In 1672, the Dutch Republic seemed on the brink of collapse. For more than a century since its successful revolt against Habsburg Spain, the Dutch Republic had successfully defended its borders against foreign invasion and built a Golden Age of security and prosperity. Disaster struck when the combined forces of Louis XIV of France, King Charles II of England, and the prince-bishops of Münster and Cologne declared war on the Republic in spring 1672. The bishop of Cologne attacked from the east, while the bishop of Münster laid siege to the northern Dutch city of Groningen. A combined Anglo-French fleet attacked from the sea, choking off ports and trade. The French king invaded from the south with a force of over 130,000 men, four times the number of Dutch defenders. His army quickly overwhelmed Dutch defenses in the borderlands, conquering the less-populated eastern provinces and much of Limburg. By June, French forces swept into the heart of the Republic intent on capturing the large, prosperous city of Utrecht. “So desperate and in such confusion” were its city leaders that they capitulated without a fightFootnote 1 (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. The Rampjaar of 1672. The water lines (dark grey) were critical defenses against the invading forces of Louis XIV of France and the bishops of Cologne and Münster. Hashed grey areas indicate occupied territories. Water line boundaries adapted from Gottschalk, Stormvloeden, 236, 240, 247.

In response to the shocking speed of the invasion, the provincial assembly of Holland (called the Estates of Holland) ordered the countryside flooded to halt the enemy advance, essentially conceding the eastern half of the country.Footnote 2 These strategic inundations would stretch from the Southern Sea (Zuiderzee) northeast of Amsterdam to the Merwede River in southern Holland. The Dutch had institutionalized this tactic in the sixteenth century during the defense of the Northern Netherlands from Spanish forces. River and polder dikes in several provinces could be breached, providing multiple layers of protection.Footnote 3 The “Holland water line” (Hollandse waterlinie) protected the wealthiest and most populous province of the Republic. Inundation, ordinarily an enemy, seemed in 1672 a potential ally. Unfortunately, the preceding months of drought reduced available river water, limiting its effectiveness.Footnote 4

By mid-summer, the stunning success of the enemy advance prompted widespread social and political unrest in Dutch cities. An angry mob violently unseated Holland’s chief statesman, the Grand Pensionary (raadpensionaris) Johan de Witt, later killing him and his brother. Burghers rioted in cities across the Netherlands, looting houses and attacking the regents they deemed responsible for the defeats. By August, the Dutch Republic had lost its leadership and two-thirds of its land area. The Dutch refer to 1672 as the “Disaster Year” (Rampjaar) – an appropriate encapsulation of this calamitous moment of social and political upheaval. Historians often characterize the Dutch Republic’s geopolitical situation during the Rampjaar as radeloos (desperate), their government as redeloos (irrational), and the country itself reddeloos (irretrievable).Footnote 5 The Rampjaar represented a crisis of dramatic and revolutionary consequence.

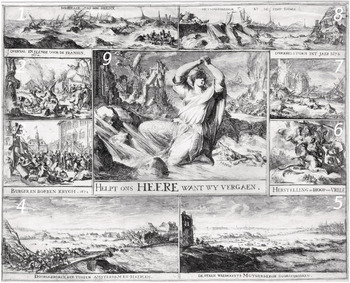

Few artists captured the climate of anxiety and helplessness during the Rampjaar as powerfully as Romeyn de Hooghe. The remarkably active artist produced over two dozen etchings of the invasion and its aftermath.Footnote 6 His print “Miserable Cries of the Sorrowful Netherlands” (Ellenden klacht van het bedroefde Nederlandt) is among the most striking examples. It presents a frenzied vision of calamity (Figure 1.2). The central female figure in panel nine symbolizes the Republic. She clasps her hands in desperation, surrounded by images of wartime atrocities and social unrest. Panel two depicts the invasion of the French army and the subsequent “misery” inflicted on the Dutch populace. Below in panel three, De Hooghe illustrates the “civilian and farmer struggle” (Borger- en boeren-krijgh) that followed the invasion, which pitted “the rich against the rich, the holy against the holy, everyone against each other.” These scenes move the viewer though the opening months of the invasion into its darkest moments of social turmoil.Footnote 7

Figure 1.2. This image depicts the disastrous events of the period between 1672 and 1675, here unified into a period of disaster. 1. Dike breach at Den Helder (1675); 2. Pillaging of the invading French Army (1672); 3. Citizen uprising (1672); 4. Dike breach between Amsterdam and Haarlem (1675); 5. Dike breach at Muiderberg (1675); 6. Restoration and hope of peace with William III (1672); 7. Windstorm in Utrecht (1674); 8. Dike breach at Hoorn (1675); 9. Floods, warfare, and windstorms surround the maid of Holland.

