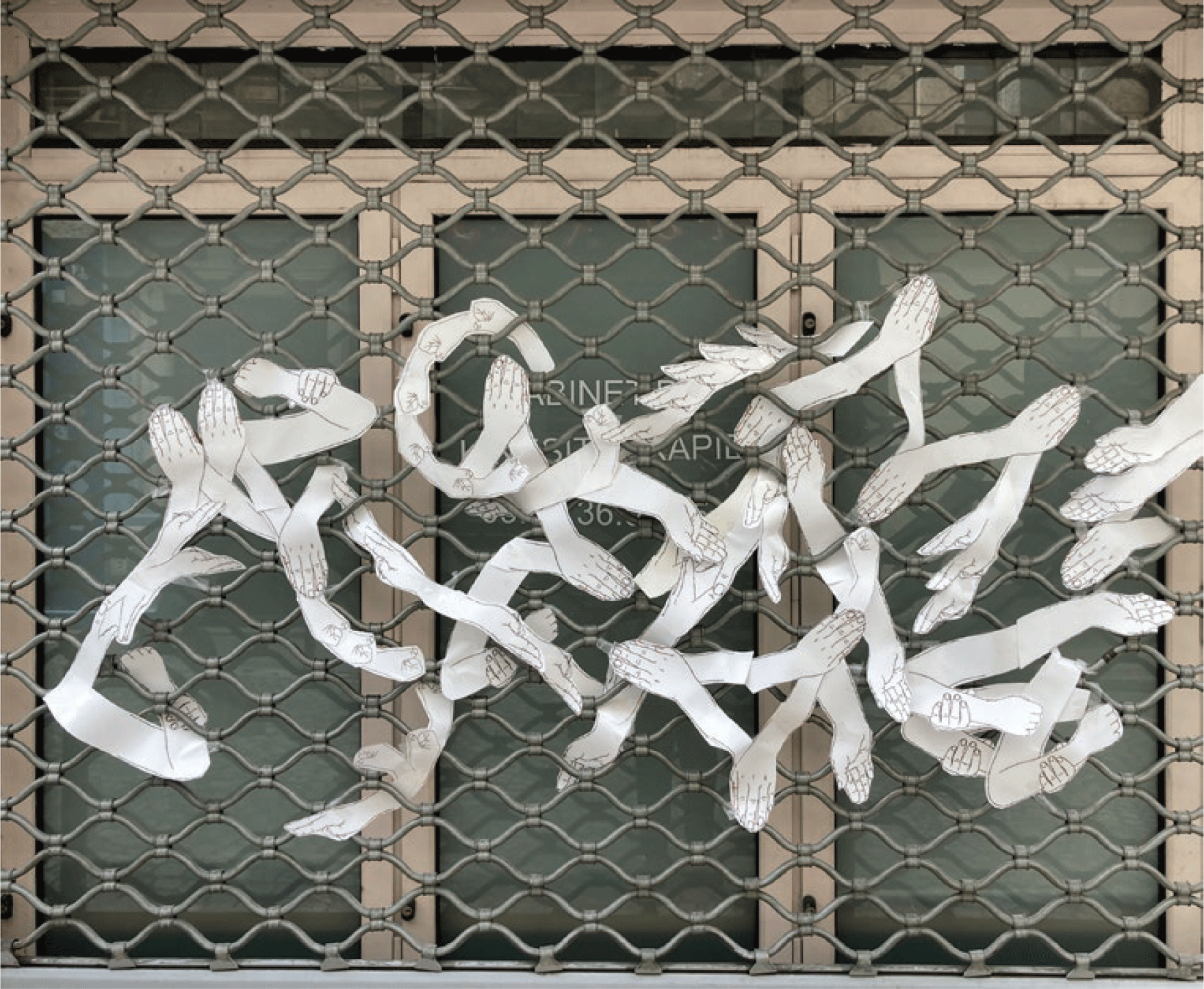

Figure 1. “Restoration” installation on rue Ramey. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

Where is the self in illness? Is it contained in the body when that body is connected to IV drips and chemical infusions, when its borders are breached and the composition of its flesh changes? How does that subject move through a landscape, one that it knew in a previous life but now encounters in a new body? How does the porosity of human perception/memory/emotion meld with its environment in a subtle exchange?

