For C.

Mahler’s Third Symphony is a work of complex structure and intricate hermeneutical layers. Within this massive construction, the first movement is particularly intriguing: although it comes first in the final layout of the symphony, it was the last to be composed. Its building blocks and thematic labyrinths continue to fascinate scholars, provoking further attempts at interpretation. This article describes a new source that helps us to expand our knowledge about the genesis of this movement and about the evolution of its thematic content. It offers a description of the features and content of the source, relying on the reinterpretation of known letters, testimonies and scholarly work in order to determine its place among the known Mahler manuscripts and in the chronology of the genesis of the symphony.

The central section of the article establishes a direct connection between the new manuscript and one housed at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna.Footnote 1 With not a single bar missing between the end of the former and the beginning of the latter, there is no doubt whatsoever that these two not only belong together, but are to be regarded as a single unit occupying six pages altogether, containing all the thematic blocks of the material found in the opening part of the movement. This connection permits us to remove some uncertainties regarding the early phases of what Mahler called the introduction to the first movement, before he combined it with the rest of the score.Footnote 2 It is impossible to know all the details of how events unfolded, but the discovery of the source presented here does clear up at least one crucial part of the picture, bringing us a step closer to understanding the structural process behind Mahler’s symphonic masterpiece.

1 Contextual and chronological setting and known manuscript sources for the first movement

Most of the chronology of the composition of the Third Symphony has already been relatively well documented. It is widely accepted that the first known sketches for this symphonic work date back to Mahler’s first summer in Steinbach am Attersee in 1893. Mahler was then an established conductor in Hamburg, and the summer was dedicated to his work on the Second Symphony. The Third Symphony began to see the light of day two years later, when the composer drafted all the movements known today except the first. He also jotted down some ideas for the introductory movement, but the bulk of the work on what would later become that stunning half-hour of music took place in the summer of 1896. It did not go smoothly, however, as Mahler had left the sketches he needed at home in Hamburg and was waiting restlessly for them to arrive. Once he received them, the work developed fairly quickly, and Mahler could soon congratulate himself on a finished draft score of the symphony.

The most interesting part of the genesis of the manuscript source under scrutiny occurred during the week of 12–19 June 1896. This is the time Mahler spent in Steinbach waiting for the sketches he had left behind. We know that he arrived at his new summer residence on 11 June, because on the following day he posted a letter he had written in panic to his friend Hermann Behn, who happened to be on vacation not too far from Hamburg, asking him to go to his home, collect the forgotten sketches and send them to Steinbach as soon as possible.Footnote 3 Behn did as asked, but the sketches did not arrive immediately and Mahler filled the days with working on unplanned things. If we are to rely on Natalie Bauer-Lechner’s testimony, she joined Mahler and his sisters on 14 June and witnessed the rest of the compositional process as it unfolded.Footnote 4 According to her, Mahler composed the lied Lob des hohen Verstandes during that time, as well as something else:

He also drafted the introduction to the first movement of the Third. Of this, he said: ‘It has almost ceased to be music; it is hardly anything but sounds of Nature. It’s eerie, the way life gradually breaks through, out of soulless, petrified matter. (I might equally well have called the movement “Was mir das Felsgebirge erzählt” [“What the mountains tell me”]). And, as this life rises from stage to stage, it takes on ever more highly developed forms: flowers, beasts, man, up to the sphere of the spirits, the “angels”. Once again, an atmosphere of brooding summer midday heat hangs over the introduction to this movement; not a breath stirs, all life is suspended, and the sun-drenched air trembles and vibrates […] At intervals there come the moans of the youth, of captive life struggling for release from the clutches of lifeless, rigid Nature. In the first movement, which follows the introduction, attacca, he finally breaks through and triumphs.’Footnote 5

The piano that Mahler needed for his work was also delayed, but it eventually arrived,Footnote 6 preceding the sketches, which finally reached Steinbach on 19 June.Footnote 7 By then he had the planned ‘introduction’ to the first movement written down, and the content of the newly arrived sketches allowed him to work on the rest, which he did, completing the draft on 28 June.Footnote 8 The orchestration was finished by the end of July.Footnote 9

For a symphonic movement of such elaborate structure and length, the number of existing sources for the various stages of composition is limited. The list of known sources, excluding the latest document discussed here, is (in apparently chronological order):

(1) Stanford 630: a single bifolio of 18-stave paper, containing early fragmentary sketches for what would later become the central march in the first movement of the Third Symphony, as well as material from the second movement of the Second Symphony; most probably dating from 1893.Footnote 10

(2) Stanford 631: four separate leaves of 24-stave paper, seven sides notated, the last one blank; containing sketches for parts of the first three movements of the Third Symphony; manuscript dated (not in Mahler’s handwriting) 1895.Footnote 11

(3) ÖNB 22794: a single bifolio of 24-stave paper, three sides notated, the last one blank; material for part of the opening section of the first movement; suggested dating June 1896.Footnote 12

(4) Albrecht 1147 B: fair copy of all six movements, 110 pages, 106 notated; October 1896.Footnote 13

Neither the completed full draft score of the movement nor any part of it has come to light. Apart from the manuscripts listed above, there are a few other sources that are more or less directly related to the genesis of the first movement and in particular to the document that is the subject of this study. These sources concern the fourth movement, the setting of Nietzsche’s text ‘O Mensch! Gib Acht!’ from Also sprach Zarathustra. Apart from the fair copy (Albrecht 1147 B), the known documents containing material for this part of the symphony are:

(1) Cary 283 (Albrecht 1147 C): draft full score of movements 3–5 on 24-stave paper, 4 folios, 16 pages; 1895.Footnote 14

(2) Library of Congress manuscript: piano draft of the fourth movement, 1 bifolio; summer 1896.Footnote 15

Their general importance for the symphony aside, these two manuscripts are relevant for our understanding of the connection between the fourth-movement material and the beginning of the first movement because at the time of composition of the opening of the symphony the fourth movement had not yet taken its final form.

