In the first three papers of this series (Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams & Garland, 2002a , Reference Williams and Garland b ; Reference Wright, Williams and GarlandWright et al, 2002), we looked at the different areas of human experience that alter during times of mental illness. The Five Areas Assessment model (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001; see Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams & Garland, 2002a , Fig. 1) provides a clear summary of the range of problems and difficulties faced by individuals in each of the following domains:

-

1 life situation, relationships, practical problems

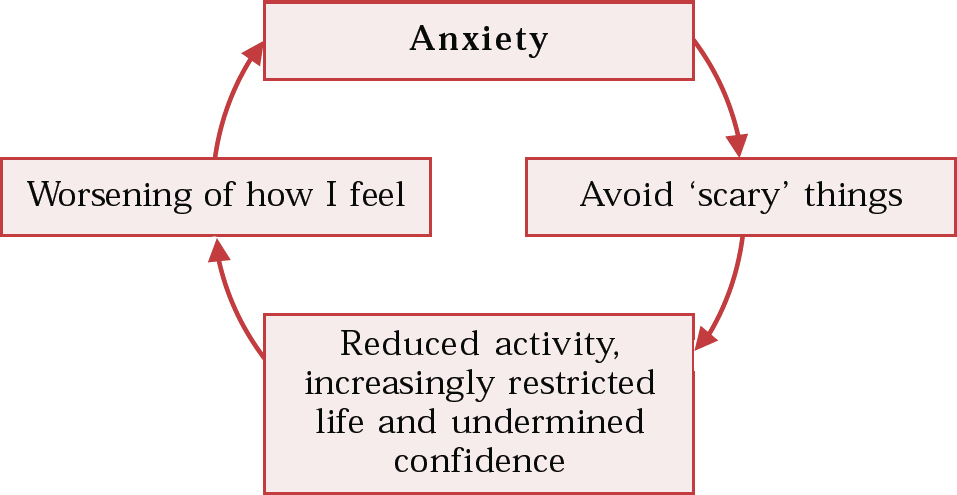

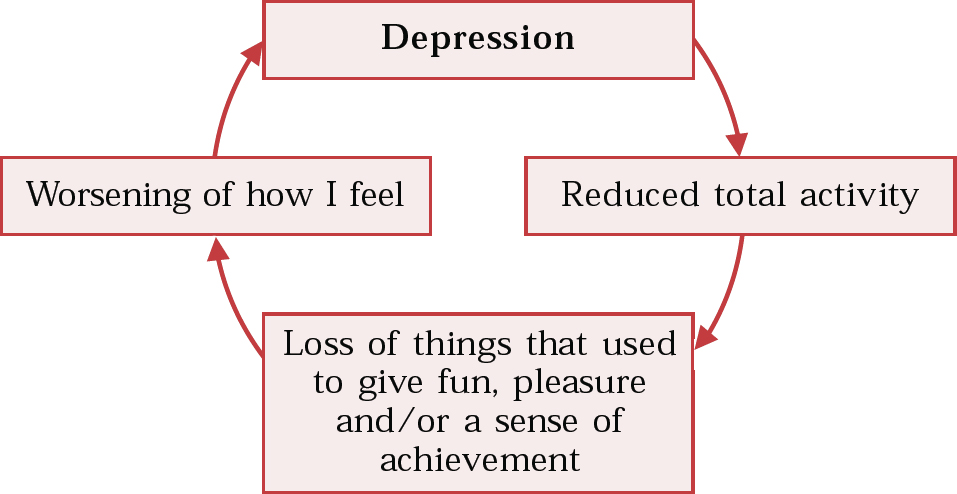

Fig. 1 The vicious circle of reduced activity (after Reference WilliamsWilliams 2001a)

-

2 altered thinking

-

3 altered emotions (moods or feelings)

-

4 altered physical feelings/symptoms

-

5 altered behaviour or activity levels.

These five interdependent domains show that what individuals think about a situation may affect how they feel emotionally and physically, and also alter what they do. The model provides a useful structure to help identify clear clinical targets for change. Intervening in any one of the areas can lead to benefits in all. The focus of the current article is the area of altered behaviour or activity levels. Using depression and anxiety as an example, we examine how changes in this area can maintain or worsen these disorders. These interventions may be offered alongside other approaches such as medication.

The model identifies three main ways that altered behaviour can worsen mood – each of these acts as a ‘vicious circle‘ that maintains or worsens how the person feels.

