Thetis, the sea nymph to Achilles, her son by Peleus:

Only yesterday Zeus went off to the Ocean River

To feast with the Ethiopians, loyal, lordly men,

And all the gods went with him. But in twelve days

The Father returns to Olympus …Footnote 1

Dido's sister is persuading her to let flow her passion for Aeneas:

Do you believe

This matters to the dust, to ghosts in tombs?

Granted no suitors up to now have moved you,

Neither in Libya nor before, in Tyre –

Iarbas you rejected, and the others,

Chieftains bred by the land of Africa

Their triumphs have enriched – will you content

Even against a welcome love?

Iarbas, Dido's African suitor curses her:

Her twisting course

Took her [Rumor] to King Iarbas, whom he set

Ablaze with anger piled on to anger

Son of Jupiter Hammon by a nymph,

A ravished Garamantean, this prince

Had built the god a hundred giant shrines,

A hundred altars, each with holy fires.Footnote 2

Omi, omi lènìyàn Humanity is tide

Bó bá ṣàn wá Now it flows hither

A tún ṣàn padà Now it flows thither

The term ‘crossroads’, most commonly used to gloss the Yorùbá lexical item orı́ta, does not adequately convey its meaning. In addition to any number of access ways and paths converging into orı́ta, orı́ta serves, in its own right, as a veritable arena of encounter, an arena of contact among beings, and for the exchange of goods and values. Each access way or path vanishes – or, better still, merges – into orı́ta in a manner similar to the estuaries of a river emptying themselves into a basin, a sea or an ocean, which may be traversed to enter into another access way. Orı́ta, it bears repeating, is not a point; it has dimensions; it is a space, an arena defined by encounters and exchanges. That is why, in Yorùbá cosmology, the centre point of orı́ta is the liminal domain of Èṣù, the custodian of àṣẹ, the primordial life force; Èṣù, the ultimate arbiter among beings – indeed, among all forces.

This article assumes and argues that through the ages, stretching beyond any contact with proselytizing faiths and mercantile aliens, the Bààtonu peopleFootnote 3 have tended the geophysical entity Borgu. This straddles the frontiers of Nigeria and the Republic of Benin, and the Bààtonu turned it into the orı́ta for all the cultures of the sub-region bounded by the southward sweep of the River Niger from its deepest penetration into the Sahelian region.Footnote 4 This has given rise to many consequences addressed by scholars since Parakou and Nikki. Studies have found that many communities and ‘city states’ among the YorùbáFootnote 5 embrace, with pride, accounts of Bààtonu founding heroes and princes. The Bààtonu have offered hospitality to disaffected, dissident and defaulting Yorùbá princes.

Borgu is so situated in relation to the Yorùbá world that the Yorùbá adage ẹni tí a sùn tì là á jarunpá lù (the one we sleep next to is the one we hit when we stir and kick in our sleep) applies to their association and inter-relationships down the ages. Thus, when ambitious princes and entrepreneurs among the Yorùbá wanted to establish contact with cultures to the south-west, to the far west, and beyond Odò Ọya, ‘the River Niger’, Borgu served them as orı́ta, as defined above. It therefore raises more than mere intellectual curiosity that the ‘post-contact’Footnote 6 storytellers of both the Yorùbá and the Bààtonu embrace myths of a Middle Eastern origin in the same way as they embrace those of all the Mandinka and kindred cultures that claim the Sundjata epic (Sisoko 1 and 2). As the Yorùbá omi lèníyàn excerpt above suggests, it is by no means self-evident that any or all of the peoples in the sub-region of West Africa could not have migrated from the Middle East – or from anywhere else, for that matter. Yet, in the context of the socio-political history of the sub-region in the last millennium, the plausibility – not to say the ‘validity’ – of these myths is very important for our self-concept, and, indeed, for our proper orientation in a world that is fast evolving into one single global village. In the new world order, we have to deal with more than a mere romantic notion of individuality, a notion that assumed the grotesque proportion of ‘nationality’ in nineteenth-century Europe.

How do we test these received myths for validity? How do we identify strands of our adopted essence that link Borgu with the Persian Kisra, the Yorùbá with Lámúrúdu (Nimrod), and the Mandinka Sundjata with Bial, an illustrious associate and fellow Semite of Muhammad, Peace be unto Him? How many millennia did it take to engender the culture of the Bààtonu, a people whose once robust population has declined to no more than 400,000 within Nigeria, but that still straddles the Benin–Nigeria border? How many millennia could it have taken to engender the common culture identified with the 30 to 40 million persons in the homeland alone, speaking some twenty-five forms of the Yorùbá language, with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility? How we answer these questions has consequences for the perceived stature of the two peoples discussed in this study, in the context of a fast-globalizing planet. The answer we proffer will determine the extent to which we assume responsibility for our existential reality: who we believe we are; who we accept as neighbours to whom we owe a duty of care; what fate has thrown us together; and how the resulting interpenetration has remade us before and since the Berlin Conference of 1884–85. These are no mere rhetorical questions. They are important because, as far as we can see, the future is infinite and our past conceptually finite, but both are enumerable. The time has come to turn to accessible phenomena and institutions in order to recover the crucial sense of our past; to reassess our present reality; and to chart our path to the future.

I suggest that the most reliable source of material for testing the plausibility and/or validity of the post-contact narratives of our essence is our lore, transmitted through language, and that we should interrogate and creatively re-enact our story for posterity. By ‘language’, I do not mean isolable morphemes and lexical items, although one may consider them symbols par excellence that embody significant memories. Despite being symbols par excellence, they unfortunately tend to codify only discrete etic meanings, and, for that reason, they travel very light. Linguistic processes and rules of grammar – to the extent that they, too, are definable – are also arbitrary. They, too, are therefore symbols. They should hold traces of our antecedents. Here again, however, I entertain a huge dose of scepticism. The phonological process of vowel harmony, for example, is a rule-governed linguistic gesture whose scope includes complexes of morphemes and/or whole phrases in languages. Vowel harmony, however, may arguably spread among contiguous languages with but scant regard for extra-linguistic conditioning. Therefore, like other rule-governed language gestures, it, too, offers limited insight into our past.

The kind of macro-linguistic items that I wish to consider below contain too many experiential components to be easily diffused outside tangible defining contexts. They encapsulate consequences for a people – and, certainly, for peoples – in a situation of culture contact. I therefore propose that we interrogate critically the structure, reference and mode of functionality of each item. In the case of the Bààtonu and the Yorùbá, if we ask how long any set of such items may have taken to differ significantly from each other, if that is the case, or how long they took to acquire typological similarity, if not similarity of form, meaning and usage, we may have reason to be gratified by what we learn about these two peoples. And at least our meaning will be wholly ours.