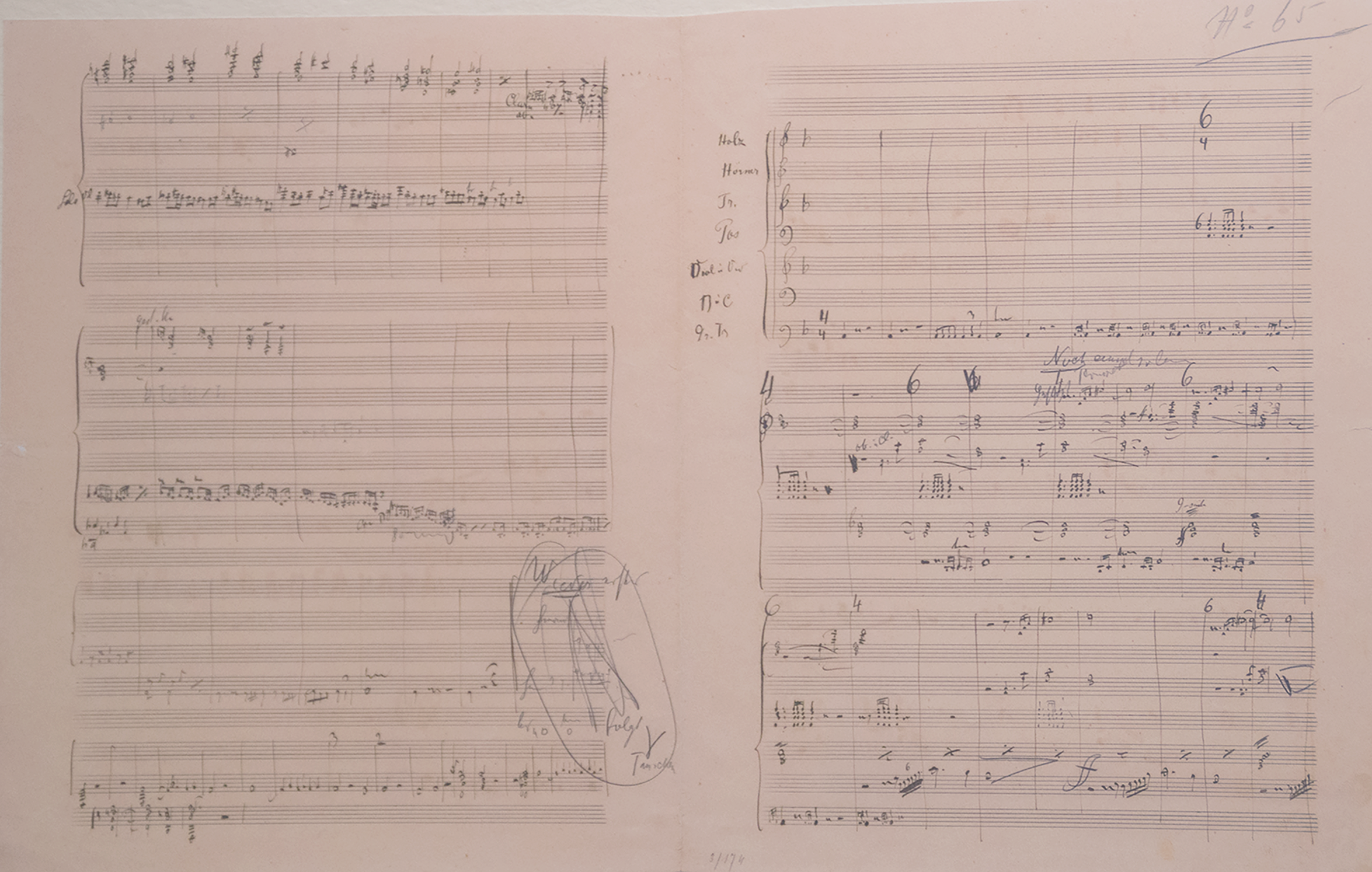

2.1 Description of the manuscript Steinbach 1896 Footnote 16

The manuscript which is the focus of this article – Steinbach 1896 (see Figures 1–2) – was sold at auction, probably in Austria, at the price of 250 schillings or Reichsmarks, perhaps to a family member of the present owner or to somebody who eventually gave or sold it to the family. The accompanying documents contain the following description, cut from the auction catalogue:

174 Mahler, Gustav, Komponist u. Dirigent. 1860–1911. Eigenhändiges Musikmanuskript. 4 Quart[o]-Seiten a. d. ersten Niederschrift der III. Symphonie, Tinte, mit Ergänzungen, Korrekturen und Anmerkungen mit Bleistift. Beigelegt eine Visitkarte der Witwe des Komponisten mit einigen erklärenden Worten. 250 –

Sehr schönes und interessantes Autograph.Footnote 17

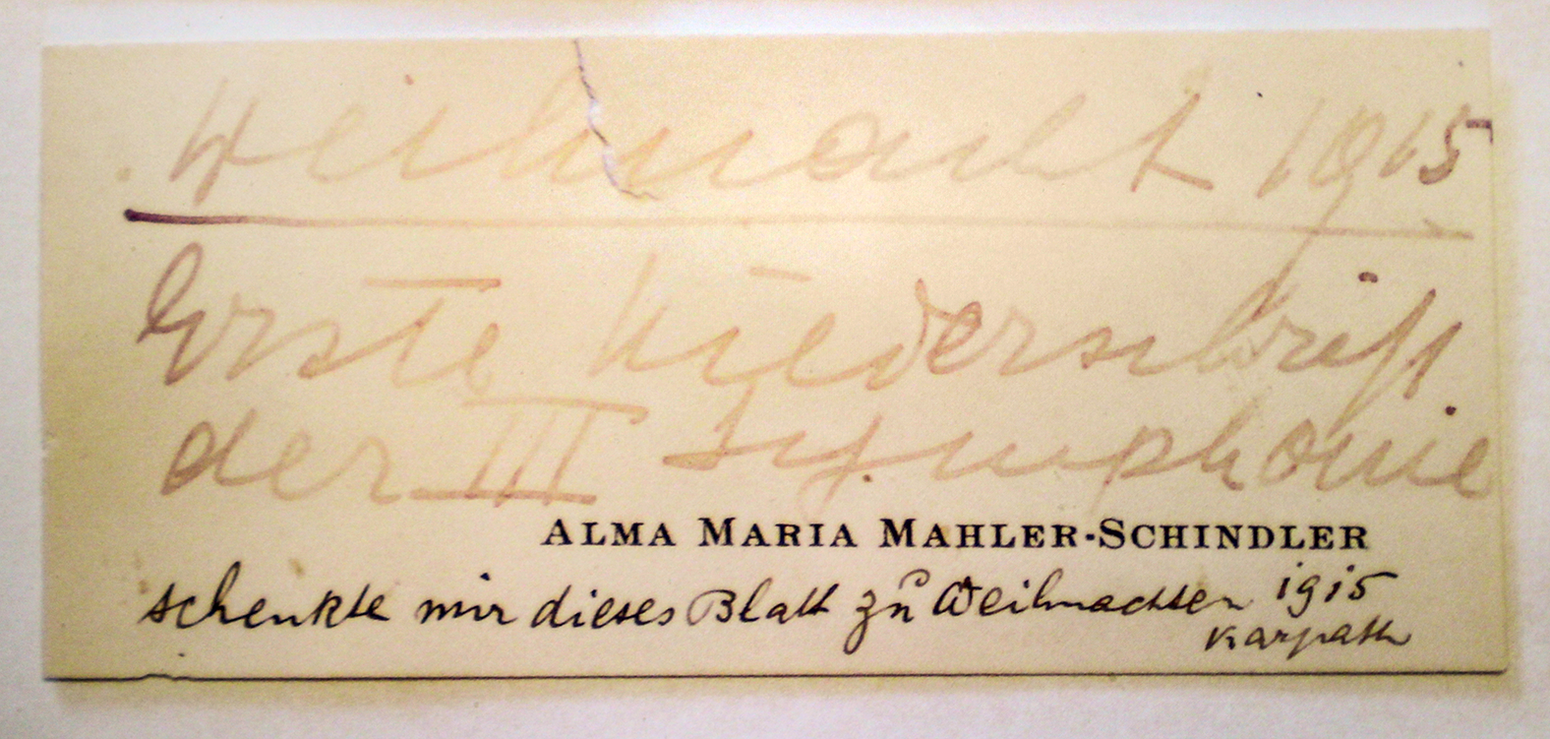

The number 174 is presumably the auction lot number. The visiting card (Visitkarte) mentioned in the description is preserved with the manuscript and has Alma Mahler’s handwriting on both sides (see Figures 3–4). The slightly faded recto reads ‘Alma Maria Mahler-Schindler’ in print, and above (in Alma’s hand and in the lavender ink she generally used) are the following words:

Weihnacht 1915 / Erste Niederschrift / der III SymphonieFootnote 18

Figure 1 Steinbach 1896, recto of bifolio, sides a (right) and d.

Figure 2 Steinbach 1896, verso of bifolio, sides b and c.

