter, Josefa Villar Caramés. Josefa would die at the end of 1892, at which point Manuel José would be returned to the foundling hospital, from which he immediately left for a hospice, since there is no assigned budget entry for his food.Footnote 13

What happened in Pontevedra was not unusual for this type of institution, neither in Galicia nor in Europe (Brunet, Reference Brunnet2008: 158; Fonte, Reference Fonte2005: 371–3; Kertzer, Koball, White, Reference Kertzer, Koball and White1997: 214–15; Shorter, Reference Shorter1977: 185). A sign of this was the 12 per cent of external wet nurses in Ferrol who, between 1843 and 1893, took part in such turnovers, with 58 per cent of them single women and 35 per cent married women. In such circumstances, rural priests redoubled their vigilance over wet nurses in general, and over single women in particular. In 1854, the priest of San Estevo de Sedes, a parish located about 11 kilometres from Ferrol, wrote to officials of the foundling hospital requesting a list of the parish’s wet nurses, since,

According to the instructions communicated to me in recent days, sent by the Governor of the Province and by his Prelate, [it is ordered] that all persons who have in their care foundling children appear before their respective parish priests once each month, but since I do not know how many or who are the women that have them, I need for you to send me a list of those who have foundlings so that I can make them appear.Footnote 14

In the preserved documentation, information about wet nurses’ profile – beyond their civil status and place of origin – is scarce and fragmented. Only sources from Ferrol’s foundling hospital are clearer in this regard, though they provide us with a rather stereotyped image of the women, referring to their physical appearance – qualitative assessment of their height; colour of hair, eyes, and skin; form of nose and face – and their age at the moment they took charge of children (Figure 2). Regarding age, we know that external wet nurses who worked for the institution between 1854 and 1893 were, on average, thirty-eight years old. The single women – 28 per cent of the total, we must remember – had, in contrast, an average age of twenty-nine; that is, three years older than the average age at which young Galician women got married in 1887. This possibly means that they had been mothers after broken marriage promises from suitors, a circumstance that, since the beginning of the nineteenth century, was behind many rural Galician women’s entry into the world of illegitimacy (Dubert, 2013: 107–15). For their part, married women were, on average, thirty-three years old, and widows were forty-one years old, indicating in the latter case that these women worked mostly in the care of children already weaned, so their wages were always lower than those of the other women. With the exception of widows, the ages for Ferrol’s wet nurses are on the fringes of what Italian experts of the era considered suitable for performing the occupation (Kertzer, Koball, White, Reference Kertzer, Koball and White1997: 214).

The evidence about the ages of the 552 external wet nurses employed by the foundling hospital of Ferrol between 1854 and 1893 is enormously valuable. For instance, it allows us to see that 90 per cent of the women working for this institution were between twenty and forty years old (Figure 2). Assuming that the same was true in other Galician foundling hospitals, we can compare the number of external wet nurses in each municipality who were linked to the foundling hospitals of Santiago (1860), A Coruña (1858–60), and Ourense (1858–9) with the total number of women twenty to forty years of age recorded in those municipalities in the 1860 census. This will allow us to establish the approximate percentage of women who would have specialised in the profession at the local level. Mapping the municipalities in which more than 3 per cent of the women twenty to forty years old were wet nurses allows us to bring their labour market to light.Footnote 15 We show that the rural districts where a more or less significant group of women were linked to this occupation gave rise to a sort of north-south continuum situated along the length of the foothills of the Dorsal Gallega (Figure 3).

