Introduction

Tapeworms belonging to the species complex of Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato (s. l.) have been identified as the cause of a chronic zoonotic disease known as cystic echinococcosis (CE), a disease that has considerable impact on both livestock and human health worldwide (Craig et al., Reference Craig2017; WHO, 2017). The general life cycle of E. granulosus s. l. involves various carnivores as definitive hosts for the adult stage, including mostly dogs in both rural and urban areas, and wolves (Moks et al., Reference Moks2006; Schurer et al., Reference Schurer2014; Laurimaa et al., Reference Laurimaa2015a; Thompson, Reference Thompson2017). Both domesticated and wild large mammalian herbivores act as intermediate hosts for the larval stage. The larval stage is in the form of hydatid cysts that are predominantly located in the liver and/or lungs of the intermediate hosts. Cysts can be fertile or sterile, depending on presence or absence of protoscoleces, respectively. While these cysts can cause significant health problems for the infected intermediate hosts, the infection in the definitive host is usually asymptomatic (Thompson, Reference Thompson2017).

The taxonomy of E. granulosus s. l. has been a challenging issue for decades. It is well established that this parasite complex displays high genetic diversity and on the basis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) it has been divided into eight different genotypes (G1, G3, G4–G8; and G10; Bowles et al., Reference Bowles, Blair and McManus1992, Reference Bowles, Blair and McManus1994; Lavikainen et al., Reference Lavikainen2003; Kinkar et al., Reference Kinkar2017). Several of these recognized mitochondrial genotypes have differences in their lifecycles, hosts ranges and morphology (Thompson and McManus, Reference Thompson and McManus2002; Romig et al., Reference Romig2017; Thompson, Reference Thompson2017). These differences have provided grounds to consider some of these genotypes as distinct species: G1 and G3 as E. granulosus sensu stricto (s. s.; Kinkar et al., Reference Kinkar2017), G4 as Echinococcus equinus and G5 as Echinococcus ortleppi (Thompson and McManus, Reference Thompson and McManus2002; Lymbery, Reference Lymbery2017). The analytical power has been low in most studies as the analyses have been based largely on short sequences of mtDNA, most often on a fragment of a single gene (e.g. Casulli et al., Reference Casulli2012; Andresiuk et al., Reference Andresiuk2013). Recent studies based on considerably longer mtDNA sequences (Kinkar et al., Reference Kinkar2016, Reference Kinkar2018a, Reference Kinkar2018b; Laurimäe et al., Reference Laurimäe2016) have yielded significantly deeper insight into the phylogeny and phylogeography of different genotypes. For example, using sequences of nearly complete mitochondrial genomes and three nuclear genes, Kinkar et al. (Reference Kinkar2017) have revised the status of E. granulosus s. s. and demonstrated that genotypes G1 and G3 are distinct mitochondrial genotypes, whereas G2 is not a separate genotype or even a monophyletic cluster, but belongs to G3. On the other hand, nuclear data revealed no genetic separation of G1 and G3, suggesting that these genotypes form a single species due to ongoing gene flow. The authors concluded that in the taxonomic sense, genotypes G1 and G3 can be treated as a single species E. granulosus s. s., and that G1 and G3 should be regarded as distinct genotypes only in the context of mitochondrial data, whereas G2 was recommended to be excluded from the genotype list (Kinkar et al., Reference Kinkar2017). A recently discovered isolate from Ethiopia is tentatively retained in E. granulosus s. s. as a genotype distant from G1/G3 awaiting taxonomic positioning (Wassermann et al., Reference Wassermann2016). In contrast, the species status of E. equinus (G4), E. ortleppi (G5) and Echinococcus felidis has, to date, remained undisputed (Hüttner et al., Reference Hüttner2008; Thompson, Reference Thompson2008; Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp2011; Romig et al., Reference Romig, Ebi and Wassermann2015; Lymbery, Reference Lymbery2017).

