Can the state influence democratic deliberation in grassroots political institutions? This is an important question. Our data allow us to shed some light on this issue because of the matched-pair sampling strategy we outlined in Chapter 1. To reiterate the methodology: we selected adjacent districts on the border of the four modern South India states: the formerly undivided Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. The district border-pairs were chosen partly for the reason that prior to 1956 they belonged to political entities that had lasted continuously for several centuries. In 1956, with the formation of linguistically defined states, new districts were created with the result that the bordering subregions of the old political entity were split between two new states.

The district-pairs were selected because they had several centuries of common administrative history and a common culture influenced by the mix of languages spoken, caste structures, and geography (Rao and Ban Reference Rao and Ban2007; Ban, Jha, and Rao Reference Ban, Jha and Rao2012). They also had similar levels of inequality and land-use patterns (Besley et al. Reference Besley, Leight, Pande and Rao2016). From the matched pairs of districts we sampled villages across modern state borders that share a common majority language. Sociolinguists have argued that such common elements of culture and social structure result in “speech communities” that have common styles of discourse (Morgan Reference Morgan2014). In the South Indian context, David Shulman’s remarkable book Tamil: A Biography (2016) beautifully demonstrates how language and styles of speech are inextricably linked to a sense of identity and community. We can therefore assume that within the old political entities the styles of public debate, the manner interests were communicated in public settings, and the rituals of discursive communication were similar. If styles of discourse differed markedly between gram sabhas in the matched villages sharing an administrative past but now located across state lines, these differences can be attributed to policy changes that occurred after the states were reorganized in 1956. Especially relevant would be differences in states’ approach to implementing the federal directive of decentralized participatory governance.

Using this methodology, we can assess how state policies and practices affect the impact of gram sabhas on the political lives of India’s rural citizens. We focus particularly on how villagers present their interests and demands, express their complaints and concerns, and how effectively they are able to monitor the local state and make it democratically accountable to their needs. We focus as well on how the state conducts itself in relation to rural citizens, paying special attention to what political authorities and state functionaries do to facilitate deliberation. We are interested in how authorities listen, inform, and respond to the actual political participation of rural women and men. We argue that by the way they elicit and facilitate participation, states lay the groundwork for different forms of political performance by citizens.

We have ordered the four (post-1956) states by their panchayats’ democratic institution-building capacity. Although all states were subject to the same federal mandate regarding decentralized participatory rural governance, states differed in the political emphasis placed on the new panchayat system that was supposed to fulfill that mandate. States showed different capacities and willingness to put grassroots governance into practice. These differences can be clearly traced and analyzed in at least four ways: through the history of each state’s engagement with panchayat reform, the degree of financial devolution each allows, the regularity of panchayat elections, and the participatory character of the gram sabha itself. It matters greatly whether gram sabhas were regular, substantive, and predictable affairs or ritualized gatherings devoid of functional and deliberative content. Using these criteria, we categorize the states as low, medium, or high in their capacity for promoting and supporting decentralized participatory governance.

Andhra Pradesh (AP) is classified as low capacity because, at the time our data was collected (and, to some extent, still today), the panchayat system was weak. There was practically no devolution of funds, and village meetings were unpredictable events attended by a handful of villagers who remained largely passive. Panchayati raj institutions’ support of grassroots democracy is largely a function of political will. Being categorized as “low capacity” in this scheme does not indicate a weak state. It indicates a state’s de-emphasis of the decentralized panchayat system in favor of more centralized decision-making. Karnataka (KA) and Tamil Nadu (TN) are classified as “medium capacity” for the following four reasons: their long history of panchayat implementation; their relatively greater devolution of financial powers to village councils compared to AP; a conscientious cadre of panchayat officials who play an active, responsive role in disseminating information; and regularly held gram sabhas, actively attended by villagers.

Kerala (KL) is classified as “high capacity.” In Kerala the grassroots deliberative process was preceded by an important “People’s Campaign,” which created effective systems of participatory planning accompanied by significant devolution of funds and power. Development planning in Kerala consists of a set of nested, cumulative stages. Meetings of villagers at the ward (neighborhood) level lead to the formation of working groups; these, in turn, lead to village-level development “seminars” where village needs are identified and suggestions for development projects are formulated; these culminate with the gram sabha where the lists of suggestions from the working group are announced and taken up for further discussion and ratification.

Kerala’s gram sabhas are structured in a unique way and can vary depending on their timing in the planning cycle. Those gram sabha meetings held at the end of a planning period are focused on facilitating discussions aimed at formulating ward-level needs for the forthcoming planning period. Accordingly, villagers are assigned to thematic groups and each group is tasked with formulating a list of projects based on identifying common needs (this is in addition to the projects suggested by the working groups). Villagers have break-out group discussions at the end of which the collective decisions are read out in the gram sabha. These plans are then taken up for implementation by the working committee. In subsequent gram sabhas, in the new planning period, the groups focus on verifying the eligibility of villagers who apply for government subsidized benefits and rank them by priority. Kerala’s gram sabhas are thereby managed to reach consensus efficiently and productively on their two main functions.

Our transcripts record only the gram sabha proceedings at the gram panchayat level. We are not able to observe the break-out group discussions because several groups simultaneously hold internal discussions to identify needs or rank order benefit applicants. Neither do we observe the lower ward-level meetings where most of the citizen deliberations take place. These are limitations in our data on Kerala. For these reasons the transcript data are replete with lengthy speeches by panchayat officials and bureaucrats and thin on public deliberations. The scarcity of public deliberations in the transcript data should not be read as their complete absence in the actual proceedings. Compared to other states, the process of deliberation was highly rationalized and streamlined.

In our sample we have four matched district pairs in which each district falls across a state line between states that differ in their panchayat system’s effectiveness in promoting grassroots democracy. In most villages we observed a single gram sabha. In a subset of villages we observed a second. (This is why the number of gram sabhas observed exceeds the number of sampled villages.) In order to make the matched comparisons across state lines robust, we have compared gram sabhas in villages with similar literacy levels. However, for the sake of brevity, in presenting our results we have organized the findings by state and not by literacy levels. Table 3.1 lists the district-pairs and the numbers of sampled gram sabhas and villages by literacy level.

Table 3.1: District Pairs Classified by State Capacity for Fostering Decentralized Participatory Governance

| Low | Medium | High |

|---|---|---|

| Chittoor (AP) | Dharmapuri (TN) | |

| 7 gram sabhas from 7 low-literacy villages | 32 gram sabhas from 21 low-literacy villages | |

| 10 gram sabhas from10 medium-literacy villages | 14 gram sabhas from11 medium-literacy villages | |

| Medak (AP) | Bidar (KA) | |

| 18 gram sabhas from 18 low-literacy villages | 11 gram sabhas from 11 low-literacy villages | |

| Coimbatore (TN) | Palakkad (KL) | |

| 20 gram sabhas from 10 high-literacy villages | 18 gram sabhas from 18 high-literacy villages | |

| Dakshin Kanada (KA) | Kasargod (KL) | |

| 16 gram sabhas from 15 high-literacy villages | 16 gram sabhas from 16 high-literacy villages |

[Notes: Low-literacy villages are those where less than 33 percent of the population is literate, minimally defined as being able to sign their name, and high-literacy villages are those where at least 66 percent of the population is literate.]

