Introduction

In 2000, the European Union (EU) presented the Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC, introducing a detailed plan for improving the EU’s water quality to be implemented by the member states on 22 December 2003. However, some member states faced serious problems in incorporating the EU directive into their existing national laws. In the case of Germany, the European Commission started an infringement proceeding, and, in December 2005, the European Court of Justice ruled that Germany had failed to fulfill its obligations since five of its subnational states (Länder) did not comply in time. Notably, rather than the national executive, subnational authorities were the culprits. So, was federalism to blame? Or, to ask more generally: does the involvement of subnational authorities negatively affect the transposition of EU directives?

This article provides new and robust answers to the question by disentangling the subtle effects of federalism on directives implementation. Federalism (i.e., the institutional empowerment of subnational actors) has long been suspected of delaying transposition (e.g., König and Luetgert Reference König and Luetgert2009; Borghetto and Franchino Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010; Thomson Reference Thomson2010). However, merely a few studies open the “black box” of federalism and analyse the exact involvement of subnational authorities. First, most studies assume that federal states will always involve subnational authorities in implementing EU law and apply federalism indices to all of a country’s implementation measures. This assumption may err in two directions: transposition sometimes involves subnational authorities even in nonfederal states (see Borghetto and Franchino Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010), and sometimes national authorities in federal states may be exclusively responsible for the transposition of a directive (see Treib Reference Treib2014, 26). Moreover, the involvement of subnational authorities may take different routes on transposition performance. They may play a role in having direct implementing authority within their subnational territory, or in participating in the national transposition process as members of a second chamber. Second, many existing studies observe the very first (e.g., Luetgert and Dannwolf Reference Luetgert and Dannwolf2009; Zhelyazkova and Torenvlied Reference Zhelyazkova and Torenvlied2009; Haverland et al. Reference Haverland, Steunenberg and Waarden2011) or the very last (e.g., Spendzharova and Versluis Reference Spendzharova and Versluis2013) measure in a country, ignoring the potential variance of transposition performance across subnational units.

We innovate transposition research on both fronts. By using individual directives as unit of analysis, we provide a more robust assessment of federalism’s covariates. Our study focuses on the implementation of each directive at the national and subnational levels in Germany. Here, federalism may affect transposition along two different routes: first, by the use of the subnational actors’ power at the national level to either delay or veto decisions in the second chamber (Bundesrat) and second, during the transposition of EU directives on the subnational level. Our novel data set comprises all 1,950 reported national and subnational legislative implementation measures between 1990 and 2018 for 846 EU directives. We use binary logistic regression models to analyse the outcome of the transposition process in terms of either transposing on time or being delayed. We show that involving the subnational level indeed causes delays, while state-level variables may account for a large share of the variance. The descriptive results indicate that national legislation is delayed in 45% of the cases, whereas subnational legislation faces late transposition in about 90%. Furthermore, the analysis reveals that delay is more likely if subnational implementers adopt measures and if there is no exclusive national responsibility to act. Concerning the latter, the result also holds for severe delay cases and underlines the negative impact of multi-level systems on the duration of decision-making in general. However, the effect of the second chamber’s veto power remains inconclusive.

Our findings have implications for more general questions, such as how public policies adopted at higher levels are implemented and applied in multi-level political systems or the influence of the various implementing actors involved in the policy-making process (Cairney Reference Cairney2012). In political systems exhibiting vertical power separation between the national and subnational levels (see Knill and Tosun Reference Knill and Tosun2012), the success of implementation hinges on additional actors, such as the subnational parliaments and their executives. We show that implementation performance and efficiency are challenged due to the additional cooperation and collaboration requirements. In other words, while involving subnational units and parliaments may enhance legitimacy (see Sprungk Reference Sprungk2013), it imposes practical hurdles on efficient policy-making due to time-consuming procedures (e.g., Falkner Reference Falkner, Zahariadis and Buonanno2018, 328).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. After revisiting existing research on the role of subnational authorities in the EU implementation deficit, we present our theoretical argument opening the black box of federalism. We then discuss our research design, the data, and the operationalization of the covariates. The empirical analysis presents descriptive insights and the results of the logistic regression models. Finally, we critically discuss our results and sketch avenues for future research.

The EU “Implementation Deficit” and the role of subnational authorities

The EU implementation process is characterised as a multi-level policy cycle: the European level is entrusted with policy formulation and decision via EU directives, while it is the fundamental responsibility of the member states to transpose them into their national laws. Accordingly, the compliance literature conceptualises policy implementation as a multi-stage process. Van Meter and van Horn (Reference van Meter and van Horn1975, 448) describe them as “policy implementation, performance and … policy impact”. This conceptual distinction is reflected in the terminology of legal and practical implementation (e.g., Versluis et al. Reference Versluis, van Keulen and Stephenson2011, 183f) and structures our interest in transposition performance: how do implementing actors perform on the stages of the implementation process? Whereas early studies analyse deficits in legal implementation (Mastenbroek Reference Mastenbroek2005; Haverland et al. Reference Haverland, Steunenberg and Waarden2011), recent research brings in practical implementation (e.g., Zhelyazkova et al. Reference Zhelyazkova, Kaya and Schrama2016; Gollata and Newig Reference Gollata and Newig2017). However, practical implementation can only take place once the anterior stage of implementation is completed. Our empirical focus hence lies in timely transposition as one central indicator for effective implementation performance. Though some question the statistical relevance of an implementation deficit (Börzel Reference Börzel2011; Angelova et al. Reference Angelova, Dannwolf and König2012), we are confident that our detailed analysis of the level of individual directives provides for relevant insights on the performance record in federal systems.

