1. Introduction

At the time of the publication of Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit (Knight, Reference Knight1921), Wesley Mitchell wrote in the American Economic Review that the theory ‘ is not less valid to the realistic economist than to the pure theorist’ (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1922: 275). G. P. Watkins also reflected on Knight's seminal book by emphasizing several key aspects of Knight's distinction between risk and uncertainty, especially in terms of its explanation of business profit. Knight further extended the core ideas in the book revolving around uncertainty and risk in his two Harvard lectures on ethics and economics (Knight, Reference Knight1922, Reference Knight1923) and the economics textbook, The Economic Organization (Knight, Reference Knight1933).

Knight's ideas translated classical liberalism's appreciation for market exchange into neoclassical theory. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit provided a blend of Wicksteed's Common Sense and the Austrian school, concluding that the entrepreneurial response to uncertainty as the key to understanding profit. The recent study of Hudik and Bylund (Reference Hudik and Bylund2021) highlight the role of Knight's (Reference Knight1921) work in balancing between the individual and historical specificity that has been traditionally emphasized by historical schools and institutionalists. Authors demonstrated that the usefulness of general theory differs depending on the nature of the studied phenomenon and, therefore, also across fields of study. For Knight, an important idea emerged from this perspective. At the center of markets are enterprises and entrepreneurs that coordinate the exchange of services for individuals. Individuals do not exchange with each other directly but rather through intermediaries. Hence, modern capitalism includes a variety of entrepreneurs who recognize market opportunities and establish firms as well as enterprises as professionally managed organizations distinct from their founders.

Thus, the extant literature provides both theoretical (Alvarez and Barney, Reference Alvarez and Barney2005, Reference Alvarez and Barney2007; Baumol, Reference Baumol2010) as well as empirical evidence concluding that uncertainty is a prima facia force underlying and motivating entrepreneurship (Alvarez and Barney, Reference Alvarez and Barney2005). However, Braunerhjelm et al. (Reference Braunerhjelm, Ding and Thulin2018) point out and provide empirical evidence that uncertainty can also trigger knowledge spillover within the organizational boundaries of an incumbent firm through intrapreneurship. The literature is remarkably silent on the relative importance of intrapreneurship versus entrepreneurship as the locus for knowledge spillovers.

The purpose of this paper is to fill this gap in the literature by explicitly identifying the extent to which knowledge spillover spurs innovation within the organizational boundaries of an incumbent organization through intrapreneurship, or by contrast through entrepreneurship. We draw on a rich literature to posit that certain knowledge contexts are more conducive to entrepreneurship as a response to uncertainty, while others are more conducive to intrapreneurship.

The knowledge spillover of entrepreneurship is the most significant form of action under the condition of uncertainty. According to the knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship (KSTE), not all knowledge generated by organizational investment in knowledge can be fully appropriated and commercialized within an organization (Acs et al., Reference Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch and Carlsson2009). Due to uncertainty related to knowledge appropriation, development, and market demand for products and services, not all knowledge that is created within organizational boundaries will be utilized by an organization providing a rich repository of entrepreneurial opportunities, which have a high propensity to spillover for commercialization by individual employees who may decide to start a new venture (Audretsch and Belitski, Reference Audretsch and Belitski2013; Audretsch and Keilbach, Reference Audretsch and Keilbach2007). Entrepreneurs use new knowledge under the condition of uncertainty as the prime source of entrepreneurial opportunities (Braunerhjelm et al., Reference Braunerhjelm, Acs, Audretsch and Carlsson2010). More importantly, unlike intrapreneurs who spillover knowledge within organizational boundaries, entrepreneurs are risk-takers and possess a greater capacity to meet the uncertainty by using the underutilized knowledge to innovate and introduce this innovation in the market by starting a new venture – the action known as the knowledge spillover entrepreneurship (Acs et al., Reference Acs, Audretsch and Lehmann2013). As Knight (Reference Knight1921: 309) noted ‘The true uncertainty in organized life is the uncertainty in an estimate of human capacity, which is always a capacity to meet uncertainty’.

Two streams of literature together explain the mechanisms behind the knowledge spillover entrepreneurship: the knowledge filter and entrepreneurial judgment. Knowledge filter is described as ‘the combination of factors preventing or constraining spillovers and as “a semi-permeable barrier limiting the efficient conversion of new knowledge into economic knowledge”’ (Acs and Plummer, Reference Acs and Plummer2005: 442). These factors may originate within the organizational boundaries and as environmental factors preventing individual's uncertain entrepreneurial action. Entrepreneurial judgment relates to an individual's decision whether to pursue or not an uncertain entrepreneurial action, given their subjective assessment of the relative risk-return profile (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015) and the combination of external factors preventing or constraining spillovers (Acs and Plummer, Reference Acs and Plummer2005). Individuals who decide to pursue an uncertain action via entrepreneurship serve as a ‘mechanism that reduces the knowledge filter’ and as a conduit for the spillover of new knowledge (Acs et al., Reference Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch and Carlsson2004: p. 23). This study makes two important contributions to the literature. First, drawing on Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit (Knight, Reference Knight1921), we explain the role of uncertainty and entrepreneurial judgment in the KSTE. In doing so, we assess the relative importance of entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs for facilitating knowledge spillovers and extend Acs and Plummer (Reference Acs and Plummer2005: 442), who state that ‘those willing and able to penetrate the filter to enable knowledge spillovers are (a) incumbent firms and (b) new ventures’.

Second, and more significantly, we use the organizational and environmental context as an empirical lab that can either facilitate or impede knowledge spillovers by changing an individual's subjective assessment of the relative risk-return profile (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015) and thus the propensity for entrepreneurship to serve as a conduit for the spillover of new knowledge. Rather than a ubiquitous response to uncertainty, as has been portrayed by the extant literature, the entrepreneurial response to uncertainty in the form of opportunities for the spillover of knowledge is instead influenced by the knowledge context of the specific organization and an environment. It will shape whether or not the knowledge is commercialized within the organizational boundaries of the incumbent firm through intrapreneurship or through entrepreneurship.

Although uncertainty, according to the KSTE, is one of the causes of knowledge filters, it is not the only one. Entrepreneurs are subjected to the influence of the organizational and institutional environment in which they operate. The organizational and institutional setups are regarded as important factors that are expected to change the size of the knowledge filter (Braunerhjelm et al., Reference Braunerhjelm, Acs, Audretsch and Carlsson2010; Stenholm et al., Reference Stenholm, Acs and Wuebker2013). Acs et al. (Reference Acs, Audretsch and Lehmann2013: 761), for instance, state that ‘Regulations and legal restrictions may account for some of the knowledge filter’. Knowledge spillovers are constrained by the effectiveness of legal institutions such as protection of intellectual property as well as the quality of regulation, entrepreneurial norms, and cognition (Stenholm et al., Reference Stenholm, Acs and Wuebker2013). Therefore, to provide a clearer and more comprehensive understanding of how knowledge spills over through given their subjective assessment of the relative risk-return profile by entrepreneurs (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015), it is important to explore the extent to which the organizational and institutional environment may emerge as a knowledge filter for entrepreneurs.

We use a large-unbalanced panel of 9,126 firms in the UK constructed from an innovation survey and annual business registry during 2002–2014 to test the hypotheses that the entrepreneurial response to uncertainty is influenced by the knowledge conditions specific to the organization. Our finding suggests that entrepreneurs embrace uncertainty to innovate and that knowledge spillovers are greater for startups than through intrapreneurship within incumbent firms.

2. Theoretical framework

Knightian uncertainty, entrepreneurial judgment, and innovation

Much of the entrepreneurship research literature has built upon Schumpeter, Knight, and Kirzner's insights, each of whom has inspired a distinct strand of entrepreneurship theory and application (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015). Although Schumpeter has seen entrepreneurship as an economic activity aiming at the creative disruption of the market, Kirzner identified and developed the best-known concepts of ‘opportunity discovery’ (Klein and Bylund, Reference Klein and Bylund2014) in entrepreneurship in his book ‘Competition and Entrepreneurship’ (Kirzner, Reference Kirzner1973). Knight's idea of entrepreneurship as a judgmental decision-making under uncertainty (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015) constitutes the process of creating, owning, controlling, and combining heterogeneous assets by an entrepreneur to produce goods and services in pursuit of economic profit.

The ‘opportunity discovery’ approach to entrepreneurship (Kirzner, Reference Kirzner1973) is around why entrepreneurial opportunities arise; how entrepreneurs and firms discover and exploit them; and finally, why and when different modes of action are used to exploit those opportunities. Although entrepreneurship research on opportunity discovery enables us to answer why, when, and how opportunities arise (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2012, Reference Foss and Klein2015) yet, in practice, there is little evidence on the link between opportunity discovery and exploitation of opportunities as well as whether these opportunities objectively exist, or they need to be created by entrepreneurs endogenously? (Alvarez and Barney, Reference Alvarez and Barney2005, Reference Alvarez and Barney2007). Authors distinguish two types of entrepreneurs. The first type is a ‘Discovery entrepreneur’ who predicts risks and develops response strategy and action. The second type (Alvarez and Barney, Reference Alvarez and Barney2007) named ‘creation entrepreneurs’ apply iteratively, often incremental decision-making is comfortable with uncertainty and flexible strategies.

