The fusuline genera Thailandina Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968 and Neothailandina Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968 were established by Toriyama and Kanmera (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968) based on material from the Khao Phlong Phrab section of the Permian Rat Buri Limestone in central Thailand that is currently assigned to the Khao Khad Formation of the Saraburi Group (Ueno and Charoentitirat, Reference Ueno, Charoentitirat, Ridd, Barber and Crow2011). These fusuline genera are peculiar in having parachomata and replaced tests by secondary mineralization. Moreover, Neothailandina was described to have a test with transverse septula, considered to be characteristic for Neoschwagerinidae. Based on these remarkable test features, Toriyama and Kanmera (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968) newly introduced the subfamily Thailandininae to accommodate these two new genera and assigned it to the Neoschwagerinidae, despite the lack of septula in Thailandina. Later, Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) argued that Thailandina and Neothailandina are just a mixed grouping of several known genera of schwagerinids, verbeekinids, and neoschwagerinids that are too altered by recrystallization to be recognizable, and rejected the taxonomic validity of these two genera as well as Thailandininae.

The Khao Phlong Phrab section represents one of the standard late Cisuralian−Guadalupian (late early−middle Permian) fusuline successions in the eastern Paleotethys (Zhang and Wang, Reference Zhang and Wang2018) and contains not only Thailandina and Neothailandina but also abundant schwagerinid, verbeekinid, and neoschwagerinid fusulines (Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975; Fig. 1). I investigated the original specimens described by Toriyama and Kanmera (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968) and Toriyama (Reference Toriyama1975) from the section that are housed in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences of Kyushu University, Japan. I found that most of the grounds for Kobayashi et al.'s (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) arguments to regard the thailandinin genera as taxonomically invalid are not supported by observations on these specimens as explained in the account that follows. In this taxonomic note, I propose that Thailandina and Neothailandina, and their family Thailandinidae, should be retained as valid taxonomic groups.

