9.1 IntroductionFootnote *

The current crisis of West European social democratic parties has led to a renewed interest in the electoral fate of this party family. While we observe a general decline of social democratic vote shares in the past twenty years, large variation exists between countries. Political science research thus needs to address both which factors determine the general downward trend of social democratic parties, and at the same time the factors that explain variation in support for these parties across countries and time.

A large amount of research has identified the structural transformations that have led to increasingly difficult electoral context conditions for social democratic parties (see Chapter 1, this volume, for a discussion). As many studies have argued and shown (e.g., Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018), socioeconomic changes of postindustrial societies such as changing occupational structures, higher education, and the changing role of women in society have deeply transformed the demand side of political competition in Western Europe by affecting both the composition and size of sociostructural electoral potentials as well as voter demands and preferences. More specifically, a shrinking industrial working class, the emergence of a core left-wing constituency of middle-class voters, and the politicization of second-dimension issues across all countries of Western Europe have created pressures for social democratic parties to adjust their programmatic profiles to changing demands of their old and new electoral constituencies, both with regard to economic policies, as well as with regard to increasingly salient sociocultural issue positions (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Dalton Reference Dalton2018; Benedetto et al. Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2020). These programmatic-strategic decisions in a multidimensional space may even come with electoral trade-offs (certainly across the entire electorate, but to a weaker extent also within the left electorate, see Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022), as appealing to certain voters might not resonate with, or even alienate, other voters.

Hence, social democratic parties in the first half of the twenty-first century find themselves in a pluralized issue space and an electorally fragmented party system, which entails generally smaller vote shares for mainstream parties, particularly where electoral systems have allowed new challengers such as green and left-libertarian and radical right parties to become established political actors. The chapters in the first part of this book (e.g., Chapters 3, 5, and 6, this volume) show that social democratic parties have lost voters in substantive shares to all sides, but most strongly so both to the moderate right parties and to the other parties on the left. This new context makes it very difficult for social democratic parties to achieve the high vote shares they were able to hold in the twentieth century, not primarily because of strategic mistakes, but for more structural reasons.

That being said, and within certain boundaries, social democratic parties are not just victims of long-term macrostructural trends, but they also have agency to position themselves in the transformed political space, and to thereby shape and form new electoral coalitions. Different ideological-programmatic strategies are likely to appeal to different electoral groups, and the size and behavior of these groups will, in turn, affect the electoral support for social democratic parties. The introduction to this book (cf. Häusermann and Kitschelt, this volume) discusses both the current positioning and the hypothetical strategic options for social democratic parties in detail. In this chapter, we operationalize these strategic options and study the support they receive among the entire electorate and among the potential social democratic voters.

Indeed, much public and political debate has focused on how social democratic programmatic strategies might affect their electoral fate. However, only few studies directly and empirically examine the support yielded by various social democratic programmatic strategies, and the conditioning factors of these yields (e.g., Arndt Reference Arndt2013; Karreth et al. Reference Karreth, Polk and Allen2013; Rennwald and Evans Reference Rennwald and Evans2014; Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019, Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020; Rennwald Reference Rennwald2020; Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022; as well as the chapters by Karreth and Polk and by Bremer, this volume). Furthermore, the study of voter reactions to programmatic shifts is very difficult to study, since observational variation across time and space is rather limited and correlates with further contextual factors. As a result, while we have abundant knowledge about how individual-level preferences on several dimensions of political conflict have changed (and how their relationship with electoral preferences for different parties has changed, see, e.g., Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015) in postindustrial societies, it remains still rather unclear how these preferences play out in relationship and in reaction to variation in Social Democrats’ programmatic positions: Which programmatic profiles are most strongly supported? Are economically progressive voters alienated by culturally progressive positions? Do culturally progressive voters support or reject decidedly left-wing economic positions? Is a Centrist strategy at all supported by voters in the left field? And how much support is there indeed for a Left National programmatic strategy (in the general electorate, as well as in the potential social democratic electorate)?

Several contributions in this volume use observational data to help us better understand which groups of voters social democratic parties have lost and where these voters have gone (see the chapters in Part I of this volume). However, the question of how these voter flows are related to programmatic choices by social democratic parties themselves is indeed difficult to study with observational data, since social democratic parties in West European countries have so far mostly adopted programmatic strategies that are either Centrist or a mixture of Old and New Left (cf. Figures 1.6 and 1.7, Chapter 1, this volume). For this reason, we instead use original survey data (Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022) to analyze voters’ responses to different social democratic programs through vignettes. We presented respondents in six countries (Austria, Denmark, Germany, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland) with stylized social democratic programs that vary in terms of their positions on nine key policy issues and asked respondents to rate these different programs.

Based on these data, we provide evidence on the support levels for four strategic issue bundles: Old Left, New Left, Centrist, and Left National. We also study how these programs play out against the four specific (matched) programmatic competitors (Old Left vs. Radical Left; New Left vs. Green Left; Centrist vs. Moderate Right; Left National vs. Radical Right); in other words, we study how voters would choose between two matched competing programs. Thereby, we want to gauge the elasticity to programmatic choices, that is the extent to which and the conditions under which programmatic strategic choices by social democratic parties indeed matter for pivotal voter groups.

