Orthodox Roman Christians (Nicene orthodox in the West and Chalcedonian orthodox in the East) established themselves in the late Roman world, a time of great social and political transition, and flourished in the Migration Period of the fifth and sixth centuries. It is widely accepted that Nicene Christians in the West saw themselves as partakers in the Roman world, dissociating themselves from the allegedly non-Roman migrating peoples who still adhered to paganism or non-orthodox Christian faiths, in particular Arianism. Arian migrants, on the other hand, claiming orthodoxy for themselves, certainly did not always agree with being stigmatized as non-Roman.Footnote 1 For historians, however, the lifespan of the compound ‘Roman’ and ‘orthodox’ is a limited one. At the threshold of the early Middle Ages, ‘Barbarian beliefs’ were eroded by the increasing acculturation of migrants. Their progressive inclusion into the Nicene church changed the character of the church into a global one, no longer bound to Roman identity.Footnote 2

In what sense did Christians in the post-Roman world consider themselves to be Roman exactly? Was their Romanness, as much scholarship on post-Roman Christianity often assumes, a function of their Christianness? Was Romanness a bundle of independent meanings which Christians subscribed to? This book interrogates material sources to better understand what implications the association of Christianity and Romanness had for the religious identity of Christians in the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries. It presents evidence of Christian communities who integrated traditional Graeco-Roman cultural practices into their vision of Christianity and at times broadened the concept of Christianness beyond orthodoxy. The art and material culture of the period show us that Christians treated Graeco-Roman cultural practices, some of which were considered un-Christian by high-ranking church representatives, as part of Christian culture.Footnote 3 Their identity as Romans (or aspirations to this identity) influenced Christians’ understandings of what counted as proper and orthodox ways of performing Christianity.

Hence, we should reconsider the conventional belief that late antique Romans were primarily Christians. The evidence presented in this book suggests an alternative perspective: that Christian identity could be a product of Roman identity. By embracing Christianity, neophytes also joined the community of the inheritors of the Graeco-Roman cultural koine. While determining whether individuals were more motivated by one or the other incentive for baptism may often be challenging, if not impossible, the analysis of visual and material culture brings this question to the forefront.

In response to the dominant approach of dealing with questions of continuity and rupture with the classical past in late antique Christianity by analysing texts, I will shift the focus to what an analysis of material and visual culture can contribute to the study of Christian religiosity. Here I follow an approach to religion that privileges lived practice over doctrinal ambitions. While the ‘lived religion’ approach has been productive, especially in the field of Roman religion, the study of late antique Christian art has not yet taken sufficient advantage of this and other approaches which take the exploration of non-elitist, local, and individual perspectives as seriously as the incommensurably better-studied testimonies of the church fathers.Footnote 4

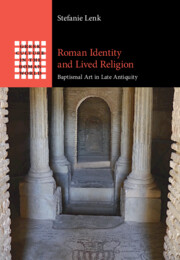

I focus my argument on the decoration of Mediterranean baptisteries, which were built, maintained, and refurbished between the fifth and seventh centuries – spaces which were instrumental to the formation of Christian religious identity in late antiquity. Under the guidance of their ecclesiastical leaders, Christian communities created spaces and celebrated baptismal ceremonies in them, crafting a vision of Christianity in which Graeco-Roman visual culture was an intrinsic component. Often, the material evidence does not allow us to distinguish between baptisteries used by local Roman or Romanized populations and those used by migrants. Where it does, however, it is clear that Graeco-Roman cultural practices were welcomed in the religious lives of both.

All the case studies are situated in the western half of the Mediterranean. One might question why the book focuses on the Roman West, especially when the artistic examples mentioned relate to a visual culture prevalent in Graeco-Roman antiquity throughout the Mediterranean and beyond. Shifting the focus to lesser-known examples of baptismal art in North Africa and on the Iberian Peninsula aims to challenge the popular view of the Byzantines – the Rhōmaîoi – as the self-proclaimed guardians of ancient Roman heritage, which sets the idea of a politically stable Byzantium apart from the so-called post-Roman West.Footnote 5 Without denying Byzantium’s strong identification with the Roman past, the persistence of Roman identity clearly extends across and indeed beyond the entire Mediterranean region. despite the progressive political disintegration of the western Roman Empire. Also the art, architecture, and liturgy of baptisteries in the West exhibit similar tendencies in the use and reuse of elements of Graeco-Roman culture as do those of the Byzantine East.