Drawing on Knight's (Reference Knight1921) work follows by Casson (Reference Casson1982), this groups of scholars challenge the notion of opportunities. The important book ‘Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment: A New Theory of the Firm’ (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2012) rebuilds Knight's ‘judgment-based view’ by conceptualizing entrepreneur who makes decisions under market uncertainty. Authors discuss when, how, and why entrepreneurs would combine heterogeneous assets to create new knowledge and new products to pursue economic profit. Although markets are uncertain and volatile, it is almost impossible to pursue opportunities without taking risks of losses, which only realize ex-post of market innovation. Entrepreneurs judge market opportunities combine resources and take risks (Knight, Reference Knight1921), and avoid losses by anticipating market conditions. The judgment-based view introduced by eminent scholars Foss and Klein (Reference Foss and Klein2012, Reference Foss and Klein2015) does not evaluate entrepreneurial opportunities, rather than demanding an entrepreneur to adopt a ‘doer’ mentality and seek to take action (Klein, Reference Klein2008; McMullen and Dimov, Reference McMullen and Dimov2013).

Most importantly, the judgment-based view has been widely adopted because it linked entrepreneurs to ownership and appropriation of new knowledge. Knight (Reference Knight1921) argued that judgmental decision-making is inseparable from responsibility, which is seen as the link between an entrepreneur, ownership, and direction of action. By taking responsibility for innovation decisions and market, interventions entrepreneur faces uncertainty and needs to be comfortable (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015; Klein, Reference Klein2008).

Klein (Reference Klein2008) clarifies that entrepreneurship was traditionally understood by economists as a generalized function of ownership, responsibility, market-entry under risk and uncertainty, and innovation. Innovation is associated with an entrepreneurial firm's notion – one that is new, venture-funded, rapidly growing, technology-oriented, and bears uncertainty differently from incumbent firms (Alvarez and Barney, Reference Alvarez and Barney2005).

Radical or disruptive innovations are most often associated with new technologies or business models (Si et al., Reference Si, Zahra, Wu and Jeng2020); they come from new knowledge and entrepreneurial judgment. Snihur et al. (Reference Snihur, Thomas and Burgelman2018) define disruptive innovation as a process in which a startup with few resources can effectively challenge an established business. Radical innovation is defined as ‘a new product that incorporates a substantially different core technology and provides substantially higher customer benefits relative to previous products in the industry’ (Chandy and Tellis, Reference Chandy and Tellis1998). Radical innovation changes can change the products that mainstream customers use (Padgett and Mulvey, Reference Padgett and Mulvey2007).

Entrepreneurs must exercise entrepreneurial judgment to combine heterogeneous assets under uncertainty (Foss et al., Reference Foss, Lyngsie and Zahra2015) and create new solutions to industry and markets. As Knight (Reference Knight1921) argued, to exercise responsibility and innovate, the entrepreneur must risk resources by transforming an idea to new knowledge, which is then operationalized in establishing and operating a new business.

Knowledge spillover entrepreneurship and the judgment-based approach

Focusing on the emerging judgment-based approach (JBA) to entrepreneurship, we argue that economics can say much about how the organizational, market, and institutional context shapes entrepreneurial judgment. Foss et al. (Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019) in their seminal work ‘The Context of Entrepreneurial Judgment: Organizations, Markets, and Institutions’, emphasize the importance of the JBA to entrepreneurship as it can explain how the organizational, market, and institutional context shapes entrepreneurial judgment.

The concept of uncertainty (Knight, Reference Knight1921) and entrepreneurial judgment (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015, Reference Foss and Klein2017) are intrinsically connected. Foss and Klein (Reference Foss and Klein2015) define the term ‘judgment’ from the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘The ability to make considered decisions or to arrive at reasonable conclusions or opinions based on the available information; the critical faculty; discernment, discrimination’. Authors relate to this definition similar to Knight's usage of entrepreneurial judgment, while the Oxford English Dictionary refers to judgment as purposeful action under uncertainty, ‘regardless of the decision-maker's skill’ (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015: 9). The main difference between the JBA to entrepreneurship and the KSTE is that the JBA starts with the fact of judgment – the need for entrepreneurs to make decisions about the future without access to a decision rule, opposite to a ‘rational’ behavior under risk (Foss et al., Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019; Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015). For von Mises (Reference Von Mises1949) and Knight (Reference Knight1921), the exact mechanisms of entrepreneurial judgment and the process of how entrepreneurs' beliefs are formed remain a black box.

The JBA is fundamentally about entrepreneurial action, which manifests in investment or in creating a new product by starting a new firm under conditions of uncertainty. The creation of a new firm is not the only action in a set of entrepreneurial activities that an individual can undertake.

Drawing on prior research on entrepreneurial judgment (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2012, Reference Foss and Klein2017; Klein, Reference Klein2008), the main objection is that ‘entrepreneurial opportunities cannot exist until profits are realized, which means that opportunities can be no more than an ex-post construct’ (Foss et al., Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019: 1204).

Foss et al. (Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019: 1204) define the essence of entrepreneurship as ‘the act of committing resources in realizing the plan, that is, investing resources and executing the entrepreneurial plan or project’; they further posit that ‘entrepreneurship proper begins with action, specifically the acquisition, combination, and commitment of resources to the entrepreneur's production plan. This could involve the creation of a new firm but could also be manifest in a new product or new organizational practice, or even in a decision to maintain existing plans or resource deployments’ Foss et al. (Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019: 1204). Therefore, the entrepreneurial act involves the knowledge spillover by starting a new business, but it involves combining and deploying resources to manifest changes in products and processes, introducing new organizational practices, and incremental and radical innovation.

In the KSTE, an entrepreneur responds to uncertainty in the form of a potential knowledge spillover by creating a new venture or undertaking an innovation investment. Both KSTE (Acs et al., Reference Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch and Carlsson2009; Ghio et al., Reference Ghio, Guerini, Lehmann and Rossi-lamastra2015) and the JBA (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2012, Reference Foss and Klein2017) argue that entrepreneurship is shaped by institutional contexts which influence entrepreneurial judgment on a daily basis to commercialize ideas by starting a new firm. The JBA enriches the KSTE by demonstrating that entrepreneurial beliefs and actions are based on the entrepreneur's subjective perceptions about the organizational and institutional environment and the relative-risk assessment to commercialize new knowledge. Entrepreneurs are good at acquiring, combining, reconfiguring, and commercializing resources, but they are also good at starting a new firm in an uncertain environment. Once the results of entrepreneurial action are realized there will be an adjustment stage (Foss et al., Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019) which entrepreneurs are making further choices about the future investment and creation of new products. Knowledge spilling over from organizations and external environment is required for an entrepreneurial judgment. Entrepreneurs embrace uncertainty to transfer new knowledge from organizations where the knowledge was created to market through innovation activity. We hypothesize:

H1: Entrepreneurs respond to uncertainty by creating a new firm to commercialize new knowledge through innovative activity.

The knowledge spillover of intra- and entrepreneurship

Knight (Reference Knight1921) has repeatedly stressed that uncertainty must be taken radically distinct from the more familiar notion of risk. That is why the intrapreneurs and managers in incumbent organizations where knowledge is created are not comfortable with commercializing all of this knowledge as they cannot figure out if the ideas are good or not and are averse to uncertainty. Investment in R&D (Cohen and Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1989) by incumbents enables entrepreneurs to observe and access the residual of incumbent's knowledge (Acs et al., Reference Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch and Carlsson2009) and use it to penetrate the knowledge filter to commercialize knowledge created in incumbent organizations. In accessing external knowledge, entrepreneurs may co-locate within the same region (Audretsch and Feldman, Reference Audretsch and Feldman1996) to reduce the transaction costs of knowledge spillover (Acs et al., Reference Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch and Carlsson2009, Reference Acs, Audretsch and Lehmann2013) or engage in any form of knowledge collaboration activities and project development (Kobarg et al., Reference Kobarg, Stumpf-Wollersheim and Welpe2019). Firm manager-owners, also known as intrapreneurs (Braunerhjelm et al., Reference Braunerhjelm, Ding and Thulin2018) have been recognized ‘central figures’ of the economic system and of the forces which ‘fix the remuneration of his special function’ (Knight, Reference Knight1921: xi).

Drucker's (1989) defines knowledge as ‘information that changes something or somebody – either by becoming grounds for action or by making an individual (or an institution) capable of different and more effective action’ with Malecki (Reference Malecki2010) and Nonaka and Takeuchi (Reference Nonaka and Takeuchi1995) describe the specific conceptualization of knowledge as either codified or tacit knowledge.

The returns to knowledge commercialization are not determined but may be regarded as residual of other knowledge creation and commercialization activity by intrapreneurs. Knight (Reference Knight1921: 280) posits: ‘the entrepreneur's income is not fixed but consist of whatever remains over after the fixed incomes are paid’. The objective of profit maximization depends on an absolute uncertainty in estimating the value of entrepreneurial judgment.

Related to the entrepreneurial opportunity construct, Foss and Klein (Reference Foss and Klein2020: 367) highlight ‘the centrality of uncertainty to the entrepreneurial process and to argue that these attributes are obscured by the opportunity construct. Opportunities can at best be manifested ex post when entrepreneurial outcomes are successful’. Authors join Knight's (Reference Knight1921) and von Mises (Reference Von Mises1949) in questioning the very notion of entrepreneurial opportunities, finding the opportunity metaphor redundant at best and misleading. Entrepreneurial opportunity language misleads scholars into understanding the fundamental uncertainty that encompasses human action (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2020).