In the following, we develop a number of hypotheses on the variation in transposition delay in multi-level political systems. These hypotheses are derived from theoretical discussions in EU implementation stemming from compliance research in international relations (Chayes and Chayes Reference Chayes and Chayes1993) as well as in the research on public policy and implementation (Pressman and Wildavsky Reference Pressman and Wildavsky1974). Whereas the management approaches argue that the implementation performance is dependent on the state’s capacity to act, the enforcement approaches focus on preferences and the state’s willingness to comply (see Treib Reference Treib2014, 11). Additionally, legitimacy approaches stress the normative belief system and the acceptance of rules as a key driver in complying (see Börzel et al. Reference Börzel, Hofmann, Panke and Sprungk2010, 1370f). These approaches have led to a number of explanatory factors.

The scholarly literature differentiates between three factors influencing transposition performance: EU level (Franchino and Høyland Reference Franchino and Høyland2009), domestic level (Sprungk Reference Sprungk2013; Dörrenbächer et al. Reference Dörrenbächer, Mastenbroek and Toshkov2015), and sectoral factors comprising policy-specific variables. With regard to domestic factors, the literature has exclusively focussed on the national level for a long time. This is hardly surprising as implementation research originated in the context of nation-states (Versluis et al. Reference Versluis, van Keulen and Stephenson2011, 187) as well as in the compliance research in international relations (for a review of EU implementation research, see Treib Reference Treib2014, 7ff). Subsequent qualitative research turned to the influence of the subnational level in different policy domains. Milio (Reference Milio2007) presents one of the first studies in this area and uncovers that the varying subnational implementation of EU Structural Funds could be attributed to the differences in the administrative capacities of Italian regions. Gollata and Newig (Reference Gollata and Newig2017) examine the concept of “multi-level governance as implementation strategy” at the subnational level and find variation in the practical implementation of environmental directives in the German Länder due to the subnational arrangements with regard to decentralisation, spatial fit and participation approach. Barbehön (Reference Barbehön2016) expands the scope to local implementation and analyses how discursive arguments shape the practical implementation on the “street-level”.

Besides these subnational differences in the policy output, one general expectation of the literature propounds that federalism may delay the transposition of directives in general. On a more abstract level, Hill and Hupe (Reference Hill and Hupe2003, 472) point out that policy harmonisation may be hampered by a “multi-layer problem” that arises when different formal political-administrative institutions come into play. As a multi-level polity, the EU may be particularly prone to such challenges. Complementing national actors with subnational ones may reinforce the problem. The management approach identifies the involvement of subnational authorities as another factor hindering a state’s ability to comply with the obligations under the directives (Börzel et al. Reference Börzel, Hofmann, Panke and Sprungk2010, 1369f).

The suspicion against federalism as a source of delay is largely corroborated by existing studies (overview see Toshkov Reference Toshkov2010, 24; Treib Reference Treib2014, 25f). In one of the very first studies, Mbaye (Reference Mbaye2001) finds that a higher degree of regional autonomy is associated with more infringement proceedings by the Commission. This negative effect on the implementation record is confirmed by numerous authors (e.g., Linos Reference Linos2007; Thomson 2007; Reference Thomson2010; König and Luetgert Reference König and Luetgert2009), who analyse the duration of the transposition process. Even though the result is not disputed in the literature, some studies do not hint at significant effects (e.g., Haverland and Romeijn Reference Haverland and Romeijn2007; Jensen Reference Jensen2007; Steunenberg and Toshkov Reference Steunenberg and Toshkov2009). Overall, these findings suggest a negative impact of federalism or regionalism on the transposition record of member states (e.g., Linos Reference Linos2007; König and Luetgert Reference König and Luetgert2009; Borghetto and Franchino Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010; Thomson Reference Thomson2010). However, most studies only look at the impact of federalism on an aggregated level and apply general indices on federalism or regionalism to all of a country’s transposition workload. Treib (Reference Treib2014, 26), however, emphasises that federalism does not always play a role as the central government may sometimes be exclusively responsible for adopting the implementation measure. Hence, a disaggregated look at individual directives and how they are affected by federalism promises more reliable insights. We provide such a look by opening the “black box” of federalism. Our theoretical perspective is mainly inspired by the arguments of the management approaches.

Federalism may delay transposition along several causal paths. First, a transactional delay may be caused by the fact that the participation of another level “complicates the transposition process” (Haverland and Romeijn Reference Haverland and Romeijn2007, 773) and will make it more likely to “exhibit compliance problems” (Thomson Reference Thomson2010, 591). An extended transposition process seems plausible since the subnational authorities will have to take actions that may involve additional actors, such as subnational parliaments and executives. Moreover, the bureaucratic capacities may vary across these actors, influencing a timely and legalistically correct implementation. Borghetto and Franchino (Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010) demonstrate that the argument may be generalised beyond federal countries, as transposition frequently brings in subnational authorities. Besides federalist member states, such as Belgium, Austria and Germany, this applies to Finland, Italy, or the United Kingdom, where the subnational units participate in implementing EU laws.

