On the rue Philippe de Girard in Montmartre the restaurant’s front door is closed, as if no longer in business. A young man loiters nearby to direct customers to an entry from the alley. Inside, drinks are ready at the zinc counter and the menu offers exemplary fare for the Occupation years. Rutabagas, leeks and Jerusalem artichokes (topinambours) are the staple vegetables. But there are rare meat dishes as well, and pâté, and real coffee, and desserts made with real sugar, and even chocolate, all long unavailable in restaurants abiding by ration restrictions. The restaurant, Le couvre-feu, offers period dishes with black-market supplements. The staff are actors costumed to play wartime roles. This is retro café theatre in 1990. The décor and menu give patrons the atmosphere and flavours of the Occupation, without its dangers, or its very real privations.Footnote 1

Black-market activity was pervasive in wartime France, and distributed a growing share of the resources essential for survival. In his last diary entry in December 1942, the Jewish journalist Jacques Biélinky wrote that anyone trying to live on the food from ration tickets alone would starve. ‘The black market takes everything, and those who live on their tickets are condemned to starve.’Footnote 2 Regional directors of the Bank of France, reporting on economic activity across France, found it impossible in 1942 to calculate the proportion of licit to illicit commerce. The borderline between the two had become too uncertain and the trend clearly favoured growth of the ‘parallel economy’ outside the law. Official estimates of the volume of black-market traffic and prices understated their real extent. ‘From the observation of daily practices that have become normal in commerce and consumption, it is clear that only a slender minority of French people get their provisions and live in conformity with the rules, respecting rations and prices, and those who do so usually lack the resources needed to break this constraint. The vast majority seek supplements outside the normal networks for distribution.’Footnote 3 That such daily practices now looked ‘normal’ to Bank directors shows the importance of the illicit traffic and the changing moral values for everyday consumption. This parallel market continued and increased after Liberation. British visitors in early 1945 remarked on the public character of the black market and the absence of state control: ‘without the black market France cannot exist’.Footnote 4

Adapting to wartime shortages required innovation at every level: to find scarce goods, to develop new consumer practices and adjust moral standards in order to secure essentials, as well as to exploit opportunities for profit from the deprivation and desperation of others. The world of consumption was transformed by the prolonged shortages and the urgent need to find essential goods. It fostered a climate of working around the rules, improvising ways of ‘getting by’ (known as le système D), with constant improvisation to evade restrictions and ameliorate shortages. Consumers sought products no longer available in official markets. Shopkeepers tried to restock goods they had sold. Producers needed raw materials, labour and markets. Intermediaries became critically important, seizing opportunities to profit from price movements that under normal circumstances would work in legal markets to encourage the production of needed goods and deliver them to customers. The economist Charles Rist described the changes as a moral and material regression, with ‘morally unscrupulous middlemen’ now in control.Footnote 5 The state, trying to control prices and distribute goods equitably, took an unprecedented role in economic direction, a role for which it was unprepared and ill equipped.

Black markets during the war can be viewed in many ways: as providing essential means for survival, as popular resistance to state tyranny invading daily life, as a system for German exploitation, and as a means for unscrupulous producers and dealers to profit from French misery. The Vichy period fascinates us because the choices made in wartime, in the hazardous circumstances of Occupied France, lay bare fundamental issues of human behaviour and moral values in times of crisis, when even incidental choices could carry fatal consequences. Individuals made day-to-day decisions based on their immediate circumstances, with limited knowledge of where their choices could lead.

Black-market activity is defined by state laws and enforcement. Price controls and rations to equalize access to limited resources add restrictions; opportunities can then multiply for economic offences and illicit profit. Motives for violating the new laws can range from mothers buying extra milk to feed their children, to factory directors trading finished goods for raw materials to keep their firm running and their workers employed, a Joseph Joinovici selling scrap metal to the Germans for enormous profit, and a Luftwaffe Colonel Veltjens coordinating black-market purchasing by the German military to buy hoarded consumer goods including toys, women’s shoes, lingerie and cosmetics.

