The Afro-American Papers are the only ones which will print the truth, and they lack means to employ agents and detectives to get at the facts. The race must rally a mighty host to the support of their journals, and thus enable them to do much in the way of investigation.

–Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Lynch Law in All its Phases (1892, p. 23)Introduction

Recent police killings of unarmed Black people, subsequent acquittals of officers involved, and worldwide protests have once again brought issues of racism in policing to the national forefront. The 2020 protests for George Floyd and Breonna Taylor; the 2015 uprisings in Baltimore, Maryland and Ferguson, Missouri for Freddie Grey, Michael Brown; and many more are all part of a long history of Black protest in response to police violence dating back to the 1960s and even further back to revolts against slave patrols in the early colonial period (Logan and Oakley, Reference Logan and Oakley2017; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Giacopassi and Vandiver2007).

Recent research has considered the impact of high levels of police contact and police use of force as it relates to mass incarceration (Hinton Reference Hinton2015; Rios Reference Rios2009, Reference Rios2017), deleterious health effects (Sewell and Jefferson, Reference Sewell and Jefferson2016), increased deportation (Armenta Reference Armenta2017; Golash-Boza Reference Golash-Boza2014), overall trust in police (Desmond et al., Reference Desmond, Papachristos and Kirk2016; Fox-Williams Reference Fox-Williams2018), as well as attitudes toward local and national authorities more broadly (Lerman and Weaver, Reference Lerman and Weaver2014). Studies post-Ferguson find that mainstream news representations largely support official police narratives of instances where Black victims are killed by police, and that digital media is often used to challenge these narratives (Bonilla and Rosa, Reference Bonilla and Rosa2015; Stone and Socia, Reference Stone and Socia2017). Less understood is how public contestation of official police reports, within and beyond press media, following publicized instances of police violence, is related to local and global civic action over time. The present study examines how police narratives are taken as fact or challenged in reporting from two widely read news sources—one Black-owned weekly, the other a mainstream daily—in New York City, pertaining to two separate police killings in the same neighborhood and police precinct, thirty-three years apart.

This study analyzes news coverage following the police killings of ten-year-old Clifford Glover in 1973, and twenty-three-year-old Sean Bell in 2006, eventual officer acquittals, and ensuing protests in one community: Jamaica, Queens, New York. I use critical discourse analysis to evaluate news descriptions of community residents, protesters, civic and faith leaders, as well as officers and victims involved in the police killings and ensuing trials.

While offering analysis of mainstream news sources’ accounts of police violence and unverified police reports, this study also makes transparent the positionality of Black News sources in historically addressing the persistence of police violence and the propagation of police narratives following officer-involved fatalities, taking an assets-based approach to understanding Black journalistic agency in the wake of American police killings. This is a chocolate city (Hunter and Robinson, Reference Hunter and Robinson2018) analysis focusing not solely on the role of state institutions in perpetuating racial inequity in Black communities, but also the central role of Black-owned-and-operated institutions, in the making and remaking of social conditions, challenging police authority in court, in the news, and on the streets.

Using the comparative case of Black Press and White Press reporting on the 1973 police killing of Clifford Glover and the 2006 police killing of Sean Bell, both in the NYPD 103rd Precinct of Jamaica, Queens, New York, I ask the following: 1) How do newspaper media depict the actions and character of police officers and victims when police kill unarmed people in the same community over time? and 2) How do Black press and White press differentially report the actions of community residents and leaders after police killings and officer acquittals?

Expanding upon research of urban Black political and social movements with attention to police power and news reporting, this article draws on newspaper coverage from The New York Times and the New York Amsterdam News to assess reporting on two separate police killings and officer acquittals.

Using the linguistic method of critical discourse analysis, guided by conceptual metaphor theory (Lakoff and Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980)—the theory that our everyday language about social matters is guided by overarching metaphors—I analyze news coverage of the police killings of Glover and Bell, in both cases caused by gunshots fired by undercover officers from the New York Police Department (NYPD) 103rd Precinct. I chose these two instances of police violence because their study is essential to a longer community history of policing in Jamaica, Queens over time and because both police killings had resonant outcomes for policing throughout the city of New York.

I comparatively study news coverage of police violence, across time, within one community and NYPD police precinct with the aim of contributing to current scholarship on both localized institutional histories of police violence and racialized discourse about victims of police violence in communities where police use of force is concentrated. Central to understanding current social movements against the expansion of police and police powers in the urban—as well as suburban and rural—United States is the disentanglement of discourse around fatalities caused by police. News reporting on officers involved and victims of lethal police use of force informs how the public understands police killings, police work, and the role of government itself. This means that perceptions of individual incidents of police violence inform overall beliefs and opinions about the police and potentially impact civic participation (Lerman and Weaver, Reference Lerman and Weaver2014).

The findings of this study elucidate crucial aspects of news reporting following fatal police shootings, namely the ways that Black and White News sources differentially frame the same incidents. This article argues that Black Press and White Press engage in similar discourses about what occurred during two separate police killings, one of a boy and one of a young man, in the same neighborhood, decades apart, but often in contested ways. I also argue that both newspapers fall short of delivering the full historic context of localized police violence over time in this community.

First, what I term ‘no angel’ discourse is used by White Press to adultify youth and vilify, criminalize, and further dehumanize Black victims of police violence as well as their families and close associates. Any instance in which efforts are made to highlight police reporting on why the officers were justified in opening fire on Black victims is analyzed under the subheading of ‘no angel’ discourse. Black Press utilizes this discourse to a far lesser degree to describe victims, and additionally points criticism back at the officers involved and reports on a previous pattern of misconduct that may be predictive of violence and murder. They also question parallel police investigations conducted to try and retroactively justify police shootings in the face of litigation. Second, the conceptual metaphor community as disaster Footnote 1 is utilized by both Black and White Presses to depict the fear of violence and “civil disorders” in the aftermath of police killings and officer acquittals. Though utilized differently, and while Black Press amplifies voices from a wider array of community members and leadership, the panic around a city’s “eruption” following police violence is employed similarly. Thirdly, both presses contribute to a “discontinuity” or loss of memory as neither press references the prior police killing of Clifford Glover in relation to the police killing of Sean Bell, even though both took place in the same community and precinct and bear other revealing similarities.

Overview and Framework

Collective Memory and Police Violence

Mistrust of state institutions, local municipal police, as well as federal authorities, is historically informed. For Black communities that have endured various forms of racial injury, abuse, and discrimination from public and private institutions, contemporary incidents of police misconduct and violence are part of a historical continuum. This local collective reservoir of information is the result of a rich reserve of memory often absent from dominant productions of knowledge and history (Nora Reference Nora1989), but evident among Black people in Black space (Anderson Reference Anderson2014) due to the persistence of Black oral tradition (Brown Reference Brown2016), Black documentation and publication (Wells-Barnett Reference Wells-Barnett1892), and Black political struggle (Gregory Reference Gregory1999; Hunter Reference Hunter2013, Morris Reference Morris1984).

Black space, as understood by Elijah Anderson (Reference Anderson2014) describes those parts of American cities that are relegated to where “the Black people live.” It is understood in opposition to White space, where Black people are not to be found residing, or in relation to the Cosmopolitan Canopy, where these two worlds may collide, momentarily without tension or disruption. The present study considers how police violence is publicly and historically understood, concentrated in Black space or the “Black Belts” of American Cities (Drake and Cayton, Reference Drake and Cayton1945).

Elucidating the impact of police violence on individual neighborhoods and cities starts with revisiting incidents of police violence and collective action in urban Black communities that have received national attention. Riots erupted routinely in urban centers in response to unjust police practices during the mid-twentieth century. The riots in Watts, California, Newark, New Jersey, and Detroit, Michigan are the most notable of the 1960s, each necessitating federal intervention (Parenti Reference Parenti2015) and provoking the landmark Kerner Commission Report which famously declared that “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

This article expounds historical research dealing with racialized discourse on urban Black people and police violence and adapts its conceptualization of racialized discourse in press media from Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s (Reference Wells-Barnett1892) classic Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases. In her investigative work, by contrasting the reporting of Black-owned-and-operated newspapers with White ones, she demonstrates that White men’s panic around miscegenation—consensual sexual relations—between White women and Black men was at the core of lynch law, not, as many at the time contended, sexual assault and rape. In fact, in many cases Black men were coerced into sexual activity by White women who threatened their livelihood if they chose not to engage. Whereas Wells-Barnett reports on the role of the “Afro-American Press” in investigating these circumstances surrounding lynch law in the American South, I analyze news reporting on the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century problem of police violence, specifically in New York City, and ask whether similarly racialized depictions of criminality and brutishness are still at play, especially emphasizing the role of Black Press in bringing them to light.

