Death from starvation, although “rational” (caused by eating only one’s rations), is the worst kind of death.

From the beginning of the occupation of Poland and the institution of food rationing, the Germans authorities exerted some control over food access. However, with the establishment of the ghettos, the mechanisms for increased regulation of food supply to the interned Jews by the German authorities were installed. The management of food supply into the ghetto varied over time and place, but ultimately, each of the three ghettos under consideration was closed off from the external food supply. For those ghettos that remained open longer, were more porous, or were granted flexibility in their food procurement, food supply in the ghetto tended to be better. For those where the German authorities determined how much food entered the ghetto – and eventually that was all of them – hunger was rampant.

In Warsaw, Łódź, and Kraków, the Jewish leadership was given some autonomy to distribute the officially procured food. The Jews of the ghetto initially experimented with various means of distributing food, but the Germans eventually took over control of food entering the ghetto and gained an increasingly greater hold on the distribution of food within it. Ultimately, German authorities in all three ghettos dictated food access and distribution. During the earlier stages of ghettoization, the changing porousness of the ghettos, the changing priorities of German authorities, and the decreasing autonomy given to Jewish leadership, as well as the prewar attributes of the specific cities, affected how food was distributed within the various ghettos.

The Warsaw, Łódź, and Kraków ghettos all initially had private shops and restaurants that purchased food through official food distribution networks and from smugglers and sold it to ghetto inhabitants. There were also ration coupons for food distribution, meals distributed at workplaces, and soup kitchens run by organizations and the official ghetto administration. Warsaw and Łódź both experimented with using housing committees for food distribution. Ultimately, in Łódź, there was an attempt to give a minimum food ration to all ghetto inhabitants, while in Warsaw and Kraków, the private market dominated. Although various alternative means of food distribution, including the black market, existed in the ghetto, this chapter focuses on licit distribution to the general population.

Food Distribution in the Łódź Ghetto

When the Łódź ghetto was sealed, the Jewish community became the sole purchaser of food for the ghetto, and the majority of residents purchased their food at private shops and bakeries in the ghetto, which were supplied by the Department of Food Supply of the Jewish ghetto administration. The food for the ghetto had to be paid for in advance to the German ghetto administration (Gettoverwaltung) or to its Department of Food Supply and Economics (Ernährungs- und Wirtschaftsamt), headed by Hans Biebow. There was a tax on the food purchased by the German ghetto administration of approximately 20 percent.

To raise the funds for the initial purchase of food, the private food stores and bakeries supplied cash deposits. As Jakub Poznanski recorded in his ghetto diary, “every person willing to open a store was to pay between a few hundred and a few thousand marks, supposedly as a down payment for provisions: flour, meat, sugar, groats, peas[?], etc. In reality, however, these were deposits that were to serve as floating capital for the Community.”2 Soon after their establishment, the private food shops were accused by the Jewish ghetto administration of taking advantage of their monopoly on food.3 It is not uncommon in food shortage situations for food sellers to use various tactics to maximize their profits on foodstuffs in short supply. Using less flour in bread was a common method to stretch the amount of food available. An order in May 1940 that bread loaves must weigh a full two kilograms indicates that bakers may have been shorting the weight of the loaves (the Warsaw ghetto also had a commission that checked the weight of bread loaves).4 Private stores inflated their prices, and butchers sold inferior meat at set prices while selling the choicest meat at very high prices. A similar practice was also in use during World War I, when shopkeepers in imperial Russia were accused of denying having food in stock and then selling it to the well-to-do at exorbitant prices.5

At the end of May, only one month into the ghetto’s sealing, a new form of food distribution was devised. Food was to be distributed through the house committees, with money for rations collected before the food distribution. The first collection of funds for the food ration was announced on May 25, 1940, for distribution in June 1940.6 That summer, the sale and distribution of food items through house committees ran concurrently with distribution through private restaurants and shops. Distribution franchises with fixed prices for food items were manned by prewar food professionals – former vegetable producers distributing vegetables, and former butchers distributing meat. There were also community bakeries and private bakeries. However, that summer, the ghetto population began starving.7

Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski blamed this starvation on speculation and battled price gouging by various means. Diarist Poznanski, in contrast, attributed the starvation to a lack of funds on the part of the ghetto population.8 The German authorities had purposely set up a system of food purchase by the ghetto whereby the ghetto population, without wide-scale employment, had to pay for their foodstuffs. This was a means of drawing out the valuables of the Jews, which were believed to be hidden in the ghetto.9

The high percentage of the population that could not purchase food led to rioting in August 1940, but even this did not end the Nazi administration’s attempt to leverage food to extract wealth from the ghetto. In September, the Nazis stopped food deliveries to the ghetto for several days to see whether this produced more of the valuables that the German authorities believed to be hidden by the incarcerated Jews. The ghetto dwellers, however, had run out of goods, money, and valuables and, without income, were unable to purchase food. This is supported by the fact that in August 1940, only 52.2 percent of the ghetto population purchased the food rations. By comparison, in October 1940 – after a system of relief had been created to provide money for the unemployed to purchase foodstuffs – 96.7 percent of the ghetto population purchased food rations.10

By the end of 1940, there were again a series of changes instituted in food distribution, with bread and food ration cards issued in December. The cards were distributed on December 15, 1940, and by December 30 food distribution through house committees had ended and food was being obtained with the newly distributed ration cards. At the same time, the Judenrat took over the running of soup kitchens, claiming that the existing ones were unsanitary.11 The Department of Soup Kitchens supervised the five central (formerly “community”) kitchens, the committee-run kitchens, the twelve social kitchens, and private places to eat. Some of the kitchens took ration cards, while others allowed patrons to pay out of pocket. The community kitchens that required ration cards served 15,000 meals. The community kitchens that allowed people to pay out of pocket, conversely, served 145,000 meals. The meals served at the soup kitchens resulted in a new vocabulary. Kleik (gruel) was a potato and vegetable soup, while chlapus (swill soup) was a thin, watery soup with potatoes and noodles deemed by Łódź ghetto writer Jozef Zelkowicz to be “suitable only for pouring out” – a criticism that was a play on the term chlapus, which derives from the Polish word chlapać, meaning to splash.12

