You got into graduate school! Hooray! Before embarking on a multiyear journey, it’s worth a moment of self-congratulation for this extraordinary achievement. It’s the culmination of everything you have accomplished since, well, kindergarten. It’s also worth recognizing that you did the hard work needed to survey your interests, discover your passions, and determine what field most deserves your talent and energy throughout your professional life. It’s fine if you don’t know what you’ll do with your degree yet – that will come once you have had more experience over the next few years. For now, be excited that you chose psychology – a field that has the potential to understand and improve people’s lives through a focus on literally every thought, feeling, and behavior for literally every minute of every day for every human on the planet. No other discipline can say that, and soon you will be an emerging expert in this most exciting field.

But back to celebration for a moment longer. It is harder to get into graduate school in psychology than most other areas of graduate study, at least in the US. Data are not available for every subdiscipline, but for doctoral programs in clinical psychology, for instance, only 8 percent of applicants get into US programs, and during the pandemic that proportion got a lot smaller as the number of applications nearly doubled. That means that your admission to graduate school may have been harder than getting into med school, law school, or even veterinary school, which means that you have some unusually advanced skills and experience that will most likely be sufficient to ensure you will thrive over the next few years. While admission into these programs is a uniting factor for successful applicants, each student comes in with varying levels of experience, presentations, and publications. You may be tempted to compare yourself to others on these metrics during your first week of classes. Don’t. Each applicant was selected for admission based on their potential to excel in our field, and most of those metrics reflect the generosity of mentors more than students’ potential anyway. Be assured that if you were admitted, you deserve to be in graduate school as much as everyone else. (See Chapter 5 on Imposter Syndrome to help you understand why it’s normal if you sometimes doubt yourself.)

What should you expect during your first year of graduate school and how can you be successful and happy for the next 12 months? That’s what this chapter will touch upon below, with a focus on graduate coursework, some thoughts about your general demeanor and sources of support now that you are on the path to a graduate degree, and some discussion on getting started with research.

1. Graduate Coursework

For many first-year students, graduate coursework may present a confusing paradox. On the one hand, succeeding in courses is kind of in your wheelhouse. It was probably your ability to complete reading assignments, write essays, study for exams, and get good grades that led you to get into a remarkably competitive graduate program. Most programs also contribute to the illusion that coursework is what graduate school is all about; it is common for many first years to take about three courses in each semester of their first year, which leads many people to determine that although this is a lighter courseload than you had as an undergrad, these are graduate courses and thus perhaps more advanced, requiring you to dedicate even more effort on them for your first year. Indeed, these classes can be time-consuming – they will soak up whatever time you allot to them.

Therein lies the paradox, because in actuality, most professors would agree that your coursework actually represents a relatively less important aspect of your graduate training. Of course, it’s not that coursework is unimportant, and you certainly should not ignore your assignments. It’s just not your main focus. That’s for two reasons. First, it is completely expected that you will pass these courses. The graduate school selection process usually is successful in admitting high-achieving, scholastically inclined, and perhaps even perfectionistic (more on this later) students, each of whom has a long history of getting good grades. Assuming you apply a reasonable amount of effort and bring your well-established intellect and thoughtful inquisitiveness into each class, you will do fine. I would not lose sleep over a graduate-level class midterm or final (except perhaps in statistics), because these classes are not expected to yield great variance in students’ performance, and it is widely assumed you will do fine just by being the student you have become in the last 17 years of formal schooling.

But note that there is also a second reason why graduate coursework should not be your main focus: no one will ever see your grades. No internship, postdoctoral fellowship, or eventual job application in academia, practice, or industry will ever ask for your GPA or graduate transcript. (Note: If you apply for a training grant from the National Institutes of Health, they may ask, however.) No one lists a graduate GPA on their CV, and no one will care what grades you got. In fact, some graduate schools don’t even assign formal grades of A, B, C, etc. but rather list Pass vs. High Pass. Now, again – a quick caveat. You should not aim to fail these classes. In fact, most graduate schools will put you on probation if you get a “Low Pass” grade and will expel you for a “Fail.” But under the assumption that this chapter is being read by a student with a long history of academic success, a strong work ethic, and a small dose of perfectionistic tendencies, it is safe to say that you do not need to worry about your grades.

You may be wondering – what is the best orientation to have in graduate coursework, then? It may be worth thinking of your coursework as a context to get exposure to a wide array of theories, findings, approaches, and techniques to expand your thinking in psychology. Probably for that reason, graduate professors are known to offer far more reading assignments each week than any human could possibly complete thoroughly, and each class session is dedicated toward group discussion about these readings to expand your mind and debate the concepts referenced therein. Your understanding of the facts is important, of course, but your ability to engage with the material – question it, apply it, discuss it – is often emphasized more, with graduate training focused on seeing “how you think,” and helping you to become a questioning, informed scholar rather than a regurgitator of facts. It’s good to speak up in graduate school and it’s great to challenge concepts you’ve read about, and point out their limitations. It is NOT great to have your computer opened to surf social media during class, even if you got away with that as an undergrad. Remember, your goal is not to know enough material to get an A; it is to discuss and think about the material in a thoughtful way. Perhaps for those reasons, your assignments will be essays and term papers, and rather than discussing your grades at faculty meetings, your professors will discuss how well you explained and questioned concepts in your written work and during class.

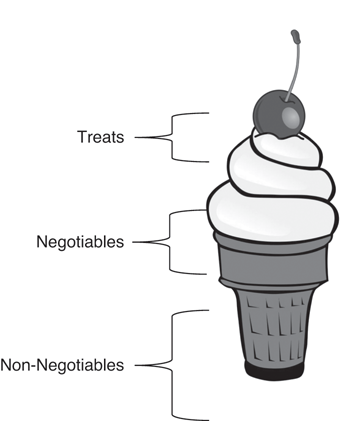

With the exception of your statistics classes in your first year, there is not a lot of studying, per se, in graduate coursework, and truth be told, not all students have completed all readings before all classes (i.e., splitting up readings and trading outlines among classmates is a common practice). But there is a lot of information to digest. In many training programs, graduate training is conceptualized as helping you to progress through three levels, which can be conceptualized as a pyramid perhaps. Those levels are based on the concept that in graduate school your training is meant to help you gain exposure, experience, and expertise. You start at the bottom – the widest level – gaining broad exposure to tons of concepts and ideas (thus, many classes with an abundance of readings). By your second year, you are already taking only two classes a semester (with perhaps zero to one class each semester in your latter years of graduate school), but delving further into your research, teaching, and/or practice where you can apply the information you have been exposed to and gain practical experience. As the pyramid shape implies, you won’t get to experience everything you had exposure to, and there will be some areas of psychology (or some ideas within your area) that were foundational but never lead to applied experiences. That’s ok, and there’s no reason to worry that you are ill-prepared or missing out. Your exposure is supporting your future experiences and will inform your work for decades to come. Similarly, your expertise will represent only a thin sliver of all you were exposed to, or all you experienced. For most students, this expertise comes from your work on your dissertation – the topic of which may be the one area you will feel an expert in when you graduate. This truly is the pinnacle of your graduate school journey and note that it is not based on a class; it is informed by the material you were exposed to in your coursework, and emerged from your experience, but reflects a narrower focus and specific question for which you are one of very few in the world that can claim to be an expert.