Wells-Barnett (Reference Wells-Barnett1892) refers to “The Malicious and Untruthful White Press” reporting libelous depictions of hypersexual and inherently criminal Black men who must be controlled before their urges engulf them. In using Wells-Barnett’s work as a starting point, I also contribute to research that connects the American era of lynching by mob and contemporary racial disparities in police use of force (King et al., Reference King, Messner and Baller2009).

Following the work of Darnell Hunt (Reference Hunt1997) and Regina Lawrence (Reference Lawrence2000), this article contributes to research on mass media depictions of police violence and collective action in the wake of police officer acquittals following fatal police encounters. Whereas Hunt analyzes racialized audience perceptions of television news during the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, I analyze news discourse on urban uprisings in the wake of police killings in one New York City community and police precinct over time. Lawrence (Reference Lawrence2000) demonstrates how frontpage news coverage of police brutality in mainstream publications like The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times are largely defined by police accounts of incidents, though media visibility does allow the socially marginalized to voice dissent.

Cathy Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1999) exploration of reporting in the New York Amsterdam News guides my conceptualization of Black political struggle and boundary making. Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1999) analysis of depictions of Black gay men and Black drug users troubles how intraracial boundaries were maintained during the AIDS epidemic in determining which Black people’s deaths were worthy of coverage. My analysis cuts across these seminal studies, focusing specifically on the depiction of Black victims of police violence and the collective action that follows police killings, asking what different newsrooms deem worthy of coverage.

This article also extends the essential work of Michael Huspek (Reference Huspek2004). His study explores local White Press and Black Press reporting on the 1998 police killing of nineteen-year-old Tyisha Miller, a young Black woman, while she was unconscious in her car in Riverside, California. Huspek’s theoretically guided empirical analysis of press practices confirms that oppositional views in press replicate the worldviews of their readerships. He argues, as did Wells-Barnett, that White Press distort truth and reality by often erasing the role of race in their reporting altogether and by presuming an unbiased and objective treatment of criminality and police action. He advocates, as did Wells-Barnett, for the significance of Black Press as a means of gaining a more complete understanding of the truth of racial violence instead of, as critics suggest, thinking of non-mainstream, ethnically specific news media as biased or niche and incomparable to the journalistic rigor of White Press. I conduct a similar study to Huspek (Reference Huspek2004), but of police killings of a boy and young man in two different eras in the same community, allowing for historic comparison across time.

In the time following police shootings of unarmed individuals, press media play a pivotal role in discursively setting the tone and providing information on what happened: who was killed, where were they killed, and why were they killed? Consequently, these questions probe the public to consider whether death was a preventable outcome, and whether use of lethal force was at all necessary or justified. Thus, the discourse around victims and perpetrators of police killings informs collective consciousness and memory about police power and the allowable treatment of people by authorized state agents.

Newspapers play an important role in the process of emotion management in the wake of police violence by regulating discourse. According to Michael Schwalbe and colleagues (Reference Schwalbe, Godwin, Golden, Schrock, Thompson and Wolkomir2000), emotional subjectivity can be conditioned in ways that reproduce inequality. This means that news depictions of police killings of unarmed Black children and adults, as well as collective protests in the wake of officer acquittals, could reproduce inequality by conditioning emotional control by those enraged by the actions of officers, judges, juries, and other state actors by encouraging sympathy for officers in their actions during fatal encounters.

This article conceptualizes collective memory as mutually constitutive: the broader national collective memory of events involving police violence and urban uprisings and the local neighborhood memory, in this case of Jamaica, Queens, New York, are simultaneously informed by news coverage from journalists both in local, demographically targeted papers and nationally published mainstream newspapers. Central to this study’s framework is more fully understanding the relationship between the news and collective memory and forthcoming research from the author will more fully capture collective memory of police violence and protest through oral histories with long term neighborhood residents.

Contemporary Police Violence

When police use lethal force and kill both young and adult civilians, people rely on various sources of news to learn about what unfolded during the fatal encounter (Hunt Reference Hunt1997; Lawrence Reference Lawrence2000; Zimring Reference Zimring2017). From the reason for initial contact to escalation of violence and eventual use of force to kill, readers may come across varied and differential accounts of the actions of officers and victims, based on their news source. News media provide crucial information about the events leading up to police officers’ use of deadly force, as well as vital facts—or fictions—about the victims and officers involved. The way these events are described bear meaning for how the public interprets where and why police use lethal force, and for what laws, policies, and practices are at stake.

A landmark example of this phenomenon is how the filmed and highly publicized killing of forty-three-year-old Eric Garner by NYPD 120th Precinct officer Daniel Pantaleo on Staten Island in 2014 led to statewide and national dialogue about the justifiability of police use of chokeholds, despite a state grand jury’s decision not to indict Pantaleo that same year. Another example of police use of lethal force leading to widespread calls for reform is the highly publicized police killing of twenty-six-year-old Breonna Taylor by Louisville Municipal Police Department plainclothes officers in 2020, which sparked national debate about discontinuing no-knock raids and other military-style tactics or otherwise defunding municipal police altogether. This is again following a grand jury decision not to charge officers involved in the death of Breonna Taylor.

Two contemporary instances of news reporting around the victims of high-profile police killings illuminate the tenuous relationship between Black people and the “White Press” following police killings.

The first surrounds the phrase ‘no angel’ as it is used by New York Times writers to describe Michael Brown, the eighteen-year-old who was gunned down by police in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, spurring protests and collective political action nationwide, largely under the banner of #BlackLivesMatter. The New York Times published a controversial profile on Michael Brown who was shot to death by Darren Wilson, a White police officer, in Ferguson, Missouri on August 9, 2014. In it, the author writes “Michael Brown, 18, due to be buried on Monday, was no angel, with public records and interviews with friends and family revealing both problems and promise in his young life” (Eligon Reference Eligon2014). I mention this profile because it informs my first finding: the prevalence of ‘no angel’ discourse in describing Black victims of police shootings.

The second involves a decision of the family of Eric Garner, the father who was asphyxiated by police in the Staten Island borough of New York City, spurring similar protests around the city and country. The family of Eric Garner, following the death of Eric Garner’s outspoken activist daughter, Erica, publicly proclaimed that they would not speak to White reporters about anything pertaining to their family’s loss. This decision sparked outrage from many, as they felt it was unfair to single out White journalists in this way (Harriot Reference Michael2018).

Both of these contemporary instances point to criticism of journalism conducted by “White Press” reporters on Black victims of police violence—as well as their families and communities—and the tense relationship between Black families and communities and the mainstream press, especially following police killings of unarmed Black people.

Perceived (il)legitimacy of, and consequent ramifications for, law enforcement officials when they use deadly force depends greatly on one’s sources of news media (Hall Reference Hall, Critcher, Jefferson, Clarke and Roberts1978; Huspek Reference Huspek2004; Stone and Socia, Reference Stone and Socia2017). News reporting on the officers and victims involved in police killings impacts how the role of local law enforcement officials and police power is understood and imagined, both in its current state and its potential future.

Existing research suggests that news consumption directly impacts perceived police legitimacy. The relationship between engagement with contemporary forms of media, such as online—internet and social media—modes of obtaining news and attitudes toward police are explored in depth by Jonathan Intravia and colleagues (Reference Intravia, Thompson and Pickett2020). They find that consuming “negative” police stories on the internet is associated with perceiving the police as less legitimate. Jane F. Gauthier and Lisa M. Graziano (Reference Gauthier and Graziano2018) find that consumption of Internet news is related to negative attitudes about police and exposure to “negative” news about police impacts perceptions, but only if the coverage is seen as fair. The present study adds to this literature by examining how Black and mainstream press report differently on localized police killings over time and how this impacts perceptions of police.

Current research finds that police officers perceive ‘hostile’ media coverage of policing as negatively impacting civilian attitudes towards police, causing a fear that allegations of misconduct could be a potential consequence (Nix and Pickett, Reference Nix and Pickett2017). Further, research finds that police organizations exploit their relationship with news media to maintain legitimacy in the face of public criticism (Chermak and Weiss, Reference Chermak and Weiss2005). The implications of this relationship between the police and press media require further analysis, with an emphasis on differential and contested coverage of police accounts, especially from mainstream and ethnically targeted news outlets.