But why should one undertake such a laborious task for the purpose of self-gratification about historical antecedence and relatedness? The passages at the beginning of this article offer us a compelling reason. Thus, the bard Homer suggests that the Greeks of at least the eighth century BCE were fully aware of, and traded with, the Ethiopians of the Abyssinian highlands. And we know that the Romans were aware that rich African kingdoms lay beyond Carthage and the land of the North African Garamantes. Robin Law (Reference Law1980) conjectures that the Garamantes had horses in the fifth century BCE, and we know that the famous Carthaginian general Hannibal crossed the Alps into Italy with 26,000 troops, with 6,000 horses and with elephants during the Second Punic War, c.218 BCE. It is safe to suggest, therefore, that the lands that supplied Hannibal with elephants, lying south of Carthage, could have adopted horses without having to wait for them to be introduced by proselytizing Islamic invaders almost a millennium later.

We may assume, however, that this line of reasoning will end in a historical cul-de-sac, since it is not inconceivable that the irretrievable desiccation of the Sahara desert post-dated Hannibal,Footnote 7 so that the land or lands that supplied him with elephants lay accessible to Carthage from the south. That would still not leave us with much to support a Persian origin for the Bààtonu, and certainly not an Egyptian or Judaic one for the Yorùbá. And we would still be interested in what the lore of both the Bààtonu and the Yorùbá allows us to deduce about their common and/or separate past.

Let us now interrogate macro-linguistic elements for an insight into what may lead us into the choppy waters of a plausible external history of our two peoples. Where I do not provide comparative data from both languages, I wish to suggest that, in most cases, the data adduced here will still be valuable for our objective. They will, hopefully at least, suggest leads for future inquiry.

The numeration system

What can we deduce from the data in Table 1? It is clear that, contrary to the impression that Sanúsí seeks to give (namely, that the Bààtonu numeration system is base five or quinary), the reality is not that simple. Bààtonu operates a system that, as in Yorùbá, combines a number of bases: five, ten and twenty (i.e. quinary, decimal and vigesimal). They both employ the arithmetical processes of addition and subtraction. It appears, however, that Bààtonu gives primacy to addition anchored on base five. Our interest here is the historical – or diachronic – implication of the differences observable between the two systems. What is the direction of change?

Table 1 Bààtonu and Yorùbá numbers

* Note: This suggests that Bààtonu does not add identical denomination and does not, unlike Yorùbá, count and/or name denominations in multiples using the number units two to ten, as in ogójì and ọgọ́ta.

Source: The Bààtonu data come from Sanúsí (Reference Sanúsín.d.).Footnote 11

If we subscribe to the heuristic supposition that systems do not normally change by adopting less productive, less generalizable operations or rules, it would appear that the Bààtonu numeration system is innovatory in relation to the Yorùbá system. In this regard, contrary to Sanúsí's notion of simplicity, which favours the subtractive ‘tẹ̀nan̄nẹsàrí’, the longer ‘yẹ̄n̄dū+kà+nọ̄ọ̄bù+kà+tía’ is both analysable and more generalizable, as shown in Table 1. How many days, years or millennia could it have taken Bààtonu to achieve even the minimal change we observe here? Would the resulting timeline challenge the validity of the putative date of the Persian origin of the Bààtonu people and culture, or of the Semitic provenance of the Yorùbá people and culture?

It is, of course, conceivable that one or both of these peoples migrated to their present locations and then subscribed to the culture and symbolic codification of the first to arrive, or, through some unknowable conspiracy, to the culture of a third group that we need to identify. The data below would imply a conspiracy hypothesis, which posits an improbable assembly of sages of a given generation among both peoples agreeing on a list of selective adaptations within a given time frame.

Names and naming

One of the areal semiotic features of the Niger–Congo cultures (read ‘languages’) is the use of kinship terms to refer to the notion of constituency. For example, fingers are ‘offsprings’ of the hand, ọmọ ọ ọwọ́ in Yorùbá. In a similar fashion, terms for body parts are used metaphorically to codify notions of location: for example, ẹnu un ọ̀nà, ‘mouth of pathway’, for ‘entrance’ (Yorùbá: ẹnu or ‘mouth’); etídò, ‘river ear’, for ‘river bank’ (Yorùbá: etí or ‘ear’); ẹ̀yìn ọ̀la, ‘back of tomorrow’, for ‘future’. Such areal features suggest that there might be a great deal more to gain from a systematic inquiry into macro-linguistic units, which gives folklorists no end of delight. I wish, therefore, to consider ‘name’ as the form, and ‘naming’ as its concomitant and culturally idiosyncratic ethnic or people-specific underpinning. I surmise that the names of people and the anthropocentric names of animals encapsulate world views and epistemological orientations of peoples; as a consequence, cognate relationships of form and meaning between any two distinct peoples based on these units should imply that there are more significant historical connections with diachronic implications than in cognate relationships distilled from discrete lexical items. In addition to these macro-units having referential meanings, each also defines the specific socio-psychological context of its usage. Since it is conceivable that one culture borrows only a form – or only a form and meaning – without its sociological context, a cognate relationship that includes the latter might suggest a more intensive or more sustained relationship over a greater length of time.

In this section, I present an overview of confirmable dog names, personal names and the nomenclature of interactions arising from kinship relationships among the Bààtonu and the Yorùbá. Within the Yorùbá group, Ṣàbẹ́Footnote 12 presents us with direct cognate relationships with Bààtonu. Any extrapolation of historical period from these relationships should enable us to consider critically the duration of contact in relation to the putative fourteenth-century Bààtonu migration from Persia.Footnote 13

First, the basis of naming in Yorùbá implied by the òwe (ẹ̀yínkùlé làá wò, ká tóó sọ ọmọ lórúkọ or ‘it is the backyard we must look to first, before giving a child a name’) appears to be common to both peoples and cultures. One may read this much from Wendy Schottman's observation:

Les noms baatonu contribuent également au renforcement de la structure sociale et a l'intégration de chaque individu dans cette structure. Ils permettent, par leur formulation et par les règles qui gèrent leur emploi, de reserrer les liens qui en ont le plus besoin. D'autres noms fournissent un support à la communication entre les puissances numineuses et les êtres vivants, en tant qu'acquiescement attentive ou élément d'une alliance propitiatoire. (Schottman Reference Schottmann.d.)

Bààtonu names also contribute to strengthening social structure and integrating each individual within this structure. They allow, by their formulation and by the rules that govern their use, a tightening of the links that need it most. Other names provide support for communication between the numinous powers and living beings, as attentive acquiescence or as an element of a propitiatory alliance.

Of particular interest for this study is the fact that Ṣàbẹ́ alone among the Yorùbá group appears to have adopted sets of Bààtonu naming customs, complete with lexical items and the cultural specificities they codify. I present only two areas here: anthroponyms of twins and birth order terms; and dog names. Of interest would be the plausible time of contact between Bààtonu and Ṣàbẹ́, given the latter's place in the myth of Yorùbá expansion as the most westerly of the sons of the people's eponymous progenitor Odùduwà, who lived and ruled in Ifẹ̀ Oòdáyé (i.e. Ilé-Ifẹ̀).