Ellenden klacht’s purpose extended beyond documenting social and political disorder, however. De Hooghe dedicated most of the space in this print to natural disasters. Floods and storms swirl around the central figure, and framing images depict broken dikes and buildings toppled by storm winds. Panel seven on the right depicts the windstorm (dwarrelstorm) that destroyed part of the Cathedral of Utrecht (Domkerk) in 1674.Footnote 8 Panels one, four, five, and eight depict inundations during the Second All Saints’ Day Flood (Tweede Allerheiligenvloed) that occurred near Amsterdam and in the north of Holland, a region called West Friesland and the Northern Quarter.Footnote 9 De Hooghe downplays any distinction between these localized “natural” disasters and catastrophes resulting from social or military disorder. The Rampjaar was a hybrid phenomenon of national significance. He also condenses time, visually merging calamities that occurred across multiple years. De Hooghe’s Rampjaar stretched from the invasion of 1672 to the floods of 1675. His portrayal of nature’s violence mirrored social and military devastation, underlining the interconnectedness both he and his contemporaries found between natural and social disasters. Once again, the central panel underscores this point. The broken staff of the god Mercury represents wealth and lies at the feet of the central figure, the Domkerk crumbles behind her, the inscriptions “poverty” (armoe) and “decay of commerce” (neeringloosheid) swirl in the floodwaters around her feet. The large central inscription underscores the figure’s distress, giving voice to the gravity of this collective misfortune. “Help us Lord,” she pleads, “because we perish.”

De Hooghe’s Ellenden klacht so effectively captures the relationship between natural disaster and Dutch decline in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century because it conveys two seemingly contradictory narratives. The first centers on the drama, chaos, and terror of 1672. It connects this moment of trauma with social disorder and natural disasters that continued years after the military outcomes concluded. From this perspective, the Rampjaar did not end in 1673, nor were its hazards limited to foreign armies or unruly burghers. Water and wind proved equally dangerous foes. Contemporary disaster commentary had long found political, social, and moral meaning in natural disasters, but the Rampjaar seemed different because its threats appeared so transparently existential. The print clearly expresses this new condition. It contrasts the historic, blessed condition of the Netherlands with ongoing social and natural disasters of 1672–75. The accompanying text gives voice to the personified Netherlands. “I was an arbiter of crowns, the darling of prosperity, a mirror of the world,” it proclaims, “now heaven, earth, and sea rise up against me.”Footnote 10 De Hooghe’s depiction of the Rampjaar resonated with viewers because the scenes of destruction were such a reversal of fortune. The Golden Age of wealth and security seemed past. In this light, it is easy to see why observers might read this image as commentary on Dutch decline.

At the same time, Ellenden klacht subverts this declensionist message. Despite its many visual cues to the contrary, this document remains optimistic. It embraces disaster as a trial of faith (beproeving) and projects confidence about the future. Indeed, cultural historian Simon Schama argues that this type of optimism became a “formative part” of Dutch Golden Age culture.Footnote 11 “Take heart in her disasters,” the text resolutely declares, “[s]he [the Dutch Republic] moves her hands and make right the hardship, saves her commerce and best polders, and she will have power enough left to force her enemies to a fair peace.”Footnote 12 She reassures her audience that the disasters of the 1670s are merely temporary hardships, not indicative of God’s lasting disfavor. The final line of Ellenden klacht quotes Virgil and underscores this optimistic Golden Age mentality. “O Passi graviora dabit Deus his quoque finem.” (O friends and fellow sufferers, who have sustained severer ills than these, to these, too, God will grant a happy period.)Footnote 13 According to this alternate reading, the central figure is not wrenching her hands in fear so much as she is extending them heavenward in a prayer of submission. Ellenden klacht vividly displays the shock and trauma of the Rampjaar, but its underlying message is one of piety and resilience. Calamity and perseverance, both themes apparent in De Hooghe’s print, defined the Dutch eighteenth century as the brilliance of the Golden Age faded.

