Over the last few decades, childhood obesity has increased dramatically, posing a major public health challenge globally(Reference Lobstein, Jackson-Leach and Moodie1,Reference Pulgarón2) . Overweight and obesity has been identified as a major contributing factor to the development of non-communicable diseases, such as CVD and type 2 diabetes(Reference Pulgarón2,Reference Ogden, Carroll and Kit3) . All these life-threatening conditions pose severe threats not only to individual health but also to the economic wellbeing of wider society(Reference Alleyne, Binagwaho and Haines4,Reference Shetty5) . Unhealthy dietary behaviours have been identified as the leading contributor to overweight and obesity(Reference Forouzanfar, Alexander and Anderson6). Indeed, children’s unhealthy dietary behaviours(Reference Al Ani, Al Subhi and Bose7–Reference Zahra, Ford and Jodrell9) may lead to weight gain and an increased risk of overweight and obesity(10). Most importantly, unhealthy dietary behaviours that develop during childhood and adolescence often continue into adulthood(Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger11). Food environments have been identified as a major contributor to unhealthy dietary patterns(Reference Vandevijvere and Tseng12).

Swinburn et al.(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza13) categorised food environments into physical (what is available?), economic (what are the financial factors?), political (what are the rules?) and sociocultural (what are the attitudes, beliefs, perceptions and values?). Globally, health professionals and policymakers have recognised schools as a potential setting for improving young peoples’ dietary quality through policy implementation(Reference Hawkes, Smith and Jewell14,Reference Jaime and Lock15) . Young people consume over one-third of their daily energy intake at schools(Reference Bell and Swinburn16–Reference Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta18). Therefore, the food environment at schools, including what food schools offer (e.g. via canteen or vending machine), can have a significant impact on children’s dietary behaviours(Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien19). Disappointingly, research indicates that food environments at schools often encourage unhealthy dietary behaviours among students(Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsley20–Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast22). This criticism is mainly attributed to the widespread promotion (e.g. in-school marketing, product placement), availability of and accessibility to unhealthy foods and beverages (e.g. french-fries, chicken nuggets, sugar-sweetened beverages)(Reference Lawlis, Knox and Jamieson23–Reference Vepsäläinen, Mikkilä and Erkkola25) and limited provision of healthy foods (e.g. fruit or vegetable salad) at schools(Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsley20).

On a daily basis, students need to navigate through complex food environments to make food-related decisions that are often automatic or subconscious(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall26). Therefore, it is important to provide a healthy food environment to help students make healthy food choices. A crucial component of the food environment at school is the food and beverage policy(Reference Jaime and Lock15,Reference Swinburn27) that has been implemented in many countries(Reference Jaime and Lock15), for example, the United States(Reference Finkelstein, Hill and Whitaker28), Australia(Reference Lawlis, Knox and Jamieson23) and the United Kingdom(Reference Adamson, Spence and Reed29). Such policies primarily focus on improving students’ food consumption through modifications to the food environment at school(Reference Hawkes, Smith and Jewell14,Reference Lawlis, Knox and Jamieson23) . These policies can include the provision of nutritious food that meet comprehensive and consistent nutrient-based standards, alterations to the presentation of foods at the point-of-sale, and marketing restrictions(Reference Hawkes, Smith and Jewell14,Reference Lawlis, Knox and Jamieson23,Reference Finkelstein, Hill and Whitaker28) . Objective audits, however, suggest that many schools fail to implement or adhere to healthy food and beverage policy standards(Reference Fletcher, Jamal and Fitzgerald-Yau30,Reference Kim31) . This failure highlights the need to understand the enablers and barriers to effective implementation of and compliance with school-based food and beverage policies(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Moore, Murphy and Tapper32) . No review has been published so far that systematically synthesised the evidence on enablers and barriers to school-based food policy implementation. Therefore, the aim of this systematic literature review and meta-synthesis was to explore and synthesise these enablers and barriers.

Methods

Study design

Reporting of this review is in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33). The protocol for this review prospectively was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42017078940). No major changes were made to the original protocol submitted.

Search strategy

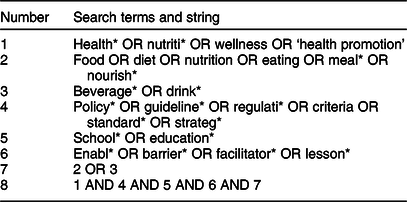

A search strategy was developed by the research team in consultation with a research librarian at the Australian Catholic University. The research question was developed using the Population Intervention Comparison Outcome framework(Reference Schardt, Adams and Owens34): what are the enablers and barriers (O) to implementation of and compliance with healthy food and beverage policies (I) in schools (P)? A comprehensive literature search was carried out in June 2019 with eight electronic databases: Medline (EBSCO Host), Scopus, Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, SocINDEX and Business Source Complete. These databases afford a broad coverage of nutrition and public health literature. The search terms and strings used in the systematic review and meta-synthesis are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 Search terms and strings used in literature review and meta-synthesis