Naming and order of birth

Consider the data in Table 2.Footnote 14 The list presents the names of boys and girls with the same mother by order of birth. As all my sources note, the restrictions of uterine order result in siblings by different mothers bearing the same names within the same family, if they occupy the same position in the order of birth of children by their respective mothers. Palau Martí says the following about the Ṣàbẹ́ lists in Table 2:

Les noms de rang de naissance qui viennent d’être commentés représentent un emprunt au Bọkọ et au Borgou, ils existent à ṣàbẹ́ mais sont totalement inconnus de tout autre groupe yoroubaphone. (Palau Martí Reference Palau Martí1992, emphasis added)

The names of birth rank that have been commented upon represent a loan to Bọkọ and Borgou; they exist in Ṣàbẹ́ but are totally unknown in any other Yorùbáphone group.

It is certainly remarkable that this kind of naming does not occur in any other Yorùbá subgroup. For example, Ṣàbẹ́ shares with the rest of the Yorùbá groups the giving of ‘order of birth’ names to twins and to single children born after a set of twins, except that, in Ṣàbẹ́, another set of twins following a first set bear the names Ẹdọn or Akan.

Table 2 Borgu and Ṣàbẹ́ names by order of birth

Notice that the sixth male child in Borgu has an ‘order of birth’ name Woru meru, but no corresponding sixth name in Ṣàbẹ́, even though the Borgu one is the first name modified by a determinant. Even with this difference, how do we explain the Ṣàbẹ́ accommodation with Borgu? Do inter-group marriages explain it? How long could it have taken Ṣàbẹ́ to adopt this kind of blanket borrowing? We know that Ṣàbẹ́ is geographically surrounded almost entirely by Borgu. Given the critical regard the Yorùbá have for personal names and naming, encapsulated in orúkọ ọmọ ni íjánu ọmọ (the name of a child is the child's rein), what kind of cultural reorientation could account for this adoption?

If the ‘order of birth’ names have other referential meanings in Bààtonu, as Schottman (Reference Schottmann.d.) suggests they do, do the same meanings carry over to Ṣàbẹ́? Notice that Palau Martí takes care to mark the tones of the Ṣàbẹ́ forms but not the Bààtonu forms, perhaps in accordance with the conventional orthography of Bààtonu (see also Schottman Reference Schottmann.d.). Does this suggest that the forms have other semantic references, even in Ṣàbẹ́, than just the order of birth to the same mother? Again, one suspects that conclusions from these lines of inquiry would suggest a probable time of contact that pre-dates the fourteenth-century migration hypothesis.

Beyond names and numbers

The historical relationship between Ṣàbẹ́ and Bààtonu – and, by implication, between the entire Yorùbá group and Bààtonu – goes beyond names and naming. Consider kinship sociological terms and usage, for example. The term íyakọ (arguably derived from the noun phrase íyá ọkọ; literally, ‘mother of husband’) refers to a verbal play or joust between a woman married into a family, on the one hand, and, on the other, the siblings of her husband or the children of other wives in the household who precede the woman in their residence in the household. Parties to this verbal play address light-hearted insults to each other about their relatives while staying within a recognized limit of decorum. The joust reinforces affective relationships among those involved in the banter. Those engaging in the joust are said to jẹ íyakọ – literally, to ‘eat íyakọ’, as glossed above.

Now, consider what Palau Martí has to say about gonẹ̀ṣì in Ṣàbẹ́:

Jẹ gonẹ̀ṣì, litt., manger le gonẹ̀ṣì: cette expression implique l'exercise de certains droits à l'encontre de l'associé gonẹ̀ṣì; ces droits consistent en brimades et insultes qui peuvent dériver en voies de fait, mais c'est là le cas exceptionnel …

En effect, ici le gonẹ̀ṣí ne s'exerce jamais entre parents de sang; c'est la relation d'alliance qui doit se trouver à la base de ce mode d'association qui, par ailleurs, peut s'établir entre groups en dehors de toute référence à la parenté. (Palau Martí Reference Palau Martí1992)

Jẹ gonẹ̀ṣì, literally, ‘eat gonẹ̀ṣì’: This expression refers to the custom that grants practical licence in face-to-face encounters among family members in relationships of gonẹ̀ṣì. This licence consists of the apparent freedom to address to one another potentially embarrassing statements and insults, some of which, in exceptional cases, may be based on facts.

In reality, gonẹ̀ṣì in this context never takes place among members related by blood; rather, relationships or ties by marriage may serve as the basis for association beyond anything that has to do with blood or birth.Footnote 15

Strangely enough, the term gonẹ̀ṣì is a Bààtonu loanword into Ṣàbẹ́. Its Ṣàbẹ́ cultural content and practice differ significantly from its reference and importance in Bààtonu. According to Palau Martí (Reference Palau Martí1992):

Dans le système de parenté bariba, la relation entre neveu et oncle maternel est valorisée, et le neveu peut s'approprier des biens de son oncle.

In the Bariba kinship system, the relationship between nephew and maternal uncle is valued, and the nephew can appropriate his uncle's property.Footnote 16

This suggests that, while ìyakọ and gonẹ̀ṣì refer to homologous sociological phenomena – that is, to banter between cross-cousins or in-laws – that are common to Ṣàbẹ́ and other Yorùbá subgroups, participants in gonẹ̀ṣí may be restricted among the Bààtonu as defined above.

In any event, it is not insignificant that gonẹ̀ṣì or ìyakọ, complete with cognate predicates such as jẹ́, which, in Yorùbá, may invariably be glossed as ‘eat’, ‘enjoy’ or ‘take part in’, is a sociological custom that characterizes cultures and traditions across the Sahara–Sahelian sub-region of West Africa, as Table 3 indicates.Footnote 17

Table 3 Parenté à plaisanterie: in-laws’ verbal jousting in West Africa

Source: Table based on <https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parenté_à_plaisanterie>.

Indeed, its cross-cultural features in common and its humanizing function persuaded UNESCO to declare this West African ‘institution’ an ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’.Footnote 19

Our interest here, again, lies in how to account for this relationship between the Bààtonu and the Yorùbá peoples. What was the intensity of the relationship and contact that resulted in the kind of transfer of form, meaning and usage that can be observed, when a perfectly transparent terminology exists in the borrowing language to express what Ṣàbẹ́ shared with other Yorùbá group members rather than with Bààtonu, the donor language and culture? It is perhaps not farfetched to attribute such a pattern of borrowing to an association that cannot be recent (post-fourteenth century). More importantly, neither ìyakọ nor gonẹ̀ṣì has a known reflection or cognate in any identifiable Middle Eastern tradition.