We find that the popularity of the four different social democratic strategies varies strongly between the electorate as a whole on the one hand and the potential social democratic electorate on the other. In short, Centrist and Left National programs are popular in the overall electorate, but the support for these programs mostly stems from people who see it as unlikely that they would ever vote social democratic and/or who place themselves clearly on the right of the left–right ideological spectrum. Among the potential social democratic/left-wing electorate, however, the New Left and the Old Left programs generally enjoy clearly higher levels of support. We corroborate and develop this finding further by showing that Old and New Left programs are strongly supported by left-wing voters in general. Both economically and socioculturally progressive voters support social democratic parties for advancing pronouncedly left-wing positions on both axes. We find little evidence overall for a trade-off between “redistributive politics” and “identity politics,” as left-wing voters support both Old and New Left programmatic orientations of social democratic parties. By contrast, more conservative voters (on either economic or sociocultural issues) are unlikely to react positively to social democratic programs geared toward their programmatic preferences. They seem overall hardly responsive to the programmatic offer of social democratic parties, at all. These findings seem to suggest that (limited) vote gains in the center-right spectrum of the ideological space may be due to factors other than programmatic supply (such as competence-attributions and campaign effects).

Finally, identifying the potential social democratic electorate and using ideological preferences as a determinant of support for different programmatic strategies also highlights important differences across countries in the extent to which the left–right divide has realigned around a definition of progressive politics in both sociocultural and economic terms: In the strongly (and early) realigned countries (Austria, Sweden, and Switzerland), where social democratic parties have taken clearly progressive positions on both dimensions over the past decades, left-wing voters clearly support both Old and New Left programs equally strongly, and they demarcate themselves quite clearly from Centrist and Left National programs; by contrast, programmatic preference profiles are less differentiated in Germany, Spain, and Denmark, where in general Old Left programs enjoy rather high levels of support throughout the ideological spectrum, and where Centrist and Left National programs yield higher relative levels of support even among more centrist potential social democratic voters.

9.2 Four Social Democratic Strategies and Expected Yields

Conceptualizing the four potential social democratic programmatic strategies (see Figure 1.5) in terms of concrete policy positions raises the question of which issues to select to validly approximate these strategies across countries. First, while traditional economic-distributive questions over the extent of state control over market processes and market outcomes (such as social insurance transfers, employment regulation, and taxation) remain important, another, equally economic-distributive set of policy issues that encompasses questions of social investment versus social consumption now structures political preferences as well, especially among left-wing middle-class voters (Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020; Bremer Reference Bremer, Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022). Social investment policies seek to increase social security and social welfare by producing, mobilizing and preserving human capital and capabilities (Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022). Early childhood education and care policies, active labor market policies, or educational investments are typical examples of such social investment policies, which by now have become integral parts of the welfare politics agenda alongside the more traditional policies of income (re-)distribution (Morel et al. Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012; Hemerijck Reference Hemerijck2013). Hence, in approximating programmatic strategies we need to include redistributive, regulative, as well as investive social policy appeals.

Second, we also need to include a range of issues to reflect positioning on the sociocultural dimension of party competition. While the “new social movements” of the 1960s and 1970s mobilized issues around basic principles of societal organization and self-determination (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi Reference Kriesi, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999), the past thirty years have seen the increasingly salient emergence of a broader range of issues that can be related to different aspects of equality and universalism (e.g., with regard to gender equality, minority rights, inclusiveness more generally) and very prominently also include questions of immigration and multiculturalism policies/integration (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010). Environmental policies have been politicized by the new social movements from the 1980s onwards along the same lines as questions of universalism more generally, which is why they have tended to load on the same dimension of political conflict in most countries (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). However, with the broader and more recent politicization of climate change policies, this area of policymaking has received a more regulative and economic connotation, as well, so that it will be an empirical question to see if voters respond to appeals on environmental protection along the same or different patterns as to more traditional sociocultural appeals.

Based on these key issues, we devise four ideal-typical programmatic bundles to approximate programmatic strategic options for social democratic parties, and we develop general expectations about their electoral yield among particular (sub-)groups of voters. We will present the exact operationalizations in the subsequent section on data and research design.

(1) Old Left. The positions that determine the Old Left strategy focus on decidedly progressive positions when it comes to economic redistribution, market regulation, and especially social consumption-oriented social policies. With regard to questions of social investment or second dimension issues, an Old Left strategy allows for more leeway (except for excluding a decidedly restrictive-particularist stance). We expect an Old Left strategy to appeal most strongly to the traditional support base of social democratic parties, which is interested in redistribution. It is an open question, however, to what extent culturally progressive voters would support such a strategy. We also expect the Old Left strategy to be most strongly supported in contexts where electoral realignment (i.e., the focus of party competition on radical right vs. green and left-libertarian politics) has come about late (as, for instance, in Germany), and where welfare states are generally under-developed (e.g., Spain).

(2) New Left. A New Left programmatic strategy is characterized by a combination of investment-oriented social policies and progressive positions on questions such as gender equality, multiculturalism, and immigration, as well as a strong position on measures countering climate change. Parties with a New Left program should particularly attract the support of voters that favor progressive second dimension positions. The question is to what extent it alienates other voter groups, such as traditional, economically left-wing voters. We expect the strongest levels of support for New Left strategies in contexts that are characterized by strong electoral realignment (e.g., Austria, Switzerland, and to some extent Sweden and Denmark).