Policing in New York City

This research extends urban and public health research on the determinants of policing behaviors and “justifiable” homicides (Gilbert and Ray, Reference Gilbert and Ray2015) as well as the role of race in state and city policing more broadly (Vargas and McHarris, Reference Vargas and McHarris2017). This article adds a specific example of police violence in one neighborhood over time and the pervasiveness of “racial threat” in determining what is a “justifiable” police killing. Similarly, this article also expands upon recent research on police violence and Black crime reporting (Desmond et al., Reference Desmond, Papachristos and Kirk2016) by historically analyzing the communal reception of police following killings of unarmed civilians and officer acquittals. Additionally, the larger context of “ghettoization” as the vehicle for policing Black lives, as theorized by John R. Logan and Dierdre Oakley (Reference Logan and Oakley2017), provides background on policing urban Black communities, which I expand upon with this research study. Further, Geoff Ward (Reference Ward2018) contextualizes the pivotal role of White supremacy as basis for policing practices throughout U.S. history and the centrality of racial social control to policing since its conception as a means of selective law enforcement. These histories, he argues, are living, and must receive this treatment in research.

At the heart of New York City’s policing strategy in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century lies the “Broken Windows” theory of neighborhood disorder and policing. The Broken Windows theory asserts that any form or sign of neighborhood disorder leads to further disorder and crime and the ultimate degradation of a community (Wilson and Wilson, Reference Wilson and Wilson1982). This means that one broken window will ultimately lead to the decline of an entire building because one window left unfixed shows a lack of care about the building’s physical condition. This philosophy, with roots in social psychology, is extended to punish low-level crimes or quality-of-life behaviors, like loitering, vagrancy, graffiti, and jumping turnstiles. Former Police Commissioner Bill Bratton supported a policy of severe punishments for quality-of-life crimes in early 1990s New York City when the metropolis was “plagued” with criminal activity. This mode of policing was credited with contributing to the city’s large drop in violent crime over the past three decades. In April 2015, Bratton, who was once again commissioner under Mayor Bill de Blasio, wrote that he stands by broken windows even when considering charges that the strategy has racially disparate impacts on arrests and incarceration (Kelling and Bratton, Reference Kelling and Bratton2015).

Bill Bratton argues that higher punishments for lower levels of crime are preventative measures and ultimately decrease the number of individuals incarcerated over time. However, many argue that these policies disproportionately affect young Black and Latinx residents and ultimately give them criminal records that lead to further disenfranchisement in education and career opportunities. Through the enactment of more vague loitering and vagrancy laws, higher levels of discretion are now placed in the hands of police officers over determining legal or criminal gatherings in public space. It is in this vagueness of “broken windows”, order-maintenance statutes that racist notions of criminality are legitimized, and Black citizens become subject to widespread police harassment (Roberts Reference Roberts1999). This, Dorothy Roberts argues, is what leads to the subconscious or overt racism affecting decisions over whom to arrest, fine, or verbally warn.

Understanding the vagueness of order-maintenance policing and its implications for racial bias are essential to my research. At present, Native Americans and African Americans are killed by police in the United States at the highest rates, and though the American fact of police violence in minority communities has become recognized in national dialogue, there is much work to be done by social science researchers to study police stops as a primary site of American and global racial formations (Roychoudhury Reference Roychoudhury and Hunter2018). Extending the work of Michael Omi and Howard Winant (Reference Omi and Winant1994), understanding policing and other forms of governmental surveillance as a primary site of racial formation and boundary-making help us to better understand subjectivity and collective consciousness in the current era of virtually unlimited and expanding police power. Brittany N. Fox-Williams (Reference Fox-Williams2018) documents the extent to which “on track” Black youth and young women in New York avoid, manage, and symbolically resist encounters with police. Furthermore, Victor Ray (Reference Ray2019) theorizes that organizations are inherently racialized, and my study contributes to furthering understandings about the racial dynamic of police institutions, as well as mass media, both historically and contemporarily.

Ahistorical representations of police violence present police killings as an issue unique to the contemporary moment. Situating collective resistance to police power requires tracing specific histories of advocacy for reform and justice in the face of suppression. This article addresses the case of one such historic, communal struggle. It is difficult to enumerate the violence endured by urban communities of color at the hands of law enforcement over the past century but one of the most exhaustive documents attempting to do so was presented to the United Nations by its authors William Patterson and Paul Robeson in Reference Patterson1951. The petition, titled “We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People” was presented as proof that the racism of the United States Government and its agencies was a crime punishable under the UN Genocide Convention. The petitioners included several prominent African Americans including foundational sociologist William Edward Burghardt Du Bois.

The crimes outlined in this petition included, among many examples of systematic injustice, extensive evidence of police violence including killings as well as beatings, framings, and unjustified arrests that continue unchecked by government authorities. They write of the challenge of enumerating state violence against Black Americans: “The vast majority of such crimes are never recorded. This widespread failure to record crimes against the Negro people is in itself an index to genocide” (Patterson Reference Patterson1951, p. 57). Their evidence was incidents of police violence from 1945 to 1951. Significant to this study, they list in their petition that on November 1, 1949, Mrs. Lena Fausset of Jamaica, New York, was beaten by policewoman Mary Shanley when she inadvertently bumped into the policewoman on the street. Mrs. Fausset, they write, was assaulted by officer Shanley in the 103rd Precinct (Patterson Reference Patterson1951, p. 113).

A Chocolate Cities Approach to Studying Police Violence

Marcus A. Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson’s (Reference Hunter and Robinson2016) “The Sociology of Urban Black America” summarizes over a century of sociological research on urban Black Americans dating back to Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s (Reference Wells-Barnett1892) Southern Horrors and W. E. B. Du Bois’ (1899) The Philadelphia Negro. Hunter and Robinson (Reference Hunter and Robinson2016) divide the extant research into ‘assets’-based and ‘deficits’-based frames of approach to the study of urban Black American life. According to the authors, the deficit frame includes scholarship emphasizing both the structures that negatively affect urban Black people and the cultural “deficits” that either are adaptations to those structural realities or, as some argue, are the cause of hardships themselves. The asset frame includes scholarship focusing on the agency and cultural contributions of urban Black Americans.

Many urban sociological studies on police violence fall under what Hunter and Robinson (Reference Hunter and Robinson2016) refer to as the deficit frame of studying Black communities. They emphasize a “ghetto” culture of crime, violence, and discontent toward police, framing the presence of police as emerging from a necessity to combat social disorder. The current study is an assets-based approach to the study of urban Black cultural responses to urban policing and police violence over time.

I emphasize the role of place and time as essential to understanding news representation of collective action in the wake of police killings, a novel approach to analysis of news discourse on police violence and officer acquittals. Newspaper reports differ on their acceptance or challenge of official police accounts of events and whether other factors, such as race, place, and age of victims played a role.

Documenting the persistence or absence of collective memory allow contextualization of contemporary political struggle in the wake of police violence. Doing so can have tremendous impact on police reform and even, in the case of the Chicago Police Department, help advocate for reparations for communities that have endured incessant harm at the hands of local law enforcement (Venkatesh et al., Reference Venkatesh, Ralph and Currie2015). Though recent research has assessed with great depth the level to which routine encounters with law enforcement shape larger attitudes about government (Lerman and Weaver, Reference Lerman and Weaver2014), focusing only on the routineness of contemporary encounters with police may miss the broader historical context necessary to fully understand collective opinions of policing.

Exploring the role of policing within predominantly Black communities is crucial to understanding the life course of the neighborhoods themselves. Existing research about policing and neighborhood context finds that police officers are more likely to use higher levels of force when encountering persons in disadvantaged and high-crime neighborhoods. This is true regardless of situational factors: whether the individual is resisting arrest, and regardless of officer training, education, or age (Terrill and Reisig, Reference Terrill and Reisig2003). Understanding the role of policing within the trajectory of a neighborhood helps us understand the purpose of policing itself, as many formerly disinvested communities become the sites of demographic change and reinvestment over time.

Data and Method

Study Setting

In considering police violence in Jamaica, Queens, it is important to understand the community itself. The Jamaica section of the borough of Queens is one of the largest historically Black communities in all of New York City. A heterogeneous community consisting of both massive public housing projects as well as middle class areas of mostly Black homeowners, the community spans class categories. Home to populations of Latinx, West Indian, West African, as well as South Asian diaspora immigrants—both from the subcontinent and the Caribbean—the neighborhood is ethnically heterogeneous as well. Located in Southeast Queens at the boundary between New York City and neighboring Nassau County on Long Island, Jamaica is one of the region’s main transit hubs for the Long Island Railroad, Metropolitan Transit Authority, and John F. Kennedy International Airport (Brown Reference Brown2005; Hauser Reference Hauser1980).