Dog names

The dog is a special member of the Yorùbá family, and not just in the way that a pet would be, like a tortoise or a parrot. By virtue of its special place in the Yorùbá family, the dog is not normally regarded as a source of meat, although a divinity such as Ògún (òrìṣà of all creative expressions) may, on special occasions, demand a dog as a sacrifice. Similarly, some momentous occasions even demanded human sacrifices in the Yorùbá past. Although dog names among the Yorùbá do not reflect the circumstances of the birth of the animal, as names of people do, they too encode the messages, admonitions, advice, aspirations and desires of their human owners and/or their families. Dog names often take the form of axiomatic gnomic expressions, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Yorùbá dog names

In addition, there are purely descriptive names that relate to the colour of the dog's coat: afún (one that is white/blond) and adú (one that is black).

The dog serves many purposes in the Yorùbá homestead. It is a faithful companion, a hunting partner, counsellor, baby's playmate and guard, and a cleaner in various circumstances. As the Yorùbá òwe goes: A kì í mọ orúkọ alájá, ká pa á jẹ (One does not know the name of the owner of a dog and still kill it for meat). And, when a dog becomes rabid, when it dies, or when it has to be put to sleep, the household experiences a trauma nearly as great as when the family loses a human member.

If a systematic inquiry into dog names and the culture of human–animal relations beyond mere ecological coexistence among the Yorùbá and the Bààtonu reveals a commonality that is also particular to the two groups or to the sub-region to which both belong, we would again like to use its conclusions to interrogate hypotheses about the external history of both peoples. I surmise that such an interrogation would be unlikely to corroborate the hypothesis of a Middle Eastern origin that is anywhere near as recent as existing historical conjectures propose.

Dog names among the BààtonuFootnote 20

Wendy Schottman (Reference Schottman1993) provides a fascinating study of Bààtonu dog names and naming. Her studyFootnote 21 strengthens our case for deep and sustained historical relatedness among the Bààtonu and the Yorùbá cultures and peoples and renders implausible the argument for a ‘Kisra legend [of] a migration story shared by a number of political and ethnic groups in modern Nigeria, Benin, and Cameroon, primarily the Borgu kingdom and the people of the Benue River valley’ as recently as the seventh century AD.Footnote 22

As with the Yorùbá people, the dog is an integral agent of tradition among the Bààtonu, an intimate existential partner, and not just a mere member of domestic livestock. The term ‘sekuru’ in the Bààtonu language (Schottman Reference Schottman1993) has the double meaning of ‘shame’ or ‘embarrassment’ and ‘modesty’, ‘respectfulness’, ‘deference’ or even ‘timidity’. In the Yorùbá language, the nominalized predicate ‘ìtìjú’ (‘ì=tì-ojú’, from the nominalizer prefix ì + predicate tì [‘push down’] + ojú [‘eye’]) has exactly the same double meaning.

From Schottman (Reference Schottman1993), modesty and the care taken not to offend anyone and/or cause embarrassment to other people, no matter their status in relation to the speaker, make the culture invest in dogs as a language surrogate by using gnomic expressions when a dog's name is not based on its coat colour or on any other physical trait. Thus, calling one's dog by name delivers the message inherent in its name to all hearers, including the one for whom the speaker intends the message.Footnote 23 Schottman puts it this way:

This diplomatic way of expressing oneself when a difference arises is doubly indirect: (a) The dog's owner makes use of a pseudo-addressee (the dog), and (b) the message is formulated with a proverb, therefore with words of which the owner is not the author. (Schottman Reference Schottman1993: 539)

Schottman explains further:

The use of a proverbial dog's name to communicate with a neighbor is a strategy which, although doubly indirect, remains rather transparent. Its transparency results primarily from the high degree of conventionalism of this use of proverbs. The overt communicative act, that of calling one's dog by the animal's name, is perfectly credible; hence this strategy offers little protection to the speaker. (Schottman Reference Schottman1993: 545)

Table 5 provides gnomic expressions that recall the Yorùbá instances of dog names in Table 4.Footnote 24

Table 5 Bààtonu dog names

The point should be made that we have called ‘gnomic expressions’ what Schottman refers to as ‘proverbs’, largely because a proverb does not normally subscribe to the ‘truth’ test, whereas gnomic expressions empirically do so within the culture that generates them. In this sense, dog names in both Table 4 and Table 5 are empirically valid in Yorùbá and Bààtonu respectively. And this transcultural validity is not accidental; rather, it speaks to the deep historical relatedness of the two cultures, which would hardly be the case in an argument based on the Kisra legend of migration, or on any other legend.

The story the horse tells

From the story of the horse, we can interpret both the collective (contact) and separate external and internal histories of the Bààtonu and Yorùbá peoples; this is at least as intriguing as what can be deduced from the points made above, and it certainly may point to the consequences of the inquiry suggested above. The fundamental question is the following: when did each or both of the peoples know about horses? And, in what form could each – or both – of them have encountered the creature for the first time? As Yorùbá scholars, our point of departure ought to have been to ask Ọ̀rúnmìlà, if we were not still roaming the wilderness in intellectual and physical exile:

In the absence of Ifá’s counsel, we must turn to the lore of both peoples as codified in macro-linguistic units such as òwe (commonly glossed as ‘proverbs’), riddles, idoms and oríkì, and to usages that contextualize these units in the life of the people. What follows is an invitation to a systematic inquiry that should either yield fresh plausible explanations for issues relating to our common history or confirm existing ones. The Yorùbá data presented below represent the tip of the iceberg, if for no other reason than that we have not been able to conduct the necessary fieldwork, not even for Yorùbá alone. I therefore do no more than raise questions to which later inquiry may offer answers.

First, I must pay tribute to that erudite and disciplined work The Horse in West African History (Law Reference Law1980). The work challenges us to gather systematic data so that we may put many issues beyond the realm of mere speculation. There is hardly any aspect of the history of the horse that its author, Robin Law, leaves untouched. I shall start with what appears to be Law's conclusion. He writes, on the basis of a careful consideration of the evidence:

More generally, the great diversity of West African equine vocabulary with its large number of apparently unrelated roots, tends to suggest that the spread of the horses within West Africa took place in relatively remote times.

What can be said with certainty is that horses were already established in West Africa at the time when contemporary Arabic sources from North Africa, Spain, and Sicily begin to tell us something about conditions there, from the ninth or tenth century A.C. onwards. (Law Reference Law1980)

Law finds that the Borgu term for horse, duma, is cognate only to the Gurma term ontamu. This would appear to suggest that Borgu does not share a micro-linguistic codification for the horse (as in Table 6) and the animal's tradition with Mande or with the Kwa-speaking peoples whose territories are found on the Atlantic Ocean coast in West Africa.

Table 6 Comparative terms for ‘equine' in West African languages

The list in Table 6 suggests that some equine mammals were common to these West African groups at some point in time. Whether or not Borgu experienced these differences in lexical codification should be clear from a study of larger linguistic units such as the Yorùbá ones in Table 6. I have no doubt that data from a more systematic inquiry will make us marvel at how a contact purportedly limited to less than eight centuries and based solely on the military use of the horse could have penetrated as deeply into the sinews of Yorùbá customs and their world view as these expressions, usages and institutional contexts indicate. If Bààtonu had comparable experiences with the horse, as similar materials may suggest, then what would the inferred time frame allow us to conclude about the history of the people and their contact with the Yorùbá?