The location of the main labour markets for wet nurses in mountainous areas was a phenomenon common to foundling hospitals in the countries of southern Europe (such as Italy, France, and Spain) in the nineteenth century. Most of these areas were situated in places far from the institution, normally at an average distance of 60 to 100 kilometres, and were characterised by a harsh climate, low-yield agriculture performed by small peasants within systems of self-sufficiency, and men’s seasonal emigration. Hospital administrators’ choice of such areas is explained by the cheapness of the workforce. Families in these geographic areas needed to be able to count on some secure monetary income, especially during the dead of winter, when the land was not worked. Not infrequently, the work of the wet nurse was prolonged for years thanks to the successive breastfeeding of one or more children, and, depending on the case, the care of weaned children until they reached six or seven years of age. This was how they were able to pay rent and taxes, and take care of their families’ contingencies and daily expenses (Brunet, Reference Brunnet2008: 162–4; Florenty, Reference Florenty1991: 623–5; Mazzoni and Manfredini, Reference Mazzoni and Manfredini2007: 84; Kertzer, Reference Kertzer1991: 20; Cavallo, Reference Cavallo1983: 402–03; Sarasúa, Reference Sarasúa2021: 111–12, 197–200, 216–19, 295–6; Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo2021: 53–5).

Two points in this geographic continuum stand out for their high concentrations of wet nurses (Figure 3). The first is composed of municipalities southeast of the city of A Coruña. A case in point was Irixoa, situated in the foothills of Sierra da Loba, where in 1860 almost 15 per cent of the women between the ages of twenty and forty worked for A Coruña’s foundling hospital. The second point – more important because of the confluence of recruitment carried out by the foundling hospitals of Santiago, Ourense, and, after 1872, Pontevedra – was located in the rural districts of the foothills of Sierra do Faro, north-east of Ourense, and the western foothills of Sierra de Queixa, south-east of the same city. As an example, what occurred in the small municipalities of Carballedo and A Peroxa, both at the foot of Sierra do Faro, can be cited. In 1860, 18.5 per cent of the municipalities’ women who were twenty to forty years old were employed as wet nurses by Ourense’s foundling hospital. Both were municipalities where, until the start of the nineteenth century, it was not difficult for women to work in domestic service, given the relative abundance of large houses owned by nobility, small nobility, and parish clergy (García Iglesias, Reference Iglesias and Manuel1992, vol. 1: 214, 231; Figure 1).

Everything thus indicates that it was in the highlands where a clear specialisation in the occupation by women from the lowest strata of peasantry occurred. Even so, it should be kept in mind that in Galicia the spatial definition of this labour market was the fruit of two different recruitment strategies that were put into practice by different benevolence institutions of the region. On the one hand, there was that of Santiago’s foundling hospital, which since the beginning of the nineteenth century tended to search for wet nurses in the rural districts of the foothills of Sierra do Faro, a recruitment strategy that after 1872 would be imitated by Pontevedra’s foundling hospital. At the end of eighteenth century, these rural districts were the traditional route used by those who transported foundlings from the rural areas of the south of the current province of Lugo to the Santiago’s foundling hospital (Dubert, 2013: 155). At that moment, local parish priests began to recommend women from that rural districts as wet nurses, first to the administrators of the Royal Hospital of Santiago and, later, to those of the Pontevedra’s foundling hospital. Thus, for example, since 1873 the systematic participation of some Pantón priests is documented in the selection of wet nurses outside the municipality, women who ended up working for the aforementioned Pontevedra’s foundling hospital (Rodríguez Martín, Reference Rodríguez Martín2003: 193–4).

On the other hand, there was the strategy practiced by the foundling hospitals of A Coruña and Ourense, whose operations gave rise to a welfare hinterland that extended across the municipalities of their more or less nearby environs, thus conditioning the idea that the main ‘nurseries’ for external wet nurses have, as a rule, been located in places distant from the city, as happened in Santiago, Pontevedra, and most peninsular and European foundling hospitals (Figure 3).

The economic impact of foundling hospitals: wages and the family economies of wet nurses

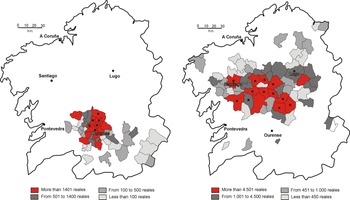

The demand for external wet nurses in the foundling hospitals of rural districts in the foothills of Sierra do Faro leads us to ask about the economic impact that their operation must have had on the districts. To address this question, we have reconstructed the capital injected by the two principal foundling hospitals of Galicia (those of Ourense and Santiago) into the places of origin of the wet nurses who worked for them.