In other words, you don’t have to stress out over your coursework as a first-year graduate student, and you are not expected to dedicate excessive energy toward becoming an expert in each class, or on each assignment during your first year. Graduate school is hard enough, and this year should be dedicated toward the enormous adjustment it takes to become a new kind of student. Save some energy to focus on those areas of adjustment below, and trust your well-honed academic skills to be sufficient when it comes to graduate classes.

2. Time Management, Combating Perfectionism, and Getting Support

If you are not hyper-focusing on graduate classes, then what are you doing during your first year of graduate school? Of course, your first year will include a start to your independent (yet, mentored) research career (more on that below), but it may be worth conceptualizing this year as an adjustment year, which includes a focus on skills that are not formally taught, but will be sorely needed for you to succeed in a career in psychology. It has been said that (ok, no it hasn’t, but we are saying it now) that the greatest accomplishment in your first year of graduate school is to develop work habits that will guide you for decades to come.

Graduate school will ask more of you than anyone can achieve. This is not meant to inspire a challenge; this is a fact, and it is one that requires a substantial change in your approach to your graduate career, and perhaps your professional career for years after that. Put simply: you are intentionally being tempted to bite off more than you can chew so you can struggle a bit and learn a new way of chewing. During graduate school, you will learn that you cannot accept every opportunity, you will not do your best on every task, and you will experience critique and rejection. This is a good thing. If you did everything perfectly the day you got there, then you would get the PhD upon admission. You are supposed to fall on your face, get substantial revisions on most of your drafts, and have to redo your work, sometimes from scratch. In graduate school, you should have learning goals, not performance goals. If you strive to be perfect at everything in graduate school, then ironically you have failed in understanding the point of your education. Instead, strive to learn as much as you can in graduate school, and remember that we often learn the most after we stumble.

These challenges will not just come from your formal graduate training. Moving to a new city or state, as is often required, is strenuous on its own. For some, going to graduate school often necessitates leaving behind friends, family, and loved ones. For others, graduate school occurs during the same life stage when we are living truly independently for the first time (i.e., not in a dorm), when we form stable, enduring romantic relationships, or fully realize sexual and gender identities. We are managing a budget to live on (often coming from a small stipend), and beginning to accrue substantial student loan debts. It is the time when we have to keep an apartment, develop a life outside of school that is not created for us by campus life administrators, and develop hobbies that help us find respite. These are the years when parents or grandparents may experience severe illnesses, our siblings may begin to have children, we may be exposed to significant life events, societal stressors, or face new forms of discrimination. It is also a life period when research suggests we may be susceptible to the onset of some types of psychological symptoms. It is a time psychological research refers to as emerging adulthood and all of this is layered on top of a rigorous, demanding, multiyear course of study.

Before we discuss the ways to handle the new work- and lifestyles that graduate school demands, the importance of keeping up with your physical and mental health cannot be overstated. Many graduate students seek psychological treatment to focus on emotional wellness. Your program (or more advanced students) might have recommendations for providers in your area. You will be much better positioned to deal with the demands of graduate school if you make a conscious effort to take care of your body with exercise, regular and healthy meals, and adequate sleep. It sounds simple, but with the potentially consuming nature of your new responsibilities, it’s easier than you might expect to neglect these areas. It will take time to find balance, but you will be better off for it.

You have a lot to adjust to, and one piece of this is the experience of setting your own schedule, determining when and how you best work on graduate school tasks, and developing self-directed initiatives to take on many responsibilities, often without the structure of externally imposed deadlines. It’s important to note that you are the one managing your own work; that is, you likely won’t have a structured list of tasks laid out for you by somebody else. You also are responsible for setting your own agenda and holding yourself to it. That’s a new experience for most people, which means that you are not expected to know how to do it on the first day of graduate school. In a given day during your first month of graduate school, you may have class readings to complete, lab meetings to attend, research ideas you would like to explore, perhaps grading or research responsibilities to finish to earn your stipend, as well as the need to start determining the topic of your master’s thesis, and the daunting notion that there have been about four million articles published in APA’s PsychInfo database, a few hundred of which you will eventually need to read, comprehend, and critique.

That list may make you feel overwhelmed just by reading it, but you can handle it! You may run into trouble, however, if you attempt to do it all at once, if you expect to do it all perfectly, or if you can’t get started. Let’s discuss each of those issues one at a time.

2.1 Time Management

No one takes a course in time management skills. We all kind of test out new ways to impose structure, deadlines, motivators, and reminders into our chaotic lives and we find our flow when we discover which techniques work best for our own workstyle. As a first-year graduate student, you have a system or habit that got you into graduate school … but it may or may not work for you now. Your first year is a time for experimentation, and you should expect that it may take that entire time (or longer) until you have figured out what works for you. Some people use project management software to set deadlines and compile notes they need to keep tasks moving forward. Some have elaborate systems of post-it notes stuck to their computer monitor. Others set daily, weekly, or monthly goals, with reinforcements (hello, frozen yogurt!) for completing tasks along the way. Ask around. Talk with your mentor. Try a system or two to see what works for you. Some graduate students set up writing blocks, and drive to a nearby coffee shop to work so they don’t get distracted. Others prefer to stay up late at night when emails slow down to get some focused time. Some like to plan to draft a paragraph a day and others like to binge-write until an entire paper draft is completed. Just as you are not expected to know how to grade papers, write manuscripts, or run new types of statistical analyses yet, you are not expected to know the best approach to use to accomplish these tasks. It may be a good idea to let your mentor know that you are experimenting so they can support your approach and maybe even offer tips. It will also be a good way to communicate that you are adjusting well to the new demands of graduate school and learning about your workstyle. As your workload increases in later years, you may need to adapt or altogether change your system. But this “meta-understanding” of how you work, and what works for you, is a process that helps you be productive and learn about yourself in a way that will let you understand your strengths, challenges, and when you need to ask for help.

2.2 Combating Perfectionism

As you work through this process of managing your time, you are also collecting data informally on how much time it takes for you to complete tasks. This is a very important piece of your first year of graduate school because it will provide the information you need to help combat perfectionism. As noted above, you simply can’t do all that is asked of you, and you can’t do it all at your best. Reread the prior sentence a few times until it really sinks in, please, because this may be the hardest lesson you learn. You have been positively reinforced for doing your best since the day you were born. But you can’t do your best at every task now that you have reached this level of training. The plain truth is that you’re going to have to half-ass a few things on your list, knowing that your half-ass is probably still an A-level of quality in the grand scheme of things.

Imagine you carve out a day to write an abstract for a poster presentation submission. Could you spend an entire 8 hours working on this task? Sure! Could you spend 3 days on this task? Absolutely. Will there ever be a point when you will look at your draft and say, “This is perfection! Beyond reproach! Every word is gold!” Nope. The fact is that at some point your work has exceeded the bar necessary for the task (i.e., in the case of an abstract for a poster submission, note that over 75 percent are usually accepted at most national conferences) and extra time you spend on it is either unnecessary, or it is suffering from diminishing returns. In other words, you are improving the work less and less with each passing hour.