1.1 Prelude to Disaster

Disasters reflect the environments and societies that produce them. On the eve of the crisis in 1672, the Dutch Republic was already a society in transition. The conclusion of its eighty-year-long revolt against Habsburg Spain in 1648 confirmed the Republic as a major political power and the commercial and financial center of Europe. For much of the previous century, the Republic had prospered due to its unique synergy of urban growth, maritime trade, and highly commercialized agriculture and fishing. The roots of these developments were regionally diverse and began long before the founding of the Republic, but they accelerated between the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.Footnote 14 Waves of immigration, driven by warfare and religious persecution or enticed by opportunity, swelled Dutch towns and cities and provided capital, labor, and connections instrumental to the expansion of Dutch industry and overseas trade.Footnote 15 The most dynamic changes occurred in low-lying maritime areas of the country, especially the many cities and towns of Holland. In the western countryside, urban capital, high agricultural prices, new drainage technologies, and a complex system of local and regional water management institutions transformed the bogs and peat lakes of low-lying coastal regions into productive commercial farms.Footnote 16 Foreign visitors marveled at the Dutch capacity to transform these landscapes and also the “miracle” of economic growth driven by Dutch overseas commerce. “By Meanes of their shipping,” one English author noted in 1640, “they are plentifully suplied with whatt the earth affoards For the use of Man … with which supplying other Countries, they More and More enritche their owne [sic].”Footnote 17 The shipping and re-shipping of “bulk” trade items such as Baltic grain, North Sea herring, and later “luxury” goods from Asia, Africa, and the Americas integrated Dutch ports into an emerging global economy with Amsterdam at its center. By the third quarter of the seventeenth century, the Republic had become a dominant force in world commerce.Footnote 18

During the 1650s, important elements of this picture began to change. This was partly the result of changing geopolitics. Scarcely four years removed from the Peace of Münster that ended the Eighty Years’ War, the Republic again found itself embroiled in conflict, this time the result of commercial competition and festering political and ideological tensions with England. The Republic fought two Anglo-Dutch Wars (1652–54, 1665–7) to protect their interests prior to 1672. Although the Dutch maintained their position as a major political and military power throughout the seventeenth century, the cost of war and rising tide of protectionist trade policies during this era was immense.Footnote 19

Perhaps the most fundamental shift occurred in the countryside, which experienced a century-long slump in agricultural prices beginning in the 1660s. In the context of this secular trend, agricultural revenue declined even as water management and labor costs increased.Footnote 20 The close connection between overseas trade and agricultural exports ensured the broad impact of these changes, especially in Holland. Economic inequalities, present during periods of explosive growth, increased.Footnote 21 The economic picture was far from grim, however. The West India Company would soon lose its colonial grip on Brazil and New Netherland, but the Dutch Atlantic economy expanded. The luxury trades continued to flourish as the VOC expanded its influence in the East Indies and Southern Africa. These gains often exacted a brutal human cost, especially as Dutch participation in the Atlantic and Asian slave trades expanded after midcentury. Closer to home, export-oriented industry diversified, populations grew in most areas of the Republic, and urbanization in many of its largest cities continued. Amsterdam became a city of 200,000 people by 1672. It was a bustling, cosmopolitan city and symbol of the Republic’s continued dynamism. Although some historians would retrospectively point to the mid-seventeenth century as its economic high watermark, in the estimation of many contemporaries at home and abroad on the eve of invasion, the Republic was experiencing a Golden Age.Footnote 22

The period between 1650 and 1672 also featured dramatic cultural and political change. The Reformed (Calvinist) faith enjoyed a position of privilege as the public Church and victory over the Spanish seemed confirmation that the United Provinces enjoyed divine favor. Devout Calvinists fashioned these beliefs into a self-image of the Republic as a second “Israel.”Footnote 23 After midcentury, the Further Reformation – a movement within Dutch Pietism that called for the purification of the Church and society and a deepening of personal morality – gained influence as well. This notion of the Dutch as a chosen people in an imperfect relationship with God would remain an important cultural framework to interpret disasters in the eighteenth century.

Despite the power of the Reformed Church, the decentralized character of Dutch governance fostered religious pluriformity and a high degree of tolerance by European standards. Confessional conflicts nevertheless remained subjects of intense theological and political debate.Footnote 24 Although the peace celebrations following the Treaty of Münster encouraged conciliation between these groups and promised a new age of concord, many of the internal social and religious divisions within the Republic hardened soon thereafter.Footnote 25 These conflicts served up consistent challenges for the state, which likewise navigated tensions between its cities and provinces.Footnote 26 Particularism was embedded in every level of governance, from foreign affairs to water management. During disasters, the decentralized, pluralistic character of Dutch society and culture meant that the highest level of state involvement often resided with the provinces, but regional and city interests weighed heavily on disaster response as well.

