There are no rights without remedies, but as socio-legal scholars have long recognized, to provide remedy, institutions must be activated by those seeking to protect and advance their rights (Zemans Reference Zemans1983). Under what conditions will people be willing to turn to the state to make a formal claim when facing a rights violation? The legal consciousness literature offers diverse explanations. Some works emphasize the importance of quite fixed factors to perceptions of and responses to rights violations, such as structural position (Gloppen Reference Gloppen, Gargarella, Domingo and Roux2006; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2000; Reference Nielsen2004; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2008; Taylor Reference Taylor2020) or an entrenched cultural or ideological context (Haltom and McCann Reference Haltom and McCann2004; Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022; Levitsky Reference Levitsky2008). Others underscore that people’s willingness to pursue remedies is neither structurally determined nor static, but is, rather, “fluid, flexible, dynamic, and subject to multiple constructions and … reconstruction” (McCann Reference McCann, Fleury-Steiner and Nielsen2006: xiii; Fleury-Steiner and Laura Beth Nielsen Reference Fleury-Steiner and Laura Beth Nielsen2006). They argue that the intensity or urgency of the grievance (Kritzer Reference Kritzer, Cane and Kritzer2010; Hendley Reference Hendley2012; Taylor Reference Taylor2018; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2023), as well as social experiences and political interventions, can motivate and equip underprivileged people to make formal rights claims (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006; Hernandez Reference Hernandez2010; Lake et al. Reference Lake, Mukatha and Walker2016; Tait Reference Tait2021; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2023; Taylor Reference Taylor2023). Among such experiences, participation in a social movement has been shown to leave a mark on the legal consciousness of the individuals involved, altering the way that activists understand themselves as rights bearers, even if the movement does not succeed in achieving favorable court rulings or policy change (McCann Reference McCann1994).

What happens, then, when, in a highly unequal but stable democratic society known to have low levels of rights consciousness and claiming, a diffuse popular mobilization challenges the state’s fundamental normative framework and demands justice and rights for long-excluded sectors of the population? In such a context of widespread citizen engagement and collective claim-making, what can we learn about the factors that affect perceptions of and responses to rights violations at the individual level?

In this article, we offer insights on these matters from an original, nationally representative (telephone) survey conducted at the height of a “broad and all-encompassing” sociopolitical mobilization (Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara Reference Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara2020) in Chile, a stable democracy in which, aside from elections, political participation was limited, de jure by a rigid constitution that entrenched neoliberalism and established a minimal state and de facto by persistent and severe inequality (Corvalán and Cox Reference Corvalán and Cox2013; Couso Reference Couso2011; de la Maza Reference de la Maza2014; Posner Reference Posner2008; UNDP 2014). Chilean citizens were socialized to fend for themselves or to seek help from private sources (Araujo and Martuccelli Reference Araujo and Martuccelli2012), and scholars have found that they exhibit limited knowledge and capacities to claim rights (Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022). Then, in October 2019, mass protests against inequality, discrimination and sociopolitical exclusion erupted across the nation, lasting for several weeks. These were met with significant police brutality, documented and denounced by national and international human rights organizations (Human Rights Watch 2019). A key demand of protestors was a democratic path to replace the neoliberal constitution inherited from the 1973–1990 military dictatorship, to which political authorities acceded. Suddenly, after decades of imposed political slumber (Heiss Reference Heiss2017),Footnote 1 average Chileans had the opportunity to participate, via formal and informal mechanisms, in a bottom-up effort to refound their political system. Citizen meetings, known as cabildos, proliferated, and universities, civil society associations and municipal governments began holding informational meetings on a wide range of constitutional matters. In an October 2020 plebiscite, Chileans voted overwhelmingly to proceed with constitutional rewrite and to do so through a specially elected convention, whose members were elected in May 2021 and who worked from July 2021 through July 2022.Footnote 2 In sum, over the course of 18–24 months, Chilean society underwent a collective clamoring for justice, which began with mobilization from below that was unprecedented in the post-Pinochet era and evolved into a bottom-up effort at constitutional refounding.

It was at the peak of this moment of high social mobilization, in which justice, rights and citizenship became the focus of everyday discussion on the streets, in neighborhood gatherings and in the media, that we fielded our survey to probe perceptions of and responses to two hypothetical rights violations that were both salient during the popular mobilization (discrimination in a public health clinic and police brutality). In addition to testing competing relationships identified in previous studies on legal consciousness (such as sociodemographic characteristics, people’s understandings of rights violations, perceived knowledge of their rights, expectations about the outcome of the scenarios and previous experience with state institutions, including courts), we also asked respondents questions about their participation in the mass mobilization.

Our analysis found no statistical relation between structural position (socioeconomic status, gender or indigeneity) and stated willingness to claim in either scenario. Despite the many, often intersecting, disadvantages that women, indigenous persons and lower-income people face in Chile, members of these marginalized groups are no less likely than more privileged respondents to say they would make a formal claim when faced with discrimination or abuse by a state actor, as some literature might lead us to expect (e.g., Nielsen Reference Nielsen2004). Instead, across the two scenarios, our analysis found only two variables to be statistically related to an individual’s professed willingness to make a formal claim: self-perceived knowledge of where to turn to file a claim in the situation, which captures internal efficacy, and self-reported participation in the mass protests in late 2019 and early 2020, which means that the a priori likelihood of seeking remedies for state abuses through institutions is higher among those individuals who mobilized for justice on the streets.