Figure 3 Recto of Alma Mahler’s visiting card that accompanied Steinbach 1896, with a handwritten addition by Ludwig Karpath.

Figure 4 Verso of Alma Mahler’s visiting card with her handwritten dedication to Karpath.

The original recipient of the manuscript is revealed in another hand and in black ink, under Alma Mahler’s printed name:

[Alma] schenkte mir dieses Blatt zu Weihnachten 1915 / KarpathFootnote 19

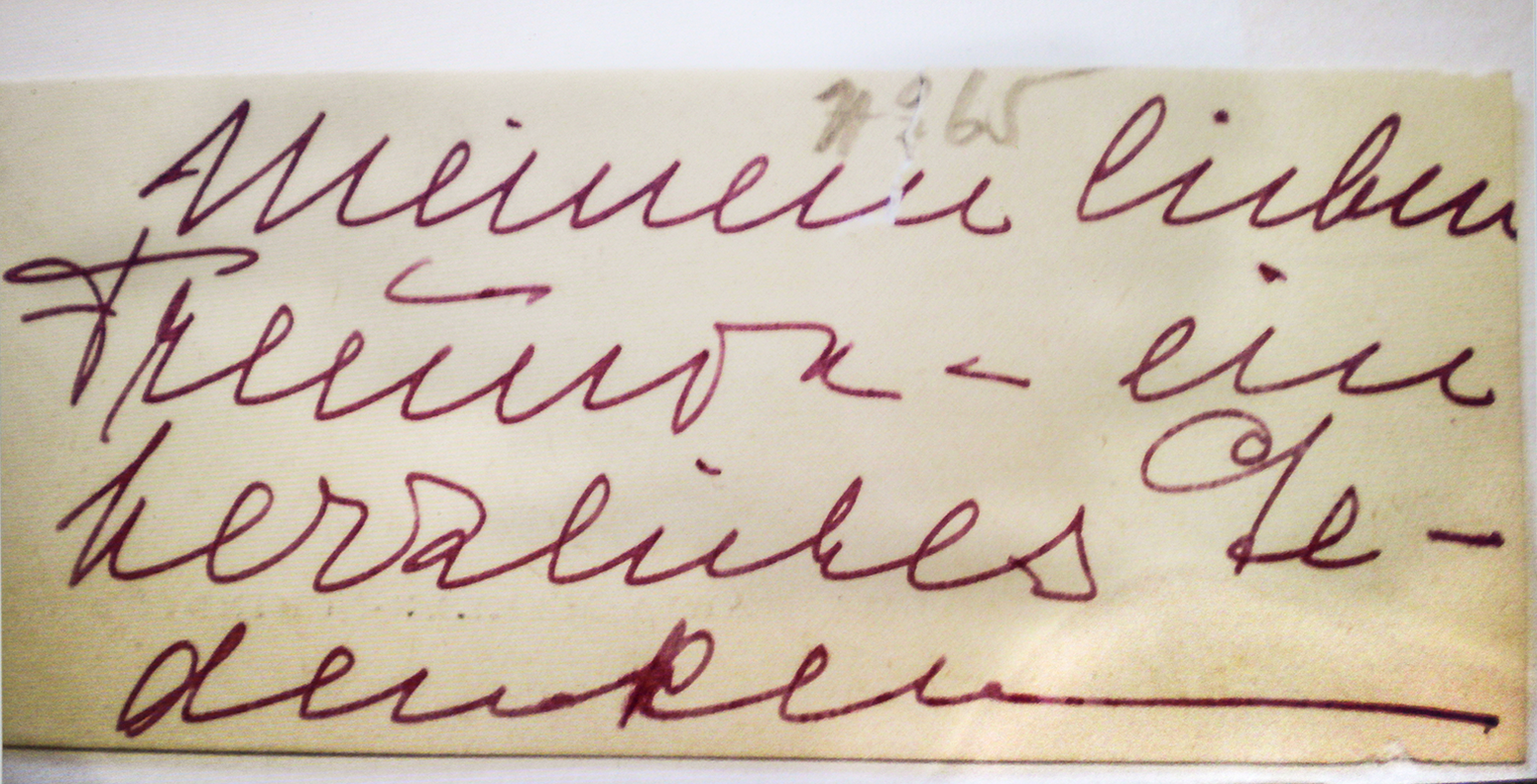

‘Karpath’ refers in all probability to Ludwig Karpath,Footnote 20 with whom Mahler became acquainted prior to becoming director of the Vienna Hofoper. Although in later years the acquaintance cooled slightly, Karpath never fully disappeared from Mahler’s circle and got closer to Mahler’s widow after the composer’s death, as this document suggests. The verso of the card contains only the following words in Alma’s handwriting:

Meinem lieben / Freunden – ein / herzliches Ge- / denkenFootnote 21

A logical conclusion seems to be that Alma Mahler gave the manuscript to Karpath as a Christmas present in 1915. Precisely what happened to it thereafter is currently unknown and difficult to determine. Considering the sentimental value of the gift, it is unlikely, though not impossible, that the document was sold before Karpath’s death in 1936. Karpath’s last will and testament contains specific instructions that all signed photographs given to him by famous people, along with autograph manuscripts found in his bequest, be sold after his death.Footnote 22 The manuscript has the inscription ‘n° 65’ in pencil in the upper right corner of the first page, as does Alma Mahler’s visiting card on the verso side, above the word ‘meinem’. Since it appears on both items and does not correspond to the auction number, it is possible that it was added either by the person who catalogued Karpath’s papers or by a subsequent owner. In addition, the first page of the manuscript has the inscription ‘3 / 174’ in the lower left corner in pencil. The number 174 could be the auction number, with ‘3’ listing the number of the document within the lot, though the catalogue text quoted earlier does not list items other than the manuscript and the visiting card, and ‘174’ therefore might refer to something else entirely. Everything else in the document was written by Mahler.

The manuscript is in fairly good condition. It is a single upright bifolio without a cover, all four sides bearing notated content and Mahler’s remarks. The paper matches that used by Mahler at the time: it has 24 staves, and was trimmed by hand with overall dimensions varying by only a few millimetres. Table 1 shows its dimensions, as well as those of the related manuscript ÖNB 22794. There is no visible watermark in the paper. Mahler normally used black ink for the first round of writing and pencil for later entries and annotations, although the use of ink for later amendments was not too unusual. The sketch contains material for the first movement of the symphony, as well as a line with a few bars from the fourth. The first-movement material is written on 11 seven-stave systems followed by a four-stave system, for a total of 113 bars; in the final version of the symphony these would be stretched over 143 bars (bars 21–163). The last three staves (a system of two staves plus a single stave) on the last page of the manuscript, consisting of 16 + 3 (with Mahler’s subsequent correction, 2) bars, could be rather important for the ascertainment of the chronology of the composition of the first movement. These three staves, of which the uppermost one is empty apart from two metrical indications (bar 8, 3[/2]; bar 9, 2[/2]), introduce a version of the material from the fourth movement, namely the opening bars before the song from Nietzsche’s Also sprach Zarathustra. It is significant that the staves in question are visibly separated from the rest.

