The Middle East generally (Bar-Yosef Reference Bar-Yosef1994) and Iran specifically (Vahdati Nasab et al. Reference Vahdati Nasab, Clark and Torkamandi2013) have become a focus for the study of human migration between South-west Asia and Central and Eastern Asia during the Pleistocene (Asgari Khaneghah et al. Reference Asgari Khaneghah, Berillon, Bahain, Zeitoun and Chevrier2005; Biglari & Shidrang Reference Biglari and Shidrang2006; Heydari Guran Reference Heydari Guran, Fahimi and Alizadeh2012). In Iran, studies of the Palaeolithic have concentrated on the Zagros and Alborz areas, but recent work in the sub-montane areas, desert margins and lowland plains have also revealed interesting results regarding the activities of hunter-gatherer societies (Biglari et al. Reference Biglari, Nokandeh and Heydari Guran2000; Dashtizadeh Reference Dashtizadeh2009; Vahdati Nasab et al. Reference Vahdati Nasab, Mollasalehi, Saeedpour and Jamshidi2009, Reference Vahdati Nasab, Roustaei, Rezvani, Matthiae, Pinnock, Nigro and Marchetti2010, Reference Vahdati Nasab, Clark and Torkamandi2013; Darabi et al. Reference Darabi, Javanmardzadeh, Beshkani and Jami-Alahmadi2012).

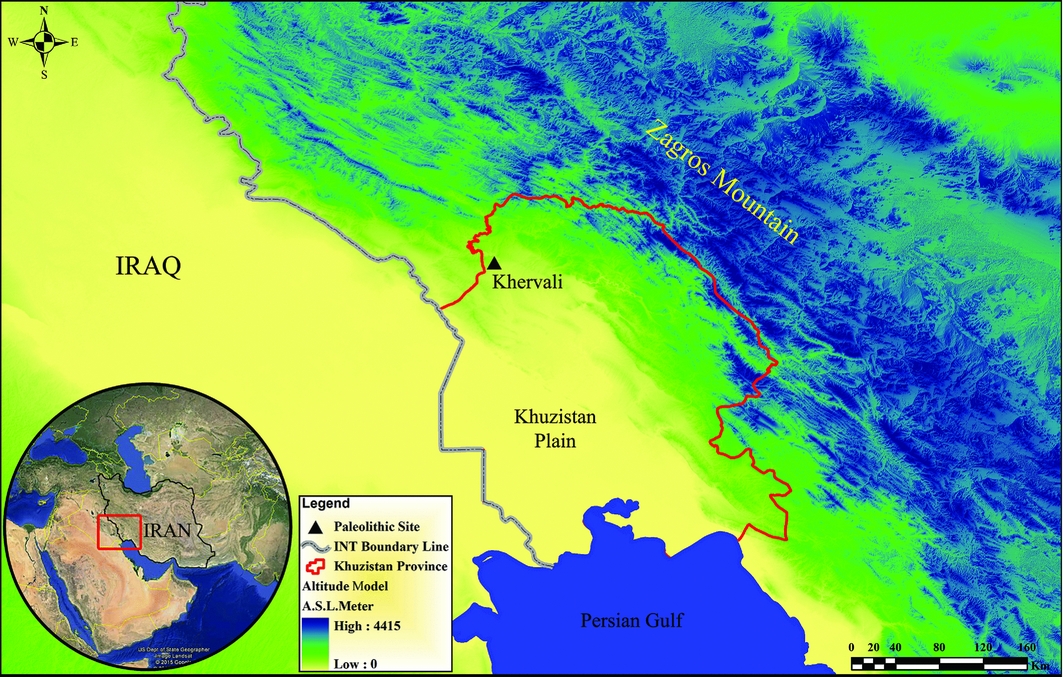

A survey was conducted in 2012, directed by Loqhman Ahmadzadeh Shouhani, along the western side of the Karkheh River in the north of the province of Khuzestan, south-west Iran. A total of 72 archaeological sites were identified. One of these—the site of Khervali located in the Khervali Valley, 950m to the west of the Karkheh Dam (Figures 1 & 2)—was dated to the Paleolithic and subject to further systematic investigation.

Figure 1. Geographic location map of Khervali Valley.

Figure 2. Location of Khervali Valley near Karkheh River (left bottom), and a view of the middle part of the Khervali Valley (conglomerate landscape).

Khervali, extending across an area of approximately 630 × 2320m2, is located at 130–160m asl in an open valley in the foothills to the north of Susa (the northern part of the Susiana Plain). The surface of the site is relatively flat, sloping slightly north-west to south-east. The raised elevation of the site compared to the surrounding plain has protected it from the Holocene sedimentation process experienced below. The site lies directly on the Bakhtyari Conglomerate Formation (Figure 3), and is littered with rounded pieces of sandstone and an abundance of chert. A seasonal river flows through the Khervali Valley joining the Karkheh River. Unfortunately, the site has suffered extensive damage as a result of the construction of an asphalt access road for the Karkheh Dam.