The balance sheet of income and expenses for the Ourense foundling hospital’s fiscal year 1864–5 reveals that it had a budget of 184,514 reales (hereafter no italics), of which 68 per cent (125,728 reales) went to the payment of wet nurse wages.Footnote 16 This figure is not far from that obtained by reconstructing the amounts delivered to each wet nurse each quarter during the triennium 1858–60: 107,000 reales on average per year.Footnote 17 Assuming that the foundling hospital’s budget was about 180,000 reales per year, then 60 per cent of the budget would have been spent on the cost of external wet nurses. Therefore, during the decade of 1851–60, Ourense’s foundling hospital would have put 1,070,000 reales into the family economies of wet nurses; and in 1861–70 the figure would have been 1,250,000 reales. These amounts, translated into domestic income, would have helped these households, most of which belonged to the lowest strata of peasantry, mitigate the effects of the agricultural-livestock crisis of 1852–8.

This money generally reached the rural districts that formed the foundling hospital’s welfare hinterland, but in particular it went to those in the aforementioned foothills of Sierra do Faro, located to the north of Ourense. Here, according to the 1860 census, 46 per cent of the men who were active in the agrarian sector – composed of proprietors, renters, and day labourers – are classified under the heading ‘field day labourers’ (Figure 4). In these districts, especially in those located in the present-day municipalities (and neighbouring municipalities) of Coles, Carballedo, Vilamarín, A Peroxa, and Amoeiro (shown in Figure 4 with a square), a true labour market for wet nurses existed and functioned. This is indicated by the fact that the 68 per cent of the budget that the foundling hospital spent on wages during the triennium 1858–60 – and, according to the data, also during the decade of 1861–70 – would end up in the hands of women in this region. Here is unambiguous evidence that at this point some of the women had specialised in the profession; concretely, 18 per cent of the total – that is, one in six – of those in age range of twenty to forty years. Moreover, if we include in this limited territorial nucleus the wet nurses who lived in the municipalities of Nogueira de Ramuín and Pereiro de Aguiar, situated in the foothills of Sierra da Queixa, to the east and north-east of the city, we would then see that 76 per cent of the capital earmarked for wet nurse wages was concentrated in only seven of the forty-three municipalities that formed part of Ourense’s welfare hinterlands.

Figure 4. Annual cash transfers from the foundling hospitals of Ourense (1858–60) and Santiago de Compostela (1860) to the rural world.

Source: AHUS, Sección Expósitos, legajo 233; AHPO, Fondo Deputación Provincial, Inclusa, legajos 5904, 5905, 6416, 6417. Prepared by the authors.

At this level, the conduct of the foundling hospital at the Royal Hospital of Santiago, which we must remember was the largest and oldest welfare institution in Galicia for foundlings, was very similar to that of Ourense’s foundling hospital. Its ability to search for wet nurses for the children in its care extended over a wide territory. At its core, the territory included the rural districts on both sides of the foothills of the Dorsal Gallega, as well as the districts of the plateau north of the centre of today’s province of Lugo, the so-called Terra Cha (Figure 4). The first group of districts ran southward along the length of the mountain chain, until just reaching the municipalities of Dozón, Rodeiro, and Carballedo, which acted as a frontier border with the municipalities that formed part of the welfare hinterland generated by Ourense’s foundling hospital.

Across this vast geographic area, Compostela’s institution injected – according to data from the sum of individual wages that its administrators paid quarterly to external wet nurses in 1860 – 205,440 reales.Footnote 18 This means that over the decade of the 1860s the foundling hospital would have transferred to the rural world a minimum of 2,054,000 reales, almost double the amount disbursed by Ourense’s foundling hospital during the same period, although over a significantly much larger territory (Figure 4). The extent of this territory is related not only to the economic power of the institution that housed Compostela’s foundling hospital, the Royal Hospital of Santiago (in 1845 it would become the Central Hospital of Galicia, financed by the four Galician Provincial Councils; García Guerra, Reference García Guerra2001: 224, 288), but also to its recruitment strategy for wet nurses, inherited from the old regime.

