As I sit down to write this issue’s NBC, Britain is still part of the European Union, although for how long and under what circumstances is something of a mystery, even to our current government. The EU has frequently been compared to an empire, both by its detractors and supporters, demonstrating the political capital we still invest in the term. This NBC will take a short trip into the archaeology of empires and borders, and discover that the issues of integration and migration currently concerning the EU have long histories. We will end with a detour into another pressing concern for many in the present, that of inequality. Here, too, the temporal scope available to archaeology means we have a lot to say.

Empires and edges

Bleda S. Düring & Tesse D. Stek (ed.). 2018. The archaeology of imperial landscapes. A comparative study of empires in the ancient Near East and Mediterranean world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 978-1-10718-970-6 £90.

Ulrike Matthies Green & Kirk E. Costion (ed.). 2018. Modeling cross-cultural interaction in ancient borderlands. Gainesville: University Press of Florida; 978-0-8130-5688-3 $84.95.

Our first volume examines empires across the Old World, and in places extends into South America. The archaeology of imperial landscapes emerged from a conference held in April 2014 at Leiden, led by a Near Eastern scholar (Düring) and a Romanist (Stek). In their Introduction, the two editors argue that the study of imperial-scale polities has been dominated by historians, and has consequently focused largely on the sorts of information easily derived from textual sources. We therefore have a relatively good understanding of many imperial bureaucracies, ideologies and elites, but a much more tenuous grasp of the impact of empire on societies as a whole. In particular, they aim to draw attention to changes occurring in rural landscapes and outside the core zones of imperial capitals. The approach taken is explicitly comparative. All empires “had to deal with similar logistical problems”—namely communication and the mobilisation of capital over long distances in a world where movement costs were high—meaning that “their solutions are often comparable” (p. 9). A key idea that emerges from the Introduction is that of “repertoires of rule”, defined as “the culturally developed toolkit for imperial control” (p. 10) available to imperial actors at any one moment. Although the concept is not applied throughout the book, I found it a useful one to engage with when reading each of the chapters.

After the Introduction, the volume is divided into three sections. The first of these discusses rural societies and landscapes, moving chronologically from the Assyrian Empires (Düring, Morandi Bonacossi) through the Achaemenids (Colburn) and Greeks (Attema), to the Romans (Stek). Düring shows how the Middle Assyrian Empire invested heavily in some parts of the landscape of northern Mesopotamia through major irrigation schemes and population movements, but elsewhere restricted itself to administration, extracting surplus but maintaining the agricultural status quo. The ability to be flexible in local responses while maintaining a clear imperial culture, manifested in a shared ceramic repertoire and strong provincial administration, gave the Middle Assyrians an edge over their rivals, enabling the empire to survive for several hundred years. Morandi Bonacossi uses data from his ongoing survey in Kurdistan to document the next stage of this empire, when the core area around imperial capitals such as Nineveh was transformed by massive investment in water systems of various kinds and by a huge increase in settlement, both urban and rural. A similar story occurred at the Kharga Oasis in Egypt during the Achaemenid period, with the introduction of qanat technology facilitating a boom in settlement, and allowing the region to be plugged into the developing imperial networks. Attema’s chapter on the chora of the Hellenistic city of Chersonesos in the Crimea is particularly interesting, and shows how the Greek settlers broadened their power base from a small city-state to a quasi-imperial entity by exploiting periodic crises in the grain trade. Detailed and systematic survey undertaken also reveals possible relationships with so-called Skythian nomads, over whom the inhabitants of Chersonesos exerted an even weaker level of control. In the final chapter of this section, Stek shows how Roman control of the Abruzzi mountains in Italy did not conform to standard models of ‘Romanisation’ of the landscape, which emphasise urban development, agricultural investment and land tenure changes such as centuriation. Instead, local and contingent processes played a role, especially with regard to the exploitation of pastoral and lacustrine resources, which were not traditionally discussed, even by writers at the time.