The vicious circle of reduced activity

When people feel depressed, the presence of the biological symptoms of depression (altered physical feelings), coupled with negative thoughts and perceptions (extreme and unhelpful thinking) and the attendant emotional state in which little is enjoyed (altered emotional feelings), results in a restriction of the activities that they feel able to engage in (reduced activity). Consequently, they reduce their total activity levels and may also stop doing things that previously gave a sense of pleasure and/or achievement. Typically in depression, in the face of problematic symptoms that interfere with day-to-day functioning, depressed individuals decide to invest their now severely limited energy into essential activities only. Usually this means going to work, looking after the children and so on. Hobbies, relaxation time and social activities are often given less priority. This has two consequences. First, the opportunity for engaging in pleasurable activities is reduced. Most of us can recognise that if our only activities were functions of our responsibilities as employees, parents and partners, to the exclusion of hobbies and social activities, then we would quickly become demoralised. This happens in depression, and individuals with depression derive little or no sense of pleasure or achievement from activities (Reference CostelloCostello, 1972). The consequence of stopping doing things that would normally be pleasurable or lead to a sense of achievement is a worsening of the feelings of depression (Reference LewinsohnLewinsohn, 1975). Second, in withdrawing from social activities individuals may be reducing their access to valuable sources of support and encouragement in tackling their current illness. These reactions result in a vicious circle of reduced activity (Fig. 1).

Once this vicious circle is established, the individual becomes trapped in a cycle of inactivity. Tasks become harder to complete, and ultimately activities that, before the onset of depression, were seen as routine and easy (such as getting washed and dressed, cooking a meal, watching a television programme, visiting shops or travelling on public transport) can seem insurmountable. The vicious circle can be overcome by creating a step-by-step plan to reintroduce those things into life that previously gave a sense of pleasure or achievement. The term ‘step-by-step plan‘ has been developed as part of the Five Areas training materials and is used instead of the traditional cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) terminology of ‘activity scheduling‘ (Reference Lewinsohn and GrafLewinsohn & Graf, 1973).

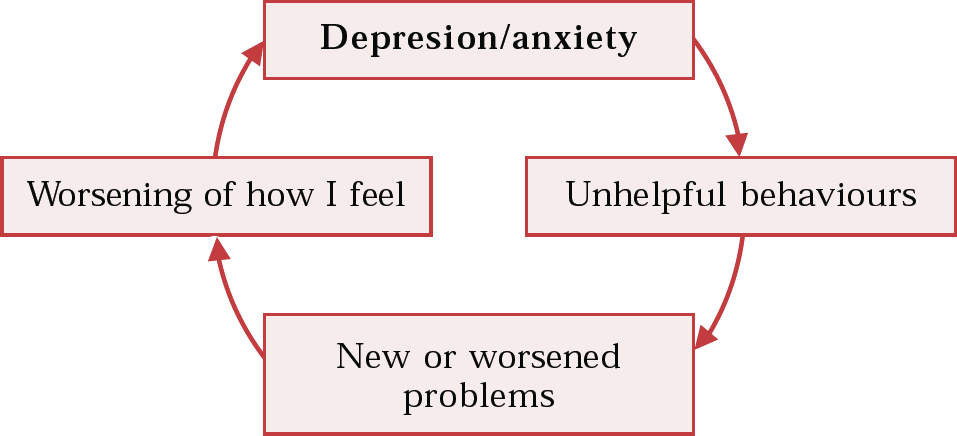

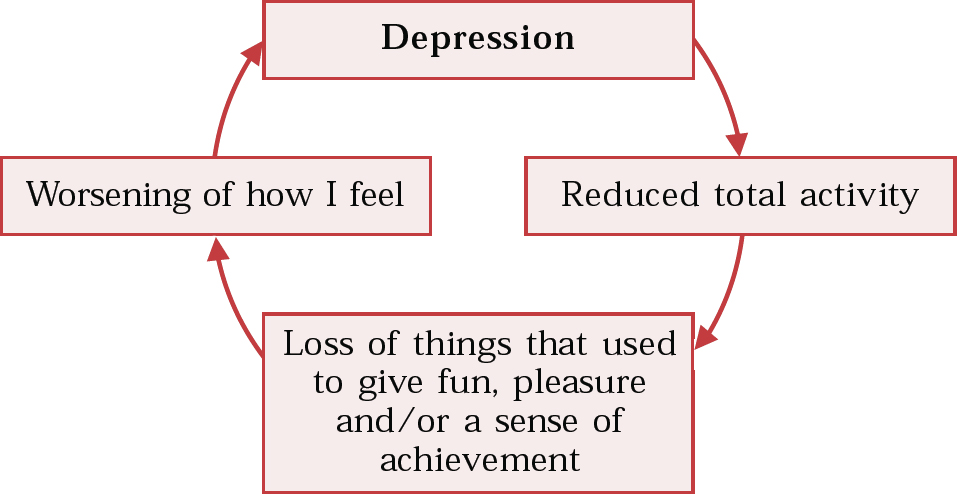

The vicious circle of avoidance

When people become anxious, they start to avoid places and situations where they predict that anxiety will occur. This avoidance adds to their problems because, although they may feel less anxious in the short term, in the longer term this behaviour maintains and worsens their problem (Reference Matthews, Gelder and JohnstonMatthews et al, 1981). The avoidance exacerbates anxiety, further undermines confidence in their ability to do things and results in an increasingly restricted lifestyle ruled by fears. Avoidance also teaches an individual the unhelpful rule that the only way of dealing with a difficult situation is to avoid it. In addition, avoidance prevents the anxious individual from discovering whether or not fears are based on accurate predictions or are in some way extreme and unhelpful.