(3) Centrist Left. Centrist social democratic parties take moderate positions on economic redistribution and equally moderate positions on second dimension issues. They are thus less economically left-wing than the Old Left and less culturally progressive than the New Left. They favor social investment over social consumption. Centrist Left parties aim at attracting moderate voters and potentially the median voter position. While we expect Centrist programs to resonate more strongly with center-right voters, we also know from the existing literature that Centrist positions are likely to yield only modest and volatile electoral gains (e.g., Karreth et al. Reference Karreth, Polk and Allen2013; see also the Chapters by Bremer and by Karreth and Polk, this volume), because electoral choices “in the center” tend to be based on other factors than purely programmatic appeals as well (e.g., competence, experience, cf. Green and Jennings Reference Green and Jennings2017). Therefore, we expect rather moderate levels of support among left-wing voters across all countries.

(4) Left National. Left National (or left-authoritarian) social democratic party strategies combine positions that favor economic redistribution and social consumption but take decidedly less progressive positions on second dimension issues and environmental policies, and especially emphasize more restrictive policies on immigration and multiculturalism. Left National strategies are aimed at voters that hold economically left-wing positions but more nationalist and authoritarian positions on the second dimension. The interesting question is whether these programs indeed resonate with voters who self-position on the left economically, and the extent to which they alienate culturally progressive voters. We would expect the strongest overall potential support bases for Left National programs to emerge in those countries where welfare politics have reached a certain saturation, and where second dimension politics are strongly established (most likely in Denmark and Sweden).

These programmatic bundles also address specific competitors of Social Democracy. We identify four key rivals of social democratic parties, which have to varying degrees been successful in attracting former or potential social democratic voters: the Radical Left, the Green Left, the Moderate Right, and the Radical Right. We chose these four rivals because they are key components of the pluralized and fragmented party systems in Europe: most social democratic parties, particularly in highly proportional systems, face a couple of rivals on the left and a couple of rivals on the right. They are also the parties that are the key competitors of the Social Democrats on either side of the economic dimension (Radical Left and Moderate Right) and on either side of the cultural dimension (Green Left and Radical Right).

We see each of our four strategies as most directly relevant to competition with one of these four rivals. Thus, the Old Left strategy is one that is most threatening to radical left parties, who campaign on economic redistribution and social consumption. The New Left strategy is closest to that of green and left-libertarian parties, who share a similar mix of progressive cultural positions mixed with social investment. The Centrist Left strategy may be successful in stealing voters from moderate right parties, who are moderate on liberal-authoritarian issues and on the economy. Finally, the Left National strategy might be a way to counter the success of radical right parties, who share a clearly conservative stance on second-dimension issues (particularly immigration) but are more moderate on economic issues (often described as welfare chauvinist or welfare authoritarian, see, e.g., Roeth et al. Reference Roeth, Afonso and Spies2017; Enggist and Pinggera Reference Enggist and Pinggera2022; Rathgeb and Busemeyer Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022). It is important to emphasize, however, that all four social democratic strategies are distinct from the competitor programs. For example, Left National programs are economically more to the left and culturally more moderate than the ideal-typical program of actual radical right parties.

9.3 Data and Measurement

We use original data from a survey conducted in six West European countries with 2,000 respondents each in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland (Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022). The fieldwork was conducted in cooperation with a professional survey institute (Bilendi) using their online panels. The target population was a country’s adult population (>18 years). The survey sample was based on population quotas for age × education and age × gender. The total sample counts 11,647 completed interviews that were conducted between October 2020 and March 2021.

In the survey, we implemented a set of questions aimed at eliciting attitudes toward different party programs. The part of the survey using the vignettes was fielded right at the beginning of the survey in order not to prime respondents with other questions asked about political attitudes or electoral preferences. At the start of the survey, we told respondents that we would present them with two potential programs of the social democratic party in their country; the precise wording asked respondents to imagine that two candidates are in the running for leader of the social democratic party. Each of them presents their program for the party. We then asked respondents which of the two programs they would rather support. Each respondent completed four of these comparisons and indicated both a choice variable and a rating of both presented vignettes (scale 1–7, used for the analyses in this chapter). In the second part of the vignette study, we asked respondents to compare a hypothetical program of the social democratic party of their country with the program of a different party, which we did not label. Again, respondents completed four comparisons and gave both a choice answer (which we use in the second part of the analysis in this chapter) and a rating of each vignette. This survey design can be used both for conjoint analyses (in the fully randomized version, cf. Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022), as well as for observational vignette studies, as we do in this chapter, since we oversampled combinations of policy positions that reflect the four potential strategies of social democratic parties.

For these vignettes, we formulated the specific versions of our four ideal-typical social democratic programs, shown in Table 9.1. These ideal-typical programs are based on positions on nine policy areas. We chose these with the aim of covering the key policy debates in contemporary European polities. For some policies, we did not identify specific positions but deliberately let the position vary randomly, if the programmatic orientation does not require a particular position but might allow for vagueness or variance on the issue (e.g., the New Left profile on public subsidization of early retirement; or the Old Left profile with regard to a ban on head scarves for civil servants). In some cases, we narrowed the possibility for random variation down to a narrower subset of options (e.g., the Centrist profile on public subsidization of early retirement was allowed to vary randomly between “abolish” or “leave unchanged” but excludes the option of expanding early retirement schemes for everyone).

