The purpose of this special issue of Advances in Archaeological Practice is for contributors to share their perspectives on and experiences with cultivating and nurturing collaborations between archaeologists and “responsible and responsive stewards” (RRS; Pitblado et al. Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018:16). This article is unique because I am the only single-author contributor to the issue writing from the nonarchaeologist perspective. I have no formal training in archaeology. My knowledge of the subject derives primarily from personal study and from interacting with and learning from friends who are professional archaeologists.

The objective of this article is to share my own journey from artifact collector to RRS, and more importantly, the lessons it has taught me about how professional archaeologists can most effectively cultivate relationships with collectors and others interested in archaeology.

Because I am not trained in the way many professional archaeologists have been, I may present ideas or opinions that might seem unethical from a professional perspective, even though they are technically legal. And that is the basic standard to which amateur archaeologists and collectors are held: legal collection of artifacts. Education is the best tool to move a group of people to a different standard of ethics. But professionals need to be willing to engage with amateur archaeologists and collector groups. Otherwise, how will people from these groups ever progress toward more informed ethics and thought? Even if amateur collectors wanted to spend their time reading journal articles, most of them have no access to professional journals. Personal interaction is the key.

Why should professional archaeologists interact with amateur archaeologists and artifact collectors? First, professional archaeologists have neither the time nor resources to identify, analyze, and report all the sites in their research or study areas. Clearly, most of the archaeological sites and artifacts found in the United States have not been found by archaeologists but by collectors and members of the general public (Shott Reference Shott2017). How many other significant sites have been discovered but are known to only a handful of locals? For example, Dallam and Hartley Counties in Texas have only 46 and 51 archaeological sites, respectively, currently recorded by the state of Texas (Texas Archeological Site Atlas 2021). Dallam County alone is larger than the state of Rhode Island, and it is just one of 26 counties in the Panhandle of Texas. In the three square miles of Dallam and Hartley Counties that I had access to, I was able to find numerous artifacts that I grouped into five distinct sites. I am confident that this small area has many more sites that a trained archaeologist could discover and document. It would take many lifetimes to identify and record all the sites in the Texas Panhandle.

A second reason that professional archaeologists should interact with amateur archaeologists is to preserve and document the rich history of private collections that have been assembled over decades. This information—including potential sites, rare artifacts, and access to an expanded network of collectors—could illuminate a great deal in archaeology (LaBelle Reference LaBelle, Zimmerman, Vitelli and Hollowell-Zimmer2003). Our knowledge of the Clovis culture, for example, would be much different if professional archaeologists had snubbed collectors who had brought late Pleistocene finds to their attention (Pitblado Reference Pitblado2014a).

Finally, it is the duty of archaeologists to “contribute to the preservation of non-federally owned prehistoric and historic resources and give maximum encouragement to organizations and individuals undertaking preservation by private means” (National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, Section 2.4) as well as to “enlist public support for the stewardship of the archaeological record” (Society for American Archaeology 1996, Ethics Principle 4). The most efficient and effective method of accomplishing this is to work with nonprofessionals (Pitblado Reference Pitblado2014b).

In this article, I begin by providing background about my own transition from being an interested artifact collector to being an RRS. I highlight the key role that a professional archaeologist who is well versed in collaborative best practices played in my evolution. I then share just a few examples of the finds I have made as an RRS and the data generated from them. My goal in that subsection is to illustrate the unique findings that can result from a strong archaeologist-RRS relationship. I then discuss my own motivations for collecting, in the hope of showing readers that there may be more common ground than many think between RRS and professional archaeologists (Kinnear Reference Kinnear2008). Finally, I present a list of what I have found to be best practices for archaeologists who want to cultivate and nurture collaborative relationships with RRS in their study areas.

MY STORY

I have always loved science and nature. However, it was not until my senior year of high school that I became a fan of anthropology and archaeology. I signed up for an anthropology class taught by a visiting college professor. She taught about religious rites, languages, and cannibalism. We discussed evolution and ancient cultures, and how such customs as rites of passage and marriage can vary across cultures. I was especially fascinated with the tribal cultures in South America, which remain quite traditional, even in an otherwise modern society.

The class opened my mind to perspectives and insights I had never thought about before. I do not remember everything we discussed, but I do remember thinking through these new ideas for many months after the class ended.

