The Nature of Social Anxiety

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) involves a marked and persistent irrational fear of being scrutinised or negatively evaluated in interpersonal and/or performance-based social situations (DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In such situations, an individual fears that s/he will act in a way that will be humiliating or embarrassing and therefore avoids or endures interpersonal and/or performance-based social situations with intense anxiety. Symptoms of social anxiety include cognitive, affective, behavioural, and physiological components (Lehrer & Woolfolk, Reference Lehrer and Woolfolk1982), and may be present prior to, during, and following a social or performance situation (Wells & Clark, Reference Wells, Clark and Davey1997).

In Australia, SAD has a 12-month and lifetime prevalence rate of 4.7% and 10.6% respectively, with higher prevalence in females (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2007). SAD is the fourth most common psychiatric disorder following harmful alcohol use, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and depression (ABS, 2007), and is commonly comorbid with other psychiatric disorders (Stein & Stein, Reference Stein and Stein2008). SAD typically has an early onset (often beginning in childhood or early adolescence) and is considered moderately heritable (Stein & Stein, Reference Stein and Stein2008). Despite the considerable suffering and functional impairment associated with SAD (including work, social life, family life), fewer than half of individuals with the disorder ever seek treatment, and only do so after 15–20 years of symptoms (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lane, Olfson, Pincus, Wells and Kessler2005).

Self-Focused Cognitive Processes in Models of Social Anxiety

Cognitive models of social anxiety have identified several mechanisms that account for the persistence of the disorder (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2007; Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). Maintaining processes within these models include self-focused attention and the construction of a mental representation of the self as a social object, heightened monitoring of external threat, in-situation safety behaviours and event avoidance, anticipatory and post-event rumination, comparison of one's mental self-representation with appraisal of the audience's expected standard, judgment of the probability and consequence of negative evaluation, and anxiety-induced performance deficits (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). These models suggest that self-focused cognitive processes are key to the generation and maintenance of anxiety experienced in social and performance situations. Specifically, Clark and Wells (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) suggest that socially anxious individuals engage in self-focused cognition not only during social situations (self-focused attention; SFA), but also prior to (anticipatory rumination; AR) and following social situations (post-event rumination; PER).

Aims and Methodology

Given the theoretical and empirical significance of self-focused cognitive processes in SAD, this paper aimed to review theoretical models and empirical evidence for these processes, including limitations of current research, suggested future directions, and clinical applications. While SFA has been the subject of two previous reviews (Bögels & Mansell, Reference Bögels and Mansell2004; Spurr & Stopa, Reference Spurr and Stopa2002), a considerable body of research has been subsequently published, and the current review sought to update this important field. Furthermore, neither review addressed the role of AR or PER. Hence, the current paper aimed to review evidence for self-focused cognitive processes before and after, as well as during social situations, and to explore the relationship between these processes. Importantly, the current paper endeavoured to explore the clinical applications of these findings to support clinicians in providing the most effective treatment to ameliorate the negative impact of self-focused cognitive processes in SAD.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted among articles indexed in PsycInfo, Medline, and PubMed databases. The keywords employed included: social anxiety, SAD, social phobia, self-focus, attention, self-focused attention, anticipatory rumination, anticipatory processing, post-event rumination, post-event processing, theory, intervention, treatment, and attention training. Reference lists of relevant articles were also closely examined for additional papers.

Theoretical Understanding of Self-Focused Cognitive Processes in Social Anxiety

Self-Focused Attention

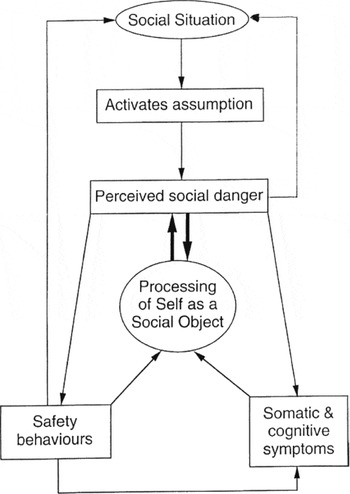

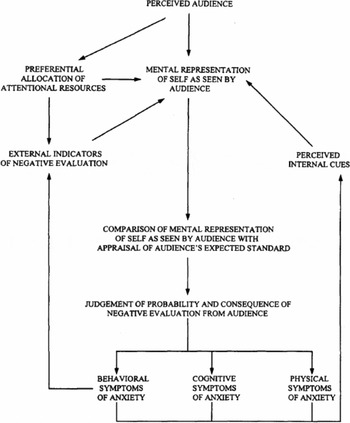

Self-focused attention (SFA) involves awareness of self-referent information, which may present as body state information, thoughts, emotions, beliefs, attitudes, or memories (Ingram, Reference Ingram1990). SFA among socially anxious individuals involves heightened attention toward internal stimuli (e.g., physiological arousal, emotions, cognitions, imagery) during a social or performance situation (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). Thus, Clark and Wells (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) describe that when socially anxious individuals believe they are in danger of negative evaluation they shift their attention to a process of detailed, self-focused observation, and this increases awareness of self-relevant thoughts, feelings, and internal sensations. This process is intended to facilitate self-preservation by enabling the avoidance of social threat. Once an individual is self-focused, internally generated information is used to construct a mental representation of the individual's appearance and behaviour from an observer perspective (as presumably seen by their audience). This impression of the self is focused on the features of the external self, which may be associated with an increased risk of negative evaluation, and is constructed based on somatic anxiety symptoms (e.g., increased heart rate, sweating, feeling flushed), as well as anxious feelings and cognitions about their social performance (Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). The mental representation of the self typically incorporates negative images and perceptions of the self in the current social situation, as well as distorted memories of the self in other situations. Rapee and Heimberg (Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997) similarly emphasise the role of SFA in maintaining social anxiety, but suggest that socially anxious individuals are simultaneously vigilant to external sources of threat (negative evaluation), such that these attentional processes interact.