Table 9.1 Ideal-typical social democratic programs

| Social democratic programs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Old Left” | “New Left” | “Centrist Left” | “Left National” | |

| Public subsidization of early retirement | Expand for everyone | Randomized (expand, leave or abolish) | Leave unchanged or abolish | Expand for everyone |

| Public childcare services | Randomized position | Expand strongly | Expand strongly | Leave unchanged |

| Inheritance tax on private wealth | Increase | Increase | Increase or leave unchanged | Increase |

| Immigration regulation | Controlled, without upper limit | Controlled, without upper limit | Controlled, with or without upper limit | Controlled with upper limit or reduction |

| Ban on head scarves for civil servants | Randomized (yes or no) | No | Randomized (yes or no) | Yes |

| Legal quota for women on executive boards | Randomized (none, 30% minimum or 50% mandatory) | 50% mandatory | 50% mandatory or 30% minimum | 30% minimum or none |

| Taxation of CO2 emissions | Randomized (no, moderate or massive increase) | Increase massively | Increase moderately or no increase | Increase moderately or no increase |

| Employment protection in manufacturing | Increase strongly | Leave unchanged | Leave unchanged | Increase strongly |

| Public control of rent prices in urban areas | Ban or slow down rent increases | Ban or slow down rent increases | Slow down or leave unchanged | Ban or slow down rent increases |

In the second part of the vignette study, in which we had the respondents compare a social democratic to a matched competitor program, we showed only the vignettes (Table 9.2) for the competitor programs (hence no randomization for the competitor programs) and we oversampled the social democratic vignette programs in a way as to ensure to have at least 500 direct comparisons between the social democratic variant and its matched competitor per country. In this scenario, respondents were told that they are about to compare the program of the main social democratic party of their country to the program of a competitor party (without naming which one this was).

Table 9.2 Ideal-typical competitor programs

| Competitor programs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Radical Left” | “Green Left” | “Moderate Right” | “Radical Right” | |

| Public subsidization of early retirement | Expand for everyone | Leave unchanged | Abolish | Leave unchanged |

| Public childcare services | Leave unchanged | Expand strongly | Leave unchanged | Leave unchanged |

| Inheritance tax on private wealth | Increase | Leave unchanged | Reduce | Leave unchanged |

| Immigration regulation | Controlled, without upper limit | Controlled, without upper limit | Controlled, with upper limit | Reduction |

| Ban on head scarves for civil servants | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Legal quota for women on executive boards | 50% mandatory | 50% mandatory | None | None |

| Taxation of CO2 emissions | Increase moderately | Increase massively | Increase moderately | No increase |

| Employment protection in manufacturing | Increase strongly | Leave unchanged | Leave unchanged | Increase strongly |

| Public control of rent prices in urban areas | Ban rent increases | Slow down rent increases | Leave unchanged | Leave unchanged |

Thus, we asked respondents to choose between an Old Left and a Radical Left program; between a New Left and a Green Left program; between a Centrist Left and a Moderate Right program; and between a Left National and a Radical Right program. For each of these specific comparisons, we also presented respondents with a set of entirely random social democratic profiles, so we can compare (for instance) how a New Left program matches up against a Green Left program with how a random social democratic program matches up against a Green Left program. The random profiles are fully randomized in all attribute levels that are in the realm of social democratic programs (see Table 9.1).

In our analyses, we also make use of two preference dimensions. These are constructed by extracting the first rotated factor from a factor analysis of a set of attitude questions (agree–disagree statements); the factor analyses were run separately on each set of questions and for each country. The questions making up each preference dimension are shown in Table 9.3.

Table 9.3 Economic and cultural attitudes: measurement

| Preference dimension | Agree–disagree statements |

|---|---|

| Economy |

|

| Culture |

|

9.4 Analyses

The analyses are structured as follows. We start with a presentation of the findings of the pooled sample of data across all six countries (Section 9.4.1), because the main patterns of support are similar across all country contexts. This first section compares the relative support the four different programmatic strategies receive in the electorate as a whole and within the social democratic electorate. We then delve deeper into the analysis of relative support among specific subgroups of voters, defined by ideological self-placement and by attitudes on economically or culturally progressive policies to show that there are no significant trade-offs between Old and New Left strategies within the progressive electorate. We end this first section of the analysis studying the determinants of choice between social democratic programs and their matched competitors, showing that targeted programmatic appeals yield reactions within the left field but do not seem to yield substantive responses among conservative and right-wing voters. In a second part of the analysis (Section 9.4.2), we discuss program support by left–right self-positioning differentiated by countries in order to show how the electoral realignment of the left field has progressed to different extents in the six countries.