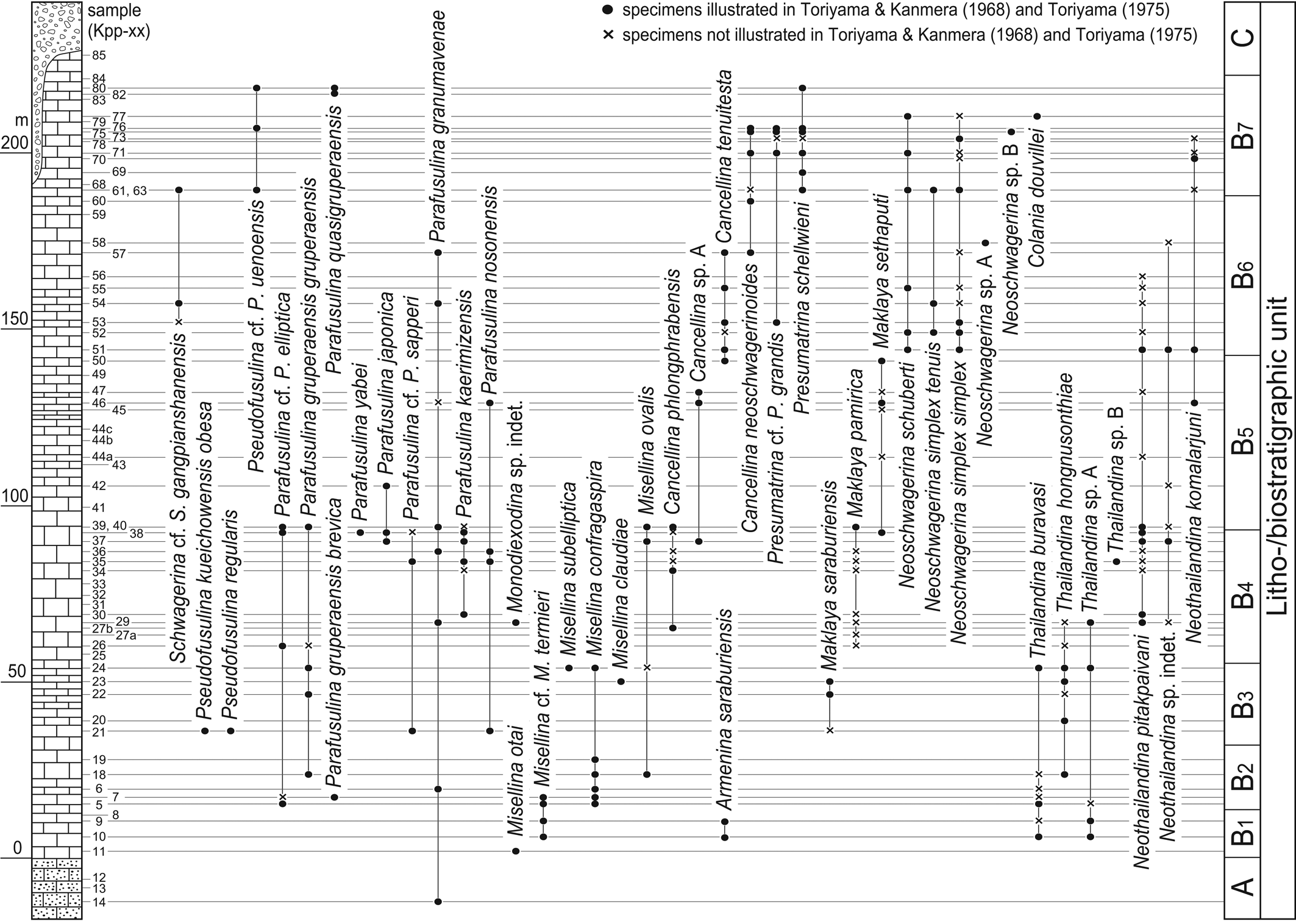

Figure 1. Stratigraphic ranges of Thailandina, Neothailandina, and associated major fusulines (schwagerinids, verbeekinids, and neoschwagerinids) in the Khao Phlong Phrab section of central Thailand (modified from Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975). Litho-/bioiostratigraphic units, A: mostly crystalline limestone, B1–B7: limestone, B1: Misellina otai-Misellina cf. Misselina termieri Biozone, B2: Misellina confragaspira Biozone, B3: Maklaya saraburiensis Biozone, B4: Maklaya pamirica Biozone, B5: Maklaya sethaputi Biozone, B6: Neoschwagerina simplex Biozone, B7: Presumatrina schellwieni Biozone, C: limestone conglomerate. Taxa include: Armenina saraburiensis (Toriyama and Kanmera in Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975); Cancellina neoschwagerinoides (Deprat, Reference Deprat1913); Cancellina phlongphrabensis Toriyama and Kanmera in Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975; Cancellina tenuitesta Kanmera, Reference Kanmera1963; Colania douvillei (Ozawa, Reference Ozawa1922); Maklaya pamirica (Leven, Reference Leven1967); Maklaya saraburiensis Kanmera and Toriyama, Reference Kanmera, Toriyama, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968; Maklaya sethaputi Kanmera and Toriyama, Reference Kanmera, Toriyama, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968; Misellina claudiae (Deprat, Reference Deprat1912); Misellina confragaspira Leven, Reference Leven1967; Misellina ovalis (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915); Misellina otai Sakaguchi and Sugano, Reference Sakaguchi and Sugano1966; Misellina subelliptica (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915); Misellina cf. Misellina termieri (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915); Neoschwagerina schuberti Kochansky-Devidé, Reference Kochansky-Devidé1958; Neoschwagerina simplex simplex Ozawa, Reference Ozawa1927; Neoschwagerina simplex tenuis Toriyama and Kanmera in Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975; Neothailandina komalarjuni Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968; Neothailandina pitakpaivani Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968; Parafusulina cf. Parafusulina elliptica Sheng, Reference Sheng1963; Parafusulina granumavenae (Roemer, Reference Roemer1880); Parafusulina gruperaensis brevica Sheng, Reference Sheng1963; Parafusulina gruperaensis gruperaensis Thompson and Miller, Reference Thompson and Miller1944; Parafusulina japonica (Gümbel, Reference Gümbel1874); Parafusulina kaerimizensis (Ozawa, Reference Ozawa1925); Parafusulina nosonensis Thompson and Wheeler in Thompson, Wheeler, and Hazzard, Reference Thompson, Wheeler and Hazzard1946; Parafusulina quasigruperaensis Sheng, Reference Sheng1963; Parafusulina cf. Parafusulina sapperi (Staff, Reference Staff1912); Parafusulina yabei Hanzawa, Reference Hanzawa1942; Presumatrina cf. Presumatrina grandis Leven, Reference Leven1967; Presumatrina schellwieni (Deprat, Reference Deprat1913); Pseudofusulina kueichowensis obesa Sheng, Reference Sheng1963; Pseudofusulina regularis (Schellwien, Reference Schellwien1898); Pseudofusulina cf. Pseudofusulina uenoensis Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1957; Schwagerina cf. Schwagerina. gangpianshanensis Sheng, Reference Sheng1965; Thailandina buravasi Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968; Thailandina hongnusonthiae Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968.