The horse in Yorùbá art

The pre-eminence of representations of the horse in modern Yorùbá visual art defies explanation, if we assume that contact with the horse occurred as late as the ninth century CE. The presupposition that the military use of the horse from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth century in intra-group wars impressed the figure of the animal so indelibly on the reality of the people leaves many questions unanswered. Why, for example, does the horse enjoy prominence in the wood carvings of Eastern Yorùbá, an area that the cavalries of the various invaders hardly reached? The artistic representation of the horse features in the palace of the Ọba of Benin for ceremonial purposes, in a setting where horsemanship appeared to call for extra precautions to ensure the security of the ruler. Certainly, non-military visual representations of the horse require explanation in such a setting, in the absence of putative belated sixteenth- to nineteenth-century contact with the animal.

Equally intriguing is the appearance of representations in Ifá objects, along with linguistic expressions codifying the significance of such appearances. For instance, the divinatory tray, ọpọ́n Ifá, has four major quadrants. The lower left quadrant is afùrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ṣayọ̀, ‘one who engenders happiness using the fly whisk’ – assuming, that is, that ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ refers to a ‘fly whisk’ made of a horse's tail. It is, of course, conceivable that the identification of ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ with Ifá is a later transfer of a reference to the tail of some other animal, with the function similarly transferred to that of the horse. The term ìrù glosses as ‘tail’ without reference to any specific animal. Furthermore, Yorùbá Ọba – who, according to tradition, may wear the beaded crown – carry ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ imbued with their àṣẹ, their ‘mythic power’ or ‘life force’, whenever they are in a position to exercise or dispense that power, such as when seated in state, on ritual occasions, or on formal outings to acknowledge their subjects and bless them. Their ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ is, however, made from rọ̀rọ̀ àgbò, ‘the mane of a white ram’, and never from the tail of a horse or of any other animal. We know, of course, that the ram, àgbò, and not the horse, occupies an important place in the Yorùbá myth of origin. The ram, or possibly some mythical person metonymically named ̛àgbò, is Ifá’s mythical customs officer. It would therefore appear conceivable that the predicate fùrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ṣayọ̀ connotes the diviner's àṣẹ, which he may deploy with a gesture with ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ to command, with efficacy, a material base or socio-psychological ambiance for joy for both the diviner and the supplicant.

One cannot so easily dismiss the representation of the horse on Ifá art objects. For one thing, the lexical formative ìrù in ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ in animal anatomy refers strictly to the tail.Footnote 27 To the extent, therefore, that the Ọba's ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ is made of the mane of a white ram, that term may be argued to properly refer to Ọba's item of power; only analogically and, because of the force of its application in the hands of Ọba and babaláwo, did it come to refer to a horse's tail, for reasons of morphological similarity.Footnote 28 This argument suggests that the presence of the horse in the Yorùbá tradition pre-dates the tradition of Ọba, and, ipso facto, it also pre-dates the association of the beaded crown with the àṣẹ, which the Ọba dispenses with ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ (see Figure 1). Notice that the Ọba's ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ is invariably white, as opposed to the sombre colour of the horse's tail. This confirms that the Ọba's ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ (even that of Lọ́bùn, a woman Ọba) is made from the mane of rams.

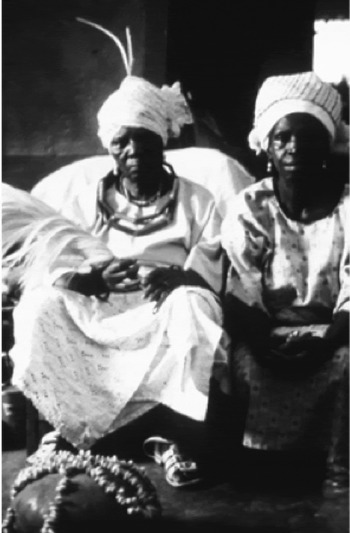

Figure 1a (a) Lọ́bùn (or Ọlọ́bùn) of Oǹdó (also called ‘Ọba obìnrin). Source: Abíọ́dún (Reference Abíọ́dún2014: 110).

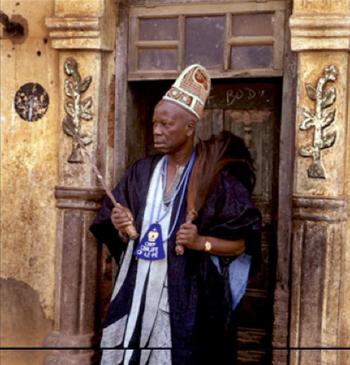

Figure 1b The Ọba of Baporo sits in state with adéńlá and beaded fly whisk during the Ògún Ogenegene festival, Ìjẹ̀bu-Yorùbá. Source: Drewal and Mason (Reference Drewal and Mason1998: 55).

Figure 1c Ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ ìlẹ̀kẹ̀ (paired beaded fly whisk). These would have been worn around the neck like the linked edan of Òṣùgbó elders. Source: Drewal and Mason (Reference Drewal and Mason1998: 223).