On the scale of the Republic at large, political conflict also arose out of the contradictory ambitions of its two most powerful players: Holland and the House of Orange. Relative to other provinces, Holland was first among equals by virtue of its wealth, sizeable urban population, and disproportionate share of tax responsibility. The Princes of Orange, meanwhile, exerted considerable influence in Dutch politics based on their claims as governors (stadhouder) of provinces. Stadhouders traditionally commanded the Dutch Army during wartime. William (“the Silent”) of Orange had led the Dutch Revolt and his descendants commanded Dutch forces throughout the eighty-year-long conflict with Spain. During this period, the balance of power between the Princes and Holland had waxed and waned but reached a new inflection point in 1650 when William II staged a coup that failed after he died of smallpox. This left the Republic without a unitary stadhouder. The province of Holland, under Johan de Witt, capitalized on this opportunity to assert Holland’s dominance in political affairs and culture and institute what his republican allies labeled an era of “True Freedom.” This “first stadhouderless period” continued until the Rampjaar in 1672.Footnote 27

The dynamic environmental conditions of the third quarter of the seventeenth century added yet another layer of complexity to this changing social and political landscape. The diverse physical geography of the Republic was heavily influenced by water, whether the North Sea along its northern and western borders or large European rivers such as the Rhine, Meuse, and Scheldt that bounded and bifurcated the country. These fluid elements modified highly erodible peat and sandy soils, producing a diverse and variegated landscape. Long-term human interaction with these physical features, whether via agriculture, peat extraction, drainage, or canal building, produced intensively managed cultural landscapes. These processes were already well under way in the Middle Ages, though the degree and character of influence varied sharply by region.Footnote 28 By the mid-seventeenth century, the Dutch had manufactured cityscapes and landscapes highly tailored to their needs through a combination of technological, social, and institutional ingenuity.

These efforts to harness nature yielded considerable rewards, but also presented unforeseen problems. Many of the most serious and persistent challenges resulted from the management of water. Centuries of embankment, sedimentation, and storm surges shifted the distribution of river water along the main branches of the Rhine, which created problems in the Dutch riverlands for flood defense, navigation, and settlement. Further intervention accelerated sedimentation and the silting up of river mouths and harbors. Drainage-induced subsidence and peat extraction for energy lowered the level of the land relative to rivers, lakes, and seas. Each of these conditions influenced the frequency and severity of flooding.Footnote 29 Dredging harbors, draining or pumping excess water, and building and maintaining flood infrastructure mitigated some of these risks but exacerbated others. Once begun, labor and capital-intensive water management necessitated continuous, costly investment. These costs, combined with rising inequality and inflexible water management institutions, meant that flood vulnerability grew in many areas of the Republic throughout this era.Footnote 30

Climate change presented another important environmental influence during the mid-seventeenth century. Beginning in the 1640s, the climate of northwest Europe entered the “Maunder Minimum” – a low point in solar output and one of four great cooling phases of the Little Ice Age. The term “Little Ice Age” refers to a period between approximately 1300 and 1850 when average annual temperatures around much of the world declined. Within this general trend, significant variation took place and even included periods of remarkable warmth.Footnote 31 Expressions of climate varied dramatically by region and shifted in the medium and short term, due in part to natural oscillations in atmospheric and oceanic circulation, volcanic eruptions, fluctuating solar radiation, and possibly land use change.Footnote 32 Beyond temperature, historical climatologists have linked the Little Ice Age conditions to regional changes in average precipitation, wind speed and direction, and storminess.Footnote 33 In the northern hemisphere, the most pronounced cooling occurred during the Grindelwald Fluctuation (1560–1628) and the Maunder Minimum (1645–1720). As the Dutch entered the second half of the seventeenth century, therefore, climate was again shifting. Despite intense variability, average winter temperatures in northwest Europe declined, summers grew wetter, and storminess likely increased.Footnote 34

This evolving climate brought weather that impacted Dutch society in multiple and complex ways, which complicates efforts to connect them to discrete disaster events. Climate changes played out over decades or centuries. Within longer climatic trends, annual and seasonal weather varied intensely, especially during the coldest periods of the Little Ice Age. Scholars thus construct causal claims that relate shared human experiences to similar weather events, whether the prevalence of subsistence crises during years of shortened growing seasons, epizootics following wet summers and cold winters, or the likelihood of flooding during periods of elevated storminess.Footnote 35 The contingent nature of social response to weather and extreme events means that many conclusions must be couched in the language of probability.Footnote 36 Human decisions, technologies, and institutions likewise conditioned disaster impacts. Climate was important but by no means the only variable in play.

