‘Theory of mind' and ‘mentalising’ refer to the cognitive ability to attribute mental states such as thoughts, beliefs and intentions to people, allowing an individual to explain, manipulate and predict behaviour. In 1992 Frith proposed a relationship between theory of mind and schizophrenia, and argued that several symptoms of schizophrenia could be explained by mentalising impairment (Reference FrithFrith, 1992). This led to a substantial body of research which has recently been critically reviewed twice (Reference BrüneBrüne, 2005a ; Reference Harrington, Siegert and McClureHarrington et al, 2005a ). In both reviews it was concluded that theory of mind is impaired in individuals with schizophrenia. Although these reviews were executed thoroughly, they are limited to a qualitative description of the observed deficit, thus lacking important information on the magnitude of the effect. The purpose of this meta-analysis is to produce a synthesised effect size estimate that has considerably more power than the individual studies. In addition, effects of study characteristics on the findings are analysed.

METHOD

Study selection

An extensive literature search was conducted in the electronic databases Medline, EMBASE and PsycINFO (January 1993 to May 2006) using the following key words: theory of mind, mentalizing, social cognition, schizophrenia, and psychosis. Additional studies were identified by checking the reference lists from identified reviews and papers on the topic. To ensure that we did not overlook studies published by May 2006 but not included in the computerised databases by that date, a journal-by-journal search was performed in the January 2006 to May 2006 editions of the American Journal of Psychiatry, Biological Psychiatry, Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Psychiatry Research, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Schizophrenia Research and Psychological Medicine. Studies considered eligible for this meta-analysis were empirical research studies written in the English language and published in peer-reviewed journals. Research samples had to be composed of adults diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to the established diagnostic systems (DSM or ICD). Their sample group's mentalising performance had to be compared with that of healthy controls. Measures of mentalising included in this meta-analysis are described below. Finally, sufficient data had to be reported for the computation of the standardised mean difference (Reference Lipsey and WilsonLipsey & Wilson, 2001).

Types of mentalising tasks

There is a fair amount of agreement on the definition of theory of mind among researchers. However, this definition is broad, perhaps reflecting the fact that it is probably not a unitary function. This has led to a wide variation in the operationalisation of the concept. One of the most frequently used types of mentalising tasks is the false belief or deception task (e.g. Reference Frith and CorcoranFrith & Corcoran, 1996; Reference Corcoran, Cahill and FrithCorcoran et al, 1997; Reference Doody, Gotz and JohnstoneDoody et al, 1998; Reference Mazza, De Risio and SurianMazza et al, 2001). In a first-order false belief/deception task, the ability to understand that someone can hold a belief that is different from the actual state of affairs is assessed. In a second-order false belief/deception task, participants have to infer the (false) beliefs of one character about the (false) beliefs of a second character.

A second type of theory of mind task commonly used in schizophrenia research is an intention-inferencing task, in which the ability to infer a character's intentions from information in a short story is assessed (e.g. Sarfati et al, Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Besehe1997a ,Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Nadel b , Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Brunet1999, Reference Sarfati, Passerieux and Hardy-Baylé2000; Reference Sarfati and Hardy-BayleSarfati & Hardy-Baylé, 1999). A third type of task measures the ability to understand indirect speech, such as in irony, banter, hints and metaphors (e.g. Reference Corcoran, Mercer and FrithCorcoran et al, 1995; Langdon et al, 2002; Reference CorcoranCorcoran, 2003; Reference Corcoran and FrithCorcoran & Frith, 2003; Reference Craig, Hatton and CraigCraig et al, 2004). This is based on the notion that for the understanding of indirect speech an understanding of another person's mental state is required (e.g. Reference Sperber and WilsonSperber & Wilson, 2002). However, Langdon & Coltheart (Reference Langdon and Coltheart2004) showed that comprehension of irony and comprehension of metaphors are unrelated and that having an intact theory of mind is a prerequisite for the interpretation of irony but not for the interpretation of metaphors. Therefore, data on the interpretation of metaphors were excluded from this meta-analysis.

A fourth, less commonly used type of theory of mind task in schizophrenia research is the attribution of mental states to animated geometric shapes which interact in a ‘socially’ complex way (Reference Blakemore, Sarfati and BazinBlakemore et al, 2003; Reference Russell, Reynaud and HerbaRussell et al, 2006). This type of task may not be fully comparable with the other theory of mind tasks because of the higher level of abstraction involved. Finally, in some studies the ‘eyes’ task is used, in which participants have to infer mental states from looking at pictures of eyes (Reference Kington, Jones and WattKington et al, 2000; Reference Russell, Rubia and BullmoreRussell et al, 2000; Reference Kelemen, Erdelyi and PatakiKelemen et al, 2005). This has been referred to as a theory of mind task, but at face value the construct being measured seems to be different from that assessed by the other paradigms, perhaps assessing emotion recognition abilities or empathy rather than theory of mind.