One of the striking results of the self-construction of the Roman Empire as a Graeco-Roman entity was that elements of Graeco-Roman culture serve as evidence in identifying signs of Roman identity.Footnote 6 I delve into questions of the interrelation of Roman identity and material culture in more detail below. For the moment, suffice it to say that, in a broad sense, I believe Glen Bowersock hit the nail on the head when contemplating the nature of what he called ‘Hellenism’ in late antiquity. In Byzantium and beyond, notably across the Byzantine lands of north Africa, southern Spain, and Italy, reconquered for Constantinople under the emperor Justinian in the mid sixth century, local communities expressed their unique traditions through language, myth, and imagery rooted in Greek culture. As demonstrated by Bowersock, these cultural amalgams were distinctly local yet allowed communication with other parts of the Helleno-Roman world.Footnote 7

Similarly, we should be cautious in attributing both local and universal characteristics to Graeco-Roman visual culture. It is possible that the same visual motif adorning a baptistery in Byzantium and another one in the post-Roman West could be interpreted similarly, with the only distinction being its cultural affiliation identified as ‘Hellenic’ in one place and as ‘Roman’ in the other. This does not negate the motif’s complex genesis over centuries of artmaking in the entangled Mediterranean. The subjectivity with which people, rooted in different localities, made sense of visual culture simply needs acknowledgement. Given that this book predominantly explores evidence from the West, I will refer from now on to Roman (visual and material) culture unless specifically addressing Greek traditions.

The case studies in this book form only a small part of the entirety of preserved late antique baptismal art in the western Mediterranean. Late antique baptismal art is particularly rich in modern Tunisia and Italy and can also be found in Algeria, on the Iberian Peninsula, and in southern France. The research for this book brought to light a total of sixty-three western Mediterranean baptismal decorations either still in situ or attested in texts containing information about the location and iconography of the imagery. I discuss six of these in depth (Figure 0.6): the baptisteries of Cuicul (modern-day Djémila in Algeria), Milreu, and Myrtilis Iulia (modern-day Mértola) in southern Portugal; the baptistery of Henchir el Koucha in Tunisia; and the Orthodox and Arian baptisteries of Ravenna.

Figure 0.6 Sites discussed in this book (printed in regular script).

The sixty-three examples can be divided into three categories: (a) eight examples depict Christian narrative scenes from the New Testament or holy figures; (b) thirty-two examples show ornamental, floral, or animal decorations which allude to the psalms or are combined with Christian symbols or inscriptions; and (c) twenty-three examples show ornamental, floral, or animal scenes which cannot be univocally identified with Christianity. Group (c) comprises most of the case studies, while the baptisteries of Ravenna belong to group (a). Numerically, the subset of the six cases discussed in this book is almost equal to group (a), the entirety of preserved baptismal narrative scenes in the western Mediterranean. Furthermore, I tackle only a fraction of the baptismal mosaics rooted in Roman visual culture, many of which form part of group (c).Footnote 8

The study of late antique baptismal art has produced a rich literature. The groundwork in the field was laid between the late nineteenth and the mid twentieth centuries, when attempts were made to establish an overview of early baptismal art as a unitary totality and define general iconographic trends.Footnote 9 The majority of research in the second half of the twentieth century has consisted of national inventories and typologies of baptismal architecture and art.Footnote 10 More recently, a number of studies concerned with local specificities have added nuance to earlier generalist accounts.Footnote 11 Interest in baptismal ritual and liturgy and their origins has also increased significantly in recent years.Footnote 12 Iconographical studies have emphasized the interconnections between baptismal liturgy and art and have placed a new emphasis on baptizands’ bodily experience of decorated baptismal spaces.Footnote 13

The most recent general accounts of baptismal art are Robin M. Jensen’s monographs Living Water: Images, Symbols, and Settings of Early Christian Baptism (2011) and Baptismal Imagery in Early Christianity: Ritual, Visual, and Theological Dimensions (2012).Footnote 14 Jensen is concerned with bringing the study of baptismal art together with the study of figurative baptismal language in scripture, liturgy, and the writings of the church fathers. Jensen’s thoroughly researched work, which provides a model for the study of baptismal art, concentrates on material evidence from the late antique Roman West, like the present study. Preserved instances of narrative imagery are rare in the Roman West and can usually only be found in the most elaborate baptismal settings. Many spaces are composed of images of birds, fish, other animals, shells, flowers, trees, vases, and water. Geometric patterns are often used in tandem with figurative imagery and sometimes dominate the baptismal space. Jensen sees sacramental or paradisiacal meanings expressed in most of the baptismal decorations which are free from narrative – a conclusion shared by a large part of the previously mentioned scholarship.Footnote 15

While I am far from contesting this view, it strikes me that the scholarship reaching this conclusion has often taken the massive body of empirical data from different contexts in the East and the West as evidence of an ideal, theologically conceptualized totality. The quantitative evidence of preserved baptismal decorations hardly backs scholars’ claims about the generally orthodox character of baptismal imagery. On the contrary, the numbers suggest that Christian adoptions of Graeco-Roman visual culture, which is bare of one-dimensional Christian significance, shaped late antique baptismal art considerably. As foundational and important as the search for baptismal iconography’s scriptural models from the Bible or the church fathers is, it also risks drawing a picture of a hermetic Christianity bent exclusively on orthodoxy. The universalist core assumption all too rarely grants baptismal imagery the potential to be experimental and discursive within a fissile, complex, and diverse range of Christianities.