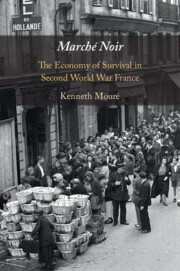

Marché Noir investigates black-market experience in France during and after the Occupation, with a focus on the logic and pervasiveness of black-market practices and their importance as a response to economic controls. The proliferation of black-market activity engages vital issues in the exercise of state power, the consequences of French collaboration with German authorities, popular resistance to state controls, consumer adaptations to survive the shortages and adversity, and change in expectations for social and economic behaviour. The shortages, controls, and criminal activity persisted after Liberation. Marché Noir provides new explanation and analysis of the exceptional character of black-market experience in France. The issues in black-market use engage fundamental questions concerning the effectiveness of state policies, the policing of markets, the economic origins of popular protest, and the difficulties that slowed France’s postwar recovery from the economy of penury.

Surviving the Economy of Penury

Everyday life in Occupied France became a struggle to survive shortages. The time and effort needed to locate and purchase essential goods, especially food, made attention to daily needs the principal concern for most civilians. Consumption practices seemed to have retreated to the nineteenth-century. Production fell. Internal borders and the scarcity of vehicles and fuel crippled transport. Industrialists lost access to the raw materials essential to their manufacturing. Farmers desperately needed tools, fertilizer, and transport for their crops. Private exchanges and barter took the place of retail purchase for scarce goods, and trade in second-hand merchandise thrived. Quality was compromised by substitutions, ersatz goods and deliberate degradations to extend scarce supplies. With shortages of vehicles and fuel, Parisians relied on bicycles and horse-drawn cabs, the streets strangely quiet. Consumers adapted to penury, localized economies, and needs-based moral compromise. Mothers ran households without husbands, anxiously seeking food for hungry children. From Nice, the worst-hit urban centre for food shortages, one housewife wrote to a friend in October 1941 that she had queued for three hours to obtain one kilo of chard for her family of five:

It’s a true famine, you can no longer find anything. There are terrible scenes of women fainting, crying, children and adults stealing, and as for me, it’s a great struggle to keep myself from doing the same. I’m haunted by the idea of stealing when I see food. Two women friends tell me that they’ve stolen bread. I hope you never experience what we have been living these last two months.Footnote 6

Her letter conveys the shock and desperation of trying to feed her family in the second autumn of the Occupation, with no way of knowing how long such conditions would last or how to adapt should they get worse.

The shortages posed immediate challenges and prompted adaptations at three inter-related levels. First, for consumers, the disappearance of goods essential to everyday life prompted panic buying and hoarding of any goods available, which aggravated the shortages. Constant improvisation was essential to develop methods and means of supply through family, friends or new acquaintances to secure needed goods. Consumer practice changed to provide for essential needs, particularly for those lacking the wealth and time needed to seek supplies outside official markets. Second, for the Vichy regime, fixing prices and controlling the allocation of goods became a paramount concern. The legitimacy of the new French state depended on its ability to protect its citizens and negotiate effectively to resist German demands. Third, in the market itself producers of goods and services, through the growing web of intermediaries needed to connect goods and purchasers, found that scarcity and controls provided both challenges and opportunities. Being able to locate, purchase and transport goods took on far greater importance and value, and the ability to move goods outside state control offered substantial profit.

Food access became the critical realm for everyday black-market use. The condition fundamental for successful food rationing in Britain and the United States was to have sufficient supplies available to guarantee an adequate minimum diet. ‘If the assured supply is not forthcoming, all the bother is for nothing.’Footnote 7 In France, official rations promised food sufficient for slow starvation, and too often failed to deliver even that. Consumers had to find food. ‘All the bother’ in French supply management fostered evasion and hostility to state control. Official markets lost supplies to an alternative economy of barter, bonus payments, and buying from friends, shops, and new intermediaries at prices and in quantities higher than those allowed by state controls.

Black markets are delimited by the state rules for legal market transactions: increased regulation narrows the range for legal commerce and requires means of enforcement. Buying bread fresh from the oven, for example, or an extra loaf, or white bread or croissants for a family breakfast, was no longer allowed as of 1 August 1940.Footnote 8 The controls outlawed practices that had been normal, and the restrictions provided both opportunity and incentive for buyers and sellers to replace lost goods and income through illicit activity. The black market attracted sustained public attention. Consumers needed it and were dismayed by its effects. The state’s imperative to repress black markets required a major effort to persuade the public. The new regulations needed legitimacy in terms of their perceived outcomes: they had to be seen as effective and fair. To persuade the public that state policies were necessary and effective, the state publicized the abuses and the profits of black marketeers and the punishments in order to deter consumers and would-be trafiquants from black-market traffic.