Self-Portrait in Montmartre (2021) is an interactive exhibit of 12 stations by Susan Marie Ossman.Footnote 1 Part of a larger project called Scattered Subjects (2020–2022), it is the second part of a tripartite exhibit, in which participants are asked to walk the neighborhood as they question where they themselves reside and who they are, not only when the body itself is in full transformation, fighting a proliferous internal enemy under the skin, but when the limits of outward movement are determined by the constraints of a global pandemic.Footnote 2 Susan Ossman moves between “creative artist” and “created patient,” between Parisian streets and digital worlds, making the viewers question the very limits of selfhood, providing in the process a very different perspective on the concept of a self–portrait.

In her paintings, moving her brushes forward, her colors floorward and then onto the walls, Susan also moves her artworks outside to the streets. We visit the neighborhood where she lived during the months of the Covid confinement and her own chemotherapy. We travel with her, following the art into public spaces, but also into virtual worlds and other dimensions, through the QR codes that accompany each work. This play of inner and outer skews not only the definition of an artwork and where it resides, but also highlights the constantly transforming canvas of the human imagination.

Susan Ossman is a colorist, in the way that Sonia Delaunay was a colorist. She creates mood with a lithe and vibrant palette, juxtaposing the flowy softness of painted silk with a metal chainlink fence, the fragility of paper cutouts with walls of plaster and concrete. Like Delaunay, she uses fabric and materials from everyday life: poppy seeds, tree leaves, and dried petals. Her painted canvases swirl with blues, pinks, reds, with calligraphy and geometric shapes. Susan calls the overall creation a “self-portrait in Montmartre,” though it also resides in the virtual world.

The “frame” of the work is a one-kilometer circle around the Parisian apartment where she lived from June 2020 through June 2021. There are 12 locations on this map of self-portrayal, 12 months of her stay in Montmartre, 12 treatments of epirubicin and cyclophosphamide, the treatment for breast cancer that entered her veins, making her eyebrows and some of her hair thin and fall out, a shedding of peripheral excrescences. In tracing the dispersal of the elements usually associated with a self, we come back to the self as a shifting locus, a repository of memories, of struggles, of exchanges with others that leave physical traces. Can we ask for more in an era where human subjects disappear into virtual worlds and only remember themselves when their bellies roil in hunger? The hunger that leads Susan Ossman to this scrupulous mapping of the body in pieces, le corps morcelé (the fragmented body),Footnote 3 is in fact the invisible glue to her subjectivity. And there the viewer and listener find substance, placement, a self. The desire to cohere in a world that casts fragments of the self to the wind, to hospitals and pharmacies, to concrete sidewalks, storefronts, fences, parks, cemeteries, and yew trees, is the only stable element.

How to create a self-portrait of a thing as protean as a scattered subject, one that won’t hold still? I am in Paris with Susan to find out.

Paris, one might say, is a city in disintegration. Cities are always in the midst of crumbling. It’s the effect of water on stone, a slow dissolving, as rain leaches into mineral. Such elemental changes in granite and lime are imperceptible to the human eye, attuned as it is to the grosser transformations of detonations, wrecking balls, and war. But water does its work over timespans the human eye can’t perceive, many lifetimes of precipitation. And Paris is nothing if not a wet city. Not quite as much as London perhaps, but the steely chill of the streets of Paris, the drab umbrellas moving like jellyfish above the clay walkways of the Jardin des Plantes towards the Seine, the sounds they make as lovers close them upon entering a bistro and stack them in the holder by the door, these images speak “Paris” more than sun reflecting off the Eiffel Tower. At least to me.

Montmartre is gray and rainy on this March day in 2023 as well. My hotel is down the hill from the Sacré Coeur, that iconic white marble cathedral that dominates Paris, a reminder of its Catholic past, before and between revolutions and existentialism, before the decadence that rose like waves between the wars, before it settled into a staid capitalism well after. A reminder as well of the (failed) attempt by the Commune of Paris to secularize and democratize the city in 1871 (after the Franco-Prussian War), and the construction of the Sacré Coeur church on the very site of the revolt. The stone of the church is travertine, a form of marble that slowly disintegrates, thereby “washing itself clean” after every rain. Nothing is immune to disintegration. Still, life burgeons in the chill of this moist spring day.

Today I will walk again with Susan. We will visit and revisit the stations of her “self-portrait,” the one she created when she was living in a small apartment in this quartier, painting on large canvases that she spread on the floor, while also going regularly to the Hôpital St. Louis for chemotherapy. She didn’t lose all her hair.

“My hair is tough,” she tells me as we walk from my hotel to the first station of her outdoor exhibition. “And I have a lot of it. It did get thinner though. And I lost my eyebrows.”