The species status of the four E. granulosus s. l. genotypes G6, G7, G8 and G10, however, has remained uncertain. In addition to genetic differences, there are also various ecological and epidemiological differences between these mitochondrial genotypes. Genotypes G6 and G7 are known to be perpetuated predominantly in a domestic life cycle involving goats, camels or pigs as intermediate hosts, and dogs as definitive hosts; however, a recent study found members of the G6/G7 cluster to be widespread in wild mammals of southern Africa (Romig et al., Reference Romig2017). Genotypes G8 and G10 are mostly circulating in a sylvatic cycle with moose and reindeer acting as intermediate hosts, and wolves as definitive hosts. Moreover, these four genotypic groups are largely allopatric. The distribution range of G6 and G7 covers more southern areas such as Western Europe, the Mediterranean area, Africa, South and Central America, and the Middle East (e.g. Varcasia et al., Reference Varcasia2006, Reference Varcasia2007; Lymbery et al., Reference Lymbery2015). Genotypes G8 and G10 have been found to coexist in the northern hemisphere – mostly in northern part of Europe (e.g. Estonia, Finland, Sweden and Latvia), Northern Asia and Canada (Moks et al., Reference Moks2006, Reference Moks2008; Konyaev et al., Reference Konyaev2013; Schurer et al., Reference Schurer2014; Marcinkute et al., Reference Marcinkute2015; Oksanen and Lavikainen, Reference Oksanen and Lavikainen2015).

Previous studies have mostly focused on mtDNA to resolve the phylogeny and taxonomic status of genotypes G6–G10 (e.g. Moks et al., Reference Moks2008; Nakao et al., Reference Nakao2013; Addy et al., Reference Addy2017). These studies demonstrated that the cervid genotype G10 is a sister taxon to the camel–pig genotypes G6/G7, rather than assuming a sister position with the other cervid genotype G8. It was therefore suggested to combine G6–G10 into a single species which, in terms of priority, should be E. canadensis (Nakao et al., Reference Nakao2007; Hüttner et al., Reference Hüttner2008). Moreover, the mitochondrial studies placed E. multilocularis in the midst of the E. granulosus genotypes, rendering the E. granulosus complex paraphyletic and contradicting the classical taxonomy of the genus (reviewed in Knapp et al., Reference Knapp2015). Although mtDNA sequences are widely used and various parasite identification methods have been developed based on these (e.g. Boubaker et al., Reference Boubaker2013; Laurimaa et al., Reference Laurimaa2015b) one has to be cautious when interpreting the results. MtDNA represents the evolution of the maternal linage, which can have different trajectories than that of the species. As argued in Saarma et al. (Reference Saarma2009), once a new mtDNA mutation becomes fixed in a population, the new mitochondrial lineage separates from the ancestral one; from this point onwards, mutations continue to fix progressively in an independent manner in both the new and ancestral mitochondrial lineages, and mitochondrial lineages continue to diverge. However, this does not mean that these separate mitochondrial lineages have necessarily become separate biological entities – genetic exchange between different taxa can only be assessed with nuclear markers. Thus, it was clear that nuclear data are needed to clarify the taxonomy of the genus Echinococcus. Indeed, a phylogeny radically different from that of mtDNA data was inferred by using sequences of five nuclear genes (5086 bp in total); this analysis placed G8 and G10 as sister taxa, and E. multilocularis clearly separate from the E. granulosus s. l. complex (Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009). However, in this work G6/G7 were represented by isolates from cattle and pig, and it was not evident which of these two genotypes these isolates belonged to (probably G7). Since the clear distinction between G6 and G7 was not made in this study, the exact phylogenetic relations between G6 and G7 remained obscure. On the other hand, the analysis performed by Knapp et al. (Reference Knapp2011) based on a different set of nuclear loci suggested (in line with the mtDNA data), that E. granulosus s. l. complex could be paraphyletic. Unfortunately, this study did not include G10 and therefore the exact phylogenetic relations in the G6–G10 group remained unresolved. Thus, despite numerous attempts to revise the phylogeny and taxonomy of genotypes G6–G10, no consensus has been reached. Some authors have proposed to treat G6–G10 provisionally as a single species E. canadensis awaiting further data from the nuclear genome (e.g. Nakao et al., Reference Nakao2007; Moks et al., Reference Moks2008; Nakao et al., Reference Nakao2013; Romig et al., Reference Romig, Ebi and Wassermann2015; Addy et al., Reference Addy2017), while others as two distinct species: G6/G7 as E. intermedius and G8/G10 as E. canadensis (Thompson, Reference Thompson2008; Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009) or even as three species: G6/G7 as E. intermedius, G8 as E. borealis and G10 as E. canadensis (Lymbery et al., Reference Lymbery2015).

The main aim of this study was to use a more extensive range of nuclear loci and include all four genotypes (G6–G8 and G10) in a phylogenetic analysis to resolve their taxonomic status.