Second, the intentional action of subnational authorities may cause a transposition delay. Various studies shed light on the political role of subnational authorities in the implementation process. The literature on gold-plating (e.g., Kaeding Reference Kaeding2008; Morris Reference Morris2011; Thomann Reference Thomann2015) revealed how national-level actors try to impose their own policy preferences by implementing directives in a specific manner. This intuition similarly applies to the subnational level. Auel and Große Hüttmann (Reference Auel, Große Hüttmann, Abels and Eppler2015, 352) emphasise the political interest of subnational actors to directly shape policies in the implementation process and corroborate that “the role of subnational parliaments in EU politics is not exhausted by acting as watchdogs of their governments”. On the contrary, they are active policy shapers in certain policy areas. EU provisions might not be in line with predominant subnational interests and could incentivise strategies to delay and/or amend implementation. Both arguments on transactional and intentional delay lead to our first hypothesis:

H1: [Subnational Implementer hypothesis] If the subnational level implements directives, transposition is more likely to be delayed as compared to implementation at the national level.

In federal systems, the legislative process is not exclusively steered at the national level. National and subnational units share the right to initiate and adopt bills. Some legal competences can be exclusively located at either the national or subnational levels, whereas others may be mutual in certain policy areas (Biela et al. Reference Biela, Hennl and Kaiser2013; Behnke and Kropp Reference Behnke and Kropp2016). Hence, some directives may require unilateral action of the national government; others may involve both national and subnational executives and parliaments. Ultimately, certain policy areas may exclusively allow subnational actors to adopt implementation measures. Hence, there are three theoretical constellations in the allocation of implementation responsibilities in multi-level political systems: the responsibility may be exclusively national or subnational or shared between national and subnational levels. Each of these constellations invites different theoretical expectations. Overall, we expect the national level to be particularly well equipped for a speedy transposition. In the EU context, the national level enjoys informational advantages when it comes to complying with EU directives. The national government is better informed about the negotiation process of EU laws as it is represented in the Council. It will be aware of upcoming EU laws and prestructure its legislative business. Hence, we expect that transposition will be faster if it lies within the exclusive competence at the national level. Once the implementation is located at the national and subnational levels, we expect to find more transposition delay compared to the exclusive national implementation due to the coordination of additional actors and different levels of information. Concerning the exclusive competence at the subnational level, we expect to find more delay than in the case of the national exclusive responsibility. In this case, the subnational actors have to comply with EU policy goals separately, making it a multi-actor implementation process of various units. Furthermore, subnational actors are not represented in EU policy formulation and face asymmetrical information and resource restrictions in EU affairs compared to the national actors. Hence, subnational units may face additional challenges in the transposition process. This leads to the following hypotheses on transposition responsibilities:

H2: [National responsibility hypothesis] Exclusive implementation at the national level is speedier than shared (national and subnational) or exclusive subnational implementation.

Federalism may not only set the stage for subnational authorities as important implementers of directives. Subnational actors may also play an important role on the national level. A powerful second chamber, such as the German Bundesrat or the Italian Senate (e.g., Gazzola et al. Reference Gazzola, Caramaschi and Fischer2004), may provide subnational actors with the opportunity to influence the policy formulation of transposition measures. This is particularly true if the second chamber has considerable veto or delaying powers. We expect that the participation of the subnational level via the second chamber is likely to prolong the transposition process whenever it has the right to veto the legislative proposal. In fact, König and Mäder (Reference König and Mäder2014, 247) model implementation as a “strategic game” between the Commission and the member states. When additional veto players enter this game in the member states, they pursue their own goals, introduce new lines of conflict, and influence the outcome. The policy effects of bicameralism are demonstrated in various quantitative studies (e.g., Franchino and Høyland Reference Franchino and Høyland2009; König and Luig Reference König and Luig2014).

In addition, qualitative case study research corroborates the influence of second chambers on implementation. Haverland (Reference Haverland2000) demonstrates the essential influence of institutional veto points on the transposition of an environmental directive in Germany, among others, and finds a negative impact on the timeliness of the transposition process. In the German case study, the parliamentary opposition was able to block the government’s policy proposal in the second chamber (Bundesrat) due to the majoritarian composition in the house. Bähr (Reference Bähr2006) confirms this finding and underlines the veto power to block the decision-making process in federal systems that ultimately also delays transposition. This results in our third hypothesis:

H3: [Second chamber hypothesis] The veto power of the second chamber is likely to delay the transposition process.