Contemporaries explained black-market activity based on their experiences with shortages and the control administration. Black markets obviously provided goods to those able to pay higher prices, but it wasn’t clear whether illicit exchanges were in fact markets (‘the black market is less and less a market, and more and more black’), as prices were not determined by open competition.Footnote 9 This was true of the prices set by the state in official markets: some saw the black market as the revenge of free market forces, countering state interference.Footnote 10

The explanations for the black market immediately after the war emphasized the shortages and state policy. Michel David, writing in 1945, saw the black market as a natural consumer response to shortages which, combined with poor regulation, had encouraged illicit commerce: ‘The fisherman, the farmer, the worker, the civil servant, the mother, all of them have trafficked, often innocently, in the black market, in protesting against its demands, but in buying, selling or exchanging everything within their reach.’ David noted that the black market had victims as well, and he concluded that it had enriched a handful of profiteers and impoverished the nation.Footnote 11 Louis Baudin, surveying French economic experience, devoted a long chapter to explain how shortages and state controls had created a defective system. Spontaneous consumer actions ‘corrected’ the defect by using barter, new personal connections, and the black market, which was a necessary evil amplified by poor state policies: ‘Man is not a saint; when he suffers, he cares little for the rules.’Footnote 12

Jacques Debû-Bridel, in 1947, saw the black market as more sinister. Initially a product of military supply management in 1939, it developed through Vichy collaboration with the German ‘suction pump’ set up to drain the French economy of resources. Debû-Bridel recognized the need for a patriotic grey market (marché gris) to serve French interests, in contrast to the black market supplying Germany with Vichy’s help. Having been in the Resistance and served on a departmental committee to confiscate illicit profits, he believed Vichy personnel and administrative practices had been kept in place after Liberation. A corrupt national administration not only tolerated, but also profited from the controls and diversion of goods that sustained the postwar black market: ‘The black market, it’s the state.’Footnote 13 Yves Farge, a Gaullist, Commissaire de la République for the Lyon region after Liberation and Minister of Food Supply for most of 1946, also blamed official corruption. The black market had originated as resistance but evolved as a system for corrupt practice protected by officials in government and the judiciary, an ‘administrative organization of fraud’. Like Debû-Bridel, he saw black market use as an infection, transmitted throughout the economy and abetted by the state administration.Footnote 14

The officials enforcing state controls told a different story. Jacques Dez worked for the Contrôle économique (CE) during the war and completed a dissertation on price controls in 1950. He criticized all previous accounts of the black market as written ‘with no concern for objectivity’, especially Debû-Bridel, and he faulted their condemnations of the state and the control administration. For Dez, the black market originated in producers withholding goods from official markets to sell for higher profit. Effective price control had been frustrated by tolerance for abuse in government departments other than the ministry of finance (that oversaw the CE).Footnote 15 French finance officials recognized the importance of German black-market activity in their evidence gathered for the Nuremberg trials.Footnote 16 In 1950, they published an article on ‘The German black market in France’ in a special issue of the Cahiers d’histoire de la guerre on the German exploitation of the French economy. This distilled CE observations of German clandestine purchasing, against which they had been virtually powerless. German black-market operations took place in addition to their requisitions and official purchasing, had been practiced by all German services in France, and relied on the complicity of French trafiquants whose ‘great familiarity with the national market’ assisted in this pillaging of French resources. Implicitly, the Contrôle économique bore no responsibility for this black-market activity. The standard Ausweis (pass) carried by German transport vehicles stated: ‘the truck cannot be checked or even stopped by the French police. Any attempt to do so will be severely punished.’Footnote 17

Another controller, Raymond Leménager, defended the CE in a 768-page manuscript prepared for the Direction générale des prix et des enquêtes économiques. He gave a detailed account of the development of controls and their administration, focused on price controls, not the black market. Leménager described the CE challenges in enforcing incoherent legislation, their insufficient staff and resources, and the pervasive and perverse interference by the Germans. The exceptional circumstances of the German Occupation and exploitation made effective price control impossible. The black market thrived as a vital alternative to provide essential goods, but it fulfilled these needs ‘in the most iniquitous way, rationing by money ruled’.Footnote 18 This was precisely the result that the economic controls were supposed to prevent.