FIGURE 1 Clark's (Reference Clark, Crozier and Alden2001) cognitive model of social anxiety disorder (adapted from Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995). Note: Printed with permission from the publisher, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

FIGURE 2 Rapee and Heimberg's (Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997) model of social anxiety. Note: Printed with permission from the publisher, Elsevier Science Ltd.

SFA and the use of the observer perspective during social and performance situations is hypothesised to maintain social anxiety in several ways (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). First, SFA exacerbates anxiety by increasing the salience of negative interoceptive information, thoughts, feelings, and self-impressions, leading the individual to sense s/he is being perceived negatively. This occurs at the expense of external information about the social situation, interfering with processing of the audience's behaviour and generating negative biases in the individual's social judgments. Thus, the possibility of noticing positive or neutral feedback is reduced, preventing disconfirmation of fears from external information. Moreover, since the elements used to build the impression of the self are symptoms of anxiety, fears of appearing ineffectual or flawed are likely to be confirmed. Taking the observer perspective in constructed self-impressions may further reinforce the individual's belief in the image, as the external viewpoint provides additional credibility. Furthermore, assuming one's own evaluations are also held by others exacerbates the experience of social anxiety. Finally, lack of outward directed attention may further compromise social performance, thereby making feared consequences more likely to occur (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2007; Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). Thus, attentional processes are thought to maintain social anxiety by increasing in-situ anxiety and preventing individuals from disconfirming their maladaptive beliefs.

Anticipatory Rumination

Self-focused cognition is also theorised to be evident in socially anxious individuals prior to a social situation. Anticipatory rumination (AR) is described by Clark and Wells (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) as dwelling in detail on what might happen in an impending social situation, resulting in biased thinking, as well as influencing anxiety and mood. This ‘pre-mortem’ leads to heightened anxiety, increased recall of past social failures, and the generation of negative images of one's self in the upcoming situation (based on internal sources of information; e.g., thoughts, feelings, and somatic sensations). This distorted self-image is used to predict how poorly the individual thinks they will perform and how likely they are to be rejected (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995). Clark and Wells (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) describe that when socially anxious individuals enter a feared social situation they are ‘likely to already be in a self-focused processing mode, to expect outcomes (e.g., physical symptoms) that indicate perceived failure, and to be less likely to notice any signs of being accepted by other people’ (p. 74). Consequently, AR is thought to contribute to SAD individuals’ in-situ SFA, negative experience of social interaction, poorer social performance, and avoidance behaviours.

Post-Event Rumination

Clark and Wells (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) also suggest that processing of the self and performance continues after the conclusion of a social encounter. Post-event rumination (PER) involves a ‘post-mortem’ in which individuals repetitively dwell on their performance following a social situation (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Rachman, Grüter-Andrew, & Shafran, Reference Rachman, Grüter-Andrew and Shafran2000; Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). This review involves reflecting and focusing on anxiety and experience of negative self-perception (actual or perceived inadequacies, mistakes, and imperfections) that occurred during the event, as well as past instances of social failure. Thus, mental representations during PER typically amalgamate negative images/perceptions of the self in the social situation and memories of the self in other social situations (Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). Moreover, cognitive models suggest that socially anxious individuals selectively attend to negative information about themselves and others during the social situation, subsequently brooding over this negative material, and further distorting or reconstructing the memory over time to fit with their negative self-image (Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). Consequently, the person comes to perceive the interaction as more negative than it actually was and concludes that the interaction was another social failure, thereby strengthening beliefs about their social inadequacy. Hence, PER is proposed to contribute to the maintenance of social anxiety by serving as an intermediate process between an individual's initial interpretations and later recall, thereby fuelling anticipatory anxiety and negative affect, and reinforcing negative beliefs of one's social ability (Brozovich & Heimberg, Reference Brozovich and Heimberg2008; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2007).

The Relationship Between AR, SFA, and PER

While self-focused cognitive processes are often discussed and investigated independently, it is important to emphasise that they do not operate in isolation. Indeed, cognitive models of social anxiety imply that these processes are interdependent, interacting with one another (and other cognitive processes) in the form of a positive feedback loop. Thus, PER is hypothesised to increase anticipatory anxiety, reactivate negative self-expectations during AR, and contribute to SFA during the situation or avoidance of future social events (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995). Moreover, SFA during a social situation is believed to distort PER by enhancing memory for negative information. Hence, self-focused cognitive processes that occur prior to, during and following a social event generate a cycle of dysfunctional thinking that contributes to the maintenance of social anxiety (Gaydukevych & Kocovski, Reference Gaydukevych and Kocovski2012).

Empirical Evidence for Self-Focused Cognitive Processes in Social Anxiety

A growing body of evidence supports the role of self-focused cognitive processes in generating and maintaining social anxiety.

Self-Focused Attention

There is considerable support for the role of SFA in the maintenance of SAD, as described by cognitive models (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997). First, many studies have found a strong relationship between social anxiety and trait SFA (see Bögels & Mansell, Reference Bögels and Mansell2004, for a review). Research has consistently and convincingly demonstrated that clinically and non-clincially socially anxious adults display higher SFA in social situations relative to controls and compared to other phobias (see Bögels & Mansell, Reference Bögels and Mansell2004; Hope, Gansler, & Heimberg, Reference Hope, Gansler and Heimberg1989; Spurr & Stopa, Reference Spurr and Stopa2002 for reviews), and that these processes also occur among adolescents (Hodson, McManus, Clark, & Doll, Reference Hodson, McManus, Clark and Doll2008; Ranta, Tuomisto, Kaltiala-Heino, Rantanen, & Marrunen, Reference Ranta, Tuomisto, Kaltiala-Heino, Rantanen and Marrunen2014) and children (Higa & Daleiden, Reference Higa and Daleiden2008; Kley, Tuschen-Caffier, & Heinrichs, Reference Kley, Tuschen-Caffier and Heinrichs2011).