9.4.1 Overall Support for Social Democratic Strategies

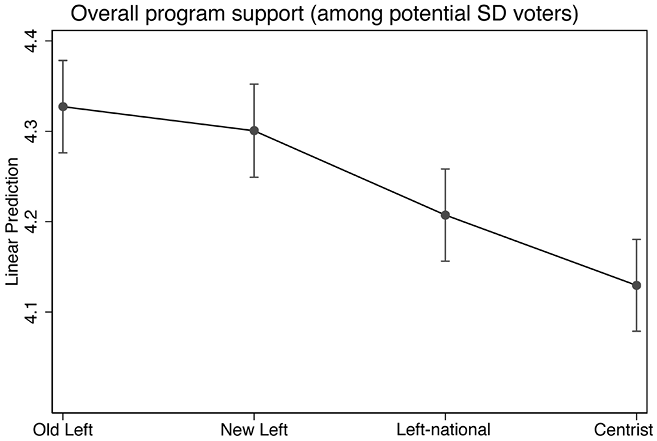

The findings shown in this section are based on linear regressions predicting the rating of program vignettes (see Tables 9.1 and 9.2), controlling for education, sex, age, and income. Figures 9.1 and 9.2 jointly show how strongly the popularity of different social democratic strategies varies between the electorate as a whole and the potential social democratic electorate. Figure 9.1 reports predicted levels of support (on a scale from 1 to 7) for the four social democratic program types in the pooled sample. Within the entire electorate, a Left National social democratic program enjoys the highest level of support, followed by the Centrist Left program and then the Old Left program. New Left programmatic appeals resonate significantly less in the overall electorate. This main finding, that is, the overall relatively higher support level for Left National and Centrist Left programmatic strategies as opposed to New Left strategies in particular, is confirmed across all country contexts (not shown): Left National and Centrist Left programs also yield the highest levels of support in most countries (Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, and Denmark in particular), while Spain and Germany also exhibit almost equally strong support levels overall for Old Left social democratic strategies. New Left programs received lowest average support in all countries in the entire electorate.

Figure 9.1 Support for four social democratic programmatic strategies in the entire electorate (all voters)

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

Figure 9.2 Support for four social democratic programmatic strategies among the potential social democratic electorate (sample: all voters with a propensity to vote (ptv) social democratic >5 and/or left–right self-positioning <5).

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

At first glance, these findings suggest that there might indeed be a very large “demand” for a Left National programmatic strategy. However, Figure 9.2 then shows that these patterns do not adequately reflect the attitudinal profile of potential social democratic voters. We define potential social democratic voters as those who fulfill one (or both) of the following conditions: (a) They indicate a voting propensity of 5 or higher for the social democratic party (on a scale from 0 to 10 for voting propensities). While voting propensities necessarily introduce a certain level of endogeneity to the analysis, we think that the propensity to vote (ptv) score captures whether a voter would in general seriously consider voting for this party family. (b) We add to this group all voters who self-position at a level below 5 on an ideological scale ranging from 0 (left) to 10 (right). We define the potential social democratic electorate in this very broad way in order to include also voters who self-position on the left but may disagree with the situational, current orientation or leadership of the social democratic party. Our definition of the potential social democratic electorate thereby encompasses 54% of the entire sample.

Figure 9.2 then clarified that the relatively stronger support for the Centrist Left and Left National programs as observed in Figure 9.1 stems to an overwhelming degree from responses by voters who are outside the potential electorate for the social democratic party. Among potential social democratic voters, however, New Left and Old Left programs are clearly more strongly supported than Left National and Centrist Left programs. This patterns again broadly holds across country contexts. However, we do see differences that are consistent with what we know about the more strongly realigned social democratic electoral potentials in Austria, Switzerland, and Sweden, as opposed to Germany and Spain (see Chapter 1 for a presentation and discussion of the different distributions of social democratic voting propensities across these countries). In the former three countries, New Left programs receive the strongest levels of support among the potential social democratic electorate, while Old Left programs are most favorably evaluated in Germany and Spain. Only in Denmark do we see indistinctive levels of support for all four programmatic orientations, with no significant differences in the levels of support. The main point here, however, is that the patterns of programmatic preferences look quite different when we focus on the electorate overall, as compared to the potential social democratic voters. Hence, average support levels for Centrist Left and Left National orientations may give an erroneous impression about the likely payoffs of such strategies, given that we know that electoral markets are segmented (Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair1990; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010) and that voters tend to choose parties not across the entire spectrum but from a predefined “consideration set” (Oscarsson and Rosema Reference Oscarsson and Rosema2019).

The fact that Old and New Left programs resonate most strongly with voters in the broadly left spectrum of the electorate is also confirmed when we predict program rating by left–right self-positioning. Figure 9.3 shows how ideological self-positioning relates to support for program orientations in the full sample. The figure also includes the relevant information about the distribution of voters in the ideological spectrum, both for all voters and for potential social democratic voters. Only the combination of the estimated support and the distribution of voters allows us to gauge likely payoffs of different strategies. Very clearly, one can see that potential social democratic voters are predominantly situated in the center-left ideological spectrum, and we can see that both Old and New Left programs on average receive distinctively more support in this section of the electorate than Centrist Left and Left National social democratic programs (remember that our vignettes define even these more conservative programs in ways that are still consistent with generally moderate or left-wing positions on all issues). We also observe that the New Left program polarizes slightly more than the Old Left program, a finding that will be corroborated across country contexts in the comparative analyses in Section 9.4.2. On the other hand, both Centrist Left and Left National program receive similar levels of support in the center of the ideological spectrum, as well as clearly on the right.

