Supervision Registers are local registers, maintained by providers of mental health care in England, of patients with severe mental illness identified as being at risk (NHS Executive, 1994). Introduced in 1994, they formed part of the policy response to concern about perceived high profile failures of psychiatric care (Reference HollowayHolloway, 1994). The Supervision Registers were intended to identify all patients under the care of specialist psychiatric services “who are, or are liable to be, at risk of committing serious violence or suicide, or of serious self-neglect”. The Supervision Register policy was intended to ensure that such patients are prioritised to receive care under the Care Programme Approach (CPA), that risk information is appropriately communicated, and follow-up is maintained (Department of Health, 1995).

We aimed to : (a) establish the characteristics of individuals included on Supervision Registers; (b) compare these with patients requiring a high level of care but not regarded as at high risk; and (c) assess the views of responsible medical officers (RMOs) and keyworkers about the impact of inclusion on the Register.

METHOD

A national postal and telephone survey of all 180 mental health provider trusts in England (reported in Reference Bindman, Beck and GloverBindman et al, 1999) identified the number of patients on the Register in each trust, and also the number of ‘tiers’ used to prioritise patients within the CPA. These tiers refer to levels of intensity of psychiatric treatment and care. Sixteen trusts were randomly sampled, and approached for ethical approval and for local agreement to the study. Ethical approval was received in all cases, but at two trusts practical difficulties or failure to obtain local agreement precluded data collection. At eight of the 14 trusts visited, there were fewer than 15 patients on the local Supervision Register, and all were included. At each of the remaining six trusts, 15 patients were randomly sampled. At each trust, all patients on the top (most intensive) tier of the CPA, as locally defined, were identified, and for each Register case, a patient on the top tier CPA, matched for RMO (but for no other characteristic), was randomly sampled for comparison. The selection of the comparison group presented the difficulty that both the Supervision Register and the upper tier of the CPA were variably defined in the sampled trusts. However, the comparison group represents the most tightly defined available group of patients with severe mental illness, from which the Supervision Register group were selected by the decision of the RMO to identify them as ‘at risk’.

Case notes of all cases and comparison patients were examined by a researcher (A.B. or J.B.), and demographic and service use data were recorded. Previous incidents of violence and self-harm recorded in case notes (lifetime most severe, and most severe in the last six months) were extracted and recorded on a form designed for the purpose. Notes were read in detail, and the researcher could not be blinded to the patient's Supervision Register status. Incidents were rated for severity on a scale of 0-4 using the anchor points on the ‘overactive, aggressive, disrupted or agitated behaviour’ and ‘non-accidental self-injury’ scales included in the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS; Reference Wing, Beevor and CurtisWing et al, 1998). Each form was rated by two researchers (A.B. and J.B.), and a consensus rating made in cases of initial disagreement, which was by no more than a single point in any case. Incidents of life threatening violence (either described as such in case notes, or assaults involving stabbing or strangulation), were rated in addition. References in case notes to self-neglect were also recorded and rated as : neglect resulting in threat to life, and neglect resulting in failure to obtain adequate nourishment. The RMO of each Supervision Register case was asked to complete a questionnaire concerning the reasons for placing the patient on the Supervision Register, and the RMO's view of the effect of inclusion on the Supervision Register on the patient's care. The keyworkers of all Register cases and all CPA comparison patients were interviewed to provide current ratings (the month prior to rating, or the most recent contact if longer than a month) using the HoNOS, the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN; Reference Phelan, Slade and ThornicroftPhelan et al, 1995), and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) symptom and disability scales (Reference Endicott, Spitzer and FleissEndicott et al, 1976). They were also asked at interview to complete a questionnaire concerning their views of the effect of inclusion on the Supervision Register on the management of each case.