Summary of Findings

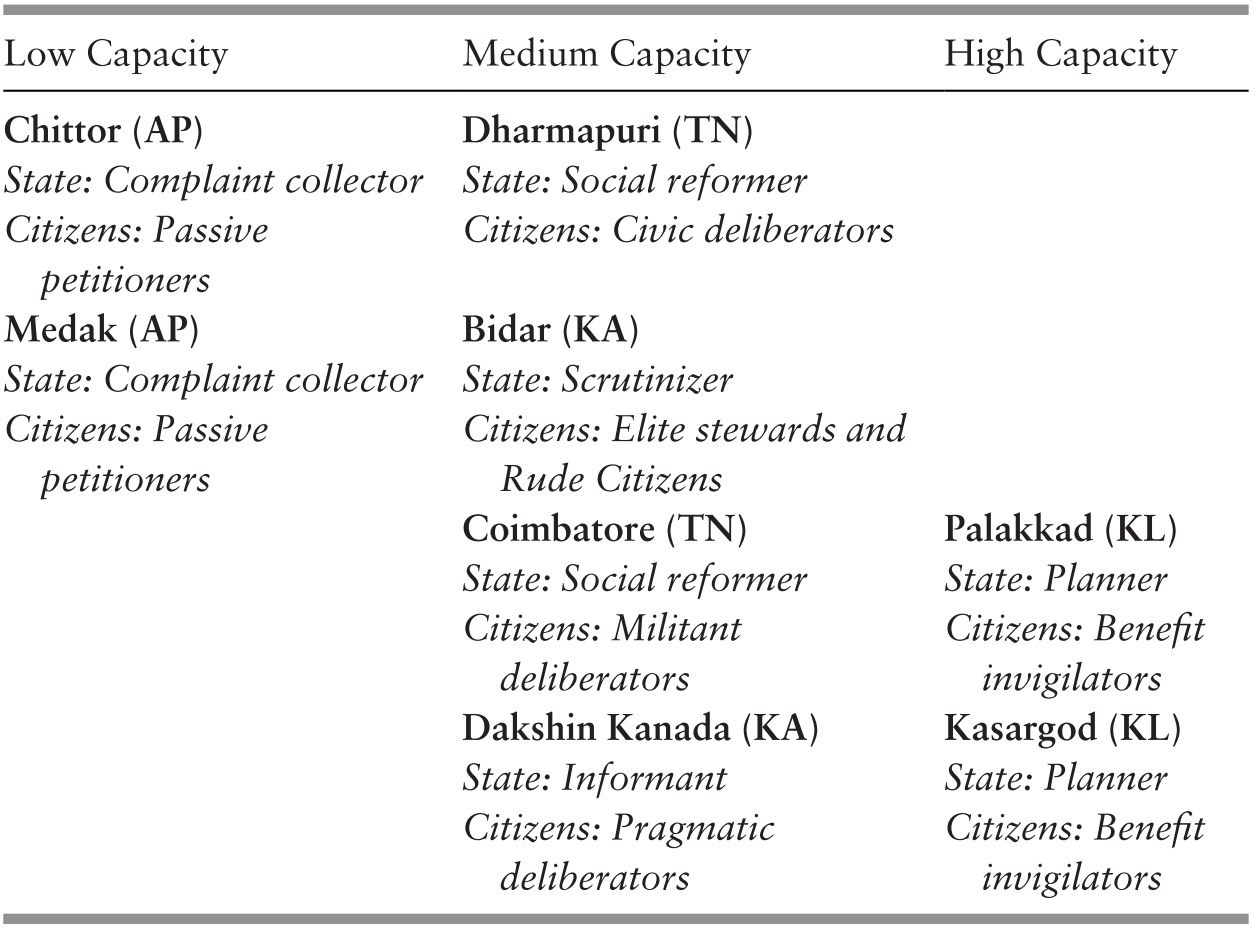

Gram sabhas in matched districts falling across state lines varied greatly in their structure, functioning, and deliberative capacities. While we did expect some subnational variation, we were surprised by the extent of the differences in gram sabhas between states. There were significant differences even though all states are subject to the same federal mandate to foster decentralized governance to further participatory democracy. This chapter gives a detailed look at differences in how the gram sabha is structured. It shows what the agents of the state do in these meetings, and how the state shapes from above the participatory role of villagers at the grassroots.Footnote 1 We focus on identifying and categorizing the different types of state enactments in relation to citizen performances that came to life in the gram sabhas we recorded and observed.

State enactments were embedded in the rituals of governance adopted by panchayat leaders and state officials to facilitate and manage the gram sabhas. Citizens’ performances were analyzed by drawing on how villagers participated as citizens and whether they displayed a heightened awareness of themselves as subjects of a democratic state. How villagers participated was partly circumscribed by routine administrative governance functions they were expected to fulfill at these meetings. It was shaped as well by the scope given to them to deliberate and partly by what they could do using their own savvy to navigate the opportunity of talking to the state. We present in Table 3.2 a typology of state enactments and citizen performances. Our goal is to advance an interpretive understanding of what can often seem to be the quite mundane workings of the gram sabha. Our typology is meant to reveal the meaningfulness of the gram sabha as a grassroots political exercise that has civic ramifications well beyond rural public service delivery.

| Low Capacity | Medium Capacity | High Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Chittor (AP) | Dharmapuri (TN) | |

| State: Complaint collector | State: Social reformer | |

| Citizens: Passive petitioners | Citizens: Civic deliberators | |

| Medak (AP) | Bidar (KA) | |

| State: Complaint collector | State: Scrutinizer | |

| Citizens: Passive petitioners | Citizens: Elite stewards and Rude Citizens | |

| Coimbatore (TN) | Palakkad (KL) | |

| State: Social reformer | State: Planner | |

| Citizens: Militant deliberators | Citizens: Benefit invigilators | |

| Dakshin Kanada (KA) | Kasargod (KL) | |

| State: Informant | State: Planner | |

| Citizens: Pragmatic deliberators | Citizens: Benefit invigilators |

In gram sabhas in Chittoor and Medak in Andhra Pradesh, the state acted as a complaint collector. Panchayat presidents and secretaries acted as go-betweens between citizens and the distant state, recording citizens’ complaints and concerns and promising to convey these up the chain of command. On their part, citizens acted as passive petitioners who remained ignorant of the panchayat’s functioning. Sometimes using reverential language to address the state, citizens were reduced to requesting politely the attention of their superiors.

In gram sabhas in Dharmapuri and Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu, the state acted as a social reformer, forever trying to mobilize the public to act in a desired way. Agents of the state were sanctimonious, righteously and heavy-handedly setting the agenda for village development. They imposed a set of priorities for economic, social, and environmental improvement formulated from above. This prefabricated agenda was used to steer and control gram sabha deliberations. Panchayat officials and state bureaucrats hectored citizens to fulfill preestablished governance goals. In Dharmapuri gram sabhas, villagers acted as civic deliberators. They exhibited skill in public deliberation and were not afraid to question authority figures or to hold them accountable. In Coimbatore gram sabhas, villagers acted as militant deliberators. They were belligerent critics ready and willing to excoriate state officials for inaction and inefficiencies.

In gram sabhas in Bidar, Karnataka, the state acted as a scrutinizer, keeping a watchful eye on how panchayats conducted the village’s financial affairs. In a courtroom-like manner, district-level bureaucrats engaged in detailed public examination of the panchayat’s income and expenses in the presence of gathered villagers, passed judgments on the accuracy of the financial records, and provided counsel regarding proper bookkeeping practices. Public participation in low-literacy Bidar revealed a bipolar pattern. Some villagers acted as elite stewards who played a dominant role in gram sabha deliberations and served as informal coaches in public speaking to other participants. A large contingent of other villagers acted as rude citizens. These citizens were perceived to be creating a commotion and were rudely reprimanded by public officials. In Dakshin Kanada the state acted as an informant, keeping villagers abreast of panchayat and government actions and providing meticulously detailed information on budgets and development projects. Villagers who were knowledgeable and articulate acted as pragmatic deliberators. Their discursive style was constructed and tailored to arrive at efficient decision-making.

In gram sabhas in Palakkad and Kasargod in Kerala the limitations of our data should be kept in mind. We only observe one part of a nested deliberative process. It is clear that the state acted as a planner by rationalizing and streamlining the process of public deliberation and development planning. State representatives frequently sermonized the villagers on civic conduct and ethics. Citizens, for the most part, were turned into benefit invigilators by being made responsible for examining the authenticity and accuracy of applications for a plethora of government-subsidized benefits and tasked with priority ranking applicants following a rigorous point allocation system.

A state’s governance strategies, we conclude, can significantly influence citizens’ civic capabilities, including their capacity for discursive (through talk) civic engagement. This attribute of state governance will become increasingly important as deliberation-based decision-making is embraced across institutions.