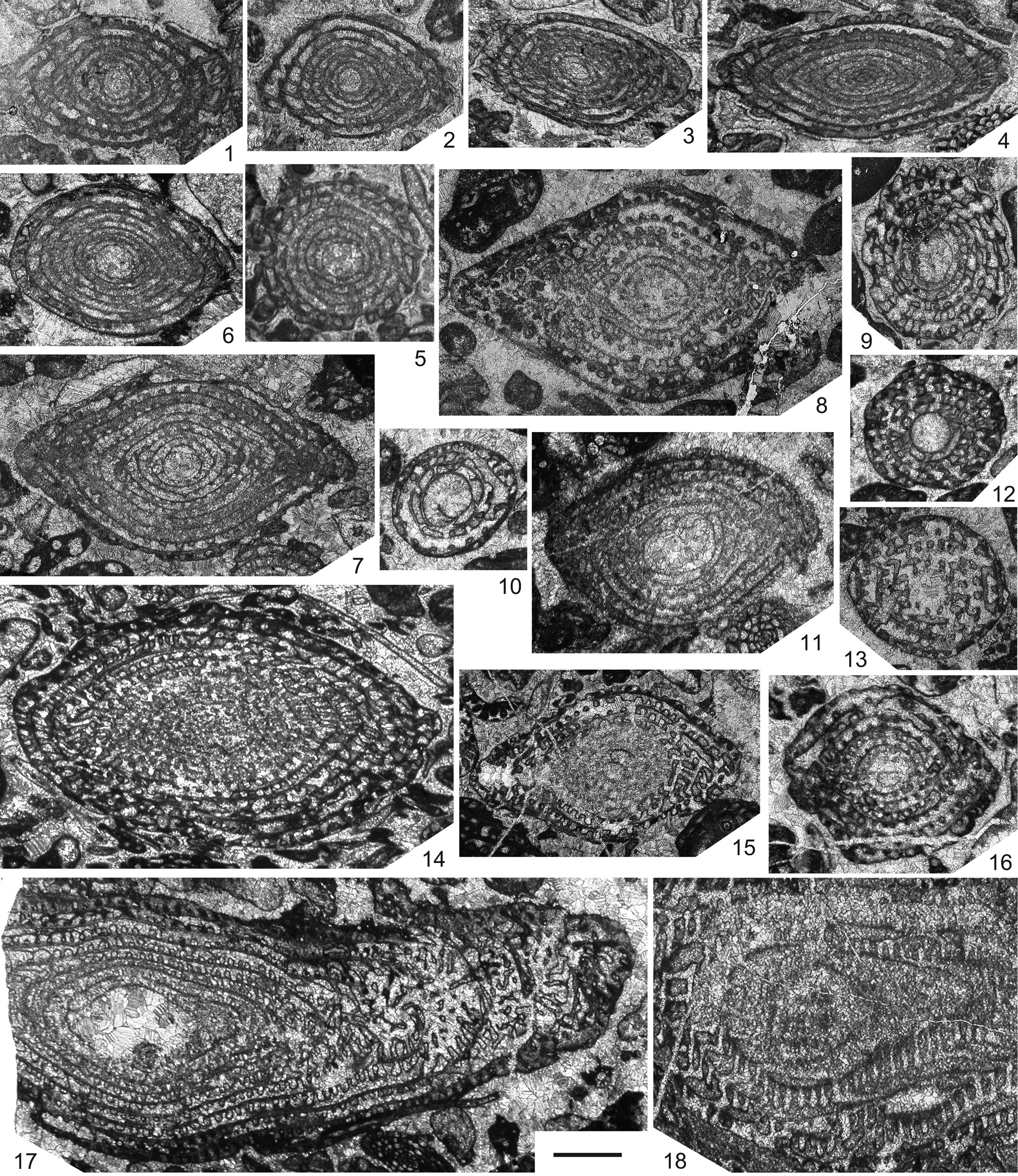

Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) noted, while referring to a similar opinion by Rauzer-Chernousova et al. (Reference Rauzer-Chernousova, Bensh, Vdovenko, Gibshman, Leven, Lipina, Reitlinger, Solov'eva and Chediya1996), that Thailandina buravasi Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968 (Figs. 2.1–2.5, 3.13), the type species of the genus, merely represents replaced specimens of the genus Misellina Schenck and Thompson, Reference Schenck and Thompson1940. In fact, Thailandina usually occurs together with several different species of Misellina (Figs. 1, 3.1–3.3, 3.9, 3.13), e.g., Misellina cf. Misellina termieri (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915) and Misellina confragaspira Leven, Reference Leven1967, and also occurs with the somewhat similar Armenina saraburiensis (Toriyama and Kanmera in Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975) (Fig. 3.8) and Maklaya saraburiensis Kanmera and Toriyama, Reference Kanmera, Toriyama, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968 (Fig. 3.4). But, T. buravasi consistently has an ~1.5−2 times larger test in axial length than coexisting Misellina, Armenina, and Maklaya spp. Thailandina hongnusonthiae Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968 (Fig. 2.7) and T. sp. A (Fig. 2.6) have even larger tests, which are definitely out of the size range of known Misellina spp. These observations conclude that Thailandina cannot be regarded as recrystallized specimens of coexisting Misellina, or even of the similar Armenina Miklukho-Maklay, Reference Miklukho-Maklay1955 and Maklaya Kanmera and Toriyama, Reference Kanmera, Toriyama, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968. Moreover, Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) thought that the apparent large to giant proloculi in thailandinin specimens are the mere result of recrystallization of (smaller) proloculi and the early few volutions of the test and thus, do not show the original size of the proloculus. However, this observation does not seem reasonable. As illustrated in Figures 2.1–2.3, 2.5–2.7, and 3.13, a circular wall seen in the central part of Thailandina makes a distinct boundary with the inner hollow space, which is filled with mosaic calcite crystals that are similar to sparry calcite cement surrounding fusuline tests in the same limestone sample. Additionally, there is no vestige of test structure inside the circular wall. These observations lead to an interpretation that the large spherical ‘openings’ in the central part of Thailandina tests could never be a replaced relict of small proloculi plus a few inner whorls, but indeed represent the proloculus. Neothailandina has even larger proloculi (Fig. 2.8–2.12, 2.16, 2.17) and, as in Thailandina, these specimens also have a sharp prolocular wall separating the inner hollow space and outer coiled chambers, although in some specimens (Fig. 2.8, 2.17), the wall becomes slightly vague. It is interesting to note that there is a somewhat irregular, large, first coiled chamber that surrounds the large proloculus in some Neothailandina specimens (Fig. 2.9, 2.11) and this resembles the circumproloculus chamber described by Thompson (Reference Thompson, Loeblich and Tappan1964, fig. 283). Thus, the large central ‘openings’ in both Thailandina and Neothailandina are not made by the selective recrystallization of the inner part of the tests, but are considered as innate morphology of these fusulines, i.e., the proloculus.