Once the above pattern is established then a ‘vicious circle of avoidance‘ may result (Fig. 2; Reference Williams, Richards and WhittonWilliams et al, 2002). The vicious circle leads to a downward spiral of emotions, as each time it is completed individuals feel worse about themselves and their circumstances. Again, the vicious circle can be overcome by creating a step-by-step plan to test out and challenge the ‘catastrophic‘ fears that often drive the avoidance and to face up to feared situations. The traditional CBT terminology for such a plan is ‘progressive exposure‘ (Reference MarksMarks, 1987).

Fig. 2 The vicious circle of avoidance (after Reference Williams, Richards and WhittonWilliams et al, 2002b)

The vicious circle of unhelpful behaviour

People experiencing anxiety or depression usually alter their behaviour to try to manage or overcome their problems. This altered behaviour may be either helpful or unhelpful.

Helpful activities include:

-

• reading or using self-help materials to find out more about the causes and treatment of anxiety or depression (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001b );

-

• going to see a doctor or health care practitioner to discuss what treatments might be helpful;

-

• maintaining activities that provide pleasure or support such as meeting friends, doing hobbies, playing sport or going for a walk;

-

• taking a realistic approach to overcoming problems and anticipating that the process will take time;

-

• allowing time for change and not abandoning a solution if immediate results are not seen. This means giving any solution a fair trial: most fair trials should be viewed in terms of weeks and months not minutes, hours or days. (It is timely to remind ourselves as clinicans that the same applies to us when trying to learn a new skill such as cognitive therapy.)

Unhelpful behaviour is unfortunately common. For example, people may try to block their emotions by:

-

• misusing alcohol or drugs to manage negative mood states or unpleasant thoughts;

-

• engaging in acts of self-harm (by cutting or scratching themselves) as a way of numbing painful emotions;

-

• actively withdrawing from others and isolating themselves from family and friends because of uncharacteristic feelings of excessive irritability (Reference FersterFerster, 1973); this might involve more subtle changes in behaviour such as avoiding eye contact and abruptly ending conversations (Reference Youngren and LewinsohnYoungren & Lewinsohn, 1980);

-

• trying to spend their way out of depression or anxiety by buying new clothes and goods in order to cheer themselves up (‘retail therapy‘);

-

• becoming promiscuous.

In anxiety, individuals develop specific unhelpful behaviours to try to prevent the feared catastrophe occurring. !Reference SalkovskisSalkovskis (1991) calls such strategies ‘safety behaviours‘, because they are carried out to help the person feel less anxious – at least in the short-term.

Unhelpful safety behaviours include:

-

• misuse of medication or alcohol: for example, taking a sleeping tablet, not for sleep but to block emotions just before going into a scary situation (such as out of the front door in someone with agoraphobia);

-

• acting differently during times of anxiety: for example, hurrying out of a shop; noticing a rapid heartbeat and, fearing collapse, sitting down (Reference Clark, Hawton, Salkovskis and KirkClark, 1990); always carrying a mobile phone when out shopping to ring for help if necessary.

-

• using distraction techniques: for example, mental arithmetic or physical tasks such as clenching hands or controlling breathing to try to control symptoms of anxiety;

-

• reassurance-seeking behaviour, characterised by repeatedly seeking reassurance that everything is all right and that nothing unpleasant or dangerous is going to happen: for example, ‘Doctor, am I going to die?‘, ‘Have you met other people with these symptoms?‘ Other reassurance-seeking behaviours include scanning television, newspapers and the internet for information regarding their condition, reading medical books to check the causation of specific symptoms and repeatedly visiting a GP or casualty department to have symptoms medically evaluated. People who become very reassurance-seeking and dependent on others are often so demanding that family and friends begin to withdraw from them, resulting in social isolation.