Second, studies examining neural substrates, physiological symptomatology and cognitive processes provide robust support for SFA triggered by social threat and associated negative outcomes among socially anxious individuals (Schultz & Heimberg, Reference Schultz and Heimberg2008). Thus, increased SFA among socially anxious individuals has been correlated with hyperactivation of neural structures related to introspective and self-referential processes, as well as the processing of bodily sensations (Boehme, Miltner, & Staube, Reference Boehme, Miltner and Staube2015). Moreover, under social/evaluative conditions, socially anxious individuals react faster to internal compared to external stimuli (Mansell, Clark, & Ehlers, Reference Mansell, Clark and Ehlers2003), and report predominantly negative and self-focused cognitions (e.g., Beidel, Turner, & Dancu, Reference Beidel, Turner and Dancu1985; Dodge, Hope, Heimberg, & Becker, Reference Dodge, Hope, Heimberg and Becker1988; Heimberg, Bruch, Hope, & Dombeck, Reference Heimberg, Bruch, Hope and Dombeck1990). In addition, SFA among SAD individuals has been associated with higher state anxiety, more biased and negative self-perceptions, and impaired social performance (e.g., Chen, Rapee, & Abbott, Reference Chen, Rapee and Abbott2013; Holzman, Valentiner, & McCraw, Reference Holzman, Valentiner and McCraw2014; Hope & Heimberg, Reference Hope and Heimberg1988; Mahone, Bruch, & Heimberg, Reference Mahone, Bruch and Heimberg1993).

Third, evidence supports the causality of SFA in increasing state anxiety and biased appraisals. This causal relationship has been corroborated by experimentally heightening SFA during social situations and measuring its effect on affective and cognitive processes. A number of studies have demonstrated that inducing SFA via instructions (Woody, Reference Woody1996; Zou, Hudson, & Rapee, Reference Zou, Hudson and Rapee2007), the presence of an audience (Woody & Rodriguez, Reference Woody and Rodriguez2000), the use of mirrors (Bögels, Rijesmus, & de Jong, Reference Bögels, Rijsemus and De Jong2002), video cameras (Burgio, Merluzzi, & Prior, Reference Burgio, Merluzzi and Pryor1986; Kashdan & Roberts, Reference Kashdan and Roberts2004), viewing socially relevant faces (Grisham, King, Makkar, & Felmingham, Reference Grisham, King, Makkar and Felmingham2015), and receiving false physiological feedback indicating an increased heart rate (Makkar & Grisham, Reference Makkar and Grisham2013) increases anxiety and avoidance during a social situation, as well as increasing negative performance appraisals and reducing social self-efficacy (Kashdan & Roberts, Reference Kashdan and Roberts2004).

Fourth, several studies support the contention that negative SFA detracts from external focus on the current social task and prevents socially anxious individuals noticing objective feedback that they could use to update their negative self-impressions and beliefs. After a social situation, socially anxious individuals recall fewer details and therefore have to rely on the biased information they were focused on during the situation (Daly, Vangelisti, & Lawrence, Reference Daly, Vangelisti and Lawrence1989); thus, they are less accurate in their recall (Hope, Heimberg, & Klein, Reference Hope, Heimberg and Klein1990) and tend to construe others’ reactions to them more negatively (Pozo, Carver, Wellens, & Scheier, Reference Pozo, Carver, Wellens and Scheier1991) compared to controls. Conversely, instructing SAD individuals to attend to external information during exposure produces greater reductions in anxiety compared to exposure alone (Wells & Papageorgiou, Reference Wells and Papageorgiou1998).

Fifth, SFA has been associated with negative and biased performance appraisal. Discrepancies between self and observer ratings of performance suggest that socially anxious individuals underestimate their performance and have a distorted representation of how they appear to others (e.g., Abbott & Rapee, Reference Abbott and Rapee2004; Mellings & Alden, Reference Mellings and Alden2000; Norton & Hope, Reference Norton and Hope2001). Indeed, Mellings and Alden (Reference Mellings and Alden2000) demonstrated that socially anxious participants focused more attention on themselves than their partners during a social interaction and displayed larger negative biases in their self-related judgments compared to controls. These findings are corroborated by demonstrations of impaired attentional control and executive functioning among socially anxious individuals during SFA (Judah, Grant, Mills, & Lechner, Reference Judah, Grant, Mills and Lechner2013), indicating that self-focus may interfere with ability to accurately interpret social feedback.

Sixth, research supports the role of negative self-imagery and the observer perspective in the maintenance of SAD. SAD individuals are also more likely to report spontaneously occurring negative images during anxiety-provoking social situations and to see these images from an observer perspective (Hackmann, Clark, & McManus, Reference Hackmann, Clark and McManus2000; Hackmann, Surawy, & Clark, Reference Hackmann, Surawy and Clark1998). Moreover, the tendency of socially anxious individuals to recall social situations from an observer perspective (rather than field perspective — that is, as if looking out through one's own eyes) appears to be specific to situations of high social threat, and becomes more pronounced over time (Coles, Turk, & Heimberg, Reference Coles, Turk and Heimberg2002; Coles, Turk, Heimberg, & Fresco, Reference Coles, Turk, Heimberg and Fresco2001). Indeed, Spurr and Stopa (Reference Spurr and Stopa2003) found that purposefully engaging in an observer perspective (rather than a field perspective) during a social situation resulted in more frequent negative cognitions, more safety behaviours, and worse subjective self-evaluation of performance. Holding negative self-images in mind during a social situation has also been shown to generate greater anxiety, stronger beliefs that one's anxiety symptoms are visible, and reduced ratings of subjective performance (Hirsch, Clark, Mathews, & Willams, Reference Hirsch, Clark, Mathews and Williams2003).