Materials and methods

Parasite material

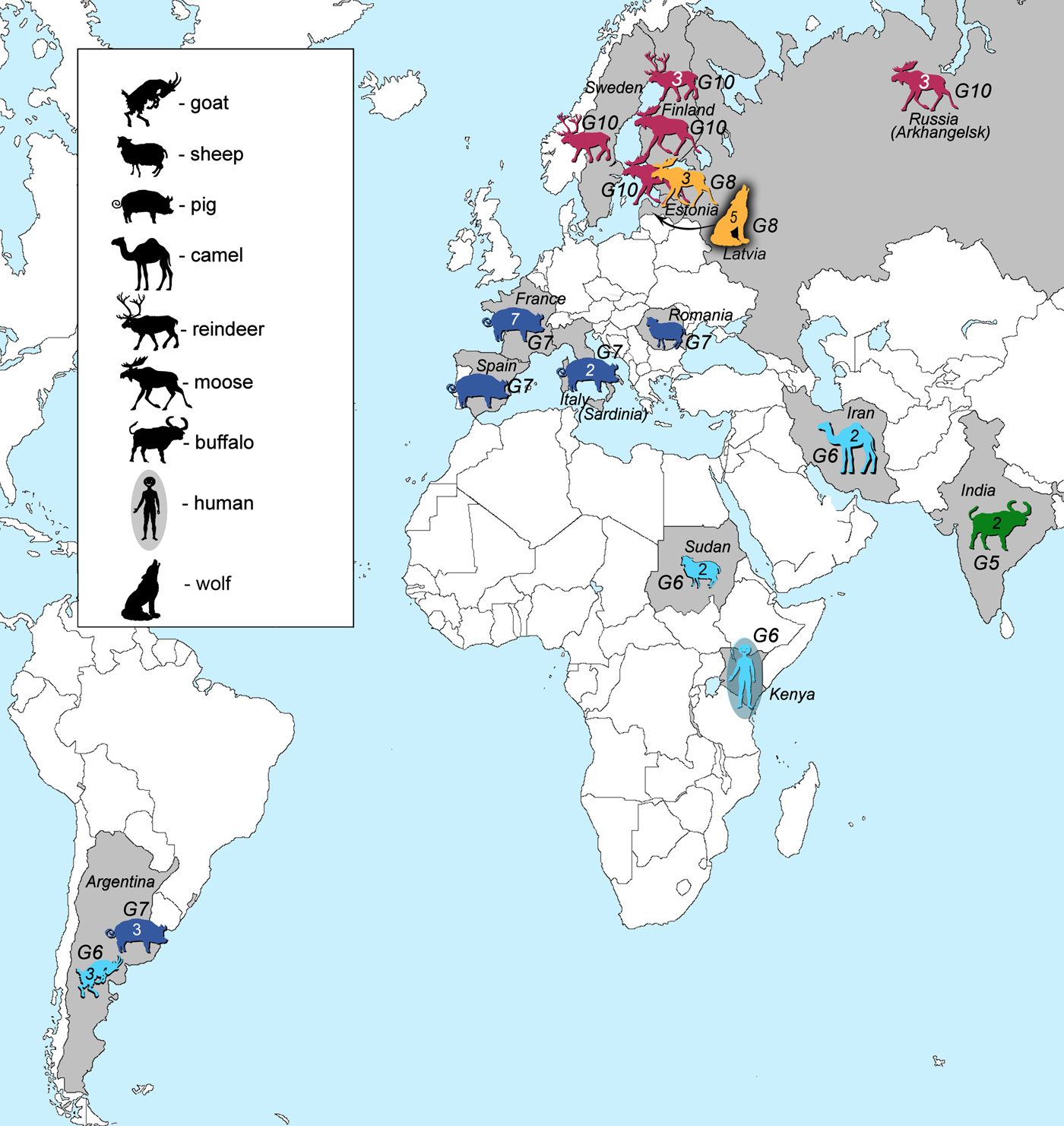

Samples of E. granulosus genotypes G5–G10 used in this study (41 in total) originated from various regions and intermediate or final hosts (Fig. 1, Table 1). Genotype G5 was represented by two samples from India. Samples of genotype G6 (n = 8) were from three continents: South America (Argentina, n = 3), Africa (Kenya, n = 1; Sudan, n = 2) and Eurasia (Iran, n = 2). Samples of genotype G7 (n = 14) were from South America (Argentina, n = 3), and Eurasia (Spain, n = 1; France, n = 7; Italy, n = 2; Romania, n = 1). Samples that belonged to genotype G8 (n = 8) originated from Eurasia (Estonia, n = 3; Latvia, n = 5), whereas genotype G10 was represented by nine samples from Eurasia (Sweden, n = 1; Finland, n = 4; Russia, n = 3; Estonia, n = 1). DNA of the Finnish, Swedish and Russian specimens were provided by Antti Lavikainen. These specimens were already used and their genotypic identities defined in previously published studies (Lavikainen et al., Reference Lavikainen2006; Nakao et al., Reference Nakao2013). Samples were ethanol-preserved at −20 °C until further use.