Since there is a serious lack of research on the psychometric properties (including construct validity and criterion validity) of the many different theory of mind tasks that have been developed (Reference Harrington, Siegert and McClureHarrington et al, 2005a ), it may not be possible to formulate completely objective inclusion criteria regarding the type of tasks used in the studies. In this meta-analysis this problem is addressed statistically in two ways. First, homogeneity analyses are used to check whether the grouping of effect sizes from different studies shows more variation than would be expected from sampling error alone, indicating that the effect sizes may not be comparable. A second approach to this problem is to break down the overall mean effect size into mean effect sizes for different types of tasks. For these mean effect sizes per type of task to be meaningful, we (subjectively) set a minimum of five eligible studies per sub-task analysis. This led to the exclusion of two studies using tasks assessing the attribution of mental states to abstract shapes rather than humans (Reference Blakemore, Sarfati and BazinBlakemore et al, 2003; Reference Russell, Reynaud and HerbaRussell et al, 2006), and three studies in which the ‘eyes’ task was used (Reference Kington, Jones and WattKington et al, 2000; Reference Russell, Rubia and BullmoreRussell et al, 2000; Reference Kelemen, Erdelyi and PatakiKelemen et al, 2005).

Schizophrenia subgrouping

Ever since Frith's first proposal (Reference FrithFrith, 1992), the association between mentalising and the core symptoms of schizophrenia has been an important focus of research interest. Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder and various subgrouping methods have been used, based on different theories regarding the relationship between mentalising and symptomatology.

In earlier studies, Frith and colleagues divided their schizophrenia samples into six symptom subgroups (Reference Corcoran, Mercer and FrithCorcoran et al, 1995). In their later studies, the number of subgroups was reduced to four, categorised as follows:

-

(a) behavioural signs of negative symptoms and/or incoherence;

-

(b) paranoid symptoms (delusions of persecution, delusions of reference, and third-person hallucinations);

-

(c) passivity experiences (delusions of control, thought insertion, and thought broadcasting);

-

(d) symptoms in remission.

The first group was predicted to be the most impaired, because of these patients' incapacity to represent the mental states of others as well as themselves. Paranoid patients would perform poorly because of their difficulties in monitoring other people's intentions. Patients whose symptoms were in remission and patients with passivity symptoms were predicted to have normal mentalizing abilities. These hypotheses were largely confirmed and have repeatedly been replicated (Reference Frith and CorcoranFrith & Corcoran, 1996; Reference Corcoran, Cahill and FrithCorcoran et al, 1997; Reference Pickup and FrithPickup & Frith, 2001).

Sarfati and colleagues (Sarfati et al, Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Besehe1997a ,Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Nadel b , Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Brunet1999; Reference Sarfati and Hardy-BayleSarfati & Hardy-Baylé, 1999) and Zalla et al (Reference Zalla, Bouchilloux and Labruyere2006) suggested that impairment of theory of mind is related to thought disorder, reflecting an executive functioning deficit. Thus, their samples were divided into those with and those without thought disorder. In all of their studies thought-disordered participants performed significantly more poorly than healthy controls. However, in two of the studies the non-disorganised participants also showed poor performance (Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and NadelSarfati et al, 1997b ; Reference Zalla, Bouchilloux and LabruyereZalla et al, 2006).

Three research groups studied the relationship between mentalising and paranoid delusions (Reference Randall, Corcoran and DayRandall et al, 2003; Reference Craig, Hatton and CraigCraig et al, 2004; Reference Harrington, Langdon and SiegertHarrington et al, 2005b ). In all three studies patients with paranoid delusions showed impairment of theory of mind relative to the normal control group. However, in the study by Randall et al (Reference Randall, Corcoran and Day2003), theory of mind performances of the paranoid and non-paranoid subgroups did not differ significantly from each other. Lastly, Herold et al (Reference Herold, Tenyi and Lenard2002) investigated whether the deficit in theory of mind was state- or trait-dependent and therefore assessed patients whose schizophrenia was in remission. Results showed that theory of mind impairment was still present in the remission phase of the illness.

Moderator variables

Published research suggests a number of variables that may affect mentalising performance and thus influence effect size. Hence, we aimed to code these variables in order to evaluate their influence on the effect size. Potential moderator variables at individual patient level are age, gender, medication, IQ, disease status (acute, chronic or in remission), severity of psychopathology, and symptoms. To analyse the effect of specific clusters of symptoms on mentalising impairment, the symptom subgroups used by different research groups were divided into four categories:

-

(a) symptoms of disorganisation;

-

(b) no symptoms of disorganisation;

-

(c) paranoid symptoms;

-

(d) remitted patients.