Finally, in considering empirical support for the role of SFA, it is important to note that Rapee and Heimberg (Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997) proposed that SAD individuals focus simultaneously on internal and external cues of threat in social situations, and that these processes are interdependent. They argue that vigilence to external threat informs and increases focus on the internal representation of self, forming a feedback loop that increases state anxiety and maintains SAD. Moreover, the simultaneous allocation of resources to monitoring internal and external stimuli, as well as the task at hand, is considered to impede social performance and may elicit genuine negative evaluation (Heimberg, Bozovich, & Rapee, Reference Heimberg, Bozovich, Rapee, Hofmann and DiBartolo2010). Rapee and Heimberg's (Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997) model contrasts with the view of Clark and Wells (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) that internal self-focus is most signficant in the maintainance of SAD. Thus, Schultz and Heimberg (Reference Schultz and Heimberg2008) reviewed evidence for both models, reporting considerable empirical support for the contention that SAD individuals allocate attentional resources to external as well as internal sources of threat. However, the authors note that the findings of most studies (e.g., Mansell, Clark, & Ehlers, Reference Mansell, Clark and Ehlers2003; Pineles & Mineka, Reference Pineles and Mineka2005) cannot rule out Clark and Wells’ (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) assertion that SAD individuals may be initially vigilent to external stimuli, but quickly divert their attention away from external sources of social threat (e.g., frowning or bored faces) and almost exclusively focus on internal sources of threat (e.g., somatic symptoms, negative self-imagery). Thus, the impact of external focus of attention on SFA remains unclear, and clarifying the role of focusing on external cues is likely to be important for understanding the maintenance of SAD (Schultz & Heimberg, Reference Schultz and Heimberg2008).

Nonetheless, the above reviewed studies collectively support cognitive models of SFA in social anxiety, with substantial evidence linking SFA with increased social anxiety, more negative self-judgments, and poorer perception of social performance. The literature indicates that self-focusing in socially anxious individuals increases anxiety by enhancing the processing of self-relevant information, and maintains anxiety via negative interpretive and memory biases that prevent disconfirmation of maladaptive beliefs. Furthermore, reductions in SFA have demonstrated benefits for ameliorating SAD symptomatology. Reductions in SFA during cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for SAD have been found to predict reductions in social anxiety and belief in feared outcomes (Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Chen, Watanabe, Nakano, Ietsugu, Ogawa, Funayama and Noda2009; Schreiber, Heimlich, Schweitzer, & Stangier, Reference Schreiber, Heimlich, Schweitzer and Stangier2015), as well as mediating symptom reduction following both individual and group CBT (Hedman et al., Reference Hedman, Mörtberg, Hesser, Clark, Lekander, Anderson and Ljótsson2013; Mörtberg, Hoffart, Boecking, & Clark, Reference Mörtberg, Hoffart, Boecking and Clark2015).

Anticipatory Rumination in Social Anxiety

Rumination refers to a ‘mode of responding to distress that involves repetitively and passively focusing on symptoms of distress and on the possible causes and consequences of these symptoms’ (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008, p. 400), and is considered a core process in social anxiety (Brozovich & Heimberg, Reference Brozovich and Heimberg2008). Consistent with the extensive evidence regarding the positive relationship between rumination and negative affect (Thomsen, Reference Thomsen2006), research indicates that ruminative cognitive processes may be detrimental in social anxiety. Anticipatory rumination (AR) has only recently become a focus of empirical attention; however, a limited body of research supports cognitive models of AR in social anxiety and suggest that it is a maintaining factor specific to social anxiety (Mills, Grant, Lechner, & Judah, Reference Mills, Grant, Lechner and Judah2014). Correlational studies indicate that high socially anxious individuals engage in more AR prior to social or performance situations compared to low socially anxious individuals (Hinrichsen & Clark, Reference Hinrichsen and Clark2003; Penney & Abbott, Reference Penney and Abbott2015; Vassilopoulos, Reference Vassilopoulos2004, Reference Vassilopoulos2008), and that ruminative thoughts about upcoming social events tend to be recurrent and intrusive, increase anxiety, and interfere with concentration (Vassilopoulos, Reference Vassilopoulos2004). Furthermore, consistent with models of AR, highly socially anxious individuals report that they are more likely to dwell on ways of avoiding/escaping social situations, catastrophise about what might happen in the situation, engage in anticipatory safety behaviours, generate negative self-images from an observer perspective, and produce fewer positive autobiographical memories and more negative-evaluative thoughts compared to low socially anxious individuals (Chiupka, Mosovitch, & Bielak, Reference Chiupka, Mosovitch and Bielak2012; Hinrichsen & Clark, Reference Hinrichsen and Clark2003; Vassilopoulos, Reference Vassilopoulos2008).

Preliminary experimental studies have compared the effects of induced AR compared to distraction prior to a social task. Some studies have demonstrated that relative to distraction, AR led to increased self-reported and physiological measures (skin conductance) of anxiety, more negative thoughts and unhelpful self-images, predictions of more negative appearance in an impending speech, and stronger conditional and high standard beliefs among individuals high in social anxiety (Brown & Stopa, Reference Brown and Stopa2006; Hinrichsen & Clark, Reference Hinrichsen and Clark2003; Mills, Grant, Lechner et al., Reference Mills, Grant, Lechner and Judah2014; Vassilopoulos, Reference Vassilopoulos2005; Wong & Moulds, Reference Wong and Moulds2011). In addition, consistent with Clark & Wells’ (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995) model, AR has been found to increase SFA and focus on somatic information (Mills, Grant, Judah, & White, Reference Mills, Grant, Judah and White2014), as well as indirectly worsening speech performance via increased self-reported anxiety (Wong & Moulds, Reference Wong and Moulds2011). Correspondingly, the degree to which SAD individuals engage in AR is predicted by anticipatory state anxiety, as well as anticipatory performance and threat appraisal (Penney & Abbott, Reference Penney and Abbott2015).