Table 1 PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF STEINBACH 1896 AND ÖNB 22794

| Steinbach 1896 | ÖNB 22794 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total height (cm) | 31.6–31.8 | 31.6–32.0 |

| Total width (cm) | 49.0–49.8 | 50.1–50.5 |

| No. of staves | 24 | 24 |

| Total span (cm) | 27.6 | 27.5 |

| Stave height (cm) | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Vertical space between staves (cm) | 0.5 | 0.55–0.6 |

| Horizontal space between staves (cm) | 5.5 | 5.6 |

A more inquisitive look at the content of the manuscript reveals that the instrumentation is quite clearly indicated at the first system, on side a, as:

Holz

Hörner

Tr[ompete]

Pos[aune]

Viol[ine] u[nd] Vio[la]

B[äße] u[nd] C[elli]

Gr[oßer] Tr[ommel]

The tonality of D minor is indicated only on this system of the manuscript, on the first, third, fifth and seventh staves. This may mean that, regardless of the content’s position in the final concept, at that particular point of the compositional process the beginning sketched in this document might very well have been intended as the beginning of the symphony itself. A significant feature of this material is continuity, which brings us to the characteristics of the manuscript and its place in the chronology of Mahler’s creative process. It is not always easy to determine with precision to which category – draft, sketch, short score – a certain document belongs, because a single manuscript often manifests characteristics that allow it to be assigned to more than one category. Sketches, for instance, appear often at later stages in Mahler’s composition process, since he kept working and reworking certain fragments of his music, sometimes even after it had been printed – the Fifth Symphony being a notorious case.

One of the main features of Mahler’s short scores is the mostly consistent presence of four-stave systems. In the case of the present document, however, the seven-stave systems might indicate that this document is a short score; the content, however, suggests that it is closer to a sketch/draft short score. It shows that from the beginning Mahler had very clear ideas about instrumentation. This is obvious from the instrument indications on the first system as well as from later pencil entries. The ink entries show that Mahler had thought out the solo violin part from the start; it is virtually the same as in the completed score (see the last bar of the last system on side c and the first eight bars of the first system on side d of the manuscript: bars 140–7 in the completed score). He also includes specific timbral nuances, such as ‘Trompete gestopft’ written in pencil in the fifth bar of the second system of side a; ‘G-Saite’ in the violins two bars later; ‘offene’ in the trumpets in the second system of side b; and ‘gest[opft]’ in the horns and trombones in the first system of side c.

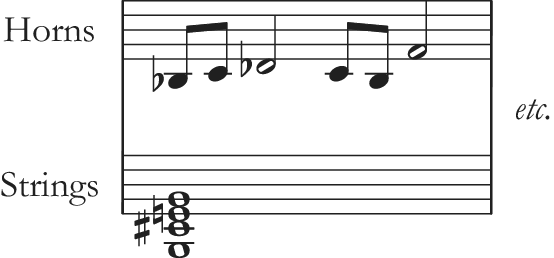

The metrical alternation between 6/4 and 4/4 found on sides a and b was reduced uniformly to 4/4 in the completed score. There is some vertical overlapping of the material that belongs to different bars in the complete score, as well as some absence of overlapping in relation to the final version. For instance, in the first system of side c, bars 5–7, the high strings stave contains the equivalent of bars 106–7 of the final version, whereas the horn stave displays the content of bars 100–3 (see Example 1).

Example 1 Steinbach 1896, side c, system 1, bar 5, staves 6 (above) and 5 (below). In the sketch, the horn part, here in the upper stave, was written below the strings. Mahler continued to write out the passage in the following bars but without paying attention to their metre.

Apart from the material in Steinbach 1896 that did find its way into the final score of the symphony, there is a certain amount that did not. Some chords are richer in the sketch than in the final score, and while some motifs appear more than once, others do not. The instrumentation, however, remains more or less the same. In the course of writing, Mahler would sometimes switch staves and instruments, so that trumpets might end up being on the second stave and horns on the third, for example. One could argue that Mahler first wrote the music and later decided to reassign it to a different instrument group, as he wrote ‘Trompete’ in pencil over the material originally assigned to the woodwind in the second system of side a. In the same system, Mahler wrote the pedal D minor chord in the horn stave, but by changing the clef to bass, he reassigned the content to the strings (it would eventually be played by violas). Then there are the pencil entries, most of them added after those in ink,Footnote 23 with which Mahler added instrumental indications or jotted down variations of the existing content – the first systems on both side b and side c are good examples. Among those pencil entries, the one at the end of the first-movement material is very important. Immediately after the last bar, corresponding to bar 163 in the completed score, Mahler wrote the following:

Wieder erstes [the first again]

Hinauf [up]

hinan [down]

Folgt [follows]

VPan schläft [Pan sleeps]

Mahler normally used the ‘V’ sign to indicate that something should be inserted at that point. In this case, it could only have referred to the ‘Pan schläft’ material. The whole entry, however, is crossed out, again in pencil, suggesting that Mahler changed his mind about it.

The very last system in the manuscript, right under the ‘Wieder erstes’ content and separated from the rest of the material, although written in ink, displays a variant of the beginning of the fourth movement. The place and the manner in which it is written (at the bottom of the page, separate from the rest) may indicate that Mahler perhaps wanted to connect it to the rest of the material in the sketch and therefore wrote it down on the same sheet of paper, planning to integrate it at a later point. However, it is equally possible that he simply used the free space on the sheet to jot down an idea that came to him at the time.

2.2 Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794

For a proper analysis and contextualization of Steinbach 1896 it is important to place it side by side with the related manuscript ÖNB 22794. Unlike the rest of the symphony (with the exception of some parts of the finale), the first movement had a wild structural metamorphosis. First conceived as an introduction to the rest of the symphony, the movement reached a point at which Mahler thought it required an introduction of its own. From the very beginning, when it was still merely a prelude in Mahler’s head, it was named ‘Der Sommer marschiert ein’, a title that would persist. For the sake of clarity, here is the evolution of titles for the first part of the symphony (in all its forms):

Summer 1895:

– Der Sommer marschiert ein.Footnote 24

(Fanfare und lustiger Marsch) (Einleitung) (Nur Bläser mit konzertierenden Contrabässen)

September 1895:

– (Zug zu Dionysos oder Sommer marschiert ein)Footnote 25

(28?) June 1896:

– Was mir das Felsgebirge erzählt.

Der Sommer marschiert ein.Footnote 26

28 June 1896:

– Pans Erwachen.

Der Sommer marschiert ein.Footnote 27

6 August 1896:

– Einleitung: Pan erwacht.

Nr. 1 Der Sommer marschiert ein. (Bacchuszug).Footnote 28

In the fair copy of the score (Albrecht 1147 B), Mahler wrote:

Einleitung: Pan erwacht

folgt sogleich

Nro. 1

Der Sommer marschirt [sic] ein / (‘Bachuszug’) / Partitur.

And in the same source, Mahler provided titles for the key motifs of that first part, here given with the respective bar numbers in the final score:

| Der Weckruf! | [bar 1 of the symphony/movement] |

| Pan schläft | [bar 132] |

| Der Herold! | [bar 147] |

| Das Gesindel! | [bar 539] |

| Die Schlacht beginnt! | [bar 583] |

| Der Südsturm! | [bar 605] |

The first three indications belong to what was supposed to be the introduction, but later became integrated into the first movement. ‘Der Weckruf!’ refers to the grand opening with eight horns, itself a sort of introduction to the introduction; ‘Pan schläft’ stands above four-flutes-plus-strings chords and the subsequent oboe solo; and ‘Der Herold!’ refers to the E♭ clarinet part. Among these motifs, two appear in Steinbach 1896 in ink but without names:Footnote 29

| Pan schläft | [bar 81 (of the manuscript), side c, 3rd system, staves 1 and 2)] |

| Der Herold! | [bar 97, side d, 1st system, stave 2)] |

The entry in pencil at the very end of Steinbach 1896 that directly mentions ‘Pan schläft’ – the ‘Wieder erstes […]’ inscription described above – is of particular interest here. It was obviously added later than the main content. The entire inscription, crossed out in Steinbach 1896, appears word for word, note for note, in ÖNB 22794, where, however, it is not crossed out. As is thrillingly obvious, this well-known and much discussed document is chronologically, thematically and structurally the direct continuation of Steinbach 1896. This fact makes it necessary to regard these two documents as a single and coherent unit.