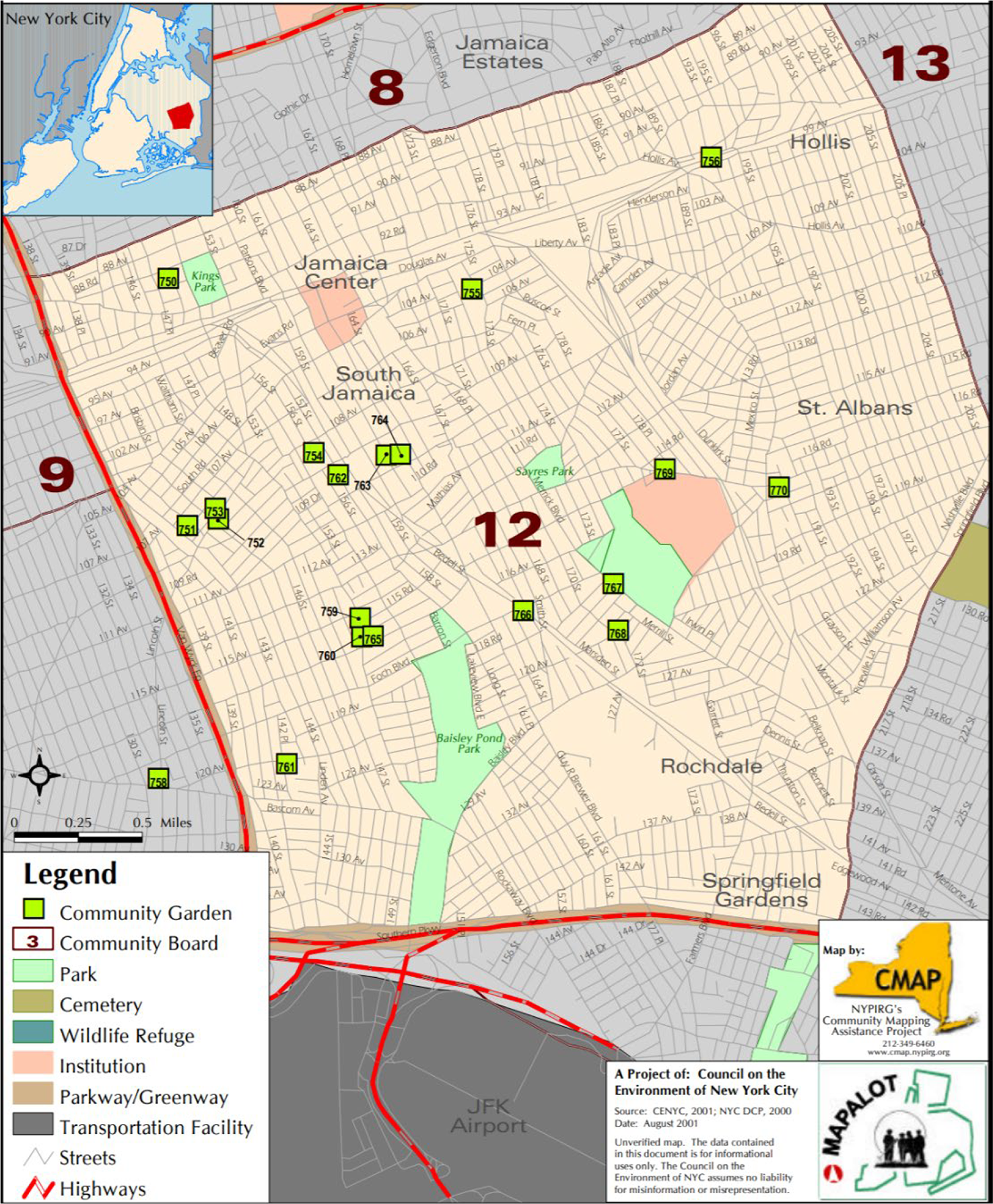

Community Board 12, shown in Figure 1, which makes up the geographic area patrolled by the New York Police Department’s 103rd and 113th Precincts, is made up of the neighborhoods of Jamaica, South Jamaica, Hollis, St. Albans, Rochdale, and Springfield Gardens. The New York Police Department’s 103rd Precinct is located on Jamaica Avenue, the center of the community’s busy commercial district. Southeast and Southwest Queens, nestled between the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn to the west and Long Island to the east, are comprised of numerous other neighborhoods: Rosedale, Cambria Heights, Laurelton, Queens Village, Ozone Park, South Ozone Park, Woodside, and Richmond Hill.

Fig. 1. Map of Community Board 12 patrolled by NYPD 103rd and 113th Precinct officers. Significant landmarks indicated. Courtesy of New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG) Community Mapping Assistance Project.

The community and the two police killings central to this study make for rich comparison. In both killings, there are commonalities beyond just their occurrence in the same neighborhood and the same precinct. First, officers in both instances were dressed in plain clothes, a practice developed by officers to maintain anonymity while conducting investigations. In 2020, the NYPD disbanded its “anti-crime” plainclothes units, because “the plainclothes units were part of an outdated policing model that too often seemed to pit officers against the communities they served, and…were involved in a disproportionate number of civilian complaints and fatal shootings by the police” according to commissioner Dermot Shea (Watkins Reference Watkins2020). Second, in both the 1973 and 2006 police killings, the claim of a gun being present at the scene was significant to officer testimonies about what occurred. Officers in both instances claimed to either see a gun or hear that someone threatened to get a gun to settle an argument, even though in both cases neither claim was sustained, and no guns were found. Policework and police power in the Jamaica, Queens community, and throughout New York City more broadly, came into question during the fallout of both the deaths of Clifford Glover and Sean Bell.

The intervening period between the killings of Clifford Glover and Sean Bell saw significant demographic, social, and economic shifts within southeast Queens communities. Specifically, after the killing of Clifford Glover in 1973, the late 1970s and 1980s saw both the rise of ethnic minority immigrant groups in the area and simultaneous concern around rising drug crime and ensuing violence. The 103rd Precinct was split into the 103rd and 113th Precincts in 1973. Today, the area policed by the 103rd and 113th NYPD Precincts is organized as Queens Community Board 12, formally referred to as the neighborhoods of Jamaica and Hollis. The population of Queens Community Board 12 is 61% Black (non-Hispanic) and 43% foreign-born. There are also significant Hispanic (17%) and Asian (11%) populations of any race.

This characteristic of the area allows for further study of an important aspect of policing and police violence: the experiences of those who are Black and foreign-born or Black ethnics. Though the present study does not specifically answer the question of how non-Black ethnic minority groups are treated by police and how this shapes subsequent attitudes toward police and racial identity, the historic study of this neighborhood furthers understandings of the impact of policing and police violence on multiethnic, multicultural Black and immigrant communities in the United States.

Around the time of Clifford Glover’s death, Southeast Queens was 90% Black and Hispanic (Hauser Reference Hauser1980). In 1973, New York City’s 103rd Precinct reported the third most felonies in the entire city, including 45% more murders than the city-wide precinct average and 167% more rapes. Only 22.6% of the reported felonies were solved. On April 2, 1973, twenty-six days before Clifford Glover was killed, a police captain named Glanvin Alveranga, the son of Jamaican immigrants, was named Commanding Officer of the 103rd Precinct, making him the first Black precinct commander in the history of Queens. At the time, Black cops made up less than 8% of the NYPD, despite Black people making up over 20% of the city’s population. The 103rd Precinct, which patrolled the largest Black section of Queens only employed thirteen Black police at the time, out of 413 total officers (Hauser Reference Hauser1980).

Any discussion of police-community relations in Jamaica, Queens in the intervening period between 1973 and 2006 is incomplete without discussion of the killing of twenty-two-year-old 103rd Precinct officer Edward Byrne in 1988. The rookie cop was guarding the house of a witness in a drug case when he was killed by men hired to carry out the assassination, making this event a national symbol of urban drug crime. Swift and punitive carceral action was mobilized through deployment of the nation’s first Tactical Narcotics Teams (T.N.T.), tasked with arresting street-level dealers en masse and deployed in Jamaica, Queens following the killing of Edward Byrne. The wave of drug arrests that followed made the community of Jamaica, Queens exemplary of the “War on Drugs.” Then-president George H.W. Bush even displayed Byrne’s badge 14072 in the White House, using the moment to advocate for aggressive and targeted policing. Forthcoming research from the author addresses these events comprehensively.

Critical Discourse Analysis

The analysis for this research draws on newspaper coverage of two police killings of unarmed Black individuals that occurred in the same neighborhood and police jurisdiction thirty-three years apart. Patrolman Thomas Shea of the New York City Police Department (NYPD) 103rd Precinct shot and killed ten-year-old Clifford Glover in 1973, and a team of NYPD 103rd Precinct officers shot and killed twenty-three-year-old Sean Bell in 2006. I use two different newspapers to analyze the narratives constructed by Black and White press media in the wake of the aforementioned officer-involved shootings. I examine coverage in The New York Times, a daily, internationally renowned, mainstream publication with the slogan “All the News That’s Fit to Print,” and the New York Amsterdam News, the oldest Black weekly publication in New York City with the slogan “The New Black View.”