Fig. 1. Geographic locations and host species (intermediate or final) of all of the analysed samples in this study. Numbers inside the animal figures stand for the number of samples collected. Green colour represents E. ortleppi (G5) samples, cyan genotype G6 samples, dark blue genotype G7 samples, orange G8 and pink G10 samples.

Table 1. Data for samples of Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato genotypes G5–G10

a Sample sequences of pepck and pold obtained from the GenBank database (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp2011).

b Sample sequences of ef1, cal, tgf and elp obtained from the GenBank database (Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009).

PCR amplification and sequencing of six nuclear loci

High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was used to extract DNA from either protoscoleces or cyst membranes, following the manufacturer's protocols. Six nuclear genes were chosen for PCR amplification and sequencing: transforming growth factor beta receptor kinase (tgf; 1137 bp), calreticulin (cal; 1138 bp), elongation factor 1 alpha (ef1; 1055 bp), ezrin–radixin–moesin-like protein (elp; 780 bp), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (pepck; 1506 bp) and DNA polymerase delta (pold; 1771 bp). For further details on cycle parameters for PCR and sequencing see Saarma et al. (Reference Saarma2009; tgf, cal, ef1, elp) and Knapp et al. (Reference Knapp2011; pepck, pold). Nuclear sequences were deposited in GenBank (MG766944–MG767169). Consensus sequences were assembled using Codon Code Aligner v6.0.2. BioEdit v7.2.5 (Hall, Reference Hall1999) was used for multiple alignments with Clustal W and for manual correction of sequences.

As polymorphic sites where the same mutations are shared between genotypes G6 and G10 have been found in pepck and pold genes (Yanagida et al., Reference Yanagida2017), we also checked our aligned sequences for polymorphic sites that discriminate between genotypes G6 and G10, as well as for positions where mutations were shared between these genotypes.

Bayesian phylogeny

Bayesian phylogenies were constructed for two datasets, both based on six nuclear genes (7387 bp in total): (1) Dataset 1 (a total of 40 sequences): 39 samples of G6–G8 and G10 analysed in this study, and one additional G8 sample from GenBank, originating from the USA (accession numbers for pepck and pold were FN567995 and FN568366, respectively; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp2011); (2) Dataset 2 (a total of 42 sequences): the same set of samples as in Dataset 1 and two additional sequences of genotype G5.

The best-fit nucleotide substitution model was selected on the basis of BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) scores using jModelTest 2 (Guindon and Gascuel, Reference Guindon and Gascuel2003; Darriba et al., Reference Darriba2012). Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed in BEAST 1.8.4 (Drummond et al., Reference Drummond2012) using StarBeast (Heled and Drummond, Reference Heled and Drummond2010). Posterior distributions of parameters were estimated by using the MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) sampling. Total length of the chain was 10 000 000 and the parameters were logged every 1000 generations. The resulting phylogenetic trees were summarized and annotated using TreeAnnotator 1.8.4 and visualized with FigTree 1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree).

Results

Total length of the alignment based on six nuclear loci was 7387 bp: ef1 1055 bp, cal 1138 bp, tgf 1137 bp, elp 780 bp, pepck 1506 bp and pold 1771 bp. However, a few of the samples did not yield positive results for all analysed nuclear loci, but as BEAST allows analysis with some missing data, these samples were also included in the analysis (Table 1). All of the samples were homozygotes at all six nuclear loci.