“I had to take drugs to prepare the body to accept all the poison,” she adds, as she holds open the door of the neighborhood pharmacy. “And other drugs to mitigate the effects. I’m just going to pick up a few things. Do you mind?” Inside, the pharmacists are still wearing masks, but the customers are barefaced. Susan buys a pair of reading glasses. When she goes to pay, I expect the woman and man behind the counter to ask about her health, but they do not. People are waiting. And perhaps they don’t want to be indiscreet. Not everyone goes into remission.

Susan’s diet had to change as well. “Meat is important during chemotherapy treatments,” she tells me, “so you don’t get anemic. But there are also times you lose your appetite altogether. It’s hard to eat when you are nauseous.” I was pregnant twice and know what nausea means. And here we are, in the land of Sartre, his book Nausea ([1938] 1964) back in my hotel room. I bought it soon after Susan spoke to me about her cancer and the nausea the treatment had caused. Sartre originally wanted to call his novel “Melancholy.” That might have been more appropriate, since the existential mood he describes is more about a state of absurdist estrangement from the world than it is about a retching queasiness. But Sartre’s editors changed it. And existentialism will forever be associated with a feeling in the pit of one’s stomach, a bodily impulse indivisible from the mind.

I read Sartre as a student, but it was Being and Nothingness (1943) at that time, not an easy read. I was 21 and enthralled with everything French—Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Proust, and Stendhal; but also the contemporary philosophers—Barthes, Foucault, and the feminists Cixous and Irigaray. Sartre was a lot to take on without a guide. But I did come away with a sense of how religion and culture assign roles to individuals because of their birth, class, or gender, and how these seemingly arbitrary identities go on to determine our place in the world.

And then the sudden realization: in the face of utter meaninglessness, there is nothing to do but write a story with the materials at hand, to turn the en soi to the pour soi, as Sartre might say— circumstance into conscious reflection, existence into narrated experience. This is what Susan has done. She has created an oeuvre from her existential situation, her cancer diagnosis with a world-wide pandemic providing the context, her paint and words their transformation.

Nausea is chemical. Wellbeing is too. The endorphins and hormones released by exercise like walking the stations of Susan’s self-portrait actually change one’s mood. But moods also change one’s body. It’s a feedback loop, which is why Susan had to take drugs to prepare her body for the nausea of chemotherapy and other drugs to counteract that nausea. Cancer treatment is a complicated process of making oneself ill in order to make oneself better, of poisoning the poison in one’s body and somehow convincing the mind that that makes sense. It takes a lot of trust to submit to that. Or is it fear? Or perhaps one just lets go and drops into the cancer treatment machine, turns off one’s mind and follows orders en soi.

Last night the bistro where we ate was animated. A young family with two children sat nearby, an attractive Parisian couple that I might have envied at one time, the parents svelte, the children well-behaved. When my children were their age, I was a single mother, and so, I understand over dinner, was Susan. She brought up her son on her own. Does such a struggle have subsequent consequences for one’s health?

While I have been to Paris many times, this neighborhood is new to me. I am here to learn its shape, its contours, even its taste; here to walk the streets that Susan walked, the one-kilometer square where she and her neighbors were allowed to do their grocery shopping when the world was under lockdown because of the pandemic.

Susan is a dual national. Born in Chicago, brought up in Northern California, in her 20s she married a French man and got her French citizenship. She is the oldest of six children, all daughters. They were not wealthy, but a middle-class American family; her father taught accounting at a state university, her mother was a homemaker who eventually became a buyer and a manager for custom draperies in a department store. They took vacations around the country, all six of the daughters in the back of a station wagon, staying at Holiday Inns.

“Have others in your family had cancer?” I ask when we leave the pharmacy. “Just one so far, a small lump in my sister’s breast. She had a single strong dose of radiation, no chemo. It was a different kind of breast cancer. We were both tested and there is no genetic marker for cancer.” Susan thinks it might have been pollution that caused her cancer, or maybe it was the stress of living with a narcissistic boyfriend for too long. Why does cancer express itself in some and not in others? I have a mammogram scheduled for next month. One in eight women… Susan was diagnosed while visiting her son in Paris. An architect, he had just had his second child. While she might have returned to the United States to be treated (she was a professor of anthropology at the University of California at the time), she decided to do her treatment in France, where she had been a citizen and resident for decades.