These two newspaper sources were selected based on their widespread readership and influence as press media. The New York Times is the second most circulated newspaper in the United States and the New York Amsterdam News is consistently among the top five most circulated African American newspapers in the United States, though their circulation has been steadily declining (Vogt Reference Vogt, Mitchell and Holcomb2016). Previous studies have analyzed police violence using “mainstream” news sources while others have analyzed police violence comparing “mainstream” and Black news sources. This unique comparison across time within the same geographic and jurisdictional location allows for in-depth analysis of the discourse around Black individuals killed by police over time, with specific attention to the communities in which they reside.

Systematic analysis of discourse surrounding police killings of unarmed Black people entails engagement with the social theories of Michel Foucault (Reference Foucault1980), who argued that discursive practice reveals the (oppressive) social relations that are constituted in everyday social interaction. Foucault’s argument that discourse informs social relations underscores George Lakoff’s (Reference Lakoff1987) conceptual metaphor theory: metaphors provide a framework that people use to make sense of behavior, relations, objects, and people, to the point that people forget that semantic associations they created with metaphors are not natural, but conventional correspondences between one semantic domain and another.Footnote 2

The narratives about police officers, victims of police violence, and Black people in cities construct and constitute the social structures of these relations themselves. The enactment of discursive practices reaffirms ideological practices and stances (Santa Ana et al., Reference Santa Ana, Trevino, Bailey, Bodossian and de Necochea2007). To analyze newspaper data, which includes articles from both The New York Times and the New York Amsterdam News following the events of April 28, 1973, and November 25, 2006, I use the Conceptual Metaphor Theory (Lakoff and Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980; Santa Ana Reference Santa Ana2002) approach to critical discourse analysis. This approach entails line-by-line analysis of news articles, done by hand, focusing on the context (full line), token (phrase), target (subject), and source (descriptor) of each event, person, or process written about. In the case of this study, coverage revolves around the people involved in these two police killings, the trials that follow, the community at large especially during protests, and commentary on the judicial and policing processes involved. These make up the targets for which there are several sources, guiding the organization of the conceptual metaphors that arise and make up the findings of this study. See Table 2 for a sample of this coding process.

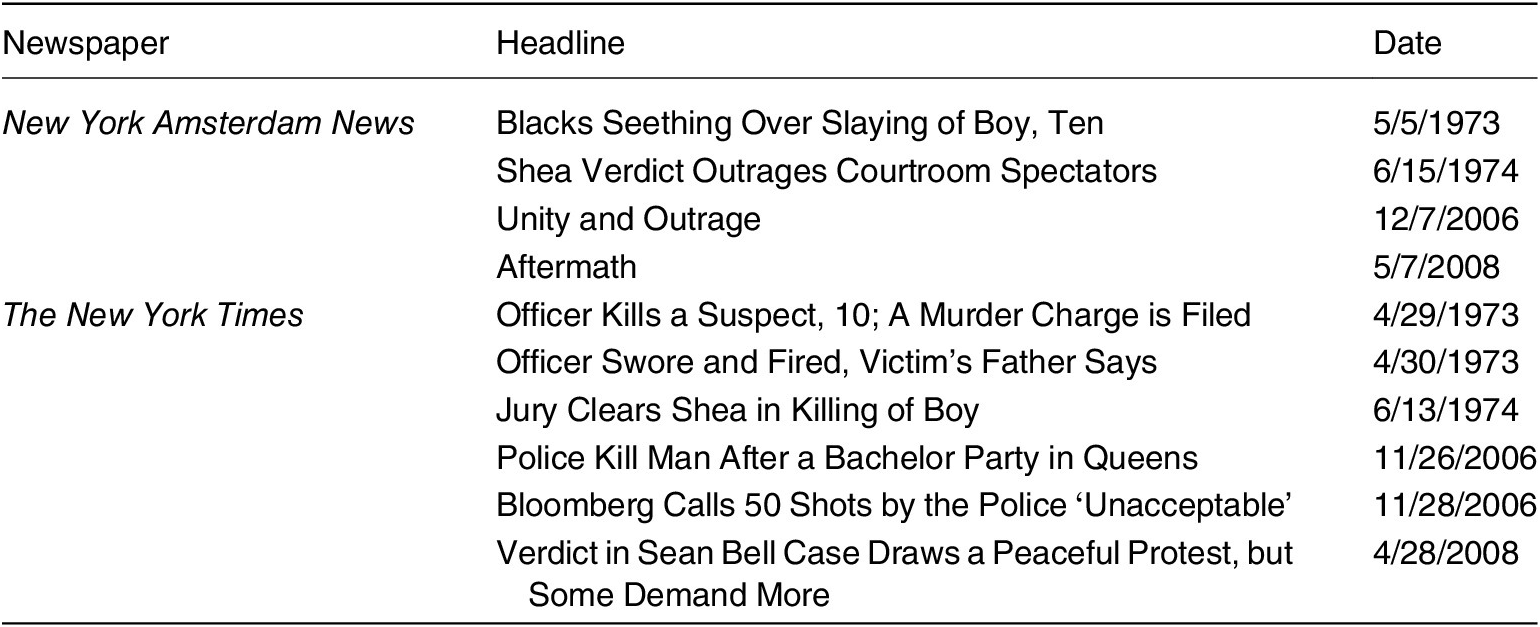

I selected and analyzed front-page articles that appeared in the issues that were published directly after the shootings and acquittals in both instances from both newspapers, totaling ten articles. All the articles are frontpage headlines and were released around the same dates, adjusted for the fact that one newspaper is daily and the other is weekly. In my representation of the data, I have added italics for emphasis on significant target phrases. Each post-killing and post-acquittal headline from both newspapers in 1973 and 2006 is listed in Table 1. Analytical attention is paid to each description and depiction of victims, officers, community residents, and politicians, both Black and otherwise.

Table 1. Data Sources: Front-page headlines from New York Amsterdam News and The New York Times, 1973-1974 and 2006-2008, post-killing and post-acquittal articles

Table 2. Sample of critical discourse analysis conducted by hand. The article analyzed is titled “Blacks Seething Over Slaying of Boy, Ten” from New York Amsterdam News, May 5, 1973.

Findings

‘No Angel’ Discourse

Clifford Glover

The study of news reporting on police violence against Black youth specifically necessitates a discussion of the dehumanization and adultification of Black children, both boys and girls. Psychologists Philip A. Goff and colleagues (Reference Goff, Jackson, Lewis Di Leone, Culotta and DiTomasso2014) find that Black boys are perceived as being more responsible for their actions and as being more appropriate targets for police violence; they are seen as older and less innocent than their White same-age peers across four studies using laboratory, field, and translational methods. Dehumanizing associations of Black boys with animals predicted actual racial disparities in police violence toward children. This is pivotal to understanding further the importance of journalistic standards and the power of media in depicting and potentially further dehumanizing/adultifying Black children who are the victims of police killings.

Following the killing of ten-year-old Clifford Glover by Patrolman Thomas Shea on April 28, 1973, in Jamaica, Queens, the first headlines released by The New York Times and New York Amsterdam News are telling in that they frame the same incident quite differently. New York Amsterdam News starts their headline by describing the state of Black people as “Seething” over “Slaying of Boy, Ten.” There is no mention of the police in this headline but one of the subheadings reads, “Wilkins Calls It A ‘Police Murder’” while another reads “His Only Fault Was Being Black.”

Meanwhile, The New York Times centers the patrolman involved, stating that “Officer” kills “Suspect, 10” and that “a murder charge is filed.” The subheading here is “Boy Was Slain During an Investigation of a Queens Taxi-Driver Robbery—P.B.A. Calls Arrest ‘Outrage’” describing Glover as a “boy” in addition to being a “suspect” who was “10” years old at the time of his death.

The New York Amsterdam News front page from May 5, 1973, features a photo of Clifford Glover dead in his coffin, eyes closed, and hands folded. The caption reads “Law and Order? TEN-YEAR-OLD CLIFFORD GLOVER RESTS IN HIS COFFIN—THE INNOCENT VICTIM OF OFFICER THOMAS SHEA.” Here, the portrayal of Clifford Glover is as a ten-year-old boy, an “innocent victim” of Officer Thomas Shea. There is an inset of Thomas Shea’s face within the same image. The image of Clifford Glover laying lifeless in an open casket invokes the memory of Emmitt Till, the fourteen-year-old boy from Chicago, Illinois who was notoriously and viciously murdered in Mississippi because a White woman lied about him, even though Till is not mentioned explicitly.