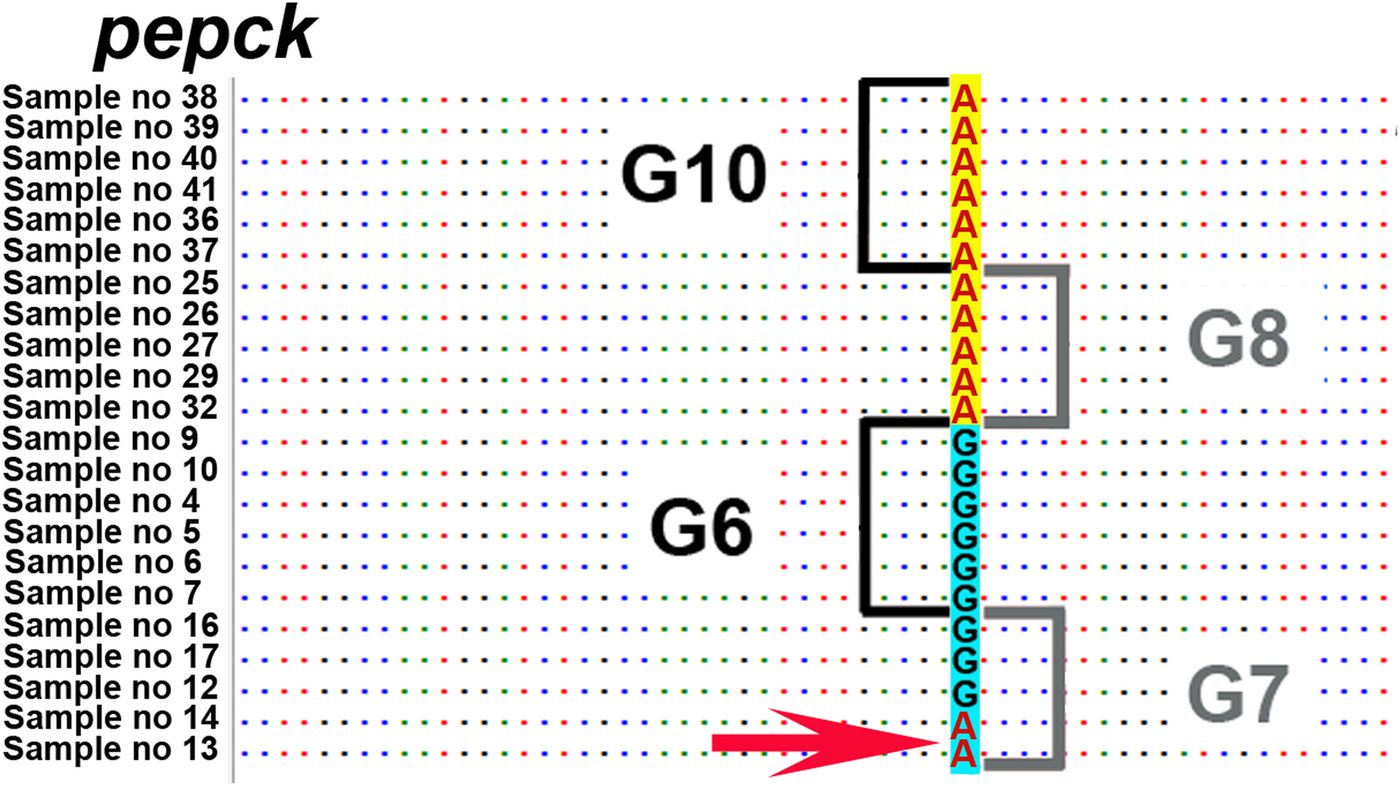

Across the six nuclear loci, 12 polymorphic positions were found that discriminated between G6/G7 and G8/G10. However, in the pepck, mutations in three positions were shared between two G7 isolates (samples 13 and 14) and G8/G10 isolates. According to GenBank reference FN567995 (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp2011) these positions were: 236; 1435–1436; 1513.

The best-fit nucleotide substitution model used for the nuclear DNA (nDNA) data was GTR + I + G. The Bayesian phylogeny for the Dataset 1 revealed that genotypes G6 and G7 formed one clade, whereas G8 and G10 another (Fig. 2). Posterior probability values for both nodes assigning G6/G7 and G8/G10 into two different clades were very high (1.00). According to the evolutionary (general lineage) species concept, they can be regarded as two distinct species.

Fig. 2. Bayesian phylogeny of genotypes G6–G8 and G10, based on sequences of six nuclear loci (Dataset 1; 40 samples). The numbers on nodes represent posterior probability values. For further details on the included samples see Table 1.