With these findings, our study offers several insights of relevance for debates on the factors that shape legal consciousness and, with it, rights claiming. First, it reinforces the finding of several prior works across different democratic settings that structurally disadvantaged people are as motivated to make claims on the state as their more privileged compatriots (Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022; Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018; Merry Reference Merry1990). Second, it draws attention to the connection between self-perceived practical knowledge about where to seek remedy and an individual’s inclination to make claims. Rather than rights consciousness and self-perceived knowledge of rights (neither of which was statistically significant in our models), our findings suggest that when a person experiences a harm or abuse, a key contributor to proclivity to claim is their sense of internal efficacy, that is, their self-assessed knowledge of where to turn in a given situation. This is consistent with prior studies on access to justice and legal empowerment and suggests that programs and policies designed to enhance the internal efficacy of all people have the potential to make a difference in advancing access to justice and increasing political equality, in Chile and beyond (Gramatikov and Porter Reference Gramatikov and Porter2011; Hernandez Reference Hernandez2010; Hilbink and Salas Reference Hilbink, Salas, Davis, Kjaerum and Lyons2021; Pleasance and Balmer Reference Pleasance and Balmer2014; Tait Reference Tait2021).

Third, our results point to a possible link between participation in protests around rights and justice and individual proclivity to claim rights. While socio-legal scholars have studied the ways that collective social mobilization affects individual legal consciousness and mobilization among social movement members (McCann Reference McCann1994; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2018), our study brings questions about individual legal consciousness to the context of mass social and political protests. Our finding at the national level that participation in protests is statistically related to an individual’s stated willingness to make a formal claim in response to a rights violation merits further investigation to determine if and how the two are causally related, a matter of interest both to law and society scholarship and to theorists of political participation (Aytaç and Stokes Reference Aytaç and Stokes2019; Booysen Reference Booysen2007; Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, Kruks-Wisner and Taylor2024; Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018; Taylor Reference Taylor2020).

Situating the study in the literature on legal consciousness and claim-making

Studies in the socio-legal literature have long sought to understand the factors that lead those who experience harms and abuses to “name, blame and claim” these as legal rights. Based mainly on the U.S. case (and to a lesser extent on the U.K.), scholars have focused on people’s responses when they confront justiciable events. This type of event is defined as an experience which raises legal issues, regardless of whether it is recognized by the individual as “legal” and the type of action they take to deal with it (Genn and Beinart Reference Genn and Beinart1999: 12). In doing so, scholars have decentered the analysis from courts and have turned to study the process of dispute transformation. This is the process by which “unperceived injurious experiences are – or are not – perceived (naming), [and] do or do not become grievances (blaming) and ultimately disputes (claiming)” (Felstiner et al. Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1980: 631).

One longstanding and often empirically supported argument is that structural disadvantages systematically impede the process of dispute transformation (Gloppen Reference Gloppen, Gargarella, Domingo and Roux2006; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2000; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2008; Taylor Reference Taylor2020; Zemans Reference Zemans1982). The reasons are quite intuitive: in addition to material advantages, those with higher socioeconomic status, education, and/or racial and gender privilege will conceive of themselves as legally entitled rights bearers and frame their problems in rights terms, while marginalized people likely will not (Abrego Reference Abrego2011; Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Buck, Patel, Denvir and Pleasence2010; Bumiller Reference Bumiller1987; MacDonald and Wei Reference MacDonald and Wei2016; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2000; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2008; Taylor Reference Taylor2020). Moreover, people of color, the poor and those living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to lack trust in state institutions due to negative experiences with them (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2004) and will be inclined to “lump” their problems (Engel Reference Engel2010) or turn to family members, neighbors or self-help rather than to expend their limited resources appealing to untrusted legal institutions (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Felstiner Reference Felstiner1974; Levine and Preston Reference Levine and Preston1970; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2004).

While few analysts question the relevance of structural position for legal consciousness and rights claiming, numerous works have shown that structural disadvantage does not translate inevitably to resignation in the face of injustice. Merry’s (Reference Merry1990) seminal study of legal consciousness among working-class Americans in Massachusetts, for example, argues that people take their problems to courts because of a consciousness of rights and a sense of entitlement: “Despite their recognition of their unequal power, they nevertheless think they are entitled to the help of the court [as members of a legally ordered society]” (2). Moreover, in a variety of settings, including China (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006), the Democratic Republic of Congo (Lake et al. Reference Lake, Mukatha and Walker2016) and South Africa (Tait Reference Tait2021), other scholars have shown that micro-level experiences with courts, guided by legal aid, can influence disadvantaged people’s perceptions of themselves as legal agents and of the appropriateness and value of making claims on the state. Such experience can even be “transformative,” giving disadvantaged people a “new sense of empowerment” (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006: 807) and a determination to turn to the law again in the future, despite disappointment and frustration with how the system works.Footnote 3

Another widespread finding is that the likelihood of making claims and asserting rights depends on the nature of the legal need, in particular, its urgency or intensity (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Buck, Patel, Denvir and Pleasence2010; Engel Reference Engel1984; Genn and Beinart Reference Genn and Beinart1999; Hendley Reference Hendley2012; Reference Hendley2017; Kritzer Reference Kritzer, Cane and Kritzer2010; MacDonald and Wei Reference MacDonald and Wei2016; Silbey Reference Silbey2005; Taylor Reference Taylor2018). Hendley, for example, argues that ordinary Russians decide whether or not to go to court based on a calculation of the stakes as well as their sense of the odds of victory (Reference Hendley2017), while in an analysis of the persistent mobilization by family members of the disappeared in Mexico, Gallagher (Reference Gallagher2023) traces how the life-shattering nature of a loved one’s disappearance spurs shifts in legal consciousness and claiming, even in a context of low state responsiveness.