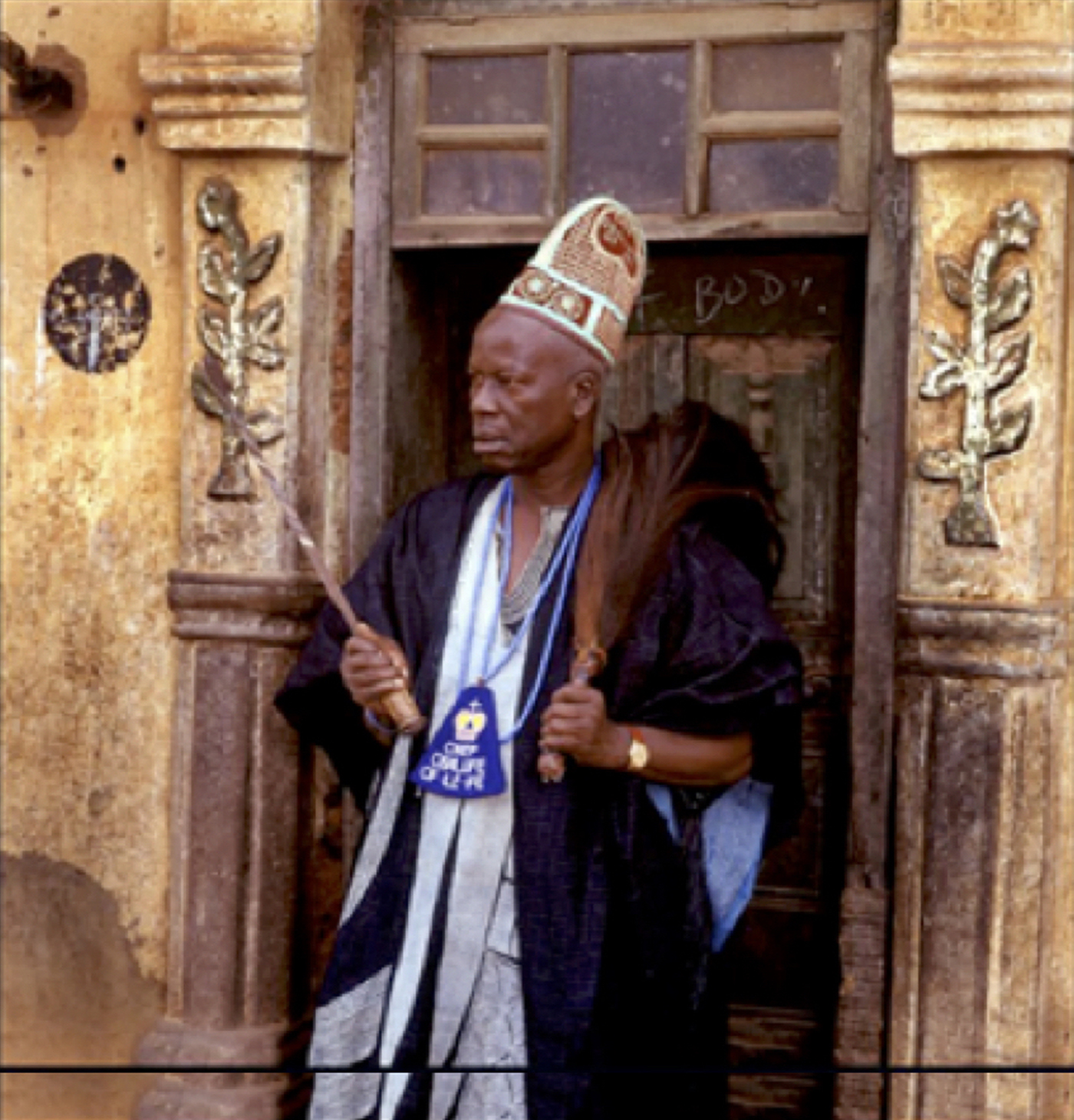

Figure 1d Chief S. L. Omiṣadé, the Ọbalúfẹ̀ (Ọ̀rúntọ́ or Ọọ̀ni Òde, prime minister equivalent of Ifẹ̀). Source: Abíọ́dún (Reference Abíọ́dún2014: 151).Footnote 35

After the Ọba, Ifá priests are the next most prominent group of people who use the ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ as a symbol of their priesthood and of their power to dispense àṣẹ like an Ọba, albeit only at divinatory and formal sessions. A verse from an àyájọ́ (incantation), cited by Abíọ́dún (Reference Abíọ́dún2014: 139)Footnote 29 in appreciating the Zollman àgéré, confirms this:

Bí babaláwo méjì bá pàdé

Wọn a ṣe ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ wọn yẹturuyẹturu

Whenever two Ifá priests meet,

They wave their horsetail fly whisk in salutation/They wave their ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ ‘full-fluff’ in acknowledgementFootnote 30

The exceptionally long ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ in this àgéré Ifá makes a strong visual statement and suggests its verbal corollary from ọfọ̀ (incantation), another authoritative Yorùbá source:

Ó dá ko kúnkúǹdúkú tíí ṣọlọ́jà iṣu

Òun ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ tíí ṣọmọ Olókun Ṣẹ̀níadé

Wọ́n ní bó bá yẹ̀ ‘rùkẹ̀rẹ̀ tán, tó dẹ̀ ‘rùkẹ̀rẹ̀ lọ́rùn,

Ò dẹni à-gbé-jó, ó dẹni à-gbà-yẹ̀wò.

À-gbè-jó làá gbé ‘rù ẹṣin

À-gbà-yẹ̀wò ni tì ‘rùkẹ̀rẹ̀ Footnote 31

It was divined for kúnkúǹdúkú [sweet potato] who is the king of yams,

And the horsetail who was the child of Olókun Ṣẹ̀níadé [Creator God]

It was predicted that by the time the horsetail had become famous and prosperous

He would become the focus of attention.

He danced carrying the horsetail.

We respect the horsetail in admirationFootnote 32

We recalibrate some lines of the ọfọ̀ as follows:

In divinatory settings, one says ‘Ẹ yẹ̀ mí wò’, ‘Please, interrogate my lot.’ Also consider àyèwò, which connotes a diagnostic process, or a process of systematic inquiry, when asserted before a physician, an Ifá cognoscente, or anyone equipped with the competence to make prescriptions, with an acknowledged measure of credibility, following a thorough diagnosis. If, as Abíọ́dún (Reference Abíọ́dún2014: 139) states, the ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ on Zollman àgéré Ifá is ‘exceptionally long’, then it must be from the tail of a horse, and is called ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ due to its morphological resemblance to the type carried by babaláwo and Ọba. The ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ from the horse's tail is most suitable for ritual performance purposes, but is unsuitable for babaláwo to acknowledge one another at solemn moments, or for dispensing and/or asserting the àṣẹ or ‘effective power’, which they alone may deploy during the process of divination. Furthermore, the yẹturuyẹturu motion of the babaláwo’s ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ is not a ritual motion; rather, it is a symbolic gesture, imbued with power, made by someone who is privy to the mystery of Ifá to another, from babaláwo to clients for àṣẹ. We must accept the powerful symbolism of àṣẹ in the hands of the Ọba and the babaláwo as ‘diminutive ìrù’, or ìrù tí ó kẹ̀rẹ̀ – literally, ‘a tail that is diminutive’. Its nimbleness makes it easy for those entitled to use it to handle it with dignity and grace.

The separate primordial ritual function of the horse's tail further underscores our conclusion that the horse must be present in the deep and remote history of Yorùbá tradition and culture, and is less likely to have arrived with more recent migration, or with the military adventurism of jihadists.Footnote 34

This is not all. Rowland Abiọdún (Reference Abíọ́dún and Abimbola1975) notes that the ‘sculpture and apparatus of Ifá range from natural unadorned objects such as ikin (sacred palm-kernel nuts) to the highly sophisticated and sculptured àgéré Ifá (a wooden vessel with lid) for housing ikin’. Whereas the horse does not feature among the animals represented on ọpọ́n Ifá, Abiọdún (ibid.: 449) describes àgéré Ifá as follows:

The figures in the sculpture of àgéré are ordinary men responding humanly and naturally to the success of their supplication. In the conventional way they drum, sing, and dance with horse-tail fly-whisk in hand, ride on horseback with or without a weapon (in the case of victory in war or success of a similar nature), and make ritual sacrifice to express their gratitude to Ọ̀rúnmìlà.