Internal nodes for the clade G8/G10 also received high posterior probability values (0.98 and 1.00). It was shown that G8b (the GenBank sample from the USA) was a sister taxon to G10d (Estonia) and that G10c was a sister taxon to the G8b/G10d clade. Additionally, the tree topology indicated that G8a was positioned as a basal taxon in relation to the G10c/G10d/G8b clade. Similarly to G8/G10 clade, the internal nodes for G6/G7 also received high posterior probability values (0.96 and 1.00). The resultant tree topology shows that G6 is a sister taxon to G7e and that G7d is sister to G6/G7e. G7c occupied a basal position inside the G6/G7 clade.

We also performed a phylogenetic analysis for the Dataset 2 (included G5), as well as with only the samples for which all six nuclear loci were sequenced (Table 1). These analyses yielded essentially the same phylogenetic relations between G6 and G10 as with the larger dataset (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S1–S3).

Discussion

A stable taxonomy of E. granulosus s. l. is essential to the medical and veterinary communities for accurate and effective communication of the role of different species in this complex on human and animal health. Despite several decades of research, the taxonomy of E. granulosus s. l. has remained controversial and a subject of intense discussion (Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp2011; Lymbery et al., Reference Lymbery2015; Nakao et al., Reference Nakao, Lavikainen and Hoberg2015). Most of the studies aiming to resolve the taxonomic status of genotypes G6–G10 have relied on mtDNA (e.g. Lavikainen et al., Reference Lavikainen2003; Nakao et al., Reference Nakao2007; Hüttner et al., Reference Hüttner2008; Moks et al., Reference Moks2008; Nakao et al., Reference Nakao2013; Addy et al., Reference Addy2017). However, the mitochondrial genome can only reveal the evolutionary history of the maternal lineage, which can be different to that of the species. For species delimitation, a key component is the analysis of genetic exchangeability, which can be effectively studied only by using various loci from the nuclear genome (Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009). Until recently, only two studies have analysed multiple nuclear loci to infer the phylogeny of E. granulosus s. l. (Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp2011), yielding contradictory results. Moreover, both studies did not include all genotypes of the G6–G10 complex.

Nuclear data and taxonomy of G6–G10

The Bayesian phylogeny based on six nuclear loci clustered the camel–pig genotypes G6/G7 into one clade and the cervid genotypes G8/G10 into another clade (Fig. 2). This result provides strong support for the hypothesis according to which genotypes G6–G10 are divided into two species (Thompson, Reference Thompson2008; Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009). The internal division of the G6/G7 and G8/G10 clades provides evidence for gene flow between G6 and G7, as well as between G8 and G10, but non-existent or very limited gene flow between genotypic groups G6/G7 and G8/G10. The latter seems to be supported by a recent study based on two nuclear loci, which suggested some degree of gene flow between genotypic groups G6/G7 and G8/G10 (Yanagida et al., Reference Yanagida2017); however, their result could be also due to incomplete lineage sorting (see below). Since G6 and G7 are not distinct taxa based on nuclear data (notice in Fig. 2 that G7e forms a subclade with G6, while other isolates of G7 are sister to this), it demonstrates that the gene flow between G6 and G7 has been sufficient to guarantee that G6 and G7 have not diverged from each other. Exactly the same is valid for G8 and G10 (notice in Fig. 2 that G8 and G10 do not form separate subclades, but the isolates of both genotypes are not monophyletic).