Research design

Case selection

We study the EU implementation process in Germany’s multi-level polity, which provides us with a fruitful testing ground for our research interest. Germany’s polity is characterised by the so-called cooperative federalism (in detail Auel Reference Auel2014) with a “functional division of powers between central legislation and decentralised administration” (Benz Reference Benz2015, 15). Legislative powers over the most salient policy areas, such as labour, social policy, and taxes, are centralised at the national level, and the subnational states (Länder) have mainly prerogatives in implementing laws. Nevertheless, the Länder still have the exclusive legislative power in some policy areas (e.g. higher education, police), whereas they share competences with the national level in others (e.g., agriculture). Accordingly, there are various constellations of shared and unilateral responsibilities in order to study the effects of interest.Footnote 1

Federalism in Germany implies that the Länder participate in implementing directives at the national level via the second chamber (Bundesrat). Two kinds of bills are relevant in determining the actual power of the Bundesrat: on the one hand, the Bundesrat enjoys absolute veto power over the so-called consent bills (Zustimmungsgesetze). To become law, an absolute majority in the Bundesrat has to approve such a bill. On the other hand, the Bundesrat may register objections to so-called objection bills (Einspruchsgesetze). However, this objection is only suspensive and can be overruled by an absolute majority in the German Bundestag.

Moreover, Germany is well suited to illustrate the effects of federalism on transposition performance due to two analytical reasons. First, it provides ideal conditions for a controlled comparison of the subnational polities. The political process in the sixteen Länder is very similar, and their legislative procedures follow the same principles. Whenever the Länder act within their exclusive or shared responsibility, they are bound by their subnational constitutional setting. For example, the constitution of Bavaria sets out the legislative process in its parliament, which is, in general, comparable to the national legislative process. Similarly, legislative proposals can be introduced by the executive and the parliamentary parties. Second, the Bundesrat as the second chamber is composed of the representatives of the subnational governments. Even though the Länder executives often consist of coalition governments, every Land has to vote en bloc in the second chamber.

Even though Germany is a typical case with respect to its federal and bicameral political system, the single country research design has limitations too. As the number of (semi-)federal states in the EU is limited, our results rather set the ground for future research on the different roads of subnational involvement in EU policy implementation. Nevertheless, our results additionally speak to the general literature on policy-making in federal systems that are characterised by multi-level implementation of public policies. Beyond the influence of second chambers, we highlight the temporal challenges in multi-level decision-making beyond the exclusive national responsibility to comply with public policies.

Data

This article introduces an original data set on EU implementation in Germany between 1990 and 2018. We compiled the data from EU-based and national-based resources. First, we collected directives published on EUR-Lex between 1990 and 2016.Footnote 2 Second, we extracted all reported national and subnational implementation measures in Germany based on EUR-Lex. We collected the last data on 20 February 2018 to be able to pick up reasonably delayed cases. In order to analyse the effect of our three state-level variables, we restrict our analysis to primary legislation [i.e. laws (Gesetze)].Footnote 3 The data covers 846 EU directives and 1,950 German implementation laws at the national and subnational levels.

Our dependent variable measures the timeliness of the transposition process of each implementation measure. While previous studies discuss whether the very first or the very last measure should be considered (e.g., Berglund et al. Reference Berglund, Gange and Waarden2006, 697), we observe the entire implementation process at the national and subnational levels. Restricting the analysis to the first or last measure would exclude most of the cases we are actually interested in: gauging the subnational influence via the different routes. We code Delay as a dichotomous variable with respect to the entire transposition process of directives. As reference points, we use the directive deadline, which stipulates the time until EU provisions have to be complied with in the member states, and the notification by the German authorities to the Commission. The variable Delay is coded as one whenever the member state has notified a measure after the EU directive’s deadline and as zero in timely transposition cases.

To be frank, our data on the timeliness of transposition raises some methodological problems. Whenever more than one implementation measure is adopted, a problem of interdependence could arise. For example, it might be the case that the subnational level has to await transposition initiatives at the national level that would leave subnational actors no choice but to prolong the process. In addition, the question arises whether the different implementation measures for one directive correspond to package deals that enter into force collectively.

Yet, these potential problems seem to play a minor role when inspecting the qualitative and quantitative data: in fact, the subnational level can initiate the legal implementation process in close proximity to the activities at the national level. A descriptive inspection of implementing measures for each directive does not hint towards a chronological leadership of the national level in the sequences of transposition measures. On the contrary, the subnational level frequently starts the process in advance or contemporaneously to the national level. From a legalistic perspective, this finding is in line with the argument of a strong role of the Länder in policy areas that touch their competences.Footnote 4 This first result indicates that the subnational level is quite independent in the initiation of the transposition process and hence facing delay. Note that the constitutional provisions rather grant them room for manoeuvre.

The independent variable Subnational Implementer identifies the level of the implementation measure. It is coded as zero if the national level (Bund) is the implementer of a measure and as one if one of the sixteen German subnational states (Länder) is involved. Furthermore, the variable Responsibility traces the distribution of competences and is coded as one if there is an exclusive responsibility at the national level, and zero otherwise. The latter category can include the shared competence between the national and subnational levels and the exclusive competence at the subnational level.Footnote 5 In addition, the variable Second chamber refers to the influence of the subnational level during the national legislative process via the Bundesrat. It takes the value one if the Länder control a veto over the transposition bill in the second chamber, and zero otherwise. We collected the information on the veto power of the second chamber from the documentation system of the German Bundestag (see Stecker Reference Stecker2016).