A different set of studies on legal consciousness and claim-making examines how “broader society-wide dimensions of collective life [or] ‘macro-contextual factors’ … shape subjectivity and practical activity” (McCann Reference McCann, Fleury-Steiner and Nielsen2006: xxv). For example, Levitsky (Reference Levitsky2008) contends that the dominant model of private (family or market) responsibility for health care shapes, and ultimately limits, the way Americans perceive injuries and imagine solutions thereto. Comparative scholars, for their part, have illuminated the differences in perceptions and/or responses between individuals from similarly situated social groups in distinct macro-political contexts. Through focus groups in Chile and Colombia, for example, Hilbink et al. (Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022) find that although people across countries and social groups are inclined to engage the justice system to make claims in the face of harms and abuses, disadvantaged Colombians exhibit much greater rights awareness and familiarity with where and how to seek institutional remedies than do their Chilean counterparts. They attribute this difference to macro-level “political and institutional differences between [the two countries], such as rights education and legal literacy campaigns and policies in Colombia, versus their almost complete lack in Chile” (22). To be sure, Taylor (Reference Taylor2023) illuminates how, following the introduction of the new Constitution in 1991, such campaigns and policies transformed the legal consciousness and claim-making of ordinary Colombians around social rights (see esp. Ch. 4).

Such a reshaping of legal consciousness has also been traced among social movement activists, emerging from their experiences in the movement’s legal practices, strategies, campaigns and framings (McCann Reference McCann1994; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2018). For example, in his classic study on the pay equity movement in the United States, McCann argues that one of the main consequences of the movement was the empowerment of female activists. The campaign “was about treating women as human beings with rights” and “the women involved with this issue … became so much stronger personally,” experiencing and expressing a “dramatic increase in confidence and competence – what we might call citizen efficacy” (259).

Could a more diffuse and broad popular mobilization, propelled by grievances about structural inequalities and disseminating new narratives about citizens’ entitlements and the effectiveness of their political engagement, have similar consequences among the general population and particularly among marginalized sectors of society? Might different forms of participation in the mobilization affect people’s proclivity to seek remedies for publicly salient rights abuses? Or are variables unrelated to participation in the mobilization, such as structural position, experiences with claiming or expectations about outcome, correlated with people’s willingness to claim their rights at such a moment? In this study, we explore these questions by analyzing data gathered in Chile at a time of intense social effervescence and proliferating efforts at political re-imagination, in which many who had lost confidence in the political system started calling for a new social contract between the state and society (Heiss Reference Heiss2021; Somma Reference Somma2021).

Mass social and political mobilization in Chile

In late 2019, Chile’s stable democracy was rocked by weeks of massive protests against inequality, exclusion and perceived systemic injustice. Day after day, hundreds of thousands mobilized across the territory, and on October 25, the country experienced “the biggest march” since the return of democracy, in which more than 1.2 million people participated in Santiago alone (Sherwood and Ramos Miranda Reference Sherwood and Ramos Miranda2019).Footnote 4 Alongside the protests, citizens convoked hundreds of town hall-type meetings (cabildos) around the country, focusing on different themes: e.g., inequality in accessing basic services such as education, health and housing, environment, gender issues and constitutional change.Footnote 5 Indeed, constitutional replacement crystallized as an important demand of the uprising, in order to clear the way for more redistributive policies and greater government responsiveness.

Such a widespread social mobilization occurred unexpectedly in a country in which opportunities for citizens to participate in politics were limited both institutionally and socially. As is well known, between 1973 and 1989, Chile experienced a military dictatorship led by Augusto Pinochet, characterized by massive human rights violations and the introduction of a radical neoliberal socioeconomic model. This model, which was institutionally entrenched in the 1980 Constitution (Brinks Reference Brinks2012; Couso Reference Couso2011), shrunk the size and role of the state by privatizing the provision of basic social goods (e.g., education, health, social security and water) and atomized civil society (Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara Reference Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara2020; Araujo Reference Araujo and Araujo2019). Although, following the transition, democratic authorities gradually introduced social policies to help decrease poverty, high levels of socioeconomic inequality persisted. Chile’s 2020 Gini coefficient was 53, with the top decile drawing 37.2% of the income share and the lowest decile earning 0.1% (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social 2021). Chile’s capital city, Santiago, where close to 40% of the country’s population lives, is one of the five most unequal cities in Latin America (U.N. Habitat 2010). Before the pandemic, for example, in Vitacura, a municipality in the northeast area of the city, 2.8% of the population was living in poverty, while in La Pintana, a municipality in the south of the city, 42.4% lived in such a situation (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social 2018).