The soup kitchens not only fed people but served a social function as well. Shoemakers, carpenters, and rubber-coat workshops had their own kitchens, as did police and firemen. The community-run kitchens served only one meal per day. Unfortunately, soon after the new means of food distribution was devised, accusations arose of vast corruption around the communal kitchens. Rumkowski, in a speech in December 1941, accused the managers of public kitchens of having profit, rather than food distribution, as their primary goal. He then announced a reform of the public kitchens.13 A few months later, in February 1942, Rumkowski announced the dissolution of collective communal kitchens.14 The stated reason was that these kitchens served the worst meals, but the move might have been a tactic to bring food distribution more firmly under the control of the ghetto administration during a period when deportations were taking place.

In January 1941, the Judenrat’s Department of Food Supply was reorganized under the leadership of Zygmunt Reingold and Mendel Szczesliwy. The goal was to decentralize certain sections in order to improve efficiency in food distribution. At the same time, there was an increase in relief allowances for the month of January 1941.15 As part of this overhaul of the food distribution system, five bakeries went into operation on January 20, 1941. Four days later, bread rations for the general population were increased to 400 grams (or 40 decagrams) per day, but supplemental bread rations for workers were discontinued.16 On April 19, 1941, Rumkowski established a new, streamlined form of bread distribution, ordering that it be distributed in consistent five-day portions.17 Thus each person received a two-kilogram loaf of bread for five days, reducing the ability of bread distributors to give out unequal portions.

During that same period, in May 1941, the ration for workers was 479 grams of flour, 18 grams of fat, 60 grams of meat, 36 grams of cereal products, 750 grams of potatoes, 9 grams of coffee substitute, 450 grams of vegetables, 10 grams of sugar, and 7.5 grams of artificial honey. By contrast, the average nonworking person during the same period was entitled to 271 grams of flour, 9 grams of fat, 32 grams of meat, 36 grams of cereal products, 750 grams of potatoes, 9 grams of coffee substitute, 450 grams of vegetables, 10 grams of sugar, and 7.5 grams of artificial honey per day.18 Since potato and meat deliveries to the ghetto were well below what was officially allotted, it is doubtful that this ration was met. In reality, in May 1941, an average of only 286 grams of flour, 19.5 grams of meat, 31 grams of cereals, and 218 grams of potatoes per person per day was ordered.19 The result was that the average number of calories – if food arrived in edible condition and was distributed perfectly equally – came to 1,161 calories per person per day.20 Israel Tabaksblatt estimated that working Jews got approximately 1,000 to 1,200 calories a day.21

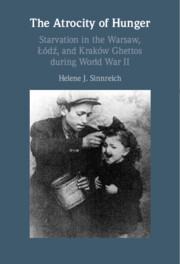

Figure 3.1 Jewish teenage boys push and pull a wagon loaded with bread in the Łódź ghetto.

In September 1941, the daily bread ration was reduced from 40 decagrams to 33 decagrams; thus, a loaf of bread previously designated for five days had to last six days. Very soon afterward, in November 1941, the bread ration was further reduced, this time to 28 decagrams. The cause of the decrease was the influx of new arrivals from Western Europe.22 During the “first five weeks following the arrival of the transports from the west, the Germans did not increase food allocations to the ghetto. Consequently, the same food supply was to sustain a population which had increased by 20 percent.”23

In addition to the reduction in bread rations, other types of food rations were also reduced. A diarist known as Esther/Minia noted on February 24, 1942, that the food ration was meant to last two weeks. She records it as consisting of “one and a half kilograms of beets, half a kilogram of sauerkraut, 10 decagrams of vegetable salad, 60 decagrams of flour, 20 decagrams of farfel, 15 decagrams of margarine, half a kilogram of sugar, and 10 decagrams of grain coffee.”24 These rations were not sufficient; as one survivor explained, “the rations were issued every fourteen days and no matter how careful we were in using them, they did not and could not last longer than ten days. Yet there were the four remaining days, four days of hunger and starvation, four days of tears and trauma.”25

Not every person in the ghetto received their full ration distribution. This is because more food was promised than was actually delivered to the ghetto. For example, during the entire month of November 1941, 32,000 kilograms of sugar entered the Łódź ghetto.26 The following month, the ghetto inhabitants (who numbered 163,623 at the time) were promised a monthly ration of 200 grams of sugar. However, 32,000 kilograms – provided that it was all distributed to the ghetto population with no waste and no theft – would have supplied only 160,000 individuals with their ration. Zelkowicz, reporting in July 1943, wrote of the difficulties connected with the vegetable distribution, whereby “distribution point 1 which has 1,500 customers, has received 600 kilograms of carrots with the order to distribute half a kilogram per head.”27 This left a shortage of 300 rations making it impossible for each person to receive the ration. As a result, Zelkowicz noted, only those involved in the distribution process and their friends were guaranteed to receive the ration, whereas the remainder of the population was forced to push and shove in hopes of receiving a ration before an item ran out.28 To compensate for the lack of food, the distributors reduced the weight of the items being distributed. This did not go unnoticed by the population. As one diarist wrote, “There’s some weight missing in all the products issued at the grocery cooperatives: there’s 3 decagrams missing in every 30 decagram portion of sugar and 10 decagrams missing in every 1 kg of vegetables. And yet no one intervenes! Everybody is scared, and just as well!”29