Furthermore, despite the negative consequences of AR, many socially anxious individuals appear to hold positive metacognitive beliefs regarding the benefits of AR (Vassilopoulos, Brouzos, & Moberly, Reference Vassilopoulos, Brouzos and Moberly2015), believing that AR is a constructive way of controlling anxiety and handling forthcoming situations more effectively (Vassilopoulos, Reference Vassilopoulos2004, Reference Vassilopoulos2008). Thus, both low and high socially anxious individuals have reported that memories of past speeches had a helpful influence on speech preparation (Brown & Stopa, Reference Brown and Stopa2006), and some low socially anxious individuals have reported that AR decreased their anxiety (Vassilopoulos, Reference Vassilopoulos2004). However, AR has been found to partially mediate the relationship between positive beliefs about AR and social anxiety symptomatology, suggesting that metacognitive beliefs about AR may play a role in the maintenance of social anxiety (Vassilopoulos et al., Reference Vassilopoulos, Brouzos and Moberly2015).

Post-Event Rumination in Social Anxiety

Post-event rumination (PER) has been more extensively studied than AR, with substantive evidence from correlational and experimental research supporting cognitive models of this process in social anxiety (see Brozovich & Heimberg, Reference Brozovich and Heimberg2008). For example, Rachman et al. (Reference Rachman, Grüter-Andrew and Shafran2000) observed that socially anxious individuals engaged in more PER about unsatisfactory social events, remembered more negative events with greater frequency, and rated these memories as more intrusive. PER was also correlated with tendency to avoid similar potentially negative social situations (Rachman et al., Reference Rachman, Grüter-Andrew and Shafran2000). Moreover, the positive correlation between social anxiety symptomatology and self-reported recall of PER has been replicated by a number of subsequent studies (Fehm, Schneider, & Hoyer, Reference Fehm, Schneider and Hoyer2007; Kocovski, Endler, Rector, & Flett, Reference Kocovski, Endler, Rector and Flett2005; Kocovski & Rector, Reference Kocovski and Rector2007, Reference Kocovski and Rector2008; Lundh & Sperling, Reference Lundh and Sperling2002; Mellings & Alden, Reference Mellings and Alden2000).

The relationship between social anxiety and PER has also been experimentally examined across social interaction and performance tasks among adults and children. Compared to controls, higher levels of PER have been demonstrated in socially anxious adults the day after a social interaction (Dannahy & Stopa, Reference Dannahy and Stopa2007; Mellings & Alden, Reference Mellings and Alden2000) and following an impromptu speech task (Edwards, Rapee, & Franklin, Reference Edwards, Rapee and Franklin2003). These findings have been replicated among SAD adults in the week following a speech task (Abbott & Rapee, Reference Abbott and Rapee2004; Penny & Abbott, Reference Penney and Abbott2015; Perini, Abbott, & Rapee, Reference Perini, Abbott and Rapee2006). Furthermore, clinical and subclinical socially anxious children demonstrate more PER than controls following exposure to a social-evaluative situation, and self-appraisals worsened over time (Schmitz, Kramer, Blechert, & Tuschen-Caffier, Reference Schmitz, Krämer, Blechert and Tuschen-Caffier2010; Schmitz, Krämer, & Tuschen-Caffier, Reference Schmitz, Krämer and Tuschen-Caffier2011). These preliminary findings indicate that PER may have an early onset, and suggest that it is relevant to the maintenance of SAD across the lifespan.

Other aspects of cognitive models of PER are also supported by the literature, with studies suggesting that PER is predicted by, and maintains, negative self-perceptions. Dysfunctional cognitions, biased threat appraisals, and negative self-evaluations have been demonstrated to be key determinants of PER (Gramer, Schild, & Lurz, Reference Gramer, Schild and Lurz2012; Kiko et al., Reference Kiko, Stevens, Mall, Steil, Bohus and Hermann2012; Makkar & Grisham, Reference Makkar and Grisham2011a; Penney & Abbott, Reference Penney and Abbott2015; Perini et al., Reference Perini, Abbott and Rapee2006; Zou & Abbott, Reference Zou and Abbott2012). Moreover, socially anxious individuals report more frequent, intense, and longer PER following negative-evaluative social events compared to guilt- or anger-inducing events (Lundh & Sperling, Reference Lundh and Sperling2002), as well as situations involving social compared to non-social threat (Fehm et al., Reference Fehm, Schneider and Hoyer2007). Frequency of PER has also been shown to predict recall of negative self-related information on an open-ended memory task (Mellings & Alden, Reference Mellings and Alden2000). During PER, socially anxious individuals report thought content that serves to reinforce negative perceptions of performance, including more negative and upward counterfactual thoughts (‘if only’ type thoughts about how the situation could have been different; Kocovski et al., Reference Kocovski, Endler, Rector and Flett2005), and more thoughts concerned with poor presentation (e.g., poor posture; Kocovski, MacKenzie, & Rector, Reference Kocovski, MacKenzie and Rector2011). Furthermore, high socially anxious individuals report more negative self-images associated with higher negative affect and more negative self-related beliefs relative to low socially anxious individuals (Chiupka et al., Reference Chiupka, Mosovitch and Bielak2012). Such use of imagery during PER may be particularly detrimental for socially anxious individuals, with a recent study finding that compared to semantic-PER, PER involving imagery induced more anxiety in anticipation of a speech task, as well as more negatively biased interpretations of ambiguous social situations (Brozovich & Heimberg, Reference Brozovich and Heimberg2013).