Figure 2. Thailandina and Neothailandina reported by Toriyama and Kanmera (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968) from the Khao Phlong Phrab section of central Thailand. Original photomicrographs from Toriyama and Kanmera's (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968) thin sections; plate and figure numbers in parentheses denote those by Toriyama and Kanmera (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968). (1–5): Thailandina buravasi Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968: (1) axial section of holotype (GK.D14009; pl. 6, fig. 1), Kpp-5; (2, 3) axial sections (pl. 6, figs. 5, 7), Kpp-5 and Kpp-24; (4) axial section of microspheric specimen (pl. 6, fig. 8), Kpp-5; (5) sagittal section (pl. 6, fig. 13), Kpp-5; (6) Thailandina sp. A, axial section (pl. 6, fig. 16), Kpp-10; (7) Thailandina hongnusonthiae Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968: axial section of holotype (GK.D13712a; pl. 7, fig. 1), Kpp-20; (8–16) Neothailandina pitakpaivani Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968: (8) axial section of holotype (GK.D13074a; pl. 7, fig. 9), Kpp-39; (9, 10, 12) sagittal sections (pl. 8, figs. 4, 5, 7), Kpp-30 and Kpp-39; (11, 15, 16) axial sections (pl. 7, figs. 10, 12, 14), Kpp-29, Kpp-37, and Kpp-51; (13) tangential section (pl. 7, fig. 19), Kpp-39; (14) oblique section (pl. 7, fig. 17), Kpp-29; (17, 18): Neothailandina komalarjuni Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968: (17) axial section (pl. 8, fig. 12), Kpp-51; (18) tangential section (pl. 8, fig. 14), Kpp-46. Scale bar = 1 mm (applicable to all specimens).

Figure 3. Major schwagerinid, verbeekinid, and neoschwagerinid fusulines associated with Thailandina and Neothailandina from the Khao Phlong Phrab section of central Thailand, as reported by Toriyama (Reference Toriyama1975). Original photomicrographs from Toriyama's (Reference Toriyama1975) thin sections; plate and figure numbers in parentheses in (1−12) denote those by Toriyama (Reference Toriyama1975). (1) Misellina cf. Misellina termieri (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915), axial section (pl. 12, fig. 7), Kpp-9; (2) Misellina confragaspira Leven, Reference Leven1967, axial section (pl. 12, fig. 11), Kpp-5; (3) Misellina claudiae (Deprat, Reference Deprat1912), axial section (pl. 13, fig. 1), Kpp-23; (4) Maklaya saraburiensis Kanmera and Toriyama, Reference Kanmera, Toriyama, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968, axial section (pl. 18, fig. 21), Kpp-22; (5) Maklaya pamirica (Leven, Reference Leven1967), axial section (pl. 18, fig. 16), Kpp-39; (6) Neoschwagerina simplex simplex Ozawa, Reference Ozawa1927, axial section (pl. 19, fig. 26), Kpp-52; (7) Colania douvillei (Ozawa, Reference Ozawa1922), axial section (pl. 20, fig. 23), Kpp-77; (8) Armenina saraburiensis (Toriyama and Kanmera in Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975), axial section (pl. 13, fig. 16), Kpp-9; (9) Misellina subelliptica (Deprat, Reference Deprat1915), axial section (pl. 12, fig. 3), Kpp-24; (10) Cancellina phlongphrabensis Toriyama and Kanmera in Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975, axial section (pl. 16, fig. 18), Kpp-34; (11) Pseudofusulina kueichowensis obesa Sheng, Reference Sheng1963, axial section (pl. 2, fig. 5), Kpp-21; (12) Parafusulina japonica (Gümbel, Reference Gümbel1874), axial section (pl. 5, fig. 4), Kpp-38; (13) Thailandina buravasi (left) and Misellina cf. Misellina termieri (right) showing two different modes of preservation in the same thin section, Kpp-5; this photomicrograph has almost the same field of view as that shown by Toriyama and Kanmera (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968, pl. 8, fig. 15)—note that the proloculus and the chambers of T. buravasi are filled with sparry calcite cement that has a similar nature to that seen in interstitial spaces between grains in this limestone. Scale bars = 1 mm.