These authors’ professional training and experience structured their accounts. They agreed on the importance of German black-market purchasing and interference in French control enforcement. They differed on the degree to which bad policy, state incompetence, and corruption had aggravated the shortages, inequities, and price inflation. They noted the incoherence of state policy, lopsided enforcement and the popular alienation from policies and police that failed to control prices and provide equitable access to scarce goods. The state had focused too narrowly on catching and punishing the small fry, while major profiteers went free, with the state sometimes complicit in their illicit traffic. The social and cultural dimensions of black-market activity, essential as context, went unremarked; as did the black-market growth to serve communities of interest when the state failed to manage supplies, and when state controls and controllers lost legitimacy.

The two most influential works about the black market in Paris appeared in the 1950s: Jean Dutourd’s novel Au bon beurre (1952), depicting the black-market profiteering by a dairy shop owner and his wife, and Claude Autant-Lara’s film La traversée de Paris (1956), following two porters’ misadventures crossing Paris at night, lugging suitcases of freshly butchered black-market pork. Both works were products of resentment and frustration.Footnote 19 Meanwhile, survey histories gave, at best, passing attention to black markets, acknowledging that the activity was widespread and engaged almost everyone, with wide variation depending on a person’s wealth and location. Black markets benefited the farmers and the rich, earned extraordinary profits, and demonstrated ineffectual surveillance and corruption in the state regulation of markets.Footnote 20 Economic historians, by contrast, gave black markets little attention.Footnote 21

Jacques Delarue’s Trafics et crimes sous l’Occupation (1968) marked a notable exception. Delarue drew from his experience in the Police judiciaire to shed light on dark aspects of the Occupation – French complicity in German black-market activity, the destruction of the Vieux Port in Marseille in 1943, and the murderous path of the SS division Das Reich in June 1944. His account of the black market revealed the thorough integration of French trafiquants in the German exploitation of French resources. Delarue stated that black-market experience was the most persistent dimension of Occupation experience and memory in France. Of all the key words of the Occupation, ‘the term “black market” is without doubt the one that has remained engraved in most memories’. He focused not on the everyday, small-scale black market with which most people engaged, but on its underbelly, les dessous du marché noir that worked with French organized crime (the ‘milieu’) and operated with German approval.Footnote 22

Since the 1980s the reorientation of Vichy research has given greater attention to the social and cultural dimensions of Occupation experience, often in regional studies, and has drawn on newly available archival evidence to deepen our understanding of the context for and the local adaptations to the Occupation. Coping with shortages, particularly in food supply, was vital. Local economies, their provisioning and their adaptations to use black markets, demonstrated the normalization of illicit transactions. In agriculturally rich regions like Normandy and Brittany, black marketeers sought out farmers and competed for their produce. In the cities and in regions of monoculture in southern France, efforts to import food supplements fostered new strategies to meet consumer needs. Research organized by the Institut d’histoire du temps présent detailed the experience of shortages at the regional and departmental levels, differentiating the departments according to food supply – abundance to feed other regions, penury, and those with a rough balance able to feed their residents.Footnote 23 English-language historians gave new attention to black markets as a means for survival in regional studies; most notably Lynne Taylor’s work on experience in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais.Footnote 24 French local studies provided valuable details on consumers’ and manufacturers’ reliance on illicit trade.Footnote 25

The first national study of the black market in France based on archival research, Paul Sanders’ Histoire du marché noir, 1940–1946 (2001), showed the wealth of information now available in diverse state archives: the ministry of finance (and the Contrôle économique), justice, and the Gendarmerie, and the German military archives.Footnote 26 Sanders distinguished between the black market for essentials, especially food, in which almost everyone in France took part, and a professional black market (‘marché noir du métier’) that supplied the Germans and French industry. He stressed the importance of German purchasing and critiqued the linkage of black-market activity with Resistance.Footnote 27

Fabrice Grenard’s La France du marché noir (2008) provided a more comprehensive chronology and analysis, with thorough archival research to analyse the legislation defining black-market activity, the logic and strategies employed by trafiquants, the public perceptions and participation in black-market activity, and the enforcement challenges faced by state agencies, especially the Contrôle économique.Footnote 28 Like Sanders, Grenard distinguishes between differing motivations and logic for black-market use, developing a more complex analysis: a black market linked to subsistence (consumers and agriculture); a black market of adaptation to economic constraints (industry and commerce); a black market for profit and speculation (intermediaries); and a black market of solidarity on the part of all those not recognized or favoured by the Vichy regime (Jews, réfractaires avoiding the labour draft, and clandestine members of the Resistance).Footnote 29 Grenard has also contributed detailed black-market studies to the series of conferences organized by the CNRS research group GDR 2539 on the theme ‘French business during the Occupation’. This group, under Hervé Joly’s direction, encouraged new research on business histories during the Occupation, including the experience of workers, consumers, specific firms and industrial sectors, and presented research findings in a series of conferences from 2002 to 2009.Footnote 30