As Foss et al. (Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019) and Foss and Klein (Reference Foss and Klein2020), Knight (Reference Knight1921) argued on the centrality of uncertainty and absolute unpredictability of things that may serve as the source of true profit distinct from ordinary rent. Entrepreneurs make a judgment about resources, scientific and technical conditions, consumer preferences, value of incumbents' knowledge as well as their expectations about future profits and growth. In doing so, entrepreneurs' understanding of potential future profits realized by the ability to spillover new knowledge is between ‘rational’ (the knowledge is tested by intrapreneurs) and random behavior (high uncertainty on returns to knowledge spillover). This random component and entrepreneurial judgment, including the past experiences of returns on investment and knowledge commercialization enables entrepreneurs to value the residual of incumbent knowledge and embrace the uncertainty to commercialize it in the market, achieving the innovation premium, compared to intrapreneurs. The access sand availability of residual knowledge created in incumbent organizations is important in making entrepreneurial judgment on transforming this knowledge into innovation. Thus, this process known as the knowledge spillover of entrepreneurship is different from the process undertaken by intrapreneurs, and enabling innovation premium for entrepreneurs due to their judgment under uncertainty. We hypothesize:

H2: Knowledge spillovers are greater for entrepreneurs than for intrapreneurs.

Institutional context and the knowledge spillover entrepreneurship

Prior research on institutions and entrepreneurship has demonstrated that the institutional environment is an antecedent to knowledge filters (Bennett and Nikolaev, Reference Bennett and Nikolaev2020a) and a determinant of entrepreneurs to penetrate these filters in a way of new knowledge creation (Audretsch, Hülsbeck, and Lehmann, Reference Audretsch, Hülsbeck and Lehmann2012; Bennett and Nikolaev, Reference Bennett and Nikolaev2020a, Reference Bennett and Nikolaev2020b; Zhu and Zhu, Reference Zhu and Zhu2017). Institutional environment affects entrepreneurial judgment (Knight, Reference Knight1921) and changes the structure of economic incentives that make entrepreneurs embrace uncertainty and affect entrepreneurs' growth aspirations in different ways (Williamson, Reference Williamson2000). Knight (Reference Knight1921) famously argued that uncertainty creates market opportunities, but the institutional environment affects entrepreneurs' ability to establish business and operate it in pursuit of such opportunity. For Knight, emergent novelty and innovation are in constant tension with institutional context. Although institutions may create an order, they also constrain the emergence of new laws, ideas, and limit human behavior.

Institutional environment includes formal institutions such as regulation and laws as well as informal institutions such as entrepreneurial culture, which gives acceptance and support to individuals attempting to start their own business (Welter et al., Reference Welter, Baker and Wirsching2019). Delving more deeply into institutions, Williamson (Reference Williamson2000) categorizes them into an institutional hierarchy, each level placing constraints on the ones below and this creates a certain knowledge context for entrepreneurs where they exercise their judgment. Welter et al. (Reference Welter, Baker and Wirsching2019: 327) argue that contextualization of knowledge creation activity is important to understand the bigger picture, while Hudik and Bylund (Reference Hudik and Bylund2021) highlight Knight's appreciation of both general principles and historical specificity in understanding institutions, with the balance that Knight struck between the two.

Regional culture conducive to entrepreneurship is known to facilitate economic competitiveness and resilience of regions over time (Fritsch et al., Reference Fritsch, Sorgner and Wyrwich2019). Regional institutions and the culture of entrepreneurship may serve as an antecedent of a knowledge filter, affecting both the relative risks and the willingness of individuals to take such risks and embrace uncertainty (Knight, Reference Knight1921, Reference Knight1933). In this case, historical factors, traditions, and available role models may play a significant role in shaping regional institutions conducive to entrepreneurship (Stuetzer et al., 2016).

Environmental context influences the determinants of entrepreneurs to penetrate knowledge filters (Acs and Plummer, Reference Acs and Plummer2005; Chowdhury et al., Reference Chowdhury, Audretsch and Belitski2019). In places where entrepreneurship is seen as providing valuable rewards and entrepreneurs are seen as role models, a sustainable entrepreneurial culture can be formed. Regions with high quality of institutions may reduce the uncertainty of entrepreneurship activity by organizing operational and transaction costs related to access and processing of new knowledge and building relationship and trust to access incumbents' knowledge (Kobarg et al., Reference Kobarg, Stumpf-Wollersheim and Welpe2019). In an institutional environment that promotes entrepreneurial culture of risk-taking under uncertainty, entrepreneurs may be more willing and able to penetrate the filter to enable knowledge spillovers (Acs et al., Reference Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch and Carlsson2004; Audretsch and Keilbach, Reference Audretsch and Keilbach2007). In regions where the institutional environment is conducive to new firm creation and commercialization of knowledge through innovative activity – more entrepreneurs can penetrate the filter and convert more knowledge into innovation, even under a higher level of uncertainty about the outcomes of such commercialization. Although incumbents calculate risks and insure against it, uncertainty for entrepreneurs paves the way for opportunities to spillover new knowledge if the market adopts innovation, with the effect being greater in the institutional context conducive to entrepreneurship. We hypothesize:

H3: (a) Strong institutional context positively moderates the relationship between knowledge spillover and innovation activity; (b) the effect is greater for entrepreneurs than for intrapreneurs.

3. Data and method

Sample

To test our research hypotheses, we use an unbalanced panel dataset that covers the innovation activity of 9,126 UK firms constructed from six consecutive waves of a community innovation survey (UKIS) and Business Structure Database (BSD) known as Business Register during 2002–2014 and annual business registry survey during 2002–2014. We collected and matched UKIS data to the initial year of BSD data for 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2012. The UKIS includes innovation input and output data, barriers to innovation, innovation mechanisms, innovation sales, R&D and software expenditure, knowledge collaboration, etc. The BSD variables describe the firm's legal status, ownership (foreign or national firm), alliance information (firm belongs to a larger enterprise network), export, turnover, employment, the industry at five-digit level, and a firm location the postcode.

The Business Structure Databases could raise the measurement problem as a significant share of firms registered in the BSD is self-employed with zero employees. Altogether self-employed with zero employees and micro-firms make up to 97% of the BSD sample in different years.

A vast literature models entrepreneurship as occupational choice and assumes that individuals differ in the characteristics that are relevant to perform the entrepreneurial function (Hudik and Bylund, Reference Hudik and Bylund2021). Research focuses on whether actors are self-employed (entrepreneurs) or employed in a firm (non-entrepreneurs or intrapreneurs). For this study, we are interested in researching entrepreneurial firms, rather than self-employed entrepreneurs, and firms that include such characteristics as the ability to respond to opportunities to innovate (Holmes and Schmitz, Reference Holmes and Schmitz1990), the ability to recognize and combine talents (Lazear, Reference Lazear2005), risk aversion, and initial wealth (Kihlstrom and Laffont, Reference Kihlstrom and Laffont1979).

Due to a substantial number of self-employed and partnership-type firms with less than six employees as well as life-style entrepreneurs in the BSD data we excluded them from the sample, if any firm with less than six employees would match. These firms respond to exogenous factors such as uncertainty and risk in a different way. Entrepreneurial activity requires investment in education and training (Hudik and Bylund, Reference Hudik and Bylund2021; Schultz, Reference Schultz1980), thus explicitly linking entrepreneurship with human capital theory (Klein and Cook, Reference Klein and Cook2006). When excluding firms with less than six employees we keep firms that are most interested in growing their business, excluding a significant number of necessity-driven entrepreneurs and occasional new business registry of solo entrepreneurs, if any entered in the innovation survey. Our sample is reduced to 13,712 observations and 9,126 firms.

Given the availability of data, we created two distinctive samples. The first sample includes data on innovation performance proxied by a share of new to market sales (13,712 observations) for firms with at least six employees, which also excludes all self-employed. Our second sample excludes London-based firms or firms that are located elsewhere with the headquarters (HQs) in London with 13,552 observations.

We start by analyzing our sample of 13,712 observations and 9,126 firms. Under-represented sectors are mining and quarrying (<1%) and utility electricity (<1%). Industries with the highest share in a sample are high-tech manufacturing (20.90%), real estate and other business activities (11.44%), wholesale, retail trade (16.72%), and construction (10.45%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Data representation by sector, region and survey wave

Source: Office for National Statistics. (2017a). UK Innovation Survey, 1994–2016: Secure Access. [data collection]. 6th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 6699, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6699-6 (hereinafter UKIS- UK Innovation survey). Office for National Statistics. (2017b). Business Structure Database, 1997–2017: Secure Access. [data collection]. 9th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 6697, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6697-9 (hereinafter BSD- Business Structure Database).

Most of the firms in a sample are from the South East of England (13.47%), Yorkshire and Humber (10.74%), Northern Ireland (12.64%), and West Midlands (9.47%). Firms in Scotland (<4%) and London (<2%) are underrepresented. The industrial and wave composition of firms does not change across the full sample of 13,712 observations, and the sample when London firms are excluded due to only 235 firms are from London. The major differences in the distribution of firms were observed across survey waves 2002–2014. Most of the sample observations come from the first UKIS4 round (2002–2004) – 40.79%, with only 8.52% of firms are found in the 2012–2014 survey.

