INTRODUCTION

Emergency medicine is fraught with uncertainty, and excessive testing is common.Reference Kanzaria, Hoffman and Probst1–Reference van Walraven and Naylor4 Physicians cite medicolegal concerns, patient expectations, and desire for diagnostic certainty as justification for over-investigation. Poor test use creates diagnoses that do not exist and misses those that do,Reference van Walraven and Naylor4–Reference Rang6 causing inappropriate treatment and patient anxiety.Reference Rang6, Reference McDonald, Daly and Jelinek7 Test ordering has not been shown to reassure patients, even when we would expect it to.Reference McDonald, Daly and Jelinek7–Reference van Ravesteijn, van Dijk and Darmon10

To be “useful,” a diagnostic test should be accurate, tell us something we don't already know, and change management in a way that improves patient outcome.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5, Reference Siontis, Siontis, Contopoulos-Ioannidis and Ioannidis11 Despite the apparent dependency on tests in medicine, relatively few tests meet this bar, especially in the emergency setting.Reference van de Wijngaart, Scherrenburg and van den Broek12 The wrong test in the wrong circumstance is likely to provide the wrong answer or, at best, no benefit. Appropriate test selection and interpretation require operators to have specific cognitive skills, a basic knowledge of diagnostic testing principles, and an awareness of their affective bias toward testing.

In today's access-blocked emergency departments (EDs), many tests are ordered by nurses or trainees to expedite patient care.Reference Chu, Wagholikar and Greenslade3, Reference Tainter, Gentges, Thomas and Burns13 These users often have limited experience interpreting test results, scant training in testing theory, and an exaggerated sense of test utility.Reference Tainter, Gentges, Thomas and Burns13 Our objective is to describe a minimum knowledge set for every clinician who orders tests in the ED, and propose a five-step cognitive tool to apply before ordering tests (Table 1).

Table 1. The five steps to rational test ordering in the ED

Step 1: Before ordering a test, decide what diagnosis you are investigating

The clinical evaluation is the foundation of diagnosis. Identifying the most likely condition(s) is based on history and physical examination. Tests rarely “tell us” the diagnosis; rather, they modify the pretest likelihood of the disease under consideration. A common mistake is to order a broad range of “routine” tests and see “what shows up.” Unfortunately, tests ordered without good justification are often misleading – falsely negative or falsely positive. A normal white count doesn't rule out appendicitis, and an elevated D-dimer doesn't rule-in pulmonary embolism (PE); it may be positive in pneumonia, trauma, cancer, pregnancy, and many other conditions. Determining the likely diagnoses before ordering a test will help interpret unexpected findings. Better, it will reduce the ordering of tests that can only confuse matters.

Step 2: Determine the pretest probability of the condition in question

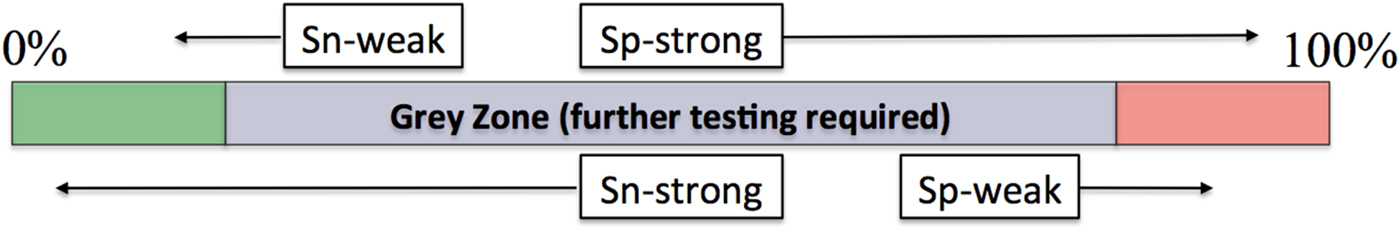

After deciding what condition you are most concerned about, use clinical judgment to estimate its pretest likelihood on a conceptual decision line from 0–100% (Figure 1). If clinical findings suggest that pretest likelihood is low, falling to the left of the testing threshold, the patient requires no further testing for that condition. The testing threshold, or negative decision threshold, also represents the level of clinical likelihood at which the risk of a false-positive result exceeds the likely diagnostic value of doing the test.

If clinical findings strongly suggest that the patient has the condition of interest and their pretest likelihood falls to the right of the treatment threshold, additional laboratory testing is not needed, and treatment or referral is appropriate. Bayesian principles indicate that, in patients with low pretest likelihood, positive tests are usually false positives, whereas, in patients with high pretest likelihood, negative tests are usually false negatives.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5 Consequently, ordering tests after a decision threshold has been achieved can lead to confusion or error.