Otherwise, the relationship between the foundling hospital in Santiago, as issuer of cash, and the surrounding rural districts, as recipients of the cash, was similar to that found in Ourense. Seventy-one per cent of the capital used by administrators to pay wet nurses tended to be concentrated in a limited number of municipalities – twelve of the total sixty-nine – situated in the foothills of the Dorsal Gallega and in the highlands leading to them (shown in Figure 4 with a square). However, and in contrast to what happened in Ourense, the number of women between the ages of twenty and forty who worked as wet nurses in this small territorial nucleus was limited to just 2.5 per cent of the total. In other words, the operation of Santiago’s foundling hospital did not give rise to, or encourage, the specialisation of women in this profession, even though in municipalities such as Vila de Cruces their numbers made up about 6 per cent of the total, or in Palas de Rei, O Saviñao, and Antas de Ulla, where they were about 4 per cent of the total. Consequently, the income that wet nurses’ family economies obtained by this means would only have helped a tiny part of the region’s peasantry mitigate the negative effects of the agricultural-livestock crisis of 1852–8.

Nonetheless, whether in Santiago, Ourense, or any of the other cities with a foundling hospital, the money that these institutions regularly injected into more or less nearby rural districts always ended up in the hands of wet nurses in the form of low wages, the lowest of Spain. To give us an idea how low, we can take as a reference point what was paid to the external wet nurses of Santiago during the 1850s and 1860s: twenty reales per month (Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo2021: 55–62). This amount was 33–50 per cent lower than the wages offered during the same period in Navarra, Euskadi, Aragón, and Andalucía; 20–50 per cent lower than the wages paid in Castile; 17–33 per cent lower than those delivered in Valencia; and 50–60 per cent lower than those disbursed in the foundling hospitals of big cities like Barcelona, Madrid, and Seville (Sarasúa, Reference Sarasúa2021: 470–82).

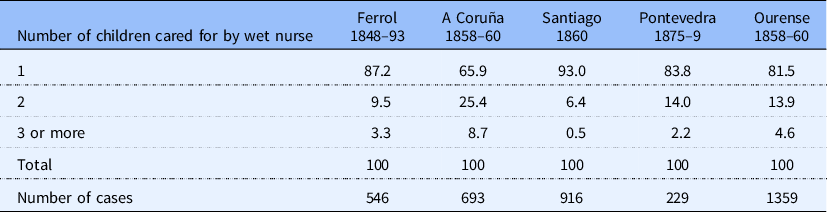

In spite of this, Galician wet nurses could count on various resources to compensate for the lowness of their wages. One of these was domestic production, which saved more than a few expenditures in families’ basket of purchases (Borderías Modejar and Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Borderías Modejar and Muñoz-Abeledo2018). Another, and perhaps more important in this field, was combining the care of a nursing child with that of one or two children who were already weaned (see Table 2). At different points of the second half of the nineteenth century, this ‘dry nursing’ was carried out by approximately 13–19 per cent of the women employed by Galician foundling hospitals, although, in the case of A Coruña’s foundling hospital, the average was about 34 per cent for the years 1858–60.

Table 1. Civil status of wet nurses who worked in Galician foundling hospitals (%)

Source: Arquivo da Deputación de Pontevedra (hereafter ADP), Inclusa provincial, Registro general de entrada de expósitos, legajos 14.721-3 and 14.722-1; Arquivo da Deputación da Coruña (hereafter ADC), Hogar Infantil de Ferrol, legajos M. 4169; M. 4170; M. 4171; Arquivo Histórico da Universidade de Santiago (hereafter AHUS), Sección Expósitos, legajo 233. Prepared by the authors.

Table 2. Number of children cared for by external wet nurses (%) (1858–93)

Source: ADP, Inclusa provincial, Registro general de entrada de expósitos, legajos 14.721-3 and 14.722-1; ADC, Hogar Infantil de Ferrol, legajos M. 4169; M. 4170; M. 4171; AHUS, Sección Expósitos, legajo 233; AHPO, Fondo Deputación Provincial, Inclusa, legajos 5904, 5905, 6416, 6417; ADC, Hogar Infantil da Coruña, legajo M. 4127. Prepared by the authors.