All of this has had long lasting effects in social relations and in how individuals conceive their social identity. The neoliberal model imposed in Chile introduced institutional norms that aimed to neutralize political action and collective identity formation, redefining the role of politics and its potential as a collective activity for social change (Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara Reference Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara2020: 17 and 24). By reducing the role of the state in provision of socioeconomic rights, this model has promoted a culture of self-management where individuals are required to address the gaps it creates (Ortiz Reference Ortiz2014). Several studies have evidenced the introduction of a logic of competition in social relations among Chileans and a perception that individuals are responsible for their personal well-being, bringing in an individually based approach to resolve problems in light of a perceived absence of institutional support and a feeling of being abandoned to their own personal effort (Araujo Reference Araujo and Araujo2019: 18 and 23; see also Araujo and Martuccelli Reference Araujo and Martuccelli2012; Huneeus Reference Huneeus and Sagaris2007; and Moulian Reference Moulian2002). In addition, some works have shown that Chileans display a low awareness of their legal rights and what procedures to follow in case of rights violations (Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022), as well as a weak association between rights as ideals, on the one hand, and rights activation through formal complaints and requests, on the other (Araujo Reference Araujo2009).

In this setting, the protesters themselves described the 2019 social uprising as a “citizen awakening” (Taub Reference Taub2019). At the time, observers noted that “a shift has occurred in the manner in which Chileans understand themselves and their place within the community […] the notion of community, of ‘people,’ no longer seeming an unintelligible chimera” (Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara Reference Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara2020: 36). As another analyst put it, protesters “do not want a revolution, they want to call attention to and have their demands attended to;” “what this new social agent demands is a reformulation of the model” (Jiménez-Yañez Reference Jiménez-Yañez2020). People thus perceived the constitutional process “as part of a new dynamic, one that was an alternative to traditional politics” and one in which people “would be taken into consideration, would be heard” (Sajuria and Saffirio-Palma Reference Sajuria, Saffirio-Palma and Fuentes2023: 141 and 143).

These massive protests, most of them peaceful, were met with significant police repression and human rights violations (Human Rights Watch 2019). According to Amnesty International, as of March 2021, there had been more than 8,000 victims of institutional violence and “[a]t least 347 people sustained eye injuries, mostly from the impact of pellets” (2020: 5; see also 2021) that occurred during the social uprising. This was extensively covered by the national and international press and highly criticized by the public, becoming “a rallying symbol” of protesting (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2019).

Despite these problems, Chile embarked on a process of constitutional rewrite, after congressional leaders reached a historic agreement to hold a binding, national plebiscite – the first since the return of democracy in 1990 – to decide whether and how to write a new constitution. Citizens voted overwhelmingly to approve the drafting of a new constitution through a constituent body elected uniquely for that purpose. From July 2021 to July 2022, Chile’s Constitutional Convention, which included gender parity and reserved seats for indigenous peoples, delivered to the country the first democratically crafted constitutional text in Chilean history (Hilbink Reference Hilbink2021).Footnote 6

It was at the peak of this process, in the 6 weeks leading up to the start of the constitutional convention, that we conducted our survey.Footnote 7 This enabled us to probe perceptions and responses of the public to rights violations at a moment of society-wide mobilization, exploring whether there was any relationship between participation in this collective social and political mobilization and individual Chileans’ responses to rights violations while also testing a variety of other existing arguments in the literature regarding the factors that lead people to pursue remedies.

Research design

The data for our analysis come from an original, nationally representative telephone survey conducted in Chile between May 20 and June 30, 2021. The data are based on a random sample of N = 1,067 adults (18 years and older) that live in urban areas across the 16 regions in Chile.Footnote 8 A local research firm helped us to implement the telephone survey using a sampling frame of telephone numbers (N = 9,761), representative at the national and regional levels. The sample was composed of 47.4% males and 52.6% females, and the mean age of respondents was 48 years. The survey consisted of questions about people’s perceptions and responses when facing two situations that constitute, but were not presented as, rights violations, as well as their opinions about and experiences with political and justice institutions in the country, their political participation and sociodemographic characteristics.Footnote 9

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable in this study is the professed proclivity to claim rights, which we probed by posing to participants hypothetical but highly plausible scenarios of rights violations perpetrated by Chilean state actors and asking what they would do in such situations. We described two scenarios that were very much part of the public discourse in and around the social uprising, and which, by offering variation in the type of state perpetrator and the severity of the harm, allowed us to see whether different characteristics of the offense would elicit different responses, as numerous works in the literature suggest. The first scenario described a discriminatory situation in which an individual approached the state for health care but public health staff denied the respondent service based on their personal characteristics.Footnote 10 In the second scenario, the respondent or a family member was the subject of state aggression, having been arrested and beaten by the police.Footnote 11 In each scenario, we asked people if they had experienced such a scenario and what they did or would do about it (providing up to two answers – see Table 1).Footnote 12

Table 1. Hypothetical scenarios and questions about rights claiming behavior

To capture the proclivity to claim rights, we analyze the responses provided by survey participants that reported not having experienced the hypothetical scenarios, indicating a potential future course of action. While it would be interesting to compare the group that reported having experienced the scenarios to those that have not, responses regarding what people did and what people would do about these scenarios are not necessarily comparable. In particular, while hypothetical behavior is about a prospective action, bringing to bear a person’s views and experiences at the time of the survey (captured in the survey by the question “What would you do (about it)?”), actual behavior (captured in our survey by the question “What did you do (about it)?”) is about a completed action at an unknown point in the past, potentially before the social uprising and constitutional process began in Chile. Though we recognize that people might not ultimately do what they say they would do in a hypothetical scenario (Taylor Reference Taylor2020) – indeed, while we know that a host of factors might come into play to affect their behavior in an actual situation – we posit that a person’s (a priori) proclivity to claim matters and that we gain important information by focusing on the nearly 90% of the sample who have not experienced the scenarios we present to them.