The disorganised subgroup was composed of the behavioural symptoms subgroup of the studies by Frith and colleagues (Corcoran et al, Reference Corcoran, Mercer and Frith1995, Reference Corcoran, Cahill and Frith1997; Reference Pickup and FrithPickup & Frith, 2001) and the disorganised subgroups of the Sarfati, Mazza and Zalla studies (Sarfati et al, Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Besehe1997a ,Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Nadel b , Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Brunet1999; Reference Sarfati and Hardy-BayleSarfati & Hardy-Baylé, 1999; Reference Mazza, De Risio and SurianMazza et al, 2001; Reference Zalla, Bouchilloux and LabruyereZalla et al, 2006). The non-disorganised patients of the Sarfati and Zalla studies were combined into the second subgroup (Sarfati et al, Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Besehe1997a ,Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Nadel b , Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Brunet1999; Reference Sarfati and Hardy-BayleSarfati & Hardy-Baylé, 1999; Reference Zalla, Bouchilloux and LabruyereZalla et al, 2006). For the paranoid subgroup the results of the studies focusing on paranoid schizophrenia (Reference Randall, Corcoran and DayRandall et al, 2003; Reference Craig, Hatton and CraigCraig et al, 2004; Reference Harrington, Langdon and SiegertHarrington et al, 2005b ) were combined with the results for the paranoid subgroups of the studies by Frith and colleagues (Corcoran et al, Reference Corcoran, Mercer and Frith1995, Reference Corcoran, Cahill and Frith1997; Reference Pickup and FrithPickup & Frith, 2001). The remitted disease subgroup comprised the patients in remission in the studies by Herold et al (Reference Herold, Tenyi and Lenard2002), Randall et al (Reference Randall, Corcoran and Day2003) and Frith and colleagues (Reference Corcoran, Mercer and FrithCorcoran et al, 1995; Reference Corcoran, Cahill and FrithCorcoran et al, 1997; Reference Pickup and FrithPickup & Frith, 2001). The passivity subgroup of Frith and colleagues was not coded, because results for that subgroup were reported only in two studies.

Potential moderators at study level are the matching of patients and controls on group characteristics (e.g. mean age, mean IQ, gender distribution), type of mentalising task used, and whether the task is administered verbally or non-verbally. Four types of theory of mind tasks were distinguished: first-order false belief/deception; second-order false belief/deception; intention inferencing; and comprehension of indirect speech. Some tasks did not fit in any of these categories, for example the false belief/deception tasks for which the orders were unknown or mixed.

Within the different task paradigms there is also variation in whether tasks are presented in a verbal or non-verbal form. It has been suggested that verbalisation may be impoverished in schizophrenia and may constitute an experimental bias in favour of a theory of mind deficit in people with schizophrenia (e.g. Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and BrunetSarfati et al, 1999). In a separate coding, tasks were classified as verbal or non-verbal.

Coding

Each study was coded independently by two authors (M.S. and E.V.). In case of discrepancies, consensus was reached in conference with the whole research group. When results were reported in graphical form only an email was sent to the author with a request for the exact numerical results.

Data collection and analysis

For each study an unbiased standardised mean difference (d), was calculated using reported means and standard deviations. This effect size statistic is computed as the difference between the mean of the schizophrenia group and the mean of the control group, divided by the pooled standard deviation. Hedges' formula was applied to correct for upwardly biased estimation of the effect size in small samples (Reference Lipsey and WilsonLipsey & Wilson, 2001).

When means and standard deviations were not available, d was calculated from the reported t or F values. In cases where the only reported outcome variable was the proportion of participants with a good (or poor) performance, d was estimated using the probit transformation method (Reference Lipsey and WilsonLipsey & Wilson, 2001). A sensitivity analysis was performed to check whether there was any significant effect of using probit-transformed effect sizes on the overall effect size. In studies in which data were reported for (symptom) subgroups only, data were first pooled and then compared as one group with the control group. In addition, the effect sizes of symptom subgroups were calculated for subsequent analyses. Several studies used more than one (sub)task to assess theory of mind, and therefore had more than one effect size; in these cases a pooled effect size was computed. However, if the authors had included a composite score, the effect size of this score was calculated. Again, effect sizes for different task types were calculated for subsequent analyses. In addition to the individual effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals, P values were calculated for each study using two-tailed independent t-tests and χ2-tests.

The mean effect size across studies was calculated by weighting each effect size by the inverse of its sampling variance. A confidence interval and z-value were calculated to examine the statistical significance of the effect. To test whether the individual effect sizes are good estimators of the population effect size, the homogeneity statistic Q was calculated (Reference Lipsey and WilsonLipsey & Wilson, 2001). Because sample sizes are small in the subgroup and task type analyses (see below), a random effects model was fitted to the data (Reference Lipsey and WilsonLipsey & Wilson, 2001). To examine publication bias, a fail-safe number was computed using Orwin's formula (Reference Lipsey and WilsonLipsey & Wilson, 2001). This indicates the number of studies with null effects that have to reside in file drawers to reduce the mean effect size to a negligible level (which we set at 0.2). Weighted regression analysis was performed using the statistical package Meta-Stat (Reference Rudner, Glass and EvarttRudner et al, 2002) to evaluate whether group differences in IQ, gender and age had an impact on effect size. Other variables with a potential influence on effect size, such as patient status, medication use and severity of psychopathology, could not be analysed because of the small number of studies reporting results for these parameters. Separate analyses were performed to analyse whether mentalising impairment is different for different symptom subgroups or for different types of mentalising tasks.