Variables

Dependent variable

We measure innovation using the following question from the UKIS survey: ‘What is the percentage of the business total turnover of products and services that were new to the market?' The variable varies from zero – which means a firm has zero sales of new to market products, to 100 – all sales from new to market products and has been used extensively as a measure of radical innovation (Audretsch and Belitski, Reference Audretsch and Belitski2019; Kobarg et al., Reference Kobarg, Stumpf-Wollersheim and Welpe2019; Leiponen and Helfat, Reference Leiponen and Helfat2010; Santamaria et al., Reference Santamaria, Nieto and Barge-Gil2009; Snihur et al., Reference Snihur, Thomas and Burgelman2018). It is important to note that the survey asks firms to list the introduction of incremental and radical innovations (OECD/Eurostat, 2005), and our estimates can differentiate between radical and incremental innovations. The variable we use refers to products and services that were new to the market in line with the definition of innovation in prior research (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Grinstein and Harmancioglu2016; Chandy and Tellis, Reference Chandy and Tellis1998; Santamaria et al., Reference Santamaria, Nieto and Barge-Gil2009).

Explanatory variables

Knowledge spillovers. In the questionnaire, firms rated the importance of externally available information for their innovation process from four sources on a four-point scale from unimportant (0) to very important (3). We draw on the work of Cassiman and Veugelers (Reference Cassiman and Veugelers2002), who create a knowledge spillover using information sources such as patent information; specialist conferences, meetings, and publications; trade shows; and seminars. Cassiman and Veugelers (Reference Cassiman and Veugelers2002: 1171) generate a firm-specific measure of incoming spillovers by ‘aggregating these answers by summing the scores on each of these questions and rescaled the total score to a number between 0 and 1.3’.

These external sources of knowledge could be generated by incumbent firms and universities (Audretsch and Link, Reference Audretsch and Link2019), but also at the conferences, trade fairs or exhibitions; professional and industry associations; as well as the knowledge found in technical, industry or service standards; scientific journals and trade/technical publication. We rescale the variable between zero and one. These measures are closely related to each other, with correlation coefficients between 0.53 and 0.75. Our first assumption is that all components are equally important in measuring the knowledge spillover (e.g. information from conferences, patent and publications, events, information from industry or service standards) and for this reason we aggregate and rescale these measures by applying the equal weighting of all four components. Standardizing the construct before estimating a model is also used to reduce potential problems of multicollinearity (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, West and Reno1991). Our second assumption for the knowledge spillover is that active knowledge collaboration between innovators and incumbent organizations is not required. Various sources of knowledge spillover altogether represent substantial knowledge inputs. As part of the robustness check, we aggregate the components of the knowledge spillover with a high degree of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha coefficient = 0.74). Using this construct instead of knowledge spillover in the estimation further does not change the significance of the coefficient.

Our measure captures the exogenous nature of knowledge spillovers, determined by technology and market characteristics of knowledge. Although alternative measures of knowledge spillovers have been proposed in the literature (Audretsch and Belitski, Reference Audretsch and Belitski2020; Keller, Reference Keller2002; Varga, Reference Varga2000), e.g. total pool of external knowledge available, investment in R&D, hiring researchers, these studies relied on the indirect measurement of knowledge spillovers require the construction of a pool of potentially available knowledge within each industry region and for each firm in the sample. Prior measures use to examine the benefits of external knowledge by measuring the geographical and technological ‘proximity’ between incumbents and knowledge receiver – an entrepreneur. Our third and final assumption is that various forms of knowledge inputs that are not geographically constrained (Balland et al., Reference Balland, Boschma and Frenken2015).

Startups. Another explanatory variable we use to identify a startup is firm age. We measure startup as using a binary variable equal to one if a firm is a startup, defined as having a maximum of 4 years since incorporation, has no subsidiaries and is itself a firm and not a subsidiary. The maximum number of employees at the start (year of incorporation) is between 6 and 49. This approach to innovative startups is widespread (Audretsch et al., Reference Audretsch, Colombelli, Grilli, Minola and Rasmussen2020).

Uncertainty and risk. Knight (Reference Knight1921) has repeatedly stressed that uncertainty must be taken radically distinct from the more familiar notion of risk. To measure (1) risk and (2) uncertainty, we use a proxy for the importance of (1) excessive perceived economic risks as constraints on innovation and activities in influencing a decision to innovate (0 – none; 3 – very high) and (2) the uncertain demand for innovative goods or services as a constraint on innovation and activities in influencing a decision to innovate (0 – none; 3 – very high). These factors used in Coad et al. (Reference Coad, Segarra and Teruel2016) to predict the barriers to innovation and form productivity were found to negatively affect the decision to innovate. Given that entrepreneurs embrace uncertainty (Knight, Reference Knight1921) in search of profits, we expect to find uncertainty to be positively associated with innovation for entrepreneurial firms, while the risk is either negative or not significant.

Institutional environment. A body of literature argues that the institutional environment is a determinant of knowledge creation (Bennett and Nikolaev, Reference Bennett and Nikolaev2020a, Reference Bennett and Nikolaev2020b; Zhu and Zhu, Reference Zhu and Zhu2017). A weak institutional environment affects entrepreneurial judgment (Casson, Reference Casson1982; Knight, Reference Knight1921) and changes the structure of economic incentives that make entrepreneurs embrace uncertainty. In particular, the quality of governance is an important concept which is associated with the extern of formal and informal institutions. Williamson (Reference Williamson2000) argues that governance shapes the way that individuals interact, aligning the governance structure they adopt with the types of transactions. Williamson (Reference Williamson2000) places particular emphasis on private governance; for entrepreneurship, this refers to the nexus of formal and informal arrangements, the provision of finance, and the development of networks. Quality of governance index at the NUTS2 level was developed by Charron et al. (Reference Charron, Lapuente and Rothstein2013) and includes corruption and the rule of law. Given the challenges of compatible data across UK regions, we used the European Quality of Government Index (EQI) by NUTS2 regions for the UK during 2009–2017, also used in prior research (Charron et al., Reference Charron, Lapuente and Rothstein2013, Reference Charron, Dahlberg, Sundström, Holmberg, Rothstein, Alvarado Pachon and Dalli2020; Rodríguez-Pose and Garcilazo, Reference Rodríguez-Pose and Garcilazo2015). We interpolated EQI for year 2010 for the periods of 2002–2004, 2004–2006, and 2006–2008, while EQI in 2013 was used for 2008–2010 and 2010–2012; the level of 2017 was used for the period 2012–2014.

Control variables

Appropriability. To obtain some insight into the role of appropriability methods at the firm level, we draw on the responses to a question in the survey on the degree of importance to the firm of different methods of protection from 0 – not important to 3 – crucial. The survey question is similar to those used in previous studies of appropriability methods (Laursen and Salter, Reference Laursen and Salter2014). Based on the responses, we created a measure of the overall strength of the firm's appropriability strategy by aggregating the five measures of formal and strategic protection (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Helmers, Rogers and Sena2013) listed in the survey (scored on a 0–3 scale). The six items are patents, copyright, trademarks, secrecy, first entry, and complexity. We sum the scores on each of these questions and rescale the total score to a number between 0 and 1 to generate a measure of legal and strategic protection. The set of items appears to have a high degree of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha coefficient = 0.89). Previous research has found a positive relationship between appropriability and firm radical innovation, which we expect (Audretsch et al., Reference Audretsch, Colombelli, Grilli, Minola and Rasmussen2020; Laursen and Salter, Reference Laursen and Salter2006).

Absorptive capacity. To control for the level of absorptive capacity, we use three variables. First, firm-level R&D intensity (R&D expenditure divided by total sales) (Cohen and Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1989). Second, firm-level software intensity (expenditure for purchasing advanced machinery, equipment, and software divided by total sales) (Audretsch and Belitski, Reference Audretsch and Belitski2019; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Helmers, Rogers and Sena2013). Third, the share of employees holding a higher education degree (MSc and above) (Kobarg et al., Reference Kobarg, Stumpf-Wollersheim and Welpe2019). An increase in software and R&D intensity, as well as level of education of employees, was found to be positively associated with radical innovation (Laursen and Salter, Reference Laursen and Salter2006).

Firm age and size. We control for a firm size, measured as a number of employees (expressed in logarithms) and firm age, measured as a number of years since establishment (expressed in logarithms). Both variables are expected to have a non-linear relationship between innovation as it diminishes with firm growth and age. A number of employees and firm registration year are taken from BSD data.

Knowledge collaboration. To control for the breadth of openness of new firms, we include additional control measures for whether the firm collaborates or not with external partners on knowledge regionally, nationally, and internationally (Kobarg et al., Reference Kobarg, Stumpf-Wollersheim and Welpe2019; Leiponen and Helfat, Reference Leiponen and Helfat2010). The depth of external knowledge collaboration was found to have a positive effect on firm innovation. By including the geographical dimensions of firm knowledge search, we control for the stylized fact that knowledge may be [regionally] concentrated (Malecki, Reference Malecki2010) and that knowledge flows decay with the distance between knowledge generator and receiver (Audretsch and Feldman, Reference Audretsch and Feldman1996). We also control for the cost of knowledge transmission in collaboration when financial reward may follow, and collaboration may not be ‘costless across geographic space’ (Audretsch and Lehmann, Reference Audretsch and Lehmann2005: 1194).