When a ration was received by the ghetto consumer, it was often in poor condition. An anonymous girl, writing in her diary in March of 1942, noted, “In the morning I stopped at the vegetable cooperative. They give three kilograms of beets for one ration card. But can you call them beets? They’re just manure. They stink and evaporate, and what’s more, they have been frozen a few times.”30 It was not just vegetables that arrived spoiled, Hersz Fogel noted in his diary in the summer of 1942: “the rationed sugar and flour are spoiled, flour comes in lumps, the sugar is damp and it’s difficult to break it apart!”31

During 1941, food in the ghetto was still dispensed by the Jewish ghetto administration, which tried to cater to a variety of food interests and religious traditions. For the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, the bakeries of the ghetto accepted cholent (Sabbath stew) for baking.32 Earlier that year, for Passover, matzah was baked and offered as an option instead of the bread ration. Additionally, three kosher soup kitchens were opened during Passover to distribute meals.33 Passover meals served at the kosher kitchens, which consisted of two dishes, were sold for thirty pfennigs. Rumkowski allocated 30,000 marks to make relief payments and to purchase holiday allotments. However, a food shortage in early April 1941 was reflected in a meager food allocation for the Passover holidays, which resulted in high black-market prices for food.34

Rumkowski attempted to allocate better rations for holiday weeks. For example, there was an increased food allotment for the holiday of Shavuot. For the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, children aged two to seven were given extra food portions and thicker soups.35 Religious traditions were also taken into account when dealing with difficult questions connected to food. For example, a rabbinical decision was issued that allowed pregnant women and the sick to eat nonkosher food.36

The Jewish ghetto administration did not retain control of the internal food distribution in the ghetto for the entirety of the ghetto period. In September 1942, the ghetto leader had a breakdown following the deportations of children, elderly, and the sick. At that point, Hans Biebow, the German ghetto administrator, took more direct control of the ghetto. He empowered a special unit of the ghetto police under the supervision of David Gertler (and later, Marek Kligier) to distribute food, among other functions.37 An extensive system of supplemental food coupons arose (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 Daily rations of bread and horsemeat in the Lodz Ghetto41

Food Item | August 20, 1940 | November 2, 1940 | April 2, 1942 | December 15, 1943 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Bread | 500 g | 300 g | 321 g | 350 g |

Horsemeat | 50g. | 22 g. | 14 g. | 35.7 |

In October 1943, Biebow announced that he would personally take over the distribution of food due to corruption.38 One month later, numerous supplemental foods were canceled, including supplemental soups and special rations for privileged groups such as ghetto administrators. Instead, supplemental foods were offered as a reward for workers, with the top 10 percent of workers, for example, being offered supplemental soups.39 By January 1944, Biebow was so directly in charge of the food policy that he was even signing the food distribution lists.40

Provisioning the Kraków Ghetto and Food Distribution

Unlike with the Warsaw ghetto and the Łódź ghetto, very little documentation from the Kraków ghetto – including both the internal Jewish administration and the German administration – survived the war. The provisioning and distribution of food in the Kraków ghetto must be largely reconstructed from survivor testimony. Based on such accounts, it appears that the food situation in the Kraków ghetto was better than in many other ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe.42 A number of factors have likely contributed to this state of affairs (or at least to its perception). The first factor might be that because few wartime testimonies exist, testimony from the Kraków ghetto mainly comes from survivors, speaking in hindsight about a ghetto experience that predated time in Płaszów or Auschwitz concentration camps, compared to which the ghetto must have seemed not so bad. Further, postwar testimony by its very nature reflects the reality only of those who were able to find sufficient food to survive in the ghetto. Those individuals who faced the worst conditions did not survive to provide postwar testimony. Finally, the Kraków ghetto dwellers were as a whole an elite group, whose experiences may very well have been qualitatively better than others in the ghettos.

Unlike many other ghettos under Nazi occupation, which accepted all Jews living in the city and often the surrounding area, the Kraków ghetto was largely limited to Jews who had been granted special permission to remain in Kraków. Only about 25 percent or less of Kraków’s prewar Jewish population was allowed to settle into the ghetto. Applications for entry included questions about employment, sources of income, and health. This meant that the Kraków ghetto generally comprised individuals in the upper class and people with work permits rather than large numbers of the poor or unemployed. Even so, hunger was certainly present in the Kraków ghetto, for some from the very beginning, and for others as they were increasingly impoverished due to selling off possessions to supplement their rations.

Halina Nelken’s earliest diary entries about life in the Kraków ghetto relate her family’s hunger:

I don’t want it. I don’t want it. I don’t want my empty stomach to growl, our room to be freezing cold, and my father to be so tired, to be so terribly skinny after the last few days that his skin hangs on his bones. I don’t want Mama looking gaunt, and all of us constantly hungry, cold, disheartened, and bitter. God, what can I do about it? There really is no way out of our situation. There is no way out. We are without money, without provisions, without hope of getting any appropriate paying job. And what good can my miserable salary do? It barely covers my small needs, and how could that laughably small wage of mine cover the mass of small debts and help us to live?43

At the time Halina was writing, the Nelkens had not been able to work in their prewar jobs since the German invasion and had not yet secured positions in the ghetto that would allow them to survive. They already depleted their savings during the period of German occupation that preceded the ghetto.44 They were able to run a debt at the bakery, which allowed the family to get by. Nelken’s father would later get a good position in the ghetto, but even so (and even with other family members also holding jobs), they needed to continue selling off possessions in order to feed the family. Nelken related that she prepared the family’s meal when her mother was sick: potato soup and noodles with beet marmalade for the main course.45 As their circumstances continued to deteriorate, the family turned to obtaining meals from a soup kitchen, the “Kitchen for the Intelligentsia.” Nelken describes a meal of “rutabaga and half rotten potatoes with mustard gravy” from this kitchen that, in her opinion, was worse than the food at the prewar “Brothers Albert shelter for the homeless.”46 Eventually the Nelken family’s situation improved, however, and the family was no longer reliant on soup kitchen meals.