Data analysis

Data were entered into a database and analysed using STATA for Windows (STATA Corporation, 1997). Descriptive statistics were used for the survey results, and Supervision Register cases and CPA comparison patients were compared using X 2 and t-tests for categorical and continuous variables as appropriate, and a non-parametric test for trend (‘nptrend’) for the ordered categorical variables resulting from the HoNOS ratings of violence and self-harm.

RESULTS

Numbers registered on Supervision Register and reasons for inclusion

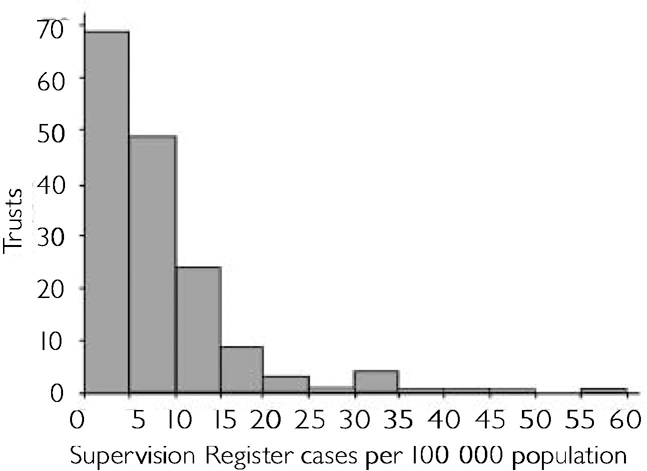

Postal survey responses were received from 163 trusts (91%) and following telephone contact with the remainder the number on the Supervision Register was established in 180 trusts (100%). By mid-1997, three years from the introduction of the policy, patients were included on the Supervision Register in 175 trusts (97%), and in one trust with no patients currently registered, the Register had been used previously. Numbers registered per trust varied from 0 to 194, with a mean of 23 and a median of 14.5; the total registered nationally was 4136. The total population served was known in 164 trusts (91%), and at these the mean number of patients registered was 8.6 per 100 000 total population, the median 6.4, and the range 0-55.4 (Fig. 1).

Fig. I Number of patients on Supervision Registers per 100 000 total population served in England (mean 8.6, s.d. = 9.12, n = 164).

As shown elsewhere (Reference Bindman, Beck and GloverBindman et al, 1999), variations in local need do not explain the variation in the numbers, which instead reflect the application of inconsistent criteria for inclusion.

Characteristics of patients registered

Of 140 Supervision Register cases sampled as described above, data were obtained on 133 (95%), and of the 133 comparison patients, matched for RMO, data was obtained on 126 (95%). The demographic and service use characteristics of patients and comparison patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients on the Supervision Register and Care Programme Approach

| Characteristic | Supervision Register cases (n = 133) | Care Programme Approach comparison patients (n = 126) | Significance of difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 72% male | 55% male | X 2 = 10.1, P <0.01 |

| Mean age | 39.2 | 41.9 | t = 1.5, P = 0.13 |

| Single, separated, divorced | 81.1% | 78.0% | X 2 = 0.36, P = 0.55 |

| Living alone | 43.5% | 41.8% | X 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 |

| Admissions, lifetime | 7.5 | 5.7 | t = 2.8, P <0.01 |

| Mean years since first contact | 14.1 | 13.2 | t = 0.7, P = 0.51 |

| Ever in Regional Secure Unit | 17% | 3% | X 2 = 12.7, P <0.001 |

| Ever in prison | 24% | 8% | X 2 = 11.7, P <0.001 |

| Ever in Special Hospital | 5% | 1% | X 2 = 3.7, P = 0.06 |

Keyworkers' ratings of Supervision Register cases and CPA comparison patients on the HoNOS, GAF and CAN scales are shown in Table 2. The GAF scores show that as a group Supervision Register cases have high levels of symptoms and disability, significantly greater than comparison patients. The total HoNOS score confirms this finding. Examining HoNOS item scores, the Supervision Register cases are rated as having higher levels of overactive/aggressive behaviour, hallucinations and delusions, and physical illness or disability, when compared with comparison patients (P <0.01, X 2 test for trend). The overall number of needs, as measured by the CAN, is significantly higher among Supervision Register cases, as is the number of met needs. This would support the view that patients on Registers are correctly identified as being those in greatest need, and that services are responding appropriately to their needs. However, the absolute difference in total and in met needs between the Supervision Register and comparison groups is small, and the Supervision Register cases also have slightly higher unmet needs, though this difference is significant only at the 10% level.