RESULTS

The literature search resulted in a total of 32 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. One publication (Reference Langdon, Davies and ColtheartLangdon et al, 2002a ) was excluded because data concerning the same participants had been reported in another paper (Reference Langdon, Coltheart and WardLangdon et al, 2002b ). Sample characteristics (n, mean age, percentage of males, mean score on the Binois–Pichot Vocabulary Scale and mean score on the non-verbal theory of mind test) were exactly the same in two studies by Sarfati and colleagues (Reference Sarfati and Hardy-BayleSarfati & Hardy-Baylé, 1999; Reference Sarfati, Passerieux and Hardy-BayléSarfati et al, 2000), suggesting that the same patient samples had been used. Because in the first of these studies the patient sample was divided into symptom subgroups, but more control participants and an additional theory of mind task were used in the latter study, instead of selecting one of the two studies the results of both were combined. Because we were unable to contact the authors of one study within the time frame of data collection and data analysis to obtain the exact numerical results which were not reported in the article, the results of that study could not be included in the meta-analysis (Reference Frith and CorcoranFrith & Corcoran, 1996). The characteristics of the remaining 29 studies with a total of 831 patients (mean age 35.9 years, 70% male, mean IQ 98.7) and 687 controls (mean age 35.2 years, 60% male, mean IQ 105.3) are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Schizophrenia/control sample | Schizophrenia subgroups | Mentalising tasks | P 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean age (years) | Males (%) | Mean IQ 1 | |||||||

| Corcoran et al (Reference Corcoran, Mercer and Frith1995) | 55/30 | 32/31 | 69/67 | 98/107 | Negative, incoherent, paranoid, passivity, other, remission | Hinting task; 10 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Sarfati et al (Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Besehe1997a ) | 24/24 | 32/32 | 79/58 | NR | With and without disorganisation | Intention-inferencing; 28 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Sarfati et al (Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Nadel1997b ) | 12/12 | 27/26 | 42/50 | NR | No subgroups | False belief task; 15 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Intention-inferencing; 15 picture stories | <0.005 | |||||||||

| Corcoran et al (Reference Corcoran, Cahill and Frith1997) | 44/40 | 30/32 | 71/43 | 102/108 | Behavioural, paranoid, passivity, remission | First-order false belief; 10 verbal/picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Langdon et al (Reference Langdon, Michie and Ward1997) | 20/20 | 33/NR | 45/NR | NR | No subgroups | Pretence; 3 picture stories | <0.025 | |||

| Unrealised goal; 3 picture stories | <0.05 | |||||||||

| Intention-inferencing; 3 picture stories | <0.05 | |||||||||

| First-order false belief; 3 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||||||||

| Doody et al (Reference Doody, Gotz and Johnstone1998) | 28/20 | 46/20 | 61/45 | 108/109 | No subgroups | First-order false belief; 1 verbal story | 0.5 | |||

| Second-order false belief; 1 verbal story | <0.005 | |||||||||

| Sarfati et al (Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Brunet1999) | 26/13 | 32/33 | 81/85 | NR | With and without disorganisation | Intention-inferencing; 28 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Intention-inferencing; 28 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||||||||

| Sarfati & Hardy-Baylé (Reference Sarfati and Hardy-Bayle1999), combined with Sarfati et al (Reference Sarfati, Passerieux and Hardy-Baylé2000) | 25/25 | 33/NR | 28/NR | NR | With and without disorganisation | Intention-inferencing; 14 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Mazza et al (Reference Mazza, De Risio and Surian2001) | 35/17 | 34/37 | 89/86 | 88/90 | No subgroups | First-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Second-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | <0.00005 | |||||||||

| Pickup & Frith (Reference Pickup and Frith2001) | 40/35 | 39/43 | 73/54 | 93/103 | Behavioural, paranoid, passivity, remission | First-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | 0.5 | |||

| Second-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | <0.005 | |||||||||

| Langdon & Coltheart (Reference Langdon and Coltheart2001) | 32/24 | 37/35 | 56/50 | NR | No subgroups | False belief; 4 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Langdon et al (Reference Langdon, Coltheart and Ward2002b ) | 25/20 | NR | NR | NR | No subgroups | False belief; 4 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Hinting task; 10 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||||||||

| Herold et al (Reference Herold, Tenyi and Lenard2002) | 20/20 | NR | NR | NR | Paranoid in remission | First-order false belief; 1 verbal story | >0.05 | |||

| Second-order false belief; 1 verbal story | >0.05 | |||||||||

| Irony task; 2 verbal stories | <0.005 | |||||||||

| Janssen et al (Reference Janssen, Krabbendam and Jolles2003) | 43/43 | 32/35 | 56/51 | 105/113 | No subgroups | First-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | >0.05 | |||

| Hinting task; 10 verbal stories | <0.005 | |||||||||

| Corcoran & Frith (Reference Corcoran and Frith2003) | 59/44 | 41/40 | 85/80 | 101/103 | No subgroups | Hinting task; 10 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||

| False belief; 4 verbal/picture stories | <0.0005 | |||||||||

| Brunet et al (Reference Brunet, Sarfati and Hardy-Baylé2003a ) | 7/8 | 31/23 | 100/100 | 111/119 | No subgroups | Intention-inferencing; 18 picture stories | <0.025 | |||

| Brunet et al (Reference Brunet, Sarfati and Hardy-Baylé2003b ) | 25/25 | 31/34 | 76/68 | NR | No subgroups | Intention-inferencing; 14 picture stories | <0.005 | |||

| Mazza et al (Reference Mazza, De Risio and Tozzini2003) | 39/20 | 43/43 | 83/65 | 87/86 | Positive and negative | First-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Second-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||||||||