Hence, the literature supports theories of PER as a cognitive process that perpetuates social anxiety by maintaining negative impressions of one's self, negative memories of social situations, and negative assumptions of future social events (Brozovich & Heimberg, Reference Brozovich and Heimberg2008). Furthermore, PER appears to have lasting sequelae. SAD individuals who engage in PER maintain negative views of their performance for up to 3 weeks, whereas non-anxious controls demonstrated increased positivity in regard to their performance (Abbott & Rapee, Reference Abbott and Rapee2004). In addition, compared to non-anxious controls, socially anxious individuals with a higher trait tendency to engage in PER evaluate their performance on a social interaction more negatively a week after its occurrence (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2011).

However, positive metacognitive beliefs about the utility of PER have been associated with PER and social anxiety symptomatology, suggesting that SAD individuals may not consider this process to be detrimental, thereby perpetuating their tendency to engage in PER (Fisak & Hammond, Reference Fisak and Hammond2013). Indeed, in contrast with cognitive models of SAD, Wong and colleagues (Reference Wong, McEvoy and Rapee2015) report findings indicating that PER may not be maladaptive, allowing socially anxious individuals to rationalise perceived social failure. Unexpectedly, in a group with high social anxiety and a high number of recent social stressors, those reporting high levels of PER demonstrated no increase in dysfunctional beliefs over the subsequent week, whereas those reporting low levels of PER demonstrated an increase in dysfunctional beliefs (Wong, McEvoy, & Rapee, Reference Wong, McEvoy and Rapee2015). The authors alternatively suggest that this pattern may only occur in non-clinical samples, or that those reporting a low number of thoughts about the past may have been engaging in avoidance and thought suppression, which has been found to increase symptomatology (e.g., Salters-Pedneult, Tull, & Roemer, Reference Salters-Pedneault, Tull and Roemer2004).

Nonetheless, consistent with studies of depressive rumination, some evidence suggests that distraction may attenuate the effects of PER. Blagden and Craske (Reference Blagden and Craske1996) demonstrated that rumination prolonged negative affect following an anxiety induction, whereas distraction significantly reduced anxiety. Moreover, socially anxious individuals report less anxiety, more positive thoughts, and weaker unconditional beliefs (e.g., ‘People will think I'm inferior’) when instructed to distract compared to ruminate following a speech task (Kocovski et al., Reference Kocovski, MacKenzie and Rector2011; Wong & Moulds, Reference Wong and Moulds2009). However, support for the utility of distraction in reducing social anxiety is inconsistent. Cassin and Rector (Reference Cassin and Rector2011) reported that distraction did not reduce distress following PER compared to a control condition. Furthermore, Field and Morgan (Reference Field and Morgan2004) found that socially anxious participants recalled more negative and shameful memories regardless of whether they were instructed to ruminate or distract. These findings are consistent with Watkins and Teasdale's (Reference Watkins and Teasdale2004) proposition that deliberately redirecting attention away from negative thoughts and feelings by focusing on non-self-related information may not be an optimal strategy for dealing with negative affective states (anxiety or depression). Watkins and Teasdale (Reference Watkins and Teasdale2004) contend that distraction is a resource-intensive process, and may also reinforce unhelpful cognitive patterns that paradoxically increase negative affect (e.g., thought suppression, Fehm & Margraf, Reference Fehm and Margraf2002; and experiential avoidance, Hayes, Wilson, Strosahl, Gifford, & Follette, Reference Hayes, Wilson, Strosahl, Gifford and Follette1996). Moreover, focusing attention away from negative thoughts and feelings impedes the development of self-insight or accurate cognitive representations of one's experiences (Watkins & Teasdale, Reference Watkins and Teasdale2004).

The Relationship Between AR, SFA, and PER

While cognitive models of social anxiety imply that these self-focused cognitive processes are interdependent, very few studies to date have examined the relationship between these processes, and all have focused on the impact of SFA on PER. Preliminary findings suggest that SFA on a negative self-image (compared to a neutral self-image) during a social encounter predicts more negative and less positive PER (Makkar & Grisham, Reference Makkar and Grisham2011b) and that inducing high SFA leads to more frequent PER in the following 24 hours (Gaydukevych & Kocovski, Reference Gaydukevych and Kocovski2012). Likewise, structural equation modelling suggests that PER is partially predicted by the degree to which in-vivo SFA is focused on a negative self-image (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Rapee and Abbott2013).

Limitations in Prior Research

As demonstrated, empirical studies predominantly support self-focused cognitive processes of SAD and suggest that SFA, AR, and PER play a significant role in the maintenance of the disorder. However, there are a number of methodological limitations in the literature to date. Importantly, many experimental studies fail to include an adequately assessed clinical SAD sample. A number of experimental studies have utilised self-report measures, such as the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clark, Reference Mattick and Clarke1998; e.g., Brozovich & Heimberg, Reference Brozovich and Heimberg2013; Judah et al., Reference Judah, Grant, Mills and Lechner2013; Kashdan & Roberts, Reference Kashdan and Roberts2004), the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN; Connor et al., Reference Connor, Davidson, Churchill, Sherwood, Foa and Weisler2000; e.g., Chiupka et al., Reference Chiupka, Mosovitch and Bielak2012), or the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (BFNE; Leary, Reference Leary1983; e.g., Brown & Stopa, Reference Brown and Stopa2006; Grisham et al., Reference Grisham, King, Makkar and Felmingham2015; Makkar & Grisham, Reference Makkar and Grisham2013) to create analogue high and low social anxiety groups. While researchers believe that social anxiety exists on a continuum and social fears may cause functional impairment in individuals who do not meet full criteria for SAD (Stopa & Clark, Reference Stopa and Clark2001), caution must be taken in the application of these findings to clinical populations. While a number of experimental studies have utilised appropriately assessed SAD samples in the study of SFA (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Rapee and Abbott2013; Woody & Rodriguez, Reference Woody and Rodriguez2000) and PER (e.g., Abbott & Rapee, Reference Abbott and Rapee2004; Zou & Abbott, Reference Zou and Abbott2012), only one study to date has investigated AR in a clinical sample (Penney & Abbott, Reference Penney and Abbott2015).