Study selection

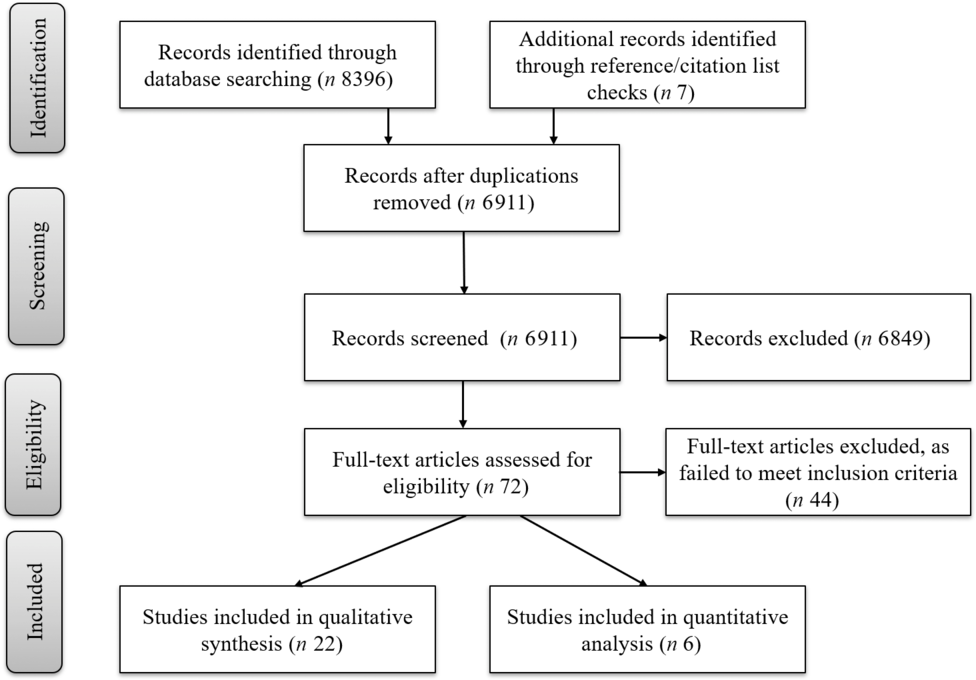

Two reviewers conducted an initial search for relevant studies. We extracted studies identified via the search to an EndNote version 8 (Thomson Reuters 2017) reference library. Duplicates were automatically identified and removed. Two reviewers independently screened each abstract to identify studies that potentially met the eligibility criteria. Then, two reviewers retrieved and independently screened full-text articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through a discussion and consultation with a third reviewer. Two reviewers screened the reference lists of included studies to identify any additional studies. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33) was used to document the number of articles at each screening stage (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the literature search and review process

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported on implementation and/or compliance of food and/or beverage policies in school settings, including primary and secondary schools, with outcomes relating to enablers and/or barriers. For this review, an enabler was defined as ‘a person or thing that makes something possible’; a barrier was defined as ‘a circumstance or obstacle that keeps people or things apart or prevents communication or progress’(35); policy implementation was defined as ‘putting into place new policies and procedures with the adoption of an innovation as the rationale for the policies and procedures’(Reference Fixsen, Naoom and Blasé36); and compliance/adherence referred to compliance of newly implemented policy requirements. Studies that explored enablers and barriers to implementation and/or adherence to healthy food and/or beverage policy relating to nutrition guidelines, regulations and/or restrictions on food and beverages availability, advertisement, placement or price were included. Studies that investigated views about potential implementation of healthy food and beverage policies were excluded. There were no restrictions on study design or study approach (e.g. qualitative or quantitative), year of publication or language.