Complicating matters further, the experience of weather was always filtered through the lens of perception, prior experience, and underlying social and economic vulnerabilities. These factors influenced the interpretation of events, subsequent outcomes, and the likelihood they would be recorded. Extreme events like storm surges, river flooding, and extreme winters produced far more documentation than relatively benign conditions.Footnote 37 Despite these challenges, scholars have developed robust and nuanced strategies to parse the relationship between climate, weather, and human history.Footnote 38 Historians and historical climatologists have demonstrated that across large regions of the world, climate change during the coldest and most erratic periods of the Little Ice Age increased the likelihood of harvest failures, epidemics, and other disasters. In combination with a variety of other factors, this contributed to widespread violence, social unrest, and political instability. Some of the worst impacts in Europe occurred during the Maunder Minimum, which encompassed the period leading up to 1672.Footnote 39

The Dutch experience of climate change during the Maunder Minimum was no less complex than in other territories, yet compared to its many neighbors struggling amidst adversity, the Dutch enjoyed relative stability and strong economic growth.Footnote 40 Recent research by historian Dagomar Degroot has demonstrated that, relative to other European powers, Little Ice Age conditions presented more benefits than disadvantages to the Republic. The reasons were multifaceted – and included the Dutch capacity to capitalize on the circulation of people, goods, and information – to tap energy sources such as wind and, in some cases, avoid the worst consequences of disaster experienced elsewhere.Footnote 41 The Dutch Republic was certainly not immune to environmental setbacks during this era, including natural disasters. Communities continued to experience epidemics in cities and the countryside, devastating coastal and river floods, and harvest failures. The uneven consequences of these disasters demonstrated that environmental conditions, including climate change, rarely determined outcomes; rather, they worked through a suite of social, economic, and political structures that likewise remained in flux.Footnote 42 As temperatures descended into a new nadir in the 1650s that would last through the invasion of 1672, changing environmental conditions would again yield benefits, but also challenges for the Republic.

To later critics and historians of the Republic searching for signs of waning influence and prosperity, the second half of the seventeenth century presented a clouded picture. The many economic, political, and environmental changes of the era produced little in the way of absolute rupture, but their influence would gradually reshape Dutch culture and society. On their own, none determined the course of later events, yet each exerted an important influence. The interconnection between these structural changes in society and environment, not to mention the influence of culture and individual decisions are difficult to parse for historians and would have been virtually impossible for contemporaries. During and following disasters such as the Rampjaar, however, greater degrees of this complexity gained definition. The richness of written and visual disaster documentation and the tendency of contemporaries to self-assess, critique, and reflect on the meaning of calamities present ideal opportunities to reconstruct these relationships and serve as a reminder that perception governed interpretation and response. The trauma of the Rampjaar and its attendant social and natural disasters presented one such moment of heightened awareness.

1.2 The Rampjaar and the Beginning of Dutch Decline

The Rampjaar sparked a profound reaction in Dutch society and culture. The trials of that year fundamentally altered the status quo, and their consequences reverberated across subsequent decades. “Who ever lived in more remarkable times,” one pamphleteer remarked in 1672, “when were there ever days with as much change as ours?”Footnote 43 As with disasters before and since, opportunists welcomed them as moments of creative destruction. De Hooghe’s Ellenden klacht again provides valuable insight. In panel six, he depicts the “restoration and hope of peace” signaling the return of civic order and promise of victory under the leadership of William III. As head of the House of Orange and grandson of William the Silent, William III took advantage of the power vacuum created upon the death of Johan de Witt. By early July 1672, the powerful maritime provinces of Zeeland and Holland installed William as head of the military and stadhouder. This changing of the guard was indicative of a larger shift in political power away from the regents of Holland to the supporters of the House of Orange that would last until William’s death in 1702. For De Hooghe, who was himself an “Orangist” (supporter of William III), this panel conveyed a significant, albeit visually subordinate, message. The print is an apologist political statement favoring the return of the House of Orange to a position of political primacy and the end of the first stadhouder-less period. Although the dominant visual motif for the print is tragedy, the “restoration and hope of peace” reminds the viewer that disasters are always in the eye of the beholder. A catastrophe for some may yield opportunities for others.Footnote 44

From a military perspective, glimmers of hope appeared by the late summer of 1672. Dutch armies followed naval victories against the British with the lifting of the siege of Groningen and the recapturing of large parts of the eastern Republic. Even the weather seemed to shift in favor of Dutch defenders. The drought conditions that prevailed in the early months of 1672 had been atypical of the Maunder Minimum, which tended to feature wet, cold springs. The arrival of rainy weather in June and August more closely aligned with the climatic norm and meant that the army could fully implement the waterline to protect the core of Holland by intentionally inundating surrounding landscapes. This effectively halted the enemy advance. By 1674, under the leadership of William III, the Dutch Republic concluded treaties with England and the German bishoprics, only remaining at war with France. These strategic victories signaled the turning point of this particular conflict, but they also laid the groundwork for decades of costly, destructive war with France. The Rampjaar proved a watershed moment in Dutch political history both bemoaned and welcomed, but its consequences continued to haunt the Republic well into the eighteenth century.