Table 2 Keyworkers' ratings of Supervision Register cases and Care Programme Approach comparison patients on the HoNOS, GAF and CAN scales

| Rating | Supervision Register cases | Care Programme Approach comparison patients | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HoNOS total score | 14.6 (n=118) | 12.0 (n=110) | t=2.4, P=0.02 |

| GAF disability | 50.7 (n=117) | 58.4 (n=112) | t=3.2, P=0.002 |

| GAF symptom | 47.7 (n=117) | 57.7 (n=112) | t=3.8, P < 0.001 |

| CAN total needs | 8.1 (n=121) | 7.1 (n=115) | t=2.7, P=0.01 |

| CAN met needs | 5.2 (n=121) | 4.5 (n=115) | t=2.0, P=0.05 |

| CAN unmet needs | 3.1 (n=121) | 2.6 (n=115) | t=1.6, P=0.10 |

Incidents of aggression, self-harm, and self-neglect

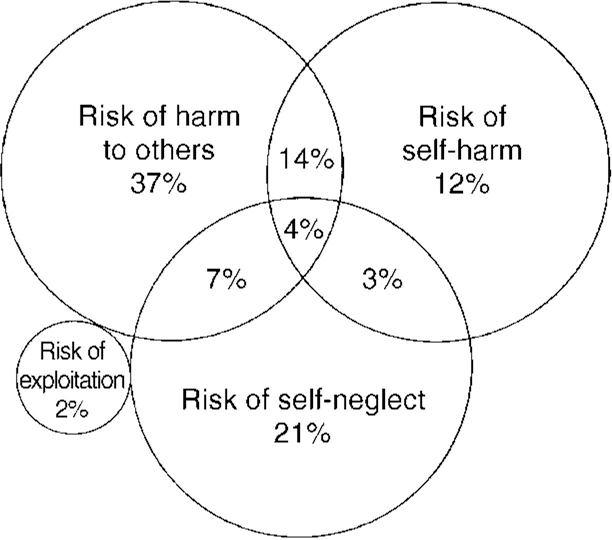

Structured assessments of risk were largely absent from case notes of Register cases, and in only 50 cases (37%) was any justification of inclusion on the Supervision Register (other than a simple statement of entry and category of risk) recorded. Fig. 2 shows that the risk of violence, alone or in combination with other categories, was the most common reason for placing patients on the Supervision Register, and risk of selfharm was the least common. The relatively high use of the self-neglect category, despite its lower profile as an area for concern by psychiatric services, suggests that it may be regarded by psychiatrists as more predictable, or easier to prevent, than violence or suicide.

Fig. 2 Use of categories for placing patients on the Supervision Register (n = 131; two cases for which no category was recorded in case notes or by the trust are excluded).

History of aggression in patients registered as a risk to others

Of the 133 Supervision Register cases, 81 (61%) were registered as being at risk of harming others (32 of whom were also in other risk categories). In 14 of these cases (17%) there was no history of any aggression recorded in case notes (equivalent to HoNOS score 0), and in a further 14 (17%) only verbal aggression was recorded (HoNOS score 2). Eight patients (10%) had behaved in a threatening way (HoNOS score 3), and 45 (56%) had committed an actual physical assault equivalent to a HoNOS rating of 4. Few of the recorded incidents were recent, 51 cases (63%) having no recorded aggression within the last 6 months, and only nine (11%) having committed an actual assault (HoNOS score 4).