When Susan was a recent UC Berkeley graduate back in 1980, she went to Paris to work for the summer. There she met a student who was studying economics. Like her major relationships to follow, he was politically engaged, a militant. They fell in love, had a son, and after a stint in a Brooklyn loft, they returned to Paris where Susan went back to school, this time to do a master’s degree that focused on media and Moroccan writings about how cinema might be reimagined in a postcolonial setting. When she went to Rabat to explore the archives, she realized it would be interesting to meet with those Moroccan revolutionary writers and artists. For the most part, they were still alive. She began to do ethnography, eventually going on to do a PhD in anthropology at the University of California at Berkeley and studying with the theorist and Moroccanist Paul Rabinow.

Over the years, Susan’s relationship with Morocco grew stronger. She became the director of the Institut de la Recherche sur le Maroc Contemporain in Rabat (now called the Centre Jacques Berque). That is where she and I first met, when I was also living in the capital in 1993–94, a Fulbright fellow doing research on trance and translating poetry. “We’ve been following each other’s work for more than 30 years,” I say, as I gather together the lapels of the coat I bought yesterday for 20 euros at the thrift shop by my hotel. “Half a lifetime. A third if we’re lucky.” Susan looks at me and smiles.

“The first station is on rue Ramey,” she says, walking briskly down the street. This is not the type of weather through which one strolls. We are not flaneurs. I struggle to keep up. It is hard to believe that just a year ago Susan was weak and undergoing treatment. But then she stops. “This is where Nat lives,” she says. It is the residence of her son, his partner Jade, and their two young children. Nat and Jade are architects and have converted a storefront into a beautiful apartment, accessible through a door at the back in the garden. A metal grate in the front window can be raised up and down like an electric screen. Here, at the first installation, Susan wove painted silk organza through a chain-link fence, contrasting the soft flow of fabric with galvanized steel (fig. 1). Like flesh on bones, the fragile silk was subject to the vagaries of sun, wind, and rain. She painted it with organic materials—poppy seeds and Moroccan rose petal powder in bright pink—the color of the cancer drugs that zig-zagged through her body, metal and flowers woven together in a double-helix shape. Cancer drugs may damage the DNA, the genetic alphabet she shares with her son and her grandchildren who live on the other side of the pane.

Figure 2. Barcodes for each chemotherapy visit attached to the stairs for “Uphill Battle” on the rue des Saules. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

We continue to walk down rue des Saules, until we reach the second station, a series of stairs between the rue Caulaincourt and the rue St. Vincent, an uphill challenge for anyone, especially a cancer patient. “Here I attached hospital barcodes to the metal banister,” Susan tells me, “just like they were tied to my wrist during treatment, one barcode per treatment.” We make our way up the long flight of cement stairs, and I imagine the red threads attached to the railings, one more each day (fig. 2). Did others stop to look when they saw them, or did they just hurry on? Did they wonder about the meaning of the barcodes and who had placed them there?

“I often went up the steps with the help of my lifelong friend Antonella,” Susan tells me. “I recorded our conversations as we walked.” A soundtrack to their promenade, this recording is now on the installation’s website; a testament to friendship, to mutual aid, to the way we are interconnected like links in a chain. I realize that in a crisis the sound of voices is often as important as what is said. The reassurance of company, the lulling of breath even as it quickens and struggles to keep up, to keep going.

Once I’ve caught my breath we continue to walk down the rue des Saules towards the tourist neighborhood, stopping first on the cobblestone streets between rue Cortot and rue St. Rustique to read the municipal displays that tell the story of van Gogh, with a map of all his travels. “This inspired me to list all the streets where I’ve lived over the years,” says Susan. They are many. Indeed, the number of streets where Susan has lived is dizzying. Lists that span cities, countries, and continents. “The QR code here takes you to this list,” Susan tells me, holding up her phone to my eyes, “but it also takes you to artwork that I have done in each place.” Later, on the website, I’ll see images of Susan’s paintings in vibrant blues, reds, and yellows (fig. 3). The visitor can click on each and move them over the list of street names, creating a composition of one’s own making, a collage with Susan’s art and history as the pieces.

Figure 3. When people arrived at the poster of “Vincent van Gogh, Voyageur” they viewed a list of Ossman’s addresses and images of artworks on their phones. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

Susan has been painting and making art since she was a child. As an adult she has always led a double life—as an artist and as an anthropologist and writer. She has six books, including a memoir called Shifting Worlds, Shaping Fieldwork: A Memoir of Anthropology and Art (2021). I have read them all (1994, 1998, 2002, 2007, 2013, 202l). The topics span aesthetics, migration, media, and culture in Morocco, Egypt, and France. She has access to the right and left sides of her brain. Is one more dominant?