The case studies presented in this book have been selected to nuance the common assumption that fifth- and sixth-century baptismal art generally endorses and promotes what scholarship would identify as orthodox Christian practice and belief. The results of the present study do not apply to the entirety of late antique baptismal art and do not constitute an alternative reading of baptismal art altogether. Yet, they counterbalance the prevalent vision of what the rite of baptism and decorations of baptisteries were meant to achieve. They also give substance to the growing conviction that late antique Christian identities were multi-faceted, bound to local Roman tradition, and could deviate from official Christian doctrine.

Rethinking Christian Identity: Multiple Identities

In recent decades, the traditional binary opposition of pagan and Christian has been extensively questioned.Footnote 16 Historians and archaeologists have stressed that, throughout history, Christians experienced their religion in less clear-cut ways than the writings of Christian apologists suggest.Footnote 17 Instead, many scholars assume that there was a certain flexibility in Christians’ self-conceptions, in regard to both the sheer multitude of confessions, factions, and heresies (Nicene, Arian, Donatist, Syrian, Egyptian, Pelagian, Nestorian, Manichaean, and others), and the readiness or unwillingness to adhere to Christianity’s claim to exclusivity.Footnote 18 Scholarship which focuses in detail on how Christians reconciled ongoing pagan traditions and the exclusivity of the Christian religion is, however, still a minority concern.Footnote 19 The popular view that in the fourth and fifth centuries Roman society developed a secular realm which was independent of the religious realm – an argument prominently advocated by Robert Markus – has slowly begun to be criticized.Footnote 20 Critics of this theory stress that, at this time, Christians were more integrated into environments still marked by Roman customs and institutions than Markus allowed for.Footnote 21 They also seek to deconstruct late antique notions of non-negotiable divides between pagans and Christians as discursive constructs used to establish a common identity among Christians.Footnote 22

In his contribution on Christian identities in North Africa from the third to the fifth centuries, historian Éric Rebillard, using sociological theories of identity formation, has challenged the view that the behaviour of North African Christians was predominantly determined by their Christianity.Footnote 23 Instead, he champions an approach which acknowledges the internal plurality of individuals and allows for the multiple social roles (‘multiple identities’ in Rebillard’s terminology) that a person ‘activates’ at any given time.Footnote 24 Rebillard considers being a Christian only one of many social roles a person could play in their lifetime. Rebillard’s approach is individualistic insofar as it questions the legitimacy of using ‘internally homogeneous and externally bounded groups’ – which is how many late antique Christian writers often used the term ‘Christians’ – as categories of study.Footnote 25

Rebillard argues that North African Christians had plural identities based on ‘category memberships [social identities] such as ethnicity, religion and occupation’.Footnote 26 Further, following sociologist Don Handelman, he holds that these category memberships were arranged laterally, meaning that a particular social identity will prevail in one situation, while a different identity will prevail in another. This lateral arrangement is opposed to hierarchical category memberships in which a certain category (religion, for instance) predominates and determines an individual’s behaviour over other categories.Footnote 27 A sermon of Augustine of Hippo (354–430) can be used as an illustration: ‘There are plenty of bad Christians who pore over astrological almanacs, inquiring into and observing auspicious seasons and days.’Footnote 28 Augustine is speaking about people who actively combine different identities. In a lateral category membership, this behaviour can seem perfectly plausible, while in a hierarchical category membership (like the one Augustine advocates), this kind of astrological interest is illicit and must be stigmatized (‘bad Christians’).Footnote 29

Rebillard’s plea for lateral category membership in late antique Christian identities thus introduces a model for thinking about religious affiliation, which allows for more refined interpretations of religious identifications than the schematic categorizations ‘Christian’, ‘pagan’, ‘semi-Christian’, and so on. Rebillard draws our attention to the possibility that Christian identity was accompanied by other identities which could (but did not have to) take centre stage.

What would lateral category memberships have meant in practice for Christians of the fifth to seventh centuries? Scholars of identity formation agree that actors commonly adopt more than a single role in social situations.Footnote 30 For a late antique Christian, this could, for instance, mean that she identified as a Christian community member, daughter, wife, patron of the arts, and so forth, and that in many situations more than one role was activated. She would have had to negotiate these roles, as they mutually determined her actions. A caveat is in order here. Rebillard, questioning the status of Christianness as the most prevalent identity category, is primarily concerned with lay Christianity in North Africa at the turn of the fifth century. In the context of this study, however, the actors examined – namely Christian communities building and using baptisteries – comprise both clerics and lay members who were spread across different locations and moments in the fifth to seventh centuries. Over the course of roughly three centuries, lay and ordained Christians differed in the degree to which their Christianness determined other aspects of their identities. In very general terms, we can expect that the advance of Christianization in these centuries also increased the salience of Christianness for the construction of personal identities.