The immediate impact of the Rampjaar substantially affected Dutch society. The war traumatized the Dutch population, especially those that endured years of foreign occupation. Although the worst political and military effects of the Rampjaar ended by 1674, Dutch characterizations of the era in subsequent years remained inflexibly dismal. The Utrecht regent Bernard Costerus reflected that the Rampjaar reduced many “to poverty and distress and had lapsed into a wretched state, so that during their remaining years they were not able to repair their ruined livelihoods.”Footnote 45 The Dutch considered the Rampjaar a totalizing disaster, the consequences of which touched every segment of society. Perhaps no single group suffered more than rural communities living in occupied lands. In early 1672, when French soldiers marched across the eastern Dutch borderlands, through Gelderland, Overijssel, and the Generality Lands (now North Brabant and Zeelandic Flanders), the countryside bore the brunt of the violence. Pamphlets described the pillaging of cities, and publishers distributed sensationalist prints depicting the “French Savagery” that took place in towns like Zwammerdam and Bodegraven in South Holland.Footnote 46 Local economies in these inland regions suffered during this onslaught as well as years of subsequent occupation.Footnote 47

Even the waterline, heralded as a miracle of Dutch ingenuity and savior of the Republic, proved a disaster in the countryside. Rural communities actively resisted these military inundations because they protected the urban core of Holland at the expense of rural sacrifice zones. Flooded fields meant that farmers lost harvests and fodder for their livestock, and despite this loss of income, they remained responsible for repairing broken dikes after the war.Footnote 48 Faced with this onerous burden, rural villagers and citizens of border towns like Gouda, Gorkum, and Schoonhoven refused to comply with military plans for inundation and only acquiesced after Dutch soldiers arrived to quell resistance.Footnote 49 The French added to these self-inflicted assaults by breaching dikes to slow the Dutch defenders. Dutch leaders understood the economic consequences of weaponizing water. When William III ordered the construction of a new dike to protect the fertile polder lands of Rijnland in 1672, for instance, he found the rural population unable to shoulder the immense financial burden. Loss of revenue in agricultural regions prevented timely and effective maintenance of dikes for years to come. Many of the same communities affected by military inundations would later experience dike breaches during the coastal floods of 1675 and 1702.Footnote 50 The environmental and economic consequences of the Rampjaar for rural populations proved both devastating and long lasting.

Beyond its destabilizing effects in the countryside, the invasion prompted a financial panic that resulted in one of the most dramatic stock market crashes in Dutch history. Shares in the VOC collapsed, and the value of WIC stocks became “virtually worthless” overnight. Although the market would rebound, other economic indicators like public construction, property rents, and the art market experienced slumps that would take decades to recover.Footnote 51 War forced the Dutch to recall warships protecting overseas commerce to defend domestic ports. As a result, fishing and key sectors of foreign trade ground to a halt.Footnote 52 These economic disasters compounded the shock of the military defeats and political upheaval.

On a cultural level, the most telling indication of the unsettled mentality of Dutch society was the explosion of pamphlet literature. The Dutch Republic was likely the most literate society in Europe, and its printing industry fostered diverse opportunities to read and disseminate information through newspapers, books, sermons, and state resolutions. Pamphlets were among the most popular media for news and polemic. They were relatively cheap, usually vernacular, and broadly accessible. Pamphlets were thus popular tools to broadcast commentary about current events, including disasters. Dutch printers published over 1,000 pamphlets in 1672.Footnote 53

It is difficult to generalize about the authorship of pamphlets, but they certainly encompassed a wide spectrum of Dutch society and reflected its most pressing concerns and deepest divisions.Footnote 54 The documents from 1672 showcased the political conflicts that led to the revolt and coup, as well as moral, religious, and cultural tensions, such as the contested role of the Reformed Church in state governance and Dutch society’s perceived depravity. A common complaint about Dutch culture was its decay from pious modesty to extravagance and greed. “In truth,” one anonymous pamphleteer argued, “this our century has, through prosperity and good fortune, degenerated very far from the old simple manners and sobriety.”Footnote 55 The Rampjaar was evidence of God’s displeasure with this moral decline. Pamphlet literature spanned the gamut between sensationalist journalism intended to convey the horror of invasion to its readers, to social and political critique, to inventories of moral decay.