Each of these actions makes individuals feel better in the short term (which is why they are done). However, such behaviour may quickly backfire and can worsen how they feel in the medium to long term. Unhelpful behaviours can have both direct and indirect negative effects. The direct results of, for example, alcohol misuse, overspending, sexual promiscuity and isolation from friends are obvious. However, the indirect result of unhelpful behaviours is to teach unhelpful rules such as ‘I only coped because of my friend/the extra tablet/getting out of the shop and sitting down.‘A ‘vicious circle of unhelpful behaviour‘ may thus be created (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 The vicious circle of unhelpful behaviour (after Reference WilliamsWilliams et al, 2001a)

Identifying the vicious circles

Ask the right questions

Asking effective questions can help your patients to identify their own vicious circles. As with all interviewing approaches, it is best to begin with open questions, introducing closed questions only when appropriate. The following three key questions will identify the presence of each of the vicious circles:

-

• Reduced activity: ‘What have you stopped or reduced doing as a result of feeling depressed and/or anxious?‘

-

• Avoidance: ‘Is there anything you can't do, anywhere you can't go or anyone you can't see as a result of your anxiety?‘

-

• Unhelpful behaviour: ‘What have you started or increased doing as a result of feeling depressed and/or anxious to help block how you feel?‘

Use patient checklists

Short checklists such as that shown in Table 1 can allow a patient to quickly identify altered behaviour. Blank checklists for identifying the vicious circles of reduced activity, avoidance and unhelpful behaviour may be downloaded for use with patients or in teaching from http://www.calipso.co.uk.

Table 1 Checklist in identifying Jane's vicious circle of reduced activity∗

| Activity or behaviour | Have you noticed this? |

|---|---|

| Going out/socialising less | Yes. I've stopped meeting up with lots of friends |

| Poor or reduced self-care (e.g. washing less, paying less attention to your appearance, wearing same clothes for longer, not shaving or combing your hair) | |

| Neglecting food – eating less or eating more ‘junk‘ food or food that takes little preparation | |

| Stopping/reducing doing hobbies/interests such as reading or other things you previously enjoyed or did to relax | |

| ‘Letting things go‘ around the house | Yes. I just don't feel like cleaning any more |

| No longer answering the phone or the door | Yes. I certainly don't answer the door – I wouldn't have anything to say |

| Not opening or replying to letters/bills | |

| Less interested in sex; pushing your partner away physically |

Look at specific occasions when the patient felt worst

A useful way of identifying any altered behaviour is to examine in detail with the patient a particular past occasion when he or she felt worst and identify any changes in what he or she did (Box 1). This process builds on the information gathered as part of the thought investigation worksheet described by Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams & Garland (2002b).

Box 1 Identifying altered behaviour

Questions that establish the presence of altered behaviour

‘Can you recall a time during the past week when you have felt especially depressed?‘

‘What time was it, where were you, who were you with and what were you doing?‘

‘At what point did you feel most upset?‘

‘How strongly would you rate that feeling, on a scale of 0 to 100 where 0 is feeling no depression at all and 100 is the most depressed you have ever felt?‘

‘What effect did how you felt then have on what you did at the time?‘

‘What on that occasion did you do to cope with your feelings of anxiety and/or depression?‘

Questions that show whether their behaviour then worsened and their short- and longer-term feelings

‘What impact do you think that experience had on you in the short and longer term?‘(e.g. ‘What are the short- and long-term effects of never going out alone when you feel depressed?‘)

‘Is this likely to be helpful or unhelpful over the next few days, weeks and months?‘ (e.g. ‘In what way is never going out alone when you feel depressed helpful or unhelpful in dealing with your problems?‘)

Altered behaviour can be quite subtle. For example: reduced activity may involve not answering the telephone or leaving bills unopened; avoidance may be manifest in going only to smaller shops at quieter times; unhelpful behaviours include cutting someone off short in conversation, sitting down half way round the shop and asking others questions all the time while on the bus.

A useful method for deciding if a behaviour offers the patient reassurance or safety is to ask ‘If you hadn't carried out that behaviour what do you think would have happened?‘

Identify the vicious circle (if present) as a target for change

The identification of a vicious circle is not just of theoretical interest; it is identified because it is part of the problem of depression or anxiety, and consequently reversing it can be an effective treatment.

Overcoming the vicious circles

Whatever originally led individuals to feel as they currently do, their anxiety and depression can be maintained or even worsened by the unhelpful thinking styles and unhelpful behaviour that have now become part of the problem. Most patients will be able to identify that they need to try to break the vicious circle in order to improve how they feel. The challenge is how best to do this. The Five Areas Assessment model uses a seven-step approach to planning how to overcome these problems (Box 2). This approach tackles just one problem at a time using a stepwise plan and is based on the problem-solving approach inherent to CBT.

Box 2 The seven-step approach

Step 1 Identify the problem to be tackled and define it as clearly and precisely as possible

Step 2 Think up as many solutions as possible

Step 3 Consider the advantages and disadvantages of each of the possible solutions

Step 4 Choose one of the solutions

Step 5 Plan the steps needed to carry it out

Step 6 Carry out the plan

Step 7 Review the outcome

The seven-step approach can be used to plan ways of overcoming problems of reduced or avoided activity, or to reduce unhelpful behaviour such as drinking. Case vignette 1 (modified with permission from Reference Williams, Richards and WhittonWilliams et al, 2002) shows how the seven-step approach can be used to overcome an example of reduced activity. Case vignettes 2 and 3 describe its use in longer-term strategies against avoidance and unhelpful behaviour.