ÖNB 22794 was acquired by the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek through a purchase by a person named Köhler (who has not been further identified) on 3 December 1940. It is conserved in a hardcover folder bound with linen cloth and made specifically for this item.Footnote 30 The folder contains on cut graph paper the following description of the document:

III Symphonie / erste Skizze / drei Seiten / von Gustav Mahlers / Hand / Alma Maria Mahler.Footnote 31

It is written in Alma’s lavender ink, as used on the visiting card accompanying Steinbach 1896 and on nearly everything else she wrote. Just as in the case of Steinbach 1896, Alma erroneously refers to the sketch as ‘erste’.

Three sides of the manuscript bifolio ÖNB 22794 contain Mahler’s writing, in ink and pencil, while the fourth contains only empty staves. In terms of content, the manuscript can be divided into two sections: one consists of sides a and b and contains material for bars 164–238 of the completed score along with the much-discussed quotation from the lied Das himmlische Leben, which at the time was apparently still a part of the concept. The lied quotation transforms into the material for bars 150–63, which closes the page and this section of the document. It is a remarkably consistent and coherent draft sketch in four-stave systems, five on each side.

This first section of the manuscript can therefore itself be divided into two subsections: the first containing the eventual material for bars 164–238, the second starting at the fifth bar of the second system on side b with the indication ‘C-dur’ and the beginning of the Das himmlische Leben quotation.

Interestingly, the first subsection of ÖNB 22794 is much closer to the final score than Steinbach 1896 in terms of the number of bars (75), though not necessarily in terms of content (overall, Steinbach 1896 has 113 bars as against 143 in the final score). It starts precisely where Steinbach 1896 ends, with not a single bar missing between the two, providing a solid basis for the hypothesis that ÖNB 22794 is Steinbach 1896’s direct continuation. Everything is there, along with the famed trombone solo, just as in the final score. At the last system on side a, above the last six bars (corresponding to bars 219–24), Mahler wrote ‘Pan schläft!’ and the insertion symbol ‘V’. The inscription is in ink and the words are underlined. Another entry, this time in pencil, stands at the end of side b: it is the very same ‘Wieder erstes […]’ inscription that is found at the end of Steinbach 1896; here, however, it is not crossed out, and ‘Pan schläft!’ is underlined again.

The second main section of ÖNB 22794, the last notated page, side c, is in a much more fragmentary form consisting mostly of three-stave systems and containing various ideas, including some for the material that would appear later in the movement at bars 436–40 and 463–81. In the third system, Mahler made a pencil reference to the march, followed by ‘etc’ – suggesting that the theme had already been sketched in a different manuscript.Footnote 32 The manuscript in question could well be page 7 of Stanford 631 (dated 1895), which contains the march along with the thematic element referred to by Mahler in ÖNB 22794. Another pencil entry on the same page of ÖNB 22794, fourth system, shows a variant of the trumpet motif which in the final score first appears at bars 30–3 and is stated in the second system of side a of Steinbach 1896. If we accept that Steinbach 1896 was written first, this pencil entry would mean that Mahler wrote the motif down in ÖNB 22794 in order to use it again later in the movement (as he eventually did).

The dating of ÖNB 22794 has had its own evolution. Susan Filler placed the document along with the Stanford manuscripts in the summer of 1895, on the basis of the third page of the manuscript which, according to her analysis, is very much in the style of the Stanford pages.Footnote 33 Rudolf Stephan assigned it to the time of composition of the Second Symphony.Footnote 34 The reason for this and other dating hypotheses for the most part lies in the quotation from Das himmlische Leben, which led scholars to connect the sketch to the composition of the song, on the basis of the somewhat inaccurate content of the quotation. Friedhelm Krummacher speculated that the quotation in such a form would not have been possible if the song had been finished at the time of its insertion in ÖNB 22794.Footnote 35 Edward Reilly was the first to refer to Bauer-Lechner’s remark about Mahler composing the introduction to the first movement while waiting for the sketches from Behn.Footnote 36 Reilly offered it as a clue that ÖNB 22794 was written later than generally thought, although he too left open the possibility that it dated from the summer of 1895.Footnote 37

Another curious detail is that with the exception of Morten Solvik, none of the scholars who have written about ÖNB 22794 have mentioned the number ‘2’ written by Mahler in the top right corner of side a.Footnote 38 Solvik successfully avoided seeing ÖNB 22794 as an isolated manuscript with assorted content. He argued that the crucial piece of information for a dating of the manuscript to summer 1896 is that before that time, Mahler made absolutely no mention of stillness and lifelessness with regard to the winter/sleep thematic cluster, quoting as proof the same passage in Bauer-Lechner’s memoirs mentioned by Reilly.Footnote 39 It is indeed peculiar that practically no one else considered that passage as worthy of closer examination. Solvik followed the remark about programmatic clues to the origin of ÖNB 22794 with the view that,

The manuscript may, in fact, constitute the second of two bifolios in which Mahler completed a particell sketch of much of what would later become the first theme area in the final version of the movement. In the upper right-hand corner of page a we find the number ‘2’ (or possibly ‘3’).Footnote 40

This is a logical assumption based on the available evidence. Now that we have Steinbach 1896, it is clear that it is the first of the two bifolios referred to in Solvik’s hypothesis, whereas ÖNB 22794 is its direct continuation, written in all probability immediately afterwards, perhaps even the same day, but certainly during the crucial week of 12–19 June 1896. The analysis and the discussion that follow will present the evidence that connects these two manuscripts, and will attempt to prove that they can and should be considered as a single, perfectly matched and coherent unit.

The paper of ÖNB 22794, like Steinbach 1896, has no watermark. As Table 1 shows, the physical measurements of the two sources are very similar, the minor differences being the result of trimming (also the reason why the dimensions are not identical from one end to the other within the same manuscript, the difference being only a few millimetres). The ink is the same in both manuscripts, with the paper of Steinbach 1896 showing the same acid deterioration as ÖNB 22794, although the former is overall in a better condition. Both manuscripts contain ink and pencil entries.

If we consider the documents as one unit, many things in ÖNB 22794 become clearer. ÖNB 22794 includes no time signature, clefs or tonality indications.Footnote 41 All these elements are missing from ÖNB 22794 for a very simple reason – they are all in Steinbach 1896, at the first system, along with the instrument groups assigned to each stave. The writing in ÖNB 22794 seems to have gone more smoothly than that of Steinbach 1896 and the material is much more consistent.