As for some Neothailandina (Fig. 2.8, 2.10, 2.15–2.18), Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) considered that they are probably referable to recrystallized Parafusulina-like schwagerinids. In this regard, they probably mistook regularly arranged semicircular structures seen in the lower part of chambers in the outer volutions of Neothailandina for septal loops in schwagerinids. In fact, there are a number of schwagerinid species, including those of Parafusulina Dunbar and Skinner, Reference Dunbar and Skinner1931, co-occurring with Neothailandina in the Khao Phlong Phrab section (Fig. 1). However, most associated Parafusulina spp. have elongate fusiform and cylindrical tests exemplified by Parafusulina japonica (Gümbel, Reference Gümbel1874) (Fig. 3.12), and are fundamentally different in gross test morphology from thailandinids. Especially, Neothailandina komalarjuni Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968 (Fig. 2.17, 2.18), with its gigantic test, is not comparable to any schwagerinids from the section. There are a few species of Parafusulina and Pseudofusulina Dunbar and Skinner, Reference Dunbar and Skinner1931 that have fusiform or short cylindrical tests (e.g., Pseudofusulina kueichowensis obesa Sheng, Reference Sheng1963; Fig. 3.11). But, they have different internal test structures from thailandinids and so, these schwagerinids would not look like thailandinids even if they exhibited recrystallization. Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) also stated that some of Neothailandina (including the specimen illustrated in Fig. 2.14) are possibly recrystallized Neoschwagerinidae because vague, recrystallized partitions are preserved that probably correspond to transverse and axial septula. As shown in Fig. 1, there are a number of neoschwagerinid species from the Khao Phlong Phrab section and Toriyama (Reference Toriyama1975) illustrated somewhat large neoschwagerinid specimens, e.g., Neoschwagerina simplex simplex Ozawa, Reference Ozawa1927 (Fig. 3.6) and Colania douvillei (Ozawa, Reference Ozawa1922) (Fig. 3.7). However, the specimens of Neothailandina pitakpaivani Toriyama and Kanmera, Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968, which Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) considered to be replaced Neoschwagerinidae, occurred in samples Kpp-29 and Kpp-37 from the Maklaya pamirica Biozone (B4) (Fig. 1). In this interval, neoschwagerinids consist of Maklaya pamirica (Leven, Reference Leven1967) (Fig. 3.5), Cancellina phlongphrabensis Toriyama and Kanmera in Toriyama, Reference Toriyama1975 (Fig. 3.10), and Cancellina sp. A, and all of these species are much smaller than Neothailandina pitakpaivani. Thus, it is not likely that Neothailandina resulted from simple recrystallization of coexisting neoschwagerinids in the B4 biostratigraphic interval where the relevant Neothailandina pitakpaivani specimens were obtained.