These were women like Gregoria Crespo, a resident of the parish of San Cibrao de Armental, in the Ourense municipality of A Peroxa, who, during the years 1858, 1859, and 1860 cared for two children older than three, Lázaro and Ubaldo, receiving a total of 691 reales for her work, that is, an average of 230 reales per year, or 19 reales per month.Footnote 19 Or there was María Caínzos, a resident of Santa María de Bermes, in the Coruña municipality of Irixoa, who in 1858 and 1859 nursed two foundlings at the same time, which earned her a total of 576 reales per year, or 48 reales per month for both children.Footnote 20 In contrast to what happened in the majority of Galician foundling hospitals, the relatively high wages – within the Galician context – paid by the foundling hospital of Santiago de Compostela (which were as much as 25 per cent higher than those offered in Ourense) together with administrators’ continual vigilance of wet nurses, limited recourse to this practice (see Table 2).

The reconstruction of a family budget for households headed by male day labourers will give us a much better picture of the possibilities that wet nurses’ incomes offered to domestic economies, which will illustrate what happened at this level in the poor strata of peasantry. These households were much more common in Galicia than generally believed. In 1860 the percentage of male day labourers with respect to the total number of men who were active in the agricultural sector – composed of proprietors, renters, and day labourers – was, at 65 per cent in the province of A Coruña and 57 per cent in the province of Pontevedra, greater than the Spanish average. Given their numerical importance in the population of Galicia’s active agricultural men, it is worthwhile to reconstruct their families’ main incomes and expenses to evaluate what the wage contribution of external wet nurses would mean within this framework.

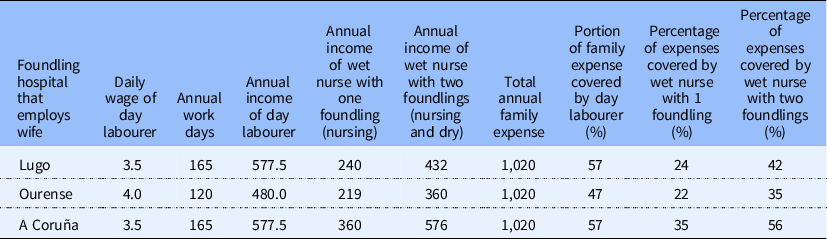

We will consider a typical family composed of two adults and two small children. The head of the house declared himself a day labourer, and the wife worked for one of Galicia’s foundling hospitals. We will pay attention to what happened to this typical family in the middle of the nineteenth century in the Lugo municipalities of the Dorsal Gallega, where women worked as wet nurses for the foundling hospital of the Royal Hospital, and in the rural districts close to the cities of A Coruña and Ourense, where women worked for those foundling hospitals. In these three cases, we will assume, furthermore, that the wives of these typical families would have had two foundlings in their care, a nursing child and a child who was already weaned, for which she earned a lower wage.

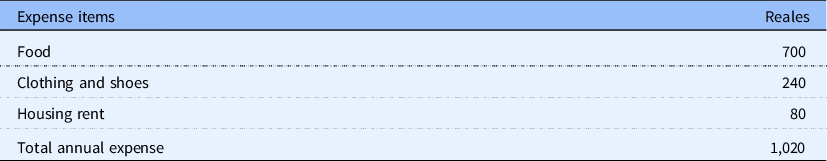

The annual current expenditures of families of agricultural day labourers that we have considered were obtained from the answers to questions four and five of the questionnaire in the Agrarian Survey of 1849–52, sent from the Ministry of Agriculture to local agricultural boards and economic societies on 15th December 1849.Footnote 21 Unfortunately, this documentary source only gives us the expenditure budget of one family of day labourers in the province of A Coruña (see Table 3).Footnote 22 We will start with the assumption that, in its main components (food, housing rent, clothing and shoes), this would have been the average expenditure for families of Galician day labourers in the middle of the nineteenth century. We point out that this budget does not include medical expenses, debt, taxes, or small leisure expenses (for men, the tavern); nor does it take into account the costs associated with domestic production, which certainly had to be important, since day labourers in the countryside had access to small pieces of land, owned or rented, from which were obtained basic foods such as potatoes, cereals (corn and rye), vegetables, and legumes.