Food distribution in the Kraków ghetto was based on a ration card system that allowed the purchase of items at food shops in the ghetto. Kraków ghetto survivor Norbert Schlang describes the family ration card as a yellow card that was replaced monthly.47 Food rations were only available to those who were officially registered as residents. At various points in the ghetto’s history – connected with mass deportations – the Kennkarte (identity cards) of Jews in the ghetto became invalid, requiring an appearance before officials to obtain new documents or stamps for the old identification papers.

The food in the shops that could be purchased with ration cards was not terribly expensive but was not sufficient to meet the needs of Kraków ghetto inmates.48 Aleksander Bieberstein lamented that ghetto residents were limited to 100 grams of bread per day and a small monthly allotment of sugar and fats.49 The bread was described as not particularly appealing. Additionally, stores did not always have in stock the rations promised on the ration cards, which might have been due to undersupply by the Germans or illicit diversion of the food to private buyers. This led to people queuing to make food purchases on a daily basis. Nelken in her diary notes that each day a family member left first thing in the morning to stand in line for bread or margarine.50 In addition to purchasing food at stores, many individuals received a meal while at work. Those who did not do so brought a lunch or returned home; Nelken rushed home from work to eat a lunch of “potatoes, turnips, carrots sometimes, and so on ad infinitum.”51

Licit food distribution in the Kraków ghetto was not limited to those who could purchase it or those who received it as a benefit of working. The ghetto used a variety of means, such as a public kitchen, to provide food for those who needed it.52 Those who were under communal care such as orphans and the elderly received their meals through various institutions. The poor in the ghetto were served not only by the official Jewish community but also through charitable organizations. For example, CENTOS (Centralne Towarzystwo Opieki nad Sierotami or the Central Association for the Care of Orphans) operated orphanages and other childcare facilities in Kraków that distributed food to their wards. The serving of meals at childcare centers helped motivate children to attend, particularly older children, who might otherwise choose to beg or scavenge for food.

Those of less means were hindered in their search for food not only by the lack of foodstuffs but also by the lack of fuel. If one made a fire for any reason, it was optimal to also use the fire for cooking purposes. Thus, even when Kraków ghetto survivor Nelken burned the furs she had hidden (rather than give them to the Nazis), she used the fire to cook potato soup.53 Another means of cooking food when fuel was scarce was an old practice in Jewish communities: bringing items to be cooked to the communal bakery. There, one handed in their food item uncooked and received a redemption ticket in exchange. Bernard Offen, for example, recalled that his family would bring a cholent to the ghetto bakery so that it could be baked during the Sabbath without the family kindling a fire and thereby desecrating the Sabbath. This prewar practice went on into the ghetto period, though Offen recalled that his family was only able to occasionally use the community bakery for this purpose.54 Even nonreligious Jews in the Warsaw ghetto used the community bakeries to cook Sabbath stew due to the high cost of fuel.55

Some individuals living in poverty in the ghetto spent their time roaming the streets in search of food. Mark Goldfinger recalled searching for potato peels or other food refuse to feed himself.56 Some people begged for food from individuals or families, who sometimes provided food as a form of charity. Adolf Wolfman testified that he was always hungry in the Kraków ghetto and lived off of begging; his neighbors would give him food and money that he used to buy bread.57 Tola Wehrman’s family provided soup for the hungry on Sundays.58 This practice of inviting others to a private home to receive a meal was a method that many families in various ghettos employed to feed those in need and had been commonly utilized to combat food insecurity prior to the war.59 Those who failed to get enough food starved – first swelling up from hunger and then ending up on the horse-drawn wagon that took corpses from the ghetto to be buried.60

In contrast to the various means by which the poor received food in the ghetto, those with the funds to pay were able to obtain food at restaurants, cafés, bakeries, and candy stores. According to Tadeusz Pankiewicz, “new shops, restaurants, bakeries, dairies and eateries kept sprouting up.”61 A restaurant on Lwowska Street, next to the ghetto entrance gate, served “ferfel with black pudding, Jewish-style fish and on Saturdays, cholent.” A café on Limanowski Street was “famous in the ghetto for its exquisite whole bean coffee and delicious home-made cakes.”62 Pankiewicz, a non-Jewish pharmacist who lived in the Kraków ghetto during his time running the pharmacy there, took his meals in a Jewish restaurant that was open right up until the final deportation in March 1943.63 It was not only this non-Jew living in the ghetto who kept the doors of these food sellers open. There were sufficient elites in the ghetto to keep not only bakeries with sweets in business but also even a candy store run by the Wohlfeiler family. The confectionary was supplied with smuggled foods when it ran out of licitly sourced products. One of the products it sold was smuggled-in day-old pastries from a shop on the Aryan side of the city.64

Not only were private food sellers supplied with food through smuggling but also some of the food on the black market came from the licit food supply. Shopkeepers who received items to sell to those with ration cards also sold those items under the counter to people who could pay high prices.65 This diversion of licit or rationed food to the black market is a common practice in places where food is insecure. This occurred in other ghettos and also in other places with food shortages, such as the Russian Empire during the First World War.66

Many in the ghetto supplemented the licit food available by obtaining food from outside the ghetto. This was especially true in the earlier period of the ghetto and was possible because the Kraków ghetto, unlike the Łódź ghetto, was not hermetically sealed. For much of the ghetto’s existence, there was extensive travel between the ghetto and the outside city. Jews were able to enter and exit the ghetto for numerous reasons, predominately related to serving as a labor force in non-Jewish portions of the city. As time went on, however, there were increasing restrictions on movement in and out of the ghetto.