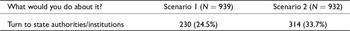

We model the two rights violation scenarios separately, and for each, we use the dependent variable “Turn to state authorities/institutions” (response category B) to capture the proclivity to use formal, institutional channels to demand redress for injuries (see Table 2). This category is distinct from the other options of doing “nothing,” engaging in vigilantism, demanding to speak to a supervisor or using non-state mechanisms such as turning to a civil society organization or to social or mass media to publicly denounce the scenario. As Kruks-Wisner argues, “Public acts of complaining by citizens are a critical but fraught form of participation. They are acts of bravery (asserting oneself in the public sphere) and of aspiration (asserting needs and interests). They are also expectant acts, which imply a sense of entitlement and of personal and political efficacy” (Reference Kruks-Wisner2021: 45).

Table 2. Distribution of dependent variable

We coded the dependent variables as binary variables in which 0 means that the survey respondent didn’t mention option B, and 1 means that the survey respondent mentioned this option. Thus, we estimate parameters using a logit model. This type of maximum likelihood estimation technique is used to model an outcome that either happened or did not happen. Using a Bernoulli distribution, we model the probability that such an event occurs Pr(Y = 1), which will be determined by a set of independent variables through a nonlinear logistic cumulative density function (Berry et al. Reference Berry, DeMeritt and Esarey2010).

Independent variables

As noted above, a common argument in the literature is that an individual’s structural position shapes their attitudes and actions when they experience legal harms. For this reason, we included the following variables: gender, self-identification with an indigenous groupFootnote 13 and socioeconomic status. We also included the age of the participants as a variable, which is particularly important in Chile because of the impact that the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship had on the life experiences of those who lived through it. To capture participants’ socioeconomic status, we use a well-established variable in social research in Chile that categorizes individuals into seven socioeconomic groups (from lowest to highest: E, D, C3, C2, C1b, C1a, AB) based on three variables and four survey questions: (i) educational background and principal economic activity of the head of the participant’s household, (ii) the total income in the household and (iii) how many people live in the house.Footnote 14 Most research recategorizes these seven groups into three or five analytical ones to conduct statistical analysis.Footnote 15 We follow such conventions and conduct models with both variables separately.

In addition, we included several questions to capture the relationship between micro-level factors and people’s proclivity to seek remedy. First, we asked the following set of questions that probe participants’ understandings and expectations about the scenarios, including two about their rights awareness and self-assessed knowledge of rights and two that are proxies for their sense of internal and external efficacy, respectively:

— “Which of the following statements best describes this situation?” This is a categorical question that offers participants the following options: Bad luck/part of life; Bad public servant; Administrative mistake; Rights violation; Other. For this analysis, we created a dummy variable (Rights violation) in which 1 = Rights violation and 0 = Any other alternative.

— “With regard to your rights in this situation, would you say that you know them very well, that you have some idea, that you have little idea, or that you do not know your rights in this situation?” (Know my rights).

— “With regard to where to turn to file a claim in this situation, would you say that you know very well where to turn, have some idea about where to turn, have little idea about where to turn, or that you do not know where to turn to file a claim in this situation?” (Know where to turn)

— “With regard to the final outcome in this situation, do you feel the outcome would be: totally just, somewhat just, somewhat unjust, or totally unjust?” (Expectation of outcome).

These three last questions have a four-point response scale (Know their rights and Know where to turn: Very well; Have some idea; Have little idea; Do not know; Expectation of outcome: Totally just; Somewhat just; Somewhat unjust; Totally unjust). Following standard practice in much survey work, we grouped the positive and negative response categories, rendering them all binary variables: For Know my rights and Know where to turn, 0 = Don’t know + have little idea and 1 = Have some idea + know very well. For Expectation of outcome, 0 = Totally unjust + Somewhat unjust and 1 = Somewhat just + Totally just.

Second, we included two binary variables to account for the role that previous experiences with state institutions could play in shaping people’s willingness to use formal channels to claim rights (0 = No and 1 = Yes):

— “In the last 5 years, have you sought to contact an authority or institution to make a request or claim other than a required procedure?” (Experience with state institutions)

— “In the last 10 years have you had to appear in any court?” (Experience with courts)

In order to assess the relationship between participation in the social mobilization and people’s proclivity to claim rights, we added two variables about their experience in the ongoing constitutional process:

— “Have you participated in a town-hall meeting (cabildo)?” and “Have you participated in an informative session about the constitutional process?”

— “Have you participated in a march related to the constitutional process?” and “Have you participated in a protest related to the constitutional process?”

For each of these two pairs of questions, we created a dummy variable (Participation in informative sessions and Participation in protests, respectively) that merged positive responses such that 1 = Has participated in at least one of these two informative meetings; 0 = Has not participated in any of them and 1 = Has participated in at least one of these two forms of public protests; 0 = Has not participated in any of them.

Findings

Preliminarily to our statistical analysis, our survey data show that the majority of participants did not say they would file a formal complaint in either scenario. This does not mean their response was they would do nothing (a response given by only 9.1% and 6.8% in each scenario, respectively). In fact, the first most frequent answer is “demand to speak to the supervisor,” followed by “file a formal complaint” (see Figure 1), regardless of the scenario. However, we observe that the severity of the problem does make a difference for a person’s willingness to file a formal complaint: in our survey, proclivity to claim among respondents is higher in the scenario of police brutality compared to the scenario of discrimination at a public hospital (33.7% vs. 24.5%, as shown in Table 2 above).