PAIR 1. CHITTOOR, Andhra Pradesh (low capacity) – DHARMAPURI, Tamil Nadu (medium capacity)

Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh: Gram Sabhas in Low- and Medium-Literacy Villages

Historically Chittoor had low levels of feudalism. It was part of British India and was largely under the ryotwari system, where the state collected revenue directly from the cultivator instead of having a class of mediating landlords. Despite the lack of feudal influences, at the time of data collection in 2002–2004, the panchayat system was immature. For various political reasons, the state until then had deemphasized the panchayat system. Gram sabhas in low- and medium-literacy villages were broadly similar in their structure and functioning. The length of a gram sabha meeting ranged from fifteen minutes to a maximum of an hour. A paltry number of villagers and very few panchayat and government officials attended these meetings. The meetings that were attended by unusually large numbers had specific reasons behind the turnout, like the presence of an MLAFootnote 2 or the distribution of “rice tokens” as a drought relief measure. The few meetings where some information about budget or public works was shared were likely the result of the particular subdistrict involved and not due to the gram sabha itself.Footnote 3 These exceptions aside, the meetings in low- and medium-literacy villages were brief. They started and ended abruptly. They focused on collecting villagers’ demands and grievances. The state, embodied by the gram panchayat head, acted as an agency for complaint collection. After bidding villagers voice their needs, they made perfunctory gestures of recording them.

The following excerpt from a typical complaint collector state illustrates villagers airing their demands and grievances in brief utterances without providing specific, actionable details. The role of the panchayat head is largely ceremonial. In this case, the sarpanch ends the meeting abruptly, as soon as a villager raises the thorny issue of corruption in the distribution of ration cards, which give families access to government-subsidized food grains and cooking oil. The villagers accept the decision to end the meeting without protest.

President: Today on 14th April we have assembled here to conduct the gram sabha. You can state your problems.

Villager [OBC]: There are no roads.

Villager [OBC]: Roads are to be laid.

Villager [OBC]: We have no house.

Villager [OBC]: No bus facility.

Villager [OBC]: People who have no houses need them.

Villager [OBC, female]: We have lots of problems.

President: You tell your problems.

Villager [OBC, female]: We have severe water problem.

Villager [OBC]: We have no bores [ground water wells]; no [water] pumps.

Villager [OBC]: Water is a very big problem.

Villager [OBC]: The bore is not able to supply free flow of water.

Villager [OBC]: Roads are not proper.

President: What else?

Villager [OBC]: There is no bus facility.

Villager [OBC]: We have been saying this everywhere, but there is no use no matter where we complain!

President: What else?

…

President: Funds released by the government are not sufficient for any work. They have to release funds in large amounts. If they release funds, then there is a chance of laying cement roads and implementing drinking water schemes. The MLA of this constituency is providing such facilities to all other villages, but he doesn’t care for this village. We have taken the help of zilla panchayat. To lay the road we have taken Rs. 50,000. We have taken the D.D. for Rs. 2 lakhs and laid the road in Dalitwada [dalit neighborhood]. Panchayat members are not getting any kind of funds or help from the government. They are cutting the funds they have.

Villager [OBC]: They have issued forty-one ration cards for the villages, but some malpractice has been taken place in this regard.

President: I think we can conclude the meeting now.

In another gram sabha, the villagers’ demands were met by the standard cursory response of promises to communicate the problems to higher-up authorities. The following exchanges typify the behavior of the complaint collector state in many gram sabhas:

President: Today we are conducting this gram sabha to discuss the problems in our village and the various activities we have undertaken so far. You can express your problems here.

Villager [youth community member]: There is no proper community hall in this village for holding meetings or events. We should construct a community hall.

President: I will inform the government to construct a community hall and to provide all facilities to conduct meetings. I will try my level best to construct a community hall.

Villager [SC]: There are no cement roads in the village. Cement roads should be laid on all the village streets.

President: Wherever we don’t have the cc roads, I will try and get them constructed at the earliest.

Villager [SC]: There are electricity poles on the streets, but the lights are not there. Should arrange for the lights.

President: I will arrange for streetlights very soon.

Villager [SC]: In the village some people have huts. About fifty families have no houses to stay. So you should construct “pucca” houses for all the house-less people. We have permission to construct houses on the hill but there is no road.

President: I will discuss with the government officials about this problem.

Villager: We don’t have a proper cemetery or graveyard in the village. Sometimes the adjacent villagers throw the dead bodies in the outskirts of our village, and this leads to health problems for our children.

Villager: We have complained to the panchayat office, but till now there is no solution. They are threatening us.

President: I have given a complaint to the collector regarding this but nothing has happened, and I am helpless regarding this issue.

Gram sabhas in Chittoor were empty governance rituals. They were completely devoid of substantive deliberations. There was no dissemination of information on public income and expenditures or reporting on the progress of village public works and ongoing government schemes. This lack of transparency from the government’s side made citizens into passive petitioners, suppliants submissively rehearsing a litany of complaints with little or no effect.

Dharmapuri, Tamil Nadu: Gram Sabhas in Low- and Medium-Literacy Villages

Gram sabhas in low- and medium-literacy villages in Dharmapuri varied greatly from those in Chittoor in three immediately noticeable ways: their duration, the number of villagers attending and participating in discussions, and the number of panchayat officials and district- and block-level government bureaucrats who participated in the meetings. (These included the Block Development Officer (BDO), Assistant Engineer, and Revenue Officer.) The differences attest to the crucial role played by state attention to the panchayat system. The differences in this regard between Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh are exemplary. The gram sabhas in each state differ accordingly. Every single gram sabha in Dharmapuri started with an announcement of the meeting agenda, which included a number of clearly specified topics that were set by the state as governance priorities to be discussed at the meeting. The agenda typically included the following village development priorities: village cleanliness and greening; eradicating child labor and ensuring children’s and women’s development; garbage collection; and rainwater harvesting. There could be as many as ten or twenty agenda items. A substantial part of the discussion was devoted to these themes. The following excerpt records a panchayat clerk announcing the meeting’s agenda:

Mr. Nagaraj [Clerk, OBC]: On 2.10.04, Kondappanayana Palli panchayat meeting is going to be held on behalf of the leader and chief guest. The entire public and other members should come and participate in it without fail.

1. Regarding cleanliness of the village, discussion is to be held and decision has to be taken.

2. Using garbage gathered in the village, worm fertilizer has to be produced. Its advantages should be discussed.

3. Discussion has to be held regarding rainwater harvesting in all places.

4. Private bathroom facilities are to be provided in all houses. Discussion is to be held regarding activating this scheme and maintaining the public ladies’ bathroom. For this they [state government] have given Rs. 500 for constructing toilets in each house. Whoever is interested can apply for it. We give it [money] to you to construct it. We give it through the panchayat.

5. Eradicating child labor and promising that we will not encourage child labor and develop a panchayat in which there is no child labor.

6. Creating awareness.

7. To develop a green panchayat and village, each village has been given one thousand trees to plant. Some have already been planted and now we can plant in other places and even lakes too. Then we can plant all useful plants too.

8. According to the act No. S.S. 495/PWD (e2) dated on 13.1.03, we need to maintain records for all the [water] wells in this panchayat.

9. According to the order of the government, we have to talk about the schemes that are announced by the panchayat.

10. On 02.10.2004, we will observe total cleanliness day.

11. All the plastic garbage and other garbage in all water bodies like lakes, rivers, canals etc. are to be cleared. Decision has to be taken regarding this.

The agenda items are meant to raise public awareness of state-sponsored development schemes and to encourage villagers to adopt them. Panchayat officials report on their implementation and functioning and check villagers’ compliance. This exercise exemplifies the social reformer state. The close integration of state-sponsored schemes into the discursive arena of the gram sabha by government fiat has a striking influence on deliberation practices. It makes the meetings a space where villagers can develop civic consciousness and form broader development aspirations for the village. Even in gram sabhas in low-literacy villages, villagers typically discuss development issues of broad public interest. Public discussion becomes partly an artifact of state policy. A cynical interpretation might argue that the state used the agenda as a tool for monopolizing the discursive space of the gram sabha. However, we see the data as more mixed, reflecting control and manipulation but also the promotion of civic deliberation, sometimes on issues beyond the scope of villagers’ original or immediately pressing concerns.