This book is not concerned with identifying situations in which the identity category of Christianness was not ‘activated’ or was subordinate to others. On the contrary, we may assume that Christians would have been particularly aware of their Christian identity when visiting baptismal spaces. Nevertheless, the theory of multiple identities is still relevant to my argument, as operating with multiple identity categories can prevent the trivialization of Christians’ relationships with other aspects of their lives. For instance, iconographies and monuments like the ones discussed in this book have traditionally been seen as exemplary of the ‘Christianization’ of Roman society. While such observations are not untrue, they do not take into account that Christian works of art may have been intended to strengthen more than one identity. Stating that a work of art reflects the Christianization of a region without any further specification suggests that the work of art was principally understood in Christian terms. Any other ways in which it might have mattered fall off the radar. Effectively, what the work of art might reveal about the identity of its makers and recipients is decided before any serious consideration is given to the question of what its purpose was. In the language of identity theory, we could say that scholarship takes for granted a hierarchical category membership in which Christians did not care for certain objects beyond their Christian value.

Identity theory proposes that individuals seek to establish congruence between different, more or less salient identities.Footnote 31 How challenging this task is depends on how mutually exclusive these identities are. The more common ‘meanings’ that different identities share, the more sustainably they can be activated at the same time. Where identities share many ‘meanings’, verifying one identity will help verify the other. If, for instance, an individual maintains the role of an engineer, and the same individual maintains the role of a dedicated citizen, then planning his city’s new bridge will help him verify both identities. If, however, two identities have oppositional meanings, they cannot be verified at the same time. The person will likely re-identify in order to re-establish the congruence of their multiple identities.Footnote 32

As we saw in the beginning when we pondered the link between ‘Roman’ and ‘orthodox’, we have no difficulty in acknowledging that Christian identity and Roman identity were considered congruent enough to be acted out together, that is, that they shared enough ‘meanings’ to verify one another. We accept that those who lived with Roman traditions were Christians as a matter of course. Likewise, we agree that Christian spaces projected a vision of Christianity which was, for instance, inclusive of Roman visual and material culture.

On top of this, what this book proposes is that the constant negotiation of the lateral category memberships Romanness and Christianness affected the religious identity of Christians. Acting out several identities together, this book argues, had an impact on how each of them was defined and nuanced. In other words, what being a Christian meant to Christians depended on how they enacted their Roman identity. We will explore different nuances of this interplay across the late antique western Mediterranean.

As a starting point, we will encounter a Christian community in today’s Algeria which, material culture suggests, emphasized its belonging to traditional Roman culture over that of its Christianness (Chapter 1). Further case studies indicate that some Christian communities in the late antique Roman West visualized their religiosity in terms that Christian authorities considered unorthodox (Chapter 2). These visualizations, however, might well have been in line with individual understandings of orthodoxy. Finally, I suggest by means of visual analysis that Christian communities in Ravenna deliberately established an ancestral relationship between Christianity and the Graeco-Roman world. Simultaneously, they associated the latter with antiquity, a connection that needed to be surpassed (Chapter 3).

The practice of simultaneously identifying with both Christianity and Romanness in baptismal spaces in particular had potentially long-term consequences for entire communities’ understandings of Christianity. As will be argued in the next section, baptism was experienced as constitutive of the construction of Christian identity and could affect future generations’ ideas of what it meant to be Christian.

The Baptistery as a Place of Christian Identity Construction

In this book, I propose the study of decorations of baptismal spaces as a means to examine Christian identity construction. Made for all who wished to be baptized, baptismal art and architecture are, according to the missionary logic of conversion, meant for everyone.Footnote 33 They are, as it were, situated dogmatically at the very heart of the church. That the sacrament initiating the profession of Christian truth could have taken place in sight of imagery with the potential to undermine Christian doctrine would thus require further explanation. Indeed, pre-Christian imagery is occasionally found in a variety of Christian communal spaces in late antiquity, and all these occurrences deserve attention. The baptismal space, however, has a special status which requires particularly careful examination. This special status derives from where the baptismal rite is situated semiotically in the life of a Christian.

Baptism affects the spiritual rebirth of the baptizand as a member of the body of Christ and is the precondition for eternal life in heaven.Footnote 34 Thus, only the baptized could receive Christian burial.Footnote 35 In life too, the sacrament was a momentous turning point. All but the baptized were excluded from Eucharistic prayers and communion.Footnote 36 With baptism came the understanding of the true nature of Christ. The Christian mysteries, the nature of the Trinity, and the meaning of the Eucharist were revealed in the process of preparation for, or retrospective explanation of, the baptismal rite.Footnote 37 At the same time, the official profession of Christian faith was another unprecedented requirement in the life of a Christian.

Textual evidence suggests that the late antique baptismal ceremony was preceded by a period of catechesis, in addition to many other ceremonies of spiritual cleansing, exhortation, and inner contemplation. The creed was learned by heart as part of the catechetical lessons. Augustine, who is the prime source for baptismal liturgy in the Latin-speaking world of the fifth century, made catechumens profess the creed individually the day or night before their baptism.Footnote 38 The introduction of the credal recitation, it has been argued, had implications for the faith of the catechumens. Through it, their faith was meant to change from a personal commitment to Christ into a belief in the body of doctrines necessary for the baptismal ceremony.Footnote 39 During the ceremony itself, at least where the Nicene rite was followed, the baptized were immersed three times in the name of the Trinity, progressing from the name of the Father and the Son to the Holy Spirit. This had to be affirmed each time by the baptized.Footnote 40 Augustine himself stressed the importance of the neophyte’s profession of faith for the efficacy of the sacrament: ‘What is the baptism of Christ? The bath of water in the word. Take away the water; there is no baptism. Take away the word; there is no baptism.’Footnote 41 Augustine describes the baptismal experience quite literally as an immersion in Christian doctrine.