In addition, there is considerable variation in the methodology utilised to elicit state social anxiety across studies. Studies with strong ecological validity have employed a current social task, such as a speech (e.g., Makkar & Grisham, Reference Makkar and Grisham2013; Perini et al., 2012) or interaction (e.g., Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Chen, Watanabe, Nakano, Ietsugu, Ogawa, Funayama and Noda2009; Zou & Abbott, Reference Zou and Abbott2012), allowing for assessment of state affect and cognitive processes. However, other studies have assessed participants in a non-anxious state (e.g., Fisak & Hammond, Reference Fisak and Hammond2013; Vassilopoulos et al., Reference Vassilopoulos, Brouzos and Moberly2015) or have asked participants to recall past social failures (e.g., Cassin & Rector, Reference Cassin and Rector2011; Rachman et al., Reference Rachman, Grüter-Andrew and Shafran2000; Wong et al., Reference Wong, McEvoy and Rapee2015), limiting the application of findings to situations involving current social threat. There is a particular paucity of strong experimental investigation of AR, with only one study of AR to date utilising a state social task (Penney & Abbott, Reference Penney and Abbott2015).

Furthermore, while cognitive models of SAD postulate that self-focused cognitive processes are interdependent, there is almost no empirical evidence demonstrating that relationships exist among SFA, AR, and PER. Moreover, if these processes are connected, the nature of such relationships is poorly understood. All studies to date have focused on the impact of SFA on PER, and there is no empirical evidence demonstrating the possible impact of PER on AR, and AR on SFA. In addition, a small number of studies have begun to explore the neural underpinnings of SFA (Boehme et al., Reference Boehme, Miltner and Staube2015; Judah et al., Reference Judah, Grant, Mills and Lechner2013); however, these findings are preliminary, and no studies to date have explored the neural correlates of AR and PER. Finally, the role of external focus of attention in the maintenance of SAD and its interaction with internal cognitive processes remains unclear. This is likely to be important to understanding the maintenance of SAD, and increasing the efficacy of interventions for the disorder.

Summary and Future Research

The current review has provided empirical support for the role of self-focused cognitive processes (SFA, AR, PER) in maintaining SAD, as proposed by cognitive models of the disorder. There is a substantial body of evidence demonstrating that socially anxious individuals engage in self-focused cognition during (SFA) and following (PER) a social or performance situation, and a smaller but growing body of literature suggesting that a similar process occurs prior (AR) to such situations. Furthermore, the vast majority of research to date indicates that self-focused cognitive processes are maladaptive, and maintain SAD in a variety of ways. However, there remains considerable scope for future research to further investigate the role of SFA, AR, and PER in the maintenance of SAD, and the development of efficacious interventions designed to ameliorate their negative effects.

Future research is required to address the methodological limitations in the field, including use of adequately assessed clinical SAD samples and ecologically valid social tasks, especially regarding AR. Research is needed to experimentally explore the relationships between SFA, AR and PER, as well as mediators of the relationship between SAD and these self-focused cognitive processes. Furthermore, the interaction between internal and external attentional focus requires direct investigation to test the predictions of the two key models of SAD (Clark & Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier1995; Rapee & Heimberg, Reference Rapee and Heimberg1997) with respect to the role of external attentional focus. Moreover, further studies are needed that utilise measures beyond self-report, including physiological arousal (e.g., Grisham et al., Reference Grisham, King, Makkar and Felmingham2015) and eye-tracking (e.g., Judah et al., Reference Judah, Grant, Mills and Lechner2013), as well as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to further investigate the neurological underpinning of self-focused cognitive processes in SAD. Additional research investigating these processes among socially anxious children and adolescents would also be valuable, allowing for greater understanding of the development of self-focused cognitive processes across the lifespan. While there is preliminary evidence supporting the role of SFA (Higa & Daleiden, Reference Higa and Daleiden2008; Hodson et al., Reference Hodson, McManus, Clark and Doll2008; Kley et al., Reference Kley, Tuschen-Caffier and Heinrichs2011; Ranta et al., Reference Ranta, Tuomisto, Kaltiala-Heino, Rantanen and Marrunen2014) and PER (Schmitz et al., Reference Schmitz, Krämer, Blechert and Tuschen-Caffier2010; Schmitz et al., Reference Schmitz, Krämer and Tuschen-Caffier2011) in socially anxious young people, no studies to date have investigated AR, and most research has employed analogue samples. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether the self-focused cognitive processes found among SAD individuals are transdiagnostic (e.g., Schmitz et al., Reference Schmitz, Krämer and Tuschen-Caffier2011; McEvoy, Mahoney, & Moulds, Reference McEvoy, Mahoney and Moulds2010; Rood, Roelofs, Bögels, & Alloy, Reference Rood, Roelofs, Bögels and Alloy2010) or specific to SAD and social threat (e.g., Abbott & Rapee, Reference Abbott and Rapee2004; Fehm, Schneider, & Hoyer, Reference Fehm, Schneider and Hoyer2007; Kocovski & Rector, Reference Kocovski and Rector2007; Wong et al., Reference Wong, McEvoy and Rapee2015), and this issue this is worthy of further investigation. Finally, further exploration of the role of imagery (see Ng, Abbott, & Hunt, Reference Ng, Abbott and Hunt2014) and positive metacognitive beliefs in self-focused cognitive processes (Fisak & Hammond, Reference Fisak and Hammond2013; Vassilopoulos et al., Reference Vassilopoulos, Brouzos and Moberly2015) is warranted, and may provide avenues for improving current treatments for SAD.