Other references suggest further that both the horse and the reading of ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ as the tail of the horse may be primordial in the Ifá tradition. Thus, babaláwo or ‘Ifá exponents’, commonly referred to as ‘diviners’, wish for and express ultimate success by riding a horse when practising their profession: ẹṣin ni n óò máa gùn ṣawo (the horse it is I will ride to dispense the mystery of essence and existence). Furthermore, in putting a value on Ifá objects, beaded ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ (1,200 cowries) ranks after only àgéré (at 3,200 cowries) and ìrọ́kẹ́, the usually ornately adorned ivory tapper used to invoke Ọ̀rúnmìlà at the start of a consultation.

In short, at worst one cannot conclude that the horse has not always been associated with Ọ̀rúnmìlà, the only divinity in the Yorùbá pantheon present at creation and the acknowledged custodian of the account, logós, of all objects of consciousness, including thoughts. If the horse enjoys that association, how remote could its appearance in the Yorùbá world be? We know that the Ewe-Fon of the Benin littoral have Fá, a system of geomancy that is accepted as cognate with the Yorùbá Ifá. Do Bààtonu have a similar system? If they do, is the horse as closely associated with Fá as it is with the Yorùbá Ifá? If the answer is as uncertain as is the case for Ifá, then we have good grounds to find corroborating evidence here too, in the lore of both peoples, in order to argue for a remote antiquity in their association – and this certainly renders nonsensical a Middle Eastern or an Asia Minor migration to West Africa.

The horse in Yorùbá discourse and material culture

Equine equipment

The bridle, spur and saddle are basic to horsemanship, including the military use of the horse. The three terms gloss as follows in Yorùbá: ìjánu (<ì-já-ẹnu, ‘that which is used to pick the mouth), kẹ́sẹ́ and gàárì.

Of the three terms, only ìjánu is morphemically analysable in Yorùbá; the remaining two are arguably loan words. Bridles were widely used in the region in the pre-Islamic period, when they served purposes other than military, and horsemanship was hardly a professional skill. Linguistic usages, such as those in Table 7, would appear to confirm the relative antiquity of the bridle.

Table 7 Phrases relating to horses and their equipment

The Yorùbá world view and epistemology that undergird traditional names and naming inform the òwe in Table 7, while the very concept of ọmọlúwàbí (Awoniyi Reference Awoniyi and Abimbola1975; Abimbola Reference Abimbola1975) gives force to the ìjánu metaphor. In both òwe and metaphors, the remaining two entries have more mundane semantically simplex connotations. Ìjánu expressions point to a pristine contact with the vehicle they refer to: namely, the horse. Their origin, too, may lie in the lap of Ifá. Not so the other two sets: kẹ́sẹ́ and gàárì.

The horse and rider predicate in personal names and naming

I have invoked the primordial nature of names and naming among the Yorùbá and the Bààtonu. Consider, now, in Table 8, names that incorporate the horse and rider predicates, particularly in the Yorùbá culture.

Table 8 Names that incorporate the horse and rider predicates

Apart from names of children born with peculiar presentations through the uterine passage – for example, ìgè, ‘foot-first orientation’ – or with unusual physical features such as extra digits (olúgbódi) or with locks of hair (dàda), most Yorùbá names are either whole clauses or, as a minimum, simplex predicates. Names in column three involve simple, uni-lexical predicates – dà, ‘to develop into or become’, and tó, ‘become equal to’ – while the complement or object in each case is òyìnbó, ‘white person’. Names in columns one and two, on the other hand, feature complex predicates, usually referred to as a serial verb construction (the verbs underlined); this is perhaps the distinctive syntactic feature of the languages of the sub-region of Borgu and Yorùbá. Furthermore, whereas the names in column three challenge the pride of the stranger, those in one and two memorialize the cultural landscape or express the hopes and aspirations of the family at the arrival of the child. The occurrences of horse, ẹṣin, in column one participate in the latter. These instances of ẹṣin in naming suggest an antiquity that points to anteriority to the Bààtonu and Yorùbá encounter with white people, which occurred at the earliest in the fifteenth century CE.

The horse in òwe (proverbs)

The pervasiveness of occurrences of the horse in òwe, commonly inadequately glossed as ‘proverbs’, most cogently raises the issue of the antiquity of the contact of the Yorùbá with the animal, and/or the intensity and extent of the impact of that contact, but pays scant regard to the duration of that experience. The argument dating the horse–Yorùbá contact to the Islamic period puts a great deal of weight on the presumed intense trauma and/or triumph of military escapades and adventures. When we turn to perhaps the most enduring codification of the people's historical experience distilled into communicable minuscule details with the force of each Odù Ifá, we find ourselves called upon to exercise the utmost intellectual responsibility before reaching any conclusion.

Consider that the Yorùbá pack the force, rationale, delivery, context and reception of the horse òwe in the following text:

At this stage of our inquiry, it is unrealistic to pretend to be able to make any definitive statement about the scope of the horse òwe in Yorùbá, as there exists at least one horse òwe for every facet of Yorùbá reality or thought. We will content ourselves with this one robust example to support our supposition about the antiquity of the horse among the people.

Conventional wisdom does not dispute the antiquity of the genetic relationship between the Yorùbá and the Igbo peoples. Yet, where the Yorùbá say ‘òwe lẹṣin ọ̀rọ̀’, the Igbo say ‘the proverb is the palm oil with which the yam is eaten’ (Achebe Reference Achebe1958). Is it the indigenous status of the oil palm and its multifarious life-sustaining uses that lend force to the Igbo proverb, or the recent export value, enhanced by the perceived superiority of the colonial exploiters? Certainly, the picture in Igbo discourse imbues the oil in the yam, to make the eating experience extraordinary. To extrapolate from the Igbo discourse, whereas the babaláwo aspires to ride a horse to material success and recognition – note, not to efficacy in divining – in the horse òwe, the discourse and not the speaker is in the saddle. This makes plausible the recoverability of the reference, when, due to human foible, the discourse which òwe innervates with force miscarries.

In order to underscore the fundamental nature of the presence and force of the horse in Yorùbá òwe, I examined Owomoyela (Reference Owomoyela1988). Out of 875 entries of substantives that serve as a vehicle for instances of òwe, I identified fourteen occurrences of the term ẹṣin (horse), and the same number for aṣọ (cloth), adìẹ (chicken) and odò (river or stream) (see Table 9). This suggests that ẹṣin, too, ought to be counted among the items of primordial significance to the people and its culture.