Individuals arguably perceived baptism as transformative and identity-changing. In the fifth and sixth centuries, adult baptism, which required a clear awareness of the sacrament as a choice made by the individual, was practised alongside child baptism and appears to have prevailed in some areas.Footnote 42 Iberian council texts, for instance, characterize baptizands generally as infants in the sixth century at the earliest. The archaeological evidence suggests an even later date for the predominance of child baptism in this region.Footnote 43 Identity-changing experiences are, however, not only confined to adult baptism. Where sponsors stood in for children, they vouched for them, taking on the task of helping them become faithful Christians. The sacrament had also an effect on the self-concept of others besides the baptizand.

The baptismal ceremony effected the transition from the catechumenate, the state of adhering to Christ, to fidelis, the state of being faithful. Technically both the catechumens and the faithful were Christians, but the role which Christianity played (or was supposed to play) in one’s life changed considerably through baptism. This is reflected in the demanding procedures necessary for becoming a fidelis, as opposed to those required to become a Christian. The most outspoken witness we have for the admittance to the catechumenate after the fourth century is again Augustine.Footnote 44 In a letter from c. AD 403, Deogratias, a deacon of the church of Carthage, asked Augustine to instruct him on how to best relate the good news to someone eager to become a Christian. Augustine’s reply, De catechizandis rudibus, provides insight into the missionary work which started from the first encounter between the cleric and the prospective Christian.Footnote 45 This first meeting did not take long. The cleric instructed the candidate about subjects such as the unity of the Old and New Testament, the ideals of the love of God and the love of one’s neighbour, and the necessity of living in accordance with Christian morals.Footnote 46 The candidate was then asked if they believed in these things and wished to put them into practice. If the answer was positive, the candidate received the signatio, a sign of the cross on the forehead, and was henceforth a Christian.Footnote 47

The entry to the catechumenate was relatively undemanding, particularly when compared to the more thorough and rigorous examination which candidates in previous centuries had to undergo. According to the Apostolic Tradition of Hyppolitus, catechumens spent three years in attendance before admission to baptism was granted.Footnote 48 When and where exactly the Apostolic Tradition was written – before AD 235 in Rome, or written and compiled by different authors between the second and fourth centuries – is a subject of debate.Footnote 49 Augustine, in contrast, did not specify any minimum period of preparation required for catechumens to become fideles.Footnote 50 While catechumens were invited to attend sermons like everyone else, we do not have any evidence that their spiritual journey was supervised before they enrolled in the baptismal preparation process held during Lent.Footnote 51 Regular catechetical lessons, examinations of candidates’ preparedness, and fasting and abstinence from a variety of things are recorded for the Lenten preparation only.Footnote 52 For Augustine’s time, a procedure designed to help with the process of inner transformation required by baptism is testified to only after catechumens had signed up for baptism. As a consequence, it seems that popular opinion held that it was necessary to make a distinction between the seriousness of catechumens and that of the faithful, as Augustine himself reports: ‘Let him be, let him do as he likes; he is not baptized yet.’Footnote 53

The sacrament of baptism was the once-in-a-lifetime transition from the old life into the new Christian one and the official celebration of admission into the circle of the faithful. It was also the first instance of a public profession of belief in Christian doctrines. In late antiquity, the ceremony of baptism was enacted as a central event in the formation of Christian identity – perhaps even more so than in the early days of Christianity due to the fading importance of the catechumenate. The baptismal space is a place of Christian identity construction.Footnote 54

In this regard, the decision of some communities to surround neophytes during this rite of passage with imagery recalling a cultural sphere which Christian orthodoxy demanded be left behind must have surely been significant. But how can we make sense of visual and material culture to better understand how Christians constructed their identity?

‘Lived Religion’ and the Study of Visual and Material Culture

Students of late antique baptism and baptismal art find themselves in a dilemma: catechetical and mystagogical literature seems to promise the most immediate and detailed glimpses into a remote ritual practice, yet it also provides us with the normative and universalist perspectives of Christian writers which we originally sought to pit local customs against. To counterbalance this, the case studies in this book focus on gaining information from the material culture on site.

In doing so, I try to avoid taking works of art as expressions of a preconceived shared understanding of religious values. Instead, I start from the assumption that imagery and space are constitutive of both the creation and negotiation of group identities within (religious) groups.Footnote 55 The formation of a group’s religious identity is a discursive process which needs reconfirmation through cultural practices, for example, language or the use of material culture.Footnote 56 Images, architectural settings, places, and situatedness within landscape all give visibility to the characteristics and aims of a given community. These visual and spatial settings, created at some point in time, enter an interactive process of transformation, replacement, and reuse. People react to the buildings in a given place by formulating visions of what their religious environment should be like. At the same time, their notions are predefined and limited by the built environment. Imagery and architecture are not just receptive of the community’s ideas about their religious environment; they also form the community.