There is no such image of Clifford Glover in The New York Times front-page article released the day after his death. There is only an image of Martin Bracken, the Queens Assistant District Attorney who announced the arrest of Officer Thomas Shea.

The New York Times reports on the initial police reports of the incident, in which Clifford Glover is made out to be ‘no angel.’ This is in stark contrast to the claim of the New York Amsterdam News that “his only fault was being Black” and that he was “the innocent victim of Officer Thomas Shea,” demonstrating oppositional standpoints. The New York Times piece written on April 29, 1973 by Emanuel Perlmutter focuses on initial reports made by the policemen involved:

According to the initial police reports of the incident, the boy, Clifford Glover of 109-50 New York Boulevard, South Jamaica, had run away and pointed a gun at Officer Shea and his partner, Walter Scott, when the policemen stopped the boy and his stepfather, Add Armstead, to question them about the holdup (Perlmutter Reference Perlmutter1973, p. 1, emphasis added).

The article continues further:

Officer Shea; who the police said fired three shots at the boy, reportedly told superior officers that after the boy was shot, he had given his gun to his stepfather, who threw it into a wooded area near 112th Avenue and New York Boulevard. […] After searching the area, the police reported that no such weapon was found (Perlmutter Reference Perlmutter1973, p. 1, emphasis added).

There is no such discussion of the patrolmen’s reports of Glover ever having had a gun, pointing a gun at the officers, or giving said gun to his stepfather who supposedly threw it into a wooded area described to any extent or at any length in the New York Amsterdam News front-page article about his death.

The New York Times does not just describe Glover as having potentially engaged in criminal activity with regards to his being gunned down by policemen. He is also described as “weighing 90 pounds and standing 4 feet, 11 inches tall”, “believed to be the youngest person ever killed by a New York City police officer.” There is also reporting on how Glover is described by those who knew him: “a well-behaved youngster who attended church conducted by the Rev. Albert Johnson at a storefront at 108-34 New York Boulevard” and that “he was known as ‘a good boy’ at Public School 40, 109-20 Union Hall Street, Jamaica, where he was a pupil.”

Though these descriptions of Clifford Glover as “a well-behaved youngster” and “a good boy” may not seem to fit with the ‘no angel’ thesis, the descriptors of him as “suspect” in a taxi robbery, in addition to the suspicions of his having carried a gun, which he allegedly passed to his stepfather after being shot, certainly do. In the wake of Glover’s death, his stepfather becomes subject to scrutiny surrounding the gun that Officer Shea claimed was thrown into a wooded area nearby but was never found. Not only victims of police violence, but also their families, friends, and fellow community members, are implicated in ‘no angel’ discourse. The following evidence qualifies this claim.

On the night of Clifford Glover’s killing, his stepfather Add Armstead was arrested. The New York Times reports:

Last night, Mr. Armstead was arrested and given a summons for having an unregistered pistol in the Pilot Automotive Wrecking Company yard at 115-05 New York Boulevard, where he worked as a mechanic. The police said the weapon was not the one the officers maintained the slain boy had (Perlmutter Reference Perlmutter1973, p. 18).

The unregistered pistol found at Mr. Armstead’s place of work was uncovered because of Officer Shea’s false report that Glover handed a gun to his stepfather after he was shot, according to The New York Times. The arrest of Mr. Armstead and subsequent reporting in The New York Times depicts criminality in coordination with the police killing, even as the two are reported not to have any connection.

Further reporting in The New York Times from April 30, 1973, illuminates the ‘no angel’ thesis. Ronald Smothers wrote in the front-page article “Officer Swore and Fired, Victim’s Father Says”:

Defensiveness about his clothes was recalled by people familiar with his behavior at Public School 40, a block from his home. Clifford was in a fourth-grade class for boys with behavior problems, an acquaintance said, and ‘although he was no angel there was nothing vicious in the things he did.’ The acquaintance said Clifford often talked back to teachers and teased other students to get attention but added ‘I know he had a good heart’ (Smothers Reference Smothers1973, p. 23, emphasis added).

The article also reports on Mr. Armstead:

Police sources said yesterday that Mr. Armstead had a record of three misdemeanor arrests dating to 1965, but they had no record of their final disposition. One charge was for selling skim milk as whole milk, of which Mr. Armstead claimed no knowledge. Another was second-degree rape, for which he served four months of a six-month prison term. At that time, second-degree rape was defined by the state’s penal law as an act of sexual intercourse by a man over 21 years of age with a female under 18, not involving force. The third charge was for possession of stolen license plates, for which he served 23 days and paid a $125 fine. ‘I’ve paid my debt,’ he said (Smothers Reference Smothers1973, p. 23, emphasis added).

Mr. Armstead’s past misdemeanors and Clifford Glover’s behavior problems are reported by The New York Times two days after his death by lethal force under suspicion for a crime they did not commit. The New York Amsterdam News has no such description of Armstead’s arrests or Glover’s behavior problems in school in their coverage for the week following his death. The information reported by The New York Times provides important context on policing and criminality as well as school discipline for the time and geographic context for when and where Armstead and Glover lived. The Times also reports on why Armstead and Glover were fleeing from Officer Shea, according to police and Armstead:

Police accounts of the shooting say that 36-year-old officer Thomas Shea and his partner, both white plainclothes men, stopped Mr. Armstead and Clifford to question them about a nearby holdup of a cab driver. The two ran, the police said, and Officer Shea fired three shots, one of them hitting Clifford. As Mr. Armstead described the incident, “We were walking not saying anything to each other, and this car pulls up and this white fella opens the door with a gun. He said ‘You black son of a bitches’ and fired.’ Mr. Armstead said the man had not identified himself as a policeman. He said he had run because he had $114.82 in his pocket and was afraid that he would be robbed (Smothers Reference Smothers1973, pp. 1, 23).

Mr. Armstead’s account of the shooting differs significantly from Officer Shea’s. It is important to note what information is reported about Mr. Armstead and what information is reported about Officer Shea. Armstead’s past arrests are reported but there is no mention in articles from either newspaper that I analyzed of Officer Shea’s prior misconduct.

In March of 1972, departmental charges were filed against Officer Thomas Shea for striking the head of a fourteen-year-old Hispanic boy in Woodside, Queens twice with the butt of his gun while making an arrest. Two weeks later Officer Shea shot at a twenty-three-year-old robbery suspect twice in West Manhattan hitting him once in his neck. The suspect was indicted for attempted murder because Officer Shea claimed he fired his weapon because the suspect shot at him but no gun belonging to the suspect was found and charges against the young man were dropped (Hauser Reference Hauser1980).

Sean Bell

Following the police killing of Sean Bell, reporting from The New York Times revolved around the location of Club Kalua, where he was celebrating his “bachelor party” the night before he was supposed to be wed. The front-page article titled “Police Kill Man After a Bachelor Party in Queens” by Robert D. McFadden printed on November 26, 2006, states:

Hours before he was to be married, a man leaving his bachelor party at a strip club in Queens that was under police surveillance was shot and killed early yesterday in a hail of police bullets, witnesses and the police said (McFadden Reference McFadden2006, p. 1, emphasis added).

The article continues:

Witnesses told of chaos, screams and a barrage of gunfire near Club Kalua at 143-08 94th Avenue in Jamaica about 4:15 a.m. after Mr. Bell and his friends walked out and got into their car. Mr. Bell drove the car half a block, turned a corner and struck a black unmarked police minivan bearing several plainclothes officers. Mr. Bell’s car then backed up onto a sidewalk, hit a storefront’s rolled down protective gate and nearly struck an undercover officer before shooting forward and slamming into the police van again, the police said. In response, five police officers fired at least 50 rounds at the men’s car, a silver Nissan Altima; the bullets ripped into other cars and slammed through an apartment window near the shooting scene on Liverpool Street near 94th Avenue (McFadden Reference McFadden2006, p. 1, emphasis added).

As with the shooting of Clifford Glover, there is a police report about suspects trying to get away and the threat of force against officers involved. The officers’ claim is that Sean Bell was using the Nissan Altima that he was driving as a weapon when exiting the “strip club that was under surveillance.” This is justification on the part of the officers involved for firing fifty rounds of ammunition into the vehicle. The officers were in plainclothes and undercover, meaning they were not uniformed, as in the case of the shooting of Clifford Glover in 1973.