The spectacular growth and prosperity of the Dutch Golden Age had dazzled European onlookers during the seventeenth century, and Dutch citizens were justifiably optimistic about its future. To all onlookers, its near collapse in 1672 was shocking. One of the best-known foreign witnesses of the Dutch Golden Age, the English ambassador William Temple, saw 1672 as a break in Dutch history. “It must be avowed, That as This State, in the Course and Progress of its Greatness for so many Years past, has shined like a Comet; so in the Revolutions of this last Summer, It seem’d to fall like a Meteor, and has equally amazed the World by the one and the other.”Footnote 56 Combined with the cost of the war and trauma of occupation, the Rampjaar profoundly transformed Dutch politics, society, and culture, testing Dutch confidence and resilience.

1.3 The Uncertain Aftermath and Diverging Decline Narratives

The ordeals of the Rampjaar notwithstanding, long-term decline was far from a foregone conclusion in 1672. To most contemporaries, it was impossible to ignore the fact that the Dutch Republic remained the wealthiest state in Europe and retained much of its previous prestige. The state had weathered numerous trials in the past, some of which seemed eerily similar in character to the Rampjaar. The disaster year of 1570, for instance, featured the combined impacts of military invasion during the Dutch Revolt from Spain and the All Saints’ Day Flood (Allerheiligenvloed), which inundated large portions of the western Netherlands. That the Dutch Republic emerged victorious and stronger than ever following these collective calamities seemed evidence that a similar recovery was likely in 1673. Dutch statesmen in the 1670s certainly understood the gravity of their predicament. They perceived themselves beholden to an unwieldy public debt and the revenue of an overwhelmed tax base. Despite this, at the end of the seventeenth century, few thought these conditions would translate to long-lasting decline.Footnote 57

The Rampjaar, however, was merely the first in a long series of mercantile and military conflicts with an expansionary France that lasted until 1713. This period, which some historians refer to as the “Forty Years’ War,” included the Franco-Dutch War (1672–78), the Nine Years’ War (1688–97), and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–13). It also featured numerous trade wars that periodically heightened political tensions.Footnote 58 These conflicts directly affected foreign and domestic commerce, and wartime expenses required loans that saddled provinces with enormous debt.Footnote 59 Reflecting on the consequences of this period of Franco-Dutch conflict, the Dutch-born agent of France Adrianus Engelhard Helvetius reported to the French state in 1705 that “the commerce of the United Provinces in Europe has never been in a worse condition than today,” which he attributed primarily to the financial burden of prolonged warfare.Footnote 60 His report revealed more than the schadenfreude expected of a geopolitical rival. It was a critique grounded in a reality whose significance slowly gained acceptance in the Republic itself.

Foreign observers were also among the first to examine the close connection many saw between the Republic’s economic and environmental challenges. The English engineer Andrew Yarranton noted the relationship between taxation, decline, and the combined weight of military and environmental assaults. As early as 1677, he argued that “all people that know any thing of Holland, know that the people there pay great Taxes, and eat dearly, maintain many Souldiers [sic] both by Sea and Land and in the Maritime Provinces have neither good Water nor good Air … and are many times subject to be destroyed by the devouring waves of the Sea’s overflowing their banks.”Footnote 61 Holland’s economic and environmental vulnerabilities were mutually reinforcing. Unlike Dutch observers of this relationship like De Hooghe, Yarranton was far less willing to apply an optimistic lens to their implications.

Anxieties about decline gained increasing purchase in the Republic during the first decades of the eighteenth century. Rather than financial or environmental concerns, however, they pointed to moral and cultural degeneracy. Early eighteenth-century moralists argued that the Dutch Republic had lost sight of the core values of its prior Golden Age. Honesty, industriousness, thrift, and, above all, piety had been the bedrock upon which seventeenth-century success was built, and Dutch critics bemoaned its deterioration. Reformed clergymen published widely on these subjects, particularly those associated with Dutch Pietism. This movement advocated purification of personal and civic morality and saw decline as manifestation of divine judgment. Moralistic interpretations of decline were not restricted to Pietist ministers, however, nor even the clergy. Less puritanical interpretations appeared in poetry, the visual arts, state documentation, farmers’ journals, and early-modern journalism. Despite their wide-ranging backgrounds and interests, these authors shared a dual conviction that at once asserted moral and cultural loss and advocated improvement.