Other control variables. Furthermore, we controlled for firms' exposure to international markets with the binary variable equals to one if a firm export, zero otherwise (i.e. the share of the revenue from markets outside UK >0) (Belderbos et al., Reference Belderbos, Carree, Lokshin and Sastre2015). Exporters are likely to be more innovative as the competition is more intense in the international market than in the domestic market. We control for factors that may become impediments of innovation e.g. cost of finance, access to finance, a market competition drawing on Hall et al. (Reference Hall, Helmers, Rogers and Sena2013), which are expected to have a negative relationship with firm innovation. Furthermore, we controlled for industry differences by including industry dummies in our analyses. Moreover, we controlled for differences between firms that could take place over the analysis period with the first wave (2002–2004 as a reference category). We control for the differences in local environment and innovation ecosystems across different city-regions by including 128 city-regions fixed effects with York city as a reference category. Finally, firms with different legal status (e.g. partnership, limited liability partnership, etc.) may acquire different initial incentives to innovate with the listed firm as the reference category. We do not hypothesize any relationship between a firm's legal status and the level of innovation.

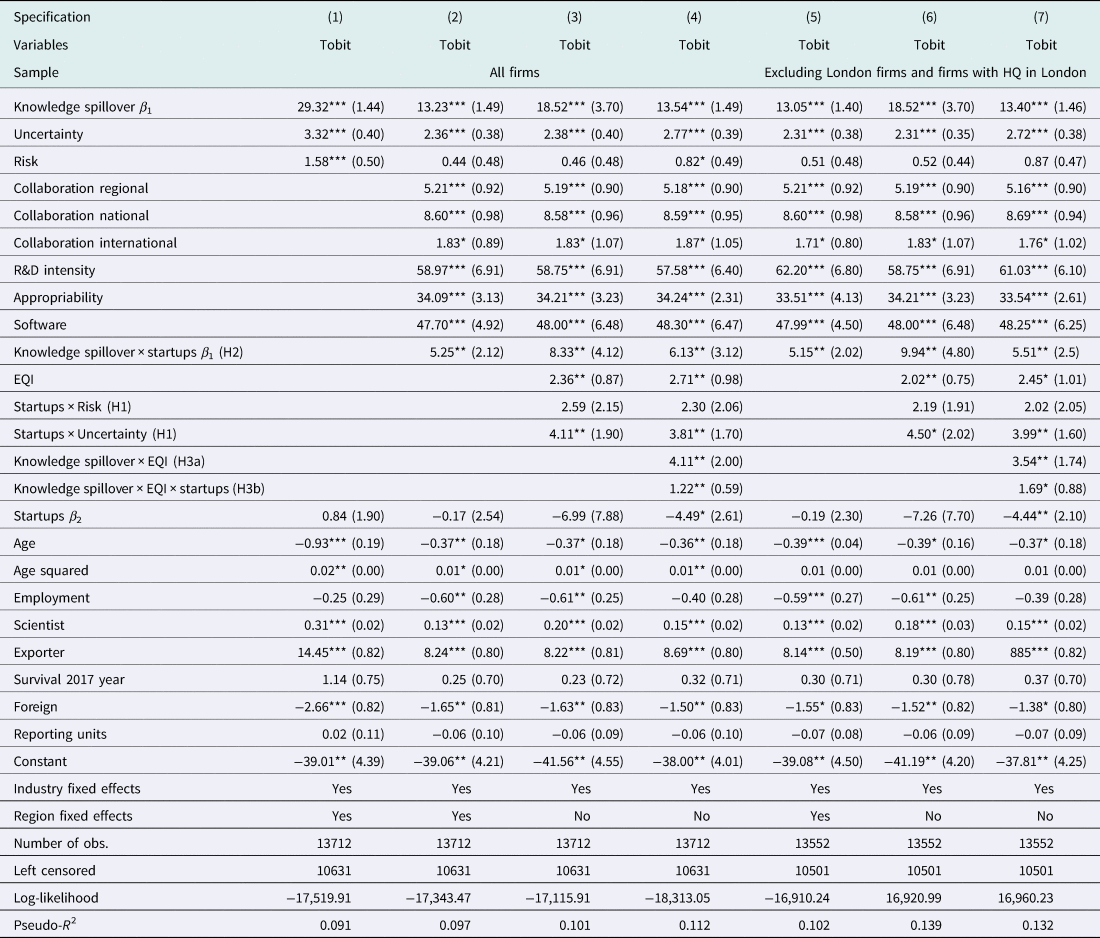

Table 2 provides a list of variables used in this study with the summary statistics presented in Table 3.

Table 2. Description of variables

Source: UKIS – UK Innovation survey; BSD – Business Structure Database.

Table 3. Summary statistics for variables used in this study

Note: Number of observations: 13,712.

Source: UKIS – UK Innovation survey; BSD – Business Structure Database.

Method

In our identification strategy, we account for the censored nature of our dependent variables, employ appropriate measures to identify the hypothesized the relationships, and consider the relationship between our independent variables. First, because of the nature of the dependent variables as censored variable, we use tobit models (Amemiya, Reference Amemiya1985; Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2009). Censoring takes place for cases with a value at or above some threshold (zero in our case). Tobit estimation is the most appropriate as we have a lump of zeros with 77.53% of zero innovation sales observed in our sample (10,631 out of 13,712 observations). In econometric form, the model has dependent variable y it (firm's innovation sales) as a function of a set of explanatory variables startup E it, knowledge spillover S it, uncertainty U it for firm i at time t and institutional environment EQI mt for region m at time t:

We can also call it structural equation to emphasize that we were interested in β 3–β 5 that demonstrate the role of uncertainty for innovation in entrepreneurial firms (β 3), the knowledge spillover for entrepreneurship for entrepreneurial firms β 4. The role of institutional environment for innovation activity of startups is β 5. The vector E it is a startup, the vector S it is a knowledge spillover measure, U it is the vector of perceived uncertainty in demand; EQI mt is the vector of the institutional quality in region m at time t. Vector of parameters of β 6 illustrates a three-way interaction of EQI, startups, and knowledge spillover (Cohen and Cohen, Reference Cohen and Cohen1983). The vector z it is a list of exogenous control variables and not correlated with u it – an error term. a s, a t are industry and year fixed effects. Our knowledge spillover variable S it and market uncertainty U it are exogenous and are unlikely to be correlated with u it (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2009: 517).

We estimate equation (1) using a multivariate tobit model for a sample of 13,712 observations and a reduced sample of 13,552 observations after excluding firms located in the London area and firms with HQs in London. One of the data limitations is that the average number of observations per firm is 1.7. Although we control for a large number of covariates in equation (1) of survey year, industry, and regions, the time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity using fixed effects cannot be removed.

Furthermore, when estimating equation (1) using tobit estimation (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2010) we considered the issue of unobserved heterogeneity. First, we implement several control variables that could, against the background of the literature, account for unobserved heterogeneity. Second, employing the tobit regression exclusively, we deem unobserved heterogeneity not to be a major concern (Kobarg et al., Reference Kobarg, Stumpf-Wollersheim and Welpe2019; Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2010). Finally, we estimated equation (1) using an ordinary least squares (OLS) with industry and year fixed effects as a robustness check.