Figure 1. Percentages of response categories in both scenarios.

Given these differences by scenario, in what follows, we model the proclivity to claim rights in each scenario separately and present our statistical findings accordingly and then discuss both the main factors that affect the outcome across models/scenarios and those that are particular to each.

Proclivity to claim when facing discrimination at a public hospital

In the first scenario that we presented to the survey participants, a public health staff discriminated against the respondent by denying them access to health care based on their personal characteristics. We begin the analysis estimating a logit model. Table 3 reports the results of two models, which vary in how socioeconomic status is categorized: Model 1 includes a categorical variable that distributes participants into three socioeconomic groups and Model 2 includes a variable that categorizes participants into five socioeconomic groups, as explained in the survey design section. The coefficients are interpreted in this way: if the odds ratios are greater than 1, it corresponds to positive effects of the given variable, while odds ratios between 0 and 1 correspond to negative effects of the given factor, decreasing the odds. Odds ratios equal to 1 imply no association between the factor and the dependent variable.

Table 3. Logistic models for scenario 1 – discrimination at a public hospital

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table 3 shows that, in the case of scenario 1, five factors are statistically related to the probability to turn to state authorities or institutions, regardless of how socioeconomic status is categorized. Two of these factors are related to people’s understandings and expectations in the scenario: first, respondents’ perceived knowledge of where to turn (i.e., declaring having some idea or knowing very well) increases the likelihood of proclivity to file a formal claim, a relationship in the positive direction. Second, respondents’ expectations about how just the outcome of claiming would be (i.e., envisioning the outcome of such action as totally or somewhat just) decreases the likelihood of their saying they would turn to state institutions to claim. Along with those factors, we observe that two self-reported experiential variables are statistically related to the likelihood of proclivity to claim in this scenario. Having participated in protests around the constitutional process increases the probability of an intent to claim, while having participated in informative sessions around the same process decreases that likelihood. Finally, participants’ age also shapes the probability of the modeled outcome. Specifically, being 60 years and older decreases the likelihood of being willing to claim in the face of discriminatory denial of health care at a public facility.

It is worth noting that other sociodemographic variables, such as gender or self-identification with an indigenous group, do not have a significant estimated statistical relationship with the probability of willingness to demand remedy for discrimination at a public hospital. Nor does socioeconomic status have a significant statistical relationship with people’s willingness to make formal claims in this scenario, regardless of how the variable is categorized. Similarly, neither recognizing the scenario as a rights violation nor self-reported knowledge of their rights in the situation is related to the probability of claiming at any statistically significant level.Footnote 16 Previous experience with courts and with state institutions is also not statistically significant.

While the odds ratio tells us valuable information about the direction and the statistical magnitude of the relationship, its interpretation is not straightforward. In Figure 2, we thus show the predicted probabilities of the proclivity to claim in this scenario based on the statistically significant factors found in Table 3.Footnote 17 We observe that having participated in a protest associated with the constitutional making process has the largest estimated relationship with the probability of being willing to claim if facing scenario 1. Specifically, the probability increases from 0.23 to 0.36, holding all the other variables constant. The second largest estimated relationship with the probability of the outcome of interest corresponds to the self-assessed knowledge of where to turn if facing discrimination at a public hospital: the probability increases from 0.197 to 0.287 if someone moves from declaring they have no or little knowledge about where to turn to declaring they have some idea or know very well, holding all the other variables constant.Footnote 18

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities (and 95% confidence interval) of statistically significant variables in Model 1.

Proclivity to claim when facing police brutality

The second scenario escalated the nature and severity of the harm. We presented participants with the hypothetical situation that they or a family member has been arrested by the police and physically abused by them. Again, we begin the analysis modeling the proclivity to claim by a logistic regression. Table 4 reports our results. Overall, we find that, similar to the case of discrimination at a public hospital, self-assessed knowledge of where to turn as well as having attended a march or a protest in the context of the ongoing constitutional process have a statistically significant relationship with the probability of being inclined to claim against police brutality, both in the expected positive direction. It is worth noting that these two variables are the only statistically significant in the models, regardless of how socioeconomic status is measured. All the other covariates, whether related to demographic characteristics or to people’s understandings, expectations or experiences, are not statistically significant predictors of the probability of being willing to claim when facing police abuse. As we found in scenario 1, participants’ structural position is not statistically related to the probability of being willing to claim rights when facing police brutality.

Table 4. Logistic models for scenario 2 – physical abuse by the police

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Looking at the predicted probabilities (see Figure 3), we observe that moving from having little or no knowledge about where to turn to having some or knowing very well increases the likelihood of being inclined to claim from 0.274 to 0.395, while having participated in a protest about the constitutional process boosts such probability from 0.324 to 0.453, holding all the other variables constant.Footnote 19

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities (and 95% confidence interval) of statistically significant variables in Model 3.

In sum, our statistical analysis has three main empirical findings. First, socioeconomic status/structural position of the respondent has no relationship with the probability of the proclivity to claim, regardless of the legal problem. Second, respondents’ self-assessed knowledge of where to turn if facing such hypothetical rights violations is associated with our dependent variable. Third, respondents’ participation in protests around the ongoing constitution making process also has a statistical relationship with the probability of their proclivity to claim. We turn now to a discussion of the theoretical relevance of these findings.