A few years into my career, I received a job offer in the Panhandle of Texas, managing a farm for a large organic dairy operation. One of the reasons I was excited about the job was the potential of finding an authentic Native American artifact, which are commonly found in this area. As I traveled around the farm, I would occasionally find lithic flakes, but it took almost six months before I glanced down from my four-wheeler and was shocked to see a perfectly made corner-notched arrowpoint made from a gray chert I later came to know as Alibates silicified dolomite (Shaeffer Reference Shaeffer1958). It was astonishing to see such a beautiful and perfect object lying in the middle of a well-used farm road. I knew the laws of Texas allowed artifact collecting on private property, so I took a picture of the point, recorded the GPS location, and carefully carried it home.

This was a moment of true discovery. Not only did I find a perfect arrowpoint, but something was also awakened within me while holding that worked piece of stone in my hands. How was this point lost? Was it shot at a buffalo, an antelope, or possibly an enemy? Who made this point? Who (or what) was the last to touch it?

Although the farm at which I worked did not have any sites, I was able to gain access to other farms in the area. Over the next few years, I found many artifacts from the diverse groups of Indigenous people who had lived in this area. As with the first point, I took pictures with the GPS location and cataloged them according to the area found and their approximate age. In my quest to learn more about the artifacts, I consulted with local residents who had been collecting for decades, tried to identify the points through online databases, and even purchased a few books.

Shortly thereafter, as I pondered how I could get more information about the points and other artifacts I had found, I came across a poster at a local gas station with details about the Perryton Stone Age Fair (Westfall Reference Westfall2011). I imagined that if any group of people could tell me more about my finds, this would be the one. I hoped that this fair would have university archaeologists and experienced collectors who could tell me everything about what I had found. I also noticed the statement “Buying, Selling, and Trading of Artifacts Is Not Permitted.” I did not need or want to sell anything, but it was curious to see that phrase on the poster (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Perryton Stone Age Fair poster (photograph by Scott Brosowske).

When I arrived at the Museum of the Plains in Perryton, Texas, early on that Saturday morning, the museum was already full of collectors with amazing assemblages of artifacts. I was in awe at the beautiful projectile points spanning human history on the American continent. This was much more than a “fishing expedition” hosted by archaeologists and government agencies to interrogate amateurs and collectors. This was an event that drew in hundreds of amateurs and collectors who could share information with each other with the added benefit of a few friendly and knowledgeable professional archaeologists available for tough questions, current theories, and guidance (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Perryton Stone Age Fair (photograph by James Coverdale).

After visiting all the displays, I pulled out my meager but proud collection and started asking people if they could give me any information about the points. Again and again, I was told to find Dr. Scott Brosowske, who could give me all the information I wanted. After some searching, I finally found him.

Scott, as he preferred to be called, seemed down to earth and genuinely interested in my points. He told me that the small quartzite Paleoindian artifact I had found was actually a Folsom base and that my nearly perfect lanceolate Clovis-shaped point was a Jimmy Allen point from the late Paleoindian period. I was not happy with his identification. I wanted it to be a Plainview point because they are much older and native to the Texas plains. I wrote down his contact information and returned home with much more knowledge and available resources.

As I thought about Scott's opinion over the next few days, I was still not convinced that he was correct about his identification of the Allen point. I truly believed it to be a Plainview point, so I wrote Scott an e-mail asking a few questions and pushing back a bit on his conclusion. I asked him why a late Paleoindian point such as an Allen point would be the exact same shape as the much earlier Plainview and Clovis points. Why would the Paleoindian cultures depart from the general Clovis/Plainview shape for thousands of years (Hell Gap, Eden, Scottsbluff, etc.) only to come back to the same shape at the very end of the Paleoindian period? I was also curious as to why these Paleoindian points were so much better made than the later points of the Archaic and Ceramic period cultures.

He replied to my e-mail with a good explanation along with some articles. His basic point was that if the point had parallel oblique flaking, it was definitely late Paleoindian. I wanted to learn more, so I asked if I could visit him the next time I was in the area. He sent me directions to his lab, along with an invitation to come over when I had some time.

Not long after this, I found myself in his office looking at some of his points, discussing various questions, and showing him some of the other points I had collected. In addition to introducing me to his wife, Lisa, and fellow employee, James, he gave me Ancient Man in North America (Wormington Reference Wormington1949) and a few more articles. I devoured both the book—reading it through several times—and the articles. This visit initiated a great friendship and mentoring experience.