Figure 9.3 Support for four social democratic programmatic strategies by left–right self-positioning (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0)

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

We continue the abovementioned analysis with a focus on more specifically defined groups in terms of attitudes. We thereby look at the economic dimension of attitudes and the sociocultural dimension of attitudes, because academic and political debates oftentimes focus on an alleged dilemma that might emerge between Old and New Left strategic appeals: They debate the question whether social democratic parties should either try to appeal to voters with more radically left-wing economic positions on redistributive and regulative issues, or whether they should rather appeal to a culturally progressive electorate. The assumption is that voters who are economically strongly to the left might be alienated by a focus on New Left (so-called identity politics) appeals, while culturally progressive voters may resent a too radical economically left-wing program.

Our analyses in Figures 9.4 and 9.5 show that there is no trade-off between these two programmatic options from the perspective of voters: Both economically and culturally progressive attitudes clearly predict support for both Old and New Left strategies. Figure 9.4 in particular underlines that economically progressive (i.e., radical left) voters also support New Left programs, while showing somewhat lower levels of support for Left National programs (which – importantly – are equally progressive economically, and deviate only to the more conservative side on sociocultural issues) and clearly lowest levels of support for (economically) Centrist Left programs. In all countries, Old or New Left options receive the highest levels of support. The weakest support for Centrist Left orientations holds in all countries. Only in Denmark and Germany is the difference in support for the New Left and Left National option (as second ranked) not significant. These analyses defy the widespread narrative that economically left-wing voters are alienated by New Left policy positions. Quite the contrary: Economic leftist voters are on average even the staunchest supporters of New Left programmatic orientations in Austria, Switzerland, and Spain.

Figure 9.4 Support for four social democratic programmatic strategies by position on the economic dimension (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0)

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

Figure 9.5 Support for four social democratic programmatic strategies by position on the cultural dimension (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0)

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

We also see that economic attitudes polarize less when it comes to programmatic preferences than sociocultural attitudes, by comparing Figures 9.4 and 9.5. Figure 9.5 shows the same analysis for sociocultural programmatic preferences. Again, Old and New Left programs both garner the highest levels of support among the culturally left-wing voters, among which most potential social democratic voters can be found. Here, the New Left orientation comes out on top, a finding that holds in all countries (only in Germany and Spain does the Old Left orientation receive the same level of high support among culturally very progressive voters as the New Left orientation). A key finding from Figure 9.5, however, refers to the polarizing effect of both New Left and Left National programs depending on cultural attitudes: The New Left program is least supported among culturally conservative voters (consistent in all countries), whereas the Left National program comes out on top. The strong polarization around the Left National program is of particular relevance, as it highlights that such a program seems to appeal mainly to voters outside of the social democratic potential and that it implies the risk of alienating large shares of voters within this potential.

The analysis so far has focused on the levels of support for different social democratic programs in the overall electorate and among subgroups defined by attitudinal profiles. However, the payoff of a programmatic strategy not only depends on the support level but also on the question whether voters – and which voters in particular – would indeed choose the social democratic version of a particular program when compared to the relevant competitor party. In other words, even though we know that many economically left-wing voters show high support for a New Left program, the question is whether they would really prefer a New Left social democratic party if voting for a green and left-libertarian party is also an option? In this final section, we ask precisely this question, predicting choices between matched party vignettes based on the party profiles interacted with the same attitudinal variables as mentioned earlier.

For this analysis, we presented respondents with two vignettes to choose from: One was a fixed “competitor” program (Green Left, Radical Left, Moderate Right, or Radical Right, see Table 9.2), while the other one was either the “matched” social democratic variant (respectively, New Left, Old Left, Centrist Left, or Left National, see Table 9.1) or a program randomly composed from all the possible programmatic elements within the realm of the social democratic programs. We did tell respondents that one of those was a social democratic program, but neither of these two programs were explicitly labelled in terms of a party. Hence, the respondent did not know which of the vignettes was supposed to refer to the social democratic profile and which one to the competitor. We asked respondents to indicate which of the two programs they would prefer. Each respondent saw four comparisons.

This design allows us to compare the probabilities of choosing the matched social democratic program over the competitor program to those of choosing a random social democratic program over the competitor program. In intuitive and substantive terms, this means that we can evaluate whether and how much the particular programmatic profile of a social democratic party matters for voters’ choice between the social democratic option and the “original.” If the choice probabilities between the random and the competitor programs differ from the choice probabilities between the specific and the competitor program, programmatic appeals indeed matter and there is actual competition on these programmatic grounds. If they do not, then the actual programmatic choices by social democratic parties seem much less relevant (because voters may go for the “original” in any case or because the social democratic party may not even belong to their consideration set). Our estimations again exclude those respondents indicating a voting propensity of 0 for Social Democrats.

We present the findings separately for the four competing party families. Since there are too many possibilities of comparison to show them all, we show only the theoretically most interesting ones and discuss the others in the text. These are the key findings: Our estimates show that the New Left and Old Left party strategies indeed manage to increase the chances for social democratic parties to be chosen compared to their green left and radical left competitors both among culturally and economically progressive voters. When competing with moderate right or radical right parties, however, it does not seem to make as strong a difference whether the Social Democrats propose any (random) program or the specifically matched profile: Regardless of the particular programmatic profile of the social democratic vignette, economically and culturally more conservative voters generally prefer the moderate and radical right options over the Social Democrats anyway. This finding reinforces the abovementioned findings according to which the chances of attracting new voters seem much better among center-left voters than among the more conservative parts of the electorate.