The fourth station confounds the necessity for such a question. It is clear that she is at home in both. We are squarely on the square Place du Tertre, the place where painters sit before their easels doing portraits for money. I had one such charcoal done here when I was 17, visiting Paris for the first time with my host family from the Massif Centrale with whom I had just spent six weeks. I still have the yellowed paper showing a girl with braids wrapped on top of her head, an image of me in 1976, a portrait that, like a photo, captures a moment in time. What moments is Susan capturing with this, her self-portrait in Montmartre? So far there have been no images of her face at the installations. Or was she thinking this to be a creative final act, a last will and testament, an artistic bequeathing to her son, her sisters, her mom? Was she thinking of death as she created this oeuvre in the midst of Covid restrictions and chemotherapy? Or was she confident that she would survive? I don’t pose the question.

At the Place du Tertre, station number five, Susan’s face finally appears as the subject of her own performance art (fig. 4). The task was this: she handed out photocopies of the outline of her face without hair to the few passersby and people she had invited to the exhibition. She asked them to complete the picture with crayons and pens. One person drew a series of lines that connected her image to what looks like computer circuitry. This, she titled, Plug-In. In another, a stream of water is flowing out of her mouth. This was titled, Universals and Essentials. Yet another person drew a large mane of hair around Susan’s face, hair she clearly didn’t have. One portrays her with what looks like a sombrero, another in the very large coat she was wearing, a winter hat on her head. These portraits are reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s work—a series of selves in different garb, a performance of variability. Are these “portraits” how others saw Susan? Or is it how they saw themselves? Who makes a self-portrait? The artist or the observer? How malleable is the self? All these portrayals eventually ended up on Susan’s website.

Figure 4. Drawing the artist at the empty Place de Tertre. The plaza is usually packed with artists making portraits of tourists. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

We walk down the hill toward the rue des Abbesse and the Monoprix Beauty Store, where Susan opens the door and I follow her in, happy to get out of the cold. “This is where I bought my makeup,” she tells me, “when my eyebrows fell out. I came here often to get eyeliner, mascara, and eyebrow pencils. I’m going to get some now. Just liner. Thankfully my eyebrows grew back.” The artist’s website shows pictures of a brow-less Susan painting an arc above her lids, and pulling a liquid liner brush from tear duct to temples, a self-portrait in makeup and mirror (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Painting a face. A shot from “Toile Blanche” (“White Canvas”). (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

Leaving Monoprix we head towards the sixth station. “This is where I went to physical therapy,” she says, stopping at 2 rue Germain Pilon. “It is standard treatment to remove a few lymph nodes to be sure that the cancer hasn’t spread. This made my arm and whole right side of the body swell.” Here Susan created multiple cutouts of interlocking arms and hands in positions physical therapists use to massage patients; cutouts that she once again wove in a chain-link grating, this time pulled down over a closed storefront business (fig. 6). Paper fingers clasp around paper wrists, paper palms against other white palms, paper that eventually will disintegrate in the rain, becoming tree mulch on the sidewalk.

Figure 6. “Handiwork” on the grille of Ossman’s physical therapist’s office. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

An accompanying sound recording of Susan’s then 6-year-old granddaughter, Swann, singing “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes” brings the listener back to childhood, scattering the subject across time, but it is also a reminder of one of the reasons that Susan was in Paris at all—to be with the generations to which she gave birth. Does the subject live on in her descendants? Is subjectivity in the genes that remain after we’ve gone? The therapist’s office is across the street from a massage parlor called The Red Kiss; fertility, sexuality, the subject is also scattered in sexual bliss.

We continue to walk, step after step. The subject in motion, the self moving through time and space. We pass a school and hear children’s voices echoing in a courtyard on the other side of a long wall lined with identical barred windows. More metal, more barriers, I think to myself. The self in the pandemic was imprisoned, but the body is also a holding space, and sometimes it feels like torture to be inside. Sometimes, however, constraint is our teacher.

“Children went to school through most of the pandemic in France,” Susan remarks. “So their voices were never silenced. Here on these window bars I hung 12 actual drawings of my face. Each drawing sported a mask” (figs. 7 & 8). Twelve self-portraits, one for each month of the year, one for each chemo infusion. The drawings of Susan’s face in this station (called “Temporary Exhibition?”) are in black and white, but the masks she wears are in different colors: yellow, pink, blue, green/ white, and one in a multicolored pattern. Twelve different masks both hiding and protecting. Is the exhibit temporary? Is Covid? Is she?