Data extraction

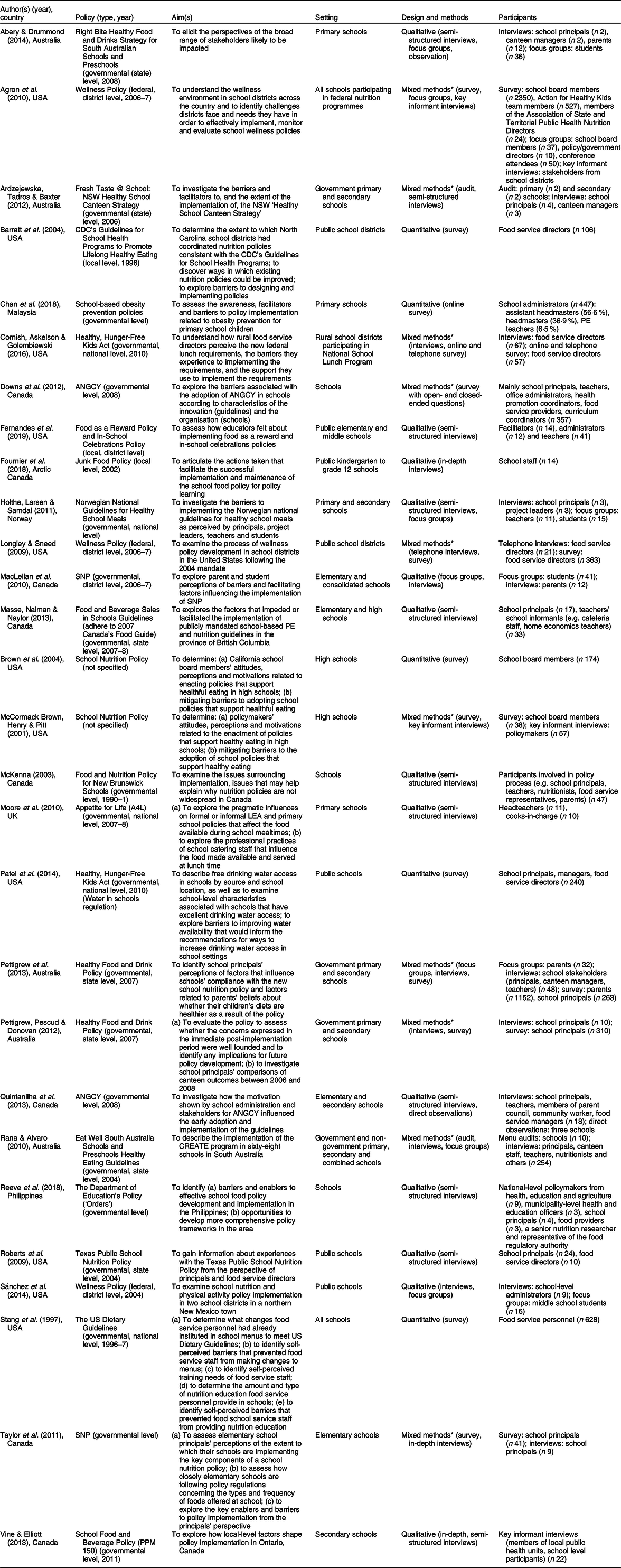

A data extraction worksheet was developed based on the American Dietetic Association guidelines(37) for a comparison of included studies. A pilot extraction of two eligible studies was conducted by two reviewers independently. After comparing the results, minor modifications were made to the data extraction worksheet to improve clarity and ensure consistency among reviewers. Then, the reviewers extracted data from the remaining articles. Key information extracted from articles included title, type of policy, year of publication, author(s), study design and methods, aims of the study, population characteristics, food and beverage policy, results (demographic characteristics and all results relating to barriers and enablers of policy implementation), and potential studies from the reference list. This information is summarised in Table 3.

The quality of individual studies was assessed by two researchers independently using the Appraising the Evidence: Reviewing Disparate Data Systematically checklist(Reference Hawker, Payne and Kerr38). This tool was developed to assess the quality of a diverse group of empirical studies, taking into account not just traditional measures of quantitative rigour but also the quality criteria of qualitative studies. This tool includes nine criteria that assess the practical applicability and scientific validity of each study. The quality attributes of each study were classified as ‘good’, ‘fair’, ‘poor’ and ‘very poor’. In-depth description of each rating criterion can be found in the online supplementary material of the original publication(Reference Hawker, Payne and Kerr38). The overall quality score was calculated for each individual study (0 very poor; 27 good). Then, the overall quality was classified as high (≥70 % of total score), medium (60–69 %) or low (<60 %). The outcomes of quality assessment are provided in Table 2.

Table 2 Quality assessment attributes for each study assessed using the Appraising the Evidence: Reviewing Disparate Data Systematically checklist

G, ‘good – 3 points’; F, ‘fair – 2 points’; P, ‘poor – 1 point’; VP, ‘very poor – 0 point’; L, low quality; M, medium quality; H, high quality.

Table 3 Characteristics of included studies (n 24) that explored enablers and barriers to implementation and compliance of school-based healthy food and beverage policies

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; PE, physical education; ANGCY, Alberta Nutrition Guidelines for Children and Youth; SNP, School Nutrition Policy.

* Qualitative data were extracted from mixed-methods studies that explored enablers and/or barriers to implementation and adherence to healthy food and beverage policies.