The Supervision Register cases had significantly higher levels of recorded aggression (z=-7.6, P < 0.001) than the CPA comparisons (of whom 15 cases, 12%, had committed an actual assault, equivalent to a HoNOS rating of 4). In addition, of the Register cases who were recorded as committing assaults, nine had committed life-threatening assaults, of whom one had committed homicide many years previously. One of the comparison group had committed a life-threatening assault and one had committed homicide many years previously and was subject to restriction under Section 49 of the Mental Health Act 1983.

Patients categorised as at risk of self-harm

Forty-three patients were registered in the category of risk of self-harm (of whom 27 were also in other categories). Rating incidents recorded in case notes using the equivalent of the HoNOS self-harm rating, 10 cases (23%) had no record of any lifetime suicidal thoughts or behaviour, and a further five (11%) only ‘minor risk’ (equivalent to a HoNOS rating of 1 or 2). Seven cases (16%) were recorded as having been regarded as at ‘moderate risk’ (HoNOS score of 3), and 21 (49%) had incidents of actual self-harm (HoNOS score 4) recorded in case notes. Few incidents were recent, only four cases (9%) having made a serious attempt at self-harm (HoNOS score of 4) in the previous six months.

Though Supervision Register cases had significantly higher levels of recorded self harm (z=-4.7, P < 0.001), 23 (18%) of the comparison group had made recorded suicide attempts rated as a HoNOS score of 4. As for aggression, though the Register cases as a group are at higher risk than the comparison group, many patients with no recorded history of actual self-harm are included in this supposedly very high risk group, and risk assessment in this area is again inconsistent.

Patients categorised as at risk of self-neglect

There is no standard method of assessing self-neglect, but we were able to identify from case notes that of 45 patients registered as at risk of self-neglect (18 of whom were in other categories as well), 16 (36%) had been noted as at some time suffering weight loss as a result of failing to obtain adequate food, compared with 20 (16%) in the comparison group, and that seven (16%) cases on the Register had been recorded as neglecting themselves to a life-threatening extent compared with 12 (10%) in the comparison group (z=-3.8, P < 0.001).

Keyworker and RMO opinions of the effectiveness of the Supervision Register

The keyworkers of 111 (83.5%) of the cases on the Supervision Register responded to questions about their views of the effectiveness of the Register in ensuring prioritisation, communication about risk, and preventing loss to follow-up. After repeated mailings and telephone contacts, a total of 37 RMOs answered similar questions in relation to 92 (69%) of the Register cases. All responses were rated as positive or negative. The keyworkers believed that in 81 cases (73%) the patients had not been prioritised to receive more services than they otherwise would have done, in 77 cases (69%) the risk of loss to follow-up had not been reduced, and in 70 cases (63%) information sharing had not improved as a consequence of inclusion on the Supervision Register. The RMOs believed that in 68 cases (74%) placing the patient on the Supervision Register had not had any benefits. In the 24 cases (26%) where benefits were believed to have resulted, these included improved prioritisation, follow-up and communication, but also consequences such as influencing discharge from restriction or reassuring patients' relatives, which may not have been associated with direct benefits for the patient.

DISCUSSION

Impact of the policy

The policy has been almost universally implemented according to the guidelines issued in 1994, and almost all trusts have developed local Supervision Registers, though the numbers registered by different trusts are highly variable. The patients in our sample of Supervision Register cases are a group with high levels of need, disability and current symptoms. However, though as a group the Register cases have higher levels of recorded risk behaviours than patients selected for the upper tier of the CPA, many individuals with no recorded history of aggression, self-harm or self-neglect have been registered as at risk.

Criteria of risk

The study is limited by the lack of any ‘gold standard’ measures of individual risk, and in choosing to measure recorded incidents of risk behaviours, we have used the only available proxy for actual risk.