4. Results

Uncertainty and Knightian entrepreneur

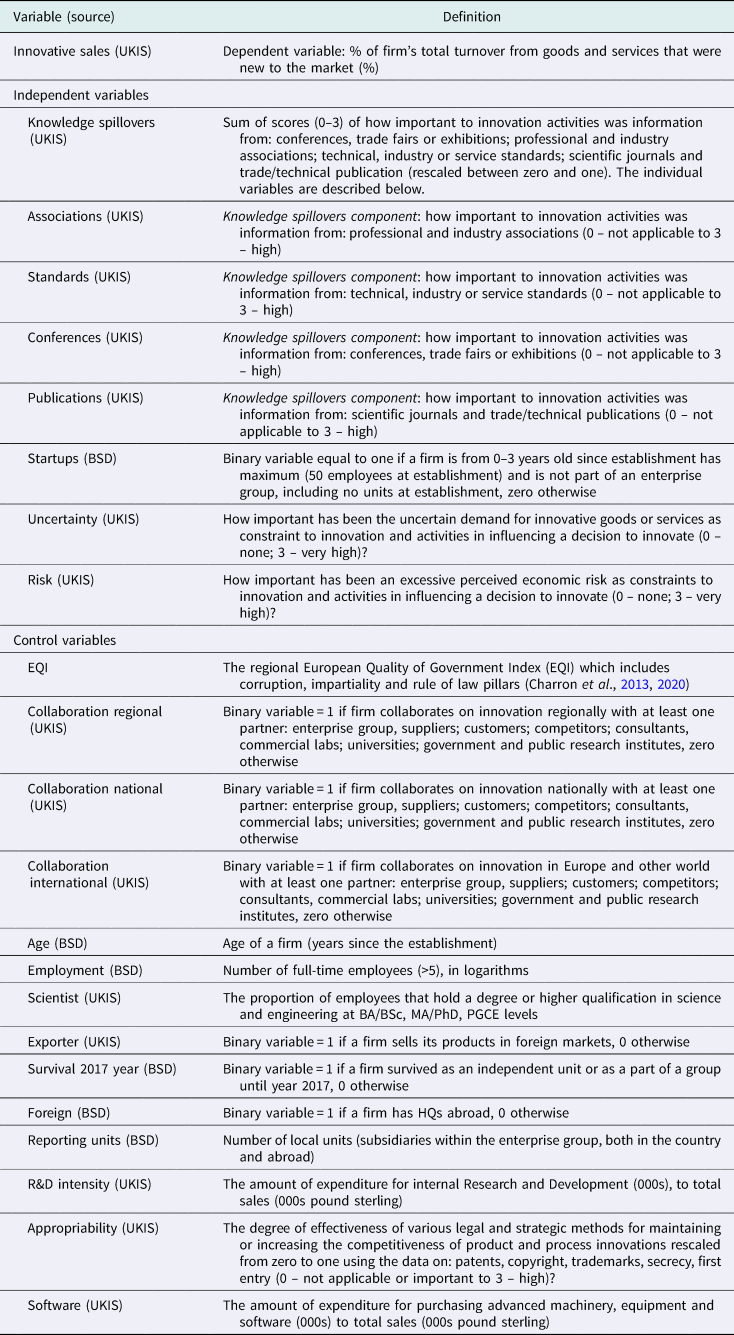

The results of hypotheses testing are presented in Table 4, with a pooled OLS robustness check in Table 5. First, we estimated model (1) using the tobit model of 13,712 observations using the full sample (Table 4, specifications 1–4), and then as part of the robustness check, we excluded London-based firms and firms with HQs in London using the reduced sample of 13,552 observations. We calculated a likelihood-ratio test comparing the panel tobit model with the pooled OLS with the test supporting the use of tobit estimation.

Table 4. Tobit estimation of the knowledge spillover of entrepreneurship

Dependent variable: Innovation sales % to total sales.

Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. The coefficients of the tobit regressions are the marginal effect of the independent variable on the probability of knowledge spillover, knowledge collaboration, ceteris paribus. For dummy variables, it is the effect of a discrete change from 0 to 1.

Significance level: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Note: Reference category for legal status is Company (limited liability company), industry (mining), region (North East of England).

Source: UKIS – UK Innovation survey; BSD – Business Structure Database.

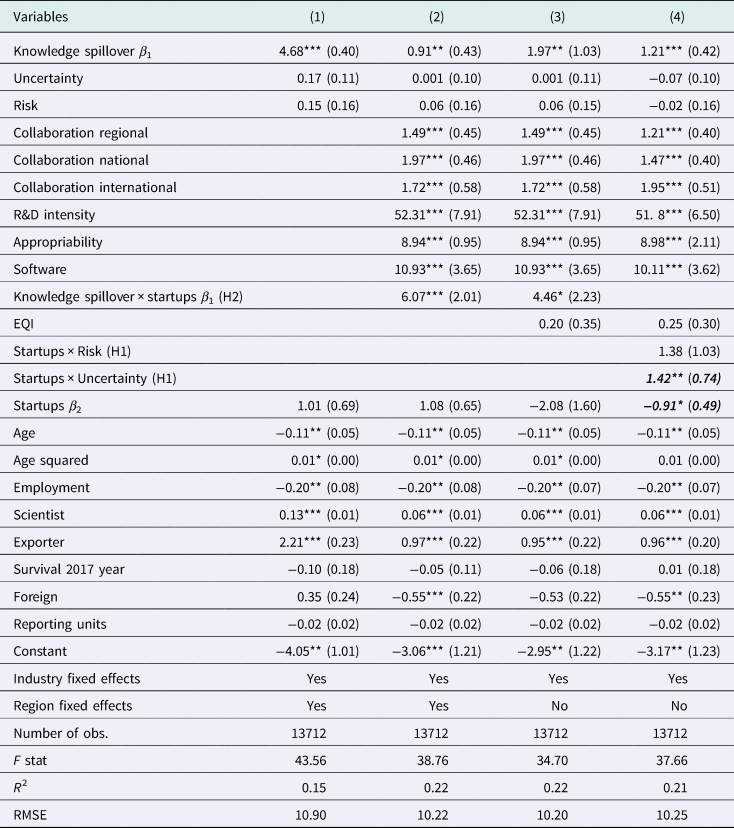

Table 5. Pooled OLS estimation (all firms)

Dependent variable: Innovation sales % to total sales.

Note: Reference category for legal status is Company (limited liability company), industry (mining), region (North East of England). Robust standard errors are in parenthesis.

Significance level: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Source: UKIS – UK Innovation survey; BSD – Business Structure Database.

The coefficients in Table 4 present the marginal effect of the independent variables on firm innovation. Robust standard errors are estimated for these coefficients. Regression (1) includes only control variables as well as knowledge spillover and startup identifier, while regression (2) adds other control variables for knowledge collaboration and absorptive capacity of a firm (Cohen and Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1989; Van Beers and Zand, Reference Van Beers and Zand2014), and regression (3) adds institutional quality (Chowdhury et al., Reference Chowdhury, Audretsch and Belitski2019; Welter et al., Reference Welter, Baker and Wirsching2019) measure with the EQI. Finally, regression (4) tests for the role of the perceived risk and uncertainty in their relationship to innovation, distinguishing both effects between incumbent and startups.

The overall predictive power of the estimated innovation functions (1) and (2) in Table 4 is higher than that in regression (3) when we are controlling for the quality of institutions (Charron et al., Reference Charron, Lapuente and Rothstein2013, Reference Charron, Lapuente and Annoni2019). The predictive power of regression (4) is the highest, which demonstrate the way entrepreneurs respond to uncertainty. Interestingly, that the interaction coefficient of risk and startups is insignificant, while the interaction coefficient of uncertainty and startups is significant and positive. In economic terms, we interpret it as a one unit increase in the level of uncertainty (from low to a medium level, or from none to a low level), increases innovation sales by 3.81% for startups compared to incumbents (specification 4, Table 4). This effect does not change (3.99%) when we exclude London-based firms and firms with HQs in London (specification 7, Table 4), supporting H1. Although uncertainty creates opportunities to innovate new products for both intrapreneurs and entrepreneurs (specifications 1–4, Table 4), the effect is 3.81% greater for entrepreneurs for every unit change in perceived uncertainty.

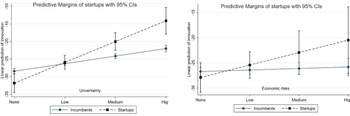

As in the case of full sample estimation, the risk perception by entrepreneurs is not associated with innovation outcomes. Innovation is associated with higher uncertainty and entrepreneurs are able to respond to it as an opportunity while intrapreneurs and incumbent managers are more averse to uncertainty of potential implications of knowledge. Figure 1 plots the predictive margins of innovation sales derived from regression (4) (Table 4) as the average partial effects (APEs). We plotted the APE of the explanatory variables – risk and uncertainty on the expected level of innovation sales. This means taking partial effects estimated by the tobit for each observation (i) and taking the average across all observations. One can clearly see that an increase in uncertainty (medium and high) results in a greater innovation rates in startups than in incumbents, underlying a non-linear relationship between uncertainty and response to it between entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs. Under high level of uncertainty entrepreneurs perform significantly better (Knight, Reference Knight1921). There is no difference in predictive margins of innovation between intrapreneurs and entrepreneurs under the condition of risk (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Perceived uncertainty (left) and economic risks (right) by startups and incumbents and its association with firm innovation.