Data analysis and synthesis

Findings from quantitative studies that reported on enablers and barriers to implementation and/or compliance of school-based healthy food and beverage policies were summarised. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) guided the quantitative synthesis(Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie39). TDF provides a method for theoretically assessing implementation-related barriers and enablers and is commonly used in clinical and community settings(Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam40). The framework includes fourteen theoretical constructs: knowledge; skills; professional role and identity; beliefs about capabilities; optimism; beliefs about consequences; reinforcement; intentions; goals; memory, attention and decision; environmental context and resources; social influences; emotion; and behavioural regulation. A meta-synthesis approach was used to synthesise findings from qualitative studies. This approach systematically integrates qualitative evidence emerging from multiple studies to enhance the generalisability of each individual qualitative study(Reference Sandelowski, Docherty and Emden41,Reference Jensen and Allen42) . Thematic analysis was used in this meta-synthesis following the steps described by Thomas and Harden(Reference Thomas and Harden43). The initial analyses of quantitative and qualitative studies were conducted by the lead reviewer. First, the reviewer summarised the findings by coding barriers and enablers identified from the quantitative data to the relevant TDF constructs. Then, the reviewer coded the qualitative data extracted from the ‘results’ or ‘findings’ section of each study to develop descriptive themes and subthemes. The coded data were categorised either as ‘enabler’ or ‘barrier’ for each identified subtheme. In order to ensure the trustworthiness of data extraction, two among the rest of authors read drafts of the initial themes and descriptions. Then, the reviewers generated analytical themes based on descriptive themes, and a final version was agreed upon by all the reviewers.

Results

Search results and characteristics of included studies

The search yielded 6911 non-duplicate records. After screening the title and abstract, seventy-two full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which twenty-eight met the inclusion criteria. A description of included studies is shown in Table 3. Nearly half of the studies (n 11) were conducted in the United States(Reference Agron, Berends and Ellis44–Reference Fernandes, Schwartz and Ickovics54), eight in Canada(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Vine and Elliott55–Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61) , five in Australia(Reference Abery and Drummond62–Reference Rana and Alvaro66) and one each in the United Kingdom(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33), Norway(Reference Holthe, Larsen and Samdal67), Philippines(Reference Reeve, Thow and Bell68) and Malaysia(Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69). Most studies (n 21) focused on both primary and secondary schools(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Agron, Berends and Ellis44–Reference Longley and Sneed47,Reference Patel, Hecht and Hampton50–Reference Fernandes, Schwartz and Ickovics54,Reference Quintanilha, Downs and Lieffers57–Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63–Reference Reeve, Thow and Bell68) , four on primary schools exclusively(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference Abery and Drummond62,Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) and three on secondary schools only(Reference McCormack Brown, Henry and Pitt48,Reference Brown, Akintobi and Pitt49,Reference Vine and Elliott55) . Nearly all policies (n 23) were developed at governmental/federal levels. Most studies were conducted with school principals (n 19) and/or food providers (n 13), and some studies included teachers (n 8), school board members (n 5), parents and/or students (n 3). Studies were published between 1997 and 2019, with most (n 21) being conducted after 2010, and no studies published in other than the English language were considered.

Of the twenty-eight included studies, thirteen were qualitative investigations(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33,Reference Roberts, Pobocik and Deek51,Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52,Reference Fernandes, Schwartz and Ickovics54,Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Quintanilha, Downs and Lieffers57–Reference MacLellan, Holland and Taylor59,Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61,Reference Abery and Drummond62,Reference Holthe, Larsen and Samdal67,Reference Reeve, Thow and Bell68) , five were quantitative(Reference Barratt, Cross and Mattfeldt-Beman45,Reference Brown, Akintobi and Pitt49,Reference Patel, Hecht and Hampton50,Reference Stang, Story and Kalina53,Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) and ten used mixed-methods approaches(Reference Agron, Berends and Ellis44,Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46–Reference McCormack Brown, Henry and Pitt48,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63–Reference Rana and Alvaro66) . However, out of the ten mixed-methods studies, nine used qualitative approaches(Reference Agron, Berends and Ellis44,Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference McCormack Brown, Henry and Pitt48,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63–Reference Rana and Alvaro66) and one(Reference Longley and Sneed47) used a quantitative approach to explore enablers and barriers. Therefore, twenty-two studies were included in the meta-synthesis and six in quantitative analysis. All the quantitative studies collected data through surveys(Reference Barratt, Cross and Mattfeldt-Beman45,Reference Longley and Sneed47,Reference Brown, Akintobi and Pitt49,Reference Patel, Hecht and Hampton50,Reference Stang, Story and Kalina53,Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) . Only four studies provided psychometric properties of their measurements, of which three studies(Reference Brown, Akintobi and Pitt49,Reference Patel, Hecht and Hampton50,Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) used content validity and two(Reference Barratt, Cross and Mattfeldt-Beman45,Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) used face validity to review their surveys. Semi-structured/in-depth interviews and/or focus groups were the most common data collection methods used by the qualitative studies (n 21)(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33,Reference Agron, Berends and Ellis44,Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference McCormack Brown, Henry and Pitt48,Reference Roberts, Pobocik and Deek51,Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52,Reference Fernandes, Schwartz and Ickovics54–Reference MacLellan, Holland and Taylor59,Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61–Reference Reeve, Thow and Bell68) . One study used a survey with open-ended questions to collect qualitative data(Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60).

Study quality

Overall, the quality of studies was generally classified as good, with 79 % achieving high overall quality rating and only 8 % being rated at low quality (Table 2). However, many studies lacked detailed information regarding methodology (e.g. sampling and data analysis) and transferability criteria. Most importantly, a majority of the studies (n 22) used a qualitative approach, so the transferability/generalisability criterion may not apply. Most studies received a ‘good’ or ‘fair’ rating for the abstract, introduction, results/findings, ethics/bias and implications/usefulness of study criteria. Only five studies received a ‘good’ rating for data analysis.