Table 3. Annual family expense among male day labourers, A Coruña, 1850

Source: Archivo del Ministerio de Agricultura (hereafter AMA), Encuesta Agraria de 1849–52 (Agrarian Survey of 1849–52), legajo 123. Prepared by the authors.

Taking this into account, Table 3 shows the annual expenses that a day labourer family in Galicia would have had: 1,020 reales. To meet these expenses, the family would count on, to begin with, the daily wage received by the head of the household who worked as agrarian day laborer a total of 165 days per year, as recorded in the Agrarian Survey, if the individual belonged to the provinces of Lugo or A Coruña, or fewer days, about 120, if he was from Ourense.

The daily wage was 3–4 reales. There is daily work for 1/4 of the year. In planting, harvesting, and conservation of plants. Children under 12 years of age go with the cattle and from this age they are put to work farming with tools appropriate to their age. Because the property is highly subdivided, few agricultural day laborers are not owners and own a small piece of land. Although it is very tiny, they try to cultivate it with all care, making them produce as much as it is capable of giving.Footnote 23

Looking at this construction of a budget of income and expenses, it turns out that a husband’s day wage covered 47–57 per cent of family expenses in the middle of the nineteenth century (Table 4). In the case of a wife with a nursing foundling in her care, families in A Coruña and Lugo would be better off. (The hospital of A Coruña paid the highest wages in the region.) In Coruña, the annual domestic budget deficit would be 8 per cent, while in Lugo it would be 19 per cent. These shortfalls would have to be covered through pluri-activity; for example, men’s work in Castile’s harvests, Andalucía’s mines, or the transport and sales of various products in local markets. The earnings of the wife, who worked as a wet nurse with two foundlings in her charge, covered 42 per cent of total expenses in Lugo; a little less in the case of Ourense (35 per cent) and a bit more than half if the wife was employed by the foundling hospital of A Coruña (56 per cent), which traditionally paid higher wages than that of Santiago (Dubert y Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo2021: 55–62).

Table 4. Income and expenses of a family composed of an agricultural day labourer, a wet nurse, two children, and one or two foundlings in 1850 (reales per year)

Source: Libro de Tarjas (wage payments) of Hospital Real de Santiago de Compostela, Payment Books of foundling hospitals in Ourense and Coruña, and AMA, Encuesta Agraria de 1849–52, legajo 123. Prepared by the authors.

Everything shows that the domestic economies of the families studied within each territorial range were practically in budgetary equilibrium, with those of day labourers in A Coruña even showing a tiny capacity for saving. This means that the occupation of wet nurse played an important role in the heart of the limited, fragile family economies of Galicia’s lowest strata of peasantry, since their income, however meagre, was at times greater than that of an agricultural day labourer, who generally worked from a third to half of the year. In this regard, the reconstruction of work histories of some of the wet nurses who resided in the Lugo municipality of O Saviñao reveals that many of them, besides having more than one foundling in their care, were employed a good part of their reproductive lives – between twelve and fifteen years – by the foundling hospital of Santiago, so the income they earned was, as well as continual and regular, an essential component for the survival of their households.