Clinical Implications

The findings of the current review have significant implications for the treatment of SAD, suggesting that self-focused cognitive processes should be key targets for the amelioration of symptoms. Indeed, findings among SAD individuals that reductions in SFA mediate symptom reduction in CBT (e.g., Mörtberg et al., Reference Mörtberg, Hoffart, Boecking and Clark2015) and that PER attenuates response to CBT (Price & Anderson, Reference Price and Anderson2011) indicate that these processes should be a central focus of treatment. However, interventions for reducing self-focused cognition among SAD individuals are often embedded within larger trials of CBT. While a small number of studies have attempted to isolate the effect of reducing SFA (e.g., Mörtberg et al., Reference Mörtberg, Hoffart, Boecking and Clark2015; Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Heimlich, Schweitzer and Stangier2015) and PER (e.g., Price & Anderson, Reference Price and Anderson2011), the hybrid nature of CBT generates difficulty in assessing the impact of specific therapeutic components.

Nonetheless, a number of studies have demonstrated benefits of interventions aimed at reducing SFA, including Attention Training (AT; Wells, Reference Wells1990) and Task Concentration Training (TCT; Bogels, Mulkens, & De Jong, Reference Bögels, Mulkens and de Jong1997). These interventions aim to increase flexibility within maladaptive attentional processes by reducing internal self-focus, increasing external or task-focused attention, increasing attentional breadth, and improving ability to shift attention between stimuli (Wells & Papageorgiou, Reference Wells and Papageorgiou1998; Wells, White, & Carter, Reference Wells, White and Carter1997). Several studies have found such training to be efficacious when practised in the context of a hierarchy of socially threatening situations, thus allowing exposure to social situations, as well as to somatic anxiety symptoms experienced in such situations (e.g., Bögels, Reference Bögels2006; Mulkens, Bögels, de Jong, & Louwers, Reference Mulkens, Bögels, de Jong and Louwers2001; Härtling, Klotsche, Heinrich, & Hoyer, Reference Härtling, Klotsche, Heinrich and Hoyer2015). However, Donald, Abbott, and Smith (Reference Donald, Abbott and Smith2014) found AT to be effective independent of direct exposure to social situations, yielding significant reductions in SAD symptomatology as a result of training participants’ ability to focus, strengthen, and shift attention in the context of interoceptive exercises.

Indeed, interoceptive exposure, a behavioural intervention aiming to reduce distress associated with somatic symptoms, has demonstrated transdiagnostic utility in the treatment of a range of disorders, including SAD (Boettcher, Brake, & Barlow, Reference Boettcher, Brake and Barlow2015; Collimore & Asmundson, Reference Collimore and Asmundson2014; Dixon, Kemp, Farrell, Blakey, & Deacon, Reference Dixon, Kemp, Farrell, Blakey and Deacon2015). The use of interoceptive exposure to reduce anxiety sensitivity (distress associated with anxiety symptoms and their perceived consequences) among SAD individuals may diminish the deleterious impact of SFA, thereby interrupting the vicious cycle of anxiety. Specifically, Dixon and colleagues (Reference Dixon, Kemp, Farrell, Blakey and Deacon2015) investigated a range of established and novel interoceptive exercises designed to elicit anxiety symptoms that are especially feared by SAD individuals (blushing, sweating, trembling). The authors report that: (1) blushing was most elicited by placing a heat pack on one's face and consuming hot sauce; (2) sweating was most elicited by placing a heat pack on one's face, running, and doing push-ups; and (3) trembling was most induced by push-ups and weight tasks. Interoceptive exposure exercises designed to optimise corrective learning and reduce idiosyncratically feared anxiety symptoms among SAD individuals may be valuable in disrupting the anxiety escalation typically initiated by SFA. Thus, attention training and interoceptive exposure interventions exhibit considerable promise for enhancing treatment outcomes, and evidence supports their integration into standard treatment protocols for SAD (Boettcher et al., Reference Boettcher, Brake and Barlow2015; McEvoy & Perini, Reference McEvoy and Perini2009).

In addition, cognitive strategies and behavioural experiments aiming to discourage the use of AR and PER have demonstrated utility in the treatment of SAD (e.g., Clark, Reference Clark, Crozier and Alden2001; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Ehlers, McManus, Hackmann, Fennell, Campell and Louis2003; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Ehlers, Hackmann, McManus, Fennell, Grey and Wild2006). However, mindfulness and acceptance-based strategies may also be of benefit in reducing the impact self-focused rumination among SAD individuals, as has been demonstrated for depressive rumination (e.g., van Aalderen, Donders, Peffer, & Spckens, Reference van Aalderen, Donders, Peffer and Spekens2015). It is argued that mindfulness and acceptance-based strategies facilitate a decentred perspective on thoughts and feelings, which are observed as subjective and transient events, rather than necessarily accurate reflections of truth or reality that compel specific behaviours (Bishop et al., Reference Bishop, Lau, Shapiro, Carlson, Anderson, Carmody and Devins2004). This decentred perspective is hypothesised to reduce rumination and automatic reacting to experience, thereby enabling more reflective, flexible responding to situations. Indeed, mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions have yielded significant reductions in symptomatology across treatment studies for SAD, suggesting that they may be a viable intervention for the disorder (see Norton, Abbott, Norberg, & Hunt, Reference Norton, Abbott, Norberg and Hunt2015, for a systematic review). Specifically, studies of SAD individuals have found a brief mindfulness intervention following a public speaking task reduces PER and associated negative affect significantly more than a control condition (Shikatani, Antony, Kuo, & Cassin, Reference Shikatani, Antony, Kuo and Cassin2014), and engaging mindfully with experience during a PER induction reduces distress and increases net positive affect significantly more than a control procedure (Cassin & Rector, Reference Cassin and Rector2011). Hence, the integration of mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions for reducing the impact of rumination before and after social situations among may be a useful avenue of investigation for augmenting the treatment of SAD.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interest

None.