Public officials made determined efforts to persuade villagers to comply with state-sponsored schemes. They embodied the social reformer state working on the front lines for the benefit of rural communities. In the following excerpt, a Block Development Officer (BDO), an important village-level administrative figure, gives a long speech on sanitation with the aim of persuading villagers to build household toilets. He emphasizes women’s role in the family and appeals to ideals of modernity:

BDO: Now, the main agenda of today’s meeting is to maintain the hygiene and cleanliness of the surroundings. This means that everyone should keep their house and their surroundings clean. If each one keeps their house and surroundings clean, the streets will automatically be clean. But no one does that. So that is why the government has made arrangements for a clean village and that is the subject of today’s meeting – hygienic and clean environment.

What happens if it is unclean? One will fall sick, you will get fever, you will get diarrhea, and you will get all sorts of diseases. Fifteen years back there was no society [referring to women’s groups] or union at all. Now of late, societies and unions have been started, and women play a major role in it now. The key [to the public sanitation facility] is with the women. Men are not even allowed. Now no woman is scared, and they have all the rights … women have progressed to that extent … Only women are responsible persons. That is why there is a saying that if the woman is good then the whole family will be a good family. That is a fact. If a boy studies well it means that the mother is there behind it. To make a person good is in the hands of a woman. You have got such a big responsibility, but you do not bother for the surroundings and for maintaining a clean environment. Say, for example, if you allow waste to accumulate inside or near the house, then we will fall sick, suffer from malaria, and diarrhea. That is why we should not allow flies and mosquitoes to breed near our houses. We can prevent it, and that is why we have to keep our surroundings clean.

Say for your daily [toileting] need you can use the unused land and fields [referring to open defecation]. In villages both men and women do that. But when these lands and fields are no longer there, then what would you all do for your daily need – will it not become difficult? Males can go anywhere, but ladies will face a lot of problems. So, what I say is all of you should have a toilet. In cities there are thousands of houses and each house has a toilet. It is clean. Has the city been spoilt? No. Similarly, if we have a toilet in each and every house here, then our village will also be clean. One who has more money can build a toilet for five thousand rupees. If one is poor, he can make a toilet with a thatched roof, at least – is it not? The town people do not get diarrhea or vomiting. They might fall sick, get flu, fever, and that may be because of water problem. The water may not be good. But not in village, it is not so. So, first think of keeping your village clean, and try to have a toilet in each and every house. Are the females in town only women? Are you all not women? Here, now do you understand?! Only then you will not fall sick, you will not get any disease. We can be clean. Hygiene is the main thing. Have to have a bath daily. We should also teach our children. [Too many voices]

In life there should be some improvement – you have to improve. You do not have to spend more money for that. For each toilet the government is funding Rs. 500. In this village we have built twenty public convenience [latrines] for Rs. 2000. It has been completed, but it is being kept as a memorial. It is not being used. Only if it is used will it serve the purpose, only then the water will flow out of the pit, and water will not stagnate.

If there are ten people in a house, the earth has the capacity to absorb the water used by all the ten people in the house. That is why we are constructing a dry latrine. In the city if we build a septic tank the outlet will have a ditch and the waste will flow out. If dry latrines are built the water is absorbed. There is no harm in it. So each and every house should have a toilet. And please do not use the open barren land that is nearby your homes for your convenience. It will harm you and as well as the surroundings. When the town people are following it, why can’t we do it? In rainy season it is difficult [to go out in the open]; at night time you come back with an insect or worm bite and that also adds to your sickness; and at night time you can’t go outside alone, you have to call someone, say your husband or your neighbor for help, to accompany you as a support so as not to feel scared. Just think of how many hurdles are there. What I say is all practical. I am also a village born and bred person only.

Villagers [many voices]: We are used to this kind of habit and use only.

BDO: What you say is correct. Did we all travel by bus right from the beginning? Did this village have transportation like bus facility twenty years ago? Only now you have that facility. Times are changing; we also have to change accordingly. Earlier we used to go by walking only to the nearby village.

Villager: You say you are giving only Rs. 500.

BDO: We are just aiding you by giving Rs. 500. You have money in your group; you can avail loan and you can build. It is for your purpose and for your hygiene and cleanliness. I am not going to use it. It is mainly for the ladies. Government is helping you by giving you Rs. 500. It will cost you around Rs. 1500 or Rs. 2000. Take loans from your group and build it and you can repay it say Rs. 50 or Rs. 100 per month. The loan will be repaid in about ten months or so, and this becomes a permanent facility for you. The children also can use it. You need not go out in the open; you will not get bad smell; you will not get diseases. Because of this [lack of personal toilet] you will not get a bride for your son from the town side. First question they will ask is, do you have a latrine in your village? He will not ask you, do you have a latrine [for men]? He will ask, is there a bathroom [for women] in your village? Does your village have it?

Villagers [shouting]: We cannot afford.

BDO: What is in this issue of affordability? You have to manage with what you have. Am I asking you to build a huge building or a temple or a tower? This is our basic need – it is most important. Maybe the government will fund this scheme only for another year or so, then they will stop it. First the government will start it, then it will stop – is it not the usual practice? Public should make proper use of it.

Villagers [too many voices]: Now they are giving Rs. 500, then later on they will stop that also?!

BDO: That is what I am saying. You have to improve …

Villagers here act mostly as civic deliberators who by spontaneous choice or design, in agreement or disagreement, speak about civic matters. The simplest response the agenda elicits is a reiteration by villagers of the importance of the issues and the need for villagers to comply. Women and men echo and elaborate on the agenda items. The verbal reaffirmations of the agenda could be cynically interpreted to be a reflection of state indoctrination and rote repetition, though they can also be public commentaries that contain villagers’ critiques and suggestions.

Sometimes, the social reformer state has the adverse effect of sidelining public demands that do not fit the state’s development priorities. For instance, in a particular gram sabha the demand for drainage had been persistently ignored and state officials had suggested digging garbage and manure pits instead. But in this environment of relatively raised civic consciousness, villagers persistently voiced their unmet demands, even when they were not aligned with the state’s agenda. Panchayat heads, whose electoral fate depends on satisfying their constituency, find themselves uncomfortably caught between a state government that had its own set of development priorities and their constituency whose needs were different.

The following excerpt exhibits the contradiction of the social reformer state encouraging school attendance and urging improvement in education but failing to address the lack of roads in some villages. The discussion about the suffering and crisis stemming from the lack of a road ends inconclusively, and the panchayat clerk abruptly transitions to the next item on the agenda:

President [MBC]: On 28.09.2004 the district collector told about the scheme of 70% education for all. We also participated in that. Here the education status is poor. In the places like Pudukadu, Ondikottai, Chengimalaikadu, there are no roads. Children can study up to fifth standard only. For higher studies they have to go to Pongalur or Perumabalum. In Perumabalum the school is in the morning. There is no bus facility for those children. They have to walk. They are not able to walk. There is no road facility in our village. This year nine students have come back [left school]. The reason is that they can’t carry the book bag. We gave petition to the former collector, Ms. Aboorva, and then we gave two petitions to the present collector. And also I gave three petitions to the former collector. But there is no action yet. There is no use. They told many things in the grama sabha meeting. What is the use of conducting grama sabha meetings? The reason is that the agendas made in the grama sabha meeting are not fulfilled. At the beginning many people would attend the grama sabha but nowadays it is getting reduced. The reason is that everyone [state officials] says lies. So there is no use for the people in this grama sabha meeting.