The same goes for planning a class lecture, grading papers, reading for class, and so on. Some of these are tasks you want to apply your full perfectionistic tendencies toward. But you can’t do so for all of them and one of the best things you can learn during your first year is an understanding of how long it takes you to do a good (maybe even great), but not perfect job on each kind of task. If it takes you about 5 hours to write a poster abstract, schedule 5.5 hours to get it done. Even if you have all day, don’t let yourself obsess over it. Finish and move on. By the end of your first year, you might start learning more about your rhythm and you will have amassed a few cognitive-behavioral “exposure” exercises demonstrating to you that when you turned in your “good” or merely “great” work, the world did not collapse. This may sound easy, but after a lifetime of praise (including at the start of this chapter) for doing excellent work, it may feel quite uncomfortable for some to go to sleep knowing that you did not complete the days’ tasks as completely and perfectly as you are used to. But getting used to that feeling is in some ways what graduate school requires.

Some students feel fine about “good enough” work on lower priority tasks, but get particularly anxious when they must share their work, for fear that it (or they) may be evaluated negatively. This means that perfectionism kicks in when work will be seen by an instructor, a clinical supervisor, or perhaps especially by a mentor. While all teachers, supervisors, and mentors are different, it is probably safe to say that they will be most impressed by growth, rather than perfection right out of the gate. In other words, it is “safe” to show your mentor work that does not represent your best, especially if you communicate where you think improvement is needed, what you are learning and struggling with, and request support as you strive to improve. Mentors prefer to review imperfect work and help students learn new skills than to see students paralyzed or delayed by unnecessary self-imposed expectations. In fact, the discussions about the struggles to make progress or the areas of growth that are needed are often the most rewarding aspects of mentoring for many who chose this as a profession.

An especially productive conversation during one’s first year of graduate school is to talk explicitly about the concepts articulated in this chapter, so you can get candid input from your advisor about their own tips for surviving their first year of graduate school. How did they learn to balance multiple tasks? What do they feel is worth your highest (and next highest, and so on) priority, and what do they feel will offer the most benefit to your education? How long do they spend completing specific tasks, and where do they feel that moderate effort is sufficient to get the job done and turn to higher priority activities? You may learn a lot about your mentor’s workstyle from a conversation like this, and your mentor may appreciate that you are thinking so deeply about the processes required for successful graduate life.

Conversations like these with your mentor will aid one of the most important parts of your first year – you and your mentor getting to know each other and how you work together. This is the start of a years-long, and hopefully lifelong, working relationship. Many first-year students may initially regard their professors as unapproachable experts and often feel funny about calling them by their first name (as is customary in graduate school). Yet unlike an undergraduate professor, your mentor is there to support you through the entire experience of graduate school, which includes not only the struggles with perfectionism and time management discussed above, but also someone to help you find resources and make your life easier when inevitable stressors emerge. Mentors hopefully will not be pushy, or pry into your personal life, of course, but they may share some information about their own lives in an effort to model natural struggles in academia, and to demonstrate coping skills. Talking with other graduate students is a great way to learn about a mentor’s workstyle and mentoring style, and like all relationships, an open channel of communication will allow you to be more efficient, productive, and satisfied with your mentor. This also includes an honest conversation about the boundaries that allow you to feel most comfortable in this relationship.

2.3 Addressing Procrastination

How long was it from the moment you were accepted to graduate school until the moment you first thought: “Holy crap, I have to write a whole dissertation!”? Or did that moment happen just now when reading the preceding sentence? Most students realize the graduate school is a big deal and in addition to the dissertation, there are several important hurdles that each may feel like a big deal (i.e., your master’s, your first presentation in front of the faculty, your qualifying exams, your first patient) – so much so, that it may be hard to get started. This happens to many smart and accomplished people, and it does not reflect weakness or disorganization; it is a sign of respect that you have for the heft of the task before you and your desire to do well. If that pause before working is helpful and allows you to organize your thoughts before working, then all is okay. But if it starts to interfere with the ability to work at all, then it has officially become procrastination.

A note on procrastination and coursework: it can be tempting to use graduate coursework as a way of procrastinating or avoiding one’s own research. This may be a deceptive form of procrastination, as you are still working on something you need to do, but prioritizing coursework before research can be a way of avoiding the more difficult (and, arguably, more important) task of working on one’s own research. Further, students may take comfort in coursework because grades provide semesterly feedback, and validation for students’ efforts, something that may be sparse in other aspects of graduate school. While coursework may feel more manageable, straightforward, or familiar, setting aside protected research time is critical. For instance, some students may find it helpful to dedicate specific days to coursework and others to research, or to set time limits on course assignments.

There should be no “all-nighters” in graduate school, or other last-minute strategies to complete your work, because this is not sustainable for your career. As noted above, this is a time to develop habits that will last you a lifetime. You may have never completed tasks like those assigned to you in graduate school; thus, you won’t necessarily know how much time you need to complete each one. Large tasks can be easily chunked into smaller bits, colloquial drafts can be polished later, and voice memos in your phone can be transcribed later to help you turn what you may find easy to talk about into written prose later, without the experience of a blank screen staring at you judgmentally (note: writing “private drafts” to express what you are really thinking before you start writing the version you will turn in also is a remarkably effective strategy to get started when one is “over-thinking” their work). Procrastination also can be driven by exhaustion or burnout; taking regular breaks is critical. Stepping away from work is important not only for one’s mental health, but also for productivity and for idea generation. Students who have never procrastinated before may find strategies like these helpful when they encounter their first “block” or resistance to working in graduate school. If this happens to you, take it as a good sign. Your strategies in secondary school and in college should not work for you here. This is graduate school and it is not the same type of “school” at all. It should feel different; you should be challenged in new ways; your drafts should have so many track changes from your mentor that the page looks like it is bleeding; and you should feel like you could easily become overwhelmed with opportunities and projects to complete. That’s how we grow in graduate school.

3. Getting Support

Graduate school is not quite like medical or law school, and is very different from a full-time job that one may get in the business world, or at a local commercial establishment. It may be hard to find support because it often takes so long to explain to people what exactly your life is like now. Your fellow graduate student peers may be an outstanding resource for you as you begin.

Graduate school represents a period of unprecedented change and growth for many of us, and having others to commiserate and empathize may be a social necessity. If you have entered your program with other first-year students, this cohort represents a group of individuals who will most likely have similar interests, ambitions, and prior experiences. As discussed earlier, first-year graduate students are thrust into a brand new social environment, often without the comfort of their close friends nearby. Luckily, most others in your class also likely have recently vacant social lives, providing a mutually beneficial opportunity for friendship. These individuals can uniquely relate to the trials and tribulations that may arise during the first year of graduate school. Additionally, growing close with your fellow graduate students may confer unique academic opportunities. Having a small group of individuals to share ideas related to coursework or research is enormously beneficial. Fellow first years also can provide expertise in their specific niches, and thus are valuable resources for fresh perspectives and collaboration across a variety of diverse topics. Indeed, brainstorming creative ways to intertwine your own research interests with those of your peers can lead to exciting projects which may intersect multiple subfields of psychology. But of course, beware – these interactions with your peers are also fertile ground for social comparisons, particularly if your friend asks you if you’re planning on applying for some fancy grant you’ve never heard of, or mentions they are pulling together a symposium for a conference while you’re working on your first poster. Try to turn these moments of intimidation or insecurity into inspiration. Everyone learns and reaches milestones at different rates and it will be all the more sweet when you can motivate and celebrate each other. Anecdotally, it is more common than not that the student you were in awe of as a first year will tell you years later that it was you that seemed intimidating to them.