Quantitative findings

Enablers

Only three studies reported enablers for a healthy food and beverage policy implementation(Reference Longley and Sneed47,Reference Brown, Akintobi and Pitt49,Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) , which fit within the TDF constructs of ‘social influences’, ‘knowledge’, ‘professional role and identify’ and ‘environmental context and resources’. These studies reported that support from school staff members and concerns for children’s health contribute to a successful implementation of a healthy food and beverage policy. Most school staff (52 % of respondents) supported practices encouraging health-promoting food choices, such as banning soft drink advertisements and fast-food sales in primary schools(Reference Brown, Akintobi and Pitt49). One-third of school district directors (36 % of respondents) stated that staff’s concerns for children’s health support the development and implementation of policy(Reference Longley and Sneed47). School administrators from Malaysia stated that school-based food policy is seen as a school’s responsibility (71 %) and a priority (83 %), which enabled better policy implementation.

Barriers

Several barriers that undermined implementation and compliance with healthy food and beverage policies were identified. Five studies reported barriers relating to the TDF construct ‘social influences’(Reference Barratt, Cross and Mattfeldt-Beman45,Reference Longley and Sneed47,Reference Brown, Akintobi and Pitt49,Reference Stang, Story and Kalina53,Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) . These studies reported a lack of policy implementation support and training for school staff, poor acceptance of healthy foods by the school community, and unhealthy fundraising practices such as ‘bake sales’ as barriers to implementation and compliance with healthy food and beverage policies. Five studies reported barriers relating to the TDF construct ‘environmental context and resources’(Reference Barratt, Cross and Mattfeldt-Beman45,Reference Longley and Sneed47,Reference Patel, Hecht and Hampton50,Reference Stang, Story and Kalina53,Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) . These studies identified the costs associated with policy implementation as a significant barrier. The costs associated with healthier foods such as fresh foods, lower-fat and lower-sodium foods(Reference Barratt, Cross and Mattfeldt-Beman45,Reference Longley and Sneed47,Reference Stang, Story and Kalina53) , equipment(Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69) or installation of facilities such as drinking water fountains(Reference Patel, Hecht and Hampton50) were identified as barriers by food service providers and school principals. Three studies identified barriers relating to the TDF construct ‘goals’(Reference Longley and Sneed47,Reference Brown, Akintobi and Pitt49,Reference Patel, Hecht and Hampton50) , for example, food and nutrition policy not being a priority. In addition, one study reported barrier relating to the TDF construct ‘reinforcement’(Reference Chan, Moy and Lim69), such as stating that there were no effect on non-compliance.

Qualitative findings

Five key themes emerged regarding the enablers and barriers to implementation of and compliance with school-based healthy food and beverage policies: (i) financial impact, (ii) physical food environments, (iii) characteristics of the policy, (iv) stakeholder engagement and (v) organisational priorities. The identified themes, subthemes and select quotes are presented in the online supplementary material.

Financial impact

This theme consisted of six subthemes: (i) policy-compliant food costs, (ii) changes in profit/revenue, (iii) human resources, (iv) funding, (v) fundraising and (vi) food wastage. Only four studies reported positive or no financial impact after the implementation of healthy food and beverage policy(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52,Reference Pettigrew, Pescud and Donovan65) . A majority of studies (n 14) reported that the implementation of healthy food and beverage policy had a negative financial impact, such as stating that policy-compliant foods costed more(Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Abery and Drummond62,Reference Rana and Alvaro66) and reduced profits and revenue(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33,Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference McCormack Brown, Henry and Pitt48,Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference McKenna58,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Abery and Drummond62,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63,Reference Holthe, Larsen and Samdal67,Reference Reeve, Thow and Bell68) .

Some school stakeholders reported a loss of catering/canteen staff due to a reduction of profits(Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Holthe, Larsen and Samdal67) , and some schools ran lunch programmes through volunteers who had minimal food preparation and policy compliance knowledge(Reference MacLellan, Holland and Taylor59,Reference Abery and Drummond62) . Students discarding healthy foods or food service staff preparing excessive quantities of perishable food was identified as a barrier to policy implementation(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33,Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46) . In addition, some schools reported fundraising involving selling unhealthy foods such as ‘candy’, ‘soft drinks’, ‘chips’ and ‘donuts’(Reference Roberts, Pobocik and Deek51,Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52) . This was seen as a major barrier to compliance with healthy food and beverage policy by school principals, administrators and students.

Physical food environments

This theme consisted of four subthemes: (i) policy-compliant food availability, (ii) geographical proximity of unhealthy foods, (iii) nexus between home and school and (iv) resources. None of the studies reported enablers associated with the physical environment impacting policy implementation. Policy-compliant food availability was reported as a barrier in four studies(Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60) . These studies indicated that it is challenging to find suppliers who can supply policy-compliant foods.