We start with the choice between a green and left-libertarian and a social democratic party. For this comparison, we are interested whether progressive voters would indeed be more likely to choose the social democratic party over a green and left-libertarian party if the social democratic party were to propose a New Left program. For this comparison, both the behavior of socioculturally left-wing voters (the core electorate of the green and left-libertarian parties) and of economically left-wing voters (potential gains within the left field) are of relevance. Figure 9.6 shows the estimates for these two groups side by side. For economically left-wing voters (Figure 9.6(a)), the probability of choosing a social democratic party as opposed to the Green Left increases well beyond 50% in case of a New Left program. These voters are then more likely to vote social democratic than Green Left, whereas their propensity to vote social democratic remains around 50% for a random social democratic program. Among culturally progressive voters (Figure 9.6(b)), the New Left program is also much more attractive than a random social democratic program. However, among these voters the green and left-libertarian party always remains the first choice, even if the social democratic competitor “emulates” its program.

Figure 9.6 Social Democrats vs. Green Left: predicted probabilities of choosing the social democratic party over the green and left-libertarian option by attitude (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0)

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

Figure 9.7 presents the same estimations for the comparison between social democratic and radical left programs, again focusing on voters on the left of the ideological spectrum. We turn first to economically left-wing voters (Figure 9.7(a)). Among these voters, an Old Left program is much more popular than a random social democratic program, and the probability for it to be chosen lies well above 50%. Among voters with strongly progressive cultural attitudes, an Old Left program resonates in general less strongly but is still clearly preferred to a random social democratic program. This is important, as it illustrates that culturally progressive voters also support economically very left-wing programs rather than centrist policy appeals (given that a randomized social democratic program is by definition more moderate than the Old Left program).

Figure 9.7 Social Democrats vs. Radical Left: predicted probabilities of choosing the social democratic party over the radical left option by attitude (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0)

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

Figures 9.8 and 9.9 show that positional accommodation in terms of a “matched” program much less strongly affects the choice between a social democratic and a moderate right or radical right program. Here, we again focus on the voters these programs are most likely meant to appeal to. For the Moderate Right, this means looking at voters at or near the center on either economic or sociocultural issues. Among voters with average or slightly progressive attitudes, a Centrist Left social democratic program is slightly preferred slightly to a random social democratic program, but the difference is much less pronounced than in the previous figures. Overall, centrist voters have relatively high propensities to vote for social democratic parties anyways, irrespective of whether they propose a clear Centrist Left program or any program. The choice between Moderate Right and Left therefore seems mostly predetermined for both dimensions of political conflict and possibly also strongly affected by other variables such as competence attributions or party identification. Overall, however, choices for or against this competitor depend comparatively less on the programmatic offer made by Social Democrats, and there seems relatively little to gain or lose via specific targeted programmatic appeals.

Figure 9.8 Social Democrats vs. Moderate Right: predicted probabilities of choosing the social democratic party over the moderate right option by sociocultural attitude (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0)

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

Figure 9.9 Social Democrats vs. Radical Right: predicted probabilities of choosing the social democratic party over the radical right option by attitude (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0)

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

Finally, for the Radical Right, we focus on voters who are either moderately or decidedly conservative regarding sociocultural issues. Figure 9.9 shows that a Left National program barely affects choice for the social democratic parties among culturally conservative voters, that is, the key constituency this program is meant to appeal to. Culturally conservative voters overall have a very low probability to vote for a social democratic program. A specific Left National appeal increases this probability slightly but only among more moderately conservative voters. However, the probability of choosing the social democratic option never reaches 50% and is even below 30% among voters with clearly conservative attitudes. For them, the specific program social democratic parties propose do not seem to make a difference, at all.

9.4.2 Comparative Perspective

We conclude our empirical analysis with a comparative perspective across the different country contexts in our study. As shown and discussed in Chapter 1, earlier strategic positionings and choices as well as country-specific dynamics of party competition have created different contexts for social democratic parties in terms of their current electorates, as operationalized through voting propensities. In Austria, Switzerland, and Sweden, voting propensities for the social democratic parties are clearly and almost linearly linked to left self-placement, as well as to both economically and culturally progressive attitudes. In these countries, social democratic parties and their voters have realigned at the opposite pole of radical right parties. In Germany and Spain, on the other hand, the highest propensities to vote social democratic are found among centrist and left-of-center voters. Hence, the social democratic parties in these countries appeal more to voters with more moderate ideological profiles, and it seems that these parties are perceived as more centrist by voters. By contrast, voters with clearly progressive economic attitudes are less likely to vote social democratic. Finally, Denmark presents a somewhat different picture, as well, but rather with regard to the cultural ideological dimension. As in Germany and Spain, the propensity to vote social democratic is highest among moderately left-of-center voters, but the striking observation is that cultural attitudes do not correlate clearly with social democratic voting propensity: Both progressive and more centrist voters report similar levels of support for the social democratic party. One might think that the very recent shifts of the Danish Social Democratic Party program are at the root of this pattern, since it has moved strongly to the center on both economic and – in particular – cultural positions.