Discussion

The first thing to note is that, even in this context of high political and social mobilization involving the protest of inequality, calls for respect for the dignity of excluded groups and demands that average citizens be taken into account, our data support the argument that the type of legal problem matters for the proclivity to claim, which is consistent with other works in the socio-legal literature (Hendley Reference Hendley2017; Kritzer Reference Kritzer, Cane and Kritzer2010; Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022). This is clear in the fact that more people declared they would make a formal claim in scenario 2, which represents a physical abuse by a public authority, than in scenario 1, and that there are some covariates whose effects differ between scenarios.

However, and in contrast to some findings in the literature, in this context of high social mobilization, structural variables (class, gender and indigeneity) were not statistically associated with the proclivity to claim (with the partial exception of a negative estimated correlation for respondents 60 years of age and older in the health-care discrimination scenario only). Perhaps most notably, socioeconomic status is not statistically related to the probability of being inclined to claim in this survey, no matter how we categorize the variable. Respondents of lower socioeconomic status, i.e., the vast majority of the population in Chile’s highly unequal society, are estimated to be as likely as their more affluent counterparts to say they would make a claim in both scenarios. This evidence lends validity to Sally Merry’s classic argument that even people lacking social power may consider themselves deserving of equal treatment and entitled to seek redress from the state (Merry Reference Merry1990) and reinforces the finding by Hilbink et al. (Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022) in a previous qualitative study in Chile and Colombia.

In regard to respondents’ understandings and expectations about claiming – that is, their internal and external efficacy – a robust finding is that, across scenarios, respondents’ self-perceived knowledge of where to turn (i.e., declaring having some idea or knowing very well) increases the likelihood of proclivity to file a formal claim. However, neither recognition of the scenario as a rights violation nor the respondent’s sense that they “know their rights” in the situation was correlated with proclivity to make a formal claim, even though 36.9% and 49.8% labeled each scenario as a rights violation, respectively, and 64.4% and 61.9% declared knowing their rights in each hypothetical case. Together, these findings suggest that rights consciousness or conceptual knowledge is not enough to incline people to claim. What does appear necessary is a person’s belief that they have the practical knowledge about where to turn to engage the system when they feel wronged (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006; Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022).

Interestingly, professed willingness to claim is not statistically tied to positive expectations about how just the outcome of claiming would be (i.e., envisioning the outcome of such action as totally or somewhat just). In the police brutality scenario, there is no statistical relationship between these variables, while in the health discrimination scenario, expectation of achieving a “totally just or mostly just” outcome decreases the odds of the proclivity to claim. This suggests that it is not an instrumental calculation (i.e., believing that making a claim will result in a just outcome and therefore be worth the effort) that drives people’s willingness to claim, a finding that is consistent with a number of works in the literature (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2023; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006; Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022; Merry Reference Merry1990).

While some studies have found that prior experience with justice institutions or with claim-making on the state can increase a determination to claim in the future (e.g., Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006; Lake et al. Reference Lake, Mukatha and Walker2016), neither of these variables increased the likelihood of the proclivity to claim in our survey’s two scenarios. Indeed, 36% of respondents reported having experience with courts and 25% reported having made some kind of claim on the state in the past, yet we found no statistical relationship between these variables and the odds of the proclivity to make a formal claim in either of our scenarios.

What we did find was that participation in marches and protests, that is, active experience in the ongoing political and social mobilization, had the largest estimated relationship with the probability of being inclined to claim in both scenarios. Otherwise put, our data showed collective action to demand justice on the street to be statistically related to a willingness to turn to institutions to seek remedies for individual injustices. While it is possible that this is because individuals who are willing to go to the streets to air grievances are also more inclined to demand remedies, read in light of the literature on the relationship between social mobilization and legal consciousness, our data suggest an alternative hypothesis to be investigated in future work. As McCann (Reference McCann1994) has shown in the case of social movement activists, we propose that participation in protests might also have an empowerment effect on those who take part. In the case of Chile, numerous analysts observed that the massive protests of the social uprising opened up new spaces for individuals to practice their citizenship, to reimagine their relationship to the state and to demand that institutions and authorities address injustice and inequality (Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara Reference Ansaldi and Pardo-Vergara2020; Sajuria and Saffirio-Palma Reference Sajuria, Saffirio-Palma and Fuentes2023). The correlation that we found between participation in protests and willingness to turn to the state to demand remedies could thus reflect a process of social empowerment, akin to that which others have found, on a smaller scale, to be related to individual/micro-level interventions (e.g., Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006: 807) or social experiences (Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2023), that rendered individuals determined to turn to the state to make claims, even in (or particularly in) a context of disenchantment with the state.

It bears noting, however, that participation in town meetings and/or information sessions around the constitutional process had no positive estimated relationship with the proclivity to make claims in the face of the hypothetical rights violations. In fact, in scenario 1, participation in such meetings was statistically related in the opposite direction, decreasing the odds of being inclined to claim in response to the violation. This finding calls for more research across disciplines on the different effects that distinct types of political participation (e.g., protest vs. meetings) could have on people’s proclivity to claim when facing a justiciable problem in particular and on the exercise of citizen agency in general.