Villager [SC]: We are coming to the grama sabha meeting by walking. About seven or eight women have come to this meeting from Ondikottai by walking. In the previous meeting, that is in the meeting held during the month of October, we told that there is no road facility for us. Our children are suffering a lot. They find it difficult to walk. They are small children, and they are unable to walk with weight [of school bag]. They say they won’t go to school. They say that there is no road, so their legs are aching. Still, we admitted them in the government school. Women are also suffering because of this road problem. We have given many petitions to the collector, and also went directly and gave complaint to the officers about this. We saw all the persons related to this problem. We went to many places and gave the complaint; and we also went to Uthangarai to submit a petition. They said we should make our children study. We can’t do anything. We are not able to walk. [When we were young] We also walked like that on the stones and studied. But our children are not going. We have given petition monthly once directly to the collector. Even now we gave a petition recently. But there is no action yet. The road is as such. We ourselves tried it for rice [food-for-work scheme].

…

Clerk [MBC]: This year nine children have come out [of school] and started grazing cattle … They have to walk 6 kms. There the school starts at 8.30 am. Even if they start here at 5.00 am in the morning, they are unable to reach the school at 8.30 am.

Villager [SC]: They can’t even go by bicycle.

Villager [SC]: Not even by bicycle since the road is in such a [poor] condition. School is in a village with such roads. They say that everyone should study! How can they study? Though we have made many complaints, there is still no action. The collector, VAO, or the Tamil Nadu government, none of them have the will to solve this problem. Our school-going children are suffering a lot. What can we do? Can we vacate this village? Where can we go?

…

Clerk [MBC]: Subject 3: Regarding preparing earthworm fertilizer using the wastage collected in the panchayat. You are putting the waste. If you put it in a pit, then we can produce earthworm fertilizer with that. Now we are going to discuss about that.

In Dharmapuri even though there was a great deal of facilitation of gram sabhas by the state government, there was no discussion of the panchayat budget. This is likely because, at the time in Tamil Nadu, budgetary control lay with the union (block) panchayat, and the gram panchayat had little role in determining financial allotments. But villagers asked about panchayat funds. The resulting interactions were occasions when public officials, who embodied the social reformer state, tried to educate the public in panchayat finance and instill fiscal responsibility in them:

Villager [male]: But the responsibility is with the Leaders. There is a big sewage pond with dirty water lying in the outskirts of the village, which cannot be cleaned by one or two persons. The leaders should allocate funds and should remove it.

Mr. Palanivel [BDO]: There is nothing called fund and all those things. Village panchayat cannot do everything. We are collecting taxes; with that amount how can we spend? When we get married, we should earn money to raise our children. Do you know what are the electricity charges per month? You have to take the responsibility of management of the panchayat. You people do not even allow us to increase the house tax. You people do not pay water tax also. You are asking us to install [light] bulbs in the streets!

The panchayat management is always expecting funds from the government, and they are finding out ways and means to manage its affairs based on these funds. Can we increase the house tax? If you pay Rs. 1 as tax, the government is giving Rs. 1 and 15 paise as funds, together we have Rs. 2.15 paise as funds. We have to operate on behalf of the people. One person said that in the TV room the power supply has been cut. Since you have not paid the money, we have done that. This is only for the usage of people.

Pragmatic discussions of ends and means also take place. For instance, the following excerpt concerns a sustained discussion on the water supply problem that ends with a pair of villagers volunteering financial help and the President agreeing to move ahead with assistance from them. The cooperative discussion leads to a creative solution being proposed:

Villager [speaker 1]: There is no water in the village. What is the panchayat planning to do? There is no water in the tank.

Villager [speaker 2]: Lake should be deepened. This is important. Plumber is not attending to the fault properly.

Villager [speaker 3]: We need an overhead water tank near Thimmarayaswamy temple. People and cattle face much difficulty for water. Ministers and MLA’s have not taken any steps.

Villager [speaker 4]: As much as I know, there is problem of water and electricity supply. Water problems are more severe. There is water connection from Chinnakothur [nearby village]. But somebody has stolen the delivery line since past five years. Now the President has to spend Rs. 2000–3000 to replace the steel pipe connection. Therefore, we request that a pump room with a bore well should be constructed in Bustalapally itself, like the one provided in the public bathroom.

President: I will inform the BDO for necessary action.

… [Other demands are expressed and responded to.]

Villager [speaker 15]: We need public toilet. There is no water in the water tank.

Villager [speaker 16]: There is no water in the lake even, then how can you expect water in the tank.

Villager [speaker 17]: We need cement storage tank at the ground level.

Villager [speaker 18]: If we have water in the overhead tank, then where is the need of smaller ground-level tanks!

President: We can build smaller ground-level tanks only with panchayat funds. But the panchayat does not have sufficient funds.

Villager [speaker 20]: Even if we have water tank, there is no good water, and canal water is not good. We also need drainage. That is what I request the President and vice president to look into.

President: Already all our efforts to build the drainage system could not be carried out because people did not give land, and they themselves directed the drainage water along the roads. Even the drain water pipelines laid were stolen.

…

Villager [speaker 22]: We will be very happy if drinking water facility for us and our cattle is provided by way of water tubs for the cattle and water tank for us.

President: We can do all these things if we get revenue for the panchayat.

Villager [speaker 23]: We are not asking the panchayat to do this. We are asking the government to do this.

Villager [female, speaker 29]: Is it not your responsibility to build the overhead tank?

President: No, it is the water board’s responsibility, and it is asking for commission.

Villager [speaker 30]: Is it 20% [commission]?

President: No, it is 10%. It comes to Rs. 20,000. So I came back.

Villager [speaker 31]: Sir, we two are the temple trustees. We will give Rs. 20,000. You get the sanction.

President: Yes, you also come with me. We will give the money and get the sanction

Gram sabhas in low- and medium-literacy villages in medium-capacity states like Tamil Nadu could be attracting villagers who were relatively educated and well informed, since they perceived the meetings to be effective and substantive exercises. Alternatively, it may be that even illiterate villagers tended to be better informed and capable of effective civic deliberation because the gram sabhas they attended were embedded in state governance structures that actively disseminated information and promoted participation.

Conclusion

There were vast differences between gram sabhas in Chittoor in Andhra Pradesh, and Dharmapuri in Tamil Nadu. In Chittoor, gram sabhas operated largely as spaces where state agents came to record public complaints and demands. There was not a single instance of villagers engaging in oversight of panchayat expenditure, demanding accountability, or monitoring the progress of public works. The state did not supply information about budgets or anything else. No government line department officials attended these meetings. These lacunae reflected the lack of importance with which gram sabhas were treated by the state government. In contrast, in Dharmapuri the state played the social reformer role. It was intent on raising public consciousness about village development issues crafted to align with state priorities. State agents engaged in social and moral persuasion to influence villagers’ preferences to adhere to the state’s development priorities. Public officials adopted a didactic tone in addressing villagers. They fostered as they steered deliberation. This resulted, on the one hand, in inculcating civic consciousness among the citizens, including on topics that were not among the natural priorities of the villagers themselves, such as the greening of the village, hygiene and sanitation, child labor, and rainwater harvesting. On the other hand, it resulted in a crowding out of deliberative space by dictating the topics for deliberation. This control of the deliberative space should not be understood as precluding deliberation. There was a significant degree of deliberation on some of the state designated issues that coincided with the villagers’ priorities. Villagers were also able to bring up topics that were not on the official agenda. The villagers in Dharmapuri were civic deliberators whose participation in gram sabhas reflected an emerging civic consciousness and the capacity for public deliberation.

PAIR 2. MEDAK, Andhra Pradesh (Low Capacity) – BIDAR, Karnataka (Medium Capacity)

Medak, Andhra Pradesh: Gram Sabhas in Low-Literacy Villages

Gram sabhas in Medak operated as complaint recording sessions, and the state acted as a complaint collector. Public participation was limited to brief utterances of demands and grievances, and panchayat officials functioned as intermediary messengers promising to convey grievances to higher authorities. Typically, the panchayat head started the gram sabha by simply commanding villagers to speak. The state in this historically feudal village appeared as a remote institution operating at a great remove from its rural clients. Officials from the government line departments were not present in any of the meetings, and there was never any mention of public works or budgetary allocations. Overall, panchayat officials maintained an attitude of disdainful aloofness throughout this civic exercise. In the following excerpt, the sarpanch responds brusquely to a villager’s complaint:

Villager [female, OBC]: Sir, [to ration inspector, henceforth, RI] you haven’t given me drought rice.