The difficulty of measuring individual risk underlay the concern expressed at the introduction of the Supervision Registers, that the criteria for entry to the register were unclear (Reference CaldicottCaldicott, 1994; Reference HarrisonHarrison, 1994). Prior to the introduction of the Supervision Registers, some estimates of the numbers of patients likely to be registered used broad criteria of risk and large registers were predicted, from between 40 and 160 patients per 100 000 total population (Reference Pugh, Gardner and AllenPugh et al, 1994; Reference LaugharneLaugharne, 1994) to 300 people per 100 000 total population (Reference CaldicottCaldicott, 1994). Though no formal target was suggested by the Department of Health, they suggested instead that narrow criteria should be adopted (Reference Glover, McCulloch and JenkinsGlover et al, 1994), and that these might result in the placing on the Supervision Register of 15 cases per 100 000 (Reference HollowayHolloway, 1994). In practice, though even the largest registers have not approached the highest predictions, and the average is well below the lowest, there is evidence that both wide and narrow risk criteria are in use in different trusts. In the absence of sensitive and specific tests of risk, the adoption of either broad or narrow criteria is likely to be ineffective. Using broad criteria many lowrisk individuals will be included, wasting resources or causing the measure to be regarded as a mere paper exercise, and using narrow criteria a few ‘token’ cases with extreme histories will be selected and the impact on the overall level of risk, to patients or to the community, will be small. However, such variable application of the policy is inevitable, given the lack of operationalised definitions of risks, and of sensitive, specific instruments for assessing them (Reference Monahan, Monahan and SteadmanMonahan, 1994; Reference Gunnell and FrankelGunnell & Frankel, 1994), particularly for non-forensic populations.

Views of effectiveness of the policy

In practice it appears that there is considerable doubt about the effectiveness of the policy in improving care for individual patients, a majority of keyworkers and RMOs regarding the policy as not having had the positive impact intended.

Implications

The CPA policy has recently been reviewed, and trusts will be permitted to discontinue Supervision Registers from April 2001 if a simplified two-tier CPA, of which “risk assessment is an ongoing and essential part” is functioning effectively (Department of Health, 1999). This may make it possible for individuals to receive the benefits of prioritisation without stigmatisation. However, while removing Supervision Registers and integrating risk assessment further into the CPA may make the lack of consensus about risk assessment suggested by this study less apparent, it will remain a problem. The Mental Health Act 1983 is currently under review, and new measures aimed at high-risk individuals in community-based psychiatric populations are being considered (Reference DobsonDobson, 1998). It seems probable that most clinicians will identify only a small number of individuals as at risk in response to policies emphasising risk assessment (Reference Bindman, Beck and GloverBindman et al, 1999; Reference Pinfold, Bindman and FriedliPinfold et al, 1999), and given the low specificity of risk prediction, the overall impact on risk in the community is likely to be limited (Reference Shaw, Appleby and AmosShaw et al, 1999). The possibility remains, however, that in some services large numbers of low-risk individuals may be targeted, with implications for civil liberties and for equity of service provision.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS AND LIMITATIONS

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ The Supervision Register is used inconsistently between trusts, and this is likely to result from lack of definition of the entry criteria.

-

▪ Reasons for regarding patients as at risk should be recorded in case notes; in the absence of any actual history of risk behaviour this needs justification.

-

▪ While there is so little consensus about the identification of high-risk groups in general psychiatric practice, future legislation aimed at high-risk groups will be inconsistently applied.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ There are no established measures with which to assess risk from case notes. In the absence of a measure of ‘true’ risk, we have instead used recorded history of violence or self-harm as the best available proxy.

-

▪ The recording of risk behaviours in case notes may be biased by the patient's Supervision Register status, as may the extraction and rating of these incidents by the researcher, who could not be blinded to the Supervision Register status of the patient.

-

▪ Keyworkers' and responsible medical officers' opinions about the impact of inclusion on the Supervision Register could be biased, either negatively by general hostility to the policy, or positively to justify their own role in including the patient.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.