| Brüne (Reference Brüne2003) | 23/12 | 29/30 | 74/58 | 92/107 | No subgroups | First-order false belief; 1 picture story | >0.05 | |||

| Second-order false belief; 1 picture story | <0.05 | |||||||||

| False belief; 1 picture story | >0.05 | |||||||||

| Corcoran (Reference Corcoran2003) | 39/44 | 41/40 | 82/80 | 103/104 | No subgroups | Hinting; 10 verbal stories | <0.005 | |||

| Randall et al (Reference Randall, Corcoran and Day2003) | 32/18 | 35/32 | 69/61 | 110/115 | Paranoid and paranoid in remission | First-order false belief; 3 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Second-order false belief; 3 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||||||||

| Craig et al (Reference Craig, Hatton and Craig2004) | 16/16 | 32/29 | 69/69 | 105/110 | Paranoid only | Hinting; 10 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Marjoram et al (Reference Marjoram, Tansley and Miller2005a ) | 20/20 | 40/40 | 60/55 | 97/100 | No subgroups | False belief; 31 verbal/picture stories | <0.005 | |||

| Marjoram et al (Reference Marjoram, Gardner and Burns2005b ) | 15/15 | 28/34 | 87/67 | 97/106 | No subgroups | Hinting; 10 verbal stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Brüne & Bodenstein (Reference Brüne and Bodenstein2005) | 31/21 | 39/34 | 74/48 | 100/105 | No subgroups | False belief, mixed orders; 6 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| ToM questionnaire; 23 questions | <0.0005 | |||||||||

| Brüne (Reference Brüne2005b ) | 23/18 | 39/36 | 78/44 | 100/105 | No subgroups | False belief, mixed orders; 6 picture stories | <0.001 | |||

| ToM questionnaire; 23 questions | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Harrington et al (Reference Harrington, Langdon and Siegert2005b ) | 25/38 | 34/36 | NR | 101/106 | Paranoid and not paranoid | First-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | <0.05 | |||

| Second-order false belief; 2 verbal stories | <0.001 | |||||||||

| False belief; 4 picture stories | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Zalla et al (Reference Zalla, Bouchilloux and Labruyere2006) | 38/40 | 41/41 | 53/53 | 91/104 | With and without disorganisation | First-order false belief; 8 picture stories | <0.0005 | |||

| Langdon et al (Reference Langdon, Coltheart and Ward2006) | 22/18 | 41/36 | 55/50 | 104/110 | No subgroups | False belief; 4 picture stories | <0.005 | |||

NR, not reported; ToM, theory of mind

1. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

2. Significance level of the difference in performance between the patients and the controls

Analysis of the total sample

Figure 1 shows the 29 individual effect sizes with their 95% confidence intervals. None of the confidence intervals includes the value zero, indicating a statistically significant effect for each study. The weighted mean effect size of the combined sample is –1.255 (95% CI –1.441 to –1.069) which is also statistically significant (z=13.25, P<0.0001). Homogeneity analysis showed that there was homogeneity among studies (Q=29.13, d.f.=28, P<0.41), and weighted regression analysis did not show any relationship between effect size and difference between patient and control groups in IQ (P=0.193), proportion of males (P=0.115) and age (P=0.147). The fail-safe number was 153, which indicates that 153 unpublished studies are required to reduce the effect size of the combined findings to a negligible level.

Fig. 1 Individual and mean effect sizes (d) and 95% confidence intervals of mentalising deficits in schizophrenia.