The openness of the Kraków ghetto and the supply of food through sources such as private shops, restaurants, and charitable groups may have been by design. It may have been more efficient to allow the private purchase of food for the Kraków ghetto than to have a provisioning division for such a small enclave. Given the lack of surviving documentation, we cannot be sure why the ghetto developed the way it did. Ultimately, however, the Kraków ghetto became more and more restricted and reliant on the supplies provided through German channels.

The Kraków ghetto went through three major stages of accessibility. The first stage spanned from the creation of the ghetto in March 1941 to the first set of deportations in June 1942. During the first stage, there was relative fluidity between the ghetto and the non-Jewish portion of Kraków, with many individuals able to obtain a pass for work and other reasons. Jews were also able to receive food packages by mail during this period. The Hollander family’s letters from the Kraków ghetto were preserved by their recipient living in the United States, Joseph Hollander, who recounted the items he sent them in various food packages: coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, marmalade, rice, honey, canned sardines, bacon, canned milk, chocolate, canned foods, and soap, among other things. Initially, some of the packages failed to arrive in the ghetto. Joseph’s family there informed him that the most reliable mail route in Europe, for both letters and packages, seemed to be through Lisbon. He then used that method successfully.67

After the June 1942 deportations, it became more difficult for individuals to pass in and out of the ghetto. Work groups, however, were still sent out, and numerous privileged individuals maintained passes that allowed them to enter and exit the ghetto. Additionally, the ghetto was reduced in size following the June deportations, which meant that people had to move out of their existing housing into already crowded apartments within the new ghetto borders. The deportations of October 1942 marked another turning point; restrictions on access to the nonghetto portions of the city were increased. Eventually, in the final months of the ghetto’s existence, it was split into two sections. There were tight restrictions not only on entering and exiting the ghetto but also on passing from one side of the ghetto to the other. Ultimately, the population doomed to be murdered by the Germans was denied all food access.

Provisioning the Ghetto and Distributing Food in the Warsaw Ghetto

Food for official distribution in the Warsaw ghetto was, beginning in January 1941, procured by the Judenrat through the German Transferstelle (transfer office), which opened shortly after the closing of the ghetto on December 1, 1940.68 The Transferstelle regulated trade between the Jewish ghetto and the rest of the city of Warsaw and was supported through a monthly charge paid by the Jewish community that effectively created a surcharge on items entering the ghetto.69

Ration cards were distributed by a residence registration officer based on official, regularly updated lists of ghetto residents. A small amount was charged for the monthly yellow ration card. At various points in the ghetto’s existence, the cost to obtain the ration card increased or fees were tacked on to it, although the poor were exempt from the tax and the added fees.70 Once a person’s residency was confirmed and they obtained a ration card, it had to be registered with a food distribution shop. Official food rations that were available through this means were quite small. The amount allocated per person per day for food purchases in the ghetto was extremely low, only thirteen groszy. Reporting in December 1941, Adam Czerniaków noted that the ghetto legally received 1.8 million zlotys’ worth of food for the month.71 The meager food supply for distribution using the ration system was obtained through orders placed by the Supply Section, headed by Abraham Gepner, with the German-controlled Transferstelle. The Supply Section had to pay for the orders with foreign currency or finished goods.72

Although Jewish communal leadership requested increases in food allotments through the spring and summer of 1941, the German authorities generally turned down these requests with a litany of excuses, or else agreed to them but then left them unfulfilled.73 During that period, Czerniaków requested a food system as in the Kraków ghetto, where “a large part of the population has passes and shops outside the Jewish quarter.” He was told in response that “Kraków is different from Warsaw and that we must carry out the orders of our immediate superiors.”74 Change, however, was forthcoming.

After struggling with high mortality rates due to starvation and an inefficient food supply, the Warsaw ghetto saw provisioning improve in the summer of 1941.75 In July, the Jewish ghetto authorities were given permission to bypass the Tranferstelle and make purchases directly from wholesalers outside the ghetto.76 Additionally, official Jewish ghetto soup kitchens were opened under orders from the German authorities.77 In September 1941, the Supply Section became a separate agency and officially came under the direction of the leader of the Warsaw ghetto, Czerniaków. He, for the remainder of his life, repeatedly proposed food purchasing schemes to the Germans in an attempt to increase food in the ghetto.

Just as in Łódź, the Warsaw ghetto experienced issues with the delivery of ordered items and the quality of food. To get potatoes and other necessities delivered, Czerniaków had to grapple with German officials who were unwilling to recognize the authority of others and thus denied food deliveries.78 The quality of the food provided to ghettos was often quite low. Beniamin Horowitz, a Supply Section worker, reported on a shipment of pickled beets sent at the beginning of the ghetto period: “The pickled beets were moldy and some of the barrels were leaking…. There was no way they could be used.”79 Ultimately, even the free soup kitchen could not use the pickled beets. At another point, the same company that had sold the ghetto the beets used a middleman to sell the ghetto another load of inedible food. This one ended up rotting, not even suitable for animals.

In the Warsaw ghetto, the Judenrat’s Chemical and Bacteriological Institute tested food samples to assess health risks. For example, “from July to October 1941, 166 food samples were tested and 718 bacteriological analyses were carried out.”80 Food shortages in Warsaw were also sometimes caused by food spoilage due to poor food quality or poor food storage. In March 1941, there was a loss of potatoes because the weather had been too mild to keep the buried potatoes preserved through the winter.81 During Passover that year, matzah was available using ration cards, but few other Passover-appropriate foods could be obtained.82 As a result, Emmanuel Ringelblum claimed that “the rabbinate is going to declare various types of beans and gourds kosher for Passover use, out of fear lest there be a shortage of matzah—and the Orthodox go hungry.”83

Once food items were received by the Supply Section, they were either distributed at retail locations to those with ration cards or sent to a processing center for further distribution. Additionally, approximately 10 percent of the ghetto’s food supply was distributed in a variety of institutions in the ghetto including orphanages, hospitals, soup kitchens, and homes for the elderly.