Geographical proximity of food outlets mainly selling discretionary foods was identified as a major barrier in seven studies(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52,Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63,Reference Holthe, Larsen and Samdal67,Reference Reeve, Thow and Bell68) . These studies stated that food outlets around schools selling unhealthy foods to schoolchildren consequently affect policy implementation and the profits of food providers within schools. Interestingly, one study stated that the school authority worked with a neighbourhood store manager to reduce sale of unhealthy food during school hours, which positively impacted policy implementation(Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61). The home environment, including unhealthy foods brought from home, lack of parents’ support to policies and low levels of food literacy, was seen as barriers for policy implementation and compliance in five studies(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff33,Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52,Reference Quintanilha, Downs and Lieffers57,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63) . In addition, some schools were unable to fully implement healthy food and nutrition policy due to a lack of facilities, including reduced operating hours of the canteen(Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Holthe, Larsen and Samdal67) .

Characteristics of the policy

This theme consisted of four subthemes: (i) knowledge and understanding of the policy, (ii) policy communication and clarity, (iii) management of the policy and (iv) accountability. Studies reported that school-based policies were often unclear and ‘open to interpretation’, and some stakeholders were treating school policy as not mandatory or lacking policy application knowledge(Reference Mâsse, Naiman and Naylor24,Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference McCormack Brown, Henry and Pitt48,Reference McKenna58,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Abery and Drummond62,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63) .

A lack of dialogue with targeted people during policy drafting stage, a lack of clarity and the use of a ‘dictatorial voice’ in policy statements were seen as barriers in healthy food policy implementation and compliance(Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference Roberts, Pobocik and Deek51,Reference McKenna58,Reference MacLellan, Holland and Taylor59,Reference Abery and Drummond62) . School stakeholders stated that they were not consulted during policy development as the policy was developed from a ‘top-down’ approach. Some stakeholders were overwhelmed with sudden changes required following the introduction of new policy and suggested that it needed to be a gradual process. Indeed, one study reported policy implementation by a ‘harm reduction’ approach where the policy on unhealthy foods was introduced gradually, which acted as an enabler(Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61). Only three studies reported policy communication as an enabler, stating that school stakeholders were well informed about the policy and the reasons for change(Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61,Reference Pettigrew, Donovan and Jalleh64,Reference Pettigrew, Pescud and Donovan65) .

Good policy introduction and implementation was seen as an enabler to implementation and compliance. Examples include a constant review of compliance with policy, a collaborative approach to decision-making, and collaboration between different state agencies such as education, agriculture and health(Reference Agron, Berends and Ellis44,Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Quintanilha, Downs and Lieffers57,Reference McKenna58,Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63,Reference Pettigrew, Donovan and Jalleh64) . One study reported poor management practices as a barrier to policy implementation as it was left up to each individual school to implement, without providing a broader implementation framework or assistance(Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52). Lack of accountability was also seen as a barrier to compliance with the healthy food and beverage policy(Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52).

Stakeholder engagement

This theme consisted of four subthemes: (i) attitudes of school staff, (ii) students’ preferences and attitudes, (iii) attitudes of parents and (iv) big food (industrial, convenience food producers and manufacturers) influence. Nine studies reported negative attitudes of school staff(Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference Roberts, Pobocik and Deek51,Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference McKenna58–Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Abery and Drummond62,Reference Holthe, Larsen and Samdal67) towards healthy food and beverage policies, and only four studies reported positive attitudes(Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference Quintanilha, Downs and Lieffers57,Reference McKenna58,Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61) . Such attitudes reportedly impacted policy implementation and compliance. The main basis of negative attitudes included: teachers should not be responsible for students’ dietary choices; food choices should not be limited; and disagreements regarding the provision of food rewards for students and limiting fundraising opportunities involving unhealthy foods, such as confectionary. One study reported a lack of motivation in implementing policies, for example, school principals being overwhelmed with what they need to deliver(Reference Reeve, Thow and Bell68).

Students’ preferences and demands for unhealthy foods reportedly impacted healthy food and beverage policy implementation and compliance in eight studies(Reference Moore, Murphy and Tapper32,Reference Sánchez, Hale and Andrews52,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference MacLellan, Holland and Taylor59–Reference Fournier, Illasiak and Kushner61,Reference Ardzejewska, Tadros and Baxter63,Reference Holthe, Larsen and Samdal67) . Some studies stated that demands for unhealthy foods and loss of canteen sales led to deliberate compliance breaches. However, some respondents reported receiving no complaints from students regarding policy-compliant foods and described the policy implementation process as ‘smooth’(Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference Taylor, Maclellan and Caiger56,Reference MacLellan, Holland and Taylor59,Reference Pettigrew, Pescud and Donovan65) . The respondents also observed positive dietary behaviours such as increased consumption of fruit and vegetables and acceptance of other healthy foods.