Analyses of the symptom subgroups

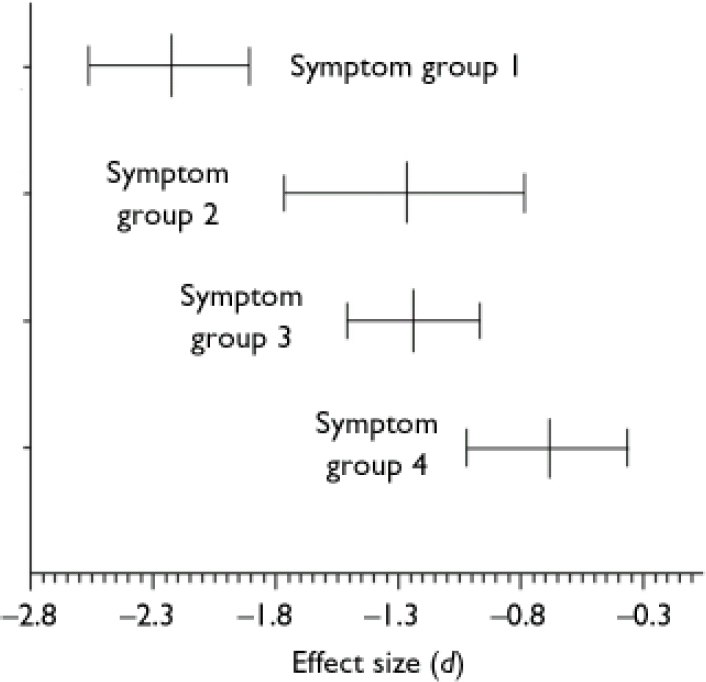

Mean effect sizes and confidence intervals of the symptom subgroups are displayed in Fig. 2. The disorganised patients performed worst on the mentalising tasks compared with healthy controls (d=–2.231, 95% CI –2.565 to –1.897, P<0.01). The confidence interval of the mean effect size in the disorganized subgroup shows no overlap with that in the non-disorganised (d=–1.278, 95% CI –1.771 to –0.785, P<0.01) and paranoid subgroups (d=–1.241, 95% CI –1.514 to –0.968, P<0.01), indicating that the difference between the disorganised subgroup and the other subgroups is statistically significant. This was confirmed by post hoc comparisons of the mean effect size of the disorganised subgroup v. the mean effect sizes of the other three symptom subgroups (all P values <0.01). Interestingly, patients in remission also showed a significantly worse performance than controls (d=<0.692, 95% CI –1.017 to –0.367, P<0.01). The homogeneity statistic of the non-disorganised subgroup was statistically significant (Q=7.3816, d.f.=4, P<0.05), indicating that the effect sizes within this subgroup analysis differed more than would be expected from sampling error alone, perhaps owing to differences associated with study (or sample) characteristics. This was somewhat surprising, since four of the five studies were by the same research group. The finding that the other three homogeneity statistics were not statistically significant suggests that although different authors might have used different criteria for their symptom subgroups, combining these subgroups was meaningful.

Fig. 2 Mean effect sizes (d) and 95% confidence intervals of mentalising deficits in symptom subgroups of schizophrenia: group 1, with disorganisation (n=9); group 2, without disorganisation (n=5); group 3, paranoid (n=6); group 4, remission (n=5).

Analyses of the types of mentalising tasks

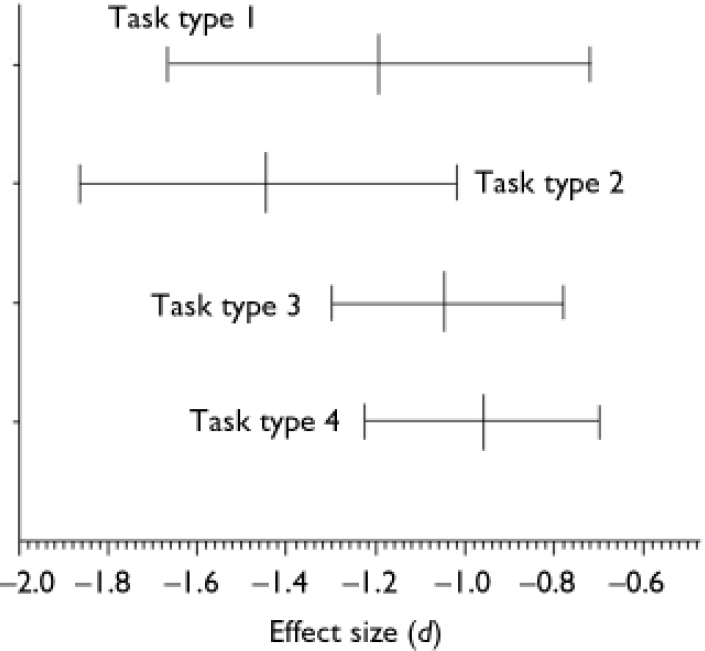

The mean effect sizes and confidence intervals of the four theory of mind task categories are shown in Fig. 3. The mean effect sizes of the first-order tasks (d=–1.193, 95% CI –1.666 to –0.720, P<0.01) and the second-order tasks (d=–1.443, 95% CI –1.867 to –1.019, P<0.01) have homogeneity statistics indicating heterogeneity among the effect sizes: Q=97.691, d.f.=12 (P<0.01) and Q=17.875, d.f.=6 (P<0.01) respectively. In contrast, the mean effect sizes within both the indirect speech tasks (d=<1.040, 95% CI –1.301 to –0.779, P<0.01) and the intention-inferencing tasks (d=–0.959, 95% CI –1.228 to –0.690, P<0.01) are both homogeneous. The difference between the mean effect sizes for different subtasks could not be analysed statistically, because not all effect sizes were statistically independent since in one study different types of tasks might have been used.

Fig. 3 Mean effect sizes (d) and 95% confidence intervals of mentalising deficits for different types of mentalising tasks: 1, first-order false belief and deception tasks (n=13); 2, second-order false belief and deception tasks (n=7); 3, tasks assessing the comprehension of indirect speech (n=8); 4, intention-inferencing tasks (n=7).

The mean effect size of studies using verbal tasks is comparable with the mean effect size of studies using non-verbal tasks (verbal, d=–1.221, 95% CI –1.462 to –0.980; non-verbal d=–1.251, 95% CI –1.496 to –1.006). The homogeneity statistics of the verbal and non-verbal tasks both show heterogeneity among the effect sizes. Again, the difference could not be analysed because of statistical dependence.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this meta-analysis was to investigate the extent of mentalising impairment in people with schizophrenia. By combining 29 studies, a total sample size was created of over 1500 participants. The overall effect size was –1.1255, indicating that on average the theory of mind performance of participants with schizophrenia is more than one standard deviation below that of healthy controls. According to a widely used convention for appraising the magnitude of effect sizes this is considered a large effect (Reference CohenCohen, 1988). Homogeneity analysis showed that the mean effect size of the combined samples is a good estimate of the typical effect size in the population. The large fail-safe number makes the ‘file drawer’ problem, which is a limitation of some meta-analyses, negligible.