I continued visiting Scott regularly as our schedules would allow. Sometimes I would bring points I had found, and he would tell me about the time period during which they were made, the source material, and other background information. Other times I visited his lab and saw some of the collections that he had access to. On a few occasions, we went out into the field together to see sites that he had found around the area. I enjoyed seeing other sites in the Texas Panhandle with slightly different landscapes and topography than the kinds I was working on. He also introduced me to some of his friends and fellow archaeologists. I almost never left his lab without a few articles to read and a book recommendation.

Mentors pass on knowledge that is priceless. Scott scanned approximately 50 articles for me and gave me recommendations for over a dozen books, all of which I purchased and read repeatedly. He spent many hours discussing theories and the background associated with the artifacts I had found. I also enjoyed hearing what motivated him to study archaeology and how his experience of finding a complete Folsom projectile point in a developing subdivision over 30 years ago had generated an interest in archaeology that changed his career path.

A good relationship is beneficial to both parties. One may ask what Scott got out of this arrangement. When the question was put to Scott, his response was, “Why should I necessarily have to get something out of it? I mean, I am just doing my job of public outreach and education and getting paid for doing it. It is like a teacher or a professor. They get paid to teach. What else do people expect them to get out of it? Satisfaction of seeing students learn and grow? I do it because I enjoy it, and it is what my mentors did and still do for me” (Scott Brosowske, personal communication 2021).

Although I cannot begin to repay Scott for the impact he has had on my life, I have tried to reciprocate by sharing information about sites and artifacts with him and taking him out into the field where I found some of my Paleoindian points. I set up a meeting at the XIT Museum in Dalhart, Texas, which enabled Scott to look at their collection of artifacts. I have also given his name to many of my friends to increase his network of avocational archaeologists and landowners. Because I have a background in agriculture, I have also given him agronomic advice for his heritage garden. I will never forget his kindness, patience, and contagious enthusiasm for archaeology.

SAMPLE FINDINGS

After years of collecting and documenting artifacts and site locations in personal journals and GPS-embedded pictures, I felt an obligation to summarize the artifacts I had found—along with pictures and site descriptions—and share them for future reference. The articles Scott had shared with me had shown me the value of documenting finds, and Scott had also mentioned the importance of doing so.

Archaeological data from Dallam and Hartley Counties in Texas are scarce in the state files (Texas Archeological Site Atlas 2021). For instance, Dallam has only 46 recorded archaeological sites, and Hartley has 51 sites. In contrast, there are 275 archaeological sites in neighboring Union County, New Mexico, and 81 recorded sites to the south in Oldham County, Texas (LaBelle Reference LaBelle2005:95; Texas Archeological Sites Atlas 2021). I was excited to add my information to that of so many great people who have gone before me.

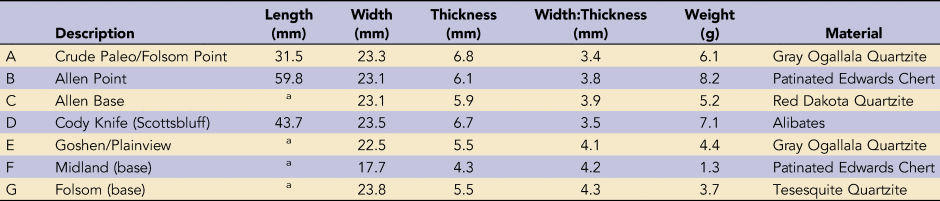

My initial draft was simple and covered the basics of what artifacts I had found and where I had found them, along with some pictures and tables containing measurements such as those found below (Figures 3 and 4; Table 1).

Figure 3. Looking south to Site #3: LARS North Site on east slope of hilltop (photograph by author).

Figure 4. Author's parents enjoying time collecting with their son (photograph by author).

Table 1. Paleoindian Point Measurements.

a Incomplete measurement.

Not only was it exciting to document my finds, but it also raised new questions, such as why the widths of the Paleoindian points are so consistent.

I also included other artifacts I had found—which may or may not be important—such as small, smooth, white quartzite stones. In this area, lithic material does not occur, so Native peoples had obviously transported them to these sites. These stones stuck out from the other lithic fragments because they were pretty—something my own children would collect. Although I did not know if they were significant, I did not want to risk neglecting potentially valuable information.

I submitted my report to Scott, and he encouraged me to develop my report into an article for publication. I had some time and liked the idea, so I agreed. He sent me an outline of a typical report, which included an introduction, details about the study area, the cultural background, site descriptions, and other types of information. I also extracted information from the books I had read and the articles Scott had sent me. The current version of this report remains unpublished, but we are working together to find a suitable publisher for it. With the documentation completed, I can rest easier knowing I have done my part, and I look forward to sharing the eventual published version with a much broader audience.