The testing threshold varies according to the potential hazard of the disease in question.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5, Reference McGee14 For a possible cervical spine fracture, set the testing threshold very low (e.g., 1% likelihood) because diagnostic certainty is necessary and discharging someone with a 5% chance of spine fracture is a recipe for disaster. For a possible radial head fracture, set the testing threshold higher, perhaps at 30%. Some diagnostic uncertainty is acceptable with this injury because the likelihood of an adverse outcome is remote. You would never order a computed tomography (CT) to resolve uncertainty for a possible radial head fracture, but you would for a possible spine fracture.

The treatment threshold varies according to the potential risks of treatment.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5, Reference McGee14 If the treatment is benign (e.g., a dexamethasone dose for possible croup), less diagnostic certainty is required and a treatment threshold of 65% may be acceptable. If the treatment is potentially harmful (e.g., anticoagulation for PE), high diagnostic certainty is required and a high treatment threshold, perhaps 95%, is appropriate.

Step 3: Decide whether to rule the condition in or out? (SPIN or SNOUT)

When pretest likelihood assessment places the patient in a diagnostic grey zone, further testing is required. To “rule-out” a potentially dangerous diagnosis, choose a “sensitive” test (SNOUT), with the hope that a negative result will carry you across a testing threshold and eliminate the need for further testing. A urinalysis in a weak elderly patient is sensitive, yet not specific. A negative result rules out urosepsis, whereas a positive result, which may reflect coincidental asymptomatic bacteriuria, would not rule-in a urinary tract infection as the cause of weakness. Much of what we do in emergency medicine involves ruling out serious conditions and therefore we rely heavily on sensitive tests. Consultant services, preparing to commit to therapies with the potential for serious adverse effects, often rely on specific tests.

To confirm or “rule-in” a diagnosis, select a specific test (SPIN) with the hope that a positive result will carry you across a treatment threshold, providing the confidence to proceed with intervention. A FAST exam in a hypotensive trauma patient is specific, not sensitive. A positive result will prompt surgical exploration, but a negative result doesn't rule-out anything, leaving you in a diagnostic grey zone and necessitating further testing.

The pretest clinical likelihood also drives test selection. If a pretest likelihood places you far from a decision threshold, a strong test that substantially changes a posttest likelihood is necessary (Figure 2). If a pretest likelihood places you close to a decision threshold, a much weaker test will suffice. The D-dimer is sensitive but relatively weak. It is adequate to rule out PE in a person near the testing threshold with low clinical risk. Being nonspecific, the D-dimer cannot rule-in disease. A CT is both sensitive and specific, a strong test that can rule-in or rule-out disease when weaker tests can't do the job. Weak tests tend to be cheap and non-invasive, whereas strong tests are typically expensive or invasive. The strength of a diagnostic test is expressed by its likelihood ratio (LR).

Figure 2. What type of diagnostic test is required?

LRsReference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5, Reference McGee14 are the best indicator of test strength and are used as multipliers of pretest likelihood. Mathematically, a positive LR (LR+) is the ratio of true positive over false positive results, whereas a negative LR (LR-) is the ratio of false negative over true negative results.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5 Simply put, as LR+ increases, tests become stronger positive predictors (high specificity), and as LR- diminishes, they become stronger negative predictors (high sensitivity). Tests with LR+ of 1.0–3.0 are weak, whereas those with LR+ > 10 are powerful and often diagnostic. Tests with LR- of 0.3–1.0 are weak, whereas those with LR- of <0.1 are powerful and often diagnostic. The Fagan nomogramReference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5 (available on the Internet),15 used to determine the posttest likelihood given pretest likelihood and likelihood ratio, can help determine whether a test will change the pretest probability enough to rule in or rule out a diagnosis.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5

Step 4: Decide what you will do if the test result is positive or negative

Confirmation bias is the tendency to act on results that support our pre-existing belief and to disregard results that don't.Reference Pines16 It is difficult to prevent confirmation bias from interfering with our evaluation of new information. It is therefore helpful to determine before ordering a test how to respond to its result. If a test result won't change management, it may be of little value, and if an unexpected result will be ignored, avoid ordering the test. When the clinical pretest likelihood is very high or very low, test results that disagree with the clinical impression are likely to be incorrect and may lead to inappropriate management decisions. A white blood cell count in a patient with suspected infection often falls into this category. When test results are equivocal (e.g., nonspecific T-wave changes), they should be treated as unhelpful in altering pretest probability, and alternative tests should be considered.