The second section moves from rural landscapes to peripheral ones. Ristvet discusses the relationship between the site of Oğlanqala, a fortified hilltop city in the Naxçivan region of modern day Azerbaijan, and the adjacent empire of Urartu. She finds evidence for deliberate resistance to Urartian power through the continued use of local monumental architecture styles, as well as an integration of Urartian practices such as the use of cuneiform script and participation in wider exchange networks. Boozer uses two case studies on the peripheries of Roman Egypt, the so-called Great Oasis and Nubia, to compare Roman imperial strategies. She argues that it is not possible to make a sharp distinction between the Roman presences in peripheral provinces, adjacent kingdoms or tribal areas on the basis of archaeological evidence, and in fact such distinctions may not have had any meaning for Romans and locals themselves. In the following chapter, de Jong and Palermo discuss the near-invisibility of Roman imperial control in northern Mesopotamia, a frontier region with the equally strong Parthian and later Sasanian empires. Finally, Vroom discusses the results of long-term excavations at the Albanian urban centre of Butrint. This site was occupied during the Byzantine period, and its fortunes can be tied to those of the empire as a whole, including the pivot to the West after defeats by Arab armies in the Near East during the seventh century and its eventual decline in the face of Arab, Norman and Lombard aggression in the eleventh century.

The final section includes three concluding chapters that take a broader comparative approach. Rogers discusses strategies of imperial expansion, identifying seven separate forms, and brings in several Inner Asian polities as comparators. Parker compares the Neo-Assyrian Empire with those of the Wari and Inca in the Andes. Despite the very different physical geography of the two regions, he explores similar approaches to settlement dispersal and infrastructure investment, as well as local diversity. In their conclusion, Stek and Düring make a cogent and valuable argument for large-scale comparative study of empires, and reiterate the contribution that only archaeology can make in this regard. Overall, this is an excellent volume. The case studies presented in the first two sections are full of new data and largely address the questions laid out in the Introduction. The final section draws out the theoretical implications of the ‘repertoires-of-rule’ approach, and ensures that the volume works as a coherent whole. Some may quibble that their preferred empire has been missed out, and the lack of a chapter on North Africa beyond Egypt is a little disappointing, but there can be little doubt that this is a significant contribution to imperial studies in archaeology.

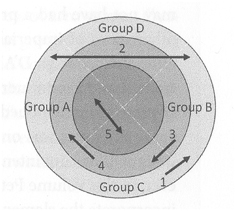

A perennial problem with the analysis of empires is one of visualisation. It is in the interests of the coloniser to present their control as absolute and defined, rather than as messy and contingent—consider the famous world maps produced by British cartographers in the Victorian era, with large swathes of the globe coloured a reassuring pink. Our second volume addresses this problem through a novel approach to depicting archaeological relationships. Modeling cross-cultural interaction in ancient borderlands provides a series of case studies examining the efficacy of the cross-cultural interaction model (CCIM) in different contexts. The CCIM is a graphic way of describing sets of relationships between social groups, based on the nature and degrees of interaction between them. It is essentially a theory composed of a diagram, and as such it is difficult to explain with only words, but I will have a go! Three concentric circles denote successive levels of interaction intensity, with the outermost representing limited cultural exchange (e.g. trade in prestige goods or raw materials), the middle selective cultural exchange (e.g. practices of material culture manufacture or food consumption) and the innermost intense cultural exchange (e.g. intermarriage, hybridisation). Finally, arrows denoting the direction of cultural exchange are superimposed onto the three concentric circles. These can be uni- or bidirectional, depending on the nature of the cultural exchange (e.g. one group adopting the material culture of another compared to two groups exchanging raw materials). The resulting depictions sound relatively simple, but in later chapters reach impressive levels of complexity.