Case vignette 1: Overcoming reduced activity

Jane is 40 years old, lives alone and has been feeling depressed and moderately anxious for about 6 months. When she fills in the screening checklist (Table 1) she identifies that she has several areas of reduced activity. She is then asked the following three questions: (1) ‘Have you stopped doing things you used to enjoy as a result of how you feel?‘; (2) ‘Has this removed things from life that previously gave you a sense of pleasure/achievement?‘; (3) ‘Overall, has this worsened how you feel?‘ Her affirmative answers to all three questions reveal to Jane that she is experiencing a vicious circle of reduced activity. Jane is therefore led through the seven-step approach.

Step 1 The important first step is to make sure that Jane identifies a single, clearly defined initial target problem. This step is particularly important as she currently feels overwhelmed by several different problems. It is important that she chooses a target problem that: (1) will be useful for changing how she is; (2) is specific , so that she will know when she has overcome it; (3) is realistic, practical and achievable.

Jane identifies several areas of reduced activity, but it is not possible to overcome all of these areas at once. Instead, she needs to choose just one area on which to focus to begin with – this means putting the other areas to one side for the time being. Jane decides that the specific area of reduced activity that she is going to focus on is that she has stopped meeting up with lots of friends.

Step 2 Think up as many solutions as possible. A difficulty that people often face when they have chosen which initial problem area to focus on is that they cannot see any ways of dealing with it. It can seem too difficult even to start tackling it. One way around this is to try to step back from the problem and see if any other approaches are possible. This approach is called ‘brainstorming‘.

In brainstorming, the more solutions that are generated, the more likely it is that a good one will emerge. Even ridiculous ideas should be included, as they can help you to adopt a flexible approach to the problem. Useful questions to help you to think up possible solutions might include: ‘What ridiculous solutions can I include as well as more sensible ones?‘; ‘What helpful ideas would others (e.g. family, friends or colleagues at work) suggest?‘; ‘What approaches have I tried in the past in similar circumstances?‘; ‘What advice would I give a friend who was trying to tackle the same problem?‘

Jane lists on a piece of paper possible ways she could start to meet up with her friends again. Solutions may be simple (telephone her friend Sarah) or more ambitious (hire a hall and a band and invite all her friends to a party). The aim here is simply to list as many potential solutions to the problem as possible. Clinicians need to be mindful of the fact that impaired problem-solving skills are characteristic of depression and therefore they may need to be very proactive with the patient in generating this list (Reference Nezu, Nezu and PerriNezu et al, 1989). This said, it is important for patients to be given the opportunity to participate fully in the process so that the solutions considered are ones that they agree with. Remember, particularly in depression, that thinking processes are slowed and negatively biased, so that what might seem like a straightforward plan to you the clinician may seem an impossible hurdle to the patient. Also, you may need to slow the pace in order to engage the patient. At this stage no option should be ruled out and, no matter how ridiculous, every suggestion should be included on the list. This provides opportunity for the injection of some humour into the session as clinician and patient give vent to their imaginations.

Step 3 Look at the advantages and disadvantages of each of the possible solutions. The aim here is to examine the feasibility of each solution on the list. Ideally, a summary of this process should be written down: given the thinking changes characteristic of depression and anxiety, it is unlikely that the patient will have the capacity to retain in memory the details of an intervention. This process should enable clinician and patient to work together to eliminate solutions that are not feasible, impractical or are too difficult to implement at present and to choose a single solution that is realistic and achievable and can be implemented in the following week or two.

Jane's list of suggestions, advantages and disadvantages is shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Jane's list of possible solutions and their advantages and disadvantages

| Suggested solution | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Hire a hall and a band and invite all my friends to a party. | I'd meet lots of people and it might be fun. | The idea is far too scary. I know I couldn't cope with it at the moment. Anyway, it would cost a fortune and I can't afford that sort of thing. |

| Ask my friend Sarah round for coffee. | I like Sarah and it would be nice to catch up. She's been on holiday and I want to know whether she met anyone. | This is only a little bit scary, but how would the conversation go? There may be long embarrassing silences. |

| Phone my friend Sarah. | We always used to natter by phone and we used to enjoy it. She's one of my oldest friends, so it would probably be easy. | I haven't spoken to her for at least 2 months and I'm not sure what we would talk about. |

| Have a meal out with friends at the local Indian. | I like curry and it would give me a chance to meet up with others for at least 2 hours. | Again, I'm not so sure about this. It feels like this might be going a step too far. It might feel like a very long night, and I'm not sure I can cope. |

| Cook a meal at home and invite some friends. | I like cooking and it would give a focus for me to work towards. | It could go wrong – it would put me under a lot of pressure getting all the food in. I'm not sure how many people I should invite. This seems quite stressful. |

Step 4 Choose one of the solutions. The chosen solution should be realistic and likely to succeed and the decision will be based on answers to Step 3. Jane decides to phone her friend Sarah.