Step 5: Ask whether ordering this test could hurt your patient

The lower the risk of the condition, and the higher the risk of testing and treatment, the lower the potential benefit of testing. If the risk of the condition being considered is less than the risk of testing, doing nothing or proceeding based on clinical judgment is the best option. For example, if the risk of a child's minor head injury is less than the risk of radiating a developing brain, we should not expose the patient to a CT. A familiar example is the use of a lumbar spine X-ray. For a patient with back pain and no “red flags,” the test exposes the patient to a poorer outcome than if no X-ray was done.Reference Kendrick, Fielding and Bentley17

INTRODUCTION

Emergency medicine is fraught with uncertainty, and excessive testing is common.Reference Kanzaria, Hoffman and Probst1–Reference van Walraven and Naylor4 Physicians cite medicolegal concerns, patient expectations, and desire for diagnostic certainty as justification for over-investigation. Poor test use creates diagnoses that do not exist and misses those that do,Reference van Walraven and Naylor4–Reference Rang6 causing inappropriate treatment and patient anxiety.Reference Rang6, Reference McDonald, Daly and Jelinek7 Test ordering has not been shown to reassure patients, even when we would expect it to.Reference McDonald, Daly and Jelinek7–Reference van Ravesteijn, van Dijk and Darmon10

To be “useful,” a diagnostic test should be accurate, tell us something we don't already know, and change management in a way that improves patient outcome.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5, Reference Siontis, Siontis, Contopoulos-Ioannidis and Ioannidis11 Despite the apparent dependency on tests in medicine, relatively few tests meet this bar, especially in the emergency setting.Reference van de Wijngaart, Scherrenburg and van den Broek12 The wrong test in the wrong circumstance is likely to provide the wrong answer or, at best, no benefit. Appropriate test selection and interpretation require operators to have specific cognitive skills, a basic knowledge of diagnostic testing principles, and an awareness of their affective bias toward testing.

In today's access-blocked emergency departments (EDs), many tests are ordered by nurses or trainees to expedite patient care.Reference Chu, Wagholikar and Greenslade3, Reference Tainter, Gentges, Thomas and Burns13 These users often have limited experience interpreting test results, scant training in testing theory, and an exaggerated sense of test utility.Reference Tainter, Gentges, Thomas and Burns13 Our objective is to describe a minimum knowledge set for every clinician who orders tests in the ED, and propose a five-step cognitive tool to apply before ordering tests (Table 1).

Table 1. The five steps to rational test ordering in the ED

Step 1: Before ordering a test, decide what diagnosis you are investigating

The clinical evaluation is the foundation of diagnosis. Identifying the most likely condition(s) is based on history and physical examination. Tests rarely “tell us” the diagnosis; rather, they modify the pretest likelihood of the disease under consideration. A common mistake is to order a broad range of “routine” tests and see “what shows up.” Unfortunately, tests ordered without good justification are often misleading – falsely negative or falsely positive. A normal white count doesn't rule out appendicitis, and an elevated D-dimer doesn't rule-in pulmonary embolism (PE); it may be positive in pneumonia, trauma, cancer, pregnancy, and many other conditions. Determining the likely diagnoses before ordering a test will help interpret unexpected findings. Better, it will reduce the ordering of tests that can only confuse matters.

Step 2: Determine the pretest probability of the condition in question

After deciding what condition you are most concerned about, use clinical judgment to estimate its pretest likelihood on a conceptual decision line from 0–100% (Figure 1). If clinical findings suggest that pretest likelihood is low, falling to the left of the testing threshold, the patient requires no further testing for that condition. The testing threshold, or negative decision threshold, also represents the level of clinical likelihood at which the risk of a false-positive result exceeds the likely diagnostic value of doing the test.

Figure 1. Diagnostic decision line representing a pretest probability of disease.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5

If clinical findings strongly suggest that the patient has the condition of interest and their pretest likelihood falls to the right of the treatment threshold, additional laboratory testing is not needed, and treatment or referral is appropriate. Bayesian principles indicate that, in patients with low pretest likelihood, positive tests are usually false positives, whereas, in patients with high pretest likelihood, negative tests are usually false negatives.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5 Consequently, ordering tests after a decision threshold has been achieved can lead to confusion or error.

The testing threshold varies according to the potential hazard of the disease in question.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5, Reference McGee14 For a possible cervical spine fracture, set the testing threshold very low (e.g., 1% likelihood) because diagnostic certainty is necessary and discharging someone with a 5% chance of spine fracture is a recipe for disaster. For a possible radial head fracture, set the testing threshold higher, perhaps at 30%. Some diagnostic uncertainty is acceptable with this injury because the likelihood of an adverse outcome is remote. You would never order a computed tomography (CT) to resolve uncertainty for a possible radial head fracture, but you would for a possible spine fracture.

The treatment threshold varies according to the potential risks of treatment.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5, Reference McGee14 If the treatment is benign (e.g., a dexamethasone dose for possible croup), less diagnostic certainty is required and a treatment threshold of 65% may be acceptable. If the treatment is potentially harmful (e.g., anticoagulation for PE), high diagnostic certainty is required and a high treatment threshold, perhaps 95%, is appropriate.