Conclusion: contributions, limitations and avenues for future research

In contemporary democracies, especially those characterized by high levels of social inequality, the rights people enjoy are far from universal and automatic; rather, they must be actively claimed. But under what conditions will people be willing to seek remedy when facing a rights violation? While some socio-legal scholars have found structural position and/or the cultural or ideological macro-context to be most important in shaping individuals’ legal consciousness, often inhibiting their pursuit of remedies in the face of rights violations (Gloppen Reference Gloppen, Gargarella, Domingo and Roux2006; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2000; Reference Nielsen2004), others contend that social experiences and political interventions, including participation in social movements, affect people’s willingness and determination to demand redress in the face of rights violations (McCann Reference McCann1994; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006; Reference Gallagher2023). Our study offers empirical and theoretical contributions to these debates and opens new avenues for research at the intersection of socio-legal studies and political participation.

To begin, we contribute data from a nationally representative survey collected amidst a mass mobilization that challenged the normative and institutional framework of state-society relations in a country which, like many in the world, pairs a democratic political system with high levels of social inequality. The timing of our survey allowed us to explore possible links at the individual level between participation in this collective mobilization and people’s proclivity to turn to the state to pursue remedies when facing rights violations, as well as to test, in this context of heightened political engagement, whether other variables identified in the socio-legal literature were correlated with willingness to claim.

Our analysis uncovered two statistical relationships of theoretical interest. First, we found empirical support, on a national scale in Chile, for the argument made in other times and places that an individual’s self-perceived knowledge of where to turn when facing a rights violation makes a crucial difference for their willingness to make claims on the state (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Buck, Patel, Denvir and Pleasence2010; Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Restrepo Sanín2022; MacDonald and Wei Reference MacDonald and Wei2016; Pleasance and Balmer Reference Pleasance and Balmer2014). As Kruks-Wisner (Reference Kruks-Wisner2018: 40–41) notes, formal information “is not enough” to increase citizen mobilization; rather, “citizens require tacit … knowledge of … where to go, whom to contact, and how best to communicate one’s needs and interests.” Notably, our survey results show that an individual’s self-reported possession of such tacit knowledge, reflecting personal confidence that they can navigate and work the system when experiencing a harm (i.e., internal efficacy), is not an automatic or exclusive product of wealth, education, and race and/or gender privilege. Beyond its theoretical implications, this finding furthers the idea that the cultivation of such internal efficacy through programs that aim at legal empowerment should be a central focus of access to justice policies (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006; Hernandez Reference Hernandez2010; Lake et al. Reference Lake, Mukatha and Walker2016; Tait Reference Tait2021).

Second, our study revealed a positive relationship between participation in protests and willingness to turn to the state to demand remedy but no link between participation in citizen meetings and such an inclination. Taking into consideration the findings of previous qualitative and mixed methods studies that demonstrate the ways that certain social and political experiences contribute to citizens’ sense of empowerment (e.g., McCann Reference McCann1994; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006; Reference Gallagher2023) but recognizing that we cannot draw causal inferences from a single, cross-sectional survey, we highlight this finding as generative of a specific hypothesis linking participation in large-scale protests to an enhanced sense of legal agency at the individual level. At a minimum, our results suggest that mobilization on the streets and through institutions is not an either/or proposition for people (Aytaç and Stokes Reference Aytaç and Stokes2019; Booysen Reference Booysen2007; Taylor Reference Taylor2020). However, more research is needed in order to determine whether this finding reflects characteristics of the actors that are independent of the context (i.e., personal disposition), or whether a specific experience of participating in protests has an empowering effect on the individuals, fueling a belief that change is possible, generally, and that they are entitled to and capable of making claims on the state in particular instances (Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018: 37–41). Such research could take the form of qualitative studies and/or quantitative longitudinal analyses in which the researchers can compare “before and after” observations with the same individuals (e.g., through panel surveys). This would allow researchers to ask important questions such as if and how respondents had participated in protests before, as well as to document in people’s own words their experiences in such instances of social mobilization and the self-perceived impact on their sense of entitlement and political efficacy.

In addition, our findings suggest that a fruitful avenue for future socio-legal research would be to explore if and how different forms of active claim-making, such as protesting around rights and justice, affect both people’s understandings of their available options as well as their actual behavior in response to rights violations. For example, scholars could expand the scope of the inquiry to explore whether the statistical relationships that we found among those who have not experienced particular hypothetical rights violations hold for individuals who have experienced them (or others) and, within that set, compare those who took different courses of action (demanding formal remedy or not).

Finally, while our data speak to a context that was particular to Chile in 2021, our study also has relevance for scholars who study other unequal democracies, from Peru to South Africa to the United States, where similar episodes of large-scale protests demanding social justice have recently taken place (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace). As Gamson (Reference Gamson1968: 48) argues, historical moments characterized by “a combination of high sense of political efficacy and low political trust is the optimum combination for mobilization–a belief that influence is both possible and necessary.” More comparative research is needed on the potential spillover effects of different experiences of political engagement on citizens’ perceptions of and responses to rights violations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/lsr.2024.11.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Bianet Castellanos, Christina Ewig, Jeffrey Davis, Jessica López-Lyman, María Sánchez, three anonymous reviewers and the LSR editors for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Financial support

This research was made possible by funding from a College of Liberal Arts Seed Grant for Social Science Research and a Human Rights Initiative Grant from the University of Minnesota (IRB STUDY00012629).