It is important that the initial solution is something that will help Jane to tackle her target problem and that she is realistic in her choice, so that it does not seem impossible for her. Jane can subsequently build on this initial target for change with additional targets that will help her to move forwards.

Step 5 Plan the steps needed to carry it out. This is a key stage and is something that many people have difficulty completing to begin with. Jane needs to generate a clear plan that will help her to decide exactly what she is going to do and when she is going to do it.

It is useful for Jane to write down the steps needed to implement the solution and to be specific about what she will do. This will help her to remember what to do and allows her to predict possible blocks and problems that might arise. Table 3 shows five ‘questions for effective change‘ and Jane's reflections on them. These questions should always be asked as part of the fifth step of the problem-solving approach as they can help patients to recheck how practical and achievable a plan is.

Table 3 Jane's reflections on five questions for effective change (after Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001a)

| Question | Your reflections |

|---|---|

| 1. Will it be useful for understanding or changing how I am? | Even though I worry how the conversation will go, I think it will be useful for me to do this anyway. I think this is an important thing for me to change and it will get me back into contact with someone I like. |

| 2. Is it a specific task, so that I will know when I have done it? | I'm clear what I am going to do – I'll phone her up this evening. That way I'll definitely know whether I have done it or not. |

| 3. Is it realistic: is it practical and achievable? | Yes, it is realistic, I can do that. I'd be lying if I didn't admit that the idea scares me a bit because I don't know what she'll say to me, but it's really only a little bit scary – I am sure I can do this. |

| 4. Does it make clear what you are going to do and when you are going to do it? | I'll phone her this evening, after 7 o'clock– she will be home from work then. |

| 5. Is it an activity that won't be easily blocked or prevented by practical problems? | What might block it? Maybe she won't be in when I phone. If so, I'll phone again later tonight, or try tomorrow. I'm also worried that there may be gaps in the conversation and that will be very embarrassing. I'll get around that by writing down 3 or 4 things we could talk about. I could ask her about the holiday – where she went, the hotel, beaches and food. I also want to know if she had a good time, and whether she met anyone. I need to plan out how to ask that! The only other thing that I can predict could prevent me doing this is if I lose my nerve and put off calling her tonight, but I think it'll be all right. |

The aim of these questions is to equip patients with skills for devising effective plans for tackling problems and identifying the factors that play a part in maintaining their problems. The questions try to help patients to anticipate problems and think flexibly about maximising the chances of a solution activity occurring. Once more, these strategies are inherent to the problem-solving stance of CBT.

Jane's goals are clear, specific and her target is realistic. She knows what she is going to do and when she is going to do it. She has predicted potential difficulties that might get in the way. This seems to be a well-thought-through plan.

Step 6 Once Jane's plan is complete, she should carry it out. Jane phones Sarah that evening. Sarah is out and Jane has an immediate negative thought: ‘I knew she'd be out – what's the point?‘ However, she thinks back to her plan and decides to do what she had planned if Sarah was out. She therefore phones again later that evening and finds that Sarah is in. Sarah is delighted to hear from Jane and they chat for over half an hour. They have so much to talk about that Sarah asks if they can chat again the next day. Overall, Jane realises that she has gained some pleasure from the conversation and a definite sense of achievement and that her predictions about how it would go wrong were unfounded.

Step 7 Jane should now review the outcome, looking at what happened when she carried out her plan. Was her plan successful in tackling her original target problem (to meet people again)? Did her plan go smoothly, or were there any difficulties? What has she learned from carrying out her plan? Jane answers in the affirmative to the first two questions, and notes the following in answer to the third:

‘That went really well. I almost gave up when Sarah wasn't in. I'm really pleased that I stuck to the plan and phoned her back. The two things I've learned are: (1) just how useful it is to have predicted that Sarah might not be in when I phoned. When that happened it was discouraging, but it wasn't a great shock. I quickly challenged my initial negative reaction and phoned again later. (2) All my concerns about it being very embarrassing and anxiety-provoking weren't real. I did feel anxious when I got through to her, but I noticed that the anxiety quickly began to fall as we chatted.‘

In this ideal scenario, Jane's plan went smoothly. As all clinicians are only too acutely aware, this is often not the case for the patients we see in clinic. However, one of the important tenets of CBT is the notion that everything that occurs – successful or problematic – can be a useful learning aid. So even when plans go badly awry, it is important to recognise that something can still be learned from this. Thus, when faced with such a scenario the clinician needs to work with the patient to identify the reasons why things went wrong, restructure the plan accordingly and implement its revised version the following week.