Although the distribution of food was officially under the direction of the Jewish ghetto administration, the German authorities regularly indicated specific groups within the ghetto that were to get supplemental rations. For example, the Jewish police were entitled to large food rations, prisoners in the ghetto’s Jewish detention center were only allocated 4.5 ounces of bread per day, and in one instance, a bonus food ration for Aryan workers came out of the Jewish quarter’s bread allotment. There were some places, though, that Czerniaków had a small amount of discretion; he was given an allotment of food that he could designate personally to recipients.84

Ration cards entitled ghetto inhabitants to a scant number of items. According to Mary Berg, writing on December 15, 1940, in the Warsaw ghetto, “The official food ration cards entitle one to a quarter of a pound of bread a day, one egg a month, and two pounds of vegetable jam (sweetened with saccharine) a month. A pound of potatoes costs one zloty.”85 In November 1941, Czerniaków reported an increase in food rations per person, which included “10½ ounces of sugar per month, 3½ ounces of marmalade a month, 1 egg per month, 220 pounds of potatoes per year. The bread ration is to remain as before: not a chance of increasing it.”86

At various times, the ghetto authorities raised money for food by charging for the bread ration cards. In July 1941 and February 1942, the price of bread cards was increased in the ghetto. In September and October 1941, the official price of bread in the ghetto was 1.20 zloty per kilogram, while sugar was 6 zloty per kilogram. These prices included a surcharge to allow the ghetto to purchase provisions for the winter.87 As a result, in February 1942, there was free bread and sugar distribution to reimburse the population for the surcharges in the fall. At the end of December 1941, the Jewish community raised the official price of bread. A few days later, the German authorities added to this a tax, bringing the price of bread to 90 groszy (0.9 zloty). At the same time, the Germans instituted a division between privileged and standard bread rations.88

In addition to the paltry rations, there were repeated issues with distributors shorting the amount of foodstuffs sold and selling adulterated products. Ultimately, the food rations in the Warsaw ghetto were inadequate for sustaining the population. Most people in the Warsaw ghetto relied on other food sources for survival. These included soup kitchens, food provided at places of work, mail packages, black-market purchases, and smuggling, as well as charity offered through organizations and the official community.

The summer of 1942 and the great deportations that began at the end of July brought a major transformation in the Warsaw ghetto food supply. At the end of July 1942, the soup kitchens were converted into kitchens for workers. Rachel Auerbach, who headed the soup kitchen at 40 Leszno, noted that at this time, the kitchen transitioned from being a privately funded space to being a “shop kitchen” for workers of the German firm W. C. Többens.89 After August 15, 1942 – and a large number of deportations, including the mass deportation or murder of the bulk of the Judenrat officials – the only function of the Judenrat was to supply the ghetto with food. This pattern continued with the Judenrat’s decreasing size until the outbreak of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on April 19, 1943.90

Mail Service and Food Packages

The Warsaw, Kraków, and Łódź ghettos had mail service, at least for some period of their existence, that allowed people to receive packages including food and money.91 Unfortunately, mail service was not always consistent or reliable but was rather marked by periodic requisitioning of packages, mail stoppages, unreliable delivery, and plunder. In Łódź, at one point, Rumkowski began requisitioning food directly from food packages for the poor and sick, while money received had to be exchanged at official rates for ghetto currency, making it worth significantly less than on the black market.

In Warsaw in September 1941, the Germans seized 6000 parcels at the post office. According to Czerniaków, the contents of the parcels were sent to a shop that distributed food and other items to privileged Germans in Warsaw.92 In other cases, food was simply stolen from packages. In many cases, those receiving food by mail had to bribe their post office official to be given the package. For those who did receive their packages, the contents proved important to their overall nutrition. In Kraków, for example, numerous families received coffee and other items in the mail.93 And, writing from Warsaw, Ringelblum noted in February 1941 that “a large number of packages have been arriving from Russia and Yugoslavia lately (2,000 a day). They’re very good: fats, coffee and the like. They are important in feeding the populace.”94 These shipments from the Soviet Union accounted for 80 percent of packages sent to Warsaw.95 In Łódź, roughly 4,500 food parcels per month (half of all parcels sent to the ghetto) came from the East. The number of food packages was greatly reduced with the outbreak of war between Germany and the Soviet Union in June 1941.96

Agricultural Production in the Ghettos

In all three ghettos, attempts were made to supplement food rations by growing food, both by raising livestock and by cultivating plants. Ghetto dwellers used every available bit of space for planting: window sills, balconies, and green patches in front of buildings and in courtyards. Describing these efforts in Łódź, one survivor related, “because of the intense hunger, people began to plant things on rooftops, window sills, backyards. Each vacant spot was used for planting.”97 In Warsaw, dedicated organizations cultivated any arable land in the ghetto, including yards and even the cemetery. Those who engaged in this project were not paid, but they got to keep the harvest.98 In Łódź, those growing produce sometimes sold their crops on the black market.99

Figure 3.2 A group of people gardening in a garden plot in the Łódź ghetto.