Villager [female]: President knows that. Every time I go to his office he says, “Let’s see.”

RI: The president is present right here.

President [male]: Do you think I carry around the full list of villagers always? What can I do other than saying let’s see!

Female [OBC]: He [sarpanch] did not inform me about it sir.

RI [male]: OK. That quota is completed. We will definitely enroll your name in next quota. Please tell me what do you want us to do for you? Do you want to get pension?

In a second excerpt, in a village where upper caste dominance is prevalent, the upper-caste male panchayat secretary reprimanded a low-caste female panchayat president when she unexpectedly broke her silence and expressed frustration at being persistently sidelined. Caste and gender are both at play here as principles of power used to suppress voice:

President [female, SC]: They [other panchayat officials] don’t pay any heed to the sarpanch because I’m a poor woman. Nobody pays any attention to my words. You do everything by yourselves and keep me aside as I’m from the lower caste.

Secretary [male]: Why do you say we don’t pay you attention? We told you about this meeting. You’re the sarpanch, and everything will be done with your direction. [Addressing the sarpanch’s husband, who is present among the crowd] You should tell your wife [the sarpanch] how to behave in a general meeting like this.

In the typical gram sabha in Medak, villagers voiced a range of problems about village infrastructure and resources, usually addressing panchayat officials in a beseeching manner. Their discursive style relied on describing a problem, lamenting the negligence, and politely requesting attention from higher authorities. When they complained about government inaction, their tone was reverential. Villagers were careful to show deference to authority. They did not demand information on current budgetary allocations nor did they question panchayat officials on the use of past funds. Here again villagers acted as passive petitioners, combining polite complaints and pleading with submissiveness:

President [OC]: Today we have assembled here to discuss the various problems being faced by us. I wish that the elders present here put forth our problems to the government and get something positive done…

…

Villager [male, SC]: There is no linking road to our village. The drainage and water problem persists. I wish at least now the government will look into our problems and do something for our betterment.

Villager [male, SC]: There is a problem of transportation.

Villager [male]: Namaste to all members of the gram panchayat. We have become independent more than fifty years ago, yet we haven’t developed. Whenever a problem was raised, it was only discussed. After Mr. Ashok Deshmukh was elected the president things seem to be better. We have all contributed and purchased a water tanker. We had also staged a protest rally in front of the District collector, Shanti Kumari. Though she has given an assurance, nothing has come out it. No money has been sanctioned to us for this purpose. There is a need for a panchayat building. Then we need roads and drinking water.

Villager [male, SC]: There has been some development. A road has been laid in the SC colony and more needs to be laid.

Villager [male, SC]: No matter how many problems we talk to you about in these grama sabhas, there seems to be no solution. So there is no need to express any problem. There is no development at all.

Villager [male, BC]: There is no hospital in our village. We have to walk 3 kms to reach the hospital. The compounder will not get up. And even if he gets up he writes some prescription.

President [OC]: OK, you expressed your problems; we will note them down and try to do something.

…

Male [SC]: What is the use of writing down? Has the government done anything up to now? We have expressed our problems and said what needs to be done. If there is an assurance along with the time frame it will be good.

Gram sabhas in Medak did not appear to have a role in local governance. State facilitation of these deliberative forums was thoroughly lacking. They did not increase transparency. They were not spaces where state agents fostered villagers’ civic consciousness, capacity for deliberation, or their power to hold public officials accountable.

Bidar, Karnataka: Gram Sabhas in Low-Literacy Villages

In Bidar, gram sabhas were conducted by strictly adhering to an institutional structure laid down by the state. They uniformly started with the public auditing of the panchayat’s accounts, called the “jamabandhi.” The “Nodal officer,” who was a government bureaucrat, conducted the audit and served as a direct link to the resources and power under the government’s command. Due to this institutionalized system of public audit, a lot of budgetary information was brought to light and discussed in the public domain. This practice led government officials to play a significant role in interrogating and coaching panchayat officials about the proper maintenance of financial records and in imposing a sense of public financial accountability. As a result, gram sabhas were highly informative and substantive exercises. A significant part of the long meetings was occupied by meticulous inspection of panchayat accounts and records. In Bidar, we find the scrutinizer state embodied in the supervisory figure of the nodal officer.

The following excerpt showcases a nodal officer explaining the purpose and procedure of the “jamabandhi” before commencing on the time-consuming task. He explains how the practice is intended to promote transparency and cultivate the public’s capacity of performing independent oversight of the panchayat’s workings. The surprising fact is that this particular meeting was attended by only five villagers. This did not discourage the nodal officer from fulfilling his function. This gram sabha meeting went on for five and a half hours. It stands as a powerful example of state facilitation of citizen participation in low-literacy Bidar:

Nodal officer [male]: Dear friends, president of the Gramapanchayat, members, villagers, secretary, and vice-president, according to the higher officials meeting held on 20th, you have received funds under several different schemes like SJRY, Indira Awas Yojana, and Ashraya for the year 2004–05. The president and secretary will arrange for a meeting to check whether all the works are completed or any are pending. This needs to be done in front of all the villagers, and they [villagers] should see the accounts. I will extend a warm welcome to all the people who are here. You will do lot of discussion on the works completed and those pending. The government has instituted this practice to know about all the issues. They have made a law called transparency to keep all the citizens informed about all the works done and to educate them. Whether it be road, drainage, electricity, water, whatever it is, first you should be informed about the grants that have been received and spent, then about the new work to be undertaken. Ward members should also know these things. So we have organized this Jamabandhi program today. I will look into every single issue and comment if they [panchayat officials] don’t produce the needed documents. Nobody should comment on someone else unnecessarily. I will look into all the related applications, make a note of it, and submit to the office. This is the intention of this program.

In your action plan, some details are there and some are missing. Now, we will proceed with whatever details your secretary will give us pertaining to SJRY or water supply, and we will inform you accordingly. If some mistake has been committed and you want to inform us, you should not fight and shout. You should remain calm and cool and inform us about it, and we will check against the records in this book to decide whether the secretary has done it correctly or not. If we find any mistakes, we will let you know, and we will read out whatever we write. All the information will be brought to the notice of the government and gram panchayat members, and it will be set right. It should be transparent. All these days this [transparency mechanism] was not there, now it has come [as a directive from the higher tiers of the government]. I request all of you to cooperate and thank you for the opportunity [claps].

During these highly technical public audit sessions, villagers were mostly spectators. Although they were often unable to grasp the intricacies of accounting, because of the emphasis on public accountability they had imbibed a sense of having some power over panchayat officials. This was reflected through their line of questioning and commentary on the functioning of panchayat officials:

Secretary [male]: It is settled Sir. But they haven’t given the voucher.

Villager [male]: If there’s no voucher, how can you believe that the work has been done? If the work is done then only they can make the payment.

Nodal officer [male]: They have showed it as outstanding in audit. This audit happens once a year. Do one thing – write that it is shown in the outstanding book. The villagers are saying that they have not done the settlement. They should understand.

Villager [male]: Why do you tell us? Will you give any of that money to us? They get the money, and we don’t even get to know how much grants they’ve received? Sir, now you see why they haven’t given a letter? Nobody here takes the responsibility; anything can be done on the basis of mutual understanding and faith.

Nodal officer [male]: They should know that they need to submit it. The people who do the work should ask for it in the general body meeting. Out of six projects, five are listed here. Have these works been completed? What is this pipeline work? It’s not listed in the action plan. OK, is the work at least over?

Secretary [male]: It is over sir.

Nodal officer [male]: Our people can’t understand!

Villager [male]: Drainage work is not complete, sir. You arrange for a meeting tomorrow; let us discuss about it.