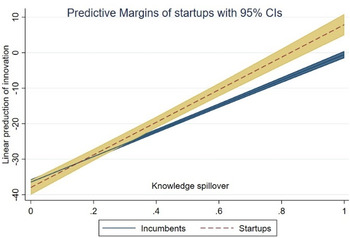

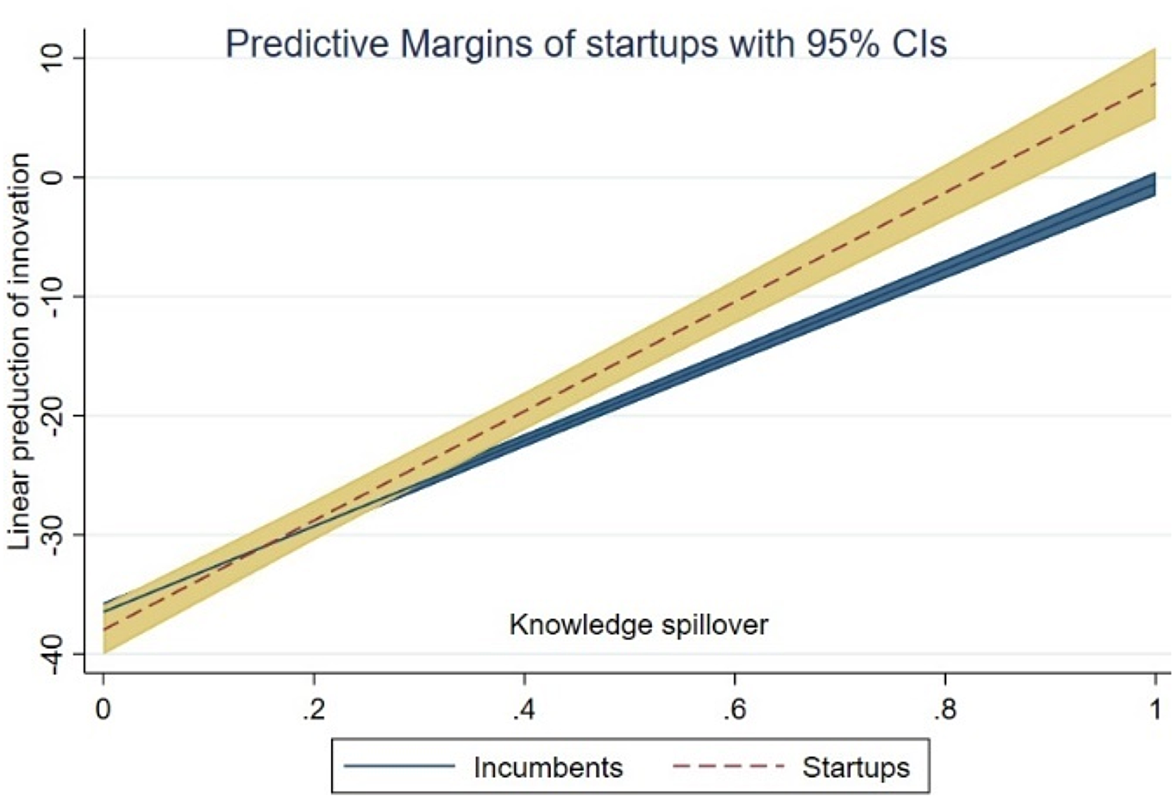

The direct effect of knowledge spillover on innovation is positive (β = 29.32, p < 0.001) while on average innovation sales rate is not different between startups and incumbents, with the startup coefficient is not statistically significant (specifications 1–3, Table 4). Once we add a set of controls for absorptive capacity and knowledge collaboration the coefficient of knowledge spillover drops (β = 13.23, p < 0.001) and the interaction coefficient of startups and knowledge spillover is positive and statistically significant (β = 5.25, p < 0.01) (specification 2, Table 4), what remains positive and significant in specifications 3 and 4 (Table 4). This means that for entrepreneurs, the knowledge spillover has a greater effect on innovation than for incumbent firms supporting H2, which states that the effect of the knowledge spillover is greater for entrepreneurs than for intrapreneurs. In economic terms, this means that a one unit increase in the combined relevance of external knowledge for entrepreneurs is associated with innovation sales increase on average by 18.48% (β = 13.23 + 5.25, p < 0.001), while only by 13.23% for incumbent firms. Figure 2 illustrates the predictive margins of innovation sales for startups and incumbent firms with a clear gap in the innovation performance. This gap between startups and incumbents increases as the size of the knowledge spillover increases. Our hypothesis 2 is supported. Excluding London firms does not change the results for H2.

Figure 2. Knowledge spillover of entrepreneurship.

In order to test our H3a, which states that stronger institutional context in regions increase the knowledge spillover entrepreneurship, we add an interaction between EQI (institutional quality) and knowledge spillover (specification 4, Table 4) with the interaction coefficient positive and significant (β = 4.11, p < 0.01). This finding is robust when we exclude firms located in London with the coefficient remains positive and statistically significant (β = 3.54, p < 0.01) (specification 7, Table 4). This means that for entrepreneurs, the knowledge spillover has a greater effect on innovation in regions with a stronger institutional context supporting H3a. In economic terms, the effect of knowledge spillover differs between regions with different institutional quality as one unit increase in the combined relevance of external knowledge for entrepreneurs is associated with innovation sales increase on average by 17.65% (β = 13.54 + 4.11, p < 0.01) for every unit increase in the EQI, compared to 13.54% in other regions.

When interpreting the results for a model with a three-way interaction (specifications 4 and 7, Table 4), we adhere to Cohen and Cohen (Reference Cohen and Cohen1983) who warn that in the presence of higher-order interactions, the coefficients for the related lower-order terms convey no meaningful information. In specification 4 (Table 4) we observe for the interaction term (knowledge spillover × EQI × startups) positive and statistically significant coefficient (β = 1.22, p < 0.01), suggesting that the startups and institutional quality act as two capabilities and as complements to each other in increasing the effect of knowledge spillover on innovation performance. In other words, we support H3b, which states that in regions with stronger institutions, the knowledge spillover entrepreneurship is greater for entrepreneurs than for intrapreneurs. In specification 7 (Table 4), we observe consistent results with a three-way interaction positive and significant when London-based firms are excluded (β = 1.69, p < 0.01).

Other results

Other factors which increase innovation performance are active collaboration with external partners regionally (β = 5.21, p < 0.001), nationally (β = 8.60, p < 0.001), and internationally (β = 1.83, p < 0.05) (Table 4, specification 2).

The positive coefficient of appropriability demonstrates that firms that legally and strategically protect their innovations (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Helmers, Rogers and Sena2013) also achieve, on average, 33.08% higher innovation sales (β = 34.09, p < 0.001) compared to firms with weaker appropriation mechanisms (specification 2, Table 4). The effect of R&D intensity on innovation is positive (β = 58.97, p < 0.001), which means that 1% increase in R&D intensity is associated with on average 58.97% higher innovation sales. The relationship between software intensity and innovation sales is positive (β = 47.70, p < 0.001), highlighting the role of digital capabilities for innovation.

Entrepreneurial firms, on average, are as innovative as incumbents with the startup coefficient being insignificant, except for regression (4), when we interact it with the market uncertainty. The effect of firm age is U-shaped and significant across all specifications in Table 4, confirming the diminishing return of firm age to innovation.

The effect of perceived risk associated with innovation becomes significant and positive (β = 0.82, p < 0.05) when we control for the interaction between startups and risk as well as startups and uncertainty. The result is intriguing, as it indicates that an increase in perceived risk, to a lesser extent than uncertainty but may have a positive association with innovation. The link risk-innovation is not different between incumbents and startups, which means that both startups and incumbents increase their innovation when the perceived risk is high, while these are only entrepreneurs who increase their innovation under market uncertainty when incumbents do not do it.

A higher level of human capital increases innovation output (β = 0.15–0.31, p < 0.001). Exporters are more likely to learn by exporting and demonstrate on average 8.22–8.49% (specifications 2–4, Table 4) higher level of innovation sales than non-exporters (specifications 1–4, Table 4). A binary variable ‘survival’ picks up firms that survived from 2000 until 2017 is positive but insignificant. This finding demonstrates that innovation is not a ticket for survival, and firms who survive may not be leading innovators or followers. Finally, foreign-owned firms are on average less innovative than domestically owned firms (β = 1.50–1.65, p < 0.01).

Robustness checks

As a robustness check, we estimate equation (1) using OLS estimation with industry and year fixed effects. Our dependent variable ‘innovation sales’ is not treated as censored.

The coefficients in Table 5 present the relationship between the independent variables on firm innovation. Robust standard errors are estimated for these coefficients. Regression (1) includes only control variables as well as knowledge spillover and startup identifier, while regression (2) adds other control variables for knowledge collaboration and absorptive capacity, and regression (3) adds institutional quality measured with the EQI index. Finally, regression (4) tests for the role of uncertainty for firm innovation and the differences between startups and incumbents.

The overall predictive power of the estimated innovation functions increases once we include two- and three-way interactions, with the overall goodness of fit (F-statistics) is between 34.70 and 38.76. Our finding supports H1 on a strong and positive association between market uncertainty and firm innovation with the effect greater for entrepreneurial firms by 1.42% (β = 1.42, p < 0.01). In terms we interpret it as one unit increase in the level of uncertainty (from low to a medium level), is associated with 1.42% on average higher sales from new products (specification 4, Table 5). Interestingly, the coefficient of risk perception is not significant as in the tobit estimation. OLS estimation supports hypothesis 1, which states that entrepreneurs will use market uncertainty to innovate.

The direct effect of knowledge spillover on innovation is positive (β = 4.68, p < 0.01) while on average innovation sales rate is not different between startups and incumbents, with the startup coefficient is not statistically significant (specifications 1–3, Table 5). Once we add a set of controls for absorptive capacity and knowledge collaboration, the coefficient of knowledge spillover drops (β = 0.91, p < 0.01), and the interaction coefficient of startups and knowledge spillover is positive and statistically significant (β = 6.07, p < 0.001). This means that for entrepreneurs, the knowledge spillover has a greater effect on innovation than for incumbent firms. In economic terms, this means that a one-unit increase in the knowledge spillover is associated with an increase in innovation for entrepreneurial firms on average by 6.98% (β = 0.91 + 6.07, p < 0.01), while the knowledge spillover for incumbents remains at 0.91%. Our hypothesis 2 is supported as knowledge spillover for entrepreneurship is greater than for intrapreneurship.

Finally, another limitation of our estimation is the proxy used to measure innovation sales, and in particular the extent of innovativeness of product and services, which can differ between firms and industries. The boundaries between new to market and new to firm products and services may only be defined by filing a patent, however only 2% of the UK firms patent (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Helmers, Rogers and Sena2013) or changing the product code. For example, for the food industry in the USA, the FDA product code needs to be assigned that describes a specific product and contains a combination of five to seven numbers and letters. There is also an industry code that determines the broadest area into which a product falls. We do not have information on the new code assigned to products, but we have information on the firm's R&D investment and seeking patent protection (Arora et al., Reference Arora, Athreye and Huang2016). Our robustness check includes estimating (1) for firms that reported both internal R&D investment and the importance of patent protection for their new products and services. This allows us to crowd out relatively ‘lower quality’ firms that do not invest in R&D and do not consider legal forms of innovation protection and appropriability (e.g. patenting and trademarks). The left firms are perceived as ‘higher quality’ innovators and therefore are more likely to introduce products that are new to market compared to other firms in a sample. Introducing these selection criteria significantly reduces our sample as only 12% of firms in our sample both invest in internal R&D and perceive patent protection as important in protecting innovation in products and services (1,920 observations). Table 6 illustrates a robustness check for our hypotheses using a subsample of R&D-based firms who perceive patent protection as important. A central aspect of the new product to market development is product design and creation which requires investment in R&D as well as legal protection of innovation (Arora et al., Reference Arora, Athreye and Huang2016).