After the brief Introduction, which helpfully points the reader to more detailed literature on the CCIM model, seven case-study chapters road test it as a method for depicting, but also thinking through, cultural exchange. Imperial polities feature heavily, and we start in the conventional borderland setting of the Roman-German frontier in the chapter by Peter Wells. In the first of many tweaks to the basic CCIM form, Wells adds a spatial dimension, showing how Roman material culture permeated beyond the fortified frontier zone along the Danube. Quantities of material culture diminish beyond about 75km from the ‘Roman’ world, although they are still present, until a second frontier is reached at sites over 300km away. Here, elites sought to position themselves as equals and alternatives to Rome, as can be seen by the emergence of runic script as a deliberate alternative to Latin. Feuer’s chapter examines the impact of the rise of the Mycenaean civilisation in central and southern Greece on highland Thessaly. By making CCIM diagrams for the Middle, Early Late and Late Bronze Ages, he is able to show how the coastal ports of Thessaly were far more integrated into the Mycenaean world than the upland zones, and that elites were much more involved than commoners. In Chapter 5, Tyson Smith and Buzon use a similar approach to show how the Nubian Kingdom of Kush was transformed by the imperial practices of New Kingdom Egypt, such that even when it regained its independence, Egyptian customs were retained. Costion and Green tackle the colonisation of the Moquegua Valley in Peru by the Wari and later Tiwanaku polities, showing how the integration of the valley into larger political units resulted in increased cultural connectivity, but also how some forms of exchange persisted through the waxing and waning of external political controls. Two of the chapters use the CCIM to examine relations within individual societies. Toft discusses exchange networks of European goods among Inuit cultures in Greenland during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Here we see the versatility of the model, as different coloured arrows are used to visualise an extremely complex set of relationships. Palumbo investigates the production and consumption of gold in pre-Hispanic Costa Rica and Panama, producing two diagrams for hypothetical situations of deflationary and inflationary pressure on the amounts of gold circulating within society. Interestingly, his results suggest that the deposition of gold objects in elite burials may indicate a decline in the absolute power of those same elites because it represents an attempt to take gold out of circulation and thereby raise the value of the remaining stock.

In their short conclusion to the volume, Green and Costion assess how successfully the CCIM was able to describe the many and varied social interactions documented by the case studies. As the designers of the original method, they have some skin in the game in this debate, but in general I agreed with their assessment that the model was useful for most of the case studies. Key to this, however, is its flexibility, and the ways in which it is modified by the authors to fit their particular circumstances. As several of the authors point out, the danger of the CCIM approach is that it may lead to simplistic depictions and descriptions, given that all of the nuanced possibilities covered by the term ‘interaction’ are reduced to single arrows. The detailed commentaries provided by the authors mitigate this, but raise the question of how useful the CCIM is in its own right. For me, the most successful uses were those that took a diachronic approach, producing multiple iterations of the diagram through time to compare the degree and types of interactions as social and political circumstances changed. We might contrast this with the less formalised approach adopted in the last section of The archaeology of imperial landscapes, where detailed contextual analysis allowed for the comparison of empires as diverse as the Mongols, Incas and Neo-Assyrians. Both approaches doubtless have contributions to make, but the large-scale comparative work seems to me a more fruitful line of enquiry.

How we were swindled and how long it has taken

Timothy A. Kohler & Michael E. Smith (ed.). 2018. Ten thousand years of inequality: the archaeology of wealth differences. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 978-0-8165-3774-7 $70.

Inequality has long been of significant concern across the social sciences, but since the Great Recession in the late 2000s, it has received unprecedented attention. Sociologists, historians, epidemiologists and economists have shown that although ‘more equal societies almost always do better’ across a range of health and social measures (Wilkinson & Pickett Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2009), the structural conditions of modern capitalist nation-state economies lead to increased wealth disparities among their populations through time (Piketty Reference Piketty2013). How did this situation arise, and are alternatives possible, or is increased inequality a necessary trade-off against increased social complexity? Archaeology is the only discipline capable of examining these questions before the emergence of writing, and therefore during the period when much social complexity emerged. One of the hallmarks of economic treatments of modern wealth inequalities is the use of large empirical datasets and descriptive statistics to produce quantitative measurements that can be independently compared. Of these, the most widely used is the Gini coefficient, a measure of the dispersal of values within a distribution often applied to household income in modern settings. Gini values normally range between 0 and 1, with 0 representing total equality, and 1 total inequality. In Ten thousand years of inequality, the authors explore how the Gini coefficient can be applied to the sorts of datasets available to archaeologists, and draw out some of the interpretive possibilities of such an approach.