Villager [male]: They should answer all these questions, no? Or else, what’s the use of the people coming here. Let them reply!

Nodal officer [male]: This is an open meeting. We’ll discuss everything in front of you. We will take approval from you and proceed. You are the citizens of this village.

Public participation in low-literacy gram sabhas in Bidar was variable both in numbers participating and in the quality of participation. The numbers of villagers attending ranged from one to over one hundred. The meetings also ranged from being orderly to unruly and raucous. In general, at the meetings in Bidar, villagers spoke freely, presented their demands, challenged claims made by panchayat officials, demanded information and clarifications, and proposed new works. In some of them people created a commotion and completely disrupted the meeting.

The meetings were characterized by two distinct patterns of participation. A large proportion of the public operated with comparatively little knowledge about government programs and gram sabha procedures. Many were not adept at public deliberation and were often discourteous in their speech. This type of performance typified what can be called rude citizensFootnote 4 and most likely captures the participation of illiterate and less educated villagers. By contrast, in every meeting there were a handful of villagers who made instructional interventions and tried to coach their illiterate peers in the proper manner of deliberation. These individuals, who were most likely educated, were often the dominant voices in the meetings and displayed experience in deliberation. They typify what we call elite stewards. This polarized pattern of participation can be associated with the skewed distribution of education. In a medium capacity state where gram sabhas were substantive exercises, a largely illiterate population could incentivize the educated minority to attend and be vocal.

A typical gram sabha in Betagery showcases the two discursive patterns. It is a forty-minute-long meeting attended by forty villagers and starts with a deliberative exchange about “check dams.”Footnote 5 Under a government waterworks project, a check dam has been sanctioned for the village. This leads to substantial discussion on whether a check dam is really needed and the suggestion that the funding be used instead for other purposes. The joint engineer rejects the suggestion, and subsequently a villager makes another proposal that is accepted. At the end of this deliberation, the meeting breaks up in raucous confusion. While some villagers earnestly continue the discussion, others talk among themselves, shout, and behave disruptively. This leads to a polarized atmosphere, with elite stewards trying to deliberate while rude citizens make rowdy interjections. Some villagers harshly reprimand the panchayat president, the secretary, and members:

Secretary [male]: One check dam is completed but there is provision for one more.

Villager [male]: Don’t want another check dam.

Joint engineer [JE] [male, SC]: You can’t reject the check dam.

Secretary [male]: There’s pressure to execute the check dam.

Villager [male]: If it is so, let us propose to remove the silt instead of building another check dam.

JE [male, SC]: Removal of silt work will come under SGRY.

Villager [male]: You build check dam in some other village.

JE [male, SC]: One will be built in another village, but we have to build another one here.

Secretary [male]: [Addressing villagers] You select the place.

Villager [male]: You execute the work in whichever place is selected, but it will be useless.

JE [male, SC]: Don’t talk like that; there’ll be much use from the check dam [later clarifying that it will provide a means of conserving excess rainwater during monsoons, in an otherwise arid area]. We’ve constructed so many.

Secretary [male]: The work of removing silt cannot be executed by Zilla panchayath.

JE [male, SC]: We’ll start the work soon, and the earth that’s dug out will be collected on the side.

Villager [male]: We shouldn’t put it on the side.

Villager [male]: You should widen the road with it.

Member: Tell further.

Villager [male]: Both road and water are required.

Secretary [male]: OK, then we will use the earth to widen the roads.

President [male, ST]: Agreed!

…

Villager [male]: People are shouting and not listening properly.

Villager [male]: People give different opinions. If one says something, another will not agree with that.

Villager [male]: What will you do in this village!

Villager [male]: Yes, what they’re [panchayat and government officials] saying is correct. Why will they come? Nothing can be said and nothing can be heard. If all of you keep quiet, they will tell and we can listen …

Villager [male]: Come let us go; we have work. Let us go.

Villager [male]: The water level in the well has decreased.

Villager [male]: If you want to ask, remain here or else go away.

…

Another exchange reveals the villagers’ capacity to demand accountability from public officials, but using harsh language to do so. In the following excerpt, villagers question the quality and quantity of food supplied under the school midday meal program and reproach a schoolteacher for trying to deflect criticism with unrelated arguments. The lack of deference the villagers exhibit is noteworthy. It contrasts markedly with the deference typically shown in Medak:

Villager [male]: The management of the midday meal program in the school is not being done properly. They are not serving proper food to the students. The preparation of food is not up to the mark. It makes the students fall sick and the cooks simply take the food home.

…

Villager [male]: The food is not cooked properly, and the members never look into what is being cooked. Change the cook!

Teacher [male]: My name is Rajasekara; I am the co-teacher. Food will be prepared and served to the students. Some days, there may be some excess food remaining after the meal. The workers will carry the remaining food to their houses, instead of wasting it. In future, we will follow your instructions.

Villager [male]: For how many students is the food prepared?

Teacher [male]: We prepare food at the rate of 100 gms per head, but sometimes there’s a bit of excess and sometimes it falls short. If it falls short then it is adjusted during serving, and if there’s excess then the villagers take it home.

Villager [male]: They’re taking it home every day!

Villager [male]: Since the past three days this is happening.

Villager [male]: Everybody knows it. Even the students know.

Villager [male]: This is the third day.

Teacher [male]: I am a teacher and I’m transferable. This is an internal problem of your village. The cook belongs to your village and has been appointed by all of you. If you discuss the problem in the meeting, it will be solved. The cook does not belong to my place; the error is human. If you find an error on our part, we will surrender and rectify it. If not, you can take action against us.

Villager [male]: They are different types [behave differently] before the panchayat and the public.

Teacher [male]: This problem belongs to your village. Grama sabha means not panchayat level. Let us sit, have discussions before panchayat officer, and then come to a final proposal.

President [male, OBC]: In your position, you have powers to take action against proxy cooks.

Villager [male]: You remove the cooks who are not interested.

Teacher [male]: It is my request to the public and you to tell me clearly that my presence in this village is not wanted by you. Please just say that, and I will go to some other place. As I am a government servant, I can work anywhere. I know what are the topics to be taught to the students, and I am doing it sincerely. But the students return home after school and throw their school bags aside and do other things instead of studying, and the parents are not in a position to guide them properly and direct their studies. So, tell me, how will they become free and fair citizens of India?

Villager [male]: Oh teacher, don’t bluff us!

…

Villager [male]: We should catch hold of the headmaster.

Villager [male]: Change your SDMC [committee] members.

Villager [male]: The existing members’ sons or daughters do not attend this school, so they’re not bothered about attending the meetings. Form a new committee.

Villager [male]: Rice and lentil stocks should be checked often as they become stale quite fast.

…

Villager [male]: They cook the food and this gentleman [the teacher] tries to sell the rice. [mass peaking among villagers]

Villager [male]: You sell to the public and collect money from them!

Villagers also brought allegations that revealed either their failure to grasp, or their unwillingness to accept, some of the requirements on which government schemes are conditioned. For example, some infrastructure schemes had been tied to raising public contributions to match 15 percent of the cost. These matching public contribution requirements had been put in place by the government to create a sense of ownership of public resources among villagers. In the following excerpt, villagers accost panchayat officials and blame them for siphoning off rice received for food-for-work schemes. The secretary explains that the rice was returned because the work had not been properly executed. As this example shows, some complaints voiced in low-literacy contexts have questionable merit. Nonetheless even poor villagers make it clear that panchcyat officials are doing them no favors by attending this meeting and answering their questions:

Villager [male]: Couple of days back rice was received [tied to food for work scheme for people below the poverty line], but it was sent back. Will it be repeated?

Villager [male]: You allot Rs. 1,00,000 for one village, but then you say that we [the gram panchayat, GP] have the grants but you [public] should contribute Rs. 15,000! Who will contribute?

Joint engineer Rajkumar [male, SC]: See, that [type of scheme] has not come now.

Villager [male]: No, not like that. Last time we received rice in panchayath, but it was returned. Why? For what purpose did you spend it?