Some studies reported parents as a barrier to healthy food and beverage policy implementation(Reference Quintanilha, Downs and Lieffers57,Reference Downs, Farmer and Quintanilha60,Reference Abery and Drummond62) . Specifically, parents viewed that policy implementation eliminated students’ freedom to choose what to eat or buy(Reference Quintanilha, Downs and Lieffers57). Other respondents indicated that some parents are very proactive and support the healthy food and beverage policy(Reference Quintanilha, Downs and Lieffers57,Reference MacLellan, Holland and Taylor59,Reference Pettigrew, Pescud and Donovan65) . In addition, two study reported that Big Food companies (e.g. Pepsi, Coca-Cola, McCain Foods, etc.) had a negative influence on policy implementation. For example, some argued that schools are denying students’ choices(Reference McKenna58), and in Philippines, Big Food was often involved in advertising unhealthy foods and providing sponsorship(Reference Reeve, Thow and Bell68).

Organisational priorities

This theme consisted of two subthemes: (i) academic performance and (ii) other competing priorities. Some respondents, mainly teachers and school principals, argued that academic performance is a school’s top priority(Reference Agron, Berends and Ellis44,Reference Cornish, Askelson and Golembiewski46,Reference McCormack Brown, Henry and Pitt48,Reference Vine and Elliott55,Reference Abery and Drummond62,Reference Masse, Naiman and Naylor70) , and schools are under pressure to improve academic performance of their students. Therefore, food and nutrition policy is not a priority. Some respondents indicated that the policy implementation would lead to students going hungry due to policy-compliant foods being unpopular among students, and this might lead to low participation in class and consequently poor learning and academic performance. In addition, one study reported teachers as having stated that healthy food policy is insensitive to students’ needs as children in disadvantaged communities often come hungry; therefore, teachers lacked motivation in implementing such policies(Reference Fernandes, Schwartz and Ickovics54).

Discussion

The aim of this systematic literature review and meta-synthesis was to explore enablers and barriers to effective implementation and compliance with school-based food and beverage policies. Five themes were identified through a meta-synthesis as enablers and barriers to the implementation and compliance with healthy food and beverage policies, and there was an alignment between the findings of studies using quantitative and qualitative methods. The most commonly reported barriers included costs and availability associated with policy-compliant foods, decrease in profit and revenue, close proximity of outlets selling unhealthy food, lack of human and material resources for implementation, poor knowledge and understanding of the policy, and negative attitudes of stakeholders towards the policy. Only a few policy implementation enablers were identified, including sufficient funding, effective policy communication and clarity, good policy implementation process, and positive attitudes of stakeholders towards policies. Similar findings have been observed in a systematic literature review on the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in a school setting(Reference Nathan, Elton and Babic71), showing that broader recommendations could be drawn for organisations working on any school-based policy implementation.

A particularly strong theme was financial barriers. Several studies stated that healthy foods cost more, and school canteen’s profits and revenue decreased post-implementation. This reportedly forced some schools to seek fundraising opportunities, which involved unhealthy foods to recover lost profits. However, one study suggested that most schools did not experience any overall losses in revenue associated with the implementation of school-based healthy food and beverage policies(Reference Wharton, Long and Schwartz72). Moreover, in a randomised controlled trial of the implementation of a healthy canteen policy in Australia, there were no adverse financial effects of policy implementation on canteen revenue(Reference Wolfenden, Nathan and Janssen73). Communicating such evidence prior to policy implementation may help allay school staff’s concerns and reduce the salience of this barrier. However, the costs associated with healthy foods was found to be a key driver in consumer choice(Reference Faber, Laurie and Maduna74). One strategy to reduce the costs of healthy foods includes the introduction of cross-subsidy pricing strategies, where revenues generated via increases in the price of less-healthy foods may be used to reduce the prices of more-healthy options(Reference Mozaffarian, Angell and Lang75). The engagement of schools in a food cooperative or purchasing healthy foods at lower prices through shared purchasing of foods may represent another potential strategy to address this barrier(Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien19,Reference Grech and Allman-Farinelli76) .

A number of studies reported difficulty in sourcing policy-compliant foods and beverages, consistent with research in a health service setting(Reference Boelsen-Robinson, Backholer and Corben77). It might be that food catering managers and staff need more support from nutritional experts (e.g. dietitians and nutritionists) to enable the identification of compliant foods. In addition, canteen managers could advocate food companies to reformulate their products to meet healthier standards, thereby increasing the breadth of healthier options for canteen managers to choose from(Reference Buttriss78). For example, in the United Kingdom, the Responsibility Deal’s Food Network was established in 2011 to engage the food industry in reformulating foods by reducing salt content, trans fatty acids and energy content(Reference Buttriss78).