Figures 9.10 and 9.11 show that this differential orientation of social democratic parties across countries is consistently reflected in the extent to which ideological dimensions relate to support for particular strategic profiles, and in the extent to which these strategies polarize the electorate. Figure 9.10 strikingly illustrates how strongly realigned the party competition in Austria, Switzerland, and Sweden is: Support for New Left and Old Left programs strongly increases with left self-positioning, while support for Centrist and Left National programs decreases with left self-positioning. In other words, only voters who self-define as “right-wing” support Centrist Left and Left National programmatic profiles and show decidedly lower support for the Old and New Left programs. However, in those ranges of the ideological spectrum where most potential social democratic voters concentrate, support for Old and New Left programs is clearly highest. This not only implies that social democratic parties in these countries may be unable to appeal to more center-right voters, at all, but it also implies that Centrist Left and Left National appeals may alienate large parts of their potential electorate.

Figure 9.10 Support for different social democratic programmatic strategies by left–right self-positioning (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0), Austria, Switzerland, and Sweden

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

Figure 9.11 Support for different social democratic programmatic strategies by left–right self-positioning (sample: all voters except ptv social democratic = 0), Germany, Spain, and Denmark

Data: Abou-Chadi et al. (Reference Abou-Chadi, Häusermann, Mitteregger, Mosimann and Wagner2022).

By contrast, left–right self-placement polarizes much less in Germany and Spain (Figure 9.11). In these countries, Old Left programs enjoy overall highest support, across the ideological spectrum. Moreover, left–right self-positioning differentiates more strongly between New Left and Left-National programs than between Old Left and Centrist programs. Overall, the findings for Germany and Spain show that support for an Old Left programmatic orientation is particularly strong in the electorate, including in those parts where the share of social democratic voters is very high. Finally, we again see a somewhat different pattern in Denmark: Most potential social democratic voters have relatively indistinctive preferences between the four party strategies. However, the Left National program is clearly more strongly preferred only among right-wing voters. It is unclear to date if this finding reflects a more fundamental and permanent blurring of a social democratic programmatic profile, or if it reflects a temporary uncertainty about the position and direction the social democratic party is going to follow in the future.

9.5 Conclusions

This chapter’s key contribution is to empirically test the appeal of four ideal-typical social democratic programs. Using a survey vignette design implemented in six countries, we provide new and innovative evidence on the social democratic party profiles that voters find attractive. A first key finding is that Old and New Left party profiles are the most popular profiles among potential social democratic voters. Ideologically, potential social democratic voters are located left of the center, with economically and culturally progressive views. Across the electorate as a whole, Left National and Centrist Left programs are more popular, but we argue and show that the overall popularity of these more conservative programmatic strategies may be less relevant for strategic decisions of social democratic parties, because social democratic parties are outside the “consideration sets” of most conservative voters anyways (both economically and socioculturally). We underline this finding by showing that right-wing voters are generally less responsive to targeted social democratic appeals, that is, a Centrist Left or Left National program does not increase the chances of these voters actually choosing social democratic parties over moderate right or radical right parties. By contrast, we find that New Left and Old Left programs indeed make a difference among left-wing voters’ choice, also compared to radical left or green left programs. Importantly, we find several consistent pieces of evidence that show that economically left-wing voters also strongly support culturally progressive programmatic appeals and vice versa.

These results point to several important lessons. First, the electoral potential of social democratic parties is on the economic and cultural left, rather than only on the economic left. Relatedly, presenting New or Old Left programs creates significant potential for appealing to voters within the electoral potential, while Centrist Left strategies seem largely ineffective, and Left National strategies even seem to generate strong trade-offs or negative payoffs: They are likely to alienate more voters on the cultural and economic left than they newly attract to social democratic parties from the cultural or economic right. Overall, what stands out is the appeal of New and Old Left programs over Centrist Left or Left National alternatives. This also means that there is no apparent trade-off between New and Old Left programmatic options: Both economically and culturally progressive attitudes clearly predict support for both Old and New Left strategies.

One unique aspect of our results is that we can present findings for six countries. While the findings as summarized above broadly hold across these six contexts, it is clear that some countries – here, Austria, Switzerland, and Sweden – show a stronger connection between economic and cultural positioning, with New Left programs being particularly popular (and polarizing across the entire spectrum). In Germany and Spain, social democratic support is still more traditional (i.e., highest for Old Left appeals), while in Denmark, Centrist Left and Left National programs are comparatively more appealing to potential social democratic voters than in the other countries.

Overall, our chapter has attempted to highlight the benefits of using an experimental approach to study potential voter support for ideal-typical social democratic programs. Our approach underlines the importance of distinguishing between the general popularity of different policy programs and the popularity of these programs among voters who might conceivably vote for the Social Democrats. These are distinct groups, and different programs appeal to each. When it comes to vote-seeking strategies, all parties – including social democratic ones – may need to consider which voters they can realistically appeal to and which are essentially out of reach. A second implication of our findings is that the often-cited conflict between economic and cultural goals among Social Democrats (a so-called redistribution vs. recognition trade-off) may be overblown. Instead, what seems most relevant for voter decisions is that Social Democrats pursue a program on the ideological left.