Gene flow can occur under conditions of sympatry between both genotypic groups (i.e. G6/G7 and G8/G10). To date, none of the studies have demonstrated sympatry of all these four genotypes. Nevertheless, there are regions where at least some genotypes of these two genotypic groups are potentially sympatric. One such region is in north-eastern Europe, where G8 (this study) and G10 have been recorded from Latvia, and G7 in neighbouring Lithuania (Marcinkute et al., Reference Marcinkute2015). Considering that wolves (as a main definitive host species for G8/G10) can cover very long distances and their populations in Europe are connected over the distance of more than 800 km (Hindrikson et al., Reference Hindrikson2017), the possibility for gene flow between G7 and G8/G10 is potentially there, and yet the genotypic groups G6/G7 and G8/G10 are clearly separate on the nuclear phylogeny. Another region of potential sympatry is in eastern Russia, where G6 has been found in relative geographical proximity with G10 (>500 km between the reported cases) (Konyaev et al., Reference Konyaev2013; Yanagida et al., Reference Yanagida2017). Nevertheless, the phylogeny based on six nuclear loci (current study) shows also that gene flow between genotypic groups G6/G7 and G8/G10 has not been sufficient to merge all four genotypes into a single clade (species). A recent study by Yanagida et al. (Reference Yanagida2017) based on two nuclear loci (pepck and pold) indicated that some degree of gene flow might occur between G6/G7 and G8/G10 as they found few polymorphic sites where mutations were shared among G6/G7 and G8/G10. Based on this, they suggested that G6–G10 could be considered as one species. However, there were only a limited number of polymorphic characters in the two analysed loci, which may likely be the reason why their conclusion is not supported by the results of our study. One possible explanation for the shared characters reported in Yanagida et al. (Reference Yanagida2017) could be due to incomplete lineage sorting, which means that due to the relatively recent evolutionary divergence of G6/G7 and G8/G10, some loci have not had enough time to diverge and as a result there are still shared characters between different genotypes. This is actually evident also from our results. When we examined all six nuclear loci of our study (that include also pepck and pold used by Yanagida et al., Reference Yanagida2017), there are several positions in the alignment where the same nucleotide is shared between different genotypic groups. For example, in pepck all isolates of G8 and G10 have A in the shown position in Fig. 3, but remarkably A is also found in two isolates of G7. And yet, despite of some shared mutations between different genotypes, there are a large number of characters specific only either to the genotypic group G6/G7 or to G8/G10, and as a result in the phylogenetic tree the camel–pig genotypes G6/G7 firmly form one clade and the cervid genotypes G8/G10 another (Fig. 2). While we cannot rule out the possibility that to some extent gene flow (hybridization) between these two genotypic groups can occur, as suggested in Yanagida et al. (Reference Yanagida2017), the nDNA evidence in our study that is based on a larger number of nuclear loci compared with Yanagida and co-authors, clearly shows the phylogenetic division of G6–G10 into two clades, G6/G7 and G8/G10. According to the evolutionary (general lineage) species concept, these two clades can be regarded as distinct species as they represent two distinct evolutionary lineages and other data also support this (see below).

Fig. 3. Nucleotide position on pepck locus, where the same nucleotide A is shared between two samples of genotype G7 and the G8/G10 genotypic group. Depicted position according to FN567995 from the GenBank database is 236 (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp2011). Sample numbers correspond to sample numbers in Table 1.

Limited gene flow between species, i.e. hybridization, is in fact relatively common in nature. Possibly the most popular example is the hybridization between wolves and dogs (e.g. Hindrikson et al., Reference Hindrikson2012; Leonard et al., Reference Leonard and Gompper2014). In general, it has been estimated that 10–30% of multicellular animal and plant species hybridize regularly (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott2013). Hybridization is also well-known among parasites, it is known for example between different species of helminths (Taenia, Trichinella, Schistosoma, Fasciola, Ascaris) and protozoa (Plasmodium, Leishmania, Toxoplasma and Trypanosoma) (Arnold, Reference Arnold2004; Detwiler and Criscione, Reference Detwiler and Criscione2010; King et al., Reference King2015). Hybridization between closely related tapeworm species in Taeniidae has been demonstrated between T. saginata and T. asiatica (e.g. Okamoto et al., Reference Okamoto2010; Yamane et al., Reference Yamane2013). The occurrence of hybridization does not mean that two hybridizing species, if clearly separate on the phylogeny, should therefore be regarded as a single species, it just means that reproductive barrier between species has not yet fully developed.

Although our study did not include samples from the whole geographical range of the genotypes, we argue that this is not a major limitation, since our result shows that even in close geographical proximity these genotypic groups maintain their genetic differences. Moreover, our data included samples from north-eastern Europe where genotypes G7, G8 and G10 have been recorded in relatively close geographic areas. A need for including samples from the whole geographical range of the species would have been critical if the genetic data showed no differentiation on a smaller scale, but this was not the case here. Our results demonstrated that gene flow between G6/G7 and G8/G10 genotypic groups in relatively close geographical areas has been insufficient to merge them into a single clade, and instead they form two statistically well supported separate clades (species). One of the possible contributing factors for the limited gene flow between G6/G7 and G8/G10 could also be the reproduction mode of E. granulosus s. l. Although cross-fertilization can occur (e.g. Haag et al., Reference Haag2011), the main mode of reproduction appears to be self-fertilization (Lymbery, Reference Lymbery2017; Thompson, Reference Thompson2017). As the potential for outcrossing between genotypic groups is rare, the evolutionary potential for genetic differentiation and species divergence is high (Lymbery, Reference Lymbery2017).