Secretary [male]: Now we’ve started work on a check-dam and the rice for that is available.

Villager [male]: When did you receive rice? Will you store it in some building and just tell us afterwards that this and that happened with it!

JE [male, SC]: No, no, it never happened like that.

Villager [male]: Simply you will tell, no, work is over, no rice, no rice! And all of you [officials] repeat the same thing.

Villager [male]: Even for the building work rice was received [by the GP]!

Secretary [male]: Yes, even for that, but none of you did the work properly. That is what happened!

Villager [male]: See, you must tell us if earth-work [under food-for-work scheme] is available.

Secretary [male]: The GP members should tell you that.

Villager [male]: You also tell the members [to tell us].

Secretary [male]: That’s why we’re saying all this in front of everyone; the president is here, the members are here, and all of you are present.

Villager [male]: We gave all our votes, no?

This exchange is reminiscent of speech between social superiors and inferiors in the feudal jajmani system that prevailed in the region. What explains why some villagers use such a discourteous tone? One possibility is that villagers realize that panchayat and government officials, who as well-educated members of officialdom are their presumptive social superiors, are now their “servants” who are reliant on them for support. They are required by the state to listen to villagers’ demands and dependent upon their votes for power. This reversal of power may be prompting some villagers to use a tone usually reserved for subordinates.

Conclusion

In Medak (AP) and Bidar (KN) districts, illiteracy exists in conjunction with upper-caste dominance. The social structure of both districts continues to be infused with feudal hierarchies. Historically, Medak and Bidar were part of the erstwhile Hyderabad state. They share a feudal legacy and other cultural and linguistic similarities. The only significant difference between them is that Medak is in Andhra Pradesh (present day Telangana after the division of AP), which neglected to foster the panchayat system, while Bidar is in Karnataka, a frontrunner in implementing decentralized governance. Comparing gram sabhas in Medak and Bidar reveals the difference state facilitation can make in fostering villagers’ capacity to engage discursively with the state and take part in the deliberative process of governance.

In Medak, by not facilitating public deliberation and withholding information related to panchayat activities, the state turned gram sabhas into a vacuous ritualistic exercise. But gram sabhas in low-literacy villages in Bidar, Karnataka, operated very differently. The vast difference in state facilitation resulted in remarkably different patterns of public participation. The meetings started with detailed public scrutiny of panchayat budgets, and this led villagers to be acutely aware of the public accountability of officials. Villagers attending gram sabhas in Bidar were inquisitive and vocal, challenging and confronting. They were never deferential like their counterparts in Medak. Not all villagers were fully informed about governmental regulations or had a full grasp of budgetary information, but they were not shy in demanding information or clarification. A significant part of the meetings turned into question and answer sessions on funds and allocations rather than discussions of ends and means. Often calls for clarification became so boisterous that meetings oscillated between being constructive and cacophonously incoherent. Elite stewards played a prominent role in many of these meetings. Their role was mostly educative and facilitative in making interventions to instruct the villagers on how to frame their demands. Political factionalism was noticed in very few cases. Finally, a number of gram sabhas in Bidar appeared to be highly polarized with verbal conflicts and mass speaking, leading to noisy breakdowns in communication alongside a minority of the attendees trying to engage with the state in a constructive and deliberative manner.

PAIR 3. COIMBATORE, Tamil Nadu (Medium Capacity) – PALAKKAD, Kerala (High Capacity)

Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu: Gram Sabhas in High-Literacy Villages

Gram sabhas in the high-literacy villages of Coimbatore were notable for the information-rich deliberative exchanges between panchayat officials and villagers. The combination of a medium capacity state and relatively high literacy meant that villagers were very well informed about the workings of the local government and knowledgeable about problems relating to public resources and infrastructure. The state here performed as a social reformer state with the same pattern of agenda setting found in Dharmapuri. The villagers were highly articulate and made knowledgeable queries and comments. They had a belligerent discursive style and frequently excoriated panchayat and state officials. Their performance as citizens can be best characterized as that of militant deliberators.

In Coimbatore, as is typical all over Tamil Nadu, gram sabhas start with the announcement of the agenda. The features that stood out were the articulate and informed nature of the complaints by villagers and their demands for accountability on technical details of the execution of public works projects. The complaints and criticisms revealed villagers’ active role in monitoring public works projects. Villagers frequently adopted a combative tone when they demanded accountability, challenged panchayat officials on their claims, and critiqued the perceived ineffectiveness of the gram sabha and the panchayat. Villagers’ critiques were backed up by their knowledge of public resource provision in other villages and relevant technical information. The meetings were both deliberative and confrontational. The following excerpt records a lengthy deliberation in one gram sabha in which the villagers launch a scathing critique of the ineffectiveness of the gram sabha, call the meetings a waste and an “eye wash,” and simultaneously deliberate on multiple issues. These include the nonpayment of house taxes, obtaining water connections, and the problems in the construction of a public lavatory:

Villager: You said there is “drought” and water problem. But the water from the road pipe is getting wasted. It is flowing non-stop on the roads, and you have not done anything to stop that flow and fix the water stagnation. This problem has been there for the past two months. You’re talking about rainwater harvesting! That is not helping the public in any way, where we are not even able to walk on the road during the night. In every gram sabha meeting we have been telling you the things you have not done for Jeevananda nagar. Whoever comes [gets elected] as the head of panchayat, this Jeevananda nagar is neglected, and nobody cares despite us saying that in gram sabha meetings. There is no improvement for the past thirty years. There is no proper road. If there is any emergency, even an auto-rickshaw cannot come here because there is no road at all here.

Villager: So many projects are being announced by the government, but nothing has been done for this Jeevananda nagar. We will feel happy and there will be some meaning in having gram sabha meeting if at least 10% of the projects are carried out for this area. Ever since the panchayat pradhan has been appointed, we have been telling in this meeting, which are the places affected, what are the problems faced by the public, where welfare projects have not been provided. But nothing has been done so far. When you are showing maintenance of drinking water pipeline, you are not sending a plumber to stop that water-flow from the pipe. And then you show electricity expenses, whereas there are no road lights nor are the lights working. You entrust this job to somebody, and he shows some [false] account. Show that he completed the job! Without verifying whether that job has been done or not, you pay them, and show the expenditure in gram sabha. Make sure that at least 10% of the sanctioned projects are implemented, otherwise do not call for such gram sabha meetings at all!

You have laid a road in Kumalapalayam. When water is flowing on the road, what is the use of laying such a road! Where there is water stagnation, the road will get spoiled. There should be some sewerage channel through which the sewage water can pass. You have to check those leaking pipes and set it right, otherwise the tar coating will come off.

Villager: Sir, we are all coming from Chitharasan palayam panchayat. We are about fifty to sixty persons who have come here personally. There is no patta for us, and there is no roads, no road lights, no electricity, no drainage, none of the facilities are there for us. We don’t even have the basic requirement for us. These gram sabha meetings are a total waste! There is no use at all for us to have the gram sabha. This meeting is just an “eye wash.” We have a leader here who does not know anything nor does he know what to ask.

Panchayat clerk: All these things are unfulfilled because there is no fund with the panchayat. We wanted to increase the house tax – what was the tax as per old schemes? It was 0.40 paise per 8 ft, means there will be Rs. 250/- tax per house. You are [living] there for more than forty to fifty years. Out of all of you there are many who have not paid house tax.

Villager: If there are ten welfare projects at least one project should be implemented, then only people will come forward to pay the taxes.

Clerk: Panchayat head emphatically said, if you pay the tax, then only there will be enough fund in the panchayat as well, and matching grants will be received from the government.

Villager: How do you expect us to pay taxes, when we do not have even the basic facility! Do not tell us that shortage of fund is due to non-payment of house taxes. Head has managed to get water from Metthupalayam municipality and able to give piped water to other villages under this panchayat. They have collected Rs. 3000/- per family for pipe connection. When will you give us the connection? Water connection is available for Sudandrapuram, teacher colony, Edyarpalayam. We have already paid house tax, though there was delay. It is more than two months now. What are you going to do about it?