Reporting from The New York Times on then Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg illuminates why, according to them, NYPD officers chose to pursue Sean Bell and his friends Joseph Guzman, and Trent Benefield. The Times reports:

Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg said in a statement last night that it was too early to draw conclusions about the case. “We know that the N.Y.P.D. officers on the scene had reason to believe an altercation involving a firearm was about to happen and were trying to stop it,” he said (McFadden Reference McFadden2006, p. 1, emphasis added).

The statement that the police present expected an altercation as well as the alleged involvement of a firearm reinforces the ‘no angel’ discourse about victims of police shootings. As in the case of the shooting of Clifford Glover in 1973, a firearm was never uncovered:

Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly said at a news conference last night that the men’s car had been hit at least 21 times. He said he did not know what triggered the shooting and that it was too early to tell if it was justified. No guns were found at the scene, and no charges have been filed against the men, the police said (McFadden Reference McFadden2006, p. 1).

Later in the article, the rationale for officers’ pursuit of Bell and his friends is again clarified:

In a statement, Commissioner Kelly said that about 4 a.m. a group of men confronted a man outside the strip club and that one man in the group yelled, “Yo, get my gun” (McFadden Reference McFadden2006, p. 1, emphasis added).

In the front-page article on the killing released by The New York Times two days later, November 28, 2006, there is simultaneous reporting that the officers felt their actions were justified and that officers violated protocol:

In a move that suggests the officers feel their actions were justified, the lawyer representing the men said he had contacted Mr. Brown’s office and offered to have the officers speak to prosecutors and appear before a grand jury voluntarily without immunity (Cardwell and Chan, Reference Cardwell and Chan2006, p. 1).

Later in the same article:

Some policies appear to have been violated in the shooting, which occurred when, according to police, undercover officers fired 50 bullets at Mr. Bell’s car after he drove into one of the officers and an unmarked police van. Officers are trained to shoot no more than three bullets before pausing to reassess the situation, Mr. Kelly said in his most detailed assessment of the shooting yet. Department policy also largely prohibits officers from firing at vehicles, even when they are being used as weapons (Cardwell and Chan, Reference Cardwell and Chan2006, p. 1).

Reporting by The New York Times in the wake of the killing of Sean Bell reports on the details of the incident by offering both why police acted upon their suspicions and the ways in which they violated department protocol and policies.

The New York Amsterdam News, in contrast, reports more critically on the actions of the officers and does not offer the same depiction of Sean Bell and his friends as suspects. In their December 7 issue, under the headline “Unity and Outrage: In pursuit of justice for Sean Bell,” Nayaba Arinde reports:

On November 25, as Bell and his two friends left Club Kalua just after 4 a.m., Detective Michael Oliver in plainclothes also exited the club. He claims to have heard someone mention a gun, and then he let off 31 shots. Four colleagues joined in the shooting frenzy. When the smoke cleared, Bell was dead and Guzman, 31, and Benefield, 23, lay bleeding and handcuffed. Finding no weapon, police quickly came up with the widely questioned theory that there was a fourth man, who somehow escaped the hail of bullets, removed the alleged weapon, and got away. However, there was never any fire returned, and both Guzman and Benefield denied that there was a fourth man. Cops conducted raids, pulled up grates and were generally accused of harassing folk, conducting parallel investigations as distractions (Arinde Reference Arinde2006, p. 34).

The New York Amsterdam News here flips ‘no angel’ discourse on its head, pointing the finger of criticism and scrutiny back at the police officers involved in this case. Arinde writes scathingly of plainclothes Detective Oliver’s decision to fire his weapon thirty-one times based on his claim of hearing someone mentioning a gun. Additionally, she writes of the questionable police report of a “fourth man” who got away. Here, this imagined additional suspect at the scene is the subject or figure of ‘no angel’ discourse. Put differently, the fictitious “fourth man” is the ‘no angel’ here that is responsible for the officers’ action and retaliation. Finally, she describes cops on the case as conducting raids, pulling up grates and “harassing folk”, conducting parallel investigations to distract from the truth.

What the author and the New York Amsterdam News do here is inform the public of the parallel investigations that occur after a suspect, a Black person, is gunned down and the killing is “justified” by the potential discovery of evidence that officers then claim prompted their on-the-spot decision to enact violence. The writers for the New York Amsterdam News took a position similar to their 1973 reporting when they stated, “His only fault was being Black” a distinct departure from “He was no angel.” Their criticism of the police’s parallel investigation is absent from The New York Times reporting, positioning the two papers at odds with one another. The Times focused on the alleged criminality of Black victims of police violence, while the Amsterdam News criticized the police’s actions, explicitly naming race as the defining factor in their decisions to shoot and kill.

The Conceptual Metaphor community as disaster

Clifford Glover

Immediately following the killings of Clifford Glover and Sean Bell, their lives, and the lives of those closest to them, were placed under heavy scrutiny. Additionally, the collective action spurred by their deaths became the focus of much of the reporting of The New York Times and New York Amsterdam News. Reporting from the New York Amsterdam News, immediately following the death of Clifford Glover by gunshots from 103rd Precinct Officer Thomas Shea, made several references to the Black community, both in Queens and throughout New York City. Here we see the emergence of the conceptual metaphor community as disaster where terminology used to describe Black people and majority-Black communities in the wake of police violence mirrors that which describes volcanoes, earthquakes, and other natural disasters:

Blacks seething over slaying of boy.

In a show of unity seldom seen since the stirring “Sixties”, Blacks in Manhattan joined hands with Blacks in Brooklyn and Queens to register a seething protest over the fatal shooting of a ten-year-old Black boy.

Although the protest began in an angry, but orderly fashion, it erupted in violence, the most violent eruption coming Tuesday night. The scattered violence centered in the vicinity of New York Boulevard in South Jamaica (New York Amsterdam News 1973a, p. A1, emphasis added).

This reporting of disaster in the New York Amsterdam News continues after the acquittal of Officer Shea, found not guilty of murder or of manslaughter in the death of Clifford Glover. They report:

Following the shooting last summer, angry community residents went on the rampage breaking store windows and staging a demonstration at the 103rd Precinct.

“I hate to think of what will happen if Shea is acquitted,” said a community worker of Jamaica who never missed a day of the trial. “It can be a very explosive situation. Shea is well known in the community for what he is and the people of the community know he’s guilty” (Todd Reference Todd1974, p. A1, emphasis added).

After Shea’s acquittal, The New York Times reported on the same protests that followed the killing of ten-year-old Clifford Glover the year prior. They racialize the collective action taken by New Yorkers in the wake of the tragedy:

The shooting by the white officer of young Glover, who was black, touched off several days of disturbances in the poor and predominantly black community of South Jamaica. But the only organized protest at the courthouse yesterday was a line of about 20 pickets, with whites outnumbering blacks. One of the signs said: “A shield is not a license to murder children” (Johnston Reference Johnston1974, p. 27, emphasis added).

The article contrasts the “disturbances” that took place in “poor and predominantly black” South Jamaica with the “only organized protest” at the courthouse, which was characterized by “whites outnumbering blacks.” Here, then, there is the association of collective action in poor Black communities as “disturbances” that are disorganized in comparison to the “only organized protest” which was majority White. The subheading for the section directly after this quote is titled: “Community Braced” furthering the community as disaster metaphor. The plan of caution, in preparation to brace for the anticipated disaster and chaos to come, is described:

Last night in South Jamaica, in the New York Boulevard section where the shooting took place, leaders of the black community assigned 20 staff members of the Central Queens Association, the community corporation, to patrol the area in cars and jointly arranged with Queens police headquarters to have another staff member available to accompany the police in patrol cars, if necessary. “The community feels shock, anger and a sense of a miscarriage of justice,” said James Heyliger, a spokesman for the association. “Youth gangs and other people, too, will be upset over what they consider a sellout by community leadership—a decision to trust to the trial, even after the basically white middle-class jury was selected, even though the average people never had any faith in it” (Johnston Reference Johnston1974, p. 27, emphasis added).

Sean Bell

Following the killing of Sean Bell in 2006, the New York Amsterdam News recalled the shooting of Amadou Diallo by NYPD officers seven years prior:

This last fortnight has been reminiscent of a city all fired up in the wake of the 1999 41-shot police barrage which left Amadou Diallo with 19 hits to the body and an international incident on the record (Arinde Reference Arinde2006, p. 34, emphasis added).

Later, in the same article, reference is made to the community being on edge, close to the brink of chaos, destruction, disaster:

“Our community is getting close to a tipping point,” said Councilman Charles Barron. “People are sick and tired of the inadequate response to the continued murder of our young men at the hands of New York City police officers” (Arinde Reference Arinde2006, p. 34, emphasis added).