Figure 7. Part of “Temporary Exhibition?” displayed on the windows of a school on rue Durantin. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

We walk on and get to 77 rue Lamarck where Susan stops in front of a bookstore called Librairie L’Eternel Retour, the Eternal Return. “A beautiful name for a bookstore” I note. “I edited my last book, the memoir you read, while I was going through all of this,” Susan says as we look at the books on display in the window. In fact, I have not only read Susan’s last book, but I read it before it was published. “In Shifting Worlds, Shaping Fieldwork: A Memoir of Anthropology and Art,” I wrote then in what was a review for the press, “Susan Ossman creates a new genre: a memoir of herself as artist, anthropologist and serial migrant, whose homes are not only shifting, but whose habitation is the creating body itself” (Kapchan Reference Kapchan2019).

Like Susan, I have often thought that my body is my only home. I, too, have migrated, lived in languages not my own. Yet the home of the body is unsettled when it is sick. It becomes something different, not a refuge but an enemy, an interlocutor and an object against which to struggle.

But is that not what we do all our lives? Battle with entropy, illness, ennui? The existential nausea that so plagued Sartre? Yet, the prolificness of Susan’s life and oeuvre is stunning. Since I met her in 1993 she has published books, performed with her Moving Matters Traveling Workshop in museums like the Hermitage in Amsterdam, and shown her art in galleries across Europe and the US. She always has several projects percolating at any given time.

“In the rises and falls of the music of her prose, we also find the story of a life lived between anthropology and art-making, between thought and feeling, theory and method,” I wrote in the same unpublished evaluation of her work.

Susan works with substances at hand; she composes with tea, for example; she paints with coffee; she sculpts with silk, adding objects from her life and the lives of others, a commentary on the passage of time, on the process of the artist-anthropologist. Her oeuvre is a meditation on fieldwork in the largest sense of the word. […] Susan has the gift of the writer, paired with the creative talent of a painter and colorist. Her beautifully written memoir opens the halls of stuffy academia and breathes new life into many fields. (Kapchan Reference Kapchan2019)

Figure 8. Portion of “Temporary Exhibition?” in the gallery of the American University of Paris. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

Here in Montmartre I am amazed once again at how even under the duress of chemotherapy, even with the restrictions of the Covid quarantine, Susan has managed to make beauty out of necessity, to transform hardship into meaning. The QR code at this site, station eight, “Gather Words,” brings the viewer to a series of beautiful paintings in which Susan pastes pieces of text. They are collages, mixing color and narrative, moment and chronology of time, depth, paradigm, syntagm. These paintings are now on the exhibit website and the viewer can actually leaf through the pages, moving images and page proofs around on the screen with the computer mouse. The self in interaction. A coconstructed portrait, a collaborative project, a life made by one but with others as well.

We walk on, and come back to the pharmacy we passed when we started. The station is nine and it is called “Intoxications.” As someone who has had intimate history with people with addictions, I understand what inebriety is. But the drug that Susan invokes here is the one made from the yew tree, a poison used to kill the cancer in her body. Yew trees, called If in French, are known in Europe as the trees of the dead and are found in cemeteries throughout the continent. Susan plays on the ironies of poison and cure. The paintings that correspond with this station are vibrant swirls of color, as if infused into the viewer’s very being through the eye (figs. 9 & 10). If. Yew. But also and if…

Figure 9. Knotting, 2021. Ink, charcoal, paper, and acrylic on canvas. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

Figure 10. Intoxications, 2021. Acrylic and charcoal on canvas. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

And if the poison poisons, and if the yew doesn’t perform, and if something changes. We live in the subjunctive tense all the time, without cognizance. Trees are poems, and we hang in the balance like leaves on branches that eventually fall.

We walk to ten. Susan points to a balcony above us. It’s a corner apartment that looks over four streets, a crossroads, a carrefour (fig. 11). “This is where I lived during my treatments,” she says. She asks me to listen to a recording she made and holds her phone to my ear. “This station is called ‘Merci pour la Musique,’ Thank You for the Music.” I listen to the famous “An die Musik” leider by Schubert but the beautiful aria is quickly pierced by the sound of jackhammers and construction. I wince. “They were renovating a large building down the street” Susan explains. “And of course everyone was quarantined inside at the time. We all existed between the silence of confinement and pistons; drill bits resonating at 1,800 strikes a minute.” I could feel it in my jaws even in the recording. What must she have felt in her yew-infused bones and limbs at the time?