Table 6. Tobit estimation

Dependent variable: Innovation sales % to total sales.

Robust standard errors are in parenthesis. The coefficients of the tobit regressions are the marginal effect of the independent variable on the probability of knowledge spillover, knowledge collaboration, ceteris paribus. For dummy variables, it is the effect of a discrete change from 0 to 1.

Significance level: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Note: Reference category for legal status is Company (limited liability company), industry (mining), region (North East of England).

Source: UKIS – UK Innovation survey; BSD – Business Structure Database.

Specifications 3 and 4 (Table 6) support our main hypotheses 1 and 3, while hypothesis 3 is only partly supported. As we argued above, institutional quality positively moderates the relationship between knowledge spillover and innovation (H3a), while we no longer find support for H3b which states that entrepreneurs benefit more than intrapreneurs by the knowledge spillover and have higher level of innovation activity.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This paper applies Knight's concept of uncertainty to knowledge generated in incumbent organizations to explain the key role played by entrepreneurs to innovate under uncertainty. Unlike incumbent organizations that are discouraged by uncertainty, entrepreneurs embrace uncertainty to commercialize knowledge via innovation activity. Although the extant literature is ambivalent relative efficacy between entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship as a conduit of knowledge spillovers, this study extends Acs and Plummer (Reference Acs and Plummer2005: 442), who state that both incumbent firms and new ventures are able to penetrate the knowledge filter to enable the spillover of new knowledge. We find compelling evidence suggesting that the entrepreneurial firms have a greater return from the knowledge spillover than intrapreneurs as their response to uncertainty is highly shaped by the underlying knowledge in an organizational and environmental context. We theoretically posited and empirically demonstrated that entrepreneurs are a mechanism of the knowledge spillover to innovation activity that requires taking a decision in uncertainty and transforming new knowledge created by an incumbent firm to innovation by founding a new firm.

This study also contributes to the recent research in Hudik and Bylund (Reference Hudik and Bylund2021) about the direction of the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurial decision-making, as their work demonstrated that the latter also affects the former (Hudik and Bylund, Reference Hudik and Bylund2021). The institutional setting causes uncertainty that further burdens entrepreneurs and may force them to exit (Bylund and McCaffrey, Reference Bylund and McCaffrey2017), while institutions can facilitate entrepreneurship in a uni- or bidirectional way. This study bridges the KSTE and the JBA (Foss et al., Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019; Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015) which considers entrepreneurs as a decision-maker, whose judgment constitutes the process of creating, owning, controlling, and combining heterogeneous assets to innovate new products in pursuit of economic profit (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015).

This echoes the works of Knight (Reference Knight1921, Reference Knight1923), who sees the entrepreneur as a decision-maker on how knowledge is used efficiently as well as how to pursue specific goals (Emmett, Reference Emmett1999). Entrepreneurs build on incumbents' knowledge and critical entrepreneurial judgment (Foss et al., Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019) in the face of uncertainty (Knight, Reference Knight1921: 211, 241) which may not be limited to creation of a new firm to commercialize knowledge through innovative activity.

Both entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs can observe and appropriate knowledge spillovers originating from investments in knowledge by incumbent organizations. However, entrepreneurs are more efficient in pursuing a potential (and highly uncertain) innovation than intrapreneurs. Although Knight in his 1921 work identifies why it is only uncertainty that creates a profitable opportunity for entrepreneurs and why entrepreneurial judgment is inherently uncertain, we further contend that managers in incumbent firms and intrapreneurs do employ entrepreneurial judgment as well when assessing potential returns to knowledge investment, but rather that they are more averse to the inherent uncertainty. One could recall multiple examples of patent holders such as large corporations and universities that are ‘shelved’ as managers averse to sell it if the outcome is uncertain. Entrepreneurs have a higher tolerance for the uncertainty that allows them to transform it into new firms and products (Foss, Klein, Kor, Mahoney, Reference Foss, Klein, Kor and Mahoney2008; Knight, Reference Knight1935; Timmons, Reference Timmons1976).

Knight (Reference Knight1921: 310) writes, ‘…risk which leads to a profit is a unique uncertainty resulting from an exercise of ultimate responsibility which in its unique nature cannot be insured nor capitalized nor salaried. Profit arises out of the inherent, absolute unpredictability of things, out of the sheer brute fact that the results of human activity cannot be anticipated and then only in so far as even a probability calculation in regard to them is impossible and meaningless’.

The entrepreneurial judgment is different from that of incumbents (Casson, Reference Casson1982) because entrepreneurs are believed to have an above-average level of willingness to pursue market opportunities, created by the uncertainty of future profits (Kihlstrom and Laffont, Reference Kihlstrom and Laffont1979; Knight, Reference Knight1921), accruing from higher innovation rates and higher returns to knowledge spillovers.

We build on the above argument to extend Kirzner's notion of discovery and uncertainty by examining the role of knowledge spillovers and entrepreneurial judgment (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2015; Klein, Reference Klein2008). Drawing on the KSTE (Acs and Plummer, Reference Acs and Plummer2005), we extend Knight's (Reference Knight1921) and Foss et al. (Reference Foss, Klein and Bjørnskov2019) by modeling how knowledge – associated with uncertainty, transaction costs, and asymmetry and produced by incumbent firms can be used by entrepreneurs to increase the supply of new to market products.

Although Knight (Reference Knight1921) does not provide an algorithm characterizing the decision-making which he calls judgment, he does make it clear that it shaped (Foss and Klein, Reference Foss and Klein2012, Reference Foss and Klein2015) by (1) the ability to act under a high degree of uncertainty and (2) the availability of knowledge from incumbent organizations.

The first major advancement of this study to Knight's (Reference Knight1921) work is in providing the first theoretical synthesis of Knight's (Reference Knight1921) concepts of uncertainty and risk with the KSTE. The second contribution is to identify that the entrepreneurial response to a context where knowledge is highly uncertain is greater than intrapreneurial response within incumbent firms. Together, these insights make it clear that the importance of Knight's (Reference Knight1921) focus on Risk and Uncertainty is as relevant today as ever.

Implications for entrepreneurs and managers

Knight's (Reference Knight1921) book helps us think that innovation results from the knowledge that it is characterized by uncertainty. Our synthesis of two distinct theoretical arguments on how knowledge spills over (Acs et al., Reference Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch and Carlsson2009) and the role of uncertainty and risk for entrepreneurs (Knight, Reference Knight1921) has demonstrated that entrepreneurs benefiting from uncertainty to a greater extent than managers benefit by risk related to the knowledge spillover via innovation activity. We demonstrated that the important sources of knowledge spillover are conferences, fairs, technical and professional associations, patents, and publications, in addition to corporations and universities (Audretsch and Link, Reference Audretsch and Link2019).

Our research findings indicate that startups with access to knowledge spillovers will have a greater propensity to transform knowledge into innovative activity than do incumbents. However, an incumbent firm may also benefit by knowledge spillovers. Our study also suggests that incumbents may not completely control the knowledge created through their own investment due to the knowledge inexcludability (Audretsch and Keilbach, Reference Audretsch and Keilbach2007). They do not reduce their knowledge investments as more knowledge spills over to entrepreneurs. Because knowledge protection can leave protected knowledge under-commercialized, incumbent firms should not and cannot fully appropriate knowledge and thus are vulnerable to knowledge spillovers.

Implications for policy

Innovation policies typically focus on spurring innovation in incumbent firms. However, the results of this study suggest that the uncertainty inherent in new knowledge tends to inhibit innovative activity resulting from intrapreneurship with the firm's organizational boundaries. Rather, entrepreneurship in the form of a new firm startup is a more effective response to knowledge that is uncertain. This suggests that policy might be better advised to focus on policy instruments conducive to entrepreneurship as a conduit for knowledge spillovers rather than prioritizing instruments attempting to spur intrapreneurship within incumbent firms. The rate of return accruing from scarce and expensive policy investments fostering entrepreneurship is likely to exceed that targeting incumbent enterprises.

Limitations and further research

The main limitations of this study are as follows. First, due to the UK Innovation Survey's anonymous nature, no additional sources for information on external partners and sources of knowledge could be added, along with the location of knowledge (regional, national, and overseas). These could have been used to supplement our knowledge with new evidence.

Second, this research focuses specifically on knowledge spillover entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurial response by commercializing knowledge in a context of high uncertainty. Further research would be well advised consider different types of knowledge (e.g. tacit and explicit; basic and applied) (Audretsch and Link, Reference Audretsch and Link2019) and how entrepreneurship scholars following Knight see entrepreneurship as the conduit of knowledge into business profit. Data limitations made it difficult to identify the effort of the entrepreneur to access external knowledge or prior experience of dealing with each specific type of knowledge. Further advancement in the microeconomic foundations requires discussing the role of knowledge spillovers role in the optimal market allocation of resources between knowledge creation and its commercialization.