In Warsaw and Łódź large gardening plots were available.100 In the Łódź ghetto, these plots and seeds were administered through the ghetto’s Department of Agriculture, which, in March 1941, made 200-square-meter plots available for rent to those without stable incomes.101 However, when vegetable shortages occurred, the Jewish ghetto administration in Łódź expropriated the vegetables from the larger private garden plots. The Department of Agriculture counted plants to keep the private plot gardeners from digging up their vegetables early.102 In the early days in the ghetto, there were also hachsharahs, or communal garden plots, that were farmed by Zionist youth groups in both Łódź and Warsaw, and in Warsaw, the Zionist group was allowed to work fields outside the city.103 Additionally, the Toprol Society planted food and flowers in any available patch in the ghetto. According to Warsaw ghetto diarist Ringelblum, this society planted 200 courtyards.104 Just as some soup kitchens served as clandestine schools or other meeting places, gardens in the Warsaw and Łódź ghettos served as meeting places and even as educational spaces. Chawka Folman, a Warsaw ghetto underground courier, noted that the Zionist youth group Dror utilized the “gardens in the ghetto at 17 Nowolipki Street, 35 Nowolipki Street, and 12 Elektoralna Street” for natural sciences classes for their clandestine gymnasium (secondary school).105 Sometimes small lots of land were used by private individuals. Kraków ghetto survivor Lucy Brent had a small garden and two live chickens in a small plot of land next to her apartment. The garden was lost when the ghetto size was reduced.106 Elites in the Łódź ghetto also benefited from garden plots that grew vegetables just for distribution to them. Those who harvested the vegetables in this garden were able to keep the greens.107

In all three ghettos, private citizens also held livestock, and communally held livestock was used to support the wider community. In Łódź, at the beginning of the ghetto’s existence, there was livestock both in private hands and in the hands of the community.108 Warsaw had a dairy with cows, and the Toprol Society raised chickens. Individuals in both Warsaw and Kraków privately held goats, and as late as July 1942, Czerniaków was making inquiries to the Germans about raising rabbits in the Warsaw ghetto.109 In addition to raising livestock for food, some turned to hunting to supplement available provisions. In Kraków, for example, pigeons were a “hunted” food source.110

Manufacture of Food in the Ghettos

Food processing took place within the walls of all three ghettos. This food processing ranged from individual, home-based preservation of food that arrived in poor condition to large-scale food processing such as manufacturing synthetic honey and baking bread for those inside the ghetto. The most important food manufactured inside the ghetto was bread.

Although baked bread was at times brought into the ghettos, bread was baked inside all three ghettos for their inhabitants, and all three ghettos were the site of numerous complaints about bread quality. Many tied the issue to low-quality flour or adulteration of baking ingredients, perhaps done to enable the skimming of baking products for black-market distribution. The end result, though, was poor-quality bread. Kraków ghetto survivor Nathan Nothman described the bread in the Kraków ghetto as being “like clay.”111 Fogel, writing in his diary at the end of June 1942 in Łódź, noted, “The bread we get is horrible and impossible to eat, we need to dry it first. We have large-scale food poisoning in the ghetto because of the bread.”112 In Warsaw, there were inspections of food processing in the ghetto due to food quality issues.

In addition to bread, all three ghettos produced some sort of sweetener that was distributed to inhabitants. In the Warsaw ghetto, a factory-made marmalade out of “carrots and beets sweetened with saccharine,” and Kraków ghetto survivor Rachel Garfunkel similarly described the ghetto jam as made of red beets and saccharine.113 Ersatz honey was likewise produced in all three ghettos. In Warsaw, as Mary Berg reported, the honey was made out of “yellow-brown molasses.”114 A detailed record of the process for making honey was recorded in the Polish Jewish newspaper Gazeta Żydowska on June 24, 1942: Brown industrial sugar and water were heated in a boiler to 85 degrees Celsius (185 degrees Fahrenheit), at which point “a little hydrochloric acid is added.” The reader was assured, however, that after the two-hour process, the acid was “neutralized, that is, it becomes harmless—it is no longer a threat to health.”115

Some food processing in the ghetto was undertaken to salvage processed foods that arrived there. For example, 10,000 kilograms of rancid, black butter that had been determined by experts to have been sitting for at least six months was delivered to the Łódź ghetto. Rather than throw away the rotten food, the food department used “processing” facilities to wash it and produce a quantity of “relatively clean” butter that could be consumed by the ghetto population, whose “stomachs are accustomed to everything.”116

One of the most creative bits of food production was the Łódź ghetto “salad.” Composed of salvaged edible parts from rotten food shipments, it was served to workers and distributed to inhabitants as well. Rotten vegetables were also often “saved.” Oskar Singer describes how in one workshop, leftover scraps, bread crumbs, and the edible parts of rotten vegetables were saved and made into a salad for ghetto dwellers’ consumption.117 One of the “salad” ingredients was butter (perhaps the same butter that had been “salvaged”?).

It was not only the Jewish ghetto administrations that produced food in the ghetto; numerous individuals engaged in food production. Shimon Huberband, for example, noted that although industrial, ritual slaughter of chickens came to an end in Warsaw with the sealing of the ghetto, ritual slaughterers continued to butcher chickens in their own homes. The chickens were smuggled into the ghetto by children. There were also kosher butchers, who, given the impossibility of smuggling cattle into the ghetto, smuggled themselves out instead. They then ritually slaughtered an animal and smuggled in the butchered meat.118

Additionally, some individuals undertook small-scale commercial food production in their homes, with products ranging from candies made from saccharine to meat patties. In the Warsaw ghetto there was a man, Avrohom Otsap, who with a hand mill would “grind grain for a few groschen.”119 In addition to commercial food production, food preservation and other types of food processing for home use took place in homes in the ghetto. In the Kraków ghetto, Nelken noted, “On Tuesday Mama decided to prepare provisions for winter, so we celebrated the making of sauerkraut. She took command; Mietek and I shredded cabbage with a passion worthy of a better cause, while Papa, looking like an expert, crushed the cabbage with a club in a large pot.”120