Ecological, epidemiological and morphological differences of the two species

The division of G6–G10 into two separate species is also supported by other data that can be found in detail in Thompson (Reference Thompson2008) and Saarma et al. (Reference Saarma2009). Briefly, while G6/G7 is known to be typically circulating in the domestic cycle (camels, goats, pigs and dogs), G8/G10 cycles primarily in the sylvatic cycle, between cervids (moose, elk and reindeer) and wolves (Thompson and McManus, Reference Thompson and McManus2002; Lymbery, Reference Lymbery2017). Although G6 is commonly involved in a cycle between goats/camels–dogs and G7 mainly pigs–dogs, these two also share some overlap in their life cycles as both can infect the same intermediate hosts, such as goats and humans (Cardona and Carmena, Reference Cardona and Carmena2013; Alvarez Rojas et al., Reference Alvarez Rojas, Romig and Lightowlers2014; Addy et al., Reference Addy2017), and definitive host – dogs. Most likely dogs act as vectors for both genotypes, providing opportunities for outcrossing. Moreover, the geographical distribution of G6/G7 is largely different from G8/G10. G6 and G7 are sympatric in Turkey, Argentina and Peru (e.g. Moro et al., Reference Moro2009; Šnabel et al., Reference Šnabel2009; Soriano et al., Reference Soriano2010; Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Kaplan and Ozercan2011; Lymbery et al., Reference Lymbery2015). The recent discovery of the G6/G7 cluster in African wildlife is highly interesting on phylogeographical grounds and is currently further explored (Romig et al., Reference Romig2017). The cervid strains G8 and G10 are, in contrast, distributed in the northern part of Eurasia and North America (Lavikainen et al., Reference Lavikainen2003; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson2006; Moks et al., Reference Moks2008) and so far there are only a few recorded occurrences of G6 in northern latitudes (Konyaev et al., Reference Konyaev2013; Yanagida et al., Reference Yanagida2017). As G6/G7 circulate primarily in the domestic cycle and G8/G10 in the sylvatic cycle, the probability that parasites from different genotypic groups co-occur in the same definitive host and cross-fertilize is very low. On the other hand, since G6/G7 share the same final host (dog) cross-fertilization has apparently been frequent enough to guarantee that G6/G7 have not diverged. The same is valid for G8/G10, which utilize wild canids (mostly wolves) as definitive hosts. Thus, the association with distinct host species, largely separate geographical distribution and limited rate of cross-fertilization are the main factors that have limited the gene flow between genotypic groups G6/G7 and G8/G10. As a result, these genotypic groups can be regarded as distinct species.

Morphological comparisons of adult worms of G6/G7 and G8/G10 are scarce. Recently, it has been found that genotypes G6 and G7 share similar morphological characteristics, e.g. long terminal segment when compared with the total adult worm length, genital pore is generally anterior in the mature segment and rostellar hook morphometric data have also given similar results for both of these genotypes (Soriano et al., Reference Soriano2016). Based on the limited data, it has been suggested that there are some morphological differences in the reproductive anatomy between G6/G7 and G8/G10, and between rostellar hook morphology (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson2006; Lymbery et al., Reference Lymbery2015; Soriano et al., Reference Soriano2016). However, these differences need to be further confirmed as neither direct comprehensive morphological nor extensive ecological comparisons between G6/G7 and G8/G10 have been made so far. Such studies would provide additional valuable information for species delimitation.

Based on priority, the species name for G8/G10 should be E. canadensis; however, the species name for G6/G7 warrants further discussions. It has been proposed to use E. intermedius for G6/G7 (Thompson, Reference Thompson2008; Saarma et al., Reference Saarma2009); however, this name is highly problematic since the original description by Lopez-Neyra and Soler Planas (Reference Lopez-Neyra and Soler Planas1943) did not describe intermediate host and no original type specimen for E. intermedius can be found (Nakao et al., Reference Nakao, Lavikainen and Hoberg2015).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182018000719

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Antti Lavikainen and Tetsuya Yanagida for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by institutional research funding (IUT20-32) from the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (to U.S.); the Estonian Doctoral School of Ecology and Environmental Sciences (to T.L. and L.K.); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant Ro 3753/3-1 (to T.R.); the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme under the grant agreement 602051, Project HERACLES; http://www.Heracles-fp7.eu/ (to A.C.).

Declarations of interest

None.