Shaping, living with, and altering built environments are all part of the lived practice of religion. This book is inspired by efforts in the study of religion and archaeology to establish ‘lived religion’ as a category of investigation.Footnote 57 This ongoing project reflects the wish to free the study of religion from a fixation on belief as the defining quality of religion, which ultimately derives from a Christian, and especially Protestant, bias.Footnote 58 The ‘lived religion’ approach takes the actual experiences and practices of religious persons as key indicators for what religion is. This is not synonymous with disregarding the religious beliefs a person might hold; it merely shifts the emphasis of our observation to the individual and situational character of all religious experience and practice.Footnote 59 That said, ‘lived religion’ does not project complete individuality onto religious experience; rather, it accepts that ‘people construct their religious worlds together’, for instance by performing rituals or building and using religious spaces.Footnote 60

The study of Christian identity construction stands to benefit from a material focus.Footnote 61 However, while the attention to objects, images, spaces, clothing, or food has begun to transform academic discourse in the study of religion, methodological approaches which can do justice to this ‘mute’ body of evidence are still in their infancy.Footnote 62 Especially Chapters 1 and 2 contribute to this area of research. They interrogate the material and visual culture of the sites studied in this book for information about the lived religion of the communities who built and used the sites. The visual analysis of the baptismal decoration plays a key role in this investigation. The chapters examine how access, circulation patterns, and sightlines predetermined the experience of baptismal decorations; how ecclesiastical and profane buildings flanking the baptisteries extended the ways baptismal space was used; and how the reuse and reframing of pre-existing structures helped shape the perception of the baptismal space.Footnote 63 Chapter 3 is an iconographical study which draws on textual analysis. As in the previous chapters, I will privilege the site-specific evidence.

At the outset, the limitations of researching the interplay between art, architecture, and identity formation must be clearly stated. Studying the conditions under which Roman material culture occurred in baptisteries informs us about the sensory frames provided for individual responses but cannot give us insight into users’ reactions. As individual responses to material culture are not discernible, the study of material culture thus forces us to talk about an anonymous collective of recipients. Moreover, the archaeological evidence provides ample material for sharpening our understanding of religious practices, but it is difficult to isolate religious beliefs from practice.Footnote 64 These limitations, however, should not discourage inquiry into religious practices by way of material culture. How religiosity is expressed is highly significant for the religious experience of individuals, and this is certainly no less valid where religious practices deviated from what might be considered normative today.Footnote 65 But how can an analysis of baptismal art of pre-Christian origin help us understand how Christians in the fifth to seventh centuries reconciled Roman and Christian identities?

Roman Visual and Material Culture in the Baptismal Sphere

The period of investigation overlaps with the cultural and social changes which marked the disintegration of the late western Roman Empire.Footnote 66 The establishment of Barbarian kingdoms in the western Mediterranean, the Visigothic Kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa, and the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy led to processes of diversification across the interconnected Mediterranean.Footnote 67 Ethnically diverse societies transformed the Roman world, increasingly blurring the boundaries between indigenous and migrating populations. As a result, the role which ethnicity played for the identity of migrating peoples has received much attention.Footnote 68

What constituted Roman identity in the post-Roman western Empire, however, is a question which has only recently begun to be asked with fervour.Footnote 69 Walter Pohl suggests differentiating between different modes of late antique Roman identification which can but do not have to determine Roman identity.Footnote 70 Pohl proposes categories as diverse as urban, political, legal and civic, military, territorial, imperial, cultural, religious, and ethnic Roman identities.Footnote 71 This view allows Romanness to mean many different things in different places and for different peoples.Footnote 72 It also helps increase our awareness of features of Romanness which might have been identifiable as Roman longer than others.

This study is predominantly concerned with an aspect of Roman identity often considered exceptionally long-lived: cultural Romanness, or more precisely the use of Roman art and material culture. While political and legal definitions tend to be discussed as being increasingly irrelevant from the fifth century onwards, Roman literary and artistic culture are driving factors for identifying with Romanness in late antiquity.Footnote 73 A shared education, literature, and language are the markers of Roman identity most commonly referred to by scholars, with special attention given to elites, including Barbarian elites.Footnote 74 Upper social strata not only cherished classical art in the domestic sphere but are also seen as the motor behind the assimilation of Roman pre-Christian iconography in Christian art.Footnote 75

It should be pointed out that Roman culture is explicitly not treated as an elite phenomenon in this study.Footnote 76 Instead, by culture I mean any continuously evolving process of a group of people engaged in creating a shared identity.Footnote 77 This can include fleeting expressions of Romanness, such as ways of behaving publicly and structuring social life, including dining, festivals, and dress. The art and architecture dealt with in this book clearly targeted all Christians irrespective of their social standing.Footnote 78 Profound classical learning was barely required to relate to the iconographies discussed.