The moderator variables IQ, gender and age did not significantly affect mean effect size. Thus, the impairment in theory of mind is robust and is not readily moderated by variables that may seem relevant. However, the effect of other potentially important moderator variables such as medication use and duration and severity of illness could not be analysed owing to a lack of information on these characteristics in many studies.

Participants with schizophrenia who had signs and symptoms of disorganisation were found to be significantly more impaired in terms of theory of mind than those in the other symptom subgroups. However, these results may also be explained by the composition of the disorganised symptom subgroup. The behavioural subgroup of the studies by Frith and colleagues was ranked highest in their hierarchical model. Thus, individuals in this group might also have had symptoms of the paranoid and/or passivity subgroup. This brings the risk that poorer performance in this group may be explained by having more severe and complex symptoms (Reference Harrington, Siegert and McClureHarrington et al, 2005a ). Similarly, in two of the four studies by Sarfati and colleagues the disorganised subgroup had more general psychopathology, which might explain their poorer theory of mind performance (Reference Sarfati and Hardy-BayleSarfati & Hardy-Baylé, 1999; Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and BrunetSarfati et al, 1999).

The mean effect size (d=–0.692) of mentalising impairment in patients in remission was smaller than in the other symptom subgroups, but is still considered to be medium to large (Reference CohenCohen, 1988). Moreover, this effect did not differ significantly from the effect sizes of the disorganised and paranoid subgroups.

Unexpectedly – and despite apparent differences in type and difficulty of the theory of mind tasks – the mean effect sizes for different task types were found to be similar. An explanation might be that our method of grouping studies by task types was not correct. This is supported by the finding that two of the four task type analyses showed heterogeneity among effect sizes. However, since there is a lack of research on the psychometric properties of the tasks that were used, such as construct and concurrent validity, it is not yet possible to categorise these tasks objectively.

There was also no difference between the mean effect sizes of verbal and non-verbal tasks, which is consistent with the findings of Sarfati and colleagues (Sarfati et al, Reference Sarfati, Hardy-Bayle and Brunet1999, Reference Sarfati, Passerieux and Hardy-Baylé2000). Thus, impairment of theory of mind does not to appear to be affected by verbalisation deficits that have been reported in people with schizophrenia.

Mentalising in schizophrenia: generalised v. specific impairment

As shown by Heinrichs & Zakzanis (Reference Heinrichs and Zakzanis1998), people with schizophrenia show generalised neurocognitive impairment. On their list of 22 mean effect sizes of common neurocognitive tests, the effect size of mentalising impairment would be ranked fourth. An interesting question is whether poor mentalising performance in schizophrenia interacts with or is influenced by general cognitive impairment. This problem is acknowledged by some authors, who corrected for general cognitive abilities by matching groups on IQ, covarying out cognitive variables (e.g. attention, executive functioning, memory, general picture sequencing abilities) or excluding participants from statistical analyses if they answered reality questions about the theory of mind stories incorrectly. In their reviews, Brüne ne (Reference Brüne2005a : p. 25, Table 1) and Harrington et al (Reference Harrington, Siegert and McClure2005a : pp. 252–267, Table 1) discussed the empirical evidence as to whether the mentalising deficits in schizophrenia are specific or the consequence of general cognitive impairment. In both reviews it was concluded that the evidence speaks in favour of the notion that there is a specific theory of mind deficit in schizophrenia. As with many neurocognitive tests, theory of mind tasks probably measure several component processes at the same time. For example, tasks in which the comprehension of indirect speech is assessed may require not only mentalising abilities but also basic language comprehension and expressive language skills. Possibly, general cognitive abilities represent a necessary but not sufficient condition for adequate mentalising, which is known as the ‘building block’ view of social cognition (see Reference Penn, Corrigan and BentallPenn et al, 1997).

Mentalising in schizophrenia: state or trait dependency

In his cognitive model of the relationship between meta-representation and the signs and symptoms of schizophrenia, Frith assumed that in people with this disorder, the initial development of mentalising abilities is relatively normal and that these abilities become impaired as the illness develops (Reference FrithFrith, 1992). In the subsequent studies by him and his colleagues, it was predicted and found that patients who were in remission (i.e. symptom-free) were unimpaired compared with normal controls (e.g. Corcoran et al, Reference Corcoran, Mercer and Frith1995, Reference Corcoran, Cahill and Frith1997; Reference Frith and CorcoranFrith & Corcoran, 1996; Reference Pickup and FrithPickup & Frith, 2001). In contrast, our meta-analysis has shown that patients have significant impairment during remission, which is consistent with the findings of Herold et al (Reference Herold, Tenyi and Lenard2002). These findings support the notion that mentalising is not just a consequence of the acute phase of the disorder but may be trait-dependent. It cannot be excluded that the criteria for remission (e.g. partial or full remission) used by Herold et al (Reference Herold, Tenyi and Lenard2002) and by Frith and colleagues are different. Other factors such as (prophylactic) treatment may also explain the divergent findings. However, more support for the trait argument comes from studies on mentalising in populations at elevated risk of developing a psychotic illness.