In this same period, new research on black markets elsewhere in Europe during the Second World War has improved our knowledge of the pervasiveness of black markets and their importance in consumer and producer adaptations to shortages. Black markets developed as a means of exploitation by the German administrative regimes in Occupied Europe, and as a means of resistance and survival by oppressed populations. Even in Britain, with no German occupation but facing serious material shortages, and in Germany itself, exploiting wealth from the countries it had conquered and imposing harsh penalties on domestic black-market activity, black markets produced economic, social and cultural changes. Shortages impacted everyone. Black markets were a direct response to shortages and the economic controls devised to manage their impact.Footnote 31

The Black Market

Illicit activity, often unrecorded or disguised, became a critical part of everyday life. Shannon Fogg, studying how the rural population in the Limousin region dealt with the material shortages that dominated their lives, found that behaviour changed throughout the community in a ‘banalization and normalization of illegality’.Footnote 32 This had far wider influence than the ‘outlaw culture’ in the Resistance described by Roderick Kedward; it spread throughout French consumer practices without regard for politics.Footnote 33 This normalization of illegality, an essential element in the development of strategies to cope with shortages, is central to Marché Noir and my analysis of the purposes black markets served and the reasons for their power, prevalence and persistence.

My approach in Marché Noir is organized by sectors of economic activity, to provide clear analysis of the logic for and the impact of black-market activity in each kind of activity. The sectoral differences in needs and in demand for goods influenced the availability and the necessity for black-market goods. Local communities and the resources available within them became intensely important for how individuals adapted behaviour during the Occupation and demanded retribution after Liberation.Footnote 34 Strategies for survival are a recurrent theme. As Tatjana Tönsmeyer notes, in a volume on food shortages under German occupation, attention to ‘coping strategies’ is essential to understand wartime experience.Footnote 35

Marché Noir addresses key issues in the economic and social adaptation to wartime shortages, the development and use (and abuse) of state policy, and conflicts between state authority and the interests of producers, shopkeepers and consumers. The first and most obvious issue is the need to evaluate the role of state policy and its impact on market activity. All states used price controls and rationing to contain inflationary pressures, to allocate materials according to priorities for the war effort, and to distribute scarce goods more equitably among consumers who would otherwise bid against each other. Otherwise, the wealthy would maintain or increase their prewar consumption at the expense of those lower on the income scale. France offers a complicated case in which the controls were extensive, convoluted, and increasingly contravened and ineffective. The presence of a ‘national’ government in Vichy meant that French officials implemented this regulatory regime. The growth and the importance of black-market activity in France demonstrated the failure of Vichy’s control regime and the loss of legitimacy for controls, controllers and the state itself. The handbook prepared for Allied troops who would land in France put this bluntly: ‘The unsuccessful campaign to suppress the black market affords the most extreme example of the inefficiency, the division and overlapping of responsibility and the proliferation of governmental agencies which are so characteristic of the Vichy régime.’Footnote 36 Chapter 3 provides a critical evaluation of the operations of the main enforcement agency, the Contrôle économique.

When controls work well, minimal enforcement should be needed. Market players engaged in buying and selling will support controls they see as fair, useful and legitimate. W. B. Reddaway wrote of wartime rationing in Britain that success and the avoidance of a black market depended upon designing a system ‘relatively easy to enforce, and which will, indeed, to a large extent “enforce itself”’.Footnote 37 The French control system did not enforce itself: it became a target for protest and sometimes violent aggression by its intended beneficiaries. The degree to which market players support regulation and regulate their own conduct is critical to maintaining order in a liberal society. The more controls are seen as pernicious, the greater the policing power needed to enforce them. Resistance to state authority can take many forms, and the black market offers an opportunity to study and reflect on the state’s ability to manage economic conduct by observing French experience ‘at the grass-roots level, among those whose fight was located in the fine meshes of the web of power’.Footnote 38 Food protests and consumer resistance are covered in Chapter 6; attacks on controllers in Chapter 8.