Figure 11. Music and the sound of construction are combined with photographs on the web page viewers opened when they looked up at Ossman’s apartment from the rue Marcadet. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

No music without noise, no order without chaos, no health without illness. A continual back and forth. And the waiting between beats of the hammer of the heart.

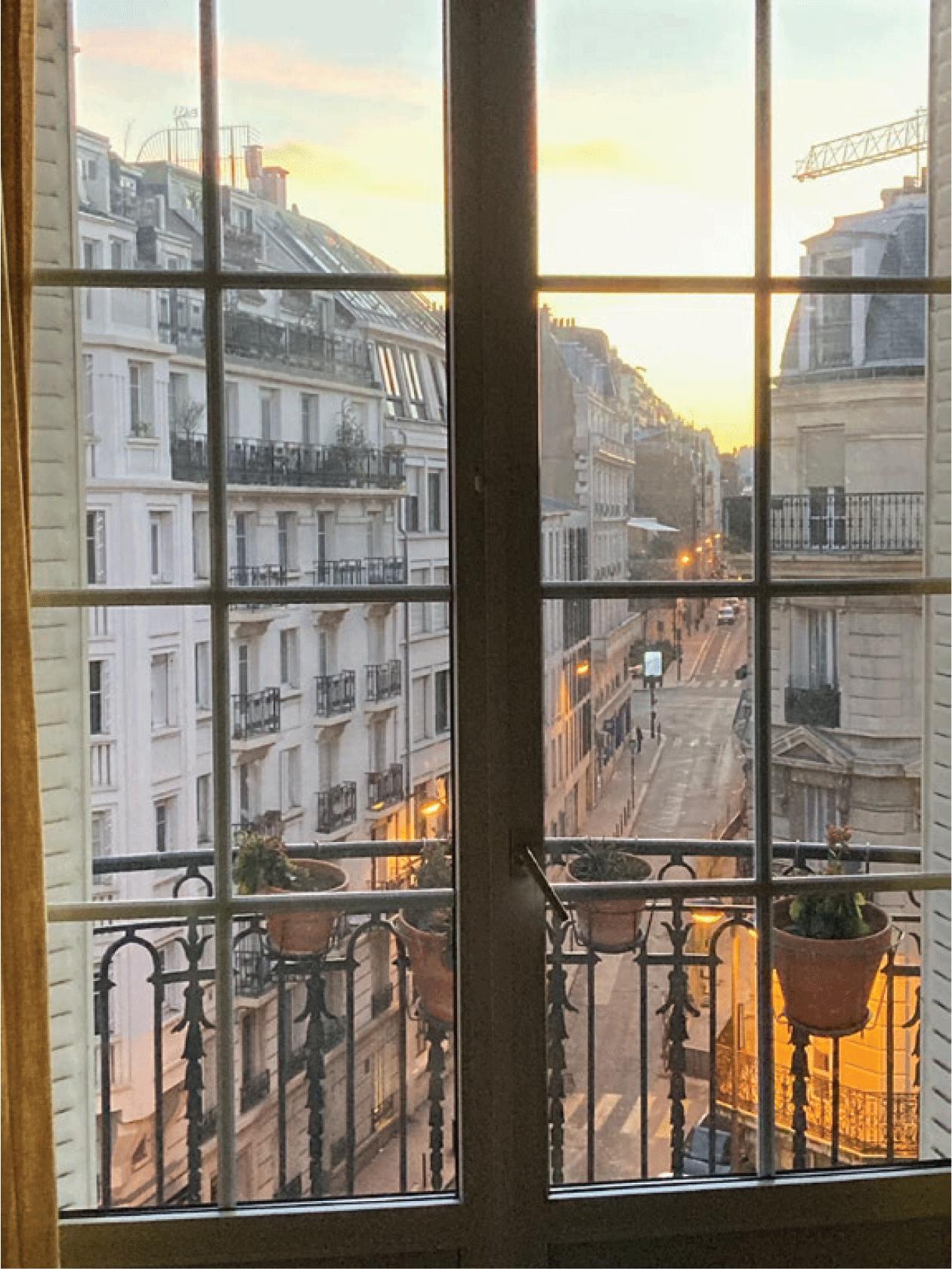

“Station eleven is also here at 204 rue Marcadet, but it’s inside the apartment. There’s someone else living there now, so we can’t go in.” Called “Interiors,” station eleven is an interspersion of images—the apartment (bathroom, desk, working kitchen, French doors opening onto other windows, other black metal balconies across the way). And paintings. Always more paintings. One, in particular, evokes a black-edged ribbon flowing like an inverted infinity symbol on the rim of a charcoal wash edging an orange horizon rising above it like a wave. The entire painting is pulsing movement; dark earth, luminous ether, willowing an untethered band of tremulous life (fig. 12).