Deciding what defines material culture as ‘Roman’ in post-imperial Rome, however, remains a challenge.Footnote 79 What do we consider? The techniques of production, style, and subject matter, or the ambition and civic, ethnic, or cultural background of the craftsman, of the commissioner, of the users?Footnote 80 To go with all of these criteria would mean losing any clear sense of what the term ‘Roman’ implies in the utterly Romanized late antique societies. From a certain point of view, we may argue that virtually every Christian building addressed in this book is more or less rooted in Roman art and architecture and could therefore be labelled ‘Roman’. Indeed, the church’s crucial role in the continuity and transformation of classical Graeco-Roman heritage in the post-Roman period is well established.Footnote 81 However, with this loosest possible sense of the term in mind, little is won if we want to obtain insights into the self-concept and the lived religion of late antique Christians from the material and visual culture they used.

Miguel Versluys has lucidly advocated abandoning any notion of Roman art as the style of a nation-state or identifying what is Roman in a given artefact solely on the basis of stylistic or material properties. Such an approach does not do justice to the great connectivity character of the Mediterranean and Near Eastern pre-modern cultures, a character which led the successor culture of Rome to develop an immensely aggregative approach to art, nor does it account for the contextual construction of meaning. With the adaptation of the Mediterranean cultural koine for the specific purposes of local contexts, formerly attributable styles, materials, iconographic elements, and so forth lost original meanings and geographical associations and received new ones.Footnote 82

Instead, Versluys champions an approach to art and material culture which investigates the ‘cultural affiliations’ a style or element carries, that is, those aspects which constitute their belonging to a given culture or cultures in the eyes of the beholder.Footnote 83 Cultural affiliations are not inherent properties. Individual or collective attributions and ways of handling imagery and objects endow them with meaning, and cultural significance is one part of this.Footnote 84 The interpretative level of cultural connotations has come to prominence in the context of art-historical globalization studies.Footnote 85 How viewers associate objects or images with a particular culture – thereby defining them as foreign or familiar, as representative of something outside or within their own culture, or both – is a question highly relevant to the study of the material cultures of interconnected societies. However, it is worthwhile to use the concept of cultural connotations in the field of late antique art more broadly, as this concept is not only of interest in border zones but also crucial in times of cultural transition.

In this book, only such cultural affiliations with Rome which can be relatively safely assumed to have existed in the minds of many late antique Christians will serve as initial indicators that baptismal imagery could have been associated with ‘Roman’ culture. I am thinking of imagery alluding to institutions and practices which, in late antiquity, are still strongly anchored in Roman tradition. More precisely, these are circus games, bathing culture, and mythology. The selection of these institutions and practices depends entirely on the characteristics of the imagery found to adorn baptismal spaces in the western Mediterranean region. I will ask about the role such imagery played in a given baptismal space, and how the Christian community dealt with their Roman heritage more broadly. I will further examine the contexts in which similar imagery was displayed outside of the Christian realm, and whether late antique viewers could have been acquainted with these other settings. As we shall see, many of the Roman traditions which baptismal art alluded to were either still actively practised or relatively fresh in the memory of fifth- to seventh-century Christians.

Granted, ascribing indiscriminately monolithic cultural affiliations to the objects of study would defeat the purpose, as it would not differ from ascribing one-dimensional orthodox Christian meanings to them. Therefore, in each case study I will explore which other possible meanings the respective imagery might have held beyond its cultural affiliation with Rome, both on a local and on a more global level. Moreover, as viewers’ ability to detect Roman cultural affiliations arguably decreased over time, at later stages of a baptistery’s use we need to differentiate, if possible, between consciously undertaken maintenance of Roman material culture and preservation for practical reasons (see Chapter 2).

By investigating to what degree Christian communities associated baptismal art not only with Christian but also with traditional Roman culture, we will encounter material and visual culture which is in a more or less open conflict with the customs and values of the Christian church. Confronted with images of this kind in a church space, uncertainty about their religious significance arises. Was an image considered Christian when placed in a Christian religious setting? Was it associated with the past? Was this past understood as Christian, Roman, or pagan? Were Romanness and Christianness essentially considered the same thing? Did an image lose its affiliation with the past when it was integrated into the Christian sphere?

A central question of the study is whether baptismal art confirmed Roman and Christian identities simultaneously. To put it simply, did baptismal art encourage baptizands to think that by entering the circle of the faithful, they also confirmed that they were Romans? Another guiding question is whether Christians’ affirmation of and identification with Roman popular culture had an impact on their definition of what it meant to be a Christian. Is it possible that baptismal art, at times, was less orthodox than we think due to Christians’ indebtedness to Roman culture? At various points in this book, I will answer both of these questions in the affirmative. Additionally, I will discuss the baptismal imagery of the Orthodox baptistery of Ravenna as an example of a carefully crafted orthodox response to such questions by a member of the clerical elite.