Apart from the issue of Das himmlische Leben, another section of the manuscript has introduced considerable confusion into attempts to define the order in which particular sections and thematic elements came into being. The part in question consists of the 15 bars that close Steinbach 1896 and appear in ÖNB 22794 in C major, corresponding to bars 150–63 of the final score.Footnote 42 Given that the content follows a different order from that of the final version, and given the absence of other relevant sources, the emerging picture was unclear and allowed for different interpretations. For example, the material at figures 11–13 can deceive the observer into thinking that it was written later than what comes before it in the sketch, and after it in the final score, and can also lead to the conclusion that it was the first version of that material. John Williamson, for instance, hypothesized that the original beginning of the introduction was the beginning of ÖNB 22794, figures 13–18 (representing the awakening of Nature), followed by figures 11–13 (with their suggestions of ‘Summer marches in’).Footnote 43 Such a scheme makes sense only if we consider ÖNB 22794 to be an isolated document, with no connection to any other. However, Steinbach 1896 suggests a different outline, with this material (from figures 11–13) present in both documents, albeit in different tonalities. There is more than one possible explanation for this. One is that Mahler wrote Steinbach 1896, started ÖNB 22794, reached the transition after ‘Pan schläft!’, quoted Das himmlische Leben, and decided to put figures 11–13 as a continuation, thinking it might fit (or simply to see how it might fit) in a different tonality. Another possibility is that Mahler wrote content in both documents in the way in which he originally thought it should sound. In relation to this particular material, an interesting detail in this section is found in the second system of side d of Steinbach 1896, on the stave for cellos/double basses, at bar 103 (bar 154 of the final score). Under the corresponding bar in ÖNB 22794 Mahler wrote ‘Contrabs’ (double basses) in ink. In Steinbach, he wrote ‘Cra[?] Bäße’, again in ink. However, there is a significant difference: in Steinbach 1896 the content is written an octave higher than in both ÖNB 22794 and the final score. Using pencil, Mahler wrote ‘8 ∼∼∼∼∼∼’ under the bar, indicating that it should go an octave lower than originally written. It was obviously added later and, given the body of evidence, most probably after the writing of the material in ÖNB 22794.

Two bars written in pencil, relating to the piccolo part, appear in both manuscripts. In Steinbach 1896, the relevant bars are the equivalent of the piccolo at bars 249–50 of the final score and are to be found in the trumpet stave above the equivalent of bars 150–1, manuscript side d, second system, bars 1–2. ÖNB 22794 displays the equivalent of the piccolo at bars 251–2 placed one bar further on (that is, above the equivalent of bars 151–2) and broken up differently from the final score. Example 2 shows the variants between the two manuscripts.

Example 2 Piccolo figure as presented in (a) Steinbach 1896 (where the division across bars corresponds to that in the final score) and (b) ÖNB 22794.

The ‘Pan schläft!’ entry found at the end of side a of ÖNB 22794 requires particular attention in the light of Mahler’s hermeneutic plans. The entry also contains the insertion mark, which could be interpreted as Mahler’s intention to insert the corresponding music at that point in the sketch. However, the theme described with the words ‘Pan schläft!’ is present later in the document, namely in the first system of side b.Footnote 44 One could argue, as Solvik did, that the words were a cue by Mahler to himself to insert that particular musical idea, which was done on the following page. Mahler then crossed out the words in Steinbach 1896, as he no longer needed the reminder.Footnote 45 The fact that the words were written in ink speaks in favour of this hypothesis. However, there are a few things to consider. The thematic element in question was first stated in Steinbach 1896, but without text above the notes. There is no evidence that Mahler mentioned Pan at any point before June 1896. In fact, the first such remark on record is the one he made to Bauer-Lechner about the music he was working on corresponding more to Pan than to Dionysus:

Der Titel: ‘Der Sommer marschiert ein’, paßt nicht mehr nach dieser Gestaltung der Dinge im Vorspiel; eher vielleicht ‘Pans Zug – nicht Dionysoszug! Es ist keine dionysische Stimmung, vielmehr treiben sich Satyrn und derlei derbe Natusgesellen herum.Footnote 46

The remark is undated, but it is difficult to believe that Mahler developed a philosophical concept to the point of assigning a very particular image to a precise theme within the few days of nervous waiting for the parcel from Behn. It is more likely that it came about later, after the sketches had arrived and Mahler had started piecing together the structure of the first part of the symphony. Interestingly enough, the heading ‘Pan schläft!’ appears also on page 3 of Stanford 631, written over the fourth system on the page, above the first bar (bar 463 of the final score). It also contains the words ‘Naturlaut’ (‘sounds of nature’) and ‘Einleitung’ (‘introduction’). It seems that at that point Mahler intended the ‘Pan schläft!’ motif to appear a number of times through the movement, putting the words where he wanted the theme to appear. (He would change his mind regarding this particular page, but the decision to do so obviously belongs to a later phase of the work on the movement.Footnote 47 ) This is a very good moment to tackle the issue of the Stanford material, especially that of Stanford 631, and show how it relates to the first week of Mahler’s vacation.

If we keep in mind that the Stanford sketches contain – among other things, and most importantly for this study – fragments of the summer march material, what we have in Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794 is a significant portion of the structure of what later became the first movement. The question that still needs to be answered is: what was in the sketches Mahler asked Behn to send from Hamburg? The Stanford material contains a dedication by Mahler to Bauer-Lechner, to whom he gave the sketches. The dedication states:

Steinbach am Attersee

On 28 July 1896 the curious thing happened that I was able to give my dear friend Natalie the seed of a tree which nevertheless already blossoms and flourishes in the world fully grown, with all its branches, leaves and fruit.

Gustav Mahler.Footnote 48

If Mahler considered those sketches to be the very first ‘germs’ of the symphony, and if we take into account that they contain march material from the first movement, the core of what became the marching summer thematic cluster, the appearance of Steinbach 1896 and its indisputable connection with ÖNB 22794 open up further possible hypotheses. We have already seen that those documents, written in June 1896, contain the complete winter/sleep thematic elements, and the body of evidence shows quite clearly that the material sketched in them could not have been conceived in 1895. It might be not too far-fetched to think that the Stanford material – or at least the part of it that relates to the first movement – could be the sketches that Mahler implored Behn to send from Hamburg. Reilly suggested that the Stanford sketches might be all there was of the first movement, noting the choice of words for the dedication to Bauer-Lechner as compared to a letter to Behn of 11 July.Footnote 49 In the first half of the letter, Mahler gives some information about the completion of the draft of the first movement, entitling it ‘Der Sommer marschiert ein’, and in the second half he again expresses his gratitude for Behn’s promptness in fetching the forgotten sketches and sending them to Steinbach:

You, dear Hermann, have honestly contributed to [the completion of the movement]; without the sketches, I couldn’t have begun. I am really heartily grateful. To you these few pages with notes seem quite insignificant. But they contain (following my way of sketching) all the germs of the now fully grown tree and I hope that you will feel thanked for your effort by surveying the whole. Once again, heartiest, undying thanks!Footnote 50

The letter is significant for several reasons. When writing about the completion of the movement, Mahler lists the title ‘Der Sommer marschiert ein’, which, as we know from other sources, was the movement’s title even in the fair copy, even though the part Mahler considered to be the introduction was indicated with a separate title. Owing to the structural change, there was no separation between the two sections in the score and no indication as to where one ended and the other began. The part of the symphony based on the sketches was precisely what Mahler at that time considered to be the first movement, so he made no mention of the supposed introduction. The letter quoted above corroborates the chronology of events established earlier in this study. Mahler was unable to start work on the first movement and focused instead on the summer march before he had the sketches in hand, and outlined the introduction (with what later became the winter/sleep thematic cluster) while waiting. Mahler also refers to a ‘few pages’, suggesting that the material in question was not extensive but nevertheless contained ‘all the germs of the now fully grown tree’. Since these words are in the letter of 11 July and the dedication to Bauer-Lechner contains a nearly identical expression – ‘the seed of a tree’ and ‘fully grown’ – it is very likely that what she received was indeed the ‘few pages’ Mahler was so desperate to get. In his letter of 18 June 1896, Mahler did promise Behn that he would give him the sketches as a token of his gratitude, but in the letter quoted above he does not repeat the offer. It is quite possible that he had forgotten his promise in his joy over having finished the symphony, and that he gave the sketches to his other friend instead. We will probably never know exactly what happened, but considering Mahler’s forgetfulness on other occasions and with Steinbach 1896 to prove the birth of the winter/sleep cluster, this hypothesis seems entirely plausible.