In line with the different EU implementation approaches, we do not only expect an influence of federal institutional factors on the transposition delay. We derive five control variables from the broader literature that pertain to characteristics at the EU and national level and may influence the implementation performance. In order to account for the domestic legislation in member states, we first acknowledge that member states may notify implementation measures that have already been in force before the adoption of the EU directive. Facing a better policy fit, member states are generally less likely to prolong the transposition process in these circumstances (Sprungk Reference Sprungk2013, 302). Prelegislation controls for existing measures in the member state. It is coded as one if the implementation measure predates the adoption of the directive, and zero otherwise.

Furthermore, existing literature (e.g., Toshkov Reference Toshkov2010; Treib Reference Treib2014) points to the influence of differences among the directives on implementation. Second, we control for the time that is granted to the member states to comply with policy goals. Whenever member states face short deadlines, they are under time pressure and are more likely to delay the transposition (see Franchino and Høyland Reference Franchino and Høyland2009). Deadline measures the years between the adoption of the directive and its transposition deadline. Third, EU Agent controls for the EU decision-making procedure. We distinguish between Commission directives, Council directives and directives from the Council and the European Parliament. As Commission directives frequently specify technical details that are less controversial, they are associated with faster transposition compared to both alternative types of directives (see Haverland et al. Reference Haverland, Steunenberg and Waarden2011).

Fourth, we control for the degree of Complexity since some directives set higher workloads on member states than others. The number of recitals is commonly used in the literature (see Treib Reference Treib2014, 27) to indicate the difficulty of directives in the implementation process. Finally, we include the Policy Sector as a control variable. Previous research indicates cross-sectoral variation in implementation (e.g., Haverland et al. Reference Haverland, Steunenberg and Waarden2011) that may additionally influence the transposition delay.

Results

Descriptive results

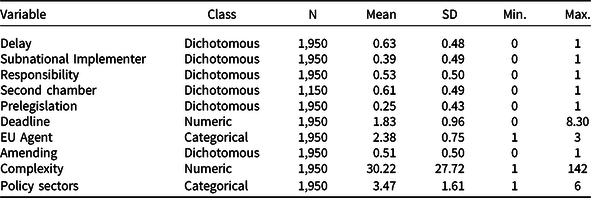

Table 1 summarises the descriptive statistics. Out of 1,950 legislative measures, 63% fall in the category of late transposition. In addition, we find that 39% of the implementation measures originate at the subnational level. This underlines the importance of the subnational level as an implementer of EU directives. Subnational parliaments and their governments can play a decisive role in the EU multi-level policy cycle and may actively shape the implementation process. Subnational parliaments may, hence, use the EU implementation process as a means to leave their “Life in the Shadow” (Auel and Große Hüttmann Reference Auel, Große Hüttmann, Abels and Eppler2015, 345) and compensate for the loss of competences in the national legislative process.

Table 1. Descriptive results

Once we compare transposition performance at the national and subnational level, the picture is unambiguous. Transposition is delayed in 45% of the 1,192 national measures. The record is tremendously worse at the subnational level, where measures are delayed in 90%. It points to serious problems in the implementation process whenever the subnational authorities are involved with severe consequences for Germany’s overall transposition record. In the introductory example, the Commission accused five Länder of noncompliance with the Water Framework Directive. The timely transposition at the national level could not exonerate Germany from failing to fulfill its obligations under the directive. These cases of mixed responsibilities provide fruitful insights into the mechanisms causing late transposition and making Germany one of the laggards in EU implementation (see, e.g., Börzel and Knoll Reference Börzel and Knoll2012).

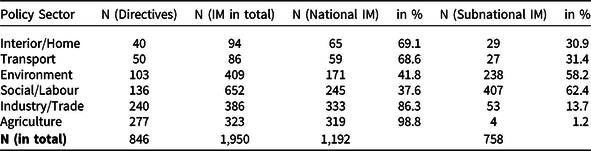

Table 2 presents the distribution of directives and their corresponding implementation measures in the six policy sectors. Between 1990 and 2016, 277 directives in agriculture make up the biggest share and account for 33%. A minimum of 40 directives occur in interior and home policies. With regard to the implementation of all directives, a maximum of 652 measures was notified in social and labour policies. A minimum of 86 measures relate to transport policies. Once we compare the number of directives and their corresponding implementation measures, certain policy sectors seem to require a greater number of implementing measures. For example, environmental and social/labour directives lead to more than twice as many measures compared to agricultural and industry/trade directives. It seems plausible that certain policy sectors will regulate adjoining policy fields and lead to numerous aligning measures.

Table 2. Distribution of implementation measures by policy sector and implementer

Note: IM = Implementation measures.

In addition, certain policy sectors tend to require subnational implementation measures more than others. Figure 1 presents the number of national and subnational implementation measures in each of the six policy sectors. Directives on social and labour policies are predominantly transposed via subnational measures, whereas agriculture almost exclusively activates the national level. This is in line with our initial expectation that the responsibility to comply with EU provisions at the subnational level is restricted to certain policy areas. The distribution of measures at the national and subnational levels allows for the following conclusion: the policy sectors in the environment and social/labour are highly regulated by the subnational authorities. They each make up about 60% of all measures.

Figure 1. Implementation measures by implementer and policy sector.