Reporting from The New York Times on the meeting between Mayor Bloomberg and Black leadership from around the city held immediately after Bell’s death illuminates the metaphor further:

Although several of the leaders at City Hall expressed confidence in the mayor and the police commissioner, the emotional meeting, which began with outbursts of anger and ended calmly, laid bare some of the rifts among New York’s black leaders themselves. Many, however, expressed concerns that the administration was failing to deal with what they described as continuing tensions between black residents and police officers even when the officers are not white. “There were some heated exchanges,” said the Rev. Herbert Daughtry, an influential Pentecostal minister in Brooklyn. “We all agree that there is a pattern of police abuse of power, and this abuse of power ranges from police killing to police brutal behavior to disrespect. We reiterated that over and over again.” Mr. Daughtry warned the mayor not to confuse patience with complacency. “There is a temperature in our communities that is rising, and the tension is intensifying,” he said. “While we don’t want to try to ignite anything, we’d be blind to overlook what’s happening and not to sound the alarm” (Cardwell and Chan, Reference Cardwell and Chan2006, p. B4, emphasis added).

The conceptual metaphor community as disaster is employed by Rev. Daughtry to explain the severity of the situation. His account of the meeting is that “we all agree” about “a pattern of police abuse of power” ranging from “police killing to police brutal behavior to disrespect” and that those points were reiterated during the meeting with the mayor repeatedly. Daughtry’s understanding of the problem not only with police killings, but also with policing in New York’s Black communities generally, is underscored by his warning to not confuse “patience with complacency.” The concern here then is the community erupting once again. The disaster conceptualized as earthquake, volcano, or wildfire, is a Black community that has grown impatient and fed up with police violence, ignited by police killing.

After the trial and acquittal of all officers involved in the fatal police shooting of Sean Bell, The New York Times focused on how peaceful the protests were in comparison to collective action in response to prior police shootings:

Unlike some previous verdicts in police shootings, the acquittals in the Bell case have so far been largely met with a muted response. Thousands of protesters did not fill the streets, no unrest ensued.

At a news conference at the Harlem headquarters of the Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network, Mr. Sharpton and other activists, politicians and community leaders praised the overall peaceful response that followed the verdict, and vowed to fight the judge’s decision in strategic rather than bellicose ways.

“Some in the media seemed disappointed, they wanted us to play into the hoodlum, thug stereotypes,” Mr. Sharpton said. “We can be angry without being mad.” And while many onlookers shouted their support, others admitted restlessness and a yearning for something more. But Nkrumah Pierre, a banker who lives on Long Island and who marched in the protest on Sunday, said: “We’ve progressed to the point where we don’t need to act out in violence. This is an intelligent protest, and a strategic protest” (Buckley and Lueck, Reference Buckley and Lueck2008, p. B3, emphasis added).

The New York Times reports on the type of protest undergone by Black community members following the police killing of Sean Bell as contrasting with community as disaster discourse, positioning the protests as having progressed to a point of more “intelligent” and “strategic” action.

After the trial and acquittal of all officers involved in the fatal shooting of Sean Bell, the New York Amsterdam News evoked community as disaster with their headline in all caps: “AFTERMATH: New York City reacts to Sean Bell verdict.” While White Press, in this study, focuses on interviewing Black individuals considered to be leadership and authority figures, much of this article centers around Black people’s call to “shut the city down!” bringing up various reactions from interviewed individuals, including a far wider variety of political opinion from Black residents, from gang members to artists to businesspeople to clergy.:

The initial community reaction to the police acquittals in the killing of Sean Bell on his wedding day, November 25, 2006, has been more than predictable: anger, frustration and disgust. From initial shock to a grassroots call for a complete economic boycott on Saturday, May 3. “I’m not surprised by the verdict at all,” said Bomani of rap group United Front. “I’m just surprised and hurt by the reaction of the people: that New York did not get torn to the ground” (Arinde Reference Arinde2008, p. 1, emphasis added).

The article continues reporting on Bomani’s contrast between New York being torn down with New York being shut down, delineating the difference between violent protest and economic boycott:

Last year, United Front recorded the powerful and controversial album “50 shots for Sean Bell.” This week, the Brooklyn-Harlem duo is part of a movement calling for a dollar-free Saturday. Bomani stated, “We are shutting down New York City on Saturday, May 3 for Sean Bell. We urge all [Black and Latinos] not to spend a single dime anywhere in New York city. No gas, no food, no cloth” (Arinde Reference Arinde2008, p. 1, emphasis added).

The Amsterdam News further reported on the tension between different forms of collective action in the wake of police killings and officer acquittals:

“I’m outraged at a blatant abdication of justice,” Queens Council Member James Sanders told the AmNews. Bell was, and Guzman is, his constituent, said the city legislator. “The community is outraged: we feel that there was never an attempt to bring justice here. My personal view was that the strategy our New York City community of justice seekers had was not holistic. We did not take it to the streets. We were told if we raised our voices, if we showed our resolve, that they may take this trial away from us. We allowed them to set the pace and the path—and we followed it to our detriment. We need to take this back to the street and have a holistic approach, a legal approach, a mobilization approach—and all of us work in harmony” (Arinde Reference Arinde2008, p. 1, emphasis added).

Council Member Charles Barron’s statement on the state of Black communities in New York following the bench trial and acquittal elaborates the conundrum of peacefully complying with the justice system, from police killing to bench trial and acquittal:

Brooklyn City Council Member Charles Barron asserted, “There’s no legal rationale for what Judge Cooperman did. He was obviously a pro-cop judge and had no intention of convicting the three defendants. By talking about the victims the way he did, by talking about the demeanor of the witnesses, and about the lawsuit—which they do have a right to file—he showed his obvious disdain.” Barron slammed the prosecution as ineffective. “This is why Marq Claxton from 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement and myself called for a special prosecutor from the beginning. They have said to us that they haven’t got past Dred Scot. It is incumbent on us to protect ourselves by any means necessary. We have the God-given and constitutional right to do that. Alton Maddox has said over the years that they should abolish bench trials. When police officers kill innocent civilians, as public servants they should be forced to face a public jury—not just a judge. Right after Sean Bell, 6 Black men died at the hands of police—they have not eased up during the duration of this trial. “If young people rise up or do what they need to in order to protect themselves from killer cops sanctioned by the system to kill them with impunity—what would you tell them? Because they are now target practice, and it is open season on them: Amadou Diallo—41 bullets. Sean Bell—50 bullets. What is the appropriate response? We are looking at creating a Malcolm-King Community Patrol to prevent police and community violence. You’ve got to stop the criminals in blue jeans and the ones in blue uniforms” (Arinde Reference Arinde2008, p. 31, emphasis added).

Barron states that cops killing with impunity are the source of young people “rising up.” Young people, he declares, are doing what they need to in order to protect themselves from “killer cops”, a “God-given and constitutional right.” Councilman Barron advocates for the abolition of bench trials and a Malcolm-King Community Patrol to prevent police and community violence. In retrospect, Barron’s warning that disaster was pending was a premonition.

The conceptual metaphor community as disaster is utilized in discourse by political leadership and reproduced by news and other media coverage in the wake of police killings. In response to the use of lethal force by 103rd Precinct police officers in both 1973 and in 2006, and then after the ensuing officer acquittals—in trial by jury in 1974, and by bench trial in 2008—narratives of urban disorder and social unrest are propagated. The fear is that Black communities will rebel once again, as has happened in the past, and that this upsets the collective social status quo and police power will once again be scrutinized. This fear is discussed by both newspapers and explains the relationship between policing, news, and rebellion in segregated metropolises.

The Loss of Memory

Central to this project’s conceptualization of memory is the theoretical framework of colonial aphasia. Writing about disabled, or deadened, racial histories in France, Ann Laura Stoler (Reference Stoler2011) coined the phrase to better describe and define what often is referred to as “forgotten history” or “collective amnesia.” Describing the active process of making colonial legacies unavailable, she writes:

But forgetting and amnesia are misleading terms to describe this guarded separation and the procedures that produced it. Aphasia, I propose, is perhaps a more apt term, one that captures not only the nature of that blockage but also the feature of loss…It is not a matter of ignorance or absence. Aphasia is a dismembering, a difficulty speaking, a difficulty generating a vocabulary that associates appropriate words and concepts with appropriate things. Aphasia in its many forms describes a difficulty retrieving both conceptual and lexical vocabularies and, most important, a difficulty comprehending what is spoken (Stoler Reference Stoler2011, p. 125).

Enabling racial histories that have been disabled requires looking into the documented representation of those histories themselves. Specifically, the ways that police violence operates in Black communities and is depicted and reported reveals the ways they are thought of and then acted upon through policy.