Taking into account the above evidence, the verbal indications in Stanford 631 (‘Pan schläft!’ and ‘Naturlaute’, in ink) were probably written at some point in June 1896 – that is, once Mahler had received the sketches, having already drafted the introduction (hence ‘Einleitung’) and gone on to develop the Pan concept (hence ‘Pan schläft!’). This may indicate that Mahler returned to the Stanford sketches with a pen later to add some new ideas. He may have written ‘Pan schläft!’ on side a of ÖNB, forgetting to turn the page and therefore overlooking that the theme was already there. Once he realized that, he returned to the sketch and crossed out the heading. He could have done so within the next five minutes, or equally well five days later. This brings to mind another entry, the ‘Wieder erstes […]’ written in pencil, which appears both in Steinbach 1896, where it is crossed out, and in ÖNB 22794. The meaning of this note, too, has been interpreted in various ways. Williamson saw it as a clue indicating the place where the page 1 material returns. Solvik’s suggestion that Mahler left notes to himself about elements of material developed elsewhere that still has not been found is probably closer to the truth.Footnote 51 What is clear is that Mahler returned to both manuscripts with a pencil, as was his habit. That the ‘Wieder erstes […]’ material is crossed out at the end of Steinbach could suggest that Mahler put it down there first and then decided that it might fit better after the second page of ÖNB 22794. Another perfectly viable possibility is that Mahler wrote it on the wrong page first and then moved it to its correct position. Both sketches contain variants of the material from figures 11–13, and in a hurry Mahler could simply have overlooked the rest of the sketch.

Steinbach 1896 contains the first statement of the entire winter/sleep cluster, minus the elements from the very beginning of the completed movement, which are the Weckruf and a variant of the ‘oscillation’ from the fourth movement. Literally every other important thematic cell is there, including the first appearance of the summer march material that is soon suffocated because it is too early for the summer to march in. The whole structure as presented by Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794 (in the latter consistently on sides a and b and in scattered fragments on side c) is nearly identical to that of the finished movement, which suggests that Mahler had the building blocks already well worked out in his head. The solo parts (violin in Steinbach 1896 and trombone in ÖNB 22794) are also written out clearly and are identical to their equivalents in the complete score. The summer march had already been thought of and its most important features written out, but it is only with the material from Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794 that the movement really starts to take on the shape we know today. As I have already pointed out, in order to assess these two documents and their impact on the composition of the first movement, they must be viewed as a single unit. The fact that the equivalent of bar 239 in ÖNB 22794 does not lead into the first appearance of the summer march material but into Das himmlische Leben supports the conclusion that at the time of writing Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794 (that is, before 19 June 1896), these two sketches constituted the introduction to the first movement proper. At that time, the march material was supposed to be included only at the beginning of the first movement. However, once Behn arrived with the sketches, Mahler changed the structure of the movement and combined the introduction and the march to form the opening of the symphony.

2.3 The ‘O Mensch!’ problem, the Weckruf and the sixth movement

Among the most interesting elements in Steinbach 1896 is the material at the bottom of side d, which represents a variant of the introductory bars of the fourth movement. Today, this particular element, the ‘primeval oscillation’, as Peter Franklin called it,Footnote 52 connects the Weckruf and the timpani/bass drum/trombones section and is found between bars 14 and 23 of the final score (marking the arrival of figure 1 and the beginning of Steinbach 1896 respectively). In the manuscript, however, it is merely jotted down over a system of two staves (the upper containing no notes), plus one stave containing chords found between bars 11 and 14, and again between bars 178 and 181. There is no clef, tonality or metre indication at the first bar, but two metre changes – 3[/2] and 2[/2] in bars 8 and 9 respectively – are written in the empty stave above.

Mahler completed the draft score of the fourth movement in the summer of 1895. In the Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, a set of three movements (the third, fourth and fifth) in draft score is catalogued under the call number Cary 283.Footnote 53 At the end of the score, at the last page of the fifth movement, Mahler wrote:

Sontag August 1895

Ferienarbeit beschloßen.Footnote 54

In a letter to Arnold Berliner of August 1895, Mahler indicated that he had all but the first movement ready in draft score.Footnote 55 In the fair copy of the score, however, there is, unlike for the other parts of the symphony, no precise completion date for the fourth movement.Footnote 56 The manuscript preserved at the Library of Congress in Washington DC, dated summer 1896 by Mahler himself, adds some confusion. It is a piano draft that does not correspond exactly either to the fair copy or to the final score, and the date given by Mahler as well as the content suggest that it was written after the orchestral draft. This piano reduction – under the circumstances, this would be the more accurate term – is closer to the final version than is Cary 283. The fourth-movement material in Steinbach 1896 (see Example 3) differs from both, and the fact that it is in ink seems to suggest that it was written along with the rest of manuscript, which would place it chronologically between the two versions of the fourth movement. However, it is not entirely impossible that Mahler wrote it later, as was the case for ‘Pan schläft!’ in ÖNB 22794. The beginning is obviously different, as it has two extra bars. The content of bar 4 is shorter by two crotchets, the metre (not indicated) being 2/2, not 3/2 as in the final score, or 6/4 as in Cary 283. One explanation could be that Mahler was writing down one possibility for the integration of the material into the introduction to the first movement he was composing, but even so it stands out as a peculiarity. Bar 15 (the equivalent of bars 5 and 6 in the final version of the movement) is in the same metre as Cary 283 (8/4), although this is not specifically indicated, whereas the Library of Congress piano draft/reduction has that bar divided in two (in 2/2 metre), just as in the fair copy and the final score. Overall, the content appears to be a combination of different blocks of material between the beginning and bar 17 of the fourth movement.

Example 3 The fourth-movement material on side d of Steinbach 1896 (first stave only).

The presence of this material in Steinbach 1896 at this point (at the bottom of the last page and disconnected from the rest of the music in the document) and in this form allows us to answer several significant questions that we were not able to tackle properly before this discovery. An obvious first conclusion, considering that a version of this material precedes the beginning of Steinbach 1896 in both the fair copy and the final score, is that Mahler already at that stage intended to insert some ideas from the fourth movement into the introduction to the first movement and jotted down a possible solution. The chordal sequence of the ‘O Mensch!’ material displayed on the single stave at the bottom of side d in Steinbach 1896 appears also in ÖNB 22794, side a, second system, in a more or less complete form. This could mean either that Mahler wrote the staves in Steinbach and then decided to include the chords in the continuation of the draft (ÖNB 22794), or that the idea of using all the material came from having used the chords in ÖNB 22794 and he wrote the extended theme into Steinbach for later use. There is no document that can fully support either of the two hypotheses, especially since all these entries were made in ink and we really do not know with certainty in which order events occurred. Be that as it may, what is clear is that at that point the symphony was obviously to begin in the way reflected in Steinbach 1896 – with seven bars of music for the bass drum and then the trombones. This further indicates that during the writing of Steinbach 1896, Mahler had not yet intended the Weckruf to be where it stands today, which implies that this theme as we now know it was added to the symphony later that summer.Footnote 57 Hermeneutical background supports this hypothesis: if the symphony were to begin with the marching in of summer, as Mahler initially planned, the world he was depicting would have to be already fully awake. However, when the introduction dominated by the winter/sleep elements was added, everything was still asleep, so to speak; a wakeup call became necessary, and just as with any wakeup call to someone fast asleep, it could not take immediate effect. The introduction, therefore, was designed as a gradual awakening of a lethargic nothingness, and once that became clear, the Weckruf – the ‘wakeup call’ – was added to the programmatic concept. Following this, we can connect the addition of the Weckruf theme to the phase following Mahler’s decision to shape the introduction around the sleeping Pan and his awakening. Some remarks made by Bauer-Lechner in the days during which Mahler finalized work on the symphony thus require a new reading. Among her notes for the important day of 28 July 1896 we find the following:

When I came back from my morning ride and my hour in Attersee, Mahler came to meet me. I jumped off my bicycle, and as we walked home he told me that he was happy and satisfied with the work, except for the beginning, which still did not altogether please him.Footnote 58

Two days later, on 30 July, she wrote:

However, Mahler succeeded today in revising the beginning of the first movement so that it had the required effect at the head of this monumental introduction. ‘In fact,’ he said, ‘I had to set about it exactly like a master-builder arranging the units of his building in the right relationship to each other. By doubling the number of opening bars (that is, by making it go at half speed in an adagio tempo) I have now given this part the necessary weight and length.’Footnote 59

The question raised by this passage would be: what, then, was the real beginning? Franklin suggests that the changes might have been related to the Weckruf and were later abandoned.Footnote 60 William McGrath conjectured that the changes brought about the Weckruf as we know it today, indicating also that the decision to incorporate them may have had something to do with the fact that Mahler was supposed to meet his friend Sigfried Lipiner that day.Footnote 61 However, a further detail could open the possibility of another interpretation. In the English translation of the excerpt quoted above, Bauer-Lechner’s term ‘Schwere’ is translated as ‘weight’. However, ‘weight’ in this context changes its meaning. ‘Schwere’ in German means ‘heaviness’ or severity, gravity (seriousness), whereas the equivalent of ‘weight’ would be ‘Gewicht’. In the context of Mahler’s sentence and having in mind the mood of the beginning of the symphony, it is more likely that the word refers to heaviness, which is also supported by the indication in the score (fair copy and final version) over figure 2: ‘Schwer und dumpf’ (‘heavy and dull’). This offers two distinct possibilities: (1) as Franklin suggests and with the Weckruf in place, Mahler doubled the note values of the opening horns but later changed his mind; (2) the opening did not yet have the Weckruf and Mahler was working on a beginning that was either the ‘O Mensch!’ material or the beginning of Steinbach 1896. For the Weckruf to function as intended, it could not have been at the Adagio tempo referred to by Mahler. Indeed, the description over the Weckruf’s first bars (in both the fair copy and the final version) says ‘Kräftig. Entschieden’ (‘Vigorously. Firmly’). Immediately after the horns, over their closing semibreve bars and the trombone and tuba chords preparing the ‘O Mensch!’ theme, the indication changes to ‘Zurückhaltend’ (‘Restrained’) and the cue that brings the ‘O Mensch!’ theme has ‘molto riten[uto]’. The beginning of the fourth movement has ‘Sehr langsam’ as the tempo indication, so it is hard to imagine that it could be more ‘langsam’ than it already was. In their extensive conversation of 1 July, Mahler told Bauer-Lechner:

It all tumbles forward madly in the first movement, like the gales from the south that have been sweeping over us here recently. (Such a wind, I’m sure, is the source of all fertility, blowing as it does from the far-off warm and abundant lands – not like those easterlies courted by us folk!) It rushes upon us in a march tempo that carries all before it; nearer and nearer, louder and louder, swelling like an avalanche, until you are overwhelmed by the great roaring and rejoicing of it all. Meanwhile, there come mystical presentiments – ‘O Mensch gib Acht’ (from the Night) – as infinitely strange, mysterious interludes of repose.Footnote 62

Clearly, at that point the ‘O Mensch!’ material had already been integrated into the movement, but Mahler did not specifically mention the appearance of that same material at the very beginning of the symphony. Since no manuscripts are available that could tell us what Mahler changed at the end of July, we have to speculate, but given the facts listed, the idea that Mahler was modifying what follows the Weckruf rather than the Weckruf itself should not be disregarded as a possibility.

The day after altering whatever was planned at the beginning of the symphony at this point, Mahler turned to the last movement – more precisely, its ending. As Bauer-Lechner reports:

This morning Mahler changed the ending of the Adagio of the Third, which for him was not straightforward enough. ‘The whole thing now sounds in broad chords and solely in the one key of D major’, he said to me.Footnote 63

There could be multiple reasons for this intervention, one of them being that Das himmlische Leben was no longer included and that the Adagio had become the closing movement. The song was eliminated from the concept probably before Mahler finished the draft of the first movement at the end of June 1896, but first the structure of this section had to be finished. Only then could he switch to what had become the climax of the symphony to tidy everything up and connect the loose ends. An interesting detail in this sense is the foliation in the fair copy of the movement. The numbered folios jump from 5 to 8, although the music shows no inconsistencies. One could argue that folios 6 and 7 contained material that Mahler later eliminated, but the continuity of the music makes this seem less likely. If he did discard references to Das himmlische Leben or anything else substantial enough to cover two entire folios, he would probably have done so before starting work on the fair copy of the movement, which was finished in November 1896.Footnote 64

3 Closure and aperture

The reconstruction of the compositional process has come a long way since the first systematic analyses of the known primary sources for the Third Symphony, such as Filler’s 1977 dissertation. Although more information is now available, it remains thin on the ground. There still is much to discover and much to understand, and the work will probably never be entirely finished. The appearance of Steinbach 1896 sheds new light on what the Mahler research community had at its disposal beforehand.

Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794 date back to one lively week of Mahler’s 1896 holiday in Steinbach am Attersee. The key thing about this period is that Mahler had left behind the sketches for the first movement in Hamburg and therefore could not work on it in the way in which he had intended, an issue that significantly influenced his mood during that week. However, he wasted no time and came up with an introduction to the first movement, which had not been a part of the concept before and therefore changed the structure of the first part of the symphony, along with its programme. The massive interaction of the winter/sleep thematic cluster with the marching in of summer was practically determined by Mahler’s forgetfulness. The sketches he needed arrived after he had written the introduction. It then took him less than ten days to finish the draft of the entire movement. The ‘introduction’ became a robust counterpart to the summer march, compared with the initial idea of an ‘easily dispatched opponent’,Footnote 65 thereby redefining the structure of the movement. The sources furthermore indicate that the beginning of the movement was composed in at least two different phases – the one reflected in Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794, the other (if there were only two) being the addition of the Weckruf and the Pendel (‘oscillation’) from the fourth movement. The opening section itself is one of the crucial points of the entire first movement, but the first bars of Steinbach 1896 and the absence of these important elements from the beginning of the symphony in its final form show that the ‘patches’ used to integrate the material from Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794 are more than simple fillers.

The number of different programmatic titles for the movements of the Third Symphony says a great deal. Mahler kept changing them throughout the compositional process up to the printing of the score, when he decided to discard them entirely and label the symphony only by tonality. However, it would be wrong to assume that the music was composed to conform to the images Mahler had assigned to the individual movements. The insertion of the introduction into the first movement and the circumstances in which this occurred allow us to question any strict separation of music from visual/programmatic elements. Steinbach 1896 and ÖNB 22794 suggest a different kind of relationship between image and music: the image does not condition the music, but the music does not stand alone. Image and music interact and the product of their correlation and dynamic exchange is a complex unit that requires a multilayered approach.