The importance of regulating behaviour and adapting institutions to govern economic conduct is essential to understanding black-market use as social and economic behaviour. The shock of defeat and occupation in 1940 reversed the long-term evolution of state controls towards greater market freedom. With the ensuing shortages of material goods, the state introduced not only new rules, but new policing agencies to enforce rules and contain market disorder. The changes in conduct and the alienation of support for controls show how rapidly the initial public support for effective regulation was disappointed. Managing shortages of essential goods had been a longstanding function of state authority; in times of famine, the eighteenth-century state had served as ‘baker of last resort’.Footnote 39 How the French state failed in this role during the Occupation and the immediate postwar years provides grounds for reflection on the power of the state and the limits on its power to regulate markets.

The second issue is the dynamic for black-market growth. Chapters 4, 5 and 6 look at the practical problems and the incentives for black-market development in agriculture, industry and commerce, and consumer strategies for survival. The scale of black-market activity in France was not a product of greed alone. Rational economic choices underlay decisions about what goods to produce, where and how to distribute them, and who would have access to purchase them. The massive demand, the enormous purchasing power available in France – especially in German hands – and the needs of diverse consumers created an array of market incentives that worked outside the official markets with its prices and rations fixed by the state. The demand and the potential for profit incentivized entrepreneurial problem-solving that migrated substantially from official to clandestine markets.

Consumer vulnerabilities and resistance, and strategies for provisioning and survival, are a third key issue. The politics of everyday life in conditions of adversity include consumer willingness (or not) to tolerate controls and their alternative strategies for provisioning. Consumer tactics of consumption under adverse conditions have a political content that can challenge the structures of power in government, markets and the production and delivery of goods.Footnote 40 The exchanges negotiated outside state rules, to the mutual benefit of buyer and seller, constituted a recovery of some consumer agency in a system of constraint. The study of everyday life under coercive regimes has become increasingly important in understanding how power is exerted and resisted in the social and economic realms, especially in times of stress and under authoritarian regimes. Historical study of popular adaptations to survive shortages has discounted the degree to which states exert ‘totalitarian’ power under Nazism, Fascism and Stalinism, and recognized the agency of ordinary citizens and their ability to exploit gaps in the regimes of control and use regime rhetoric to counter the power of the state apparatus.Footnote 41 Ordinary consumers and their routines of daily life in extraordinary circumstances allow us to see the rigidities in state power and the flexibility of popular resistance by non-political agents whose ideals and values are expressed in actions rather than words. Even those most willing to believe in Vichy’s proclaimed values of ‘work, family and fatherland’ adopted survival strategies that weakened support for the regime and undermined the values Vichy claimed it would restore.

One revealing dimension of Vichy’s failures, discussed in Chapters 7 and 8, was the result of its effort to establish a ‘moral order’ in France. The everyday realities of shortages and the normalization of illegality made many observers, particularly state officials, fear a national decline in moral standards. Wartime prefects and post-Liberation Commissaires de la République warned of a ‘profound moral crisis’, demonstrated by the increased theft, the active black market, and the preference of youth for the easy profits of crime over honest hard work.

The fourth issue is that of social fracture in time of economic stress. Economic controls were supposed to share the sacrifices imposed by economic contraction and German exploitation to equalize the burden. Marshal Philippe Pétain explained food rationing in October 1940 as a ‘cruel necessity’, imposed by the defeat, in the face of which ‘we want to assure the equality of all in making sacrifices. Each must take their part in the common hardships, without allowing some to be saved by their wealth and impose greater misery on the others.’Footnote 42 But an equal sharing of misery was impossible. On the vital matter of food rations, consumers were organized in categories by their needs according to age, work and gender (with extra food for pregnant and nursing mothers and babies), which assumed equal needs within each category as a matter of convenience. (The rationing system is explained in Chapter 2.) Needs within categories were not identical, and the categories and registrations became opportunities for fraud. Beyond the problem of categories, access to goods varied not just by income (whether one could afford the black market), but also by proximity to goods, which varied by region, occupation, social status and personal connections. The Contrôle économique claimed that price controls were essential in order ‘that relations between French people not be ruled by the law of the jungle, and to save the weak from being sacrificed for the benefit of the strong’.Footnote 43 Inept controls transferred output and consumption to black markets, where ‘the law of the jungle’ increased the power of the wealthy.