Structure and Geographical Scope

Each chapter of this book illuminates a different aspect of affiliation with Roman culture in the baptismal space: the use of Roman stock imagery and the contemporaneous absence of explicitly Christian imagery (Chapter 1), the occurrence of so-called pagan iconographies (Chapter 2), and the integration of antique personifications in the guise of Roman deities within Christian narrative scenes (Chapter 3). The diversity of the Christian communities tackled in this book shows that the integrative force of Romanness appealed to rural and urban Christians alike, to Christians of a range of confessions, and potentially to people of different ethnic backgrounds as well.

Chapter 1 reinterprets the natural imagery on the floor mosaic of the baptistery of Cuicul in the Roman province of Numidia (today Djémila in north-eastern Algeria) as bare of any univocally Christian messages. Cuicul’s Christian community was indebted to traditional Roman ways of life and ritual practice and maintained elements of this tradition in their religious life as Christians. The chapter argues that the Christian community was so profoundly Roman that its initiatory space did not need to be differentiated from other Roman institutions by its interior decoration. The desire to be distinguishable from non-Christian architecture through specifically Christian symbolism seems simply not to have existed. At the peak of what is known as the Donatist controversy, the Nicene community of Cuicul chose to blend in with traditional private and civic Roman visual culture.

Chapter 2 examines three Christian communities in southern Lusitania (today Algarve and Baixo Alentejo in Portugal) and Africa Proconsularis (today north-eastern Tunisia) of which two or possibly all three used baptismal iconographies pertaining to Graeco-Roman myths and civic cultural practices. The chapter demonstrates that the iconographies alluded to Roman cultural practices that were rejected by ecclesiastical elites. They provided avenues for expressing Christian identity while still allowing an association with traditional Roman culture. Through baptismal art, the Christian communities handed down a local understanding of Christian identity which deviated from the orthodox mainstream. The ethnic identities of the Christian communities cannot be determined for any of the communities. The extent to which the communities were affected by the arrival of the Vandals or Byzantines in the province of Africa Proconsularis or by the Visigoths in Lusitania is likewise unclear. In any case, fundamental shifts in the political landscape evidently did not hinder them from feeling connected to Roman culture.

Chapter 3 re-examines the probably best-studied late antique baptismal work of art, the cupola mosaic of the Orthodox baptistery in Ravenna (c. 451–473), and the cupola mosaic modelled after it in the Arian baptistery nearby (c. 500). The chapter focuses on the representation of the River Jordan at Jesus’ baptism in the form of a Graeco-Roman river personification reminiscent of a river god. The chapter argues that the Nicene bishop Neon was inspired by a sermon of his predecessor Chrysologus, when he chose to personify the River Jordan in the shape of an antique river deity revering Christ. This type of representation fitted well with Chrysologus’ interpretation of the river as a convert to Christianity. However, by visualizing the sermon in this way, Neon added a new layer of meaning to Chrysologus’ textual template. The cupola mosaic no longer showed only the conversion of the River Jordan but also a representative of pre-Christian antiquity accepting the greater truth of Christianity.

The visual rendition of the same scene in the Arian baptistery accentuates Jordan’s classical appearance in the guise of a river god, nourishing the suspicion that Ravenna’s Arian commissioners were particularly keen to comment on the beneficial connection between Christianity and the classical world. It seems that the Arian baptistery surpassed the Orthodox model in its praise of antiquity. This new reading of Ravenna’s dome mosaics makes them outstanding cases of conscious visual commentaries on Christianity’s inclusive relation to the pre-Christian Roman past.

Throughout the book, comparisons with eastern Mediterranean art and architecture and the demonstration of interdependence with developments in the eastern church will draw out how the baptisteries discussed here are – beyond all local particularisms – nourished by a shared Graeco-Roman culture which transcends the late antique and early medieval East and West.

A case in point is of course Ravenna, the western capital of the still united Roman Empire, where the orientation towards Constantinople is observable in virtually every domain, including art and politics.Footnote 86 Ravenna’s baptismal art is an exemplary illustration of this tendency, as the creation of the hitherto unattested iconography in the cupola mosaic of the Orthodox baptistery is best explained by its indebtedness to exegetical literature written in Greek.Footnote 87 However, even baptisteries created in the far West of the Mediterranean show similar tendencies. For example, the closest comparison to the Numidian habit of attaching bathhouses to baptisteries, which will be discussed at length in the next chapter, is to be found at the pilgrimage site of Abu Mena in Egypt.Footnote 88 Furthermore, the mosaics covering the cryptoporticus of the supposed baptismal complex I in Mértola, Portugal, which is geographically closer to the Atlantic than to the Mediterranean Sea, share their closest iconographic resemblance with the mosaic floor of the Diaconicon baptistery on Mount Nebo in Jordan (Figure 2.29).Footnote 89 Such parallels may at times be coincidental. However, strong evidence that the mosaicists in Mértola originally came from Byzantine North Africa, possibly via the Balearic Islands, is an important reminder of the extensive interconnectedness of the Mediterranean.