The above-mentioned various lines of evidence lead to a conclusion that Thailandina and Neothailandina are not mere taphotaxa (Lucas, Reference Lucas2001) formed in the course of diagenesis, but are indeed existing taxonomic entities that can be characterized by recrystallized tests probably originally of aragonite (e.g., Fig. 3.13) and parachomata (e.g., Fig. 2.1, 2.16). Moreover, Neothailandina has partitions of the chambers, which correspond to transverse septula (Fig. 2.13, 2.15, 2.18). The supposed original aragonitic test mineralogy in Thailandinidae suggests a close phylogenetic relationship to the existing fusuline family Staffellidae (Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Pille and Gaillot2010), but the development of parachomata and transverse septula is disparate from that family. In view of the higher taxonomy of the fusulines, therefore, Thailandina and Neothailandina should be considered as forming a distinct family that constitutes a small collateral clade of Staffellidae in the superfamily Staffelloidea of the order Fusulinida.

In conclusion, contrary to Kobayashi et al.'s (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) arguments, Thailandina and Neothailandina, and the higher taxon Thailandinidae to include these genera, should be retained as taxonomically valid and included in the Staffelloidea in fusuline systematics. Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) assumed, while referring to a notable photomicrograph by Toriyama and Kanmera (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968, pl. 8, fig. 15) showing Thailandina with a recrystallized test in close association with well-preserved Misellina (Fig. 3.13), that it appears to be an exceptional example of (selective) metamorphic recrystallization. However, my thorough observation of Toriyama and Kanmera's (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968) and Toriyama's (Reference Toriyama1975) Khao Phlong Phrab material concludes that this case can be of universal application to all of the co-occurrences of thailandinids and other microgranular fusulines from the section. In those samples, all tests of Thailandinidae are invariably recrystallized whereas microgranular species are always well preserved. Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010) further argued that sedimentary reworking of specimens at a disconformity can also potentially produce a mixture of specimens in different preservation states. As noted above, however, the internal spaces (proloculus and chambers) of thailandinid tests are filled with the same type of cement found in the interstitial spaces between grains in the host limestone (Fig. 3.13). That interpretation is, therefore, rejected for the Khao Phlong Phrab thailandinids. Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Ross and Ross2010, fig. 1) illustrated schwagerinid, neoschwagerinid, and verbeekinid fusuline specimens from the Akasaka Limestone of central Japan that represent several different states of contact metamorphic alteration from partial recrystallization to complete degradation of tests. Using this example, they intended to demonstrate that thailandinids were made by a similar metamorphic process affected on other microgranular fusulines. But, those illustrated fusulines show an essentially different recrystallization appearance from thailandinid specimens in the Khao Phlong Phrab section (e.g., Fig. 3.13). Recrystallization of the latter is due probably to the mineralogical change from aragonite to calcite in their tests, which occurred during early diagenesis. It is a different content from contact metamorphism.

A similar occurrence in the mixture of recrystallized Thailandina and well-preserved microgranular fusulines (verbeekinids and neoschwagerinids) was also reported by Zhou and Liengjarern (Reference Zhou and Liengjarern2007) from the Nong Pong Formation of the Saraburi Group, located ~40 km east of Khao Phlong Phrab. In that area, Thailandina shows identical test features to those from the Khao Phlong Phrab section, representing a slightly recrystallized appearance, whereas associated verbeekinids and neoschwagerinids retain their original microgranular test walls. This occurrence gives additional supporting evidence that thailandinids are not mere accidental products made by local metamorphism on particular limestones containing Misellina, Parafusulina-like schwagerinids, and other neoschwagerinids, but they comprise a valid taxonomic group characterized by inherent aragonitic test mineralogy.

Acknowledgments

I thank H. Sano (Kyushu University, Japan) for providing access to Toriyama and Kanmera's (Reference Toriyama, Kanmera, Kobayashi and Toriyama1968) and Toriyama's (Reference Toriyama1975) thin sections housed in Kyushu University's Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences (GK.D). I am also grateful to M.K. Nestell (University of Texas at Arlington, USA) and Y. Wang (Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for their constructive reviews, and to J.S. Jin and G. Nestell for editorial suggestions.