In general, people at genetic risk of schizophrenia show reduced performance on the more common types of theory of mind tasks (Reference Wykes, Hamid and WagstaffWykes et al, 2001; Reference Irani, Platek and PanyavinIrani et al, 2006; Reference Marjoram, Miller and McIntoshMarjoram et al, 2006), but not on the ‘eyes’ test (Reference Kelemen, Keri and MustKelemen et al, 2004; Reference Irani, Platek and PanyavinIrani et al, 2006). In the study by Schiffman et al (Reference Schiffman, Lam and Jiwatram2004), genetic high-risk children who would later develop schizophrenia-spectrum disorders had lower scores on a role-taking task, which the authors considered assessed a facet of theory of mind. An association between theory of mind performance and subclinical schizotypal traits has also been found (Langdon & Coltheart, Reference Langdon and Coltheart1999, Reference Langdon and Coltheart2004; Reference Irani, Platek and PanyavinIrani et al, 2006; Reference Meyer and SheanMeyer & Shean, 2006). Pickup (Reference Pickup2006) showed that schizotypal traits analogous to positive symptoms of schizophrenia predicted poorer mentalising performance, whereas no association was found between poorer theory of mind and schizotypal traits analogous to the ‘behavioural signs’ of schizophrenia. Platek et al (Reference Platek, Critton and Myers2003) suggested that contagious yawning is part of a more general phenomenon known as mental state attribution. Consistent with this hypothesis, susceptibility to contagious yawning was positively related to performance on (other) mentalising tasks, and negatively related to schizotypal personality traits. Only in the study by Jahshan & Sergi (Reference Jahshan and Sergi2007) was there no difference between people with high schizotypy and those with low schizotypy regarding theory of mind performance. There is thus considerable evidence that mentalising impairment is a susceptibility indicator for schizophrenia and hence may be trait-dependent.

Limitations

The first limitation, to which we have already alluded, is that studies were excluded in which less common types of theory of mind tasks were used. Because there is no information on the psychometric properties of the many different tasks, this is somewhat arbitrary. In addition, the categorisation of task type is not supported by psychometric evidence. Second, the method of categorising symptom subgroups employed in this meta-analysis should be considered tentative. The main problem with our approach is that there is overlap between symptom clusters; for example, the subgrouping method used by Frith and colleagues is hierarchical, with the behavioural subgroup being the highest category. This means that patients in that subgroup could also report paranoid symptoms, but those in the paranoid subgroup could not report behavioural symptoms. As another example, participants categorised as paranoid in the study by Harrington et al (Reference Harrington, Langdon and Siegert2005b ) could also have formal thought disorder (which was indeed the case). However, in spite of this limitation, we believe that the results of the subgroup analyses in this meta-analysis are valuable. This is statistically supported by the homogeneity analyses, which show that the clustering of symptom subgroups did not result in more variation than would be expected from sampling error alone and that it is plausible that the studies within the subgroup analyses are comparable.

Recommendations for future research

The results and limitations of this meta-analysis lead to some recommendations for future research. First, research focusing on the mentalising process itself is necessary, addressing questions on what components it comprises and on how to operationalise them. As has already been pointed out by Harrington et al (Reference Harrington, Siegert and McClure2005a ), it is also important to establish the psychometric properties of theory of mind tasks. Second, the finding that the deficit in theory of mind in schizophrenia is perhaps trait-dependent rather than state-dependent implies that the deficit may also be present before illness onset. Therefore, there may be a role of mentalising impairment in the early detection and prediction of schizophrenia, requiring a longitudinal study examining theory of mind abilities in people at risk of developing schizophrenia.

Third, the finding that theory of mind impairment may be trait-dependent also brings to mind a comparison with autism-spectrum disorders. An impaired ability to understand mental states has been described as one of the core symptoms of such disorders (Reference Yirmiya, Erel and ShakedYirmiya et al, 1998). However, although the risk of psychotic disorder is elevated in individuals with autism-spectrum disorder (Reference Stahlberg, Soderstrom and RastamStahlberg et al, 2004), most of them will not develop a psychotic disorder. Future research should focus on what the commonalities and differences are with regard to theory of mind in these disorders. Abu-Akel & Bailey (Reference Abu-Akel and Bailey2000) for example suggested that there might be different forms of impairment of theory of mind. They argue that, unlike people with autism-spectrum disorders, people with schizophrenia do not lack an understanding that others have mental states; instead, they may overattribute knowledge to others or apply their knowledge of mental states in an incorrect or biased way. Thus, an interesting research topic would be a comparison of the mentalising abilities of groups of people with these two disorders.

Lastly, social impairment is one of the most disabling clinical features of schizophrenia and it is well known that it is often present before illness onset (e.g. Reference Niemi, Suvisaari and Tuulio-HenrikssonNiemi et al, 2003). Since theory of mind impairment appears to be trait- rather than state-dependent in schizophrenia, this deficit may have a role in the development of social impairment. However, evidence of a relationship between theory of mind performance and social functioning is lacking and should be an aim of future research.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from ZorgOnderzoek Nederland/NWO-Medische Wetenschappen, project 2630.0001.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.