Step 3: Decide whether to rule the condition in or out? (SPIN or SNOUT)

When pretest likelihood assessment places the patient in a diagnostic grey zone, further testing is required. To “rule-out” a potentially dangerous diagnosis, choose a “sensitive” test (SNOUT), with the hope that a negative result will carry you across a testing threshold and eliminate the need for further testing. A urinalysis in a weak elderly patient is sensitive, yet not specific. A negative result rules out urosepsis, whereas a positive result, which may reflect coincidental asymptomatic bacteriuria, would not rule-in a urinary tract infection as the cause of weakness. Much of what we do in emergency medicine involves ruling out serious conditions and therefore we rely heavily on sensitive tests. Consultant services, preparing to commit to therapies with the potential for serious adverse effects, often rely on specific tests.

To confirm or “rule-in” a diagnosis, select a specific test (SPIN) with the hope that a positive result will carry you across a treatment threshold, providing the confidence to proceed with intervention. A FAST exam in a hypotensive trauma patient is specific, not sensitive. A positive result will prompt surgical exploration, but a negative result doesn't rule-out anything, leaving you in a diagnostic grey zone and necessitating further testing.

The pretest clinical likelihood also drives test selection. If a pretest likelihood places you far from a decision threshold, a strong test that substantially changes a posttest likelihood is necessary (Figure 2). If a pretest likelihood places you close to a decision threshold, a much weaker test will suffice. The D-dimer is sensitive but relatively weak. It is adequate to rule out PE in a person near the testing threshold with low clinical risk. Being nonspecific, the D-dimer cannot rule-in disease. A CT is both sensitive and specific, a strong test that can rule-in or rule-out disease when weaker tests can't do the job. Weak tests tend to be cheap and non-invasive, whereas strong tests are typically expensive or invasive. The strength of a diagnostic test is expressed by its likelihood ratio (LR).

Figure 2. What type of diagnostic test is required?

LRsReference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5, Reference McGee14 are the best indicator of test strength and are used as multipliers of pretest likelihood. Mathematically, a positive LR (LR+) is the ratio of true positive over false positive results, whereas a negative LR (LR-) is the ratio of false negative over true negative results.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5 Simply put, as LR+ increases, tests become stronger positive predictors (high specificity), and as LR- diminishes, they become stronger negative predictors (high sensitivity). Tests with LR+ of 1.0–3.0 are weak, whereas those with LR+ > 10 are powerful and often diagnostic. Tests with LR- of 0.3–1.0 are weak, whereas those with LR- of <0.1 are powerful and often diagnostic. The Fagan nomogramReference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5 (available on the Internet),15 used to determine the posttest likelihood given pretest likelihood and likelihood ratio, can help determine whether a test will change the pretest probability enough to rule in or rule out a diagnosis.Reference Worster, Innes and Abu-Laban5

Step 4: Decide what you will do if the test result is positive or negative

Confirmation bias is the tendency to act on results that support our pre-existing belief and to disregard results that don't.Reference Pines16 It is difficult to prevent confirmation bias from interfering with our evaluation of new information. It is therefore helpful to determine before ordering a test how to respond to its result. If a test result won't change management, it may be of little value, and if an unexpected result will be ignored, avoid ordering the test. When the clinical pretest likelihood is very high or very low, test results that disagree with the clinical impression are likely to be incorrect and may lead to inappropriate management decisions. A white blood cell count in a patient with suspected infection often falls into this category. When test results are equivocal (e.g., nonspecific T-wave changes), they should be treated as unhelpful in altering pretest probability, and alternative tests should be considered.

Step 5: Ask whether ordering this test could hurt your patient

The lower the risk of the condition, and the higher the risk of testing and treatment, the lower the potential benefit of testing. If the risk of the condition being considered is less than the risk of testing, doing nothing or proceeding based on clinical judgment is the best option. For example, if the risk of a child's minor head injury is less than the risk of radiating a developing brain, we should not expose the patient to a CT. A familiar example is the use of a lumbar spine X-ray. For a patient with back pain and no “red flags,” the test exposes the patient to a poorer outcome than if no X-ray was done.Reference Kendrick, Fielding and Bentley17

CONCLUSION

Diagnostic testing is a critical component of emergency practice; however, it often provides no benefit to patients. Tests should never be considered “routine.” Appropriate test selection and interpretation require a sense of pretest clinical likelihood and a basic understanding of testing principles. This five-step process should help caregivers decide when, if, and how to use diagnostic tests in the ED.

Competing interests

Drs. Campbell, Magee, and Rowe are all members of the Choosing Wisely Working Group for the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP). At the time of conceptualization, Dr. Rowe's research was supported by a Canada Research Chair in Evidence-based Emergency Medicine from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) through the Government of Canada (Ottawa, ON). The funders and CWC take no responsibility for the content of this manuscript.