Building on what has been learned The next key stage is for Jane to build on what she has done by developing a clear plan to move things forward still further. To do this, she needs to think about her short-, medium- and longer-term targets/goals. The key is to build one step upon another, so that each time she has planned and completed each target in the seven-step approach she can consider what the next target will be. Without this sort of approach she may find that, although she takes some steps of progress, these are all in different directions and she loses her focus and motivation as a result.

The key is to do everything at the right pace, so that change happens, but not so quickly that it seems overwhelming. For example, Jane might plan to work through the following targets over a period of weeks (Table 4).

Table 4 Jane's step-by-step weekly targets

| Target | Time scale |

|---|---|

| 1. Phone Sarah | Week 1 |

| 2. Phone other old friends and acquaintances | Week 2 |

| 3. Arrange to meet Sarah at my flat | Week 3 |

| 4. Go for a curry with Sarah | Week 4 |

| 5. Arrange to meet a few people for a meal in a restaurant | Weeks 5 & 6 |

| 6. Ultimate target: have 3 or 4 friends round to my flat for a meal | Week 7 |

Case vignette 2: A longer-term strategy to overcome avoidance

We met Mark in the third paper in this series (Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams & Garland, 2002b ). He is experiencing panic attacks whenever he goes to a supermarket or large shop, so he has started to avoid them. He misinterprets his physical symptoms of over-arousal as evidence that he is about to collapse. The treatment plan aims to help him to test out the accuracy and helpfulness of his predictions of catastrophe and to plan a step-by-step approach to facing up to his fears.

Mark uses a step-by-step approach to plan targets that he needs to meet over the next few weeks (Table 5). This table exemplifies two key elements of this approach: first, it identifies and challenges the fears that underlie Mark's anxiety and avoidance; and second, it gives a step-by-step plan for overcoming the avoidance. This also provides Mark with the opportunity to further test out and challenge his fears.

Table 5 Mark's step-by-step weekly targets to overcome his initial prediction that he will collapse if he goes into a supermarket (after Reference Williams, Richards and WhittonWilliams et al, 2002)

| Target | Initial fear level before starting the plan | Belief in initial prediction after completion of target behaviour | Time scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Going into the local shop for a paper, walking round slowly, and staying there for at least 10 minutes | Hardly scary at all (5–10% scary) | 100% | Week 1, at least three times that week |

| 2. Going into the local shop at a busier time of day, walking round slowly, staying in the shop for at least 20 minutes each time | A little scary (15% scary) | 90% | Week 2, at least three times that week |

| 3. Queuing in the post office, deliberately choosing the longest queue | Quite scary (35% scary) | 85% | Week 3, at least twice that week |

| 4. Going into the supermarket foyer area to buy a newspaper and staying there for at least 20 minutes | Pretty scary (50% scary) | 80% | Weeks 4 & 5, at least twice a week |

| 5. Going into the supermarket at a quieter time and shopping for at least 30 minutes | Moderately scary (75% scary) | 80% | Week 6, at least three times that week |

| 6. Shopping in the supermarket at a busier time by myself for at least 40 minutes | Very scary (85% scary) | 60% | Week 7, at least twice that week |

| 7. Ultimate target: shopping in the super-market by myself for at least 1 hour at a busy time, choosing the longest queue | Very very scary (100% scary) | 20% | Week 8, at least twice that week |

Mark's plan is made up of seven separate targets, each of which can itself be planned out in detail using the same seven-step approach. Each step acts as the next target, building on the previous one to help Mark to move forwards. Over a number of weeks this can add up to a very significant total change in what he is able to do. In repeatedly completing each step Mark must be careful that he does not attempt to block his fear with unhelpful safety behaviours, for example by rushing round the shop as quickly as possible or only going shopping when accompanied by a friend. Mark would need to plan to reduce and stop any such behaviours, for example by walking slowly round each shop, alone and allowing himself to experience the anxiety and not hurry from it. By doing this he can test out his fears concerning collapse. Each time he repeats each step, his anxiety will be less intense and last for a shorter time than before. He will consequently find that going to the supermarket becomes less anxiety-provoking.

In Table 5, Mark rates the steps taken in terms of how scary and difficult they seem. The plan helps Mark to face up to his fear in a graded and paced way, so that he never feels so anxious that he wants to give up. He needs repeatedly to succeed at each step before moving on to the next one. By repeating each new step several times each week, Mark can build up his confidence before moving on to the next the following week. If he finds that a particular stage is too difficult, he can take a step back, and re-plan the next task using the questions for effective change (Table 3).

Mark has addressed in his plan his more subtle areas of avoidance (e.g. choosing to go to the shop at a quieter time) and unhelpful safety behaviours (e.g. rushing round the shop when he is there). Exactly the same principles of planning may be used to tackle these as are applied to the more obvious avoided areas.