4. Starting Your Research

You talked about research in your graduate school applications, you discussed it in your interviews, you have tried to explain it to your family and friends a zillion times (“No, it is not just searching for things on Google”) and now you are here, and everyone says you are supposed to get started doing research.

Umm … do what, exactly? How do I start doing this, and why does everyone talk to me like I understand what ‘research’ is already?

If you are a first-year student who has had this thought, know that you are not alone. Many first-year students have had experience assisting graduate students or faculty with their own work, but many have never been an “independent” or principal investigator on their own. So you may feel ready to “run subjects,” supervise undergrads, or search PsychInfo, but you may not feel like you are clear on the steps needed to start your own research program. This makes the first year of graduate school potentially challenging and anxiety-provoking.

Let’s start at the very beginning. As a first-year student, “doing research” could mean a million (well, ok, actually about a dozen) different things, including reading articles on topics that interest you, learning about available data sets in your advisor’s lab, reading the study protocol from recent studies done by your peers and advisors, reading the human subjects or grant applications that support your lab’s work, watching videos of prior subject “runs,” running some simple descriptive statistics (e.g., means, correlations) on available data sets, watching conference presentations online, or just sitting around and thinking of hypotheses that could be interesting to test. As a first-year graduate student, all of this “counts” as research, and it is probably useful to establish a foundation of knowledge about prior work in the field, extant resources, and a self-assessment of what excited you the most. Particularly essential – ask tons of questions of your peers and mentor about their recent research: what did they study, why, how did they think about prior work in the field, how is their work unique, where do they think the field is going, what were their initial ideas and what pitfalls did they experience, what have they recently discussed in the lab, what other investigators do they follow, and so on, and so on. You find yourself now in an exceptionally rich intellectual environment, surrounded by faculty and students. Use the people around you as resources. In addition to learning from their answers to these questions, you can and should explore collaboration possibilities, ask for help, ask them if they have access to the software you need, bounce ideas off each other, share skills, or just enjoy their friendship and social support. If the first year of graduate school is meant to develop your ability to “think” like a researcher, then these conversations will be enormously helpful to achieve that goal. Don’t worry about bothering people, because enjoying these types of discussions is likely a large part of why they are in academia to begin with.

Based on your lab, and how data are collected, analyzed, and prepared for presentation/publication, you may have an opportunity (or requirement) to begin coming up with your own research questions. See the sections above in this chapter about the best way to get started with this task, without becoming plagued by time management challenges, paralyzing perfectionism, or procrastination. It is helpful to develop a system for keeping track of ideas, whether in a notebook, spreadsheet, or other format. You may also consider saving relevant research articles or identifying and following researchers whose publications interest you. In fact, if you feel comfortable thinking of research ideas early in your first year, or by the beginning of your second year, you may want to even consider applying for a graduate fellowship. This is briefly discussed below. Lastly, the research idea phase can seem daunting, undefined, and limitless; it may be that starting a project (e.g., a fellowship application, publication) even before you have finalized your research focus is necessary in order to move forward. Often research ideas are developed in the writing process, and beginning a project can help when the brainstorming phase begins to feel stagnant.

Once you begin writing, you may notice an interesting quandary: most scientific writing in our field has an authoritative and didactic tone, often using statements that seem to capture an entire field or trend with decades of knowledge behind it (e.g., “For a scientific discipline focusing on the study of behavior, it is ironic that so few investigators have examined the behaviors that best predict scientific productivity”). Yet, first-year students almost never have the experience to encapsulate an entire body of literature with statements such as these, making it hard to write in the manner that academic scholarship may require.

This is one reason why it is so common for even fantastic writers to go through many, many drafts when they begin writing scientific presentations and publications in graduate school. Each draft leads the writer back to the literature to learn more, which helps inform both changes in the content and writing style of the next draft, and so on. Nevertheless, first-year students can rely on two tips to help them accelerate the development of their scientific writing acumen. First, a terrific and recent review paper (especially in a high-impact journal) is worth its weight in gold. If done correctly, a paper that has well summarized the extant literature and listed areas of repetition vs. gaps has given you most of what you need to begin writing in an authoritative voice. Beware of the literature review that is not very high in quality, or in a highly respected outlet. Of course, you also need to do exhaustive searches of the literature yourself. But a great literature review can help you feel more confident that your conclusions are supported by other experts who may have been in the field for longer than you, and you can probably find many terrific papers to read by searching for the papers in this literature review first.

A second tip will send you back to your mentor’s office, and that’s a good thing. Mentors often have thought deeply about the field and the topic you are writing about, so it is great to simply interview them for their perceptions of the “current state of the literature.” Assuming that your mentor will likely be an author on whatever you are writing in your first year, it is acceptable to include their own perspective in your writing, and even to use their words in your writing (i.e., after all, they are an author too). Some labs may offer you an informal chance to hear your mentor’s perspective on the literature as you discuss recent, relevant papers. If not, then asking your mentor to talk about their opinions, their impressions of other scholars’ work, and why they think your research will make an important contribution is a great way to get started. Mentors think of this as a “scaffolding” approach, to borrow a term from the parenting literature in developmental science. The mentor will give you as much structure as you need to help you stand on your own, and will slowly remove that structure or tangible support to keep you working just beyond your current skill level. Data suggest that is the way that you will keep growing, but never feel like you will fall flat on your face. Let’s acknowledge, however, that this approach has two potentially negative consequences: (1) you may rarely feel fully competent while in graduate school; and (2) you may feel frustrated that your mentor is constantly raising the bar of expectations as the years progress. If this seems true for you, it is always ok to ask your mentor if you are progressing well “based on your current level of training,” to help you gain your footing and know that although you are still growing, you are on track.

4.1 NSF Graduate Research Fellowship

The National Science Foundation (NSF) offers research fellowships to hundreds of young scholars, including those involved in the study of psychological science. These fellowships require only a few pages of essays (i.e., one is similar to a personal statement, the other is a research proposal). Applicants can apply either (a) before attending graduate school; and/or (b) in the first or second years of graduate school. Applicants may apply once per eligibility window; in other words, a student may apply before graduate school and, if unsuccessful, may apply once more in the first two years of graduate school. Applicants who receive an honorable mention are not eligible to reapply, and additional eligibility criteria exclude students with a master’s or other professional degree (see the NSF GRFP website for more information on eligibility).

NSF applicants are evaluated differently based on how many years of experience they have at the time of applying. Applications are reviewed by 2–3 scholars with relevant areas of experience broadly (i.e., within all of developmental or cognitive psychology, for instance). An honorable mention is a prestigious honor that can be proudly listed on one’s CV. Fellowship winners get three years of funding (that need not be consecutive) with a stipend significantly higher than most graduate assistantships and access to other potential resources of ancillary experiences afforded to fellowship winners. More information is available at www.nsfgrfp.org/.

Many students in psychology apply for the NSF graduate research fellowship, and it is quite competitive. So is the NIH National Research Service Award (F31 grant) that is available to graduate students when they are planning dissertation-level research. Because the preparation of the application for the NSF has become very common among students in research-oriented doctoral programs, a few tips are offered here.