MOTIVATIONS

The reasons people are interested in collecting artifacts vary greatly. For simplicity and for the sake of this discussion, I will refer to anyone who is not a professional archaeologist as an amateur or collector.

I think some amateurs are motivated by the “thrill of the hunt.” There is something exciting about expending great effort to pursue something. How much money would one have to pay an employee to wake up at 3:00 a.m., drive for a few hours, walk a few miles in difficult and remote terrain, and then sit in subzero temperatures for hours? Yet, many hunters and fishermen pay large amounts of money to do just this. What is this instinct that lies within us?

Another motivation is the chance to get out in nature and enjoy the beauty of the world. Some find peace in being alone with their own thoughts and experiences. Others love to be outside with family and friends and enjoy strengthening relationships through outdoor activities.

Still others are motivated by the thought of finding a rare or unusual artifact. There is always that chance that one will expend a small amount of time and find something amazing, such as a perfect Clovis point.

An additional motivation can be the connection one feels with different people from different cultures. This is harder to define, but it is quite real to me. One feels a connection to people long ago when holding a piece of stone that has been crafted by another human thousands of years before.

Although I cannot speak for all possible motivations, I can attempt to put my own motivations into words. I love being outside. I grew up hiking in the mountains and enjoy fly-fishing, hunting, hiking, camping, and rock climbing. I love being alone with my thoughts. I can learn a lot when the pace of life slows down in the quiet of the wilderness. I also enjoy searching for artifacts with my children and my parents. Some of the greatest memories I have are looking for rocks with my father or watching my daughter pick up a perfect arrowpoint. I also love the thrill of the hunt and the idea of possibly finding something rich in historic value.

The greatest motivation for me is the idea that another human being, from a culture totally foreign to my own, has touched and worked the piece of stone in my hands. When I am holding a well-made projectile point, I often wonder, Who was the artist of this beautiful piece of craftmanship? What were the person's worries on the day of making this point? Did they have small children they were trying to feed? What was their family group like? Were they concerned about enemies, disease, or starvation? How (and what) did they worship? When I see a mano or a scraper, I cannot help but think about the hard work that person had to do. Were they forced to work by others, or were they free to do as they wished? Did they enjoy the same sunset, the same wind, and the same plants that I am enjoying right now? I love to imagine the people of the Paleoindian culture and who they must have been to produce such exquisite and precise workmanship. What was lost when the Paleoindian cultures were replaced by later cultures?

Although I have identified some of the many factors that inspire amateurs, I imagine that these same motivations are shared by many professional archaeologists as well. How many professional archaeologists love to get out in the quiet stillness of nature? How many are absolutely thrilled at finding a rare artifact? How many are obsessed with their collections? Most important, I have not met anyone in either group who does not enjoy hearing the history and theories behind artifacts and the land where they were found. That is, after all, what archaeology is all about.

WORKING TOGETHER AS STEWARDS OF ARCHAEOLOGY

As professional archaeologists, you have so much to offer. I hope my experience has emphasized a few examples of how you can continue to both influence people and preserve the artifacts, along with the stories of their discovery. The following are some suggestions:

• As stated previously, many archaeological sites were/are found by amateurs. How are you utilizing these passionate groups to further your own research? How many of the sites you have worked on have been found by locals? If the number is low, you may be doing local collectors and the entire field of archaeology a disservice. Artifacts will continue to be found with or without your involvement. Why not influence the process through targeted outreach? The farther you venture out of your academic circles, the more influence you will have.

• Once you have contact information from amateurs and collectors, keep in touch with them. Send articles, personal notes, and invitations to archaeological events and fairs. After you establish a relationship with them, perhaps invite them to participate in an appropriate field, lab, or research project.

• Ensure that your contact information is easy to find. Ask neighbors and friends to try to find you and your outreach groups on the internet without using your name. You may be more difficult to find than you realize.

• Push your students and those you mentor to think in new ways. Challenge their beliefs, and help them see the beauty of diverse cultures and artifacts. Your influence will be much greater if you treat them with respect, not condescension.

• Teach the value of documentation. The first question after congratulating an excited amateur on a great find should be “Did you (or how are you going to) document this find?” If the amateur has neither the time nor the inclination to do this, ask a student to work with them to ensure that everything is well documented.