No writer was as influential a critic as Justus van Effen (1684–1735), the early Enlightenment publisher of the literary magazine De Hollandsche Spectator. Van Effen used his platform to feed declensionist anxiety. He and many later spectatorial writers championed ideals that were inherently backward looking – hearkening to the republican virtue of the Golden Age. They were deeply critical of a decadent eighteenth century, which, in their view, appeared increasingly polluted by French manners and fashion. On the surface, little of this critique appeared new. Moralists had long warned that sin threatened Dutch prosperity, even during the seventeenth century.Footnote 62 More novel were the connections moralists found between sin and broader anxieties about economic, political, cultural, and environmental decline.Footnote 63 These critiques grew louder and more common over the course of the early eighteenth century. By the second half of the eighteenth century, decline had assumed a near universal character.

Cultural and moral anxieties about decline during the first half of the eighteenth century also informed Dutch responses to natural disaster. In the context of the early Dutch Enlightenment, these responses increasingly emphasized novelty, innovation, and perfectibility. Natural scientists, philosophers, merchants, and state officials employed these ideas to temper fears of decline, promote greater confidence in their ability to control nature, and check longstanding anxieties about reoccurring disasters like plagues, wars, and famines. According to Peter Gay, this optimism starkly contrasted with a general fear of stagnation that reigned in Europe before the late seventeenth century. Gay famously termed this transition the “recovery of nerve.”Footnote 64 Early Enlightenment thinkers, state officials, and hydraulic experts in the Netherlands were active purveyors of these optimistic assessments. Disasters showcased how the rhetoric of innovation and improvement gradually increased over the course of the eighteenth century.Footnote 65

Natural disasters tested the Dutch mastery of nature and presented opportunities to develop new strategies to control and mitigate their effects. In contrast to bleak historical assessments of scientific stagnation, the international reputation of Dutch scientists and engineers actually increased in stature during the eighteenth century.Footnote 66 Luminaries like Willem Jacob 's Gravesande and Herman Boerhaave popularized Newtonian science on the continent and became the great teachers of Europe, while Nicholas Cruquius and Cornelis Velsen enjoyed international renown for their work in hydraulics and hydroengineering. Historians are no longer comfortable assigning declensionist labels to Dutch science in this era. In the words of one historian, “[W]hile in one field we can speak of decline, perhaps we can see progress in another, and what is decline from one perspective can be quite the opposite from another.”Footnote 67 The significance of these Enlightenment-era figures reflected the growing confidence about the Dutch ability to understand and manipulate bodies and environments and respond to natural disasters.

Environmental challenges shaped the emerging perceptions of decline. On the one hand, natural disasters seemed to confirm the most pessimistic assessments of the Dutch Republic’s changing fortunes. The repeated catastrophes of the early eighteenth century proved deadly and expensive, and each new calamitous event reinforced anxieties about the Netherland’s flagging economy. In the wake of these disasters, community response fractured in ways that seemed to confirm the breakdown of Dutch society. Catastrophes laid bare a public moral degeneration that emphasized the Dutch Republic’s diminishing providential favor. To make matters worse, the environmental liabilities already apparent in the mid-seventeenth century appeared to be worsening. The early eighteenth century seemed to present greater and deadlier disasters than ever before, or hazards of such uniqueness and novelty that they exposed the limits of Dutch political and technological capacity to respond.

On the other hand, disasters presented unequalled opportunities for adaptation and improvement. As trials of faith and reason, disasters encouraged moral self-examination and reconsideration of the distinction between their divine and “natural” origins. Natural disasters destroyed infrastructure, killed thousands, and incited confusion and violence, but they also catalyzed social solidarity, the development of new water management technologies, medical treatments to combat disease, as well as empirical and scientific examinations of the Dutch environment. Disasters revealed that decline was real, but they also showed the contours and contradictions of its development. In contrast to an eighteenth century characterized by economic torpor or what some historians have described as “a stagnation of spirit, a sapping of creative power, an end of greatness and a slide into social artificiality,” Dutch response to catastrophe paints a more resilient picture.Footnote 68 These varied responses to disaster explain the broad trajectory of decline amidst profound changes in Dutch society and its relationship with its environment.

These welcome revisions to a uniformly dreary view of Dutch society privilege scientific and technological adaptation, yet these must be balanced against resistance to change and the continuing (in some cases increasing) exposure to adversity. New plans to regulate rivers and control floods did little to lessen the very real desperation of communities rebuilding in the wake of inundations, nor did they necessarily temper anxieties about decline. Physicians, enlightened citizen-scientists, and ministers experimented with novel tools like inoculation to combat cattle plague in the 1750s, yet most state responses remained wedded to centuries-old disease management strategies. This does not diminish the value or significance of either approach. Dutch communities coped with adversity in remarkable and creative ways. Both change and continuity characterize the early eighteenth-century experience – the first privileging optimism and innovation, the other memory and tradition. Both anxiously reached back to the golden achievements of the past.