First, as noted above, applicants are evaluated based on their level of training, and those with above average accomplishments are naturally likely to stand out from their peers. Often, this is evaluated by the number of presentations at national conferences or publications in high-impact peer-reviewed journals. Applicants applying as an undergraduate or post-baccalaureate typically have zero publications; thus, authorship on two may gain favorable notice. This would seem less unusual for a research-oriented student applying at the start of their second year. Applicants with impressive academic pedigrees (i.e., from top-ranked undergraduate institutions, those with very high GPAs) tend to receive more favorable scores in the NSF grant review process (a database of all recipients is available on the NSF website), although an emphasis on diversity and first-generation students in recent years may have helped reviewers move toward more inclusive academic indicators that more equitably reflect achievement across all promising young scholars.

Perhaps most important is that applicants show a lifelong commitment to science, and a strong capacity to develop rigorous and unique scientific questions. The two required essays for the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, a personal statement and a research proposal statement, offer opportunities for applicants to demonstrate each.

Using one’s personal statement from graduate school admission for the NSF application is not always advisable, whereas using one’s NSF personal statement in a graduate school application can work well. That’s because unlike the typical graduate school statement that begins discussing undergraduate coursework and research experiences and a specific set of refined research questions to match a specific research lab, the successful NSF personal statement essay is far grander. The narrative often starts earlier, with a discussion of a love for science that may have begun very early, a discussion of extracurricular and volunteer activities that demonstrate a penchant for science, and/or a drive to change a major societal issue or injustice through investigation and dissemination of psychological science. NSF reviewers may prefer an applicant who thinks big and has been unusually committed to a cause or an opportunity for change since relatively early in life. Successful applicants weren’t only president of their local Psi Chi chapter, or recognized a variable missing from prior work on a topic; they are more likely to have developed a new student association in high school to address societal issues (e.g., world hunger, disparate access to education, discrimination, etc.), founded or led efforts for a charity, or worked across disciplines to develop innovative new directions for science. Don’t worry – a Nobel prize is not a requirement for the NSF fellowship, but a more typical essay about loving psychology after Psych 101 class, or participating in a lab before you graduated, may not always cut it. While the personal essay should primarily tell a personal narrative, it is wise to draw connections between your prior experiences and the specific research interests or aims articulated in your research proposal essay. For example, if your proposal focuses on mechanisms of emotion regulation, a strong personal statement would include discussion of prior experiences through which an interest in emotion, emotion regulation, or related constructs developed.

NSF reviewers also would like to see the potential for rigorous and innovative scientific questions within the research proposal statement, the second essay of the application. This is a peculiar essay to write because the successful applicant is not necessarily expected to actually conduct the research proposed in the application (i.e., funds are not provided to conduct a large-scale study, and as many applicants don’t know where they will go to graduate school, it is unknown whether subject populations or necessary resources will be available to conduct the proposed research). Yet the application requests a specific research proposal that might represent the best possible study (not a fantasy study, but an actual, potentially feasible one) that could be done assuming reasonable research resources. Further, the research proposal should avoid an explicitly clinical focus. This is a particular challenge for clinical psychology graduate students, whose research interests, prior research experiences, and graduate coursework largely center around psychopathology and related topics in clinical psychology. However, an NSF application should adopt a more “basic science” approach and avoid focusing on clinical outcomes. This does not mean you need to write a research proposal statement that deviates radically from your research interests; instead, the NSF application may require recasting your interests into a different, though related, research question. It may be helpful to think of constructs that are relevant to clinical psychology (e.g., emotion, development) but that do not necessarily involve psychopathological outcomes. Keep in mind that you will need to select a subdiscipline within psychology under which to submit your research proposal statement (e.g., social, cognitive, developmental, affective, etc.), and that this category can help guide the angle you take in your research proposal.

NSF reviewers have plenty of experience reviewing grants, so you can expect lots of specific comments on small details in the proposed research that could substantially lower one’s score. Most students work on these essays with their mentors, naturally. Mentors don’t write the application, of course, but the process of discussing the proposed research is a learning experience in itself, with applicants finding the balance between their interests and real-world limitations. As with all applications for funding, it is always best to read as many successful and unsuccessful applications as possible when beginning, and to have as many readers of drafts as possible before submitting. The deadline for the NSF fellowship is typically in late October, so this can make for an active jump start to graduate school for those who apply in their first year.

5. Summary

Getting into graduate school is a huge achievement, and the start to an educational pathway that is quite different from the many years of schooling preceding matriculation. You are not expected to know what you are doing when you arrive, and your first year is likely best spent adjusting to a new university, with new colleagues, peers, mentors, and expectations. The first year of graduate school is a great time to establish habits that you can benefit from for decades to come, including the recognition that our field will ask more of you than any human could ever deliver. So it’s essential that you learn how to pace yourself, set expectations that are reasonable, and find ways to be kind to yourself. You will never be less busy from this point forward, but in this year, you can learn to be someone who will keep work stimulating, find ways to be productive, yet also recognize that life is more than your career in psychology.

If the average applied psychology student is asked confidentially why they are pursuing a career in their field, the most likely answer is “to help people.” Although this answer is such a cliché that it sometimes causes graduate admissions committee members to wrinkle their noses, in fact it is perfectly appropriate. The ultimate purpose of applied psychology is to alleviate human suffering and promote human health and happiness. Unfortunately, good will does not necessarily imply good outcomes. If mere intentionality were enough, there would never have been a reason for psychology in the first place, because human beings have always desired a happy life and shown compassion for others. It is not enough for psychology students to want to help: one must also know how to help.

In most areas of human skill and competence, “know-how” comes in two forms, and psychology is no exception. Sometimes knowledge is acquired by actually doing a task, perhaps with guidance and shaping from others, and with a great deal of trial and error. This approach is especially helpful when the outcomes of action are immediate, clear, and limited to a specific range of events. Motor skills such as walking or shooting a basketball are actions of that kind. The baby trying to learn to walk stands and then falls hundreds of times before the skill of walking is acquired. The basketball goes through the hoop or it does not, providing just the feedback needed – even experienced players will shoot hundreds of times a day to keep this skill sharp. In areas such as these, “practice makes perfect,” or at least adequate.

Sometimes, however, knowledge is best acquired in part through verbal rules. This approach is especially helpful when a task is complex and the outcomes are probabilistic, delayed, subtle, and multifaceted. You could never learn to send a rocket to the moon or to build a skyscraper through direct experience. For rule-based learning to be effective, however, the rules themselves have to be carefully tested and systematized. One of the greatest inventions of human beings the last 2000 years has been the development of the scientific method as a means of generating and testing rules that work. Human “know-how” has advanced most quickly in areas that are most directly touched by science, as a glance around almost any modern living room will confirm.

The problem faced by students of applied psychology is that the desire to be of help immediately pushes in the direction of “learning by doing” even though often the situations applied psychologists face do not produce outcomes that are immediate, clear, or occur within a known range of options. Consider parents who want to know how to raise their children. There are times that poor advice can seem to produce good immediate outcomes at the expense of long-term success. For example, telling children they are doing wonderfully, no matter what, may feel good initially but the children may grow up with a sense of entitlement and a poor understanding of how hard work is needed to succeed. Similarly, a clinician in psychotherapy can do an infinite number of things. The immediate results are a weak guide to the acquisition of real clinical know-how because effects can be delayed, probabilistic, subtle, and multifaceted.