Finally, note that there is a considerable variation in the share of late implementation among the different policy sectors. There is just one policy sector with a positive transposition record. In total, 89% of all implementation measures in agriculture are on time. The five remaining policy sectors face late transposition in more than half of the cases. The two worst records of delay stand out with 83% in the environment and 90% in interior and home affairs. These patterns invite some speculation. The delay-prone policy sectors could feature complex provisions that demand higher capacities in terms of staff and expertise on the part of the implementers. The respective policy fields may also exhibit higher levels of policy conflict and bring in the diverging policy preferences of the different actors. Implementers may pursue delaying strategies, and negotiations among the different implementers in disagreement may take longer. These questions are, however, beyond the focus of this research article.

Analysis

In the following, we present a more rigorous test of our hypotheses. Due to the binary nature of the dependent variable Delay, we use logistic regression modelsFootnote 6. Model 1 tests the hypotheses on Subnational Implementer and Responsibility and includes the control variables at the level of the member state and the EU. Model 2 implements a rigid test on severe delay (i.e., cases that have been delayed for more than one and a half years) to evaluate how far our results in Model 1 hold over time. We cluster the standard errors at the level of directives to account for the nested data structure in all presented models. Figure 2 below presents the results as coefficient plots for Delay in Model 1 and Model 2 for the key variables, which both pass the chi-square test and are significant.Footnote 7 Table A in the appendix presents the full models in detail.

Figure 2. Coefficient plots for Delay in odds ratios.

Note: Confidence intervals are cut off at the scale of eight to ease visibility; Reference category in EU Agent: Commission directives; Standard errors (clustered on directives) and full models see appendix.

Starting with the results for the logistic regression of Delay in Model 1, both our main variables Subnational Implementer and National Responsibility hint in the right direction and are statistically significant. The result of Subnational Implementer shows that the odds of transposition delay are about three times higher for subnational measures than for national measures. Referring to the predicted probabilities, the risk of Delay at the national level is 61% and 82% at the subnational level if all other variables are kept at their mean values. Hence, the probability of late transposition is 20% higher at the subnational level. In sum, about 90% of the subnational laws are adopted after the transposition deadline. In federal systems, the involvement of the subnational level is a delaying factor that can ultimately lead to infringement proceedings by the Commission. This finding lends support to the first hypothesis on the subnational involvement in the transposition process. It is also in line with previous results by Borghetto and Franchino (Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010), who found a delaying effect on transposition once subnational units are involved. It raises serious concerns about the effectiveness in multi-level systems: additional actors and institutional hurdles in policy-making have their cost (i.e. prolonging the decision-making process).

Next, Responsibility is statistically significant and points into the expected direction. The odds of late transposition for the exclusive competence at the national level are about 64% lower compared to shared or subnational exclusive competences. This implies that the national duty to comply with EU laws decreases the risk of delay. Looking at the predicted probabilities, late transposition is even 21% less likely to occur in cases of exclusive national responsibilities. Intuitively, it seems reasonable to detect fewer cases of late transposition than in shared responsibilities whenever it is exclusively up to the national actors to coordinate and take implementation measures. In this scenario, no additional subnational legislators are involved that might prolong the process.

However, it seems less intuitive to discern the pattern for transposition procedures in cases of shared or exclusive subnational responsibilities. Two lines of arguments seem plausible: on the one hand, late transposition should be less likely in exclusive subnational responsibilities compared to cases of shared responsibilities. In the latter scenario, national and subnational implementers have to coordinate and organise the implementation, which could further delay the process. Once it is exclusively up to the subnational level, it should have a similar pattern compared to the national responsibility and lead to less delay. The sixteen states are independently adopting measures and do not have to coordinate among themselves or with the national level.

On the other hand, the delaying influence in subnational responsibilities might be due to less information and fewer capacities in EU affairs compared to the national level. Representatives of the national government take part in the Council meetings and will hence have better access to upcoming EU obligations. In addition, the need to adopt measures in each of the subnational units may overall increase the risk of delay simply due to the increased number of actors that are involved in the process. The descriptive statistics of the data illustrate that about 53% of all implementation measures fall within the exclusive national competence. Disentangling the measures in the category of shared and subnational responsibilities, the mixed competence accounts for 95%. The exclusive subnational competence is hence a rare case in the data, equalling 46 implementation measures for a total of seven EU directives. The low distribution of the latter also excludes the categorical separation in the analysis and stands against an individual test in the model. Nevertheless, the descriptive statistics point to a higher percentage in late transposition whenever national implementers are not exclusively involved. If there is a national responsibility to transpose, 60% of the cases are on time. Once the subnational level is involved via the shared or subnational competence, the quota drops tremendously to 12% and hints at a strong delaying effect. Overall, the result supports our second hypothesis and is in line with previous studies that account for institutional factors such as federalism (e.g. Linos Reference Linos2007; König and Luetgert Reference König and Luetgert2009).