Table 9 The presence of the horse in Yorùbá òwe

Out of the fourteen occurrences of òwe ẹṣin or ‘horse proverbs’, only four pertain to power, wealth and/or material well-being; the remaining concern interpersonal relationships. One may therefore suggest that the force of the horse òwe has more to do with the graphic nature of its presence in human relational experience than with power relations and wealth. Even where power and authority are concerned, the horse òwe empowers both the source of the information and the people as the ultimate fountainhead of authority, as the phrases below suggest:

ẹṣin pòpórò kì í mọ̀nà ju ẹni tó gùn ún lọ

a straw horse does not know the road better than its rider

ẹni tó gbéni gẹṣin lóní ká sọ̣̀pàkọ́ lùké

the person who puts one on the mount gives one the authority to act the role

The horse in other spheres of Yorùbá life

In the apparatus of the state

It is not surprising that ẹṣin has an integral place in the apparatus of the state among the Yorùbá. Its stature in the Yorùbá power structure and tradition has ironically been projected throughout the world over the past thirty years by a work of art: the play Ikú Olókùn Ẹṣin (Iṣọlá Reference Ìṣọ̀lá1994),Footnote 37 which most people believed earned Wọlé Ṣoyinka the 1986 Nobel Prize for Literature at the impressive age of fifty-two. Perhaps the cardinal point that one should make is that the decision of one Olókùn Ẹṣin, the ‘King's Horseman’, not to accompany his king in death, as tradition commands, signals a radical subversion of the system of values that has sustained the Yorùbá culture of governance since the effective organization of the city state in its Ọ̀yọ́ manifestation among the Yorùbá. Members of the household of the Ọba who enjoy the exercise of unchallenged power and authority cannot live within the city walls while the Ọba is alive and/or must die with the Ọba upon his demise. This applies to the àrẹmọ, the first-born son, of the reigning Ọba, and to Ààrẹ ọ̀nà Kaka-ǹ-fò, the Field Marshall of the Imperial Ọ̀yọ́. Olókùn Ẹṣin enjoyed unusual benefits of power distinct from ascribed authority.

Again, the relative antiquity of the institution of Ọba in its Ọ̀yọ́ form, and of the office of the Olókùn Ẹṣin in particular, interests us here. This is also why I would agree with Robin Law (Reference Law1980) about the historical importance of the festival of so-sin, ‘horse-tying’, among the Ewe-Fon of the Benin–Togo littoral. The ritual chieftain, sogan, is in charge of the attendant rites. Does the existence and codification of both so-sin and sogan among the Ewe-Fon have anything to do with the antiquity of the geomancy system Fá, which undoubtedly signals the antiquity of the Yorùbá–Ewe-Fon contact? Does there exist a homologous institutional system among the Bààtonu, which would argue, as ẹṣin appears to do, for the remoteness of the appearance and impact of the animal in the Yorùbá world and/or in association with the two peoples? The existence of discourse forms such as òwe that reference the apparatus of the state need not detain us further here.

The horse and the divinities

Since the Ọba is alayé, aláṣẹ èkejì òrìṣà, ‘the terrestrial custodian of àṣẹ (the life force) and authority, second only to the Prime Mover divinity’, it is not surprising that ẹṣin figures prominently both in the symbols of hierarchy in the comity of the òrìṣà in the Yorùbá world view and social organization, and in the discourse that codifies this presence. Thus, the medium or devotee of an òrìṣà, in ritual situations and in live ritual processes when the medium is possessed, is referred to as ẹlẹ́gùn òrìṣà, ‘one whom the òrìṣà rides’, or as ẹṣin òrìṣà, ‘the horse of òrìṣà’.Footnote 38

This is, of course, possible; but is it plausible to suggest that both the discourse and its terms of reference are adventitious developments, which date from the relatively recent contact with Islam, post-seventh century CE? The fundamental henotheistic conception and configuration of the Yorùbá pantheon is not identifiable with or traceable to any Middle Eastern or Semitic antecedent – pace Bọ́lájí Ìdòwú. This, then, argues against the suggestion or insinuation that the trope ẹ̀gùn òòṣà owes the physical presence and power that the devotees perceive and experience when the medium is possessed to a Middle Eastern tradition whose godhead is both remote and impermissibly awe-inspiring. If anything, the force of the dictum òwe lẹṣin ọ̀rọ̀ derives, to all intents and purposes, from the indigenous antecedents ẹ̀gùn òrìṣà and ẹlẹ́gùn òrìṣà.

At this point, it is best to leave a logical pursuit of this argument to poetic imagination, which favours assigning a remote antiquity beyond any Middle Eastern contact to the Yorùbá consciousness and epistemology.

Oríkì

As Oyèláràn and Adéwọlé (Reference Achebe2007) insist, properly speaking, oríkì does not refer to the praise or adulation of anyone or anything. In fact, among the Yorùbá verbal arts, the genre in essence unequivocally but graphically presents whatever idiosyncratic observations, qualities or attributes single out its subject. Oríkì has a primordial status among Yorùbá verbal arts. It is, therefore, important that the horse again features literally and figuratively not only in citations of the mighty and the lowly among human beings in society, but also in citations of all remarkable objects of human experience, including elements of thoughts. Consider the following facetious citation of palm wine, that readily accessible indigenous lubricating oil of social gatherings among the Yorùbá – and probably throughout West Africa:

The horse in Yorùbá final rites

If the horse is so integral to Yorùbá life on earth – which, after all, is àjò, ‘a journey’, and thus makes all humans pilgrims – what is its place in Yorùbá thinking about death and dying? To answer this, we must turn again both to the Yorùbá discourse about death and dying, and to objects that hold a special place in the rites of passage particular to both. The two texts below invite us to pry a little deeper for a definitive answer:

Amidst the pathos and solemnity of the funeralia at the death of dignitaries, mourners and survivors carry full-length horse-tail fly whisks to enhance their ceremonial movements and gestures – the darker the more desirable. In addition to their efficacy in whisking flies off the dead body lying in state, funeral ìrùkẹ̀rẹ̀ symbolize what the departed has left to hold on to. The movement of and with the horse-tail whisk are accompanied with dirges, mainly oríkì of the departed, funereal dances and performances. Other dances linked to solemn Yorùbá occasions use both the horse-tail whisks and whisks made from the tails of other animals. An example of the latter accompanies the vigorous àgbọn performance in Ilé-Ifẹ̀.

Horse riddles

It is perhaps fitting to conclude this look at the phenomenon of the horse as plausible signifier of the autochthonous status of the Yorùbá in their West African homeland, and, on the basis of historical association, of the Bààtonu, with a section on riddles – àlọ́ àpamọ̀ in Yorùbá. And, given the function of the riddle in the epistemological consciousness of a people, we should not be surprised that horse riddles, like horse òwe and horse metaphors, abound in Yorùbá and also in Bààtonu. Riddles such as the two below – one that alludes to a horse and one that refers directly to a horse – occur rather commonly. For an appreciation of the non-trivial structure, meaning and function of àlọ́ àpamọ̀, Yai (Reference Yai and Oyèláràn1978) is particularly useful.Footnote 39

If the reader divines the clue to the àlọ́ àpamọ̀ in the second example, without a peek at the footnote, we will have embraced the challenge and the discipline required to uncover why Borgu is, in the final analysis, the orı́ta of the cultures in the sub-region of encounter between the Yorùbá and the Bààtonu, and why Borgu has played that role since times remote enough to make any myth of a Middle Eastern provenance implausible for any of the peoples who have always inhabited our space, our place on this planet – even if the myth of a Middle Eastern or Semitic provenance did not run counter to what recent inquiries into the human genome suggest as the direction of out-migration of the human species from its African locus of emergence.