All of this would be admitted by everyone were it not for two things. First, some aspects of the clinical situation are and need to be responsive to directed shaping and trial and error learning. Experience alone may teach clinicians how to behave in the role of a helper, for example. As the role is acquired, the confidence of clinicians will almost always increase, because the clinician “knows what to do.” Some of this kind of learning is truly important, such as learning to relate to another person in a genuine way, but trial and error does not necessarily lead to an increase in the ability to actually produce desired clinical outcomes. That brings us to the second feature of the situation that can mistakenly capture the actions of students in professional psychology. Clients change for many reasons and what practitioners cannot see, without specific attempts to do so, is what would have happened if the practitioner had done something different. Many medical practices (e.g., blood-letting; mud packs) survived for centuries due to the judgmental bias produced by this process. Many problems wax and wane regardless of intervention, and some features of professional interventions are reassuring and helpful almost regardless of the specifics. Thus, with experience, most practitioners feel not only confident, but also competent, because in general it appears that good outcomes are being achieved. It is natural in these circumstances for the practitioner to respond based on their “clinical experience.”

That is a mistake. Over more than half a century in virtually every area in which clinical judgment is pitted against statistical prediction, statistical prediction does a better job (Reference Grove and LloydGrove & Lloyd, 2006). Yet even when faced with clear clinical failures, practitioners are most likely to rely on clinical judgment rather than objective data to determine what to do next (Reference Stewart and ChamblessStewart & Chambless, 2008). This suggests that it can be psychologically difficult to integrate the rules that emerge from research with one actual history of ongoing effort to be of help to others.

Part of the problem is that science can suggest courses of action that are not personally preferred, which takes considerable psychological flexibility to overcome. Consider the use of exposure methods in anxiety disorders, which arguably have stronger scientific support than any other form of psychological intervention for any mental health problem (Reference Abramowitz, Deacon and WhitesideAbramowitz et al., 2019). Despite overwhelming empirical support, few clients receive this treatment, and when they do, often it is not delivered properly (Reference Farrell, Deacon, Kemp, Dixon and SyFarrell et al., 2013). Dissemination research has helped explain this distressing fact. Meta-analyses show that training in exposure increases knowledge about it, but not its use (Reference Trivasse, Webb and WallerTrivasse et al., 2020). Instead, what most determines use of exposure is the psychological posture of clinicians themselves. When practitioners are unwilling to feel their own discomfort over causing discomfort in someone else, even if it will help them, they avoid using exposure methods or detune their delivery (Reference Scherr, Herbert and FormanScherr et al., 2015). Problems of this kind abound in evidence-based care. As another example, drug and alcohol counselors need to learn to sit with their discomfort over “using drugs to treat the use of drugs” to encourage the use of methadone for clients addicted to heroin (Reference Varra, Hayes, Roget and FisherVarra et al., 2008). Rules alone do not ensure use of evidence-based practices: practitioners themselves need to be open to the psychological difficulties of that scientific journey and scientists need to think of practitioners more as people than as mere tools for dissemination (Reference Hayes and HofmannHayes & Hofmann, 2018a).

In one sense, scientist-practitioners are those who have deliberately stepped into the ambiguity that lies between the two kinds of “know-how.” They are willing to live with the conflict between the urgency of helping others and the sometimes slow pace of scientific knowledge. Fortunately, due to the past efforts of others, in most areas of applied psychology this is a road that fits with provider values: this openness to discomfort is for a larger purpose. There is considerable evidence that the use of empirically supported procedures increases positive outcomes (Reference Hayes and HofmannHayes & Hofmann, 2018b). When agencies convert to the use of such methods, client outcomes are better, especially if practitioners are encouraged to fit specific methods to specific client needs (Reference Weisz, Chorpita, Palinkas, Schoenwald, Miranda, Bearman, Daleiden, Ugueto, Ho, Martin, Gray, Alleyne, Langer, Southam-Gerow and GibbonsWeisz et al., 2012). Improvements tend to be longer-lasting (Reference Cukrowicz, Timmons, Sawyer, Caron, Gummelt and JoinerCukrowicz et al., 2011), and staff turnover is reduced (Reference Aarons, Sommerfeld, Hecht, Silovsky and ChaffinAarons et al., 2009).

But in other ways, this is a road with difficulties. Most patients given psychosocial treatment do not receive evidence-based care (Reference Wolitzky-Taylor, Zimmermann, Arch, De Guzman and LagomasinoWolitzky-Taylor et al., 2015). There are some understandable reasons. Adherence to treatment manuals does not alone guarantee good outcomes (Reference Shadish, Matt, Navarro and PhillipsShadish et al., 2000) and the important work of learning how to use scientifically supported methods in more flexible ways to fit individual needs is still in its infancy (Reference Fisher and BoswellFisher & Boswell, 2016; Reference Hayes, Hofmann and StantonHayes, Hofmann, & Stanton, 2020). It is important to know the specific processes of change that account for the effects of these methods, but that is often not clear (Reference Hayes, Hofmann and CiarrochiHayes, Hofmann, & Ciarrochi, 2020; Reference La Greca, Silverman and LochmanLa Greca et al., 2009). While there is considerable evidence that relationship factors are key to many clinical outcomes (Reference Norcross and WampoldNorcross & Wampold, 2011), there remains limited evidence of the specific variables that alter these factors while maintaining positive outcomes (Reference Creed and KendallCreed & Kendall, 2005; Reference Hayes, Hofmann and CiarrochiHayes, Hofmann, & Ciarrochi, 2020).

What often drives the research of an applied scientist is the possibility of doing a greater amount of good by reaching a larger number of people than could be reached directly. Ultimately the idea that scientifically filtered processes and procedures will help more people more efficiently and effectively is the dream of applied science. Unfortunately, this dream is surprisingly hard to realize. It is difficult to produce research that will be consumed by others and that will make a difference in applied work. For the practitioner, a reliance on scientifically based procedures will not fully remove the tension between clinical experience and scientific forms of knowing, because virtually no technologies exist that are fully curative, and only a fraction of clients will respond fully and adequately based on what is now known.

This chapter is for students who are considering taking “the scientific path” in their applied careers. We will discuss how to be effective within the scientist-practitioner model, whether in the clinic or in the research laboratory. We will briefly examine its history, and then consider how to produce and consume research in a way that makes a difference.

1. History of the Scientist-Practitioner Model

From the early inceptions of applied psychology, science and practice were thought of by many as inseparable. This is exemplified by Lightmer Witmer’s claim that:

The pure and the applied sciences advance in a single front. What retards the progress of one, retards the progress of the other; what fosters one, fosters the other. But in the final analysis the progress of psychology, as of every other science, will be determined by the value and amount of its contributions to the advancement of the human race.

This vision began to be formalized in 1947 (Reference Shakow, Hilgard, Kelly, Luckey, Sanford and ShafferShakow et al., 1947) when the American Psychological Association adopted as standard policy the idea that professional psychology graduate students would be trained both as scientists and as practitioners. In August of 1948 a collection of professionals representing the spectrum of behavioral health care providers met in Boulder, Colorado with the intent of defining the content of graduate training in clinical psychology. One important outcome of this two-week long conference was the unanimous recommendation for the adoption of the scientist-practitioner model of training. At the onset of the conference, not all attendees were in agreement on this issue. Some doubted that a true realization of this model was even possible. Nevertheless, there were at least five general reasons for the unanimous decision.