The book begins with an excellent introductory chapter, laying out a history of the analysis of inequality in the past and pointing out the assumptions made along the way. Although the possibility of wealth inequality is linked to the production of surplus, as there is a greater amount of wealth to be distributed, a huge range of other factors complicate matters. Hunter-gatherer societies are not automatically more egalitarian than settled villages, or even early states and empires. Chapter 2, by Peterson and Drennan, provides a lucid and useful summary of statistical measures of inequality, pointing out some of the issues involved in using Gini coefficients on different kinds of archaeological data. In the absence of direct measures of income, they argue for the use of multiple strands of evidence, including household artefacts, house size and labour expended in manufacture. In the next chapter, Oka et al. produce a mathematical formula for combining and averaging Gini scores, and use it to investigate three case studies from a modern day refugee camp in Kenya via the medieval Indian Ocean to the Early Bronze Age Levant. At the Kakuma camp they discover a disparity between household consumption, measured by collecting a week’s worth of waste, and household size, perhaps because the latter was heavily regulated by the camp authorities. Prentiss et al., however, report similar findings in their comparison of house size with artefact and subsistence data from successive phases of the Bridge River site in British Columbia, suggesting households may be a relatively conservative measure of actual wealth differences. By contrast, Stone argues that for Mesopotamia, house size is a much more accurate measure of wealth than grave goods because the latter can reflect prestige as well as wealth, and also because the large number of graves recovered without associated material culture distorts the statistical validity of the Gini coefficient. Feinmann et al. find a fairly tight set of Gini values across a range of portable goods and house sizes in their study of the Oaxaca Basin.

Several chapters rely simply on house size data, but draw out interesting correlations with other datasets. Kohler and Ellyson examine the Pueblo Southwest from AD 600–1300, and make an intriguing correlation between increased inequality and evidence for violence, using trauma marks on human remains as a proxy for the latter. Pailes finds no evidence for inequality increasing in line with social complexity in the Hohokam region of the Southern USA, perhaps as a result of an inability to generate increased surplus as population increased. Bogaard et al. make an important distinction between living and storage space in households, and illustrate that access to storage is generally more unequal than living space. Combining these results with stable isotope results from Germany and northern Mesopotamia, they suggest that a combination of urbanisation and agricultural extensification contributed to greater inequality over time, but with contrasting levels of sustainability. The final chapter involves all the chapter authors and uses the household data to make comparisons between different social and cultural settings at a global scale. Here the power of the Gini coefficient approach comes into its own, as we can see clear patterns and broad trends. At this level, we can say that agricultural societies are more unequal than those of hunter-gatherers, with horticulturalists somewhere in between, and that towns and cities are more unequal than villages. An important difference emerges between societies in the Old and New Worlds, with the former attaining much higher levels of inequality. The authors suggest that the absence of traction animals in the New World meant that the societies there could not extensify production to the same extent as those in the Old World, resulting in smaller surpluses and lower overall inequality.

There are a range of issues with using Gini values to examine wealth inequality in the past, and several are raised by the authors themselves. One set of problems relates to the translation of the messy remains of past societies into simple values that can be inputted into the statistical models, especially in areas of the world that have not received significant archaeological attention. In these areas, sample sizes for evidence such as household area will be very small. From a theoretical perspective, there are issues in deciding which variables best serve as proxies for wealth, and these are borne out by some of the empirical work undertaken in the case studies. Combining multiple variables increases the interpretive power of using Gini values in local settings, as it is possible to identify and compare inequality in relation to different proxies such as house size, consumption practices and access to prestige goods, and to make statements about how these might interlink. This, however, reduces the scope for larger comparisons where methods need to be uniform. The emphasis on quantitative data also risks missing forms of inequality that do not have direct and durable material results. All of this being said, this volume represents a significant advance in archaeological scholarship. It demonstrates how, by producing statistically robust and methodologically clear arguments, archaeology will be able to contribute to one of the most pressing challenges we face. The Gini coefficient for the modern USA is 0.85. The highest reached in the datasets used in the book was 0.65, attained by the Iron Age centre of the Heuneberg in Germany. As the authors point out, the latter only lasted some 200 years.