Figure 3. Geological map of Susa township; the yellow part is the Bakhtyari Formation (BK: conglomerate).

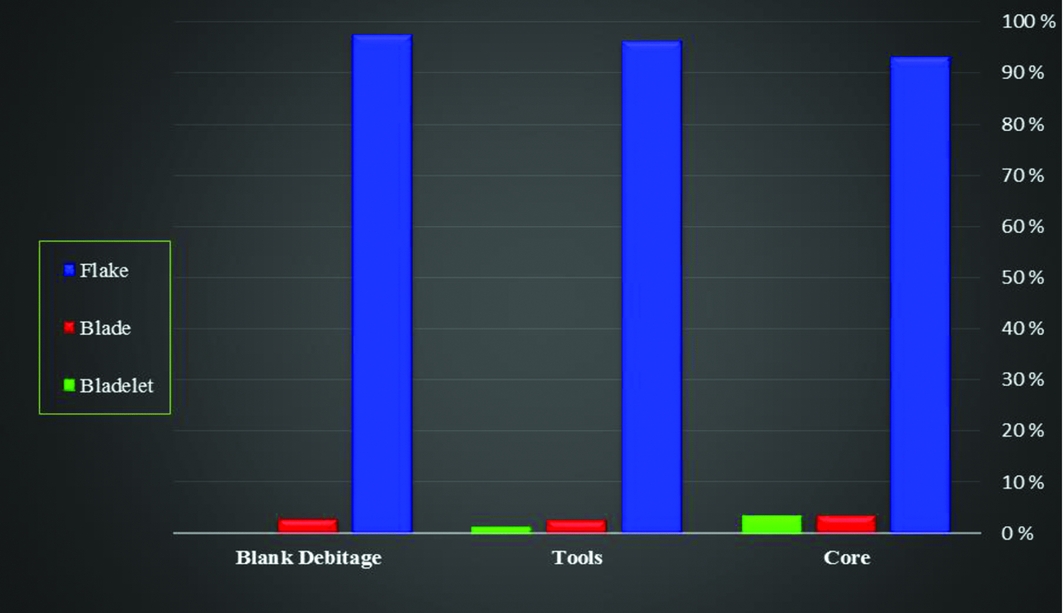

Systematic survey of the Khervali site, including four circular concentrations with diameters of 20m, recovered 330 stone tools such as cores, core fragments and blank debitage. The cores can be categorised into three main groups: flakes (93.4%), blades (3.3%) and bladelets (3.3%), which are reduced in an irregular and unidirectional way. Seventy-two tools, 23% of the total, include retouched pieces, notch-denticulate pieces, scrapers such as a dejete, a single-sided scraper, a heavy duty scraper and a transverse scraper (Figure 4 & 5). Of the tools, those made of flakes, a total of 73 pieces, are the most frequent (96%); two tools are made of blades (2.6%), and a single tool is made of a bladelet (1.3%). Among the 73 pieces of debitage, 97.3% were separated from the core by flaking, and 2.7% by blading techniques. Given the frequency of flaking (Figure 6), the variety of scrapers and notch-denticulate tools, and the use of the Levallois technique, a Middle Palaeolithic date for the site is probable.

Figure 4. Abundance of the Khervali tools.

Figure 5. Some of the collected artefacts from the Khervali site: 1) core/chopper; 2) flake core 3) heavy duty scraper; 4–5) levallois flake; 6–7) denticulate flake; 8) scraper with heavy retouch; 9) dejete; 10) single-sided scraper; 11) transverse scraper.

Figure 6. Chart of blank technology.

The tools used the raw materials available in the Khervali Valley, including flint, chert, jasper, opal, and occasionally sandstone and quartz. Most of the tools are made of light-brown or crimson flint, and, in some cases, even appear in green and red, grey or cream flint. This raw material is the principal characteristic of the Bakhtyari Conglomerate Formation (Darvishzadeh Reference Darvishzadeh1991) on which the site was clearly and carefully located.

The discovery of the site at Khervali provides a rare example of a Palaeolithic site located between the Zagros Mountains and the lowlands of the Khuzestan Plain. Further study of this site will contribute to an understanding of not only the occupation of these regions during the Palaeolithic, but also to the broader study of the migration of humans into Central and Eastern Asia during the Pleistocene.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hamed Vahdati Nasab, Department of Archaeology, Tarbiat Modares University, and Sajjad Alibaigi, Department of Archaeology, Razi University, for commenting on this article.