The first reason was the understanding that specialization in one area versus the other tended to produce a narrowness of thinking, thus necessitating the need for training programs that promoted flexibility in thinking and action. It was believed that such flexibility could be established when “persons within the same general field specialize in different aspects, as inevitably happens, cross-fertilization and breadth of approach are likely to characterize such a profession” (Reference RaimyRaimy, 1950, p. 81).

The second reason for the unanimous decision was the belief that training in both practice and research could begin to circumvent the lack of useful scientific information regarding effective practice that was then available. It was hoped that research conducted by those interested in practice would yield information useful in the guidance of applied decisions.

The third reason for the adoption of the scientist-practitioner model was the generally held belief that there would be no problem finding students capable of fulfilling the prescribed training. The final two reasons why the model was ultimately adopted is the cooperative potential for the merger of these two roles. It was believed that a scientist who held at hand many clinical questions would be able to set forth a research agenda adequate for answering these questions, and could expect economic support for research agendas that could be funded by clinical endeavors.

Despite the vision from the Boulder Conference, its earnest implementation was still very much in question. The sentiment was exemplified by Reference RaimyRaimy (1950):

Too often, however, clinical psychologists have been trained in rigorous thinking about nonclinical subject matter and clinical problems have been dismissed as lacking in “scientific respectability.” As a result, many clinicians have been unable to bridge the gap between their formal training and scientific thinking on the one hand, and the demands of practice on the other. As time passes and their skills become more satisfying to themselves and to others, the task of thinking systematically and impartially becomes more difficult.

The scientist-practitioner model was revisited in conference form quite frequently in the years that followed. While these conferences tended to reaffirm the belief in the strength of the model, they also revealed an undercurrent of dissatisfaction and disillusionment with the model as it was applied in practice. The scientist-practitioner split feared by the original participants in the Boulder Conference gradually became more and more of a reality. In 1961, a report published by the Joint Commission on Mental Health voiced concerns regarding this split. In 1965 a conference was held in Chicago where the participants displayed open disgruntlement about the process of adopting and applying the model (Reference Hoch, Ross and WinderHoch et al., 1966).

The late 1960s and 1970s brought a profound change in the degree of support for the scientist-practitioner model. Professional schools were created, at first within the university setting and then in free-standing form (Reference PetersonPeterson, 1968, Reference Peterson1976). The Vail Conference went far beyond previous conferences in explicitly endorsing the creation of doctor of psychology degrees and downplaying the scientist-practitioner model as the appropriate model for professional training in psychology (Reference KormanKorman, 1976). The federal government, however, began to fund well-controlled and large-scale psychosocial research studies, providing a growing impetus for the creation of a research base relevant to practice.

The 1980s and 1990s saw contradictory trends. The split of the American Psychological Society (now the Association for Psychological Science) from the American Psychological Association, a process largely led by scientist-practitioners, reflected the growing discontent of scientist-practitioners in professional psychology disconnected from science (Reference HayesHayes, 1987). Professional schools, few of which adopted a scientist-practitioner model, proliferated but began to run into economic problems as the managed care revolution undermined the dominance of psychology as a form of independent practice (Reference Hayes, Follette, Dawes and GradyHayes et al., 1995). The federal government began to actively promote evidence-based practice, through a wide variety of funded initiatives in dissemination, diffusion, and research/practice collaboration. Research-based clinical practice guidelines began to appear (Reference Hayes and GreggHayes & Gregg, 2001), and the field of psychology began to launch formal efforts to summarize a maturing clinical research literature, such as the Division 12 initiative in developing a list of empirically supported treatments (Reference Chambless, Sanderson, Shoham, Johnson, Pope, Crits-Christoph, Baker, Johnson, Woody, Sue, Beutler, Williams and McMurryChambless et al., 1996). An outgrowth of APS, the Academy of Psychological Clinical Science (APCS), began with a 1994 conference on ‘‘Psychological Science in the 21st Century.’’ In 1995, the APCS was formally established and began recognizing doctoral and internship programs that advocated science-based clinical training.

In the 2000s, the movement toward “evidence-based practice” began to take hold in psychology (Reference GoodheartGoodheart, 2011), but the definition of “evidence” was considerably broadened to give equal weight to the personal experiences of the clinician and to scientific evidence. The penetration of formal scientific evidence into psychological practice continued to be slow (Reference Stewart and ChamblessStewart & Chambless, 2007), which began to receive national publicity. For example, Newsweek ran a story under the title “Ignoring the Evidence: Why do psychologists reject science?” (Reference BegleyBegley, 2009). Practical concerns also began to be raised about the dominance of the individual psychotherapy model in comparison to web- and phone-based interventions, self-help approaches, and media-based methods (Reference Kazdin and BlaséKazdin & Blasé, 2011). Treatment guidelines (e.g., Reference Hayes, Follette, Dawes and GradyHayes et al., 1995) began to be embraced even by leaders of mainstream psychology (Reference GoodheartGoodheart, 2011). Finally, more science-based organizations took stronger steps to accredit training programs that emphasize a “clinical scientist” model, and to advocate for these values in the public arena. In 2007 the APCS formally launched the Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System; in 2011 there were about a dozen doctoral programs accredited by this process; a decade later there are over 60 accredited programs and 12 internships.

The last decade has been what looks like a retrenchment in many ways, but really it is more of a revitalization and reformation of the scientist-practitioner model. A substantial body of evidence about what practices work best is now available, but the systems for disseminating that evidence are faltering. For example, the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices maintained by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in the United States Department of Health and Human Services (www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/) has been shut down by the United States government, and the list of evidence-based intervention methods maintained by the Clinical Psychology Division of the American Psychological Association is being updated only irregularly. At the same time, professional training programs that eschew the importance of science to day-to-day professional practice continue to grow.

With the publication of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, the funders of research in mental illness appear to have abandoned hope that research focused on syndromes will ever lead to a deep understanding of mental health problems. In part in response to criticisms of the DSM-5, the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH) established the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) program that aims to classify mental disorders based on processes of change linked to developmental neurobiological changes (Reference Insel, Cuthbert, Garvey, Heinssen, Pine, Quinn, Quinn, Sanislow and WangInsel et al., 2010).

Meanwhile, psychology is turning in a more process-based direction as well (Reference Hayes and HofmannHayes & Hofmann, 2018b), with a greater emphasis on theory-based, dynamic, progressive, contextually bound, modifiable, and multilevel changes or mechanisms that occur in predictable, empirically established sequences oriented toward desirable outcomes (Reference Hofmann and HayesHofmann & Hayes, 2019). If this transition continues, trademarked protocols linked to syndromes will receive less attention in the future as a model of evidence-based therapy, and comprehensive models of evidence-based processes of change, linked to evidence-based intervention kernels that move these processes, and that help a specific client achieve their desired goals, will receive more attention.

The student of applied psychology needs to think through these issues and consider their implications for professional values. Professionals of tomorrow will face considerable pressures to adopt evidence-based practices. We would argue that this can be a good thing, if psychological professionals embrace their role in the future world of scientifically based professional psychology. Doing so requires learning how to do research that will inform practice, how to assimilate the research evidence as it emerges, and how to incorporate empiricism into practice itself. It is to those topics that we now turn.