Food Lines

Food lines were a regular feature of ghetto life, whether they were to buy basic foodstuffs, procure a meal at a soup kitchen, or gain access to a kitchen in a shared apartment or communal space. Photos, drawings, and even film footage preserve images of this ubiquitous task of standing in line for food in the ghettos.121 The lines were often unbearably long. People might spend hours waiting in line for food rations. One Łódź ghetto policeman recalled showing up for guard duty at 2 a.m. on a cold wintery night only to find a woman already standing in line for the potato distribution the next morning.122

Numerous ghetto writers during and after the war recorded the miseries of the food distribution lines. Łódź ghetto survivor Lucille Eichengreen described how “long lines of hungry ghetto dwellers waited outside the food distribution centers for hours on end before they got their meager rations. Hunger upon hunger was followed by even more hunger.”123 Kraków ghetto survivor Nelken described how, “One of us runs downstairs to line up for bread or maybe even margarine.”124 Every household had a person (primarily a woman or child) whose job it was to be physically present to procure food.125 Łódź ghetto survivor Alfred Dube writes of his four-year-old sister being forced to line up to purchase food at 5 a.m.126

Figure 3.3 Jews in the Warsaw ghetto awaiting their turn in the soup kitchen.

One’s ability to navigate the food lines was an important survival strategy because when food was limited, being at the end of the line could result in not receiving rations. For example, Kraków ghetto survivor Garfunkel said that when she and her father politely waited in line for soup, they might receive nothing but water or possibly a turnip in their soup.127 To ensure they received food, people shoved and beat one another for a better place in line.128 Sara Selver-Urbach described what happened when her mother, who was adept at jostling to keep her place in line, became ill: “We were in dire circumstances … (because) we did not know how to force our way, a very necessary skill in those days. Somehow we always found ourselves at the tail end of the queue, and when the supply was limited, we were among those who came away empty-handed.”129 People endured physical abuse in the food lines only to be rewarded with substandard food. As Zelkowicz wrote of the food lines, “All that counts is to pay the cashier, receive a coupon for the warehouse, and accept whatever the warehouseman lays in your hands as long as it is chewable, if not edible.” He also wrote of the joy of ghetto inhabitants lining up to receive two kilograms of potatoes although the produce was “spoiled and grade B.”130

Physical altercations in food lines during famine situations are not uncommon.131 Memories of the Irish famine include tales that “the people were so famished that their compassion and consideration had left them. Healthy men used their strength to muscle past women, children, and the weak. They trampled on top of one another, everybody trying to get close to the soup pot.”132 The violence on the ghetto food lines was such that it is included in the Encyclopedia of the Ghetto that was created by Łódź ghetto archivists. The word balagan means to make a mess, but in the ghetto, it came to refer specifically to the chaos connected to the ghetto’s food lines. The editors of the encyclopedia note:

The word “balegan” meant the front of such a line, compromised of a whole cluster of people crowding the entrance to the distribution point or at the counter window of the ration cards collection office. Typically, a “balegan” is created in the following way: several hours before the distribution point opens, people start gathering in front of it, hoping to pick up their rations as quickly as possible. One by one, they join the waiting line. They stand in it until so-called “tough guys” (vide “Mocni”) or “Usurpers” in turn, show up just before opening time. “Tough guys” push out those standing closest to the entrance or counter windows and take their places at the head of the line. “Usurpers” in turn, citing some “witnesses,” take over the best places, claiming that they had reserved them earlier. Those who have been pushed out of the line refuse to go to the end and gather around the front, thus starting to form a “balegan,” which later proceeds to storm the door of a “cooperative” or an office counter.133

The targets of many food riots were often the well-to-do who could afford the high prices or ghetto elites who skipped the line, causing resentment.134 One ghetto inhabitant was a witness to line skipping that caused a mini riot. He and his neighbor woke up at 5 a.m. and went to the bakery, where there was already a huge queue. At about 7 a.m. people started to get nervous and shouted that the baker should begin giving out bread, but he said that he had to wait for the commissioner. After a while, six people came, wearing blue hats – the same hats the Jewish police wore – and they did not stand in line but went straight to the baker, who gave them two loaves each. People expected bread distribution to begin then, but it did not. The crowd began throwing stones in the direction of the bakery. The Jewish police came and started to “clean up.” People got so angry that they started to fight.135 This anger over line skipping and favoritism led in June 1942 to an announcement in the Łódź ghetto that each person was required to wait their turn in the food distribution lines and that no one was to receive preferential treatment.136 However, there remained in the ghetto line-free special distribution centers for those in privileged situations. For the highest-level elites, food was delivered to their home.137

Conclusion

Communal coping mechanisms for providing food to the ghetto inhabitants varied across cities. In Warsaw and Kraków, a combination of rations and private provisioning was in use, while in Łódź, a ration system ultimately prevailed over private food sources. These food distribution mechanisms were influenced by the Jewish leadership, the local German administration, and the relative openness of the ghettos. The seizure of mail packages to benefit the least fortunate in the Łódź ghetto demonstrates the tensions between communal survival strategies and individual survival strategies. It also sharply contrasts with the Warsaw German administration’s seizure of packages to benefit the German population. In all three ghettos, the different mechanisms for food distribution favored different groups of individuals. In Łódź, Jewish ghetto administration officials and factory workers benefited from supplemental rations, while in Kraków and Warsaw, the private markets meant that economic position played a key role in food access. These differences reflect the structures of the ghetto as imposed by the Germans as well as prewar sensibilities of these communal leaderships.

All three ghettos employed communal coping mechanisms to supplement the scarce food resources through a variety of means. Food processing, particularly to minimize food waste, and agricultural projects were ways in which the community sought to expand food provisions. Soup kitchens and supplemental welfare payments were used to help supply food to the impoverished of the ghetto.