Lack of knowledge and understanding of the healthy food and beverage policy was another commonly cited barrier for policy implementation and compliance. Failing to understand the policy’s purpose might also create negative stakeholder attitudes. Positive attitudes towards policy were identified as an enabler for the implementation of policies, but most studies reported negative attitudes from teaching staff, parents and students. The main argument regarding negative attitudes was that healthy food and beverage policy restricted students’ choices and the lack of consultation with stakeholder during policy development. While some stakeholders were concerned that policies restricted students’ choices, a recent Australian study showed that students are in favour of eliminating unhealthy foods and increasing access to nutritious foods in school canteens(Reference Stephens, McNaughton and Crawford79). To address the negative attitudes, stakeholder engagement should be included during policy development. Stakeholder involvement and engagement could help identify any potential barriers early in the process(Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsley80). Indeed, a study reported that staff, parent and student involvement in healthy food and beverage policy implementation showed better outcomes such as reduced availability of nutrient-poor foods(Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsley80). While stakeholder engagement may improve attitudes, monitoring of healthy food and beverage policies might be the best option for effective adherence, as some studies stated that a lack of monitoring services is the reason for non-compliance. For example, Swinburn et al. (Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Rutter81) stated that there is a need to move from responsibility to accountability for a successful implementation of healthy food policy. Accountability may enhance adherence to healthy food policy. Therefore, there is a need to establish governmental agencies and develop monitoring initiatives to ensure that schools are made accountable for breach of compliance with healthy food and beverage policies(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Rutter81–Reference Lucas, Patterson and Sacks83).

Limitations of the study

Our review provides a comprehensive literature analysis of enablers and barriers relating to healthy school-based food and beverage policy implementation and compliance using both quantitative and qualitative methods. However, limitations should be acknowledged. Although we used a systematic search protocol, it might be that some relevant publications were missing, such as governmental evaluation reports. The low-to-moderate quality relating to transferability/generalisability and data analysis of qualitative studies suggests the need to conduct additional research in different countries and more thorough reporting of analytical methods in the future studies. Qualitative researches need to provide more detailed information on methods used in data analysis. In terms of transferability, we tried to address this limitation through meta-synthesis, which enhanced the transferability of each individual qualitative study(Reference Sandelowski, Docherty and Emden41,Reference Jensen and Allen42) .

Conclusion and recommendations for future research and practice

When implemented successfully, school food policies have been consistently found to be of benefit to students’ dietary outcomes(Reference Jaime and Lock15). Despite this, the implementation of such policies in many international jurisdictions remains limited(Reference Hills, Nathan and Robinson84). This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of research evidence regarding the enablers and impediments to food policy implementation, with a view to inform strategy development in support of public health policy implementation(Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West85). The findings of this review, therefore, inform school-based nutrition policymakers about a variety of factors that need to be considered during the development and implementation of such policies. Given the nascent state of implementation research in the field of school-based nutrition(Reference Wolfenden, Nathan and Sutherland86), our review also provides good grounding for the testing of strategies to improve the implementation of nutrition policies. To date, only few randomised controlled trials have aimed to improve the implementation of school-based healthy eating policies or practices by reducing the barriers identified in the literature(Reference Wolfenden, Nathan and Janssen73,Reference Rabin, Glasgow and Kerner87) .

The findings of our systematic review suggest several important directions for future research. First, the low-to-moderate quality of evidence suggests that higher-quality evidence with a specific focus on improving the data analysis of qualitative studies is required. Most of the included studies were conducted in English-speaking countries, and all were conducted in established western economies. Since the health effects of poor food and beverage intake is a global problem, more research is needed to evaluate policies being implemented in emerging economies. Also, future research should investigate the differences in policy implementation between different types of schools, as most studies included in this review focused on only primary and secondary schools. Some evidence suggests that food environments, including policies and regulations, tend to be overlooked in secondary schools(Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast88). Finally, the limited amount of research in this area suggests that many school-based policies have been scarcely evaluated in terms of barriers and enablers, or that these evaluations remain to be disseminated. We would urge researchers to engage with stakeholders to ensure that new and existing school-based policies are thoroughly evaluated.

The findings of this systematic review provide policymakers with strategies to improve the implementation and compliance of new policies. These strategies include ensuring a reporting or monitoring component to improve compliance and address school’s concerns prior to policy implementation. Policymakers may also need to ensure that schools are provided with sufficient resources and support to implement the policy and all stakeholders are involved during policy development and implementation stages.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Associate Professor Jason Wu for insightful and helpful feedback on this manuscript. Financial support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The study also did not receive any specific non-financial support. Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest was declared. Authorship: R.R. developed the research question and drafted a protocol. All authors reviewed and accepted the protocol. R.R. and N.R. conducted the searches, screening, data extraction and quality assessment. A.W. acted as a third reviewer in this process. R.R. coded and analysed quantitative and qualitative data under the supervision of A.W., T.S. and C.L. L.W. R.R. and N.R. drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript and declare this content has not been published elsewhere. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required because the submitted article is a systematic review, and the findings of existing studies are available in the public domain. The protocol for this review prospectively was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42017078940) and can be accessed at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this article visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019004865