• Teach the ethics of not selling artifacts. Remember that one of the first thoughts many rockhounds and collectors have when they find an artifact is, “How much money is this worth?” I can imagine that the idea of artifacts themselves not having a monetary value has been so ingrained in your training that you do not even think about it anymore. However, it is still legal to sell artifacts. How will you convince someone that has just found a Clovis point that it should not be sold? Little hints such as “Buying, Selling or Trading of Artifacts Is Not Permitted” on the poster for the Perryton Stone Age Fair and respectful interactions with professional archaeologists helped me understand that selling artifacts was not ethical. Where else would I have learned that?

• Treating a collector with contempt or communicating in a condescending manner will burn a bridge not only with that individual but with that individual's family and friends as well. On the other hand, a good interaction can open doors with hundreds of people and potentially yield a great deal of valuable information about the sites in a given area.

• Enthusiasm is contagious. Remembering your passion for archaeology will help you connect to amateurs and other collectors. I was drawn to a few archaeologists at the first Stone Age Fair I attended because I could feel both their passion and their humble demeanor.

• In many other sciences, there has been a strong move to democratize power and knowledge. For example, in the fields of education, public health, and sociology, there are movements toward participatory action research, or even more participatory methods that seek to empower communities instead of treating them as children. To move archaeology to the next level, professionals must seek even more participatory methods with amateurs and local communities. This certainly includes Indigenous groups but many others as well. In the medical field, they now call it “knowledge translation.” This is the idea that professionals (doctors) have one form of knowledge but that patients also have knowledge about themselves. The purpose should be to bring those two forms of knowledge together and translate them to promote mutual respect, empowerment, and trust (Sudsawad Reference Sudsawad2007).

There are many possible ways that professional archaeologists and collectors could collaborate to not only develop their own relationships but increase interest in archaeology among the general public (Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Kuhnel, Magnani, Hittner, Chodoronek and Porter2017). There are many significant and intriguing artifacts to be found in the local collections of amateur archaeologists that would be of great interest to professionals as well as the general public. Likewise, there are many amazing artifacts stored in the dark caverns of academic institutions and museums that remain hidden and forgotten. Everyone wins when these significant artifacts are rediscovered and brought to light for the benefit of people from all walks of life.

CONCLUSION

I occasionally ask my children which they think I love more: my arrowhead collection or them. Every time, the kids laughingly tell me that it is my arrowheads. I really do love my children more than these artifacts. And I love the memories I have of finding artifacts with them by my side most of all. That is my motivation. I hope you never forget yours.

My experience has been filled with passionate mentors and knowledgeable teachers who imparted their expertise both in personal interactions as well as in books and articles. As with many successful ventures, fortune looked favorably on me when I found a poster for the Perryton Stone Age Fair in a gas station near my office. There are countless other potentially responsible and responsive stewards hoping to learn about what they have found and to share information for the sake of furthering archaeology. Our job is now to find them and work together to bring the beauty and wonder of archaeological discovery to future generations.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank, first and foremost, Scott Brosowske for his friendship and willingness to share his expertise. Without Scott's unique combination of knowledge and encouragement, this article would never have been written, and everything found would be hidden away in some container, unknown and forgotten. Many books and articles were purchased, downloaded, and copied at Scott's direction. His encouragement was priceless. I would also like to thank the Harold and Kirk Courson Families for funding and supporting Courson Archaeological Research and the Perryton Stone Age Fair.

The feedback from the anonymous reviewers was also instrumental in my understanding more about the culture of professional archaeologists and how to tailor this article to that audience. I would also like to thank Lorelyn Wright, Sam Wright, and Joseph Wright for their valuable insights, editing, and feedback.

Finally, my thanks go to Scott Brosowske, Bonnie Pitblado, and Jason LaBelle for their efforts to bridge the gap between professional archaeologists and amateur collectors. These pioneers have neither any idea how many people they reach nor what walls they tear down by responding to amateur collectors in kindness and encouragement and illuminating the wonders of archaeology. Too much of the beauty of archaeology is never allowed to see the light of day or receive the appreciation of the general public due to fear, pride, and judgment on the part of both professional archaeologists and collectors. These mentor-scientists, and many others in their field, have recognized that when a relationship is established with an amateur collector, it not only expands the understanding of archaeology in an area but also creates a learning environment that nurtures eager minds and fosters true appreciation of archaeology.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the author.