The two most notable fractures in access to goods were between the rich who could afford black-market prices and the middle and working classes who could only rarely do so, and between urban residents needing food and rural populations. In both rural and urban experience, there were also profound differences between productive polycultural regions and those heavily committed to a single-product monoculture. Police and prefects reported frequently on the gap between the rich and the rest, a division into ‘two distinct clans’ one of which could provision itself normally in using the black market, the other – the middle and working classes – lacking essential goods.Footnote 44 Rather than equality, state rationing established a control system that was inconsistent (varying in degrees of control) and corrupt, increasing popular belief in unequal treatment. Prefects in departments with strong agricultural sectors complained of peasant greed: ‘Unfortunately, the knowledge of privations on the part of those in cities, notably the factory workers, leaves the peasant indifferent. A selfish materialism continues to rage in the countryside.’Footnote 45 Such differences fuelled deep animosities and social divisions during the Occupation, and demands for retribution when Liberation released local residents from the constraints of state control.Footnote 46 In the postwar economic purge, covered in Chapter 9, many black-market profiteers seemed, to the citizens they had exploited, to escape punishment. The breadth of the black market and its ‘essential’ nature for survival made postwar justice appear flawed: black-market practices continued, some newly re-legalized, and the state opted in 1947 for fiscal measures to tax rather than punish the actors and activities needed for reconstruction.

To thrive as it did in France, the black market needed to escape disruption and suppression by the state: it sought invisibility. The Contrôle économique observed in 1945: ‘Its essential characteristic is to be very hard to pin down, it leaves no accounts and can only be proven in starting from very slight evidence.’Footnote 47 The archival documentation for black-market activity comes mainly from state efforts at repression. Particularly important in France are the records of the Contrôle économique, supplemented by judicial and police records, prefect reports, and the contemporary press. Some writers showed astute observation and penetrating analysis of black-market operations and the difficulties they posed for suppression. The language in their reports reveals rising frustrations in combatting the spreading and effective social resistance to officials and economic controls.

The nature of this evidence and its bias, in recording the suppression of illicit activity, leaves many elements of that activity obscured, but it allows for analysis of the origins and the dynamics of black market growth as an essential part of the survival strategies of those adapting to economies of constraint (producers, consumers, and those engaged in the commerce connecting them): constraint by the shortages of goods, by tighter limits on licit commerce, and by controls to contain prices and distribute scarce goods. Patrick Modiano’s father survived the war as a black marketeer. In his search for details, Modiano characterized many of his father’s associates as ‘phantoms’: ‘They are very shady travellers who pass through train stations without my ever knowing their destination, supposing that they have one.’Footnote 48

Representations of economic life in fiction, based on observations of life under the Occupation, often complement the archival evidence. As imaginative reconstructions, they do not carry the official status granted to prefects’ reports and Contrôle économique analyses (which vary widely in quality, originality of analysis, and degree of departure from formulaic response to meet official reporting requirements). But the fictions display the biases, the rancour and the hopes of French citizens adapting their behaviour to the economy of penury. This is particularly interesting after the war, when accounts of war experience were written knowing the outcomes of wartime changes. Writers try to render past experience comprehensible (events as they happen are not) and write to serve current needs, to legitimize or critique the present, and to give direction for future action. In France, reconciling wartime collaboration and submission to the Germans with the Allied victory and Liberation produced a ‘Gaullist resistancialist myth’, with de Gaulle serving as inspiration for a broad national will to resist. Twenty-five years later (Henry Rousso’s ‘broken mirror’ phase of the Vichy syndrome, 1971–1974) this resistancialist mirror was shattered by new research challenging the extent of resistance and the logic and impulse behind French collaboration.Footnote 49 Robert O. Paxton’s Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order (1972) was the key paradigm-changing book, setting a new agenda for research to understand the importance of collaborationist initiatives in France, and opening the way for a new generation of research on collaboration and compromise.Footnote 50 As elsewhere in Europe, stories constructed a ‘usable past’ to serve present concerns; to recover and move on from the tragic experiences in war.Footnote 51

For France, until the 1990s, that usable past gave little attention to the black market, which owed so much to the conditions of penury and exploitation imposed by the Germans and was linked in its worst cases to collaboration and brutal exploitation. The breadth of illicit exchange and improvisation was less visible; its very breadth made it less spectacular. But the details and logic reveal a black-market experience that was more complex, more controversial, and more important than had been recognized, as an essential element in economic survival.