Single women with children and widows must also be considered. Both can be found in Galicia in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, mainly working for the foundling hospital of Pontevedra (Table 1). The single women in Pontevedra’s rural surroundings who had their own children found employment in this foundling hospital. We note that between 1861 and 1870 the rate of illegitimate children in the region was 12 per cent, while in the whole of Spain it was 5.5 per cent (Dubert, Reference Dubert2018: 100; Lopez Taboada, Reference Taboada and Antonio1996: 154–5). Widows specialised in raising children who were already weaned, that is, between eighteen months and seven years of age, while single women took charge of recently born foundlings, who they raised with their own children. In both cases, wages they received from the foundling hospital – together with wages earned from their work as agricultural day labourers, weavers, spinners, dressmakers, and from activities such as herding and gardening, tasks which foundling children could help with from a young age – would allow them to survive (Rodríguez Martín, Reference Rodríguez Martín2003; Dubert, Reference Dubert2018: 104–5). Although there are no specific studies on the survival of these women, we do know from our sources that with the foundling hospital’s wages, they were able to rent worker’s housing and purchase a kilogram of bread and another kilogram of potatoes (Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Dubert and Muñoz-Abeledo2021). They thus had a secure source of calories; even more so if we take into account that most houses had vegetable gardens, whose cultivation allowed for domestic production, a formula that characterised peasant economies of the region until practically the end of the twentieth century.

On the other hand, the wage charged by external wet nurses of the foundling hospitals in Santiago, Pontevedra, and Orense hardly varied throughout the last third of the nineteenth century and was, furthermore, the same for Santiago and Ourense after 1885: thirty reales per month for breastfeeding. We know from reports by the Commission of Social Reforms in the 1880s that this wage was similar to the wages received by women working in weaving mills of A Coruña and by women sardine packers in the salting plants of the seaboard (Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Muñoz-Abeledo2010). For their part, wet nurses married to day labourers in Galicia’s interior made a similar contribution to their family economies as that made by women in salting who were married to fishermen in coastal Galicia – covering between 20 and 30 per cent of the family budget.

Conclusion

The expansion of Galicia’s assistance system in the years 1777–1816 laid the foundation for what would become, after 1822, a regulated and structured labour market for wet nurses. This expansion coincided with a period in which it became increasingly difficult for women to find work in domestic service or the rural textile industry (Muñoz-Abeledo, Taboada and Verdugo Reference Muñoz-Abeledo, Taboada and Verdugo2015; Dubert, Reference Dubert2006). This encouraged the gradual development of the occupation of wet nursing for women in rural districts, until, by the middle of the nineteenth century, it had become a specialised job and, as such, was recorded in the official bulletins of the different Galician provinces.Footnote 24

For the care they offered children, wet nurses received a monthly wage that was delivered in several payments during the year. In this sense, they formed part of quasi-fixed labour force during an important part of their life cycles. The wage was low, especially if we compare it with what was paid by foundling hospitals in other regions of the Iberian Peninsula (Catalonia, Navarre, Euskadi, etc.). Even so, it has been shown to be key for the successful operation of family economies, independently of whether or not the wet nurses who received it worked in a geographic area that specialised in the occupation. Nursing or caring for a single foundling provided limited income, but women who cared for two or more foundlings earned significantly more. Provided that they were married to day labourers, as was likely, these women (with more than one foundling) could make a wage contribution that would cover between 35 and 56 per cent of total family expenses (see Table 4). These percentages are greater than those known for other places in northern Spain for the same period (Le Play, Reference Le Play1990).

Another source of income cannot be forgotten – what the families of wet nurses received by hiring out their foundlings for fieldwork. Many foundlings remained in the rural districts where external wet nurses had raised them. Upon reaching the age of six, they were adopted by their wet nurses. Thus, for example, in 10 per cent of the households in the 1900 municipal enumerator book for O Saviñao, whose wet nurses mostly worked for the foundling hospital of Santiago, it is possible to find individuals with the name or surname ‘Foundling’, who are recorded as heads of household or as family members.Footnote 25 This evidence would warrant greater research to deepen and widen what is known about child labour in rural Galicia (Muñoz-Abeledo, Reference Muñoz-Abeledo2017).

Acknowledgements

This research has been financed by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain to the project: ‘The Transformation of Occupational Structure, Spain 1860–1970: New Evidences for Non Agrarian Occupations Revising Population Censuses’ (PID2021-123863NB-C22), and by Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Universidades – Xunta de Galicia (ED431B 2021/06, GPC-GI 1921). The authors would to thank also the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.