2. Doing Research That Makes a Difference

The vast majority of psychological research makes little impact. The modal number of citations for published psychological research between 2005 and 2010 was only two (Reference KurillaKurilla, 2017) and most psychology faculty and researchers are little known outside of their immediate circle of students and colleagues. From this situation we can conclude the following: If a psychology student does what usually comes to mind in psychological research based on the typical research models, he or she will make only a limited impact, because that is precisely what others have done who have come to that end. A more unusual approach is needed to do research that makes a difference.

Making a difference in psychological research can be facilitated by clarity about (a) the nature of science, and (b) the information needs of practitioners.

2.1 The Nature of Science

Science is a rule-generating enterprise that has as its goal the development of increasingly organized statements of relations among events that allow analytic goals to be met with precision, scope, and depth, and based on verifiable experience. There are two key aspects to this definition. First, the product of science is verbal rules based on experiences that can be shared with others. Agreements about scientific method within particular research paradigms tell us how and when certain things can be said: for example, conclusions can be reached when adequate controls are in place, or when adequate statistical analyses have been done. A great deal of emphasis is placed on these issues in psychology education (e.g., issues of “internal validity” and “scientific method”) and we have little additional to offer in this chapter on those topics.

Second, these rules have five specific properties of importance: organization, analytic utility, precision, scope, and depth. Scientific products can be useful even when they are not organized (e.g., when a specific fact is discovered that is of considerable importance), but the ultimate goal is to organize these verbal products over time. That is why theories and models are so central to mature sciences.

The verbal products of science are meant to be useful in accomplishing analytic ends. These ends vary from domain to domain and from paradigm to paradigm. In applied psychology, however, the most important analytic ends are implied by the practical goal of the field itself – namely, the prediction and influence of psychological events of practical importance. Not all research practices are equal in producing particular analytic ends. For example, understanding or prediction are of little utility in actually influencing target phenomena if the important components of the theory cannot be manipulated directly. For that reason, it helps to start with the end goal and work backward to the scientific practices that could reach that goal. We will do so shortly by considering the research needs of practitioners.

Finally, we want theories that apply in highly specified ways to given phenomena (i.e., they are precise); apply to a broad range of phenomena (i.e., they have scope); and are coherent across different levels of analysis in science, such as across biology and psychology (i.e., they have depth). Of these, the easiest to achieve is precision, and perhaps for this reason the most emphasis in the early days of clinical science was on the development of manuals and technical descriptions that are precise and replicable. Perhaps the hardest dimension to achieve, however, is scope, and, as we will argue in a moment, that is the property most missing in our current approaches to applied psychology.

2.2 The Knowledge Needed by Practitioners

Over 50 years ago, Gordon Paul eloquently summarized the empirical question that arises for the practitioner: “what treatment, by whom, is most effective for this individual with that specific problem, and under which set of circumstances does that come about” (Reference Paul and FranksPaul, 1969). Clients have unique needs, and unique problems. For that reason, practitioners need scientific knowledge that tells them what to do to be effective with the specific people with whom they work. It must explain how to change things that are accessible to the practitioner so that better outcomes are obtained. Practitioners also need scientifically established know-how that is broadly applicable to the practical situation and can be learned and flexibly applied with a reasonable amount of effort and in a fashion that is respectful of their professional role.

Clinical manuals have been a major step forward in developing scientific knowledge that can focus on things the clinician can manipulate directly in the practical situation, but not enough work has gone into how to develop manuals that are easy to master and capable of being flexibly applied to clients with unique combinations of needs (Reference Kendall and BeidasKendall & Beidas, 2007). With the proliferation of empirically supported manuals, more needs to be done to come up with processes that can allow the field to synthesize and distill down the essence of disparate technologies, and combine essential features of various technologies into coherent treatment plans for individuals with mixed needs.

That is a major reason that a focus on processes of change has grown. In essence, Paul’s question is being reformulated to this one: “What core biopsychosocial processes should be targeted with this client given this goal in this situation, and how can they most efficiently and effectively be changed?” (Reference Hofmann and HayesHofmann & Hayes, 2019, p. 38.)

The only way that question can be answered is through models and theories that apply to the individual case. It is often said that practitioners avoid theory and philosophy in favor of actual clinical techniques, but an examination of popular psychology books read by practitioners shows that this is false. Practitioners need knowledge with scope, because they often face novel situations with unusual combinations of features. Popular books take advantage of this need by presenting fairly simplified models, often ones that can be expressed in a few acronyms, that claim to have broad applicability.

Broad models and theories are needed in the practice environment because they provide a basis for the use of knowledge when confronted with a new problem or situation, and suggest how to develop new kinds of practical techniques. In addition, because teaching based purely on techniques can become disorganized and incoherent as techniques proliferate, theory and models make scientific knowledge more teachable.

Book publishers, workshop organizers, and others in a position to know how practitioners usually react often cringe if researchers try to get too theoretical, but this makes sense given the kind of theories often promulgated by researchers, which are typically complicated, narrow, limited, and arcane. Worse, many theories do not tell clinicians what to do because they do not focus primarily on how to change external variables. Clinical theory is not an end in itself, and thus should not be concerned primarily about “understanding” separated from prediction and influence, nor primarily with the unobservable or unmanipulable.

To be practically useful, psychological theories and models must also be progressive, meaning that they evolve over time to raise new, interesting, and empirically productive questions that generate coherent data. It is especially useful if the model can be developed and modified to fit a variety of applied and basic issues. They also need to be as simple as possible, both in the sense that they are easy to learn and in the sense that they simplify complexity where that can be done.

Finally, to be truly useful, applied research must fit the practical and personal realities of the practice environment. It does no good to create technologies that no one will pay for, that are too complicated for systems of care to adopt, that do not connect with the personal experiences of practitioners, that are focused on methods of delivery that cannot be mounted, or that focus on targets of change that are not of importance. For that reason, applied psychology researchers must be intimately aware of what is happening in the world of practice (e.g., what is managed care?; how are practitioners paid?; what problems are most costly to systems of care?; and so on). The growth of websites, apps, bibliotherapy, peer support, and other ways of delivering psychological help indirectly is exploding. The expansion of psychology from mental health to physical and behavioral health, as well as social health in areas such as prejudice and stigma, is obvious.

2.3 Research of Importance

Putting all of these factors together, applied research programs that make a difference tend to reach the practitioner with a combination both of a technology and an underlying theory or model that illuminates how processes of change apply to the individual case and that is progressive, simplifying, fits with the practical realities of applied work, and is learnable, flexible, appealing, effective, broadly applicable, and important. This is a challenging formula, because it demands a wide range of skills from psychological researchers who hope to make an applied impact. Anyone can create a treatment and try to test it. Anyone can develop a narrow “model” and examine a few empirical implications. What is more difficult is figuring out how to develop broadly applicable models that are conceptually simple and interesting and that have clear and unexpected technological implications. Doing so requires living in both worlds: science and practice. The need for this breadth of focus also helps makes sense of the need for broad knowledge of psychological science that is often pursued in more scientifically based clinical programs.

3. The Practical Role of the Scientist-Practitioner