Thus, the step-by-step approach helps Mark test out his fears and to discover that they are both unhelpful and untrue.

Case vignette 3: A longer-term strategy to overcome unhelpful behaviour

The same approach can also be used to overcome unhelpful behaviour. John has realised he has a general problem: he is drinking too much. His specific target is to reduce his drinking over the next 2 months to only two glasses of wine a week. He needs to write a clear step-by-step plan that is likely to be successful. He sees his doctor to discuss this, and together they agree the strategy shown in Table 6.

Table 6 John's strategy to overcome the problem behaviour of drinking too much

| Reduction strategy | Units/week 1 | Time scale |

|---|---|---|

| Three bottles of wine at home by myself four times a week | 72 | Week 1 |

| Two bottles of wine at home four times a week | 48 | Week 2 |

| Two bottles of wine at home three times a week | 36 | Week 3 |

| One and a half bottles of wine at home three times a week | 27 | Week 4 |

| One bottle of wine at home three times a week | 18 | Week 5 |

| Four glasses of wine at home three times a week | 12 | Week 6 |

| Two glasses of wine at home twice a week | 4 | Week 7 |

| Target behaviour: Drinking only one glass of wine twice a week | 2 | Week 8 |

John then uses the seven-step approach to plan each step, so that he has a clear written plan of what he will do each week. He manages to keep to his plan for the first few days and feels quite good about himself and how things are going. However, things do not go according to plan when he goes to a work party. After two cans of drink he thinks ‘What the heck, let your hair down.‘ He ends up drinking ten pints of beer in a binge and has to take a taxi home. The next day he wakes up feeling awful and thinks about giving up the planned reduction in drinking completely. But after a few hours, he begins to think about what he has learned from his doctor about having to stick to a clear plan if he is going to succeed. He also remembers his doctor telling him that it is likely that there will be occasional set-backs, but that it can still work out for the good: he can learn from what happens and plan to avoid making the same mistake again. John therefore tries again and restarts his plan. He finds that he is able to reach his target over the next few weeks.

John's medium-term plan is made up of eight separate steps, and each step can be planned out in detail using the seven-step approach.

Full worked examples of these approaches are available as a series of patient workbooks (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001a ).

Conclusions

The step-by-step approach (summarised in Box 3) can be successfully used to tackle many different problems. For example, to:

-

• reintroduce more activities that lead to a sense of pleasure and achievement;

-

• overcome avoidance that has occurred as a result of anxieties or phobias such as a fear of spiders, going on buses or talking to others;

-

• reduce a single unhelpful behaviour such as drinking, excessive reassurance-seeking or retail therapy for depression or anxiety.

The approach can also be integrated with other CBT treatments such as problem-solving and identifying and challenging extreme and unhelpful thoughts.

Box 3 The step-by-step approach: a summary

-

1. Break the problem behaviour down into smaller parts and clearly identify a specific first goal

-

2. Use the seven-step approach to plan to achieve this initial goal

-

3. Use the questions for effective change to plan each step. Ensure that the plan is practical and achievable

-

4. Build on this by planning short-, medium- and longer-term target goals. Use the seven-step plan for each step along the way

-

5. There can be as many or as few steps as you and the patient want in the step-by-step plan

-

6. Do not try to move too quickly from one step to the next. Make sure that the patient repeatedly succeeds at each step before proceeding to the next

-

7. Remember that pacing is the key. Your patient should move forward at a pace that he or she can cope with. If any step is too difficult, the patient should go back a stage to regain confidence, then decide on a different next step that is not quite so difficult – plan this new step out using the questions for effective change

-

8. The main reasons that a plan is ineffective is that it is too ambitious and that the patient believes change to be impossible

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Effective ways in which patients can reduce unhelpful behaviours include:

-

a creating a clear plan to reduce the behaviour

-

b deciding to do something about it

-

c planning an immediate cessation of the behaviour

-

d including relatives or friends in the plan to help maintain the goal of reducing the unhelpful behaviour

-

e predicting possible problems with the plan and looking at ways of responding if things do not go well.

-

-

2. Behaviours that can worsen or maintain symptoms of phobic anxiety include:

-

a avoidance

-

b trying to overcome fears in a planned way

-

c drinking a lot of caffeine-containing drinks

-

d seeking reassurance from relatives

-

e using alcohol to block symptoms of anxiety.

-

-

3. The seven-step approach:

-

a can be used to tackle avoided and reduced activity

-

b emphasises the need to tackle several different problems at one time

-

c uses brainstorming techniques to produce a range of possible solutions

-

d encourages patients to deal with their problems entirely by themselves

-

e most often fails because the plan has not clearly defined the problem to be tackled.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | T | a | T |

| b | F | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | F |

| e | T | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.