In short, we can conclude that the transposition delay is explained by our two main factors in combination with the controls.Footnote 8 With regard to the controls at the member state and EU level, all factors are statistically significant except for the complexity and policy sectors. In the latter, one category did not turn out significant in relation to the reference category (i.e. agriculture). Turning to Prelegislation, notifying a pre-existing measure to the Commission is highly statistically significant. The odds of late transposition decrease by 79% if the member state notifies a measure that is already in force preceding the directive compared to notifying newly adopted measures. However, apart from signalling a better policy fit, notifying pre-existing measures has raised doubts about noncompliance. It might simply be a strategic “cheap talk” (Zhelyazkova and Yordanova Reference Zhelyazkova and Yordanova2015, 423) and rather indicates problems in complying. In addition, we controlled for EU level factors. The results for Deadline (i.e. the time until member states have to comply with the EU directive) are statistically significant. Overall, the results point to a positive effect of an extended deadline on delay. In other words, having more time in the implementation process makes delay less likely.

Furthermore, the EU Agent adopting the directive has a significant effect on delay. The reference category being Commission directives, we find that Council directives accelerate transposition. The odds of delay for Council directives are 50% lower compared to Commission directives. In contrast, the odds of delay are more than six times higher for Council and European Parliament directives than for Commission directives. These results partially point into a different direction than in previous findings. Council directives are expected to be more likely to cause delay compared to Commission directives (e.g., Borghetto and Franchino Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010). Contrary to the expectation, the risk of delay for Council directives is 17% lower than in the case of Commission directives. One line of argument could be the following: the technical details of Commission directives might challenge legislators during the implementation process in adapting their national provisions.

Next, Complexity does not point into the expected direction and is not significant in Model 1. Finally, Policy Sector controls for the different policy areas and provides mixed results. The reference category being agriculture, we find that all policy areas are more likely to experience delay except for social and labour policies, which did not turn out significant. Agriculture is one of the oldest policy fields in EU decision making and is a highly routinised domain with little conflict. In comparison, the other policy sectors are not as standardised and can potentially involve controversial aspects that might cause a delaying effect in the transposition.

The results on Model 1 pertain to a general measuring approach on delay without differentiating between cases of moderate and severe delay. Model 2 incorporates a more rigid measure by taking a delay of more than one and a half years as a cut-off point (see Figure 2 and in the appendix). Applying the same model specification otherwise used in Model 1, we find in Model 2 that participation of Subnational Implementers is no longer statistically significant and does not show the expected effect. Apparently, in cases of severe delay, the responsible actors’ position within the multi-level system does not seem to matter. This result suggests that severe delay is usually associated with compliance problems that may arise at each level of policy implementation. Nevertheless, the descriptive statistics hint at differences in the transposition performance between the subnational units in general. For example, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, Rhineland Palatinate and Saxony Anhalt appear to be the laggards – on an average they face severe delay in more than 40% of the cases. This indicates that the subnational units within a member state may not face the same challenges when it comes to transposition.

With respect to our hypothesis on responsibilities, the result remains significant for severe delay indicating that the national exclusive responsibility still speeds up transposition. The probability of severe delay is 23% lower. This result corroborates the delaying effect of involving the subnational unit in policy implementation in general. Facing severe delay, it is the combination of actors that leads to compliance problems by activating additional coordination mechanisms. The finding confirms previous results that identify a negative influence of institutional factors on policy implementation such as federalism (e.g. Mbaye Reference Mbaye2001; Börzel et al. Reference Börzel, Hofmann, Panke and Sprungk2010). Moving beyond general indices, our results underline the importance of differentiating between the allocation of responsibilities in multi-level political systems. The federal characteristic per se does not lead to delays in transposition. It is rather the case-specific constellation of actors that are involved in the process. Whereas this result generally supports the argument of the management school on the negative impact of domestic factors on the capacity of the state to act, it does not account for the policy preferences of the actors that may negatively impact the transposition.

As previously stated, our model does not differentiate between the shared and subnational exclusive responsibility to comply with EU policy goals. At this point, we can only theoretically speculate about the implications with respect to preferences and the constellations of actors between the different levels. Regarding the controls, they mainly support the previous considerations and underline that policy sectors do no longer play a decisive role. Contrary to this notion, the complexity of directives now turns out significant and actually speeds up transposition.

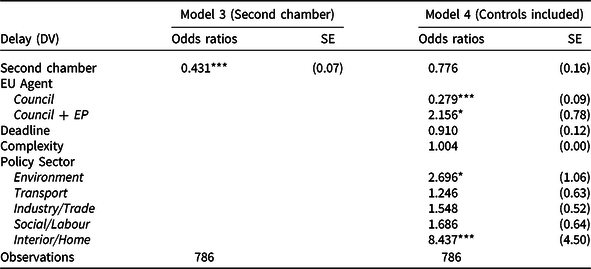

To assess the influence of the second chamber on Delay in the transposition process, we test our third hypothesis on all newly adopted legislative implementation measures at the national level. We exclude all subnational measures since the second chamber has an exclusive veto right for national legislation. Model 3 only includes the variable Second chamber, whereas Model 4 incorporates the controls at the EU level. Table 3 presents the results for both model specifications. In Model 3, we find that the veto power in the national legislative process is indeed highly statistically significant. The average odds ratio for the veto power of the second chamber is 0.43. Hence the odds of late transposition of a consent bill at the national level are about 57% lower than in the reference category of objection bills. In other words, the result suggests that passing an objection bill (without the veto threat) is more likely to be delayed. In terms of predicted probabilities on Delay, we find that the consent bill is about 20% less likely to be late in the transposition. However, the effect points in the opposite direction as we initially expected.