I shiver. We have been standing here for several minutes and the wind blows cold.

“My son Nat’s office is just down the street,” Susan says. “We are very close, so it was good to be near his office. I saw him every day when I was going through all of this.”

“You’re lucky to have such a devoted son.” She nods. We walk down the block, stopping in front of another building. “This is the last station, number twelve,” Susan says. It’s called “Next” and stands alone. No QR code. No paintings accompany it. Just paper cutouts of a woman diving backwards from a diving board into a pool painted on a rolling metal door (fig. 13). The cutouts display different placements of the diver moving through the air, her back arched, going up and then over in a half circle before slicing into the water. Susan has pasted these cutouts on an iron curtain, like the one between the West and the Soviet Bloc before 1989, like the often impenetrable barrier between the ego and the unconscious. Diving backwards against the backdrop of an iron curtain, not seeing where you are going, but leaping nonetheless, a fragile self, like paper against the enormity of the social and political world, leaping not to death, but with studied grace into the waters of the unknown.

Figure 12. Interiors #1, 2020. Charcoal and acrylic on canvas. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

I return to my hotel alone to take notes. My room is modest but clean. Most of all, it is quiet, facing the back courtyards of residential buildings in the neighborhood. The heat is still on in March, and the sun is now setting. I lean against the backboard of the bed and open my computer. Though I am tired from a day of walking, my mind is clear. What is it about consciousness that must portray itself, whether in writing, in painting, or simply in the reflection of another’s gaze?

Figure 13. Next, 2021. Vinyl figures on the storefront of the architecture office of Ossman’s son, rue Marcadet. (Photo courtesy of Susan Ossman)

I get up to close the curtains, then return to the bed and pick up Sartre from the night table:

And suddenly the “I” pales, pales and fades out. Lucid, forlorn, consciousness is walled up. It perpetuates itself. Nobody lives there anymore. A little while ago someone said, “me,” said “my consciousness.” Who? Outside there were streets alive with known smells and colors. Now nothing is left but anonymous walls, anonymous consciousness. That is what there is, walls, and between the walls a small transparency, alive and impersonal. Consciousness exists as a tree, as a blade of grass. It slumbers, it grows bored. Small fugitive presences populate it like birds in the branches, populate it and disappear. Consciousness forgotten, forsaken between these walls, under this gray sky. And here is the sense of its existence. It is conscious of being superfluous. It dilutes, scatters itself, tries to lose itself on the brown wall, along the lamppost or down there in the evening mist, but it never forgets itself. That is its lot. (Sartre [Reference Sartre1938] 1964:170)

Scattered subjects. Art on walls, some metal, some concrete, some cellular, others digital. Consciousness, like a yew tree, offering poison to heal. Never forgetting. That is our lot.

In Scattered Subjects: Self Portrait in Montmartre, Susan’s work challenges the limits of what we conceive as a self-portrait. Like the oeuvre of Marina Abramović, the viewer is asked to question not only the self/other threshold but the way the very limits of the body—the skin, the hair, the eyebrows—transform under duress. Susan gives the portrait to others to transform, and although given only crayons (and not things like knives, guns, and a bullet, as Abramović did), there is a coconstruction of a self that is always in the process of its own transformation. Susan asserts her life in the face of its disintegration, its being stolen away not into dust but into cellular proliferation. And she has won. She is now cancer free. The yew tree has killed the cancer but not her body. Now only her paintings proliferate. They line the walls of her studio, each a particular frame of the back dive that is a life, like the click of a camera that captures the flex of a muscle or a twitch of an eye. And while Covid has not disappeared, there is, for now, no more quarantine. Our bodies can move through space, though violence is erupting like pestilence all around.

“It was like the war,” one older French woman told me, speaking of that year of Covid fear, sickness, and immobility. “Curfews and shortages, and papers needed to leave your neighborhood.” Though instead of papers it was an app on one’s phone.

“Who remembers me?” Sartre asks in La Nausée.

Should Susan ask this question, many would answer, “I do.” Her artwork is her memory, and ours, should we embrace it. And when we do, we make her world of color, beauty, and courage our own. Her self-portrait is collaborative, and her uniqueness is her ability to show us that cocreation is also self-revelation.