Table 3. Logistic regression results on Delay for the second chamber

Note: Exponentiated coefficients; Standard errors (clustered on directives) in parentheses.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

In contrast to the results of Model 3, we do not find a statistically significant result for the Second chamber variable once we add the controls in Model 4. Model 3 and Model 4 raise the question about the direction of the effect and the significance of the results in general. It seems to point into a less pronounced effect as initially expected. The descriptive results reveal that 71% of the objection bills are delayed and half of the consent bills as well. The following question arises: are there different mechanisms conceivable that cause objection bills’ higher risk of delay?

For instance, Burger and Zoller (Reference Burger and Zoller2012) demonstrate the role of the German second chamber on bills in relation to the Greek financial rescue mechanisms in 2010. Even though the second chamber could merely voice its objection and did not have a veto power via the consent bill, the Bundesrat published different statements demanding more influence in the matter and increased the political pressure. In EU affairs, the second chamber might be faced with the challenge of compensating the informational advantage of the national government. This might have led to informal coordination mechanisms between both chambers that have an effect on the timing of the legislative process. However, these considerations rather point to the need for qualitative interviews that can unveil the mechanisms between both chambers and the effect on the transposition process.

Conclusion

This article contributed to the debate on the effects of federalism during the multi-level implementation process in the EU. It adds to recent contributions (e.g., Borghetto and Franchino Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010; Auel and Große Hüttmann Reference Auel, Große Hüttmann, Abels and Eppler2015) that point to the evolving role of subnational authorities within the member states and their importance for timely and correct transposition. Many studies identify federalism as a central delaying factor (Haverland and Romeijn Reference Haverland and Romeijn2007; König and Luetgert Reference König and Luetgert2009; Thomson Reference Thomson2010). However, the empirical precision of these studies leaves room for improvement: mostly, they apply indices of federalism to the entire implementation workload of a country, while the actual involvement of subnational units varies across directives (Borghetto and Franchino Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010). We address this shortcoming and shift the level of analysis to each individual implementation measure and investigate the specific covariates of federalism, such as the involvement of subnational authorities and second chambers.

The empirical analysis uses an original data set on the 1,950 reported national and subnational legislative implementation measures for 846 EU directives in Germany between 1990 and 2018. Our findings mainly support the arguments of the management school on the negative impact of institutional factors such as federalism and underline the central influence of domestic factors on policy implementation. We show that the sixteen German subnational states are responsible for more than one-third of all implementation measures and also find that the subnational level is the main culprit for transposition delay. As additional actors, subnational authorities seem to lower the ability of the state to act and to decide on how to comply with EU directives. When subnational parliaments join national actors in the implementation process, they bring in their own policy preferences and strategic motives for either complying or prolonging the process. Only exclusive implementation competences at the national level exert a positive effect on timely transposition. This result also holds for cases of severe delay and underlines the importance of differentiating between the allocation of responsibilities in multi-level political systems.

Furthermore, federalism adds an additional player to the implementation process on the national level – but the results on the involvement of the second chamber remain inconclusive. On the one hand, this might point to a less pronounced influence of the second chamber in the transposition process than the literature argues. On the other hand, more studies are needed to unveil the coordination structures between both chambers in EU affairs and hence deepen our understanding of the legislative mechanisms. Our analysis of Germany as a typical case with respect to its federal and bicameral political system is a fruitful starting point for a thorough investigation of the causal pathways working on the level of individual implementation measures. Our results may also inform debates on subnational implementation that is often envisaged in nonfederal systems (e.g., Borghetto and Franchino Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010). Yet, this generalisability remains to be corroborated by future studies.

Overall, this study contributes to two broader research areas. It extends our understanding of implementing public policies in multi-level political systems (Cairney Reference Cairney2012) and adds to the discourse on efficient implementation performance in general. Involving subnational units may bring in additional legitimacy but also inefficiencies due to multiplied cooperation and collaboration procedures that – in the long run – may also endanger the overall functioning of the political system of the EU (e.g., Falkner Reference Falkner, Zahariadis and Buonanno2018, 328).

Our results raise some interesting avenues for future research. To begin with, it seems worthwhile to extend our focus on individual implementation. Recent research (e.g., Borghetto and Franchino Reference Borghetto and Franchino2010) has shown that numerous – even nonfederal – EU member states involve their subnational authorities and have an influence on the effective implementation performance. Moreover, we need further investigation of why the subnational level seems to have serious problems in the timely transposition of EU directives and how this explains the overall transposition delay. As the descriptive data shows, the subnational level is not dependent on the national level in the initiation of the subnational implementation process. Nevertheless, the risk of delay is tremendously higher. Lastly, how can we account for the variance in transposition performance across subnational units? Do they use different implementation styles? Do they vary in the practical application? While our article has given the first answers to these questions, much remains to be done in opening the “black box” of federalism in the research on EU transposition.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X20000276

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant number STE 2353/1-1). We thank four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Data Availability Statement

The replication files for the empirical data analysis can be found on the Harvard Dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/JUVCNJ.